I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

The white hot labour market just went a tad cool

In a way this is an extension of yesterday’s blog where I argued that the gap between the outlandish statements coming from the media and other commentators about how the economy is tracking and the actual data is substantial. Today the ABS released the Labour Force data for February 2010 and the data reveals that employment growth stalled and unemployment rose again. The “markets” (those geniuses) had factored in a solid employment growth which only suggests they know how to extrapolate on recent data points. Further, labour force participation fell which makes the situation even more sombre. So amidst all the talk about employment going ape and wage breakouts about to happen – things have cooled somewhat as the impact of the fiscal stimulus wanes. Yes, its a monthly result and the trend is still mildly positive. But with the declining fiscal stimulus and private spending remaining subdued – today’s data doesn’t signal a steam train economy.

The summary ABS Labour Force results for February 2010 are (seasonally adjusted):

- Employment increased 400 – yes you read that correctly – with full-time employment increasing by 11,400 and being offset by a reduction of 11,000 in part-time employment.

- Unemployment increased 10,700 (+1.8 per cent) to 615,900.

- The official unemployment rate increased 0.1 percentage points to 5.3 per cent.

- The participation rate decreased by 0.1 percentage points to 65.2 per cent and is still well down from its most recent peak (April 2008) of 65.6 per cent. So the approximate number of workers that have dropped out of the labour force because of diminishing job prospects (that is, the rise in hidden unemployed) is 76 thousand persons.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked increased 35.9 million hours (2.4 per cent) which is still well below the July 2008 peak. But that is a solid increase.

- Total labour underutilisation (the sum of underemployment and unemployment) fell by 0.6 percentage points to 12.8 per cent reflecting the rising full-time work and declining part-time opportunities.

The ABC News reported that the:

The average forecast in Bloomberg’s survey of 25 economists was for an increase of 15,000 jobs …

So those 25 didn’t grasp the dynamics very well and many of them are still talking about an impending wages explosions in the coming months! They might usefully take a holiday and shut up.

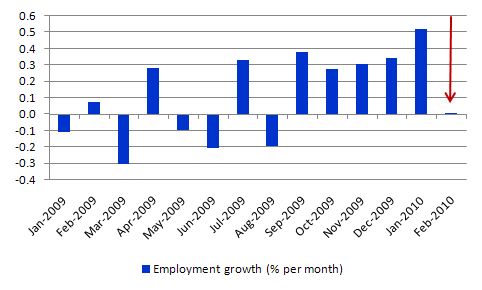

The following graph shows the month by month growth in total employment since January 2009. The red arrow is locating the near zero growth in the current month (January-February) as the spending stimulus from the fiscal intervention starts to wane (and perhaps interest rate impacts are being felt).

A slow recovery in persons employed is not particularly surprising as the economy comes out of a recession. There was a substantial hours adjustment this downturn – more than in the past – and there is a lot of slack there that has to be picked up before firms will really start to hire again.

That might explain the fall in part-time employment and the rise in full-time employment – firms reversing their past rationing decisions.

The only good aspect of the data today is that “full-time employment increased by 11,400, while it was part-time employment that bore the brunt of the job losses (down 11,000)”. This result had to flow-on benefits.

First, aggregate monthly hours worked increased by 2.4 per cent – that is solid. Second, underemployment fell from 7.8 per cent to 7.6 per cent.

The Sydney Morning Herald reports that while the “government’s stimulus spending helped stem job losses during the global financial crisis … [and] … that program’s effect on the economy is fading”, retail firms are “saying the outlook for their business is uncertain”.

The bank economists however are still gung-ho – saying that the result was “rock solid” (which planet does he live on?) and that the data “suggests wage pressure might come back at the end of 2010”. You have to give them credit for persistence.

A strong labour market is not one that sees participation rates falling. The fall in this month took some pressure of the unemployment rate which still rose. Employment growth is not strong enough to absorb the labour force growth.

Having said all of this we have to be careful – the monthly data moves around and the underlying trends are still modestly positive even though they point to rising underemployment still.

But if you look at the data over the last year you do not get an impression of a labour market that is bursting at the seams.

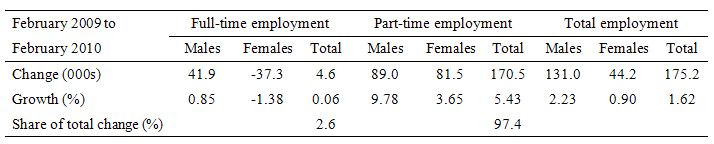

The following table shows what has been happening to employment since February 2009. First, total employment has grown by a modest 175 thousand jobs (1.6 per cent) over that time – the labour force is growing at around 1.8 per cent.

Second, of those 175 thousand jobs, only 4,600 of them were full-time or 2.6 per cent of the total. The employment growth has been swamped (97.4 per cent share) by part-time employment growth.

Third, males and females have shared more or less equally in the part-time growth but the shift in shares is significant. Male part-time employment has grown relatively faster than the corresponding female growth.

Fourth females have lost out badly in terms of full-time employment.

So the small decline in underemployment in the current month, while good news has a strong trend against it at present.

We should also note that while total working hours rose in the current month (on top of the shift to full-time employment) there has been barely any rise over the year to February 2010.

The static working hours on offer at present means that the earnings capacity of workers has been muted over the last year. Real purchasing power has been further eroded by 4 interest rate rises in the that time.

It is thus hard to paint a really gung-ho picture of all of this. Yes, we are doing better than most of the rest of the world but that, in itself, is nothing to be happy about.

The real uncertainty is what is going to happen with the fiscal stimulus in decline and private spending fairly flat on the back of static real earnings growth.

Unemployment

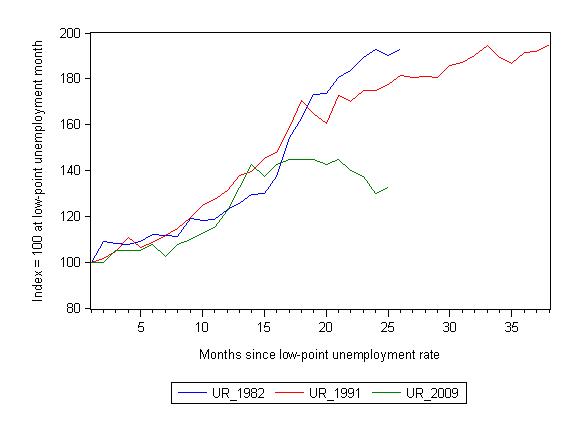

The following graph updates my 3-recessions graph. It depicts how quickly the unemployment rose in Australia during each of the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and now 2009. The unemployment rate was indexed at 100 at its lowest rate before the recession in each case (June 1981; November 1989; February 2008, respectively) and then indexed to that base for each of the months until it peaked. It provides a graphical depiction of the speed at which the recession unfolded (which tells you something about each episode) and the length of time that the labour market deteriorated (expressed in terms of the unemployment rate).

From the start of the downturn to the 25-month point (to February 2010 – the length of the current deterioration since February 2008), the official unemployment rate has risen from a base index value of 100 to a value 132 – a 32 percent rise. At the same stage in 1991 the rise was 77.7 per cent (and growing) and in 1982 90.1 (and just about peaking).

While the unemployment rate was tracking the severity of the 1991 recession up until month 16, it is now clear that the current downturn has parted company with the previous experiences.

Note that these are index numbers and only tell us about the speed of decay rather than levels of unemployment. Clearly the 5.3 per cent at this stage of the downturn is lower that the unemployment rate was in the previous recessions at a comparable point in the cycle.

While many commentators are pointing to increased labour market flexibility after the decades of deregulation for the better outcome this time, this position is hard to argue. The US, for example, is a much freer labour market than Australia’s and their situation is disastrous.

The more robust explanation is that the Australian government implemented the fiscal stimulus very early in the cycle and targetted it to consumers followed by infrastructure. Some of the components were not ideal nor very effective as it turns out but the overal positive impact on confidence and demand is undeniable.

This experience casts an ugly pall over the prognostications of the mainstream economists who for years have been telling their students and anyone else that would listen (including governments) that fiscal policy was dead and monetary policy was the only show in town.

They have no credibility anymore and students should demand better tuition.

Broader labour underutilisation

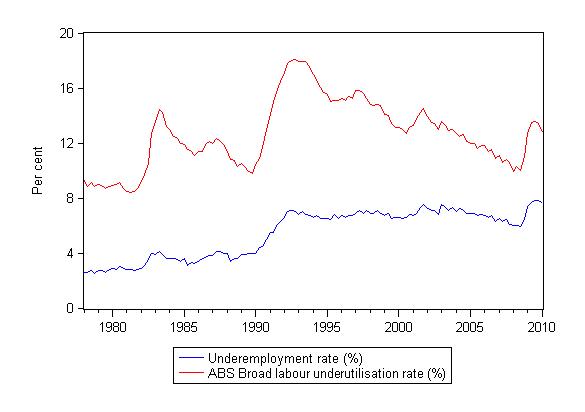

The following graph shows the movement since February 1978 to February 2010 (quarterly data) in the ABS Broad Labour Underutilisation rate (red line) and their measure of underemployment (blue line). The difference between the lines is the unemployment rate.

First, the current level of total labour underutilisation (12.8 per cent) was last experienced in quarter 3, 2003.

Second, you can see the steady rise in underemployment as the economy grew after the 1991 recession. The economy was increasingly reducing unemployment by the creation of part-time work which still rationed the hours available relative to the preferences of the workers (who wanted more). The fact that total underutilisation didn’t scale the heights reached at the peak of the 1991 recession is due to the relatively small rise in the unemployment rate this time.

As you can see underemployment rose more sharply in the current downturn than it did in the 1982 and 1991 recessions. Almost all the labour slack in the 1982 recession was associated with rising unemployment. Underemployment didn’t really become a major issue until the 1991 recession.

Now it has broadened its impact to embrace males. Typically, females have been the victims of the hours rationing.

The rising underemployment, however, calls into question those who are now claiming the labour market is reaching its bursting point. There was a program on ABC Radio this morning with so-called experts calling for higher levels of skilled migration to ease the “shortages”. I won’t link to it because it was a disgrace – one of the experts was emphatic that today’s figures (the program was broadcast before the data came out) would show a decline in unemployment which was now entrenched as “a solid trend”.

So much for the trend.

The discussion in the program didn’t focus on the underemployed which represents a huge wasted skill-base.

Some critics of my position argue that these people have the wrong skills. To which I always reply – the emphasis of labour market programs in the neo-liberal era has been on so-called “activism”. Allegedly, this has involved training and skill development. The Australian government has outlaid billions to its privatised labour services industry since 1998 arguing that the programs would make people work ready.

So with so much labour slack over this period and billions of public dollars being spent on profit-making enterprises trusted with the task of “making people work ready” – then why the hell have we a skills shortage?

Yes, the chronic underutilisation created a new industry – the unemployment industry – and it was full of parasitic firms that took government contracts and returned virtually nothing by way of their stated charters.

Further, there is clear evidence that there are workers available in areas claiming to be in need of skills who could easily do the work or be trained quickly to do the work. The firms however will not hire them. This is a particular problem in areas where there is mining and indigenous Australians live in chronic poverty and joblessness. Pure prejudice is involved in creating this “skills shortage”.

The other agenda of the firms is to claim there are skill shortages because they can then pressure government to allow them to import cheap labour from abroad which is un-unionised and willing to accept terrible working conditions to get out of where they were. Then the local working conditions are bumped down another notch in the race to the bottom.

What the public debate hasn’t considered as yet – so loud are all the conservative voices – is that the debasing of labour conditions is one of the underlying factors that drove the world into crisis. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

Anyway, expect more of the skills shortage nonsense over the coming year as firms avoid their responsibilities to train people properly and the government fails to ditch its ridiculously inefficient and expensive privatised system of labour training program delivery. Its a total joke.

A gross flows comparison of the US and Australian labour markets

In some of my previous blogs on labour force data releases I have presented what is known as gross flows analysis. You might like to read the following blogs – What can the gross flows tell us? – More gross flows – movements between employment and It is easier to keep a job than to get one – as background.

Most of the analysis presented by the media on the state of the labour market (including that above) focuses on the net changes (growth or absolute) and the levels of the labour market aggregates published by the national statistician each month in their Labour Force Survey releases. This data is useful to a degree but cannot really inform you of how dynamic the labour market and whether the dynamics are changing etc.

In this regard, gross flows analysis provides a useful alternative way to interpret what is going on. It allows us to trace flows of workers between different labour market states (full-time employment; part-time employment; unemployment; and non-participation) between months depending on how detailed the particular agency data is. In Australia, we publish flows between full-time employment; part-time employment; unemployment; and non-participation whereas in the US, for example, you can only get the flows between total employment; unemployment; and non-participation.

We can use this data in a Markovian sense, which while placing some restrictions on how we think of the data evolution conceptually, does provide a basis for computing the so-called transition probabilities. These transitions are changes of state (for example, a shift from unemployment to full-time employment) and the probabilities which are computed for each of the these changes are called transition probabilities.

So if a transition probability for the shift between employment to unemployment is 0.05, we say that a worker who is currently employed has a 5 per cent chance of becoming unemployed in the next month. If this probability fell to 0.01 then we would say that the labour market is improving (only a 1 per cent chance of making this transition).

If you are interested in this sort of data I suggest you read the blogs noted above because they have links to ABS references which explain the nature of the data. There are well-known issues with respect to using gross flows data to represent underlying labour market conditions. The major problems are: (a) sample bias present in any survey data; (b) misclassification errors (likely to be small in ABS labour force data); and (c) rotation group bias (significant issue in ABS labour force data).

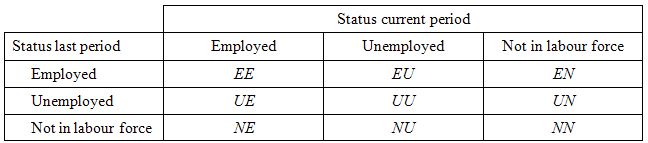

The following table shows the transition probabilities which are computed from the gross labour flows between the broad labour force categories Here E refers to employment, U to unemployment and N to not-in-the-labour force. I am using a 9 cell matrix in this instance because I want to compare the recent history of Australian transition probabilities with what is going on in the US, so I am restricted to computing only flows in and out of employment rather than breaking the latter up into full- and part-time. This is one of those cases where Australian data is superior to that provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The transition probabilities are computed by dividing the flow element for each category by its initial state. For example, if you want the probability of a worker remaining unemployed between the two months you would divide the total flow of workers who remained unemployed by the initial stock of unemployment.

Similarly, if you wanted to compute the probability that a worker would make the transition from employment to unemployment you would divide the flow of workers who were employed last month but are now unemployed by the initial stock of employment. And so on. So for the 3 states (E, U and N) we can compute 9 transition probabilities reflecting the inflows and outflows from each of the combinations. For example, EE is the probability of remaining employed and EU is the probability of moving from employment to unemployment, and so on.

I used data available from the ABS (specifically the GM1 – Labour Force Status and Gross Changes (flows) by Sex, State, Age datacube) and the the latest US Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

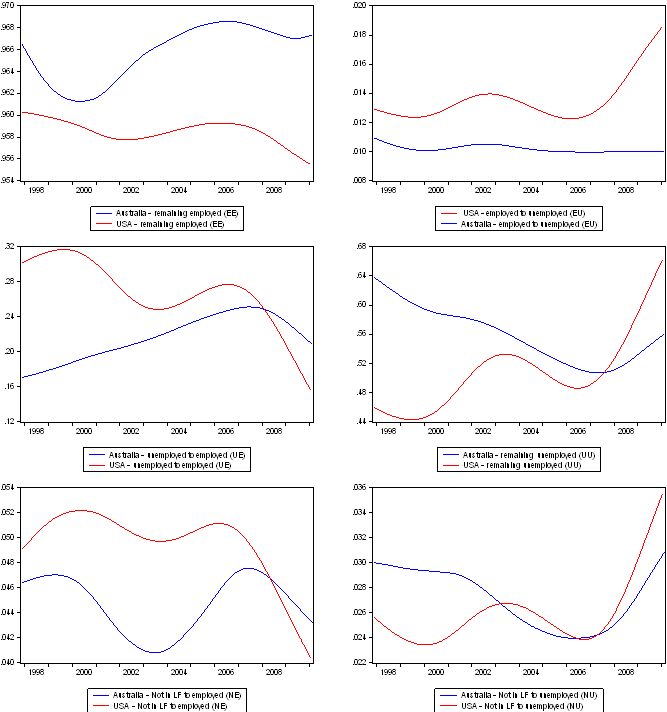

I won’t describe the torturous programming that is required to get the data into usable shape – I do that in the previous posts. The following graph compares the monthly transition probabilities for Australia (blue) and the US (red) smoothed using a Hodrick-Prescott trends to simplify the interpretation.

Even the seasonally-adjusted monthly data is highly variable and messy to graph. While I am critical of the use of HP filters to model potential capacity and steady-state unemployment rates, they are good for depicting linear trends in rather messy high-frequency data. It is questionable whether monthly data is high frequency but it is high enough to be a nuisance when one is trying to extract broader movements.

To make the graph readable I left out the transitions into Not in the labour force (including NN) so have 8 transitions for both countries from November 1997 to February 2010.

There are subtantial differences between the two labour markets but also some notable similarities. First, the EE transitions – the probability of remaining in employment. Over the sample period shown, this has been steadily declining in the US and took a turn for the worst since 2007. For Australia, the change of keeping one’s job has been systematically higher and fell moderately during the downturn and is now showing modest improvement.

Second, the EU transitions – the probability of entering unemployment from employment. The severity of the crisis in the USA is clearly shown here. The chances of losing your job and entering unemployment rise sharply during the recession while for Australia only a very moderate decline. Overall, employed people are more likely to exit employment into unemployment in the US – but other data (duration) shows the likelihood of becoming long-term unemployed is higher in Australia.

Third, the UE transitions – the probability of entering employment from unemployment. Up until the onset of the recession, an unemployed US worker had a higher chance of gaining employment than his/her counterpart in Australia, although the gap was closing. After the recession both labour markets are now delivering reduced probabilities for workers in this regard. The sharp plunge in the US is quite significant from around 28 per cent to less than 16 per cent in the space of 3 years is historically quite stark.

Fourth, the UU transitions – the probability of remaining in unemployment has risen sharply in the US and significantly in Australia. Prior to the crisis an American workers was less likely to remain unemployed (say around a 48 per cent chance in 2006). That probability is now around 67 per cent. So a very bleak outlook. For Australia, the persistence of unemployment had been falling in the last growth cycle but that is now reversing and an unemployed worker has around a 52 per cent chance of remaining in that state.

Finally, the NE and NUtransitions – show the probabilities of a new entrant becoming employed and unemployed, respectively. Both labour markets are moving in the same direction and displaying similar magnitudes in this regard. New entrants now have much lower chances of gaining employment and much higher chances of becoming unemployed.

The transition probabilities do not paint a very rosy picture of either labour market.

Conclusion

In writing yesterday’s blog I could have easily set myself for the same sort of fall that I have been arguing applies to almost all the business economists. They make claims in superlatives – “mother of all booms”, “wages breakouts about to happen”, “white hot labour markets” etc – which they use to buttress their predictions that interest rates will have to rise or fiscal policy has to contract – yet when the data comes the economy doesn’t quite turn out the way they picture it.

My presumption that things are still very fragile is borne out again by today’s Labour Force data.

I don’t consider the data is consistent with an economy that is close to a boom as the banking economists are now consistently claiming. It looks very much like a labour market with a lot of slack still that will take a few years to really wipe out if growth is consistent and government policy is well directed to disadvanted groups and regions.

The other worry – which I am seeing in most of the data releases over the last few weeks is that the signs of the withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus are now showing up. It is not a double-dip scenario yet – as I suspect will apply to Europe, for example.

But it is clear now that the significant rise in the budget deficit boosted the flagging aggregate demand and prevented the labour market from following the path it took in 1991. From the unemployment index graph presented above – it is obvious that the turning point (when the rise in the official unemployment rate started to flatten out) coincided with the early impacts of the fiscal packages.

You cannot escape that conclusion.

But now with the stimulus effects in retreat and private spending far from robust, we are seeing retrenchment in the gains made over the last several months. At present the retrenchment is modest but if the federal government introduce tight fiscal austerity measures in the May budget because the so-called experts are telling everyone things are “rock solid” then we could go backwards.

Given today’s data and related data releases over the last few weeks, I am still of the view that a further fiscal expansion is required – and should be directly targetted at public sector job creation and the provision of skills development within a paid-work context. That would be a great boost to low inflation growth.

Of-course, as usual – I am alone out there among media commentators saying this.

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill,

Can I ask you to comment on the unemployment dynamics in relation to different social groups and different occupations?

Specifically – have you run your transition probabilities analysis for individual segments of the job market in the US and in Australia?

What I’ve found about specific social groups and industries is:

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t04.htm (split by education level)

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t13.htm (split by occupation)

26.5% unemployment rate for “Construction and extraction occupations

Isn’t this situation a direct effect of the housing market collapse?

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t14.htm (split by industry)

Category “Construction” 21.4% (Feb 2009), 27.1% (Feb 2010) – where is the recovery everyone is talking about?

Category “Agriculture and related private wage and salary workers” 18.8% (constant)

This looks to me very similar to the situation in the 1990-ties in Poland where thousands of former state-owned farm workers lost their jobs and could not have been absorbed by any other industry.

(In the end more than 5% of the population left the country after joining the EU)

If we agree that only some of the industries are gravely affected – wouldn’t the indiscriminative stimulus spending be wasteful? Shouldn’t the policy be directly targeting these industries which are in the worst shape?

Bailing out Wall Street hardly helped the builders I think.

What will happen when the housing bubble finally bursts in Australia? You have already published quite interesting graphs about the housing activity.

I post the following propositions for discussion.

1. The variation of private investment policy, as per Keynes, due to “animal spirits”and uncertainty/technical convention variation can be a catalyst of demand deficiency. This means that Fiscal Policy is not the only source of variation of demand failure.

2. A variation in private investment, whether it is financed by debt or share issue, leads to a variation of productive capacity or real capital. Although private debt or share issues cancel out in national account balances, productive capacity has changed. Net Equity Value varies (NEV) by the change of real capital. Thus, Net Wealth (NW) changes and includes not only Net Financial Assets (NFA) or (currency reserves + public debt) but also Net Equity Value (NEV).

3. Growth of productive capacity can sustain private deficit spending, financed by debt and share issues, until increases in danger and diseconomies of scarcity conditions, raise investment costs and/or lower revenues (safety margins) so that the price of investment goods is higher than the price of real capital (Minsky). Thus growth of investment is limited by leverage capacity.

4. Given NFA, money velocity of circulation is flexible enough to accomodate credit expansion which is limited by leverage capacity (Radcliffe Report).

Dear Bill,

I recently found your blog and I find it extremely valuable and enlightening. I have not yet been able to read all the posts but I think I am going to. I’d have a question that is not related to this present entry (for which I apologize). I think it should be easy for you to answer and it’s really bothering me. Feel free to just point me to one of your posts if you addressed this somewhere.

You often talk about how a government doesn’t have a reason to default on bonds issued in their own sovereign currency because they can just print more of the currency. Does it change anything if the government has costly entitlement programs in place that are indexed to inflation?

As I am sure you are aware, the USA is in this situation. I am guessing other developed nations may be as well. It would seem to be that such entitlement programs put some limit the printing presses because significant inflation causes the cost of these programs rise significantly.

Thanks in advance!

Dear Pete

Thanks for your comment and welcome.

In answer to your question – it doesn’t make any difference whether the bond is indexed or not – when it comes to assessing the solvency of the government as the issuer. A national government is always solvent with respect to any obligation that is denominated in its own currency. It always risks solvency for liabilities it undertakes that are not denominated in its currency.

That is not to say that the amount it has to pay out in nominal terms rises over time when there is indexation and inflation. But that is a different issue to solvency.

I also do not use the term – “printing more of the currency” – it is a highly misleading term when it comes to describing the way governments spend and because it is also so emotionally charged it is better put aside. The reality is that governments can always credit banks accounts which is more representative of how public spending (of which interest servicing is just an example) enters the non-government sector.

So in a strict technical sense, there is no financial limit on the nominal spending capacity of a sovereign government. But there is a real limit – and that is defined by what real goods and services are available for purchase at any point in time. The aim of government spending should be to pursue public purpose but also to ensure aggregate demand keeps pace with capacity growth (no more and no less).

best wishes

bill

Thanks for your response Bill!

I wanted to clarify that it is the entitlement programs (in the US: Social Security and Medicare) that are indexed to inflation not the bonds themselves. I don’t suppose this makes a difference as you define the problem and solution at a more fundamental level (aggregate demand and capacity).

I have to say the way you phrase things make the situation appear quite simple and comforting. At the same time there is quite a resistance, I am sure you noticed, to the idea that aggressive deficit spending is a valid response to collapsing demand. I admire your patience on this matter; it must not be easy having to explain again and again that “conventional wisdom” is fundamentally flawed.

As I am exploring your site I have been wondering whether influencing the broader population is one of your goals. I think there is enough basic information on this site to do that (I am not an economist yet I have the feeling (illusion? 🙂 that I understand what you are saying), but it’s not easy to take it all in due to the volume. An easy to find summary (say on the About page or at the top of the Home page), or even just a “map” to a handful existing posts discussing the fundamentals (such as “Barnaby, better to walk before we run”) could go a long way, IMHO. Just a thought.

Thanks again!

bill said: “I also do not use the term – “printing more of the currency” – it is a highly misleading term when it comes to describing the way governments spend and because it is also so emotionally charged it is better put aside. The reality is that governments can always credit banks accounts which is more representative of how public spending (of which interest servicing is just an example) enters the non-government sector.”

What is/are the differences between putting more currency into a bank account and “crediting” a bank account (which in my opinion is actually adding debt to it)?

bill said: “The aim of government spending should be to pursue public purpose but also to ensure aggregate demand keeps pace with capacity growth (no more and no less).”

This probably applies to all spending. Does it matter if it is more debt or more currency?

Bill,

I am really enjoying your blog, and I might even be starting to “get it”. Please put the experience of the 70’s (stagflation) into your theoretical framework.

I, too, would like to hear more about stagflation. That was the watershed experience that made inflation the boogeyman in the U. S. I think that the main rational fear that people have about fiat currency is inflation.