I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Norway and sectoral balances

Some readers have written in and asked about whether Norway behaves like a modern monetary economy after they read the New York Times article titled Thriving Norway Provides an Economics Lesson. The short answer is yes but this is a case that raises interesting issues about the way the government and non-government sectors interact and how sustained economic growth and high employment can be accompanied by a budget surplus. Yes, it is possible but atypical. In this blog I provide the explanation. We also encounter some very dodgy manipulation of data to push an ideological line! Not good.

According to the article people are surprised that “Norway’s economy grew 3 percent last year as many nations plunged into a recession.” The Norwegian finance minister (Kristin Halvorsen) who is allegedly not a supporter of free markets recently authorised Norway’s sovereign fund (one of the biggest in the World) to accumulate finanical assets at the same time as financial markets were in a state of panic. Norway has also bucked the trend towards neo-liberals which has “sought to limit the role of government”. Instead “Norway strengthened its cradle-to-grave welfare state.” The other point that the article notes is that in addition to relatively robust growth in 2008 (“just under 3 percent”):

The government enjoys a budget surplus of 11 percent and its ledger is entirely free of debt.

The article is actually trying to compare this debt-free budget surplus state with the US which has a large budget deficit (over 13 per cent of GDP and rising) and growing debt (“total debt to $11 trillion, or 65 percent of the size of its economy”). The intent is to demonise the deficits and debt build-up and, instead, demonstrate the virtue of budget surpluses.

Quoting facts is fine but the interpretation of them has to be done in an understanding way in order to draw the correct conclusions.

Further, immediately, I see statistics being quoted I get curious. I was sure that Norway did not grow at 3 per cent last year.

So to ease my worried mind, I went to the place you go for Norwegian data – Statistics Norway’s StatBank – which is the official national statistics agency (like the ABS!).

First, I checked the GDP growth performance. Statistics Norway data also does not accord with the journalist’s claims about the growth rate. Their official data shows that in 2007 the Norwegian economy grew in real terms by 3.2 per cent. In 2008, this growth rate dropped to 2 per cent in 2008. It doesn’t alter the nature of the argument being presented in the article substantially but it always pays to use the correct data and not inflate your claims. When I find a journalist is stretching the truth I get suspicious.

And my suspicions deepened when I read on. You start to understand the ideological slant of the article when you read the following summary of Norway’s situation:

… Even though prices have sharply declined, the government is not particularly worried. That is because Norway avoided the usual trap that plagues many energy-rich countries. Instead of spending its riches lavishly, it passed legislation ensuring that oil revenue went straight into its sovereign wealth fund, state money that is used to make investments around the world … Norway’s relative frugality stands in stark contrast to Britain, which spent most of its North Sea oil revenue – and more – during the boom years. Government spending rose to 47 percent of G.D.P., from 42 percent in 2003. By comparison, public spending in Norway fell to 40 percent from 48 percent of G.D.P.

Once again, I was worried. I know that private consumption in Norway is lower than other countries (such as Australia). But I also know that its public sector is nowhere near 42-45 per cent of the total economy.

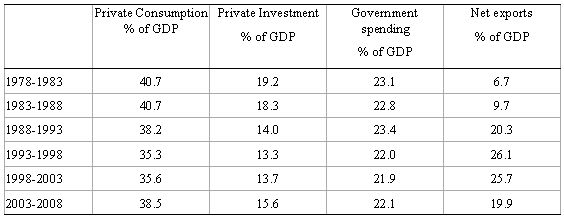

So I did some more checking and produced the following table which is constructed from the official data available from Statistics Norway – 06128: Final expenditure and gross domestic product. Seasonally adjusted figures.

I computed the components of GDP (ignoring small movements in inventories and the statistical discrepancy). You can see that: (a) government spending is nowhere near 42 per cent and in the last five years it has fallen as a proportion of GDP. Further, public spending has remained a relatively stable proportion of total demand in Norway.

The journalist also selectively quotes some Norwegian who is an exemplar for neo-liberal individualism. I am seeking a reaction to this from my Norwegian friends and will update the blog when I get it. It is certainly not my impression that this “independent – buy everything with cash” is at all representative.

The rest of the article is about the net export boom derived from its substantial oil reserves. Norway is a small open economy and is one of the World’s largest oil exporters. They have been flooded with export revenue as energy prices soared over the last few years. Their case is special because it highlights a situation where an economy can grow even though the public sector is running surpluses without increasing indebtedness in the private domestic sector.

In macroeconomics we have a way of looking at the national accounts (the expenditure and income data) which allows us to highlight the various sectors – the government sector and the non-government sector. So we start by focusing on the final expenditure components of consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G) , and net exports (exports minus imports) (NX). The basic aggregate demand equation is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

In terms of the uses that national income (GDP) can be put too, we say:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume, save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

So if we equate these two ideas about the same thing (GDP) we get:

C + S + T = C + I + G + (X – M)

Which we then can simplify by cancelling out the C from both sides and re-arranging (shifting things around but still satisfying the rules of algebra) into what we call the sectoral balances view of the national accounts. There are three sectoral balances derived – the Budget Deficit (G – T), the Current Account balance (X – M) and the private domestic balance (S – I). These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but we just keep them in $ values here:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

You can then manipulate these balances to tell stories about what is going on in a country.

For example, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and a public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. So if X = 10 and M = 20, X - M = -10 (a current account deficit). Also if G = 20 and T = 30, G - T = -10 (a budget surplus). So the right-hand side of the sectoral balances equation will equal (20 - 30) + (10 - 20) = -20. As a matter of accounting then (S - I) = -20 which means that the domestic private sector is spending more than they are earning because I > S by 20 (whatever $ units we like). So the fiscal drag from the public sector is coinciding with an influx of net savings from the external sector. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. It is an unsustainable growth path.

This situation describes the recent history of Australia.

So if we usually have a current account deficit (X – M < 0) then for the private domestic sector to net save (S - I) > 0, then the public budget deficit has to be large enough to offset the current account deficit. Say, (X – M) = -20 (as above). Then a balanced budget (G – T = 0) will force the domestic private sector to spend more than they are earning (S – I) = -20. But a government deficit of 25 (for example, G = 55 and T = 30) will give a right-hand solution of (55 – 30) + (10 – 20) = 15. The domestic private sector can net save.

But what about Norway? It is currently running huge net export surpluses (as shown in the table above) and private domestic surpluses (S – I). The data from Statistics Norway shows that in 2003 the private saving ratio was 9.2 per cent of GDP and this peaked at 10.1 per cent in 2005 and has since declined to 2.0.

Using the sectoral balance framework, we can say that a current account surplus (X – M > 0) allows the government to run a budget surplus (G – T < 0) and still allow the private domestic sector to net save (S - I) > 0. In fact, the budget surplus is ensuring that the total net spending injection to the economy matches the spending gap derived from the desire to save. If the government tried to run deficits in this case, then spending overall would be too large relative to the real capacity of the economy and inflation would result.

So, as a matter of accounting between the sectors, a government budget deficit adds net financial assets (adding to non government savings) available to the private sector and a budget surplus has the opposite effect. The last point requires further explanation as it is crucial to understanding the basis of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

In aggregate, there can be no net savings of financial assets of the non-government sector without cumulative government deficit spending. In a closed economy, NX = 0 and government deficits translate dollar-for-dollar into private domestic surpluses (savings). In an open economy, if we disaggregate the non-government sector into the private and foreign sectors, then total private savings is equal to private investment, the government budget deficit, and net exports, as net exports represent the net financial asset savings of non-residents.

It remains true, however, that the only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings) and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save (financial assets) and thus eliminate unemployment is the currency monopolist – the government. It does this by net spending (G > T).

Additionally, and contrary to mainstream rhetoric, yet ironically, necessarily consistent with national income accounting, the systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses (G < T) is dollar-for-dollar manifested as declines in non-government savings. If the aim was to boost the savings of the private domestic sector, when net exports are in deficit, then taxes in aggregate would have to be less than total government spending. That is, a budget deficit (G > T) would be required.

Conclusion: Norway is in an atypical situation – being swamped with net export spending injections.

The journalist also quotes some investment banker after noting that Norwegians enjoy a high standard of living with lower working hours than most. He is quoted as saying:

This is an oil-for-leisure program … We have become complacent … More and more vacation houses are being built. We have more holidays than most countries and extremely generous benefits and sick leave policies. Some day the dream will end.

Well, then the sectoral balances will move in a different direction. Then if the political will remains for Norwegians to enjoy a solidaristic existence then budget deficits will take up the slack left by the declining net exports and all will remain well in the land of fjords.

Good piece, Bill.

Two questions . . . your data for govt as a % of GDP . . . does that include transfers? Could that perhaps be the discrepancy b/n your data and the article?

Also, anything in the article on whether the rise (then fall) in oil prices drove Norway’s performance (just as it drives that of other oil exporters), rather than its “frugality” or (to say it differently) its adherence to the neo-liberal model?

At any rate, when you understand the sectoral balances, one can see that Norway’s performance MUST be atypical, since it is by definition impossible for all nations to run trade surpluses, particularly of Norway’s magnitude.

Finally, I must object (as I always do) to data cited in the NYT article regarding the US national debt. The correct figures are NOT $11 trillion and 65% of GDP. Those figures include the so-called trust funds. Even the neo-liberal model in graduate texts explains that the correct measure incorporates only those parts of the national debt for which there are interest payments to the non-government sector. Those parts come to a bit over 40% of GDP at present, in fact (and until last year these were about 35-36% of GDP).

Best,

Scott

Dear Scott

Good point about the transfers. The following data (latest available) is 2007 doesn’t suggest that explains the 20 per cent gap. Transfers are significant but so are taxes.

2007 National Income account (NOK million) – http://www.ssb.no/ifhus_en/tab-2009-03-05-01-en.html

Income from work 885,333.5

Transfers 258,694.1

Taxable transfers 222,187.7

Tax-free transfers 36,506.4

Total income 1,222,444.9

Total assessed taxes and negative transfers 309547.8

Total after tax income 912,897.1

2007 Expenditure account – http://www.ssb.no/nr_en/tabe-01.html

C 941,592 NOK million 41.4% total GDP

I 454,923 NOK million 20.0% total GDP

G 517,367 NOK million 22.7% total GDP

X 1,042,254 NOK million 45.8% total GDP

M 679,026 NOK million 29.8% total GDP

GDP 2,277,111 NOK million

Your point about the US data confirms the slippery nature of the article.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

I don’t know if you are still monitoring this page, but I tripped across it this morning, and the mismatch in government expenditure figures caught my eye. It is wonderful to see a discussion like this, where journalists are taken to task, and there is some attempt to replicate findings.

I believe the NY Times reporter was using the SSB’s “General Government Expenditures” data from their tables on “General government. Revenue and expenditure. Accrued values. NOK million.” This table lists general (not central, not local, but general) government income and expenditure data for every year. In 2007, the total general government expenditures was given to be 899,517 million NOK, and the general government’s “Net acquisitions of non-financial assets” was 27,972 million NOK. By the SSB’s own calculations, then “total (general government) expenditures” was 927,489 million NOK. That corresponds to roughly 40% of GDP that year.

The total government expense figure includes figures for things like: Compensation of employees; Use of good and services; Consumption of fixed capital; Social benefits in kind; Property expense; Social benefits in cash; Pensions; Retirement pensions; Disability pensions; Other pensions; Family allowances; Child benefits; Cash benefit scheme; Sickness and parental benefits; Subsidies; current transfers….)

Above, you reference 517,637 million NOK as the government’s expenditures in 2007. Unfortunately, it is not possible to follow the links (SSB’s Statbank system is terrible that way) and find the exact table from which you drew these figures, so I’m not sure exactly what this figure captures. You mention that you are drawing from the National Accounts data (Final expenditure and gross domestic product. Current prices. NOK million), and when I look at the 2007 data column, the closest figure I find to 517,637 million is for “Final demand from general government” (515,960). Is that what you are using to capture your “G” variable in the discussion above?

I can mail you pdfs of the relevant tables, if you want. But I wonder if you could discuss the appropriateness of these different indicators for government expenditures (as they vary widely). After all, when you search for “government expenditures” on the SSB site, you are going to end up on the page used by the NYT journalist.

Sincerely, Jonathon