I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

Trump Administration appears to be kicking lots of own goals

Soon after the US President announced – Liberation Day tariffs – I wrote this blog post – US government is pinning its tariff hopes on some unlikely to be realised assumptions (April 7, 2025) – to help readers understand what logic there was, if any, in the decision by the American government to impose wide-ranging and seemingly random tariffs on the rest of the world. The only apparent logic was that his advisors thought that while the tariffs would variously increase the US dollar price on final goods and services available to US consumers via imports, the flood of global investment funds into US treasury bonds, as a result of the heightened global uncertainty would push the US dollar up and offset the tariff impacts on import prices, because all foreign goods would now be cheaper. We now have a few weeks of data available to see whether things are turning out as Trump and his advisors thought. The definitive answer to date is that the opposite trends are emerging which will see the burden of the tariffs borne by the US consumers and producers rather than the presumption of the Administration that the burden would be pushed onto the rest of the world, which would precipitate rapid change in the favour of the US. It seems at present that an ‘own goal’ is being kicked – and – probably a lot of them.

The substantive document that outlines the US government’s hopes post-tariff imposition was written by the Chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors, Stephen Miran in November 2024 – A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System.

He wrote:

Tariffs provide revenue, and if offset by currency adjustments, present minimal inflationary or otherwise adverse side effects, consistent with the experience in 2018-2019. While currency offset can inhibit adjustments to trade flows, it suggests that tariffs are ultimately financed by the tariffed nation, whose real purchasing power and wealth decline, and that the revenue raised improves burden sharing for reserve asset provision.

Drawing on the experience in 2018-2019, during Trump’s first term, Miran wrote:

During his campaign, President Trump proposed to raise tariffs to 60% on China and 10% or higher on the rest of the world, and intertwined national security with international trade. Many argue that tariffs are highly inflationary and can cause significant economic and market volatility, but that need not be the case. Indeed, the 2018-2019 tariffs, a material increase in effective rates, passed with little discernible macroeconomic consequence. The dollar rose by almost the same amount as the effective tariff rate, nullifying much of the macroeconomic impact but resulting in significant revenue. Because Chinese consumers’ purchasing power declined with their weakening currency, China effectively paid for the tariff revenue.

Why might the offset mechanism occur?

Several factors are mentioned – none convincing.

He claims that the tariffs will boost US federal revenue and fiscal “deficit concerns are likely to be allayed”, which make US Treasury bonds more attractive.

He thinks Trump’s decisions to “aggressively deregulate portions of the economy” will boost economic growth and make US assets more attractive.

Global uncertainty also helps given the historical behaviour of global investors to move funds to US Treasury bonds in such times.

You may ask how a strengthening US dollar helps US manufacturers who are trying to sell into a competitive world market.

Miran acknowledged that should the exchange rate offset occur then “U.S. exporters now face a competitiveness challenge insofar as the dollar has become more costly for foreign importers”.

His solution?

An “aggressive deregulatory agenda, which helps make U.S. production more competitive”.

What does that mean?

It would have to include an attack on workers’ wages and conditions given the proportion of those items in total production costs.

He cited this article (April 29, 2024) – A Trillion-dollar Year – which was published by one of the never ending Right-wing propaganda ‘think’ tanks in the US which promotes, in their own words, “free-market solutions”.

The cited article was attacking the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decision to protect people from PFAS in primary water supplies and regulatory rules in the US, in general.

The author thought the costs to business of such protection were outrageous.

He also attacked the EPA for regulating to reduce “tailpipe emissions” in vehicles and to encourage EV use.

However, reducing “paperwork” won’t make the difference between US manufacturing being internationally competitive again versus not being so.

They would have to seriously cut wages.

Estimates in the past found that “China’s unit labour costs” (which combine wage costs with productivity estimates) were around 25 to 40 per cent of the US unit labour costs.

Further, while wages growth is accelerating in China as the emergence of the middle class substantiates, labour productivity growth is more rapid (by some) than it is in the US.

There were of course contradictions in the stance taken by Miran.

He also noted that the US President has “discussed adopting substantial changes to dollar policy. Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy” because from “a trade perspective, the dollar is persistently overvalued, in large part because dollar assets function as the world’s reserve currency.”

If the US dollar, in fact, weakens at the same time the tariff is imposed then the aforementioned ‘offsets’ of the tariff impact on US prices through the exchange rate do not occur.

In fact, the exchange rate impact would heighten the tariff impact and worsen the situation faced by US consumers.

What has happened?

Things are not panning out as Miran suggested.

First, as part of the latest World Economic Indicators release, the IMF suggested (April 22, 2025) that – The Global Economy Enters a New Era.

They pointed to the tariff decisions as resetting the “global economic system under which most countries have operated for the last 80 years” which is creating “epistemic uncertainty and policy unpredictability” and the “attendant uncertainty will significantly slow global growth”.

For once I agree with the IMF.

The IMF has reduced its estimate of US growth from 2.8 per cent (published in January 2025) to 1.8 per cent in April.

According to their calculations, “tariffs account for 0.4 percentage point of that reduction.”

They also increased the “US inflation forecast by about 1 percentage point, up from 2 percent.”

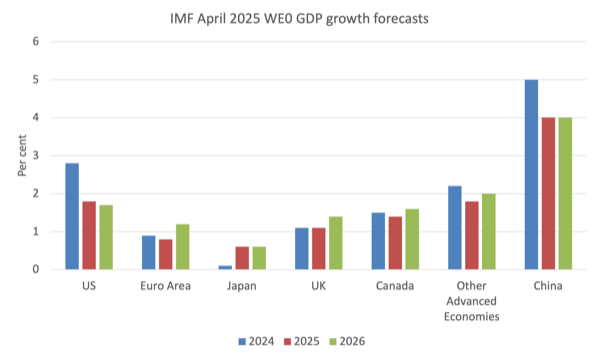

The following graph shows the latest growth forecasts from the IMF.

It is clear that they think the tariffs will damage US growth more than any other nation shown.

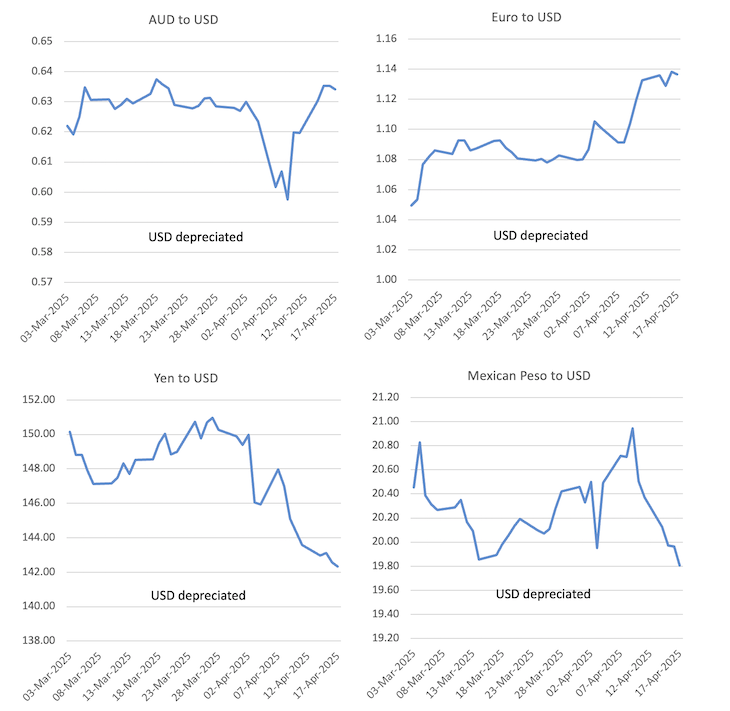

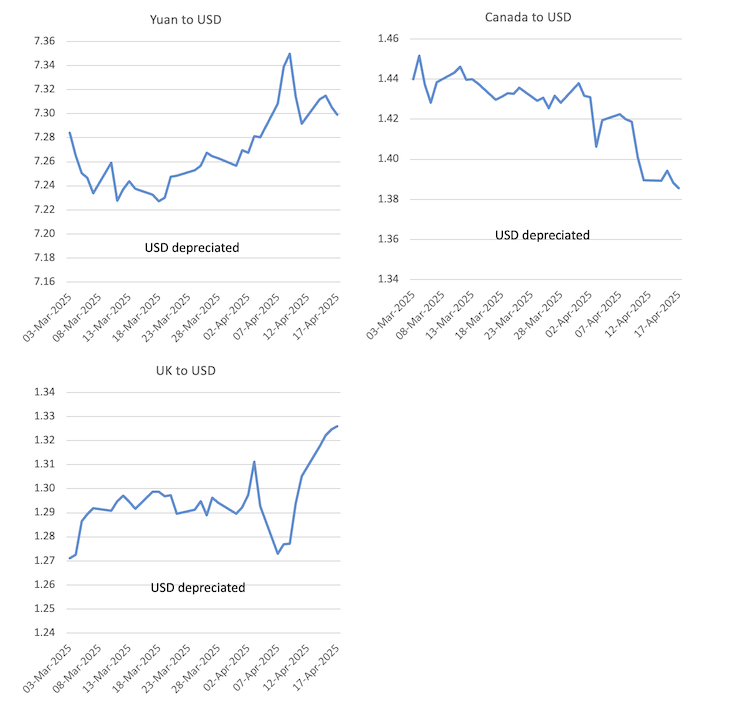

The movements in exchange rates have also been opposite to that required to offset the price impacts of the tariffs.

Here are some selected nations.

Note the quotation in the rates is not uniform, meaning that when the Australian dollar rises against the US dollar, it is an appreciation, whereas, for example, it is the opposite for the yen and peso.

However, in each of the cases shown, the USD has depreciated.

There has also been a lot of news lately about the way the bond markets are defying past history by moving investment funds out of US Treasury bonds despite rising uncertainty that is usually associated with the opposite movement of funds.

Last week, Reuters reported (April 24, 2025) – Japanese investors turned net buyers of overseas bonds last week – that:

U.S. Treasury yields have climbed this month, as bonds sold off, with hedge funds unwinding leveraged basis trades and overseas investors selling U.S. debt in apparent retaliation for tariffs and amid growing doubts about the safe-haven status of U.S. assets.

Japanese investors are the largest holders of U.S. Treasuries with approximately $1.13 trillion in holdings.

Meanwhile, overseas investors have been purchasing Japanese assets, driven by safe-haven demand and expectations that the Bank of Japan is likely to delay its interest rate hike in order to support the economy.

The UK Guardian article (April 9, 2025) = Dramatic sell-off of US government bonds as tariff war panic deepens – also reported similar trends.

It said: “US government bonds, traditionally seen as one of the world’s safest financial assets, are suffering a dramatic sell-off as Donald Trump’s escalation of his tariff war with China sends panic through all sectors of the financial markets.”

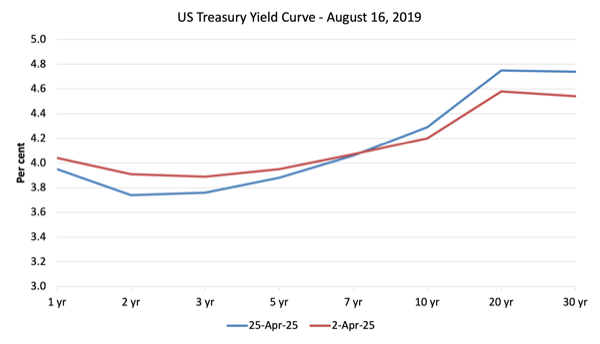

Here is the US yield curve for short- and long-term Treasury bonds on April 2, 2025 and April 25, 2025 (most recent available data).

Not only has there been an overall sell-off but also a switch into shorter-term bonds as the uncertainty increases.

The higher longer-term yields will attract funds back into the US, which we have seen in the last week or so.

But the reality is quite different to that predicted by the Chairman of Trump’s key economic advisory body the Council of Economic Advisors.

Conclusion

It is still only a month or so since the US liberated itself and these processes do not occur overnight.

So it could still work out the way Miran and Co hope.

But I doubt it.

It is looking very much like an own goal at this stage.

I obviously keep my eye on these trends and as they say ‘we will see’.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I spoke to a day trader about a decade ago and asked him how he was dealing with the uncertainty in the financial markets at the time. “Uncertainty?” he replied “We love uncertainty!” Probably had something to do with increased chances for arbitrage or something else that those maths whizzes understand but is beyond my limited comprehension. Nevertheless, old man Trump is dealing out uncertainty in spades. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are folks on financial markets licking their lips at all this. It’s been well documented that western capitalism is really seeing a crisis when it comes to returns on actual investment. Could all this just be the death throes of a system that can no longer produce an increased standard of living?

The ‘sell off’ in Treasury Bonds can only ever be a move to shorter duration at higher prices. In aggregate they can’t go anywhere else. For every sale there has to be a buyer, and the ultimate shortest duration is overnight – aka a bank deposit. So it’s a portfolio reconfiguration.

What I find particularly amusing about the ‘fully funded’ belief system used by the neoliberals is that they never actually sell the bonds the ‘market’ is signalling it wants. Instead they sell a pre-determined spread and don’t seem to change the duration on offer no matter what the economic weather.

If they were truly ‘market led’, then they would order the bonds by yield and sell the ones that are currently the lowest at a limit price. Then rinse and repeat until they’d fulfilled their quota.

I’m not sure that I understand the “revenue” premise of the tariffs. Isn’t this just more of the same error that leads people to believe that the government has to collect money in order to “fund” its spending?

Won’t the tariffs shrink the US economy in the same way that all tax increases (assuming that they result in a net drain barring an offsetting increase in the deficit) do?

Trump intends to reduce income taxes for those earning under $200K with the tariff income. So it’s more of a redistribution.

The price of things will go up, with redirection towards internally produced items. Those people involved in internally produced items will likely earn more and pay less tax, giving them a net benefit.

Those who prefer to consume luxury imports, but won’t receive a pay rise or a tax cut will be the net-losers.

The first set are likely Trump supporters and the second set are not.

Why have I struggled to find, and indeed have not yet found apart from Bill’s contributions, not only a clear and compelling MMT-driven analysis of Trump’s economic program (if one can call it that), but also an MMT-driven alternative economic program to make America great again–something of a much higher order than a paper or post here or there? And please don’t keep giving me the old line that MMT is merely a program-free lens. The ONLY way to demonstrate the clarity and accuracy of a lens is by using what is seen through it to analyze economic problems and propose workable solutions. What did Jesus reportedly identify as the test to determine the truthfulness of a teaching? By the fruit it bears. So I trust I’m not alone when I say that I have abounding faith in the theoretical truth of MMT but remain hungry as hell for the fruit of it in the form of real world demonstration. Come on MMT! Show us the clarifying and magnifying power of your lens by dissecting the failing, flailing MAGA that exists and then, even more so, by fleshing out a new MAGA to “reclaim the state” that once was, for a brief shining moment, a post-war bubble, an exceptional (though far from perfect) nation that worked for the working class.

Sometimes a policy is just not very well thought. I think Trump tariffs are in this category.

Looking at it from the perspective that it will increase local consumption is also not right. It’s not like the blanket tariffs only affect some people, it has macro effects too.

Besides, if Trump wanted, he could have just tariffed luxury goods imports. This will generate revenue too so that the fiscal deficit doesn’t rise while cutting income taxes.

Developing countries do such tariffs to prevent unnecessary exchange rate depreciation from rich people importing luxury goods or gold and making essential goods expensive for everyone in the process. But the U.S. need not do that.

And are tariffs even a good source of revenue? Wouldn’t an ideal tariff generate zero revenue since everything is locally produced?

Tectonic plates—global security arrangements, the reserve currency, global trade—move very slowly.

Globalization must end. It has done enough damage to both the colonized and the colonizers, not to mention the natural world.

Tariffs are but foam on the waves.

The end of the post-WWII economic and geopolitical era is at hand.

America no longer bears the burden of hegemony.

Check back in another 80 years.

@Newton Finn in agreement with you and through social media engagements(reddit) time and again I have stated [International]trade theory and policy recommendations are the final frontiers for MMT. In the overture post by Bill dated 7th of April I put out a comment stating trade for goods + services only accounts for a paltry 25.3 Trillion compared to 1650 for financial assets or ~1.8% Vs 98.2%. As indicated by John T. Harvey even if 15-20% were for covering transactions of goods/services exchanges this is still a whooping ~21% Vs ~79%.

A third crisis of economic theory is brewing?

Not much engagement has come out of that but I have great hunch there’s a massive lode waiting to be found here. There’s much to be done/discovered on this front as domestic, a nation’s jurisdiction, has already been conquered vividly & recently displayed by Kelton’s latest engagement with a Heritage Foundation economist – Steve Moore.

I’d like to have a glimpse of what’s in the minds of the US’s GOP with upcoming mid-terms, ~1.5 yrs away, as I don’t see this being resolved in ~6-12 months. Do American’s have short memory spans not to remember what’s happened in the last ~6-12 months? The Democratic Party seems not to have any answers to this onslaught, the hollowing out institutions in the USA and what they’ve promoted – the end of International Law aka “The Rules Based International Order”. Third and fourth parties will be joining the political foray of the United States?

Regards,

A.Teri