I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

Barnaby, better to walk before we run

Today I have been thinking about the macroeconomics textbook that Randy Wray and I are writing at present. We hope to complete it in the coming year. I also get many E-mails from readers expressing confusion with some of the basic national income concepts that underpin modern monetary theory (MMT). In recent days in the comments area, we have seen elaborate examples from utopia/dystopia which while interesting fail the basic national income tests of stock-flow consistency. Most of the logic used by deficit terrorists to underscore their demands for fiscal austerity are also based on a failure to understand these fundamental principles. So once again I provide a simple model to help us organise our thoughts and to delve into the elemental concepts. It is clear that in order to come to terms with more complicated aspects of MMT, one has to “walk before they can run”. So its back home today.

Today, was a classic case. The Opposition Finance spokesperson Barnaby Joyce (or B Jo as he is being called – for what reason?) who is fast becoming the “joke of the town” told ABC news that Australia was in danger of defaulting on its sovereign debt. He was quoted as saying:

You’ve got to ask the question: how far into debt do you want to go? We are getting to a point where we can’t repay it. Let’s look at exactly what they’re doing now and ask this very simple question: are you paying back your money, are you even meeting your interest component, and can you keep the debt stable? Or is the debt racing ahead by more than even the interest expense? And if it is, any household budget will tell you that’s a very dangerous place to be.

So Mr. Joyce hasn’t the first clue about how the monetary system operates nor the difference between the household budget and the Australian government budget. I thought this little tutorial would help.

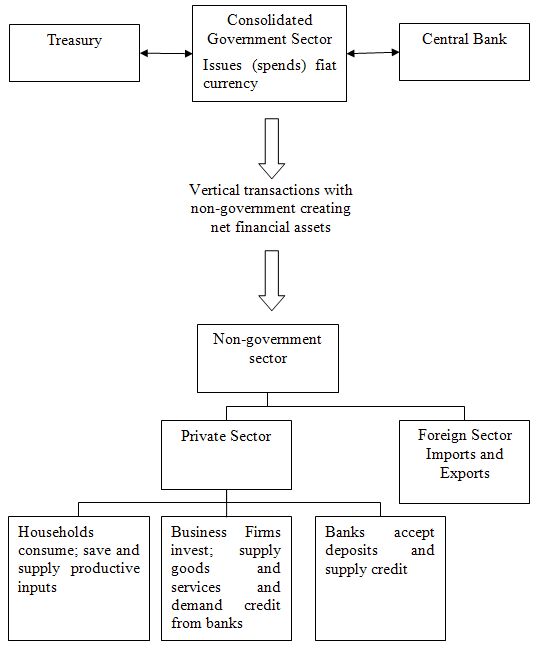

To help Barnaby along we need to simplify things. I would refer him to this diagram, which should be in the first chapter of every macroeconomics textbook. It depicts the essential structural relations between the government and non-government sectors. You can make it bigger by clicking on it and it might help to print it for reference (to avoid scrolling up and down).

You can see that the diagram is arranged in a vertical manner with the government sector at the top. Most macroeconomics textbooks wait until well into the book to introduce the government sector. That lapse is telling.

Further, debt-deflation theories (such as pure credit models) also abstract from the government sector. But MMT shows that a failure to understand the vertical relationship between the government and non-government sectors leads to spurious conclusions about stocks and flows.

A digression: a flow variable can only be calculated with reference to a time period. So $100 of spending per quarter or year. A stock variable like the unemployment pool has no time dimension so has to be observed at a point in time. Flows feed stocks and so a valid macroeconomic model has to ensure that all the flows it specifies augment/reduce stock variables in a consistent manner.

Several points emerge from this diagram.

First, while central banks appear to be independent of treasury functions, there is no gain in separating the treasury and central bank operations when seeking an understanding of how the monetary system operates. The consolidated government sector determines the flow of net financial assets (denominated in the fiat currency) in and out of the economy.

Treasury operations (spending and taxing) can deliver surpluses (destruction of net financial assets) or deficits (creation of net financial assets). Most central bank operations merely shift non-government financial assets between bank reserves and government bonds (open market operations), so for all practical purposes the central bank is not involved in altering net financial assets.

The exceptions include the central bank purchasing and selling foreign exchange and paying its own operating expenses. While within-government transactions occur, they are of no importance to understanding the vertical relationship between the consolidated government sector (treasury and central bank) and the non-government sector.

Second, we can understand the basic vertical relationships by cutting the diagram off just below the non-government box. Extending the model to distinguish the foreign sector makes no fundamental difference to the analysis and as such the private domestic and foreign sectors can be consolidated into the non-government sector without loss of analytical insight. Foreign transactions are largely distributional in nature. We can thus operate as if the non-government sector is as one. The point here is that all (horizontal) transactions between institutions or entities within the non-government sector net out in an accounting sense to zero – for every asset created there is a corresponding liability.

This is a crucial difference – the vertical transactions between government and non-government do not net to zero – they can create/destroy net financial assets. Understanding that is a key step in being able to make literate and informed comments, whatever your ideological persuasion, about the monetary system and the role of government within it.

Third, the results we derive below is exactly the same when expanding this example by allowing for private income generation, a banking sector and diversifying the non-government sector into a foreign and domestic sector.

Apart from getting the accounting clear and allowing us to avoid making fools of ourselves by saying things like – “the taxpayers will be paying off the debt for years”; or “debt is financing government spending” and related nonsenses; this framework helps us understand that it is the use of state money that introduces the possibility of unemployment.

Unemployment is always a choice of government in a modern monetary economy. It always has the capacity to maintain full employment by ensuring its net spending is sufficient to meet the desire to net save by the Non-Government sector.

When I talk about a modern monetary economy I mean a system with:

- A floating exchange rate, which frees monetary policy from the need to defend foreign exchange reserves;

- Fiat money is the unit of account to pay for goods and services. A fiat currency is convertible only into itself and not legally convertible by government into gold, for instance, as it was under the gold standard.

- A sovereign government that has the exclusive legal right to issue the particular fiat currency which it also demands as payment of taxes.

- A tax system that ensures viability of the fiat currency by dint of the fact that it is the only unit which is acceptable to extinguish tax liabilities and other financial demands of the government.

However, Barney clearly needs some more basic learning tools to get his head around these concepts. It just happens we can simplify the relationship between the government box and the non-government box depicted in the diagram down to some basics. We are going to walk now!

So here is a basic modern monetary economy stripped down to the essentials which will allow us to walk through the government relationship with the non-government sector.

We are going to visit a someone’s house and pry into their affairs for a 6-month period. To preserve anonymity assume it is my house. So lets see what happens in my house in the first month.

Month 1 – no private saving

I decide that I want to instill the work ethic in my children. Yes, I am old-fashioned despite being a hippy. So I devise a plan that I learned from MMT. I call them around the table and say:

Kids, there are always plenty of household tasks to perform and you can earn my business cards if you complete them each month.

The kids respond in unison immediately:

Why would we want to earn your worthless business cards – they are just scraps of paper that you litter conference and meeting floors with.

I then sit back in my chair and suggest that:

Any child who wants to eat and live in the house must pay me, say, 600 business cards each month for the privilege.

The kids respond in unison, almost immediately:

When do we start work?

You can see that by requiring that the children use my cards to fulfill a “tax obligation” I have instantly given value to my cards and real resources transfer from the kids (the “private sector”) to the me (the “public sector”).

Where do the business cards come from? Our modern home has broadband and a local area network and the kids have their own computers and no-one ever really bothers to talk to each other anymore. This is great because efficiency is increased. All our business cards transactions are done via our network and a master spreadsheet is kept which is accessible to all members of the house. This spreadsheet records all the transactions. Business cards are created (for spending) and destroyed (as taxes are collected) with the stroke of a key in a spreadsheet cell.

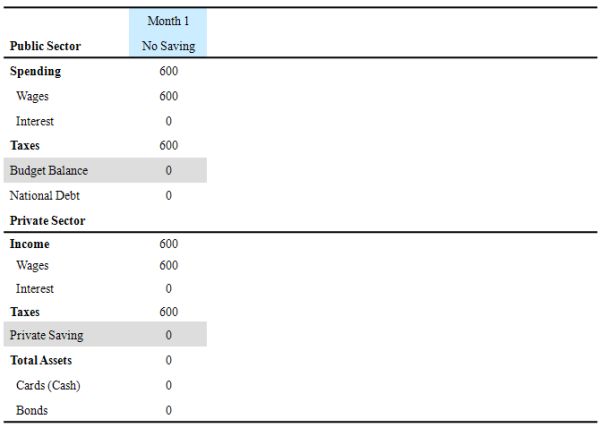

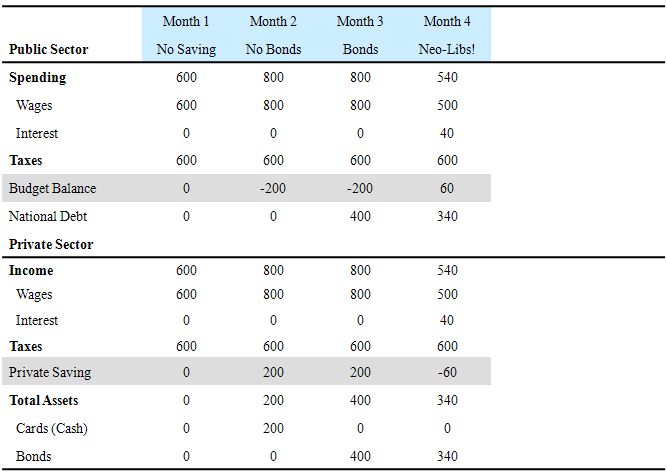

So in the next graphic for Month 1 you can see the summary spreadsheet entries. I have spent 600 cards on wages and raised 600 cards in taxes (this is a one child household).

Principles learned in Month 1

- Until there is spending there is no capacity to pay taxes.

- Taxes function to create the demand for federal expenditures of fiat money, not to raise revenue per se. In fact, a tax will create a demand for at LEAST that amount of federal spending.

- A balanced budget is, from inception, the MINIMUM that can be spent, without a continuous deflation. That is, the kids would not be able to earn at least as much as they needed to pay taxes.

- If the budget is balanced there can be no net saving or net accumulation of financial assets.

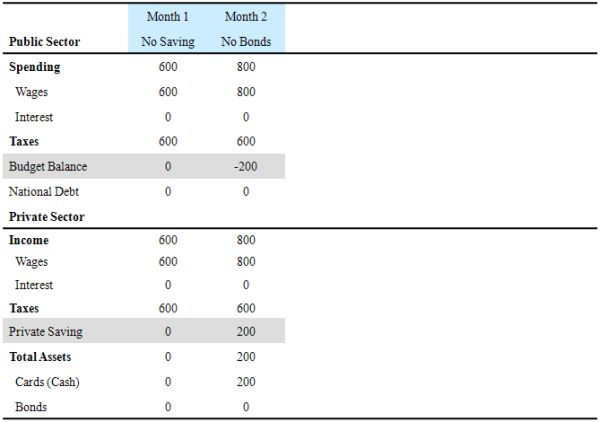

Month 2 – private saving

The kids then want to know how they can save some business cards. They want to be able to earn a few more cards than they need for the immediate tax bill to allow them to have a holiday some months. In multi-kid households, they might want to start doing deals among each other to swap work obligations etc.

What imperative does this introduce? The accounts for Month 2 appear in the next graphic. It is clear that the children’s desire for thrift will force me to run a deficit as a matter of course. They cannot save in the currency unless I am spending more than I tax them.

So the desire increases the level of activity in the economy by 200 cards per month and the extra employment generates higher incomes and permits the children to save 200 cards a month.

Principles learned in Month 2

- Public deficits allow the private sector to net save in the fiat currency and accumulate financial assets. In this case the saving is in the form of non-interest earning business cards.

- The accumulated saving of financial assets is the stock of wealth and reflects the accumulated deficits. Without the deficits, the private sector (the kids) cannot save and accumulate wealth in the currency of issue.

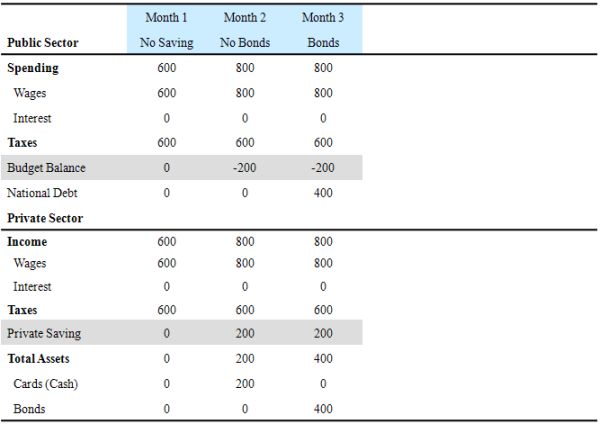

Month 3 – a public debt instrument is created

As it stands, the savings last month of 200 cards will just sit there in the spreadsheet and the kids will not earn anything from the foregone consumption (that is, no interest will be earned).

The saved cards represent holdings of “money” that will allow the kids to not work sometime in the future but in the current situation they will not accumulating (compound). Another way of looking at this is that there is excess liquidity (spare cards) in the overall system and the rate of return is zero (zero interest rate).

The kids might try to get rid of that excess by lending to each other but the competition would maintain the return at zero because they are unable as a “sector” to eliminate the “excess reserves” which arose from my deficit spending.

To reward thrift (preparing my kids for the real world), I call them around the table again and say:

I now propose to pay 10 per cent on all outstanding business cards (payable in more business cards) per month.

The kids soon realise this is a good deal and all extra cards not needed overnight for inter-sibling transactions are instantly deposited in a new account created by me – bond-issues

The kids thus swap the non-interest earning cards for an interest-earning bond. For me it is a matter of just borrowing back some of the business cards from the kids that I have already spent and providing them with a financial asset (bond) in return. We agree in the interests of the environment not to create any paper bond certificates. Everyone is happy that the bonds are recorded in the spreadsheet and have instant maturity (that is, can be converted back into cards at any time).

The business card deposits become the “national debt of the household” and are liabilities that the parent (me) owes to the children. Anytime they wanted to convert them back into non-interest bearing saving deposits they can send me an E-mail and a few clicks later the spreadsheet would reflect their desires. I have no constraint on how many numbers I can type into the spreadsheet.

So the graphic for Month 3 with the newly created public debt instrument is next.

Principles learned in Month 3

- The accumulated public deficits equal the accumulated private savings.

- This in turn equals the accumulated stock of financial assets (which can be split between cards and bonds).

- Without the issuance of the bonds the rate of interest would be zero unless I agreed to pay an interest rate on the saving balances.

- The bonds issued have nothing to do with “financing” my business card spending.

- I am just borrowing back cards that I had previously spent

Month 4 – the neo-liberals invade

One night when the kids are safely sleeping I read some neo-liberal economics literature on the Internet. I had stumbled on a WWW site called billy blog but decided he was nuts and found other sites that were relating things I had read in the paper and heard on the news. It was credible stuff.

The accumulated budget deficits that I had been running in the first three months started to send shock waves down my back. Cut backs were obviously required.

The literature was telling me that I would have to pay higher interest rates on my debt; that inflation would rise; and that the national debt would choke the initiative out of the economy because they would require higher taxation in the future. My plans to help my kids would fail. They would refuse to work and probably turn to drugs.

So I need an exit strategy!

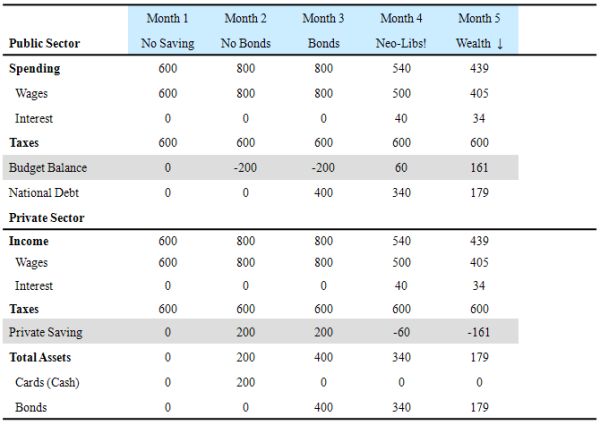

So I implement a cut back in spending because I read that increasing taxes would stifle incentives. I now offer only 500 cards of work in Month 4 and have to pay 40 cards on the outstanding bonds. It is clear that the bond-servicing costs are starting to impinge on my ability to spend on other things given I have to as a matter of priority get the budget back into surplus.

The austerity plans delivers me the cherished budget surplus of 60 cards in Month 4. Total income for the kids is now 540 cards which is comprised on 500 labour wages and 40 interest income on their debt holdings. But they are still liable for 600 cards in taxes.

So where do they get the cards from given they are being squeezed in this month? They sell 60 cards worth of bonds back to me to ensure they can meet their monthly tax obligations.

I reduce the national debt by 60 and smile because I am following my neo-liberal plan to a tee. The kids dis-saved by 60 cards in Month 4 (a flow) and “pay for that dis-saving” by running down their wealth by 60.

Principles learned in Month 4

- If I had stayed reading billy blog I would not have made this error.

- Budget surpluses squeeze the private sector for liquidity and the private sector is forced to run down wealth through negative saving in order to meet their tax obligations.

- Budget surpluses destroy private wealth!

Month 5 – wealth declines

From the neo-liberal perspective, my strategy as the government of the household has been exemplary. I am now generating surpluses and retiring debt. I am no longer living beyond my means.

I fail to notice that the kids’ (private sectors’) wealth is being destroyed and they are unable to work as much as they want. Some Chicago economist wrote that unemployment was voluntary anyway and the kids are probably lazy or just enjoying leisure more now.

I also fail to notice that the kids who hadn’t accumulated any wealth are facing rising debts. They seek to borrow from other kids because their work opportunities are being limited and they have to pay their taxes still.

In Month 5, I also get reinforcement from reading European Central Bank discussion papers; IMF staff papers; World Bank papers; lots of stuff on the Internet from various journalists – I especially study the Greek government profligacy and fail to recognise that my economy is not part of a monetary union and I can spend without revenue constraints.

Anyway, bouyed by my advice I decide that I should wipe out all the national debt. So I extend the fiscal austerity and cut spending to 405 and my interest servicing payments on the outstanding debt is also now lower at 34 cards. I keep my tax regime intact and return a great surplus of 161 cards.

The kids’ income is now only 439 cards (405 wages, 34 interest) and have to pay 600 in taxes. As a result, they dis-save by 161 cards (exactly the surplus I run but I don’t make that connection).

To “finance” this dis-saving, they liquidate 161 bonds and I reduce the spreadsheet entry for their wealth by 161. Private wealth is now at 179 cards as I get the debt monkey of my back.

Principles learned in Month 5

- The reductions in outstanding public debt is systematically reducing the income-earning opportunities for the kids. So not only does the austerity plan reduce employment opportunities it also erodes private fixed-income capacity.

- The budget surpluses continue to destroy wealth by squeezing the private sector of liquidity.

- Some kids will be becoming increasingly indebted.

Month 6 – insolvency

By now I am so imbued with neo-liberal logic that billy blog is accusing me of being a “deficit terrorist”. But we all know he is nuts. Anyway, the austerity plan continues because I want to pay down all the national debt.

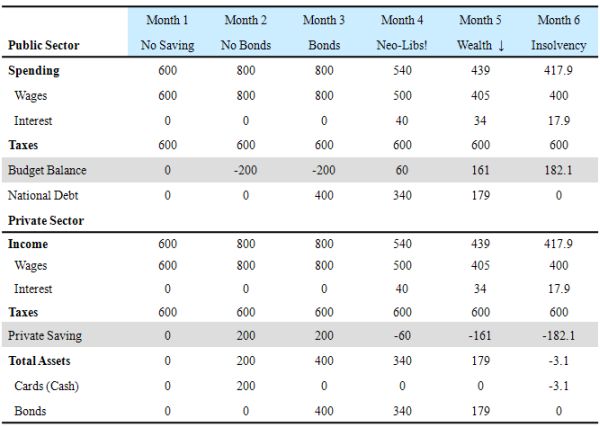

So I cut my wage bill to 418 cards in Month 6 and almost halve the interest payments on public debt that was outstanding at the start of the month. I keep the tax at 600 cards.

I now achieve a wonderful surplus of 182 cards (the exemplar of fiscal prudence).

The kids now dis-save 182 cards but only have 179 cards in bonds that they can liquidate. They are now technically insolvent (having a cash deficit of 3 cards).

But I call them around the table and tell them how wonderful it is that I have retired all our national debt and am now “saving”. They look at me askance – underemployed and insolvent.

Principles learned in Month 6

- The accumulated budget balances equal the accumulated savings in the non-government sector. So if you add each of the deficits and subtract the surpluses you will come up with minus 3 cards. Now saving was achieved after 6 months because the surpluses (destroying private wealth) just offset the earlier deficits (which created private wealth).

- Running surpluses thus forces the private sector to dis-save and private wealth holdings are destroyed as a consequence.

- For a time the kids were able to borrow from each other to maintain their spending (and tax payments) but eventually, their saving is compromised by the falling national income (household wages plus interest payments). The fiscal austerity in each of the last 3 months causes recession and increasing unemployment and ultimately mass insolvency in the private sector.

While some people might try to develop elaborate examples to suggest otherwise the stock-flow accounting is clear and doesn’t matter if you do the analysis in nominal terms or real terms (deflating using a price level). Introducing inflation would not change the fundamental accounting relationships.

You cannot escape the conclusion that when a government budget deficit adds net financial assets (adding to non government savings) available to the private sector and a budget surplus has the opposite effect.

Further, given effective demand is always equal to actual national income, ex post (meaning that all leakages from the national income flow is matched by equivalent injections), the following sectoral flows accounting identity holds:

(G-T) = (S-I) – NX

where the left-hand side depicts the public balance as the difference between government spending G and government taxation T. The right-hand side shows the non-government balance, which is the sum of the private and foreign balances where S is saving, I is investment and NX is net exports. With a consolidated private sector including the foreign sector, total private savings has to equal private investment plus the government budget deficit.

In aggregate, there can be no net savings of financial assets of the non-government sector without cumulative government deficit spending. In a closed economy, NX = 0 and government deficits translate dollar-for-dollar into private domestic surpluses (savings). In an open economy, if we disaggregate the non-government sector into the private and foreign sectors, then total private savings is equal to private investment, the government budget deficit, and net exports, as net exports represent the net financial asset savings of non-residents

It remains true, however, that the only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings) and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save (financial assets) and thus eliminate unemployment is the currency monopolist – the government. It does this by net spending (G > T). Additionally, and contrary to mainstream rhetoric, yet ironically, necessarily consistent with national income accounting, the systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses (G < T) is dollar-for-dollar manifested as declines in non-government savings. If the aim was to boost the savings of the private domestic sector, when net exports are in deficit, then taxes in aggregate would have to be less than total government spending. That is, a budget deficit (G > T) would be required.

Conclusion

That is about as simple as it gets. You should be able to relate this easily to the first diagram.

As background reading I suggest the following blogs – A simple business card economy and What causes mass unemployment?. Further, to map this model into the real world I would recommend you read the following trilogy: Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

That is enough for today!

Excellent. A good tutorial, Bill.

Hi Bill:

Great lesson, your blog is a must read.

Thanks Again.

Mark

great article. As an american, my guess is that Joyce is nicknamed B-Jo in light of J-Lo, the nickname for the celebrity-actress Jennifer Lopez…..

Hi Billy, again I disagree on almost anything although I concur in many of your conclusions … It’s right, the state CAN behave like that, I have never to this date seen this concept spelt out so clearly, and IT WORKS to the extent that you had a Fichtean “closed trade state” (and, to me, a prison). However, as long as there is this “floating exchange rate, which frees monetary policy from the need to defend foreign exchange reserves” you will in the end find that fewer and fewer foreigners will -unlike your children- play ball and then exactly what other monetary theories predict in this case will happen: foreigners will accept your fiat currency for less and less of their own so that in the end import prices rise sky high (of course depending on how much you spend as a government, if you’re thrifty, the process takes longer, and thus many will believe it works, but all curves I’ve seen so far historically ended up in an exponential shape eventually going “through the roof”. And then even your model citizens start to balk and if you don’t resort to the strictest tariffary and customs import restriction measures they will eventually begin a separate black market economy, fines and incarceration r not. So legal tender laws -like any other trade restriction- work for a while, but don’t take one jot away from the fact that paper is paper in the end. You as a father with dependent children can try and play that game and as long as your children accept your business cards as”fair value” they will prefer to stay in your household, however, if, for example, you “charge” ten cards, equivalent of cleaning the whole house, for one lunch and your neighbour offers the equivalent of a decent meal for washing his car, AND you let your kids go about freely (see the prison state) then you’ll see them more and more eating out. So father state then starts giving out vouchers (dole, housing assistance etc.) and drives the uncontent masses back to his “shop” for a happy hour, only to find out, with further devaluation of his currency, he has to up the ante, everstronger doses are needed to “finance” the system’s imbalances and, like all those systems, it will ultimately crash. We both are probably young enough still to find out in this day and age which world view prevails. My take is complete government default, rampant inflation and after some time of tribulation the reinstitution of a backed currency.

Thanks for this Bill – great for thickies like me (and Joyce, no doubt).

What effect do bank loans and asset inflation have on this? For example, a bank gives someone a loan to buy a house, which they later sell for a profit and pay off the loan. Is that resulting profit ultimately only a product of government deficit spending, is it ‘funny money’ based purely on the perceived value of the house, or has ‘money’ actually been created by the non-government sector?

Thanks again.

Hey Bill

Your post “My Sunday Media Nightmare” got a link on Yves Smiths “Naked Capitalism” site (she labeled it her “must read” of the day)!! She has quite a broad readership, at least as large as Mark Thoma’s site. Your message is reaching a larger audience!

She has Marshal Auerback on there pretty regularly so I wonder if you might not offer her a few guest posts? As an aside, when the president had a few financial bloggers in to the White House last fall, I think it was 8 of them, Yves was one of them, so she has been noticed by the powers that be.

Here is a review of the meeting with Treasury officials and bloggers by Steve Waldman tp://www.interfluidity.com/v2/214.html

I feel the tide may be starting to change.

superb

Bill,

I sent that link to Yves and was glad she posted it.

Many comments also, for a link.

A while back I also sent her the link to the 77 min. video of yourself and Randall Wray, teaching it up.

I found Randall’s oral-translaton in that video (the Buck-aroos) of the picture you paint here to be worth two-thousand words.

Maybe three. Probably easier comprehension for the younger crowd to ‘get’.

You are getting closer, Bill.

So, get that book done.

Just in time.

Wow! Bravo, Bill.

This is going right up at the top of my glossary of links, right along with Stock-flow consistent macro models. I can’t wait for the book to come out.

Greg, I agree, this balloon seems to be filling up with helium, thanks to the work in the blogosphere of Bill, JKH, Ramanan, Randy, Scott, Warren, and Winterspeak, especially, but also a lot of others getting the word out. (It was though a comment by Ramanan somewhere that I rather accidently got here.) This is happening not a moment too soon. The ship of state is taking on water fast.

pardon my ignorance if this is patently obvious, but i have a simple question: why do you issue $400 in debt to soak up just $200 in excess reserves? what am i missing here?

Lets assume I agree with this thesis. The implication of this therefore is that govt can deficit spend its way to full employment and no recessions whatsoever regardless of private sector profligacy i.e. since the govt can create money out of nothing (in a fiat economy), regardless of the fact that the private sector does nothing but use the money to inflate assets w/o doing anything “useful” and “productive”, and there will be no recession and no unemployment. Hallelujah! Utopia.

Of course, you assumed in month 1 that the kids need to “work” i.e. govt could print money (electronicaly credit accounts, whatever) AND ensure that the private sector actually used that money for productive purposes. The problem is that there are different “types” of kids. Some kids work, generate productive goods and services. But some kids just turn around, use the money to inflate asset values and live (or try to live!) off the income from these assets. What then results is asset values get inflated beyond their true economic value. Which is where we are now – in US, in Australia, in China. And then, asset values decline (some of these kids who inflated these asset values decide that they have inflated assets sufficiently or that they cannot inflate any more and sell!). Unfortunately, this affects ALL the kids.

The govt then panics, prints more money in an effort to keep asset values inflated i.e. get those kids who were selling not to sell. This seems to stabilize things. Unfortunately, these kids aren’t still “working” so there is still no economic and productive value being created. Eventually, this ponzi scheme of inflating asset values created out of easy money policies fails. Say month 25. And then the easy money just chases goods and results in inflation.

The lesson – malinvestment created by printed money is the flaw in this nice theory. Lesson 2 – just printing money if not supported by productive use of that money (kids don’t work but try to live off inflated assets and the income that these inflated assets generate) will fail. You can’t create value out of just printed money if it is malinvested.

If the govt could channel the money it prints into productive uses throughout the private economy every time (or majority of the time I guess), then this is great. Alas, this theoretical model will fail in the real world. The end result will be severe inflation.

I am no economist and have only recently been introduced to MMT, so if I am absolutely dead wrong and am a moron who doesn’t understand this and am drawing all the wrong conclusions, please educate me. I am fully willing to eat crow and bow before the people on this blog who understand all this much better than I do.

Dear William N.

Thanks for your question. Early in this blog I distinguished between stocks and flows. The answer to your question reflects on that distinction to some extent.

The bond issues (400 cards) were in relation to the accumulated card wealth holdings (a stock) that the kids had after two months of deficits (flows) which amounted to 400 cards. In each of those two months, the deficits were 200 (a flow) which allowed the kids to save (a flow) 200 cards per month. These monthly flows accumulated into the 400 card stock of reserves.

The general point being made is that the accumulated stock of currency-denominated wealth reflects the pattern of past deficits.

best wishes

bill

understood. thanks

Yes Bill, what effect does bank lending have on the way the system operates? If the central bank is accommodating loan demand at a desired overnight interest rate, won’t people be able to pay their taxes with some fraction of the loan money?

I’ve been slowly working on a tool to help with visualizing some of these concepts. I’ve been torn as to whether to put a draft out there or work on it longer first, but decided today just to put a copy up, imperfect and incomplete. (I was partly inspired to see Bill doing a particularly visual and accessible post like this one).

Here it is:

http://econviz.com/bsexplorer.html

All you MMT experts (stf, jkh, etc) especially — I’d love you to correct me on anything I have wrong so far, feel free to suggest what you think are the highest priority additions to extend breadth but also make what’s there more accessible. You can email me or comment at this placeholder post. Or here I suppose but I figured it wouldn’t be polite to pollute this comment thread too much 🙂

haris07, what you describe is happening as we speak. Investment in production is declining in the developed countries and finance is increasing. This involves rent-seeking on the part of FIRE, which is wealth extraction, much of which is used in asset markets to seek greater gains through leverage. This is described in Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis as the third and final stage of a long financial that is characterized by Ponzi finance. It happened leading up to the Great Depression, as Irving Fisher described in his debt-deflation theory of depressions, and it led up to the current GFC.

This is not a failure of fiat money, it is a failure of advanced capitalism that has “progressed” from entrepreneurialism and productive innovation to financialization and financial innovation. The answer is regulation to police the system and negative incentives, e.g., targeted taxation to reduce inefficiencies introduced by finance, especially aspects of finance that do not promote investment or divert funds from it. The notion that leaving the present system as it is would obviate what you describe is just not borne out by experience. I don’t see this “problem” as something MMT would introduce or make any worse than already exists and has long existed under a variety of monetary regimes.

MMT isn’t calling for a revision of the present monetary regime. It is simply describing how what is in place since Nixon shut the gold window actually operates and suggests taking advantage of unrecognized options. MMT primarily corrects erroneous ideas. based on a hangover from the days of convertibility and fixed rates, concerning how things work now under the non-convertible flexible rate system that is in place. With this knowledge it is possible to make more informed economic and policy decisions.

Chris

I hope Bill or someone else more qualified than myself takes on your post. It is a story that is told by many people who are leery of fiat currencies. I am going to attempt to address it.

The mistake I think you are making is that you see the problem as one of with the type of currency. The problem is the people. We certainly were not devoid of financial crises under the gold standard. We certainly were not devoid of greedy politicians or politicians captured by private interests. Competition with foreign interests would not go away with a “backed” currency. The truth is in the complex world we live in right now a whole new economic paradigm is called for. All the developing countries are seeking the same things for their citizens and whole new levels of organization need to be created. When we backed currencies with gold, countries that “owed” gold to other countries from trade deficits had to transport bullion to them. How fricken crazy is that?? Armadas were used to simply take gold to another bank vault, what a waste. So what are you going to back it with and will it be necessary to actually exchange the good backing it when trade deficits result? If you dont require the good to be exchanged and simply tally it or trust them for it later, have you really changed anything. How would you ever know they had the backing for it.

My point is the answer is not really in the type of currency but the type of people and the system of checks and balances you employ to validate transactions. All MMT verifies for me is that there is not a fixed amount of money in the world. It doesnt say you should spend it on anything you want, in fact if you follow Bills blog its quite clear that he thinks spending responsibly is paramount for a currency issuer. Part of that responsibility is making sure that all your labor force that wishes to produce CAN and does.

Dear haris07

No bowing and scraping is required on this blog – all are equal. We just bring different experiences.

First, I am not sure what the expression “asset values get inflated beyond their true economic value” means. In a market system, the price people are willing to pay reflects the “value” they place in the good or service. But given that the concept of rents can apply such that the person may have been willing to supply the good or service at a much lower price. But the fact remains it is hard to determine “true economic value” independent of the bid price in the market – especially when the assets is intrinsic (that is, not related to underlying fundamentals such as a share price is).

Second, we must differentiate inflation from the price escalation of a specific asset class. It is a common misperception that when real estate bubbles occur this is inflation. It is not. Inflation is a continuous increase in the level of general prices. A real estate boom is a relative price change unless all prices rise in proportion. So to jump from a scenario where some specific asset class is booming to a statement that “easy money chases goods and results in inflation” is not a valid inferential sequence.

Third, clearly, and I have said this regularly, if government spending (or any component of aggregate demand – that is, private spending or net exports) push nominal demand faster than the real capacity of the economy to absorb that spending and respond with real output increases then inflation will result. That risk is not intrinsic nor exclusive to government spending. Again a common misperception.

Fourth, you are assuming that fiscal policy cannot be targetted. The simple example I gave in this blog is just a wage payment. But government spending can be very tightly targetted to avoid the sorts of issues you raise. Further, the role of taxation (either income or other (like capital gains etc)) is to deal with the sorts of specific issues you raise. In a mixed economy, private spending can clearly be wasteful and not develop productive capacity. The solution is to have less private spending of that type and fiscal policy can achieve that compositional shift.

Fifth, I have advocated a widespread financial market reform agenda which would eliminate the majority of speculative ventures that you are worried about and get investment focused back onto the creation of productive capacity. The problem with late C20th capitalism under the neo-liberal paradigm is that it encouraged financial market speculation which then was focused on specific asset classes and was not linked to productive activity.

As I see it, none of the points you have made undermine the concepts that I develop under the guise of MMT, which after all is just a clarification of how the monetary system operates not some ideal world. My aim is to expose the fallacies that exist in the modern debate. I aim to show people that what they think and are told are financial constraints are in fact just political constraints which should be compared to other politicial decisions – like running harsh austerity programs that impoverish generations of people. Once people understand that some of these so-called financial constraints are political choices then the comparisons become more stark and government may act differently.

best wishes

bill

If the central bank is accommodating loan demand at a desired overnight interest rate, won’t people be able to pay their taxes with some fraction of the loan money?

The way I understand it is that bank money and government money are different systemically, but appear the same in a modern economy because the government allows the commercial banking system to use its unit of account (e.g., the dollar) and its cash (in the US, FR notes and minted coin). But this doesn’t mean that bank money and government currency operate in the same way systemically. MMT shows how they don’t.

All bank money is created by loans (loans create deposits), so everyone bank money is someone else’s loan obligation. All the bank money is required to service the loans in the banking sector, and even more lending is required to service the interest that is compounding, increasing the obligations in excess of the deposits that created bank money.

Conversely, government currency issuance creates non-government net financial assets, and the government periodically withdraws some of what it creates through taxation. Systemically, only NFA are available to satisfy obligations to the government. IN the first place, the government only accepts its own currency in payment of obligations, and secondly, there is no bak money left over to do so. This is obscured on the micro level, but it holds at the macro level.

This would be clear in a system that distinguished between government issuance and bank money, in which case to pay taxes, one would have to exchange bank money for government money. But this distinction is obscured in the present system since only one form of money is used for both purposes, but it still holds systemically.

CrisisMaven, we live in a world of non-convertible floating rate currencies and have for some time. There are no “sound money” currencies available. The sound money people go to gold and forgo the interest, I guess.

Moreover, what you describe should have happened to Japan but did not. They have been running a huge national debt to GDP ratio for some time, and they have no inflation (deflation is there problem). Japanese bonds always find buyers at very low rates, and, borrowing cost are so low, the yen is the vehicle for a flourishing carry trade. Japan is not an inflation pariah. ???

On the inflationista reasoning, German bonds would be a better place to be instead of US bonds, since there would be lower risk, given German inflation-phobia, resulting in tight policy. Actually PIMCO honcho Mohammed El-Erian is advising to switching from US Tsy’s to German bonds because of the “lower risk.” But as Mike Norman point out here, the US as monetarily sovereign can never default, other than by choice, since its currency issuance is not constrained financially. However, Germany, not being monetarily sovereign, can default, however low the risk of default may appear now. Did Dr. El-Erian overlook that, or did he forget to mention it as a caveat?

What about Zimbabwe, you say? Bill’s anticipates this in Zimbabwe for hyperventpilators 101.

Thinking about asset bubbles….

An asset is a store of value. That’s what it’s for, it doesn’t contribute to its owner’s current consumption, but it allows him to store value to support future consumption. I can think of at least three asset classes: Currency/deposits/govt debt; private debt (corporate bonds, MBSs, etc); and physical stuff like gold, real estate, artworks, etc (stocks belong here too, representing a share of a company rather than a fixed number of dollars). Bill points out that the second category nets to zero, and I’m willing to ignore it. Besides, market prices are naturally capped at face value, so a “bubble” in the price of corporate bonds is impossible. The last category, physical assets, is not denominated in the unit of currency, so it’s not a “financial asset” in the sense that only deficit spending can create net financial assets. But it is still a store of value, it’s price can change, and in fact it’s the asset class which is subject to bubbles.

Let’s distinguish between (micro level) spending on consumption goods/services and spending on assets i.e. saving. Suppose my income is 100, and I spend 90 on consumption, either saving 10 in the bank or purchasing 10 worth of some physical asset. Now I get a raise, and my income is 110. I might decide to consume 95 and save 15 (my marginal utility from the 96th unit of consumption and the 16th unit of savings are the same). So my demand for consumables/services — things that represent other peoples incomes — has only climbed about 5%, but I’m putting 50% more money towards assets.

Now imagine that I’m typical: on average, people’s income elasticity of saving is much larger than their elasticity of consumption. If the govt decides to add money to the system in some nonspecific way — broad-based tax cuts, for example — aggregate demand will only be pushed up by a small fraction, so production will only rise a little bit. But substantially more money will now be chasing the same pool of physical assets (assuming people try to keep their portfolios balanced, rather than allotting the entire increase to govt bonds), and their prices could rise dramatically.

So easy money can produce asset “bubbles” without driving inflation in the price of consumption goods/services — and maybe the stimulation wasn’t even enough to reach full employment, and there’s no generalized inflation. Anyway, I don’t know if this is happening, or would happen with further stimulus. But it certainly seems theoretically reasonable. (And this is before accounting for people’s tendency to prefer appreciating assets which can lead to positive feedback within a particular asset class).

Bill; Could you possibly shed more light on your following statement, with specific reference to the financial condition of the PIIGS group, and perhaps most immediately, the loss of confidence in ability for Greece to meet its debt obligations? Some of the proposed bail-out conditions seem Draconian . . .

>>My aim is to expose the fallacies that exist in the modern debate. I aim to show people that what they think and are told are financial constraints are in fact just political constraints which should be compared to other politicial decisions – like running harsh austerity programs that impoverish generations of people. Once people understand that some of these so-called financial constraints are political choices then the comparisons become more stark and government may act differently.<<

lilnev, when you talk about savings in physical assets or private sector assets (bonds, stocks, etc) it all nets out to zero. If you buy with your 10 some piece of a physical asset then the seller will get your 10. Private sector in aggregate saved 0 but redistributed physical assets and _real_ savings which is government issued financial assets (money and bonds). This just means that what you call saving is in reality spending. And it is not about storing of value because value is defined by demand and supply. These two variables are to be regulated by the government (though obviously more on the demand side than on the supply side).

To give an example. If government spends more than private sector wants to save then there is more demand (more money) for the same supply and prices have to increase. In USA in Q3 private sector had saving desire of 11.3% GDP (4.9% foreign sector, 4.8% personal savings, 3.3% corporate) while budget deficit was lower and I think 9.9% but might be wrong here. This leads to lower demand with given supply which leads to lower production in the next period and then lay-offs.

Bill,

Thanks for making the points. I understand your thesis and it makes sense and I am certainly not suggesting anything to undermine your main points. What I remain unconvinced is that the govt spending will be targeted to productive uses (at the margin maybe, but doesn’t seem to be the case in majority of the cases) rather than creating asset bubbles. Whether these asset bubbles themselves lead to inflation…that I am not too sure of. Putting aside technical definitions of inflation, I’d argue that the way inflation (at least in the US) is calculated is incorrect in that it excludes home price appreciation and hence understates inflation. Same thing with a focus on “core” (as if people don’t eat and use energy!). But regardless of whether asset inflation causes general inflation or not, the problem with govt spending remains that it has been channeled to unproductive asset bubbles. When real capacity of the economy isn’t increasing and deamnd is, this will result in inflation (per your own point).

If this can be rectified with adequate regulatory reform and effective fiscal policy targeting, then perhaps this works.

Separately, what’s your opinion that Rogoff & Reinhart as well as Niall Fergusson’s research and books that reach the conclusion that eventually printing currency leads to inflation and effective default on fiscal debt by currency debasement?

All of this gets back to the practical drawback of deficit spending and monetary QE and MMT – since the economy is composed of millions of people and billions of transactions and a few control the credit channel, these cannot be effectively targeted. Financial regulatory reform is incapable of preventing malinvestment. Ergo, inflation will eventually result. This isn’t to undermine your theory, which is far better in explaining the modern fiat monetary regime than arcane gold standard based theories, but to suggest that its application in practice remains out of reach of the world.

Thanks again.

haris07: What I remain unconvinced is that the govt spending will be targeted to productive uses (at the margin maybe, but doesn’t seem to be the case in majority of the cases) rather than creating asset bubbles.

As I pointed out, this is also true of bank money. However, I appreciate the question you are asking, which I interpret as being more about productive investment than asset bubbles (not “inflation”), which have arisen in every system. This is a legitimate and important question that progressives must answer in disagreeing with conservatives about the proper role of government and real limitations on government activity in practical terms.

First, the notion that non-government investment is highly productive under capitalism is questionable considering that 90% of business fail in rather short order and all businesses fail in the long run, or morphed into something else that merely bears the original name. Every entrepreneur and venture capitalist knows the enormous sums that just evaporate. Secondly, business are not necessarily managed efficiently, especially large ones. That is a chimera. A lot of the so-called efficiency involves transfer of resources to top management and executives through various perks at the expense of powerless shareholders and workers with little bargaining power.

The issue is not so much efficiency as effectiveness. An organization that is highly efficient is not necessarily highly effective. “Efficiency is doing things right, and effectiveness is doing the right thing.” It is often necessary to accept some inefficiencies in the interest of effectiveness. The military is a good example. It attempts to maximize efficiency in relation to the mission, not to optimize it. Every well managed organization is like this to some degree. Engineers know from experience that optimize efficiency and effectiveness is a heuristic ideal, not a practical goal.

As a system grows beyond a certain point greater inefficiency results as a law of diminishing returns, so to speak. Conservatives often overlook this in their theories. But it is a reality.

Governments have a constitutional obligation to pursue public purpose as mandated. The preamble to the US Constitution states: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” The rest of the Constitution lays down the foundation for doing this.

Promoting the general welfare is a constitutional mandate in progressives’ eyes. This means pursuing public purpose in areas in which private interests either are unwilling or unable to do this, or cannot deliver a result that is satisfactory because their obligation is to shareholders, not citizens. It is agreed by both sides that this includes fundamental areas. Only the proportionality is disputed.

These areas include but are not limited to advancing education, health and welfare, infrastructure, energy, transportation, commerce, basic research, public lands and resources, etc. Most of these areas are already represented by departments and agencies. So we are not talking about instituting anything new here. This is already has a long history, and many successes have been racked up.

The issue is whether it is financially possible to pursue public purpose in lagging areas through better understanding of how the monetary system operates. MMT suggests that it is, and that conservative argument to the contrary are simply mistaken because they contradict fact. For example, the “we can’t afford it” objection falls apart when it is shown that an investment funds itself and returns far in excess of the investment. Education is a case in point. Progressive can meet conservative objections in such areas by pointing out that this is a matter of national competitiveness (“Do you want the US to fall behind?) and also a matter of national security (“Power is based on resources”).

MMT is not specifically concerned with things like project management, regulation and oversight and such non-monetary concerns. Efficiency is a matter of administration and management, not finance or economics per se. Economic arguments (dogmas) that the private sector can do a “better” job than the government have to be evaluated case by case on the basis of fact, not political theater driven by myths rather than facts.

The question is what can be accomplished to maximize the real output potential of the economy through government action without leading to inflation or deflation. This involves questions like yours and many others. These questions are the same whether the government is involved or not. Similar problems arise in every case of policy-making that have to be addressed. Bill actually investigated the recent asset bubble in housing and concluded that it was not government action that was chiefly responsible but playing loose. He is not alone, and people like William K. Black and Karl Denninger have been documenting this. Hyman Minsky and John Kenneth Galbraith warned about this progression of advanced capitalism some time ago. PK/MMT saw it coming too, whereas neoliberalism is still in denial, looking for excuses as to why it could not foresee the GFC building up before its eyes. Answer: neoliberalism did not include finance in its models, and therefore was blindsided to the Ponzi finance developing at the tail of a long financial cycle as described by Minsky in his financial instability hypothesis. MMT do not make this mistake. See Jamie Galbraith’s article, Who are these economists anyway? So I would be a lot less concerned about asset bubbles developing if MMT were understood and implemented in a progressive fashion. But I would also rather have it implemented in a more conservative way than to continue the present nonsense.

Tom

Agreed. Whether MMT is implemented in a conservative or progressive fashion, just implement it.

Very nice comment and its the second time in the last couple days I’ve seen you bring up Denninger. Whats your take on him? I followed his blog a lot for a while but he seems to be a bit of an alarmist regarding govt debt levels as well. He is definitely a no nonsense kind of guy and very thoughtful but he doesnt seem like he’s much help to the MMT cause. What say you?

Tom, your point about efficiency is well taken too. If I had a nickel for every time one of my conservative friends harped on efficiency Id be rich. The other day I did use your quote about efficiency and effectiveness which definitely gave pause to my “opponent”. I couldnt remember who you attributed it to.

Denninger doesn’t get the way the monetary system operates, and he also has a conservative bent, as one would expect a successful entrepreneur might. However, his analysis is irrelevant to the facts he presents about what he refers to the as “the bezzle,” short for “embezzlement,” which he uses as a blanket term for Ponzi activity, including all the misrepresentation, predation, fraud and the rest. “The term “bezzle” was coined by John K. Galbraith in The Great Crash: 1929. JKG claimed that the bezzle is always in play, but it crests in the Ponzi finance stage of a financial cycle.

I think that if Karl got MMT he would be a great proponent of it. He is really committed to principle and aggressively tenacious about it, like Rep. Kucinich, and Rep. Grayson.

Greg, “Efficiency is doing the right thing, and effectiveness is doing things right,” is a quoted attributed to Peter F. Drucker, the management über-guru. It appears in many hits on a search, but so far, I’ve been unable to find a citation of the source document. If anyone knows this, I’d like to have it.

Sergei, thanks for the response. I understand that spending on physical assets doesn’t qualify as net private sector savings for purposes of Bill’s favorite accounting identity, and that asset price levels really don’t enter into the discussion here. I think that’s a shortcoming, because asset prices do matter — they enter into “net worth” and affect the priorities attached to spending vs. saving, for example.

My point was that:

1) At the micro level, spending on physical assets is a good substitute for saving financial assets. I put $200/month into a mutual fund and call it “saving”.

2) At the macro level, the “demand for net savings” is perhaps better understood as a “demand for increasing net worth”. Americans were quite happy not to save while the valuations on housing were rising. A big part of the sudden surge in private savings is a response to falling asset values, as individuals try to rebuild the nest egg in time for retirement.

3) So I think it’s worth trying to understand what drives asset prices. Specifically, there’s an idea out there (see harris07’s comment of 4:42) that “easy money” — either larger deficits or inappropriately low rates — drives up asset prices rather than resulting in an increase in production. So I thought it through, and concluded that there will be a rise in production (asset sales from one private party to another net to zero, so demand for products/services will rise), but that asset prices may rise as a side effect — and furthermore, it’s possible that that price rise will be dramatically larger than the rise in production.

Hilarious! .. But so true of the academicians, central bankers and policy makers. They still do not realize any of this even after the crisis!

Tom I think you got the efficiency/effectiveness thing backwards. When I originally saw you post it (and what I quoted),it was effectiveness was doing the right thing and efficiency was doing things right. I like that way better anyway.

Greg, I did get it backwards, as you say. Senior moment. Sorry.

Should be: “Efficiency is doing things right, and effectiveness is doing the right thing.”

Peter F. Drucker.

It is a an accounting error to view bond sales as an interest bearing demand account. Bond sales and the payment of interest on bonds do not increase or decrease the net worth of those who buy the bonds. Each coupon payment reduces the value of the bond, and all that is happening is a portfolio shift, not an increase in net worth. On the other hand, having the government pay interest on the reserves does increase the net worth of banks — that is corporate welfare, as you say. The reason for the latter is opportunity cost. Banks have no choice but to hold reserves at whatever level the government sets, and therefore there is no lost opportunity by holding reserves. Neither does the payment of reserves affect the quantity of loans made or the terms of the loans in a system in which banks do not lend reserves.

If excessive debt payments bother you as corporate welfare, then be aware that the welfare occurred when the deficit spending was made. It was at that point when the financial assets of the private sector increased. The issue of bond sales is merely a question of the type of government liability (cash or debt) that you are adding to the private sector, not the balance sheet value of the subsidy.

Tom, I’m still not understanding.

All bank money is created by loans (loans create deposits), so everyone bank money is someone else’s loan obligation. All the bank money is required to service the loans in the banking sector, and even more lending is required to service the interest that is compounding, increasing the obligations in excess of the deposits that created bank money.

Bank money can be expanded to pay interest, but not taxes? This leads to a related question, does capitalism depend on economic growth?

Tom Hickey, I am still putting together my “board” idea.

It would be similar to the fed, but the persons on it would be elected by the people.

I need to think about how to fund it because eventually I want as little debt as possible in the economy.

Here is one last thing. It seems to me that the fed is set up to price inflate with private debt. That would need to change.

If I’m reading this correctly, it appears that the national debt is held onto. Doesn’t it usually get spent so that the gov’t needs to earn back both the principal and the interest?

I believe you need to change this ((G-T) = (S-I) – NX) slightly to see what is really going on. Let’s go with NX=0.

(G-T) = (S-I) of the rich plus (S-I) of the lower and middle class. Take the lower and middle class to the other side.

(G-T) minus (S-I) of the lower and middle class = (S-I) of the rich

That is dissaving of the gov’t plus dissaving of the lower and middle class = savings of the rich.

Sound right, and does that seem to be what is really going on?

Can wealth/income inequality, real earnings growth, price inflation, price inflation targeting, and changes in the date(s) of the ability to retire be worked into this model? I believe the model would get REAL interesting then, as in Michael Hudson interesting.

Fed Up: If I’m reading this correctly, it appears that the national debt is held onto. Doesn’t it usually get spent so that the gov’t needs to earn back both the principal and the interest?

The national debt represents the savings (net financial assets) of non-government. These savings have come from currency issued through government expenditure. The debt issuance does not “fund” the currency issuance, because the government has the power to just issue currency. That’s what “fiat currency” means. Similarly, the interest paid on the debt is paid through currency issuance and it becomes part of the net financial assets of non-government that are saved as debt.

NOTHING is “owed.” When the debt comes “due”, that is, the Treasury security matures, the Fed simply switches the “debt” to the reserve account of the holder’s bank, and that enters the commercial banking system as a corresponding increase of the now former holder’s deposit account. It is simply switching a “time deposit” into a demand deposit.

All the handwringing about “borrowing” is just smoke, because government “debt” and “borrowing” are completely different from the debt and borrowing of firms, households and states in the US who are currency users, while the government is the currency issuer. The currency issuer just issues currency like a scorekeeper puts up points on a scoreboard. The points don’t come from anywhere and don’t go anywhere when they are changed or taken down.

That is dissaving of the gov’t plus dissaving of the lower and middle class = savings of the rich.

The government deficit resulting from currency issuance through government expenditure represents the amount of net financial assets that are increased in non-government after taxes. This is offset by debt issuance (Tsy’s of various denominations). The net financial asset increase from deficit spending exactly equals the debt issuance. The debt issuance is the saving by non-government of the amount of net financial assets that have been created by the deficit. It’s a switch of one asset form into another. Intially, government expenditures show up as someone’s demand deposit. These demand deposits are spent or saved, and the funds flow into money saved in the form of Tsy’s. The macro effect of this is that the reserves created by the government expenditures as a deficit end up in Tsy’s, a kind of “time deposit.” It’s like switching a demand deposit (money in a checking account) to a CD for the interest.

This article says something similar to the main post – in a different way/language.

What Henry Paulson’s new memoir misses about his own responsibility for the global meltdown

The main problem with this fast-paced book was the main problem with Paulson’s tenure-a surprising inability to see the big picture.

Excellent Excellent! No words to describe this one! I was trying to engage a couple of interested folks yesterday about how govt surpluses destroyed private wealth. Its funny how people don’t even realize and there is still a great tendency to immediately compare modern economies like US to Zimbabwe and Uganda and not Japan. And when you do mention Japan, they say yeah Japan has been different but you know all their debt is domestic and they are sitting on a timebomb because the population is ageing. Hopefully someday all these neoliberals will realize how dumb they have been.

Vinodh

Tom Hickey & others, I’m not getting it.

First, I’m assuming cards are equivalent to currency. Is that correct?

Next, let me try it this way. Let’s assume there is no gov’t other than currency and debt. That is G=0 and T=0. What would the model look like?

Fed Up: First, I’m assuming cards are equivalent to currency. Is that correct?

Yes.

If G=O there there are no cards (currency issued). If there are no cards (currency) then T=0, because there can be no taxes, since cards (currency) are needed to pay the taxes that can only be paid in cards (currency of issue).

I think you are confused because you not separating in your mind government “money” (currency of issue) from bank money created by lending (loans create deposits). This is confusing in a modern economy because the two types of money are denominated in the currency of issue as unit of exchange, and the cash used as a medium of exchange in cash transactions comes from the government, in the US, FR notes and minted coin. However, they are very different as money, and calling them “money” further confused the issues.

Government issued currency increases non-government net financial assets and bank money does not, since all bank money is someone else’s loan and this nets to zero. However, being based on commercial loans which are interest-bearing, bank money can only fund the required interest through more lending, so people have to go into more commercial debt to service the interest. This funnels bank money to the top. In addition, the interest on government money is paid on bills and bonds, which the wealthy use to park their excess liquidity at interest. So both government and commercial interest benefit the upper echelon of society since the interest paid compounds their wealth. This is what Michael Hudson, for example, is talking about.

This is confusing and difficult to sort out and the people at the top like it that way, since the people at the bottom don’t really know what is going on and can be easily fooled.

“Debt” and “borrowing”–and “spending” and “deficit.” Modern monetary theory needs a new vocabulary. The connotations of those words are negative; to combat them is an uphill battle. Say “government issue of bank credits” instead of “spending,” for instance, or something of the kind.

Tom Hickey said: “I think you are confused because you not separating in your mind government “money” (currency of issue) from bank money created by lending (loans create deposits).”

I sort of have this. In the back of my mind, I want to make the federal gov’t a user of currency just like the state and local gov’ts. I think I am trying to find a way to get currency into circulation that bypasses the gov’t and the banking system.

Jon said: “”Debt” and “borrowing”-and “spending” and “deficit.” Modern monetary theory needs a new vocabulary. ”

Definitely!!! When most people hear the term deficit, they think gov’t debt that has an interest rate attached and will probably mean tax increases and/or spending cuts in the future.

IMO, here is a better way to say it. Assuming a positive price inflation target and if positive productivity growth and cheap labor produce price deflation, how should the fungible money supply expand, with more currency or more debt? What are the differences between the two?

I’m hoping to expand on this example to demonstrate what I am trying to say.

Jon said: “”Debt” and “borrowing”-and “spending” and “deficit.” Modern monetary theory needs a new vocabulary. ”

Absolutely. These pre-fiat currency terms elicit knee-jerk reactions. For instance deficit spending is “bad.” And how’s this one, “Mosler’s idea is for the government to print money.” “Print money!” People don’t realize this phrase is now meaningless. Why try to fight it on its ground? Use different terminology that is more transparent to the actual meaning. “Spending” money into the economy is a particularly non-transparent term. It suggests nothing of what is actually occurring. “Deficit spending” just compounds the problem. It sounds ominous. How can you possibly attach the positive meaning it actually has to such a term?

Fed Up: In the back of my mind, I want to make the federal gov’t a user of currency just like the state and local gov’ts. I think I am trying to find a way to get currency into circulation that bypasses the gov’t and the banking system.

I think that you are attacking a straw man, based on the confusion that arises from the household/government finance analogy, which arises from using similar terms for entirely different systems, giving the impression that people are getting ripped off when that is not in the case, in that way, that is. But this misunderstanding is the basis for many other type of rip-off.

Rather than changing the monetary system, which is very difficult if not impossible, it’s a lot simpler to remove the ignorance, and using different words for different things is a good way to remove the confusion, as Jon and Jim say.

Idealized models look great in an insular economy in which there are no cross-border flows and no trade.

Of course the real world doesn’t work that way, just as this is the case for those who claim that Keynesian policies “work” – they would, IF you could actually get a politician to run a primary surplus as a means of damping demand (and refilling the treasury) during booms! Since that will simply never happen…

Indeed, the intersection of Keynesian thought and what you’ve written above is the essence of the beliefs of folks like Summers, Krugman, et.al. The government can spend itself to prosperity since it creates final demand though expansion of the money (credit) supply at the primary level.

Nice thought – now tell me why it didn’t work in Japan (which has spent 20 years practicing this policy.) The reason is that Japan, like all other nations, do not live in an idealized, insular economy with a bubble around their borders preventing all cross-border flows. This is allegedly accounted for in the above but fails to recognize that the central premise – that the government has effective control of monetary value (via the tax and legal tender function) **becomes void at the border of that nation.**

When one begins with a postulate that ignores the confounding factors one comes to the wrong conclusions. This is the same error (although expressed differently) as arguing that the classical economic equation MV = PQ is correct, where “M” is money supply. Bzzzzt – in all modern economic systems “M” is **CREDIT** supply, and the proof of same is trivially found in every person’s wallet, yet we still have economics texts and classes that teach utter nonsense.

I’m on vacation this weekend but that’s the short version… if this filters to the top of my stack come next week I’ll back to it…

Karl,

Apparently you missed the fact that Bill repeatedly pointed out this was a SIMPLE model aimed at isolating a particular point or two that had come up in comments to previous posts. There are probably several dozens of posts over the last year to this blog regarding the “cross-border flows and trade” you lament are absent here. Why not critique what this blogpost actually says, then go look at the others and critique what they actually say, instead of assuming you have any insight into the limitations of Bill’s more overarching understanding of these issues (which you so clearly don’t) before you’ve actually gone to look for yourself?

Karl:Indeed, the intersection of Keynesian thought and what you’ve written above is the essence of the beliefs of folks like Summers, Krugman, et.al.

Would it were so. There are no mainstream economists or politicians either in the media or close to policy-making that get even this simple model (but profound) model. Or if they do, there are hiding the fact very well.

Our concern here is with “the last mile,” that is, getting this distinction between government as sovereign currency issuer and non-government as currency users, including trading partners doing business with the country, to the people who shape public opinion and have a role in policy-making, as well as getting them to understand the policy implications in terms of options. Based on what they say publicly, virtually all those being taken serious in the media, government and finance neither understand this distinction nor its policy implications, at least the way the MMT presents it as a development of functional finance (Abba Lerner), and stock-flow consistency (Wynne Godley). There is a body of literature elaborating this.

Anyway, welcome aboard. Hopefully, you will acquaint yourself with what the debate is here and join it, instead of dissing the view being put forward here without understanding it while summarily declaring your point of view to be obviously correct. That would get you a troll rating if there were one to give.

Hi Bill/Scott,

It is a bit shocking for me to have seen Charles Goodhart’s name here: UK economy cries out for credible rescue plan

I thought Goodhart was good. What happened to him ? Any comments ?

Dear Ramanan

Charles is part of the problem.

best wishes

bill

Hello, new here and just trying to wrap my head around all this stuff. Couple questions about this model:

1) Why keep taxes at steady at 600 cards while trying to lower the “national debt”? Aren’t neo-liberals always arguing for lower taxes in addition to lower government spending?

2) isn’t the whole conservative/neo-liberal argument that the “kids” should not be looking for the government to provide most or even any of the goods/services that the 600 cards provides–i.e., to “eat and live in the house”? Wouldn’t they say that the kids could/should be supplying/demanding those goods/services from each other, and so would have had no need to earn the government’s cards in the first place? Or, very much fewer of them at the least?

3) While the private sector vis-a-vis the banks can’t create net assets in the aggregate over time, can’t there be a continuing outstanding balance of new loans (money) created and in circulation relative to older/existing loans due? If that is true, couldn’t the private sector then use come of that excess $$$ to pay the small amount in taxes that would be required in a system with a tiny bare-bones conservative dream-government, even though it would keep the economy as a whole on a demand-for-private-credit/loans treadmill? Seems like that’s the situation they envision.

Any responses/answers/insights much appreciated! Thanks

Welcome, Kent. This is just a model to illustrate how the monetary system operates in terms of some basic principles. It is not mean to be either comprehensive or prescriptive. It’s an introduction to MMT (modern monetary theory), the system in place in much of the world since August 15, 1971, when Nixon shut the gold window. Then the previous convertible fixed rate currency regime was replaced with the current non-convertible flexible rate regime. Many people seem to have missed this transition and are acting like it never happened.

First read A simple business card economy, then this and then the next in the series, Some neighbours arrive.

You may wish to look at Stock-flow consistent macro models, too.

You can also peruse the whole site at Complete billy blog on one page!

Hi Tom,

Thanks for the response. I’ve been trying to learn about all this stuff for the last couple years. It started with learning about fraction reserve lending. The catalyst was reading Ellen Brown’s “Web of Debt” book, Mike Whitney’s and Marshal Auerbach’s posts on Counterpunch, info on the Fed, etc. Anyway, I sent BIll an email but I guess the biggest problem I have trying to grasp the story has nothing to do with the accounting he describes. It makes sense and I get it. The issues I have a hard time with are the underlying assumptions to begin with.

It can probably be best summed up as: in the Barnaby story above, the government pays all the kids’ (private sector) wages to work at “household tasks”. In return, they get to “live and eat in the house”. A whole string of questions arise from that….

1) If the kids represent the entire private sector as presented in the vertical graphic at the top of the page, then isn’t a system where the gov’t pays all wages and determines the tasks to earn those wages describing a completely centralized, gov’t directed economy…i.e., communism, or something very like it?