I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In and Counter-Conference

In Washington D.C. next Wednesday (April 28, 2010) there will be two separate events where the focus will be on fiscal sustainability. The first event sponsored by a billionaire former Wall Street mogul under the aegis of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation (PGPF) promises to bring the Top leaders to Washington. It will feature a big cast well-known US entities (former central bank bosses; former treasury officials and more). It will be well-publicised and a glossy affair – full of self-importance. It will categorically fail to address any meaningful notion of fiscal sustainability. Instead it will be rehearse a mish-mash of neo-liberal and religious-moral constructions dressed up as economic reasoning. It will provide a disservice to the citizens of the US and beyond. The other event will be smaller and run on a shoe-string. The grass roots The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In and Counter-Conference is open to all and will actually involve researchers who understand how the monetary system operates. Like all grass roots movements it requires support. I hope you can provide support commensurate with your circumstances.

The Press release accompanying the Peterson event says that the meeting:

… will convene a broad range of senior officials, policy-makers, elected leaders, and experts at the first-ever “2010 Fiscal Summit: America’s Crisis and A Way Forward” to launch a national bipartisan dialogue on America’s fiscal challenges. The Fiscal Summit will bring together hundreds of stakeholders from across the political spectrum with diverse ideas on how to address critical fiscal issues while continuing to meet the priorities of the American people.

The appeal to diversity is a farce. If you go through the list of participants listed as speakers and identify each name with their public statements over the years and their published output you will soon realise that the diversity involves degrees of deficit terrorism.

When you explore the PGPF issues page you read that their conceptualisation of fiscal sustainability is about a fear of the US federal government “running sizeable deficits” which will continue into the future and the “mounting debt” will “put our nation on an unsustainable path”. They claim that this situation (on-going deficits):

… is the so called “structural deficit”. Absent meaningful entitlement reforms and spending constraints, future tax burdens will have to more than double for the country to get by. Budget controls, program evaluation, spending constraints, and tax reform must be implemented to free up resources to address new priorities and meet new needs. With trade deficits now at twice the previous record levels, and with our low national and personal savings rates, America also has become dangerously dependent on foreign capital.

They consider the solution to this problem to be “deceptively simple: we should pay for current spending and programs with current taxes, not debt. That would avoid passing on the bill to future taxpayers. Each generation must have the flexibility to set their own priorities according to the opportunities and needs of their time”.

Once you read statements like that you realise that the PGPF has no idea of what fiscal sustainability is when applied to a nation that issues its own currency and floats it on foreign exchange markets.

You can gauge how far right the public debate has moved in the last decades by the fact that the term “structural deficit” is now being seen as something bad. I have written about this concept previously.

It is amazing that a simple concept is now so demonised.

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

It might be thought that if the budget is in surplus that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending). It also might be thought that a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa.

But a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the budget balance reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers. Please read my blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – for more discussion on this point.

To provide a cyclically-neutral measure of the fiscal balance some benchmark is required. The Full Employment or High Employment Budget concept was developed to provide this measure of the discretionary fiscal position. More recently, this concept has become known as the Structural Balance.

As I have noted previously, the change in nomenclature is not insignificant because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation. So the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) became the mainstream definition of full employment even though it might mean the unemployment rate was around 5, 6, 8 per cent or even higher.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

While the measurement issues are another matter (that is, how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy) the modern notion of the structural balance utilises various dodgy NAIRU concepts in the measurement process. This always means that the estimates of the discretionary fiscal position area always biased upwards (to be more expansionary than they actually are) and so there is always contractionary bias in fiscal policy.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

Please read these blogs for further information: Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers and Structural deficits – the great con job!.

The other important consideration is that the budget balance does not stand in glorious isolation from other sectoral balances as I have explained often.

Please read my blogs – Stock-flow consistent macro models – Barnaby, better to walk before we run – Norway and sectoral balances – The OECD is at it again! – for more discussion on the sectoral balances.

The three sectoral balances that are derived from the National Accounts are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

If we added (I – S) + (X – M) we get the non-government sector balance. The rule is that a government deficit (surplus) exactly equals ($-for-$) the non-government surplus (deficit).

So what does this mean for the characterisation of a positive structural deficit as being unsustainable? Well it must mean that the PGPF thinks a permanent non-government deficit must be sustainable.

A permanent non-government deficit means that the sum of the external account and the private domestic balance would be negative. If you look at how the balances are constructed then you will realise that where a nation runs an external deficit then for the non-government balance to be negative, the private domestic sector must also be running deficits (that is, spending more than they earn).

Most countries currently run external deficits. This means that if the government sector is in surplus the private domestic sector has to be in deficit.

That means a state of increasing private domestic indebtedness which is clearly unsustainable. This behavioural pattern has defined the last period and has led the world into the crisis.

These private domestic deficits can help maintain spending for a time but the increasing indebtedness ultimately unwinds and households and firms (whoever is carrying the debt) start to reduce their spending growth to try to manage the debt exposure. The consequence is a widening spending gap which pushes the economy into recession and, ultimately, pushes the budget into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

The typical situation is that the private domestic sector seeks to save overall. If a nation is running an external deficit, and the private domestic sector desires to save overall, then the government sector has to run structural deficits if GDP growth is not to be impaired and the nation lapse into recession.

It is obvious that if the nation runs an external surplus then depending on the relative magnitudes of the external balance and private domestic balance, the government could run a public surplus while maintaining strong economic growth. That is the situation for Norway as an example.

In this case an increasing desire to save by the private domestic sector in the face of fiscal drag coming from the budget surplus can be offset by a rising external surplus with growth unimpaired. So the decline in domestic spending is compensated for by a rise in net export income.

That would be a sustainable situation although the nation would be losing materially via the external surpluses and thus constraining its material standard of living below what otherwise might be the case should it be able to enjoy external deficits.

So in just focusing on the budget position and ignoring the other relationships that are interlinked to it via the income generating process, the likes of the PGPF misrepresent the debate and draw erroneous conclusions.

If you reflect back on their statement of fiscal sustainability you will see how confused it is when dealing with the three sectors. They want to reduce the external deficit and increase the private domestic surplus while moving the structural deficit into surplus. Unless they could achieve a fundamental transformation of the US economy – turning it into a net exporter of significant scale – their ambitions are impossible to achieve.

That impossibility should be exposed in the public debate.

Further, the notion that “America … has become dangerously dependent on foreign capital” clearly does not relate to the public balance at all. The US government is sovereign in its own currency and can spend what it likes in US dollars. No foreign capital is required.

This concept is also backwards when applied to the trade flows. The foreigners who wish to accumulate financial assets denominated in US dollars are, are in fact, dependent on the American purchases of imported goods and services not the other way around. The only reason that the foreigners would want to net ship more real resources to the US than the US sends back on ships is to accumulate US dollar-denominated financial assets. The US consumers and firms are “financing” that foreign desire.

So if these sorts of misperceptions are going to be central at the PGPF fiscal sustainability meeting next week in Washington D.C. you can conclude that nothing meaningful will emerge. They will have a plethora of high profile guests including a former President but not one word will be worth listening to.

The problem though is that the PGPF has significant resources which enables them to effectively prosecute their ideological position with impunity. By deploying their huge resource base in staging these events they can effectively “crowd out” democratic debate in the US and elsewhere.

Their marketing efforts are also well-resourced. As an example of how they are misleading the public you only have to examine their glossy State of the Union’s Finances – A citizens’ guide 2009.

It opens with a letter to “Our Fellow Americans” signed by Peter G. Peterson and David Walker (the CEO of the PGPF and former United States Comptroller General). Walker is a vociferous deficit terrorist.

In that letter you read reference to the crisis in the mortgage-sub-prime markets and then they say:

We cannot afford to let the same thing happen with our nation’s finances …

Well the two situations are not comparable. The former crisis was about private sector insolvency – debt holders not being able to pay their debts. These debt holders were households and firms who use the currency issued by the US government. As users of the currency they are always financial constrained and have to fund their spending. If they reach a position where their nominal income can no longer service their nominal contractual obligations then they are forced to default. That was the basis of the financial crisis.

But the US government is the currency issuer. As a sovereign government it is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of that currency. It faces no solvency risk at all. It will always be able to service its debt obligations and repay the principle upon maturity.

There is simply no valid analogy that can be drawn between the private sector and the government sector budgets and their respective financial obligations.

Then you read on:

The facts are clear and compelling – the federal government’s financial condition is worse than advertised, and we are on an imprudent, irresponsible and immoral path. Washington policy makers are mortgaging the future of our country, children and grandchildren while, at the same time, reducing the level of investments in their future. We are also becoming increasing reliant on foreign lenders to finance our nations’ debt.

There are no facts presented in that statement. The only compelling fact that emerges from that diatribe is that the two signatories fail to understand (or don’t want to tell the truth about) how the monetary system operates and are on a moral crusade (disguised as an economic case).

Not the words – an “immoral path”. When you question a deficit terrorist and force them to abandon their faulty economic logic (because it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny) they ultimately resort to these religious type statements which give their true agenda away.

They simply have some puritanical view that government spending is immoral unless of course it is bailing out their failed enterprises or otherwise smoothing the way for them to make more wealth at the expense of everyone else.

Once they play the morality card – they have lost all economic credibility.

Further on in the Citizen’s Guide, after they present a graph that alleges that the US federal debt will reach 350 per cent of GDP by 2050 (noting it peaked at 122 per cent during WWII and is typically below 50 per cent), they say:

Arguably, we are already getting a taste of what that future will be like. Since the middle of 2007, problems in the U.S. housing sector have illustrated what happens when lenders lose confidence in borrowers. The economic difficulties of smaller countries like Iceland and Hungary show what happens when no one wants to lend a nation money. If our ability to manage our nation’s fiscal affairs is called into question, we are likely to face even more severe economic challenges, including sharply higher interest rates, further downward pressure on the dollar, higher prices for oil, food and other necessities, and greater unemployment.

Once again you see them blurring the household-government distinction and using the household budget analogy to make inferences about the viability of public budgets.

I just repeat the US government doesn’t require anyone to lend them money! Ultimately, if the US government failed to place any of its debt into the bond markets then the central bank could buy it all. Preferably, they would question the need to issue debt at all. But there is no question that the US government will ever run out of US dollars. They have an infinite supply of them. No foreign entity supplies US dollars to the US government.

The Citizen’s Guide then moves into the demographic change debate:

Known demographic trends and skyrocketing health care costs are the crux of the problem. Most of the 77 million post-World War II baby boomers (representing one fourth of the U.S. population) are still working, but some are beginning to retire. As boomers retire, federal spending for Social Security and especially Medicare, given rapidly rising health care costs, will grow dramatically. As they do, younger workers – our children and grandchildren – will ultimately have to foot the bills.

As populations age, it is likely that the real resource usage will shift from provision of baby health centres to aged care units. Productivity growth will make that transition more efficient. Social programs encouraging better diets and fitness regimes will also reduce the need for health care somewhat.

But these shifts in resource allocation are hardly new and will be mediated via the political process.

As I have indicated often – these questions are not of a financial nature. The US government will always be able to buy health care resources for its citizens should there be products and services available. They will always be able to pay monthly pensions to an increasing number of recipients.

Both transactions involve the stroke of a keyboard key which transfers funds from one account (government) to another account (non-government). There is no financial constraint involved.

So the only questions are the real ones – Will there be enough real resources available? How will they be distributed? These questions have nothing to do with fiscal solvency.

I could continue to find terminal faults with every paragraph in the Citizen’s Guide. It is a deplorable document designed to mislead and advance an agenda that is different to that stated.

The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In and Counter-Conference

The other fiscal sustainability event in Washington D.C. next Wednesday (April 28, 2010) that is being staged is The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In and Counter-Conference. The details of venues and other relevant arrangements are available at the home page and will be augmented as further information comes to hand.

This is a grass roots activity – evolving out of the efforts of committed citizens who realise that the PGPF elitist vision does not constitute a valid representation of what the future challenges facing our societies will be. They realise that something has to be done. But like most citizens they needed help from researchers who do understand what is going on.

Bringing the energy of the grass roots activists and the know-how of the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents together will increase the scope of both groups. It is only a small step but as Australian singer Paul Kelly told us From little things big things grow

The song is about how resistance and union builds momentum which eventually becomes unstoppable.

So the alternative fiscal sustainability event will be the first grass roots effort to promote MMT. The day has been chosen to rival the sham PGPF conference exploring the same topic.

If you are near to Washington DC and have the means it would be great to meet you next week.

You will also note that I have included a fund raising widget on my right side-bar. Any help for the organisers will be very appreciated. Just click the image and open your bank accounts! The fund-raising home page is HERE

At present they really need some financial support. It is a shoe-string, community-driven event being organised by committed volunteers who are motivated by the fact that they care and realise something is wrong with the dominance of conservative, free-market think tanks like the PGPF in the public debate.

What I hope comes out of the Teach-In is a range of educational materials that can be spread via the Internet to offset some of the lies that the PGPF propaganda machine puts out effortlessly each day.

How to turn a demographic group off

The Australian federal opposition leader Tony Abbott has had what has been described as a “Sarah Palin” moment today when he hinted that the conservatives would propose scrapping the unemployment benefit for under-30s to force them to move to remote areas in the nation to search for work (Source).

Apparently mining industry leaders have proposed that no income support be provided for unemployed people up to the age of 30 because the desperation would then force them to travel to the other side of the continent to work.

The Opposition leader was quoted on ABC news as saying:

There has got to be a system that encourages people to take up work where that work is available.

Last time I looked that system was the labour market. An employer makes a job offer at a wage attractive enough to entice workers (which should include significant disamenity allowances for dangerous jobs thousands of kms from civilisation – as in the mining sector of Australia) and the workers react.

I know the mainstream argument is that the presence of an income support payment provides a disincentive for workers to accept wage offers. But the evidence is also clear from the research literature that the fundamental constraint on people’s labour supply is a lack of jobs.

It also turns out that the economy is failing to provide enough work overall for our youth.

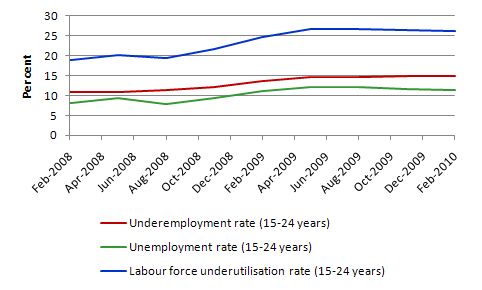

The following graph shows the underemployment rate (%) (red line); the unemployment rate (%) (green line) and the total labour underutilisation rate (%) (blue line) for 15-24 year olds in Australia, the latter being the sum of the other two measures of labour wastage. The data shown is from February 2008, which was the low-point unemployment rate in the last cycle to February 2010. The data is available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

So over 25 per cent of 15-24 year olds are without work or without enough work. That is, Australia is choosing to waste more than a 1/4 of its youth labour resources. And the only thing that the opposition leader can come up with is to punish this group even further by cutting the pittance they receive in income support to “save the taxpayer funds”. Ridiculous.

The mining industry will never offer enough jobs to absorb all the under-30s that are currently without work or without enough work. If there are un-filled vacancies in that industry they will be very small relative to the numbers without enough work.

You do not introduce policy that discriminates against a broad age-group, which is already the most disadvantaged in terms of lack of policy support, to solve a minor problem.

Further, the policy would be highly discriminatory against lower income people who are unable to enjoy the support of parents etc.

What Tony Abbott should be advocating is a Job Guarantee to make sure everyone has work at a minimum wage as a national benchmark. Then industry has to better those conditions to attract labour.

One imagines that the political damage to the opposition will be enormous. The older segments of the population are typically conservative but the younger voters have shown they have rejected conservative values (at the last election). This move will reinforce that anti-market sentiment.

The scary part of the story is that the Prime Minister’s only response was that the:

What we have … from Mr Abbott is once again policy making on the run … I just think it’s time Mr Abbott had some sort of work on these sorts of questions.

You would have expected a Labor Prime Minister to say something like … “in a civilised society we do not force people to starve through lack of income when the economic system fails to produce enough jobs”. And “given that we are politically gutless and have failed to introduce a Job Guarantee to ensure everyone who wants a job can work then the least thing that government should be doing is ensuring those people we have forced into unemployment have some income to live on.”

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill,

Thanks again, I hope to make it to DC and learn something from the Teach-in.

My suggestion would be to include some mano-a-mano to the Peterson Groups five major arguments.

Actually, a lot of that.

I want to raise another point here, perhaps nit-picking in the $Trillions to one of the basic tenets of chartalist thinking.

This is not an argument, rather something I think needs addressing.

It’s partly that “self-imposed constraint” thing – the actual lack of the government being the monopoly-issuer of currency in our sovereign, non-pegged exchanging world.

The first part may be simple in that it is not the government that is issuing the currency here in the US. Our self-imposed constraint is the creation through the law of the land of the supposedly-PRIVATE, supposedly-monopoly currency issuer – that of the (non)Federal Reserve Bankers.

Simple enough – remove the self-imposed restraint and make the Fed part of the government where we the sovereigns take over, and in your generally presented view, control the money system through issuance of monetary reserves (hot money) to manage the currency. Simple. Repeal or amend the Fed Act.

But what about the other $Trillions? What about the powers of the Shadow-Investment bankers to create $USD-denominated thingies, or ‘vehicles’, that create $-denominated financial debt obligations that serve the exact same function as currency – so to me they are currency. It was well stated defensively by almost every Fed official at the Minsky Conference last week that MOST of the money created during the entire last generation was NOT created by the (non) Federal Reserve commercial banking system.

I guess my point is that the self-imposed restraints go further than bringing the central-banking function back under the government. It must include a broad prohibition against the ability of any private “leveraging” up of base money with financialized debts.

My solution to the present inevitable debt-money deflation cycle is the same as proposed by Dr. Fisher – a move to real, honest full-reserve banking. What do we do about the money-creation power of the shadow bankers?

Thanks, Bill.

This construction “pass the bill on to our descendants” seems incoherent to me. If we could actually “pass the bill on to our descendants” why can’t our descendants “pass the bill on” to their descendants, and so on into the infinite future? Problem solved!

Of course, we can easily create a new burden for future generations by using up currently available resources so that they will no longer exist, thus making our descendants all poorer. We can poison our planet leaving nothing but a devastated planetary surface for our children to survive on, if we like. But that is not “passing a bill” in any financial or economic sense, and I just wish economists, who should know better, would stop using such incoherent phraseology.

Financially speaking it is not possible to pass a bill on to our descendants because, for everyone who owes there is someone who is owed, and so the whole society owes nothing. You can’t pass on something that doesn’t exist last I heard.

You mention that a government has to be in surplus for the private sector to be in debt.

However here in the UK we have a private sector that is heavily indebted, a public sector that is heavily indebted and an addiction to chinese import. How does that work with your theories?

joebhed, here’s my take.

1. The Fed as the CB of the US is a de facto government agency and is not privately owned. I agree that the so-called public/private status of the FRS is confusing, so it should be changed to reflect operational reality. CB operations should be clearly separated from routine settlement operations, for example. This requires revising the FRA of 1913. The CB is (supposedly) independent of political influence, not privately owned. The Fed chair and majority of the member of the Fed boardFed board are political appointees. Chairman Bernanke was a university prof, for example. (I’m not lobbying for Bernanke here or claiming that he is not intellectually captured.)

2. Reserves are not used to manage the currency. They are used for settlement and to manage interest rates. Currency issuance is subject to appropriation by the US Congress and presidential approval unless a veto would be overridden. The Treasury disburses the currency by crediting bank accounts, and the Fed supplies the reserves for settlement. There is no financial obligation to the Fed created by Treasury disbursements. The Treasury does not pay interest to the Fed, and the profits of the Fed are turned over to the Treasury. (Is the Fed managed in the interest of the financial sector? I believe so, with the idea that what is good for Wall Street is good for Main Street, and vice versa.)

3. Base money does not get leveraged up, because banks don’t loan against reserves. The reserve requirement is a liquidity provision that banks undertake consequent to making loans. Rather, banks loan against capital. The way to constrain leverage is through the capital requirement, not a reserve requirement.

4. Only the government has the prerogative of issuing currency. Banks can lever their capital up to the limit set by the capital requirement in creating credit money. It is a matter of debate whether the shadow banking system can create credit money. However, they can create instruments “having moneyness” by creating financial obligations. The matter of reform that is somewhat beyond the scope of MMT per se, which, as I understand it, deals with the vertical-horizontal relationship of the government as currency issuer and the banking system as creator of credit money. MMT recognizes that the money supply consists chiefly of credit money and that credit money is created endogenously by credit extension. Government exerts control through financial regulation, e.g., capital requirements, which are solvency provisions that constrain the use of leverage. A number of economists, including MMTer’s, have submitted a reform proposal here.

Dear Neil Wilson

You said:

I didn’t mention that. You are confusing the “private sector” with the non-government sector. The rule is that the if the government sector is in surplus then by national accounting the non-government sector has to be in deficit. The non-government sector is the sum of the private domestic sector and the external sector.

The two deficits you have noted in the UK are accompanied by a third – an external deficit.

best wishes

bill

Neil, government surpluses imply nongovernment deficits. Nongovernment deficits mean that the public has to reduce its lifestyle or borrow to maintain it. Private debt is unsustainable, and this results in the public retrenching, causing nominal aggregate demand to fall. That contracts the economy, and automatic stabilizers kick in as unemployment rises. Tax receipts also decline. The government deficit rises correspondingly. A negative trade balance compounds the nongovernment deficit since it draw funds from the economy. Government has to make up the difference while the private sector is recovering. Imports may fall due to decreased demand and that’s a plus, But the public still has to save to service its accumulated debt and that takes some time. This outcome sounds like what you are describing in the UK. Hang in there and hope that reason prevails and the government deficit spends to stoke nominal aggregate demand instead of tightening to look “fiscally responsible.”

Good point, Ed. It’s not financial obligations this generation is passing forward. It’s real devastation.

Dear Bill and others,

I’ve been reading through some of the entries on this blog seeking to get to grips with MMT. Much of it seems fairly straightforward, but it also raises some questions. Perhaps you can point me in the right direction for finding the answers, or provide a quick explanation.

The key issue for me is the following: You state that government spending is limited only by the volume of goods and services offered for sale. I agree. You seem to imply further that the volume of goods and services offered for sale at any moment in time is equal to the potential output of an economy at full employment. In other words you seem (to me) to assume that state spending resulting from net money creation will instantly bring forth a corresponding increase in output, thus avoiding any inflationary effects.

I find this rather questionable. State spending may create employment at will (paying people to dig holes and fill them up again – or more useful activity) but such schemes rarely increase the output of goods and services offered for sale. If funded by net money creation, they just “pump” money into the economy and stimulate demand, without directly creating a corresponding increase in supply. So the question then is whether, and how fast, this increase in demand will stimulate an increase in output, including through investment, and whether, and how much, it will have an inflationary effect.

On this point, we are back in more mainstream territory, and I am inclined to be pessimistic. Whether or not firms invest and increase production will depend on factors such as confidence, expectations of inflation and the strength of wage demands. There is also the question of the rate at which the volume of goods and services offered for sale can be increased. To the extent that there is an existing build up of inventaries, the rate is fast. Using spare capacity has a greater time lag, and new investment has a greater time lag still.

Therefore, might we not say say while monetary policy should seek to maintain a degree of liquidity to encourage investment, it can otherwise only increase money supply in line with the growth of the economy? Seeking to increase the money supply faster than output can be increased will, according to this viewpoint, only lead to inflation that is effectively a tax on the holding of cash and fixed return financial assets. If this is true, then government spending would indeed be limited by taxation. It would specifically be limited to the equivalent of tax revenue (including the “inflation tax”) + public borrowing + the % growth in money supply allowed by economic growth.

It would be nice to think that I have reached this conclusion by missing something fundamental, so I look forward to your response.

Great post, and best wishes for your teach-in. It is ironic with the demographic fears that the government/economy isn’t putting young people to work more effectively. These are exactly the people who we will need to support us in our dotage. So they had better get cracking!

Also, you mention “debt exposure” for private parties. Combine those words with the word “trillions”, and its ability to inspire fear is understandable. The MMT community should work to come up with a better name for “national debt” which reflects its true character and has less stigma. Perhaps a contest would be helpful. Something like redistribution account, or government sponsored savings, or net savings position, or financier safety account. etc..

Neil Wilson, this may not be complete but I am going to with …

“surplus” of the domestic rich plus “surplus” of the foreign rich is near “deficit” of the domestic lower and middle class plus “deficit” of the domestic gov’t.

Off-topic and for JKH or anyone else, I found this over at baselinescenario.com (a Comment):

“Another reason for bank participation is Basel II, which assigns lower capital requirements to this drek (refering to CDO’s) than to actual loans. Why would a bank make an actual loan when it can place a bet at far lower costs and book a nice profit, producing a nice bonus, at inception.”

Is that correct, and if so, why?

Fed up: Why would a bank make an actual loan when it can place a bet at far lower costs and book a nice profit, producing a nice bonus, at inception.”

Answer: The incentive is to take undue risk in the knowledge that no one is going to your bonus away even if the deal blows up, and government is covering possible losses anyway. It’s heads I win big; tails and I keep my bonus and I get bailed out. Some call it moral hazard. When CEO’s run their company this way, William K. Black calls it control fraud.

Tim Bending, companies make investment decisions based on risk/return. If a company decides it can make enough profit to yield a reasonable return on an investment, it will be inclined to invest if risk is commensurate. The two big factors involved in making a profit are demand for the product and cost relative to price. One of the largest costs is labor. So companies like an environment in which demand is growing and there is little wage pressure. MMT is about creating and maintaining that environment through fiscal policy that delivers full capacity utilization, full employment, and price stability.

Burk: “The MMT community should work to come up with a better name for “national debt” which reflects its true character and has less stigma. Perhaps a contest would be helpful. Something like redistribution account, or government sponsored savings, or net savings position, or financier safety account. etc..”

National Kitty

National Purse

National Piggy Bank

National Cornucopia

National Rainbow Trust Fund

National Deep Pockets

National Reserve Account

National Money Bag

Rosebud

.Once they play the morality card – they have lost all economic credibility.

it is interesting to view this from the vantage of ideological norms. The idol is debt, which is a “sacred” obligation to repay, so households that default are immoral if they do so, but business that do so are only exercising a “strategic option.” Similarly, government deficits are “necessary evils” in a GOP administration, but just plain evil in a Democratic one. This is a shifting norm, it seems, and an idol with feet of clay.

Dear Joebhed at 10.20pm

I would eliminate much of the shadow-banking sector and force it back into the regulated banking sector. In doing so I would eliminate much of the speculative financial markets starting with OTC derivatives. That would make the “shadow” sector fairly small.

This would redirect investment back into real capacity building and/or lower risk financial assets.

I hope to see you in Washington next week.

best wishes

bill

Dear Ed Seedhouse at 3.27am

Exactly. We do not ask our kids to send back all the real resources we have used up! The demographic problem is always about real resources and has nothing to do with what the government can or cannot afford.

best wishes

bill

Dear Tim at 8.13am

Thanks for your input.

You say:

First, why be so unimaginative about the capacity of public employment programs. In South Africa, a program I provided input into builds productive capacity. Our research in Australia has identified massive unmet community and environmental need that could be addressed with a Job Guarantee. During the Great Depression, major infrastructure projects were constructed in the US and Australia (and elsewhere) that still deliver returns today. The Great Ocean Road in Victoria is a multi-million dollar tourist resource for that state and was built as a “make work” scheme.

Your statement that “such schemes rarely increase the output of goods and services offered for sale” is therefore without firm empirical foundation.

Second, they certainly stimulate aggregate demand (by whatever is the difference between the wage paid and the unemployment benefit times the propensity to consume). But that is exactly the point.

Your comment “without directly creating a corresponding increase in supply” then sits oddly. In these circumstances, there is a large underutilised capacity on the supply side. What model of a firm seeking to retain market share do you have that says they will not utilise that capacity to meet the new orders flowing through the door?

All the empirical evidence shows that firms are quantity adjusters when they have excess capacity. That is, they will increase production when there is an increase in nominal demand if they can. So in times of recession, it is highly unlikely that inflationary forces will reveal themselves if the former was a demand phenomenon.

You then think:

I don’t see this as being “mainstream territory” exclusively and I don’t see that this follows from the first point. If there are inventories in excess, firms will sell them. No inflationary effect. Then the stock-cycle kicks in and they start producing again taking up capacity slack. They can bring on another shift fairly quickly in fact.

Then new investment follows later as the expectations of the durability of the recovery are formed. Nothing mainstream about this.

You then say:

Monetary policy (setting interest rates) cannot influence the growth in what you call the money supply. The latter is a function of the banks creating deposits via loans. It depends on how optimistic borrowers are. The reasoning in this paragraph is all mainstream quantity theory with overtones of the money multiplier. None of it applies to a fiat monetary system.

The growth in money aggregates tells you nothing definite about the relationship between nominal demand growth and the growth of real capacity in the economy. But the essential point is that fiscal policy can stimulate nominal demand and increase real output with the up-side risk being inflation if it overheats the economy. There is nothing in that statement though that should deter a robust fiscal strategy aimed at achieving full employment.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

Thanks for the response,

First of all, I’m all for a robust fiscal strategy aimed at achieving full employment.

However, I still feel your advocated policy approach (apparently demand management through money creation) relies on a very high degree of optimism about inflation, so that inflation can be effectively disregarded as a problem.

On public spending not increasing the output of goods and services for sale: I’m perfectly aware that there is lots of good opportunities for public investment. The question is whether such public investment leads to the anything being offered for sale. State funding of investment in a nationalised industry otherwise run on a commercial basis (i.e. selling things) increases output. Building a really useful road that people can use for free does not. Its not about whether the investment is worthwhile, but about whether the net increase in money is met by a net increase in purchasing opportunities.

Given that fact, we are back to the question of whether the increase in demand from net money creation will lead to inflation or output growth. Here the important question is: how fast can supply respond? As I stated, excess inventories and spare capacity mean a relatively fast response, investing in new capacity, however, takes time. My point is that a degree of liquidity will tend to promote growth (but with a trade off on the inflation side), but that otherwise the rate at which money can be created (and hence the rate of government spending) is limited by the rate of economic growth.

This is a very different picture than what MMT seems to suggest. It says that governments can’t spend at will but may be severely constrained by the risk of accelerating inflation. It puts the focus on how output growth can be promoted. You even seem to agree with this when you say:

“the essential point is that fiscal policy can stimulate nominal demand and increase real output with the up-side risk being inflation if it overheats the economy”

You seem to regard “overheating” as something exceptional and not really to be worried about. But your radical fiscal stance would also be something exceptional from a historical perspective. I fear that an attempt to implement the MMT approach would quickly find that it was funding spending by taxing holders of cash and financial assets (inflation).

You say that this reasoning: “is all mainstream quantity theory with overtones of the money multiplier”. This is really just name-calling. I have not be able to discover from what I have read why this reasoning should not apply to a fiat money system, but I am willing to be enlightened!

Thanks again,

Tim

It is a pity that after a mere two weeks from the deaths of 29 miners in West Virginia at the hands of people who have zero respect for workers, your Opposition leader has suggested a plan to literally FORCE young workers underground at wages insufficient to attract them economically to the high risks and toil of that job. Perhaps Tony Abbott also wishes a return to Australia’s past as a prison colony? That too was an effective solution to a problem of labor shortage, and no doubt fashioning these mines into prisons could also save the mine owners lots of money.

Perhaps it might be instructive then to begin referring to Tony Abbort in your press as “Australia’s Don Blankenship”?

Tim,

I get very much surprised that it seems so weird to many people (american?) that government in no way can create economic goods and expand capacity within its job guarantee offer. One could argue that there was no freedom of choice in the USSR at the same time absolutely everybody had a job. Being without job was equivalent to being a criminal which was often a personal choice rather than any from of government-led prosecution (though it was the case as well). The point is that with the whole country being effectively on a job guarantee scheme it was still possible to build a global super power in a very limited period of time with virtually no external help. And not just in the nuclear or military sense but also in scientific, cultural, sport, ethical and so on. One can condemn many facts about the Soviet system but so is with the USA. One can also praise many other facts about USSR. And again so is about USA.

Dear Tim

My so-called radical fiscal stance was actually the mainstream operation from about 1939 to at least the mid-1970s – more or less continuous budget deficits in most countries and near continuous full employment.

You say:

I have written many blogs about this – I urge you to read them.

best wishes

bill

Dear Sergei at 22.11,

Indeed, in a command economy, the issue I raised wouldn’t be a problem because the job guarantee would be paying people in state industries to produce something that would get sold. The problem in a market economy is that not that the state cannot employ people to do useful work, but that if the state uses net money creation to employ people whose output is not purchased by others, but is free to users, as in pretty much all such direct job creation schemes, then there is a big question about inflation that has to be answered. In terms of the moneatary system, it should make no difference whether you pay people to work in this way, or just put a cheque in the post: demand is increased, but supply not automatically so.

Hi Tim

“The problem in a market economy is that not that the state cannot employ people to do useful work, but that if the state uses net money creation to employ people whose output is not purchased by others, but is free to users.”

Not always the case, the government can always put a toll on the new road, not to fund anything but maybe to drain the excess liquidity arising from fuel savings due to decreased travel time.

Such savings in Australia usually go into buying the next investment property (humour intended).

If there is an inflation risk the government can always use fiscal policy(like taxation) to adjust market behaviour and reduce such risks. From what I understand of MMT ,it calls for proactive intervention by government (using fiscal policy) to dampen such inflationary effects.

Dear Bill at 22.32,

You say:

“My so-called radical fiscal stance was actually the mainstream operation from about 1939 to at least the mid-1970s – more or less continuous budget deficits in most countries and near continuous full employment.”

If all you are saying is that governments with fiat money can spend a bit more than their tax and borrowing intake, but only at the rate that their economies are able to respond to increasing demand with increasing output, and don’t “overheat”; and that they are never technically insolvent from debts denominated in their own currency, because they can always inflate their way out of trouble, then why the fanfare? This is surely not controversial.

However, you seem to be suggesting something much more radical, something only possible in the post-1971 world. I’m left with the impression that while the conceptual framework used by Wray and yourself may be useful, the policy implications are in fact not so different than from what other post-keynesians like James Galbraith are saying. It all very well stating that tax and borrowing don’t fund anything in a fiat system, but if governments are nonetheless constrained to raise, through tax and borrowing, the equivalent of nearly all of their spending, then the difference is merely one of semantics.

“I have written many blogs about this – I urge you to read them.”

Well, I did read a number. But I also understand that its a pain to have to restate your arguments in comment threads all the time. I had hoped you might be able to point me to a particular explaination elsewhere.

I remain open to the possibility that there is something critical I haven’t understood about MMT, yet also skeptical.

Thanks for your responses and all the best,

Tim

Tim, I can’t see much of a gap between Bill and James Galbraith.

see http://www.thenation.com/doc/20100322/galbraith

Good luck with your quest.

Tim,

you seem to value guaranteed (but only on the upside but not on the downside) stability of prices and worthlessness of pieces of paper and electronic records much more than ruined lives of millions of people. That is a political judgement and not economic. Political judgement can also prosecute freedom of speech, choice, Jews, non-whites, favor smoking and drinking in public places and so on but it has no grounds in economics. So you have full right to be skeptical about MMT but it comes from your personal values and judgement and your personal disbelief that even in a market-driven economy government can not productively employ people without competing with market itself

“My so-called radical fiscal stance was actually the mainstream operation from about 1939 to at least the mid-1970s – more or less continuous budget deficits in most countries and near continuous full employment.”

Things were pretty good under the gold standard. Is compatible with MMT, after all, against everything I thought I had learned from it?

I’m willing to accept whatever epithet deemed appropriate for my ignorance, but in exchange for an answer. 😉

Happy to announce that I will be attending the MMT conference in DC.

Cheers

Tim: It all very well stating that tax and borrowing don’t fund anything in a fiat system, but if governments are nonetheless constrained to raise, through tax and borrowing, the equivalent of nearly all of their spending, then the difference is merely one of semantics.

As Bill has amply pointed out in the past, in the end it comes down to distribution of available real resources and this is a political decision under any form of economic system other than laissez-faire capitalism, which no longer exists in a pure form – likely because it toward monopoly and doesn’t cut it in a democracy where workers have the vote.

What MMT does is unhook government spending from payment by showing that the monetary sovereign is not financially constrained, so equivalent offset of spending and revenue/debt is not required. This makes appropriation one policy decision and adjusting net financial assets by withdrawing funds through taxation another. It’s an approach that is more rational because it accord with operational reality rather than myth.

But political decisions do still have to made about distribution, incentives and the like, and different political factions will disagree over these issues. The matter will be decided periodically by eligible voters, where it should be decided in a democracy.

Bx12 Things were pretty good under the gold standard. Is compatible with MMT, after all, against everything I thought I had learned from it?

The reason that FDR dropped gold convertibility for the private sector and Nixon dropped it for international settlement was that it was restricting the ability to respond to domestic economic crisis. If you think that thing looked pretty good under depression or deep recession, I guess that wouldn’t be an issue for you. Fiat currencies provide much more flexibility in managing economies.

This is why I suspect that the EMU is eventually going to wake up and realize that the present structure is based on a flawed idea. Even though the EMU is not based on the gold standard, it involves otherwise sovereign governments forfeiting monetary sovereignty. This is the real issue.

Tom Hickey: “As Bill has amply pointed out in the past, in the end it comes down to distribution of available real resources…”

So if a country is very poor in real resources like water, oil, minerals etc, it would mean that such country will have to apply MMT principals in its economy and put as a priority achieving external surpluses so it could collect enough foreign currency and be able to purchase all the necessary resources it lacks itself?

rvm So if a country is very poor in real resources like water, oil, minerals etc, it would mean that such country will have to apply MMT principals in its economy and put as a priority achieving external surpluses so it could collect enough foreign currency and be able to purchase all the necessary resources it lacks itself?

Unless it is the US, which is the monopoly provider of the world’s reserve currency, if a country doesn’t have the wherewithal to purchase something it has to either get the financial resources to do so or borrow them. If its own currency is weak or it is not monetarily sovereign, that is a problem. That happens irrespective of MMT. On a gold standard, countries had to get gold, either through purchase or trade surplus. Now that gold is no longer used for international settlement and dollars are, countries have to get dollars. They cannot print them. Only the US can. MMT has nothing to do with this situation.

MMT deals with sectoral balances and shows what the accounting show. That’s the operational reality that a country has to deal with. Each country has its own strengths and weaknesses it has to take into account. Some countries have to trade their resources for resources they need if they don’t have them. Australia and the petro producers are in this boat. If their natural resources would run low, they would have to find something else. Other countries have to export products and services instead. Japan and most of Europe is in this boat, since they need oil they don’t have. Alternative energy technology is already changing that somewhat.

What MMT also shows is the opportunities for international cooperation. As long as monetarily sovereign countries act as through they are financially constrained, the opportunities appear to be narrower than they actually are. The reality is that a lot of the issues are just numbers.

For example, during the GFC, the US came up with almost a trillion $ to stabilize Europe. No problem when one realizes it is just “paper” and guarantees of paper, i.e., just numbers on a spreadsheet. Most of this is only accounting – no real exchange is involved. The real challenge is distributing real global resources for the survival and progress of the human race instead of pursuing nationalistic goals and self-serving interests. The problem is not with the figures in accounts, it is with the real resources that these figures represent a claim on. That’s where the rubber hits the road.

As Bucky Fuller pointed out decades ago, from an engineering viewpoint the technology and the resources exist to make the world a utopia if properly managed. The problem is in minds and hearts, not in actual capacity.

So the US government can buy all available products and services around the globe. What makes USD so special that it turns all the countries into one world private sector and the US government into one world government?

That’s what being the world’s sole superpower entails. Don’t worry, it won’t last forever. It’s an artifact of WWII.

With this power the US has the opportunity either to create empire, or make the world a more prosperous and harmonious place for all. These are pretty much exclusive, although many in the US would like to think that they are not.

US better chose the latter – history shows that all empires are destine to self-destruction.

Thanks for you reply, Tom.

“The reason that FDR dropped gold convertibility for the private sector and Nixon dropped it for international settlement was that it was restricting the ability to respond to domestic economic crisis. If you think that thing looked pretty good under depression or deep recession, ”

The fact remains that “My so-called radical fiscal stance was actually the mainstream operation from about 1939 to at least the mid-1970s – more or less continuous budget deficits in most countries and near continuous full employment.”. So the question becomes : were these accumulated budget deficits bound to cause havoc under the gold standard?

Unless this question can be answered positively, your general recommendation “Fiat currencies provide much more flexibility in managing economies.” is a bit of an extrapolation. Even the, countries ultimately have the option to switch to the fiat currency system anyway, as they did. The question is : is it preferable under non-crisis circumstances?

As I understand it, unemployment as a buffer stock to keep inflation on target is a child of monetarism, that was engendered shortly after convertibility to gold (let’s say Volcker, 1979), eight years after abandoning convertibility to gold. You can blame the policy theorisers/makers for adhering to an incoherent set of beliefs, but it ‘s a separate matter from that of whether the fiat system might a (worse than gs) built-in unemployment/inflation stability trade off.

About the Euro : I actually don’t agree with Bill’s depiction of Germany as the bad example because they’re setting the bar low for wages. Their relative successes in terms of employment actually give ammunition to the neo-liberal view/slant. You can’t accuse the latter of being “inflation-first” when at the same time reduced wages actually achieve what they’re supposed to : reduced unemployment. Isn’t the philosophy of the job guarantee anyway (minimum wage but you have a job)?

By the way, if the Euro is similar to the gold standard bec. of the horizontal nature of gov spending (I raised that question quite a while ago persistently on this blog and has now become common parlance), that dates back to 1994, not 2002 (introduction of the Euro), and for some countries as far back as 1973. It would be nice to get the facts right, particularly when it’s used to argue in favor of MMT. I have given all the evidence I’m aware of here at Warren Mosler’s site moslereconomics.com/2010/02/15/question-for-mr-mosler-re-us-debt-to-china/#comment-16259

As I once suggested, MMT proponents IMHO are going to have to determine a taxonomy of monetary systems, both structural (gold, fixed-FX etc) and in terms of policies (quantitative easing etc.) by which countries-by-period are classified. A simple table with the more potent examples (Argentina etc.) to begin with might help, so we can begin to see the big picture. By the way I have yet to hear it answered whether or not Argentina was in fiat currency-floating system when its problems began. Is it a dirty secret?

rvm So if a country is very poor in real resources like water, oil, minerals etc, it would mean that such country will have to apply MMT principals in its economy and put as a priority achieving external surpluses so it could collect enough foreign currency and be able to purchase all the necessary resources it lacks itself?

If you’re interested in the history and all the details, read Michael Hudson’s “Superimperialism.” It’s excellent.

“Unless it is the US, which is the monopoly provider of the world’s reserve currency, if a country doesn’t have the wherewithal to purchase something it has to either get the financial resources to do so or borrow them. If its own currency is weak or it is not monetarily sovereign, that is a problem.”

Good point, Tom. I’m not certain that such arguments (valid, in my view) are always treated even-evenhandedly. The impression that I get is that a sovereign monetary system is always given preference, no matter how small the entity (Ireland, Greece, etc.). Others have raised that point too. Is the notion of optimal currency area that irrelevant? Why then? I’m not suggesting the EMU is, but aren’t there blocks within that might be?

I’m not particularly drawn to the “it’s just numbers on a account” line of thought, however. The distinction should be made clear when there is an actual transfer of wealth (as I think is the case when we’re talking of subsidy from one country to another), and when there is only a change in a portfolio’s composition (quantitative easing, albeit in completely different context).

Dear rvm, Henry and others

An application of MMT principles to policy cannot resolve every problem there is. Properly applied MMT principles allow a government to maximise the utilisation of the available domestic real resources. It may increase the availability of resources (for example, high quality education leading to medical discoveries that keep people healthier etc) but in the short-run a real resource constraint is something that policy can do very little about.

For a country with zero resources other than people, then export income has to be earned. If that is impossible then such a country would be at the behest of the rest of the world for generosity. But even then MMT tells us that the government can ensure its own people are achieving their potential (should they want to).

best wishes

bill

Dear Bx12 at 1.13am

Thanks for your comment. I am glad that every comment I make is closely scrutinised – it is a discipline.

Things were sometimes pretty good under the gold standard but the stop-go growth patterns were difficult to manage. External deficit nations continually had to be putting the brakes on to ensure the current account was moderated to avoid putting pressure on the parity. Further, monetary policy was often forced into contractionary mode and some nations experienced entrenched recessions.

Ultimately, the trade balances and the gold implications became too great for the system to remain stable and by the mid 1960s it was unsustainable. It should also be noted that during this period the global financial flows were a shadow of what they have become. The financial flows are such now that a nation would find it impossible to defend its peg should they encounter persistent external deficits.

The point is that the gold standard system did deliver good outcomes for many nations for a time. But it was also when governments were firmly focused on maximising employment subject to the parity constraints. With the exchange rate floating and currencies non-convertible that ambition is eminently easier to accomplish.

A fiat currency system allows the government to implement logically consistent policy and eliminates unnecessary constraints (if the government allows that). It avoids the stop-go dilemmas of the fixed exchange system and doesn’t force external deficit nations to be continually depressing demand to the detriment of domestic output and employment growth. The correct application of MMT principles would allow a government to maximise the use of its domestic resources at all times something which was impossible under the gold standard.

I hope that helps.

best wishes

bill

Sorry Bill, in quoting rvm, I copy-pasted the wrong paragraph! It should have been this one:

“So the US government can buy all available products and services around the globe. What makes USD so special that it turns all the countries into one world private sector and the US government into one world government?”

It is this development that Michael Hudson explains so well in his book.

rvm: “So the US government can buy all available products and services around the globe. What makes USD so special that it turns all the countries into one world private sector and the US government into one world government?”

This is something that I’ve been pondering for a while too. It seems that being the world’s reserve currency permits, to a certain extent, the US to operate globally on MMT principles. There is no actual taxation of the ROW in USD to generate demand for USD globally, but it seems to my naive mind that by, e.g., lending to ROW in USD, denominating various crucial commodities in USD, etc, that an ongoing global demand for USD is created. Collecting interest on USD denominated loans doesn’t seem too different from extracting taxes from the ROW? Although the financial machinery behind it is quite different, a system that compels developing countries to export cash crops to the west in exchange for western foreign exchange seems much like the domestic tax-driven process of persuading people to work for fiat currency in order to earn money with which to pay their taxes.

I was hoping Bill would write about this one day.

Bx12By the way I have yet to hear it answered whether or not Argentina was in fiat currency-floating system when its problems began.

Argentina had a currency board with US dollar peg.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=8322

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=5402

ParadigmShift,

Michael Hudson, makes the point that the rest of the world is dependent on the US because through the World Bank, IMF etc (essentially branches of the US government) all countries that got into trouble were structured in such a way that they would be export dependent. Take Germany for example they were delighted that the US opened their markets to them. But unknowingly once these countries were set up for export they had to buy the US dollar because if they didn’t their currencies would appreciate against the $, and they would lose competitiveness so had to buy the $.

Michael Hudson:The sticking point with all these countries is the US ability to print unlimited amounts of dollars. Overspending by US consumers on imports in excess of exports, US buy-outs of foreign companies and real estate, and the dollars that the Pentagon spends abroad all end up in foreign central banks. These agencies then face a hard choice: either to recycle these dollars back to the United States by purchasing US Treasury bills, or to let the “free market” force up their currency relative to the dollar – thereby pricing their exports out of world markets and hence creating domestic unemployment and business insolvency.

When China and other countries recycle their dollar inflows by buying US Treasury bills to “invest” in the United States, this buildup is not really voluntary. It does not reflect faith in the U.S. economy enriching foreign central banks for their savings, or any calculated investment preference, but simply a lack of alternatives. “Free markets” US-style hook countries into a system that forces them to accept dollars without limit.

I don’t see this situation ending anytime soon.

BFG

Thanks, do you have a link to Michael Hudson’s article, or is it from a book? I’d like to read more.

It seems that the mechanisms involved in persuading entities to demand currency you create at no cost to yourself, in exchange for real resources, vary from simple taxation at the domestic level, to a much more sophisticated development of financial architecture at the global level. It seems to me that the “problem” of the world reserve currency issuer having to run external deficits in order to satisfy the demands of the ROW for it’s currency, is more of a strategic benefit (to the US) than a problem per se.

Ah, just seen Henry’s reference to Hudson’s book “Superimperalism”. I’ll check it out.

Michael Hudson’s Super Imperialism

http://www.soilandhealth.org/03sov/0303critic/030317hudson/superimperialism.pdf

Great link, Tom. Many thanks.

@ Brianovitch: Thanks for the link. I also downloaded a stack of articles from the Levy institute – mostly Wray and Galbraith. Want to get to the bottom of this.

@ pb: Your comments make sense to me. But couldn’t they be interpreted as saying that governments need to tax in order to spend? I don’t mean $ for $, but for price stability reasons.

@ Sergei: Please don’t get upset with me. I don’t want the lives of millions to be ruined. My questions are about exactly what policy approach MMT is proposing, and whether it is practically feasible.

@ Tom Hickey: I’m open to the idea that MMT constitutes a good conceptual or accounting framework for describing how monetary systems actually work, post 1971, and would thus allow policy decisions to be made on a more objective and rational basis. The question is rather about the policy options open to governemnts, and whether the MMT understanding of monetary systems reveals radically new options. Its just that in these blogs there are a lot of very bold statements (taxes don’t fund anything, debt is not debt, sovereign governments not financially constrained) which are either, in fact, just being a little over-literal about some things that are actually fairly obvious about life under a fiat currency, or otherwise really beg serious questions about price stability and defict sustainability. I’m just getting really mixed messages.

My guess in that MMT may be a good framework for objective decision-making, and as such would help policy-makers see the need for and feasibility of Keynesian/postkeynesian approaches. This begs another question: is the hyperbole really helping the cause?

cheers

Tim

Bill, Tom,

Thanks for your answers and links (very useful). I’m still fuzzy about some ideas, but I’m sure there will be opportunities to revisit them.

Tim: My guess in that MMT may be a good framework for objective decision-making, and as such would help policy-makers see the need for and feasibility of Keynesian/postkeynesian approaches. This begs another question: is the hyperbole really helping the cause?

MMT just describes operational reality in terms of how the monetary system works and the policy implications of this, e.g., using stock-flow consistent macro models to align fiscal tools with real conditions that data reveal. This suggests options through fiscal policy that are not being ignored or dismissed for reasons that bear little or no relation to reality, at great expense to society. In this case, adopting MMT in place of the current thinking? is like the jump from mythology to science.

As far as the “hyperbole” goes, my experience in the real world convinces me it’s the squeaky wheel that gets the grease. 🙂

The government need not tax not even for $1 to $1, if the spending lead to technological advancements that brought down inflationary pressure. So building that new road might have created demand and pushed up wages a bit higher but by building that road we have opened up new land for new houses that brings down pressure on lack of rental properties and housing prices in general.

The US government may embark on a fully funded “Manhattan Project” type initiative for alternative energy technology. If successful imagine the impact of that on peak oil and avoiding the inflationary pressures arising from peak oil.

Re Michael Hudson’s Super Imperialism: Thanks for the interesting link Tom H.

A recent illustration of the US policy of not allowing foreigners to use their US dollars in their own interests in a significant way was the prohibition a few years ago of China buying out Unocal, 11th largest US oil company with few holdings in the US. China has responded by buying smaller oil and other assets around the world.

The book illustrates as well how exports can indeed be considered a cost for a country, although the alternatives to this for individual countries can be complex.

The Chinese certainly understand how this all works. When one day they decide to stop giving us lots of stuff essentially for free and produce for their own market our material standards of living will drop quite a bit. Warren M. makes this point from time to time. It is odd how mainstream US economists miss this and persist in calling for rebalancing of trade. Of course they miss lots of important stuff so perhaps it’s not so odd after all!