Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

The Australian labour market remains tepid

Today the ABS released the Labour Force data for March 2010 and the data reveals that employment growth is very tentative and unemployment is rising. Unemployment rates in the populous states have risen. Further, labour force participation fell which makes the situation even more sombre. The bank economists have claimed that this is a picture of a near booming economy with wage inflation and skills shortages becoming the main focus. I consider their judgement to be seriously impaired and biased. Amidst all the talk about strong employment growth and wage breakouts about to happen – conditions in the Australian labour market are, in fact, very tepid as the impact of the fiscal stimulus wanes. With the declining fiscal stimulus and private spending remaining subdued – today’s data doesn’t represent a place we would want to be in for very long.

The summary ABS Labour Force results for March 2010 are (seasonally adjusted):

- Employment increased 19,600 (+0.2 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 30,100 and being partially offset by a reduction of 10,600 in part-time employment.

- Unemployment increased 4,200 (+0.7 per cent) to 619,100.

- The official unemployment rate was stable at 5.3 per cent.

- The participation rate decreased by 0.1 percentage points to 65.1 per cent and is still well down from its most recent peak (April 2008) of 65.6 per cent. So the approximate number of workers that have dropped out of the labour force because of diminishing job prospects (that is, the rise in hidden unemployed) is 76 thousand persons.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 10 million hours (-0.6 per cent) which is still well below the July 2008 peak.

- Total labour underutilisation (the sum of underemployment and unemployment) is at 12.8 per cent and constitutes a huge pool of labour that is being wasted despite the rhetoric that we are about to hit skill ceilings.

Soon after the data was published by the ABS today, the Age published their What the economists say page, which they claim is the “experts’ take on the latest economic data”. Somehow the term expert is confined these days to bank economists who all have vested interests in what they publicly say and typically interpret the world through a mindless lens of what it means for interest rate movements. The public debate has become very narrow as a result of this bias.

So typical comments aggregated by me (you can see who made them if you are interested by reading the article) were:

The outlook for hiring is also good with all the investment in mining and infrastructure in the pipeline. That suggests we’ll be running into skill shortages pretty soon, which has to be a concern for the Reserve Bank. We think they will hike in May and this data supports that.

The bigger picture is that forward indicators show unemployment will go lower and there will be skilled labour shortages as the year unfolds, with the accompanying effects of wage inflation.

I don’t think it makes or breaks the case for the next (central bank) board meeting but the vacancy rates tells us that rates are too low and should go higher from here. Yes, we are calling for a rate rise next month.

That’s consistent with the Reserve Bank taking interest rates to more normal levels but then slowing down the pace of tightening, and we’re pretty close to normal levels on lending rates and mortgages now.

The figures today suggest a slowdown in the pace of tightening given it looks like the initial strength in the labour market has given way to a more normal situation.

The conclusion you might reach from reading their statements is that things are fine and there is further pressure on the RBA to hike interest rates again. Further, wage inflation will break out soon as skill shortages emerge. And we are heading back to the “normal situation” after the early (stimulus-driven) growth has faded.

If you think about that for a moment – this “normal situation” is one of entrenched unemployment with employment growth lagging labour force growth. In other words, a NAIRU-type paradise. How uninspiring have our ambitions for people become these days! But then all these economists have stable and extremely well-paid jobs so why should they care.

I just consider the “bank economist” commentary to be such a dismal standard of public discourse.

Even by their own logic, the RBA should only raise interest rates again if it perceives there is a major inflation risk. This data doesn’t indicate a major labour market cost shock which would drive the inflation rate (which is now falling) above the RBA’s upper threshold. In fact, the official inflation rate is barely above the lower threshold of 2 per cent!

There are no wage pressures at present in the labour market except perhaps in the mining sector and that is too confined and small to spillover. The Australian economy is currently resuming its two speed growth pattern which dominated the latter stages of the last boom from about 2004. This pattern is characterised by strong growth in the mining states (Western Australia, Queensland and Northern Territory) and relatively tepid growth elsewhere. The pattern is driven by relatively slow growth in overall private demand being accompanied by very strong primary commodity prices (coming from the Asian boom).

My feeling is that the “two-speed economy” is likely to stifle the RBA interest rate trigger finger.

The evidence for the two-speed economy is fairly strong. Interestingly I don’t agree with very much The Australian (News Limited) journalist Michael Stutchbury ever writes or says (him being an arch-type neo-liberal despite his “Keynesian” education). But in his recent article, which was commenting on Tuesday’s RBA interest rate decision I think he provided some accurate reflections.

He points out that while export volumes in mining are strong, “export volumes for the services sector (including tourism and education), manufacturing and the rural sector have been flat to falling”. He also notes that while mining employment (small overall) is growing fast, “construction, retail, wholesale and manufacturing employment has been flat”.

He also correctly notes that “the lingering credit crunch is squeezing commercial property, housing developers and small business” and that “household disposable income has now fallen in real terms in the past year, after initially being boosted by the federal government’s cash splash stimulus. This is putting the squeeze on consumer spending”.

And today’s labour force data adds extra weight to the two-speed interpretation. The unemployment rate rose in the most populous states of New South Wales and Victoria while falling in Queensland. Interestingly, the strong mining state of Western Australia saw a slight rise in its unemployment rate.

My assessment is that today’s labour force data, contrary to what the bank economists would like us to believe, supports these deflationary trends even though the minerals sector is leading the growth cycle.

I don’t see any case for further interest rate rises coming out of this data.

However, the RBA seems to think it has to keep pushing rates up to their “normal” level (which are ill-defined but around 5 or 6 per cent) so they might just mindlessly continue pursuing that path. But it will be in the context of an economy that evaded the global downturn mostly as a result of a significant fiscal expansion and as that stimulus wanes, the growth path is looking very sluggish and inconsistent (the two-speed aspect). It also happens that the two-speed nature of growth is regionally disparate and the main population centres are stuck in the slow growth cycle.

As to the skills shortage claims I considered them last month in this blog – The white hot labour market just went a tad cool. If you have 12.8 per cent of willing labour resources underutilised (that is unemployed or underemployed) and this situation has persisted for years now then why have you got skill shortages? Even at the top of the last boom the broad underutilisation rate was around 9 per cent. So why isn’t the nation and the “experts” screaming about this.

I know all the arguments – these underutilised people have the wrong skills. To which I always reply – the emphasis of labour market programs in the neo-liberal era has been on so-called “activism”. Allegedly, this has involved training and skill development. The Australian government outlaid billions to its privatised labour services industry since 1998 arguing that the programs would make people work ready. So with so much labour slack over this period and billions of public dollars being spent on profit-making enterprises trusted with the task of “making people work ready” – then why the hell have we a skills shortage?

What you realise is that there is now a new industry – the unemployment industry – full of parasitic firms that rely on government contracts to “manage the unemployed” and return virtually nothing by way of their stated charters – that is to enhance skill development.

There is also clear evidence that there are workers available in areas claiming to be facing skill shortages who could easily do the work or be trained quickly to do the work. The firms however will not hire them. This is a particular problem in areas where there is mining and indigenous Australians live in chronic poverty and joblessness. Pure prejudice is involved in creating this “skills shortage”.

The other agenda of the firms is to claim there are skill shortages because they can then pressure government to allow them to import cheap labour from abroad which is un-unionised and willing to accept terrible working conditions to get out of where they were. Then the local working conditions are bumped down another notch in the race to the bottom.

What the public debate hasn’t considered as yet – so loud are all the conservative voices – is that the debasing of labour conditions is one of the underlying factors that drove the world into crisis. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The skills shortage nonsense will intensify over the coming year as firms avoid their responsibilities to train people properly and the government fails to ditch its ridiculously inefficient and expensive privatised system of labour training program delivery. The whole paradigm has failed and we need a rethink with a central position being given to a Job Guarantee which would integrate paid work and skills development.

But you will never hear the bank economists talking about these issues at that level of nuance … and understanding.

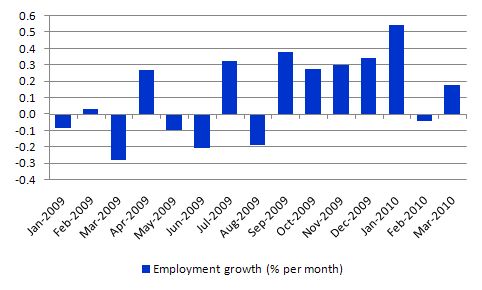

Employment growth weak

The following graph shows the month by month growth in total employment since January 2009. The overall picture is mildly positive but nothing like the rhetoric that we heard from the bank economists noted above. It is clear that the spending stimulus from the fiscal intervention has waned and that private sector spending growth is not yet very strong. So the boost from the stimulus is giving way to a pale labour market recovery.

The other signal that the economy is not booming lies in the continuing (modest) decline in the labour force participation rate – down a further 1 percentage point in March. So the unemployment is rising because labour force growth (despite the drop in participation) is outstripping employment growth.

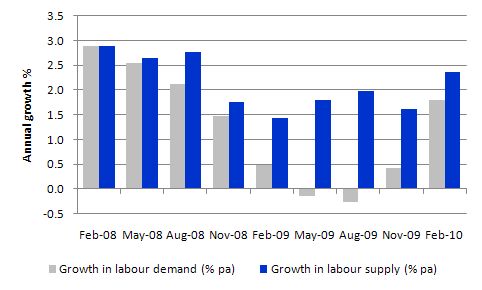

We can combine that information with the newly published vacancy data (see reason in this blog – Rates go up again down here for the reasons for the vacancies data now being available again) to examine the labour market more fully in terms of demand and supply (in persons not hours). Conceptually total labour demand is total employment plus unfilled vacancies. Total labour supply is the labour force (employed plus unemployed) plus those who have been driven out of the labour force because there are a lack of jobs (the so-called hidden unemployed).

I estimated hidden unemployment by holding the peak participation rate in the cycle (65.6 per cent) constant and computing what the labour force would have been if the cycle hadn’t reduced the participation rate. The difference between this measure of the labour force in persons and the actual measure is roughly hidden unemployment. In my academic work I have much more detailed regression-based methods of adding precision to this estimate. But this will do for now and will not be too far off the mark.

So this adjusted measure of the labour force constitutes labour supply – that is, the number of workers who are willing to work at the current wage structure.

The following graph shows the annualised growth in labour demand and labour supply since February 2008 which was the low-point unemployment rate month in the last cycle up to February 2009. This graph adds more weight to my previous comments about the weakness of the recovery. At present labour supply is growing at around 2.4 per cent while labour demand is a sluggish 1.8 per cent. Don’t be surprised to see unemployment continue to rise in the coming months as the hidden unemployed start actively looking for work again as vacancies rise.

The interesting thing is that employment in persons is growing annually in the February quarter at around 1.8 per cent, while unfilled vacancies grew at 1.1 per cent annually in the February quarter. This followed five consecutive quarters of negative growth in vacancies. The recovery depicted at present is very moderate.

Overall, a strong labour market is not one that sees participation rates falling. The fall in this month took some pressure of the unemployment rate which managed to remain steady. Further, employment growth is not strong enough to absorb the labour force growth and the pattern of employment growth is disadvantaging the more populous regions.

And with household real disposal income declining – we are not going to see demand-pull inflation anytime soon.

Unemployment rate

The decline in the official unemployment rate was arrested in March and it sits on 5.3 per cent.

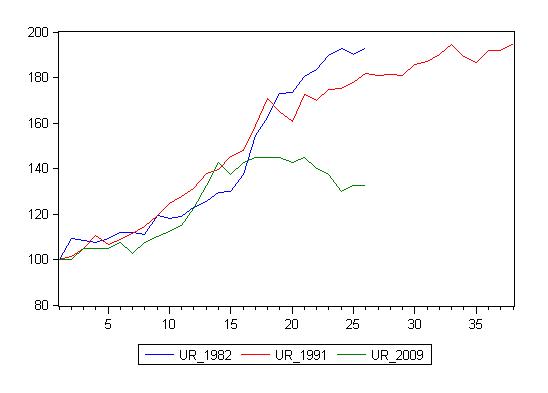

The following graph updates my 3-recessions graph which I produce each month. It depicts how quickly the unemployment rose in Australia during each of the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and now 2009 (the latter to capture the 2008-2010 episode). The unemployment rate was indexed at 100 at its lowest rate before the recession in each case (June 1981; November 1989; February 2008, respectively) and then indexed to that base for each of the months until it peaked. It provides a graphical depiction of the speed at which the recession unfolded (which tells you something about each episode) and the length of time that the labour market deteriorated (expressed in terms of the unemployment rate).

From the start of the downturn to the 26-month point (to March 2010 – the length of the current deterioration since February 2008), the official unemployment rate has risen from a base index value of 100 to a value 132 – a 32 percent rise. At the same stage in 1991 the rise was 81.6 per cent (and growing) and in 1982 92.7. The 1982 recession which was fairly severe ended at the 26-month point and the economy began a painful recovery after that month.

While the unemployment rate was tracking the severity of the 1991 recession up until month 16, it is now clear that the current downturn has parted company with the previous experiences. But the fact remains that the promising employment growth from early 2009 (see graph above) which lasted while the fiscal stimulus was impacting significantly on employment growth is not gone and the retrenchment of the unemployment rate is temporarily stalled. That is bad news.

Note that these are index numbers and only tell us about the speed of decay rather than levels of unemployment. Clearly the 5.3 per cent at this stage of the downturn is lower that the unemployment rate was in the previous recessions at a comparable point in the cycle.

While many local commentators have been claiming the superior relative outcomes in the most recent downturn compared to the 1991 and 1982 expereinces are the result of increased labour market flexibility after the decades of deregulation, the argument doesn’t hold water. The US, for example, is a much freer labour market than Australia’s and their situation is still very grim.

The more robust explanation – especially when you examine the profile of the employment growth in the first graph, is that the Australian government implemented the fiscal stimulus very early in the cycle and targetted it to consumers followed by infrastructure. While there have been some problems with a couple of the programs the overall result has been positive for the economy.

Progressive economists now have some lovely graphs available to demonstrate the fallaciousness of the mainstream arguments that fiscal policy is an ineffective tool for managing aggregate demand.

Hours worked

Total hours worked in March fell by 10 million hours (-0.6 per cent) which conflicted with the commentators who saw last month’s rise in hours worked as being a sign of a developing trend. We should always be wary of making anything out of the monthly movements. There is no strong positive hours trend yet – a fairly weak positive trend is more like it.

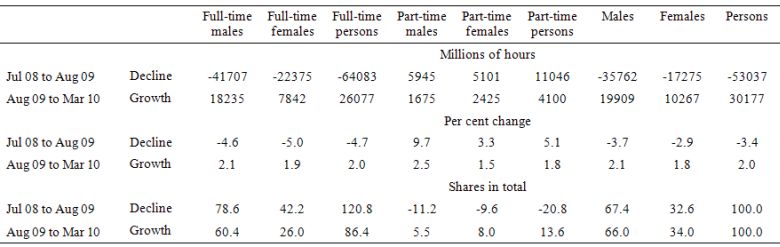

In the following table I decomposed the monthly aggregate hours worked data into full-time and part-time by gender. The data is available from the ABS HERE.

Total hours worked began to decline in the downturn in July 2008 (lagging the rise in unemployment which began in March 2008). The trough was reached in August 2009 (so a relatively short downturn by historical standards for Australia) and have shown steady growth since. So I divided the period from July 2008 to March 2010 in the period of decline and the period of growth.

The first two rows of the Table just show the raw change in millions of hours from the start and end of each period. So during the decline, all of the loss in total hours came from the loss of full-time work given part-time hours rose. During this period underemployment also rose more quickly than official unemployment.

The third and fourth rows are the percentage growth of each of the categories for the two periods to give you an idea of proportion. In the 8 months of growth, we have still not recovered the hours lost in the 13 months of decline. However the cycle is looking very V-shaped indeed.

The final two rows compute the shares in total hours lost for each of the categories. The results are interesting. Males and females shares in the decline and recovery are almost exactly symmetrical. Further, the full-time growth just slightly dominating the growth period which suggests that underemployment will only exhibit modest reductions.

But it is interesting that the economy is adding full-time working hours back in a similar speed to the shedding in the decline – again a very V-shaped cycle.

What about hours by sector? The following graph shows the seasonally-adjusted aggregate monthly hours worked by industry sector from March 2008 (the low-point unemployment quarter) to March 2010 indexed to 100 at the start of the crisis (March 2008). The data is available HERE.

It provides an interesting picture and some counter to the increasingly shrill cry from banking economists that the private market sector is running into skill shortages.

Hours worked in the market sector (primarily private sector) suffered the greatest percentage decline over the course of the downturn and are only showing modest signs of recovery. Total hours worked overall is strongly influenced by the subdued nature of the market sector given its size (around 77 per cent of all hours).

The behaviour of the non-market sector is interesting and given its bias towards public sector activity or derivatives demonstrates the impact of the stimulus packages which began around December 2008 into early 2009.

Conclusion

While the business economists are claiming that the labour market is strong the facts belie that assessment. There is some growth but it is tepid and not sufficient to really make inroads into the labour underutilisation problem.

My presumption that things are still very fragile is borne out again by today’s Labour Force data.

I don’t consider the data is consistent with an economy that is close to a boom as the banking economists are now consistently claiming. It looks very much like a labour market with a lot of slack still that will take a few years to really wipe out if growth is consistent and government policy is well directed to disadvanted groups and regions.

It is also clear now that the significant rise in the budget deficit boosted the flagging aggregate demand and prevented the labour market from following the path it took in 1991. From the unemployment index graph presented above – it is obvious that the turning point (when the rise in the official unemployment rate started to flatten out) coincided with the early impacts of the fiscal packages.

You cannot escape that conclusion. But with the stimulus effects in retreat and private spending far from robust, we are seeing retrenchment in the gains made over the last several months. At present the retrenchment is modest but if the federal government introduce tight fiscal austerity measures in the upcoming May budget because the so-called experts are telling everyone things are fine then we could go backwards.

Given today’s data and related data releases over the last few weeks, I am still of the view that a further fiscal expansion is required – and should be directly targetted at public sector job creation and the provision of skills development within a paid-work context. That would be a great boost to low inflation growth.

That is enough for today!

Bill,

I’m off topic, but before I’m lost completely I’d ask you or any of the posters to help me clarify…

In the answers and discussions from March 20 you wrote:

“(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive in in surplus, negative if in deficit.”

Shouldn’t it be the other way round => (S – I) – if savings are higher than investments than the private sector is in surplus?

Best Regards

“Given today’s data and related data releases over the last few weeks, I am still of the view that a further fiscal expansion is required – and should be directly targeted at public sector job creation and the provision of skills development within a paid-work context. That would be a great boost to low inflation growth.”

Otay…You are correct in that the only one hiring (for quite some time) will be ‘the employer of last resort’. In a world already swimming, nay, drowning in ‘funny money’ (admittedly, this ‘money’ is sequestered and isolated, the current holders couldn’t spend it if they wanted to. [Because it would be very difficult to ‘liquidate’]) (Not to kick an educator in the shins but) what part of the public sector is capable of stimulating the ‘productive’ economy enough that the deficits won’t turn the local currency into confetti?

It is one thing to claim to have assets worth ‘X’ and quite another to actually sell them for that amount.

I’m not pointing to a lack of ‘paper’ assets as much as a dearth of buyers…unless you want your economy to fit inside a dixie cup.

Dear Tomme

Thanks very much for your comment. Yes that is true. It was a typo I will correct it.

best wishes

bill

Wonderful post Bill, comprehensive as always.

I am hunching however on at least another 50 bp in cash rate rises this year (at least).

Thanks for another excellent and accurate assessment of the labour market Bill. As one of the 619,000 unemployed persons who is rapidly losing everything I’ve worked for during my whole life, I find myself perversely hoping that the unemployment rate will increase so that the bank economists and other mainstream commentators realise there is still a massive problem here. With the Leading Indicator of Employment now having fallen for three consecutive months, it is clear that there will not be much job growth in the short-term future so I may get my wish. I also agree totally with your comments about the privatised Job Network. It’s a real tragedy that the old Commonwealth Employment Service was abolished. Most people would be unaware that the main function of the Job Network is that it is an outsourced compliance arm of Centrelink. It is far more focused on compliance than actually helping people find work. My gut feeling is that there might be a rise in the unemployment rate next month, although the figure that really matters to me is the number of unemployed persons, which will also probably rise next month, sadly.

Dear Rationalist

I wouldn’t disagree with your interest rate assessment. The RBA is hell bent on reinstating their “neutral” settings (without any validity for that concept) and will slowly hike during the year unless we go backwards which is not out of the question once the May budget is brought down.

best wishes

bill

Employment Topic.

Just to add some antidotel evidence of what a coal boom looks like. My brother works in a coal mine in Central Coastal Queensland. He said when the recent cyclone was closing on his area recently 115 ships were sent out to sea from local ports to ride out the storm in deep water. That’s a boom for sure. The other odd thing about Mining in Australia is the fly in fly out workers. Now fly in fly out may be needed for realy remote parts of the world but in Queensland they are doing it from places like Emerald which is hardly remote.

Why? Don’t know for sure but it could be the fact the Government has not developed regional cities with all the services people want and need to bring up their families. You cant just keep growing Brisbane and using it as a dormitory suburb for mining in the whole state. I think there are some serious structural problems in the distribution of workers. Workers should gravitate to where to jobs are just like capital seeks out the most rewarding return.

On capital is there any difference between what I think of as real capital: Money that has been saved after tax and now ready to invest and borrowed capital. Seems to me real capital gets crowded out by borrowed capital during lending booms. Any fool with a bankable sounding idea gets funded in a boom crowding out the real capital that ends up sitting on the sidelines waiting for the end of stupidity. Anyone to answer welcome.

We have just had a week of perfect head high surf in South East Queensland in perfect weather and 25 deg water. Sweet as.

Does it not seem to others that the Govt is fighting the Govt because it doesn’t understand the effect of its own monetary and fiscal policy? For instance this is a post of unemployment which is effect by the RBA decision to raise/lower interest rates. However the RBA has been loading up the interest rate lately “seemingly” in response to peoples infatuation with a single asset class, housng. However it is quite clear that this infatuation is driven by the tax incentive “investors” get by purchasing property (negative gearing, capital gains ) and also cash splashes such as the first home buyers grant/boost.

So to me this seems to be monetary policy (interest rates) fighting fiscal policy ( tax incentives ) and creating a complete mess. Does anyone else see this ? or am I making this up in my head?

Dear hoju at 11:43 pm

You said (asked):

For years monetary and fiscal policy have been working together under inflation targetting framework at the expense of high employment and low levels of labour underutilisation. They took the ideological decision to make fiscal policy passive to ensure the policy primacy went with monetary policy.

With the crisis, they realised this was not going to deliver anything sensible and for a time broke with the neo-liberal mould that they had forged since the early 1990s. Now, the neo-liberal ideology is reasserting itself and fiscal policy is being dragged back into its conservative role as a passive partner of monetary policy.

The best policy mix is to set interest rates permanently to zero and then control demand and specific asset class price bubbles with targetted fiscal policy.

best wishes

bill