I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

L’horreur economique

Tonight’s blog title L’horreur Economique is taken from one of my favourite (though depressing) books by a French writer (Viviane Forrester). I will discuss the book a bit at the end of the blog. But I was thinking about it (and re-reading it) today when I reflected on the US President’s most recent Radio address on the reining in budget deficits. We – collectively – have allowed the most grotesque set of lies, half-truths and irrelevancies to become the centrepiece of the public debate on the economy. The crisis exposed the lack of credibility that mainstream economics has and should have dispatched the ideas to the rubbish bin forever. Instead, as unemployment and poverty rates continues to rise the mainstream ideas are now taking centre-stage again. And the policies that result will be to our collective misfortune. It really is “L’horreur economique”.

On Friday, January 29, 2010, the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis released the December quarter national accounts, which showed that the real output growth in the US for the final quarter of 2009 was robust (5.7 percent annualised) and probably consistent with the beginnings of a sustained recovery.

I say probably (with a caution) because most of the growth came from inventory building and the slowing government spending has started to act as a brake. The inventory cycle is an important indicator of firm expectations about the future. When they are pessimistic about the state of aggregate demand they draw down existing inventories rather than commit to new production. When the cycle starts to turn and they regain some confidence they start re-building the stocks in store. This is what has been happening in the last quarter of 2009.

The other point to note from the data is that the household saving ratio continues to rise – courtesy, ladies and gentlemen of the fiscal support that the deficits are providing to aggregate demand. Households could not have successfully pursued a renewed saving program (as a sector) unless this fiscal support was forthcoming.

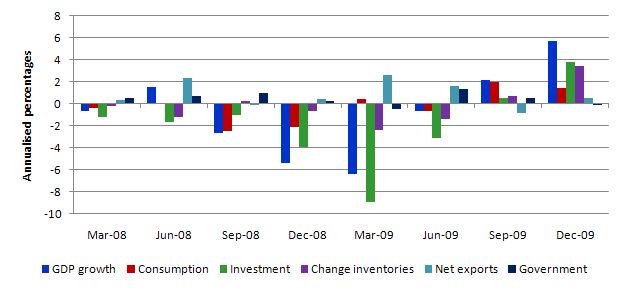

The following graph (using data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis) shows GDP growth (annualised) and the percentage point contributions to that growth from household consumption, private investment, change in private inventories, net exports and government overall.

You can see that as private spending collapsed, the government contribution increased and supported demand in mid-2009 through to September. The public contribution while positive was clearly not sufficient to maintain growth (this is in contradistinction to the Australian situation where the public contribution to GDP growth in 2009 was responsible for the positive growth we experienced).

It is clear that the public contribution to growth is now negative in the December quarter and so the US economy will have to rely on relatively fast growth in the other components. I would not be willing to bet that, in the face of further fiscal contraction, private spending will grow sufficiently to maintain robust GDP growth into the 2010.

But what is also clear is that the deficit terrorists just cannot understand the essential sectoral relationships that link the government, private and external sectors. They seem to think that you can have everything – a budget surplus and high private saving and debt reduction. You cannot unless you suddenly start net exporting in great volumes, which isn’t going to happen in many countries anytime soon, and cannot be a general solution for all nations as a whole (because for every external surplus there has to be equal external deficits).

This came home very starkly in the US President’s Weekly Radio Address on January 30, 2010. In that speech, the US President spends 5 minutes and 13 seconds telling us how these GDP figures make it more critical “to rein in the budget deficits”.

As an aside, my advice to the production team for the videos that accompany the addresses is that the President’s head is too close to the top of the screen. I guess I concentrated on style because the content was so bad. I don’t expect them to improve the content any time soon so better that he doesn’t look “too flat headed”. Then I suppose a flat head is appropriate given he is preaching “flat earth” economic theory – see my blog – Flat Earth theory returns – budget aftermath – for more on that topic.

On matters of substance – the speech confirms that Obama’s neo-liberal advisors are in total control and that the US is going to limp out of this crisis in even worse shape policy-wise than it went into it. The future – stay prepared for the next recession. My summary assessment: the address was worse than his State of Union address, if that is possible.

He opened by noting that that the GDP figures were pointing to growth as a “sign of progress”. That is clear as I noted above. I would also note that the economic growth is already working to wind back some of the US national government deficit via the automatic stabilisers, although in the case of the US the cyclical factor is smaller than in other nations because the tax and welfare system is less sensitive to the cycle than elsewhere. The budget position changes by about 0.4 per cent in the US for every 1 per cent change in GDP.

He claims the growth is “an affirmation of the difficult decisions we made last year to pull our financial system back from the brink and get our economy moving again”. There is no doubt that the fiscal stimulus – even though it was relatively modest and hasn’t been fully spent yet – has put a floor under US production. The same findings will be demonstrated in all countries which have been free to expand fiscal policy no matter what tawdry revisionism will be conducted by the conservatives in the period ahead as to what actually happened.

Get used it – fiscal policy works when applied sufficiently to address the problem at hand which is the decline in overall non-government spending growth.

The fact that unemployment rose everywhere and in some countries, including the US, to obscene levels indicates that the fiscal stimulus packages introduced were insufficient. They helped but were too small relative to the need.

Obama then claimed that as well as growth his “mission” is “grow jobs for folks who want them, and ensure wages are rising for those who have them” which means that:

… job creation will be our number one focus in 2010. We’ll put more Americans back to work rebuilding our infrastructure all across the country. And since the true engines of job creation are America’s businesses, I’ve proposed tax credits to help them hire new workers, raise wages, and invest in new plants and equipment. I also want to eliminate all capital gains taxes on small business investment, and help small businesses get the loans they need to open their doors and expand their operations.

So tax credits – a mainstream stunt disguised as a progressive job creation strategy. I have considered the issue of tax credits before. Please read the following blogs – The enemies from within and Direct public job creation now being debated – for more detailed discussion on why the proposal will not be an effective means of eliminating unemployment.

First, you note that the US Government takes no direct responsibility for providing jobs for the unemployment. While the number one mission for this year is job creation there are no jobs to be created in government by the government (apart from normal business). So this emphasis on jobs is not a reflection of a progressive insight that there are a myriad of productive activities that the US government could be pursuing which would increase employment.

Rather, it is a cop-out that the only jobs worth creating are in the private sector and that the government will seek to extend corporate welfare to that sector to try to induce them to create the jobs. More handouts to the private sector – that is the mission of the US government.

Second, as soon as I see so-called progressives offering tax credits as a solution to chronically high unemployment at a time when aggregate demand is still way too low I know they do not understand how the monetary system operates and the opportunities that system provides a national currency-issuing government. For if they possessed that comprehension they would never propose tax credits as a “progressive” solution to unemployment.

Tax credits are proposed by “deficit-dove type progressives” who think that budget deficits have to be wound back as GDP growth resumes and should largely be balanced on average over the business cycle. That is, run surpluses in good times and deficits in bad times. The aim, which is misguided in the extreme, is to keep the public debt ratio in line with the ratio of the real interest rate to output growth – supposedly, a sustainable fiscal position.

Deficit-doves worry relentlessly about the public debt to GDP ratio because they assume that the “credibility” of the government debt will be compromised and that this (whatever it means) matters.

They consider there is a limit to the size of the deficit (and public debt) but rarely associate this with the requirement that the government has to match the leakages from the expenditure stream arising from non-government saving. So they fail to admit that by placing artificial limits on the deficits this really means that they cannot guarantee full employment. In that sense, they abandon one of the basic principles of being progressive – a concern that everyone who wants to work can find it.

If you are going to run a balanced budget position over the business cycle then the private sector balance will on average equal the external balance. So if you are running a current account deficit on balance then the private sector will also be running a deficit on average. You cannot escape the national accounting relationships.

So if you understand these relationships and the nation runs an external deficit (as in the case of Australia, the US etc) then to aim to balance the public budget over the cycle means that you aim for the private sector to become increasingly indebted over the cycle. Just the strategy that was pursued in the period leading up to this crisis.

It is an unsustainable growth strategy as we have seen. However, in the case of the US National Accounts data which is showing the private sector overall is still increasing its saving ratio – this strategy is likely to lead to a double-dip recession rather than sustained growth.

Proposals that offer tax credits to the private sector fail to understand what causes mass unemployment. The initial reason firms laid off workers and will not re-employ them is because they cannot sell the goods and services that are being produced. Employment is a function of aggregate demand. Firms will only employ if there is demand for their output.

So you either have to increase aggregate demand overall or directly create the labour demand in the public sector. Tax credits will achieve neither outcome. Why would a firm employ labour if the output cannot be sold even if it can get a reduction in tax?

Moreover, the proposal is based on the idea that the goverment will be able to “save” money compared to say a mass job creation scheme similar to a Job Guarantee, where the government would offer a minimum wage job to anyone who wanted one.

A government that issues the currency does not need to “save” it. It also needs to spend more of it in net terms when there is mass unemployment. The idea that making one’s number one mission job creation then trying to reduce government spending is nonsensical given the current economic climate in the US.

Obama’s claim that his number one mission was jobs was to convince people that he cares. Whether he personally cares or not I don’t know. But what followed tells me he doesn’t care as a leader in charge of the sovereign government or doesn’t understand the system he is in charge off – both of which disqualify him from being in top office in any country.

He continued:

But as we work to create jobs, it is critical that we rein in the budget deficits we’ve been accumulating for far too long – deficits that won’t just burden our children and grandchildren, but could damage our markets, drive up our interest rates, and jeopardize our recovery right now.

There are certain core principles our families and businesses follow when they sit down to do their own budgets. They accept that they can’t get everything they want and focus on what they really need. They make tough decisions and sacrifice for their kids. They don’t spend what they don’t have, and they make do with what they’ve got.

It’s time their government did the same. That’s why I’m pleased that the Senate has just restored the pay-as-you-go law that was in place back in the 1990s. It’s no coincidence that we ended that decade with a $236 billion surplus. But then we did away with PAYGO – and we ended the next decade with a $1.3 trillion deficit. Reinstating this law will help get us back on track, ensuring that every time we spend, we find somewhere else to cut.

If you were going to write the stereotypical neo-liberal “brain dead” case against budget deficits you would be hard pressed to do better than this. All the knobs are being turned in these three paragraphs.

A sense of something out of control – ill discipline – is conjured up.

Jeopardy is being played but not on TV – no, this time it is with the lives of our children and even their children. Interest rate rising to choke off progress.

Families and business and government – all the same – all sacrificing for their kids.

Fiscal rules to stop our dirty hands spending what we don’t have … Beautiful really. Although I much prefered Top Cat as comedy rather than the US President in his blue suit and tie (nice colours though!).

In those three paragraphs, which are just paraphrased from a mainstream macroeconomics textbook like Mankiw you realise the US President hasn’t got a clue about the monetary system of his nation and allows his advisors (who wrote this garbage?) to wilfully mislead the citizens of his nation.

He should resign immediately for saying these things.

First, budget deficits do not accumulate. They are the net position at some point in time of two flows – spending and revenue. What accumulates are the net financial assets that are created in the non-government sector.

The deficit terrorists call these assets the public debt burden whereas in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) they are an integral part of the non-government sector’s wealth accumulation.

At the most basic level, the cumulative stock of financial assets created by net public spending are the exact equivalent of non-government saving in the unit of the currency issued by the national government. Arguing that you want to cut back the deficits means you also want to force the non-government sector (as a whole) to reduce its rate of net wealth generation.

While transactions within the non-government sector (what MMT calls the “horizontal transactions” – see blog Deficit spending 101 – Part 3) can generate new wealth in the currency of issue – it is not net wealth for the sector as a whole. Everything at this level in monetary terms nets to zero.

Second, how exactly will the deficits burden the future generations? Governments who pretend they are still operating under a Gold Standard and therefore continue to issue public debt to match their net spending are continually issuing and retrenching debt. This process continues unabated across the generations. I have never received a letter informing me that I have to sacrifice more now because the government has higher debt. It is a nonsensical argument.

It reflects the childish mainstream textbook models where the debt is paid back in a few periods (so the graph can fit on the page of the book) and so “primary surpluses” have to be run and taxes rise to allow the full debt retrenchment to be made. It is a case of the teaching pedagogy grossly misleading the student as to what really happens. Yet the public rhetoric that seeps into the political milieu is just a reflection of the simplistic rubbish peddled in the textbook.

It may be that taxes overall will rise in the future. They may fall too. But I defy anyone to find a close positive and causal (or even correlation) between tax rates and public debt dynamics over the convertible and non-convertible currency periods. You will never find such a relationship. It is a beat-up.

Governments may choose to increase the tax take in the future if they think aggregate demand is too high in relation to the real capacity of the economy to respond and they want less private spending. That decision has nothing to do with the on-going process of paying back public debt and issuing new public debt.

The only time public debt becomes a burden is when mindless governments like the previous Australian Liberal government (1996-2007) try to pay back all the government debt by running increasing surpluses. Then we felt the burden – but it wasn’t the taxes we were paying it was the progressively degraded public infrastructure; the rundown of schools and universities; the persistently high unemployment and rising underemployment – all products of the deficient aggregate demand driven by fiscal drag.

We also paid for it because the budget surpluses that were achieved in that period squeezed the private sector and, in part, led to the unsustainable build up in private indebtedness. The same can be said for the Clinton surpluses in the US in the late 1990s.

So the burdens are the lost opportunities that result from a government trying to “rein in the deficit”.

Third, interest rates do not rise when there are deficits. Where was Bernanke when this speech was being prepared? I am sure he would admit – as he did in his speech I covered on deflation – Things that bothered me today – that the central bank controls the short-term interest rate and can, if it wants to, control the term structure – that is, all rates along the maturity curve (short and long-term rates).

Interest rates may rise – but that is just a reflection of the monetary policy decisions of the central bank. They may think that aggregate demand is growing too strongly in relation to the growth in real capacity and so try to use interest rate hikes to stifle demand. While this might be related to the positive impact on growth that public deficits have – one would argue that this policy position would reflect good outcomes – a strong economy with lots of employment growth.

I agree that central banks have hiked rates well before the economy has been close to full employment and, inasmuch, as the rates do stifle demand (and that is debatable) then this would be a bad thing. But that would reflect the poor decision-making acumen of the central bank rather than anything undesirable about public deficits.

The point is that Obama as some cock-and-bull idea that deficits draw on scarce saving and drive up interest rates. That is, the standard crowding out argument. Please read my blog – When ideology blinds us to the solution – for more discussion on this point. You could also read the blogs that this search string suggests.

The Classical economists considered that saving responded to interest rates only (mostly!) and were brought into equality with investment by movements in the interest rate. This is the loanable funds doctrine which I have written about before.

In the classical theory, the supply of and demand for capital jointly determined a quantity, namely the total volume of savings and investment, and a price, namely the real rate of interest. Investment was demanded by firms, with more being demanded at low interest rates than at high. Savings was supplied by individuals, with more being supplied at high interest than at low.

Thus a market for capital determined how much of current output would be consumed, and how much saved and invested. This market operated wholly apart from the determination of output. Investment and savings did not affect employment and output, but only the division of output between current consumption and capital formation.

Accordingly, when households desired to save more and spend less the interest rate would fall to ensure that investment rose and aggregate demand stayed unaffected. So via Say’s Law (and Walras’ Law) the economy would always be at full employment via interest rate adjustments.

The loanable funds model also underpins the mainstream claims that budget deficits create financial crowding out of private investment. The fallacious line of reasoning is that there is only a finite supply of saving available and by drawing on it the government pushes up interest rates and chokes of investment.

This proposition is asserted in every mainstream macroeconomics textbook in the world and unsuspecting students are brainwashed into believing it is a reliable reflection of the monetary system they live in. It is not! The depiction is not even remotely close!

We can think of the deficit-debt nexus as a wash. The government just borrows back what it has spent!

Proponents of the logic which automatically links budget deficits to increasing debt issuance and hence rising interest rates fail to understand how interest rates are set and the role that debt issuance plays in the economy. Clearly, the central bank can choose to set and leave the interest rate at 0 per cent, regardless, should that be favourable to the longer maturity investment rates.

There are clearly substantial liquidity impacts from net government positions which I have written about before. If the funds that purchase the bonds come from government spending as the accounting dictates, then any notion that government spending rations finite savings that could be used for private investment is a nonsense.

Only transactions between the federal government and the private sector change the cash system balance. Government spending and purchases of government securities (treasury bonds) by the central bank add liquidity and taxation and sales of government securities drain liquidity.

These transactions influence the cash position of the system on a daily basis and on any one day they can result in a system surplus (deficit) due to the outflow of funds from the official sector being above (below) the funds inflow to the official sector.

The system cash position has crucial implications for central bank monetary policy in that it is an important determinant of the use of open market operations (bond purchases and sales) by the central bank.

Government debt does not finance spending but rather serves to maintain reserves such that a particular overnight rate can be defended by the central bank. Accordingly, the concept of debt monetisation is a non sequitur. Once the overnight rate target is set the central bank should only trade government securities if liquidity changes are required to support this target.

So what the US President fails to understand is that the money used to buy bonds (that is allegedly regarded as financing government spending) is the same money (in aggregate) that the government spent. Deficit spending introduces the new funds to buy the newly issued debt.

Fourth, Obama then went onto use the household analogy. I nearly starting weeping … at this level all reason is gone, all understanding is gone … it becomes just plain gibberish – devoid of meaning.

It is true that “(t)here are certain core principles our families and businesses follow when they sit down to do their own budgets”. Yes the basic principle is that both families and firms have revenue-constraints in the currency of issue because they are users of the that the national government issues as a monopoly.

They thus have to “finance” their spending.

In the long-run, it is also true that “(t)hey don’t spend what they don’t have” in the short-term they borrow and lend to each other to allow different consumption and investment time paths to be followed. But it all has to be “financed” through earnings, borrowing, drawing down past saving, or selling off assets (accumulated from past saving).

To then suggest “(i)t’s time their government did the same” is a denial of the currency issuing monopoly of the government. The government issues the currency that the non-government sector uses. A currency-issuing government has no financial constraints and its prospects are not even remotely like those of a household, unless they self-impose rules that make them so. In doing so, they would jeopardise their capacity to generate high levels of employment and social progress.

I have written several times about the absurdity of fiscal rules. You might like to start with this blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – and then follow through using this search string.

So the speech just got worse rather than better. Spending freezes, bi-partisan Fiscal Commissions, etc – all signs that the US President doesn’t want to provide leadership or use the capacities his government has to advance social purpose. His big 2010 mission is jobs but he is taking zero responsibility for their creation. He is relying on the private sector to react to his corporate welfare initiatives to generate jobs at the same time they will face rising fiscal drag. It is the epitome of non-leadership.

The US President finished by saying:

I’m ready and eager to work with anyone who’s serious about solving the real problems facing our people and our country. I welcome anyone who comes to the table in good faith to help get our economy moving again and fulfill this country’s promise. That’s why we were elected in the first place. That’s what the American people expect and deserve. And that’s what we must deliver.

The real problems facing your country start with the administration you have put in place. Your advisors are poisonous when it comes to meeting the challenges your citizens face. Sack them immediately. I can recommend several good Americans who could take over the economic portfolio and get the solution in place quickly.

But the last thing the US economy requires right now is to withdraw the fiscal support. For now you must ensure that net public spending remains at the level which will support full employment and the private saving desires. My reading of the situation is that you are short by some percent of GDP in achieving this level of support.

Forget the deficit-terrorists – they neither understand or care about public purpose.

So when can we meet Barack and discuss this – given you welcome anyone who comes to the table in good faith?

Future generations etc

Underlying the President’s speech was the intergenerational debate – the so-called ageing society meltdown of the budget hysteria.

I thought this article (January 30, 2010)- Longevity is a triumph, not a problem, by Brendan O’Neill had an interesting view of the matter.

He began by reacting to the recent comments by right-wing British author Martin Amis, who appears to be insulting as many people (movements) etc that he can of late, perhaps because his readership is in decline. Among his recent exploits has been his invocations that UK Muslims should be actively discriminated against (for example, no travel, deportation, strip-searches) until the parents start disciplining their children properly. And stuff like that.

Anyway, O’Neill’s article focuses on Amis’s take on the ageing population debate – the latter described the demographic changes coming as a “silver tsunami” and said that it would be “socially destabilising” and could provoke “civil war between the old and the young”. His solution is voluntary euthanasia.

While not the place to air my own views on the euthanasia debate and you can expect from my Political Compass score that I am in favour of it although I wouldn’t use the language that Amis does.

Further, while the “civil war” analogy is over the top, it does bring the debate out into the domain where it belongs. That is, away from the financial and into the political. All these ageing society questions are political assuming there will be enough real resources around. Even if real resources are exhausted the challenge will still be political. There is never a financial constraint on a national government that issues its own currency.

O’Neill has a similar perspective:

Western society finds it increasingly difficult to value older generations, instead viewing them as a burden on social services and the environment.

The ageing population is most frequently referred to as a problem or ticking time bomb rather than seen as a testament to human ingenuity and leaps forward in medicine and living standards. Older people are now seen, not as sources of wisdom, but as the suckers-up of resources that might be better allocated to younger, healthier people.

In fantasising about erecting euthanasia booths, Amis was only crudely expressing what has unfortunately become a mainstream prejudice: that there are too many old people and society can’t cope with them.

However, O’Neill’s position is that the “ageing population … ought to be seen as a good thing” and shows how we have been extending human life, which, in turn, means our living standards have been rising.

In this vein, he says that “the ageing population is more of a “problem” in developed countries than in poor countries” citing life expectancy statistics for Japan (82.07 years); France (80.87) etc, and Zambia (38.44), Angola (37.63) and Swaziland (32.23). The poor developing world would “love to have the “problem” of an ageing population” – which means, better “sanitation, the victory of medicine over disease” etc.

When considering this debate you have to be very clear to separate issues relating to the availability of finance from issues relating to the availability of real resources.

O’Neill notes that “older people are looked on as burdens on the health and social security system”. For example, the formerly erudite Washington Post, now a scam mag serving the ignorant, said in this article (March 31, 2009) – Recession Puts a Major Strain On Social Security Trust Fund – that:

The U.S. recession is wreaking havoc on yet another front: the Social Security trust fund. With unemployment rising, the payroll tax revenue that finances Social Security benefits for nearly 51 million retirees and other recipients is falling, according to a report from the Congressional Budget Office. As a result, the trust fund’s annual surplus is forecast to all but vanish next year — nearly a decade ahead of schedule — and deprive the government of billions of dollars it had been counting on to help balance the nation’s books.

So the ageing population is constructed as “financial havoc”. The article quoted a conservative viewpoint (a Republican politician) who suggested the retirement income system in the US was in danger of collapse. He clearly doesn’t have a clue about capacity that a fiat currency system bestows on a government. There is no danger of collapse – full stop! The US government for political reasons might curtail some benefits – but these decisions will not reflect financial constraints.

The article’s so-called “balance” quoted a so-called “liberal analyst” (from University of Massachusetts and the Center for American Progress) as saying that “(t)his is not a problem for Social Security, it’s a problem for fiscal responsibility … [the new estimates would force the government] … to stay on track in what they have set out to do, and that is rein in deficits”. You just have to lie down and cry when that is being portrayed as the “liberal position”.

The rest of O’Neill’s article is interesting and he covers the attacks on the older generation for being “unnecessary carbon footprints”; for taking jobs from the younger workers; among other supposed problems.

His closing take is that the “treatment of the ageing population as a problem really reveals today’s lack of imagination and human aspiration” – a view with which I concur.

O’Neill says that unless we “challenge today’s anti-human outlook” we will start asking “What’s the point of old people?”.

This is similar to the argument made by French author Viviane Forrester in her 1996 book called L’horreur Economique about unemployment (you can get the 1999 English version – HERE – essential reading).

In L’horreur Economique the proposition is that governments are failing to generate enough employment but at the same time they are promoting a backlash against those who are jobless. Forrester says that:

The panaceas of work-experience and re-training often do nothing more than reinforce the fact that there is no real role for the unemployed. They come to realize that there is something worse than being exploited, and that is not even to be exploitable…

The book ventures into the notion that governments (elected by us) have made the unemployment dispensable to ‘capitalist production and profit’ and have instead been content to keep them alive. But soon, why would it not be implausible to declare this growing group of disadvantaged citizens totally irrelevant.

So when the unemployed also become aged – what then? The lack of imagination that O’Neill identifies in our attitudes towards to aged is also clearly apparent in the public debates we have about the unemployed.

We hide this lack of imagination in faux financial arguments – “the government cannot afford to create jobs for all the unemployed” [OF-COURSE IT CAN] or there is nothing productive for them to do [OF-COURSE THERE IS] – which thus diverts the debate into a series of non-sequiturs.

If the unemployed are ultimately dispensable for capitalist production (and that is what persistent long-term unemployment suggests); and they cannot do anything productive if we employ them in the public sector (that is the overwhelming view of the deficit terrorists); and they are a nuisance to manage (you know all the arguments – income support corrupts etc) – then ultimately society might start asking “what is the point of the unemployed?”.

Then different solutions might be advanced. Don’t think this is off the track … after all only 70 odd years ago Germany decided that a definable cohort was dispensable and could be exterminated.

L’horreur Economique is one of those books that you just go back to from time to time to remind yourself of the message – just in case you have moved on to the vilification of the aged and left the unemployed behind.

The title could have been used to adequately describe Obama’s radio address.

That is enough for tonight!

Just discovered your blog. Awesome reading. Keep it coming. We need more people like you who will demystify the spin and present a coherent and honest view. You present the argument very well that government can and should be the employers of last resort.

Also forgot to mention that I just ordered “The Economic Horror” from Amazon.

«When considering this debate you have to be very clear to separate issues relating to the availability of finance from issues relating to the availability of real resources.»

Sacred words! That should be considered in *any* economic debate, and in particular as to the impact on the distribution of real resources, which is just about never neutral and rarely small.

«then ultimately society might start asking “what is the point of the unemployed?”.

Then different solutions might be advanced. Don’t think this is off the track»

Your reasoning here is why I find many “progressive” arguments almost as revoltingly hypocritical as those of the “conservatives”.

There is no question that first world “society” has already decided that the unemployed are dispensable, and good riddance to them — if they are brown or dark skinned and live in Asia or Africa. Any “moral” argument for “Guaranteed Income” or similar ideas that does not include the wretched in Asia and Africa etc. is just a veneer of hypocrisy.

«… after all only 70 odd years ago Germany decided that a definable cohort was dispensable and could be exterminated.»

There is a huge difference between “good riddance” to “losers” (whether within the first world or anywhere), the unproductive and uncreative, the vermins of society that nobody thinks are valuable enough to employ, and a policy of active extermination. While many conservatives spite and hate those they regard as exploitative parasites, they usually prefer “good riddance” to an (expensive too) active extermination policy, and enclose themselves into gated communities, and let the losers rot.

The first policy is what “progressive” parties in the first world have adopted just as the “conservative” parties have — tax the rich to provide goodies to their voters, not to the unemployed and poor in general, good riddance to them if they are desperately poor and ill in another country.

When the USA democratic party wants to cut the spending power of the relatively rich workers in the USA to provide free health insurance for the Congo, or the Australian Labor party does the same to provide free health insurance to the Indonesians, then I’ll think that USA and Oz workers don’t think exactly the same as USA and Oz bosses as to there being “dispensable” sectors of society.

The difference between the two is just a matter a degree — for many of the unemployed of the USA and Oz etc. the unemployed of Africa and Asia are dispensable; for many of the employed of the USA and Oz all the unemployed are dispensable. It is “F*ck you! We got ours” all round, the only difference is how exclusive “We” is; basically progressives and conservatives usually differ only in how they define their tribe.

There are two very good arguments for first-world only Guaranteed Income policies to help only the unemployed of the first-world, but they are not based on any charitable or moral sense, which would have to be extended to the much worse off to the credible. They are based on strictly utilitarian and selfish reasoning, and curiously enough “progressives” usually don’t use them, but make entirely fake arguments about charity and human rights. Shame.

«There are two very good arguments [ … ] They are based on strictly utilitarian and selfish reasoning,»

Well, they can also be based on “limited morality”, where a bit of selective charity is better than none, but limited morality has difficult consequences.

«There are two very good arguments [ … ] They are based on strictly utilitarian and selfish reasoning,»

BTW, instead of waiting to be begged to reveal them, they are:

* Reciprocity: it is insurance, and insurance against being poor or sick within a country is reciprocal, not charity. If a rich person pays more into the insurance pool, and a poor person pays less, that will reverse when the rich person becomes poor and the poor person becomes rich. Rich people become poor all the time, and not just thanks to Madoff.

* Liberty: sure, some rich people may think they have no chance of becoming poor, or they may think the poor have no chance of becoming rich, so that they don’t expect reciprocity to work for them. But then they are not forced to pay into a country wide insurance pool: they can always emigrate if they think they are being charged unreasonably for national insurance policies. Citizenship/residence are voluntary bargains when they are not longer of mutual advantage.

The state has in effect two roles; one is to provide some minimum standards of intercourse between members (“Leviathan”), the other is as a group purchasing scheme for things like poverty or sickness insurance, or for roads, or for whatever else; just like a housing association. And membership in such group purchasing schemes is voluntary as long as emigration is possible. Just like nobody is forced to work or shop at Wal*mart, nobody is forced to be resident or pay taxes in any first world country, they can always leave for a country that offers a better bargain.

And since membership and payment of the membership dues is a voluntary choice and the purchasing decisions and distribution of costs are based on majority rule and accountability, it does not need to be extended beyond national boundaries. There is no need to invoke charity or pity (“morality”) in schemes like Guaranteed Income or national health services — just voluntary membership into group purchase of poverty or sickness insurance.

And this goes back to the divide between classes in countries like the USA — the rich tend to want a membership scheme which involves the poor sharing the cost of policing to protect the wealth of the rich, or sharing the risks with (or instead) of the rich of dying in a war, but they don’t want a membership scheme in which they also share poverty and sickness insurance; because hey reckon that reciprocity as to risks covered by policing and military expenses gives them an advantage, while they reciprocity as to risks covered by poverty and sickness insurance is not advantageous for them.

The rich usually want to belong in group purchase schemes excluding poorer people (except for policing and military expenses), and so do the poor (as to even poorer people in other countries). But as long as membership is voluntary and the benefits are reciprocal, that’s fine.

Bill: Second, as soon as I see so-called progressives offering tax credits as a solution to chronically high unemployment at a time when aggregate demand is still way too low I know they do not understand how the monetary system operates and the opportunities that system provides a national currency-issuing government. For if they possessed that comprehension they would never propose tax credits as a “progressive” solution to unemployment.

You seem to disagree with Warren’s proposal of an immediate payroll tax holiday, so I assume you regard his position as conservative, or at least not progressive. If would be interesting to hear a debate on the relative advantages and disadvantages of this.

From the political vantage, I think it would be easier to get the US conservatives to go along with a payroll tax holiday than more spending, but I suspect that Democrats would balk at it as a prelude to getting rid of the tax altogether, thereby threatening the “funding” for SS and Medicare. So there is probably no political advantage in it either.

Warren’s other proposal of giving the states $500 per capita makes more sense politically and economically, since the states are hemorrhaging jobs, as well as cutting back social programs and education, due to declining tax revenue – on which they depend since states must balance their budgets year to year. This could probably pass since a lot of Republican governors would be for it.

Blissex: nobody is forced to be resident or pay taxes in any first world country, they can always leave for a country that offers a better bargain.

Good points; however, I would take issue with the above statement. The poor do not have the luxury of emigration that is open to the rich. They are stuck where they are. The rich would like to make out that the poor either have the opportunity of leaving if they don’t like it (when this is not an option), or else working harder to make it (when there are no jobs available and no entrepreneurial funding for poor people to start their own business, even if they had the wherewithal otherwise).

Dear All,

Unemployment, some would argue, arose in a context of increasing trade liberalization and financial deregulation through a series of negotiations (WTO) that started after WWII, but which really took off in the 1970’s. While it is debatable whether this has created jobs on a net basis (after discounting other factors such as improved literacy and health care in SE Asia), at the very least,

a) increased competition and the fickle nature of shareholder capitalism have created a sense of unease for the non-government population, whether employed or not.

b) it has made terminal losers such as the mill worker of Pennsylvannia whose plant is outsourced to South East Asia or the Mexican peasant that cannot compete with a first world heavily subsidized industrial-like agricultural sector, who is either stuck in an unemployment trap or have to immigrate illegally to find work, respectively. Increasingly, the same phenomenon is afflicting the service industry as well (telemarketers, programmers, accountants).

The “deficit terrorists” are the same zealots who have promoted this agenda, and who tell us that yes, it can be painful, but the pain would be even worse should we even begin to challenge it. While I recognize MMT’s contribution in dispelling some myths about deficits, such as crowding out and that they have to be financed, I have yet to be convinced that under the above described status-quo, asking the government to systematically make up for the shortfall wouldn’t amount to filling a leaking bucket, until the world becomes one big homogeneous place in terms of labor costs, welfare, environmental standards etc. I think I read on this blog, and Paul Krugman tends to argue along those line, that exports are a cost and imports a gain, to the extent that exports divert resources from domestic consumption, but I hope that this will be discussed in the future in a broader debate that includes the implications for employment.

I would find it slightly disingenuous to suggest, as perhaps Economic Horror seems to do, that the specialized and therefore narrow skill-set and probable lack of formal education (not to be confused with foolishness) of says a mill worker, can be wiped away by the magic wand of government sponsored job creation. Un-productive government jobs do exist, when they are in response, not to a genuine demand for public goods, but solely as a desperate attempt to address unemployment. They don’t fool the beneficiary and they create resentment towards him/her, and government at large.

PS: Anyone of you reading these lines feeling knowledgeable about EMU, please note that I have posted a technical question in yesterday’s post, “Things that bothered me today”. I’d really appreciate some feedback, is possible.

So,

Am I correct in concluding:

Functionally, quantitative easing (buying back Government bonds) is equivalent to never bothering to issue bonds in the first place. All it does is drain relative liquidity from the private sector, relative to what it would be if the Government issued those bonds. This is what would happen if the Government did not raise its “debt ceiling” and did not bother to “finance” its budget deficit. The issuance of government bonds is not a fiscal operation, but a monetary one.

Speaking in US terms, wouldn’t it make more sense to just give the Federal Reserve discretion over whether or not to issue Government bonds (or to not issue them), at any time, in any quantity, regardless of what the “government debt” is – solely for purposes of regulating liquidity and the amount of safe stable assets (government bonds) in private portfolios?

Suppose the Federal reserve bought back $1,000,000,000,000 in bonds from the private sector – could it not simply reset its “net position” to 0, thus “defaulting” on its “debt”, rather than -$1,000,000,000,000, with no real ill effects? All that would be different would be a number in a spreadsheet, am I right?

I think a big part of the problem is that Government “debt” is referred to as debt. It is not debt. It is something else entirely – the Government in a fiat currency system with floating exchange rates CANNOT go into debt, in the sense that a family can. True, it can have negative numbers on a spreadsheet, without consequence, but numbers on a spreadsheet with no consequence is not what people think of when you say the word “debt.” Referring to it as “debt” is misleading to average people because it triggers the cognitive analytical framework of debt (from the perspective of users rather than issuers of currency) that they know about from their own lives.

If I am right in my understanding of this, then we should stop referring to “Government debt” as Government debt. It is like calling a harmless kitten a menacing tiger. We need a more accurate term for it, or to outright deny its very existence as a meaningful real thing.

Matta, the monetary purpose of issuing Tsy’s to drain excess reserves, as well as OMO, is to allow the Fed to balance the overnight rate in the interbank market with its target rate so that excess reserves don’t drive the overnight rate below the target rate (or, in the case of OMO, raise it above the target rate if reserves are insufficient). The Fed could just set a support rate on excess reserves at its target rate instead of using government “borrowing” to drain excess reserves. Then banks would not underbid the target rate with their excess reserves. Randy Wray recently made this proposal in Memo to Congress: Don’t Increase the National Debt Limit!

Using “spending” and “borrowing” in relation to government fiscal and monetary operations is confusing because it reinforces the false analogy between government and non-government finance, when they are in fact opposite in the sense of being complementary.

Progressives should stop using such terminology that is ideologically based and find a more appropriate way of framing it using concepts that are reality-based, rather than being sucked into the conservatively biased conceptual morass of the prevailing universe of public, academic, and political discourse. See Douglass C. North (Nobel ’93), “Economics and Cognitive Science”, which shows how conceptual memes ground social convention that in turn gound economic and political institutions. See also cognitive scientist and progressive activist George Lakoff’s The Political Mind: Why you can’t understand 21st-century American politics with an 18th-century brain. “Visceral politics” is Lakoff’s brief response to a reviewer that summarizes the thrust of the book. Critics of REH and EMH will also be interested in this, since cognitive science shows the rationality “hypothesis” to be false based on brain functioning.

I agree with Bill that tax credits are a rubbish idea. The idea has been around for decades: e.g. Richard Layard (former Prof of Economics at the London School of Economics) used to advocate the idea. If anyone wants to plough through the literature, try Googling “marginal employment subsidy” – that was the phrase used by Layard etc. to describe the idea.

One of the (rubbish) arguments behind this idea (if I remember rightly) was that firms base prices on marginal costs. Tax credits reduce marginal costs. Ergo Tax Credits reduce prices. And given constant AD in money terms, this means a rise in AD in real terms, and thus more jobs (or at least an improvement in the inflation/unemployment trade off).

I take a swipe at the idea here, if anyone is interested:

http://margemsub.blogspot.com/

Dear Mattay and Tom Hickey,

I recently made the point to Bill about referring to government debt as “debt”. He has used it several times in his blog. My background is in computer science and not economics, so when I first started to become acquainted with Bill’s work several years ago I found the use of the word “debt” in this context very confusing. Of course once you become sufficiently familiar with MMT etc then you know what is meant but for the uninitiated it is extremely confusing. What’s more and worse it allows the ignorant or deceiving politicians and business interests to keep the public in the dark and exploit them.

Perhaps a new terminology should be introduced for this sort of “debt”. What about imaginary debt or soft debt as opposed to real debt or hard debt? Anyone got any better suggestions?

best wishes

Graham

Angry Bear has a post by guest Martin Ford, An Alternate Theory about the Root Cause of the Current Economic Crisis attributing the crisis to the increasing role that automation is playing in globalization, making a lot of workers redundant and increasing structural unemployment. Fits in with Viviane Forrester’s argument.

This developing process of globalization under a neoliberal and neoconservative agenda is also frequently critiqued from a variety of angle at PROUT.

Bill, it would be interesting to have your thoughts in a post on a progressive “new world order” instead what the West is now trying to impose on developing countries as the model. This model is now called into question by the crisis, which as undermined confidence in the superiority of the neoliberal model, and at the moment the chief contender as a replacement is the Chinese model, which is hardly satisfactory either.

Hey Graham,

I like the Real/Imaginary dichotomy between private sector and government debt.

“Real Debt” is private sector debt, generally known as “debt.” This debt has very real effects, and must be paid back or financed somehow. It is not simply a number entered on a spreadsheet. Real Debt is the sort of Debt that ordinary people are used to thinking about.

“Imaginary Debt” is government debt. This “debt” has no real effects, and need not be paid back or financed. It is simply a number entered on a spreadsheet, and someone could do data entry to change the number in the spreadsheet to 0 without any Real effect, because (again) this is Imaginary Debt. Note also that this would not be defaulting on Real Debt, because it is Imaginary Debt. It is not possible to default on Imaginary Debt, because it is Imaginary, not Real.

We ought not to even bother keeping track (accounting for) Imaginary Debt, because it is Imaginary, not Real. Because it is not Real, Imaginary Debt is not debt at all. Just as we don’t account for Imaginary People, Imaginary Food, Imaginary Cars, or Imaginary Money, we should not account for Imaginary Debt. I don’t care that the US has an Imaginary Debt of 12,000,000,000 any more than I care that Ford produced 5,000,000,000 Imaginary Cars last year. I only care about Real Debt and about Real Cars.

Matta,

> Speaking in US terms, wouldn’t it make more sense to just give the Federal Reserve discretion over whether or not to issue Government bonds

FYI, the interplay between the Fed and treasury was asked and answered in the commentaries following the post “the progressists have failed to seize the moment”.

By the way National Debt and Household debt are already different names; it’s the implications that are misunderstood. Besides, from the standpoint of the bearer of a bond, “debt” still retains its original meaning (a promess to repay), whether it’s corporate or sovereign.

Matta, national “debt” is real in the sense that Tsy’s represent net financial assets of non-government. It is also a Treasury liability. However, it doesn’t have to be “paid for” by taxation, as most people think. When a Treasury security is sold or redeemed, this is simply recorded on the Fed’s spread sheet as transfer of one asset (the security) to another (corresponding amount of bank reserves). As far as the Fed is concerned, this nets to zero on its book. Non-government net financial assets are neither increased or decreased. Monetary operations do not do this, only fiscal operations.

If the security is redeemed on maturity, then the liability is extinguished on the Fed’s balance sheet. If the security is sold by one party to another party, then it’s just a transfer of reserves between the banks involved. If the Fed buys the security, it moves the security to the asset side of its balance sheet and increases its liability by adding the corresponding amount to the selling bank’s reserve account. Then, if a private party sold the Tsy, the commercial bank involved just adds this amount to the seller’s deposit account.

While currency issuance and management are largely “imaginary” from the side of the government, they are real from the side of non-government because increases and decreases in non-government net financial assets have real effects in the economy. Of course, when the government issues physical currency as Fed notes or minted coins, this is real rather than being just a number on a spread sheet. It’s probably mostly why people think of money as being real and why they have no idea of how the monetary system operates. I suspect that a lot of people believe that all monetary transactions are actually in cash, and that the cash is sitting in their bank’s vault or at the Treasury when they pay taxes, for example.

The problem with terms like “debt” and “borrowing” is that they convey the idea that the government must finance its spending from the public’s savings that were generated by the economy, whereas the reality is that the government is just providing a way to hold the net financial assets it creates in disbursements as interest-bearing securities, like “time deposits,” that are risk free. Government securities function in non-government as a convenient parking place for net financial assets, and within the reserve system as a monetary operation that does not affect non-government net financial assets, only how they are voluntarily held.

Dear Tom,

yes, I agree, but it is the confusion that is not clarified for the citizenry when they make initial attempts to understand what is going on; it is a didactic issue. To that extent it might be good to have some alternative term just to avoid the bamboozlement, perhaps only for use in educational situations. As a result I have just about given up on trying to encourage the uninitiated to get their heads around MMT and JG matters. They lose momentum very quickly as did I and it is only because I knew Bill as a colleague and friend that I persisted.

This also throws up the prolific use of acronyms (eg REH and EMH in your comment above) and jargon in the financial and economics realm. Of course jargon (or terminology) is needed for differentiation and precision but nevertheless it is a formidable barrier for beginners.

How about a glossary and list of acronyms for Billy Blog? Maybe it could be arranged in such a way that those making comments can add to the list rather than expecting Bill to do it all.

Also Tom, I’ve been reading those books of Chomsky which you mentioned a couple of weeks back. I got the distinct impression that he doesn’t have much understanding of economics (spelt MMT), i.e. is caught in the “official line”, as he might call it. Or do I have the wrong impression?

Best wishes

Graham

Love this blog. Its amazing you can post in such detail and still have time for anything else. Keep fighting the good fight.

I think you are being a bit too hard on Obama though. As you mention, government-household budget equivalence is the standard in every macroeconomics textbook at the university level. It is hard to see how it is Obama’s fault for failing to buck what most economists both in government and academics hold as fact. Perhaps it comes down to leadership, but remember that you can’t play if you don’t have the cards to play with. The unemployment situation in the US is bad, but it is not desperate. There are not millions upon millions destitute and poor like in the Great Depression. In fact, one of the most pressing issues voters mention in public opinion polls is the size of the deficit. So until another great crisis changes this sentiment, Obama will have no choice but to toe the line and talk tough on deficits.

Graham: yes, I agree, but it is the confusion that is not clarified for the citizenry when they make initial attempts to understand what is going on; it is a didactic issue. To that extent it might be good to have some alternative term just to avoid the bamboozlement, perhaps only for use in educational situations. As a result I have just about given up on trying to encourage the uninitiated to get their heads around MMT and JG matters. They lose momentum very quickly as did I and it is only because I knew Bill as a colleague and friend that I persisted.

No doubt that this is a didactic issue. I recommend getting Warren Mosler’s 7 Deadly Innocent Frauds down pat because he has aimed it didactically at people who know zip about the subject. But just about everyone buys into the myths that Warren demolishes with facts. I regularly recommend that folks start with the 7 Deadly Innocent Frauds and build on that. I also cite it as the first reference on other blogs when bringing up these matters because it is accessible to most people. Although Warren is a proponent of JG, he doesn’t get into it here since this piece is meant to be introductory, disabusing people of their erroneous ideas and false assumptions. Most people think in metaphors, and the primary metaphor that people use in misunderstanding monetary economics is the government-household finance analogy. Warren does a great job setting this straight.

This also throws up the prolific use of acronyms (eg REH and EMH in your comment above) and jargon in the financial and economics realm. Of course jargon (or terminology) is needed for differentiation and precision but nevertheless it is a formidable barrier for beginners.

I just through this in as an aside for people that are into the currency controversy over Rational Expectations Hypothesis and the Efficient Market Hypothesis. It’s not really germane to this discussion.

Also Tom, I’ve been reading those books of Chomsky which you mentioned a couple of weeks back. I got the distinct impression that he doesn’t have much understanding of economics (spelt MMT), i.e. is caught in the “official line”, as he might call it. Or do I have the wrong impression?

Chomsky looks at the problem from the point of view of a political ideology that is being foisted on the world as the basis for a “new world order” (not the conspiracy theory that goes by this name), which is based on neoliberalism (laissez-faire capitalism) and the Pax Americana (neoconservativism). He is not interested in critiquing neoliberalism as an economic theory, but rather demonstrating its use as a non-military strategy (backed up by overwhelming military force) based on the vaunted superiority of the American Way in achieving national prosperity, and ultimately global prosperity.

Even if the economics were correct, Chomsky shows how it would still be a bad deal for most people because it tilts the playing field toward capital in the name of achieving prosperity and advances the superiority of an elite in governing in the name of democracy. Basically, this “new world order” is based in the idea of “the rich mans’ burden” for which the wealthy are rewarded disproportionately at the expense not only of the welfare of the rest but also their well-being and even survival.

Dear All,

I hope I’m not over-posting by adding this bit of research taken from the post “A greek tragedy…” :

1/ The ECB with its NCBs is the fiscal agent of the governments

2/ “Article 101 of the Treaty forbids the ECB and the NCBs to provide monetary financing for public deficits using “overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the ECB or with the central banks of the Member States”.

regarding my question about EMU (2 days ago) and that I rephrase here : is net spending, a horizontal transaction, or a vertical transaction (as in the US)?

Specifically, 1/ seems to suggest that G-T>0 is credited to banking system by the ECB (via NCBs), but according to 2/, only by debiting funds that have to be available beforehand. In other words, the government must borrow first, from the banking system, before it can net spend, which is a horizontal transaction. If so, net assets would have to be created through a different channel then. Which one?

Somebody asked me my thoughts on Obama’s latest proposals to introduce another job creation program, coupled with attempts to reduce the long term budget deficit. I said it was like having an open house whilst simultaneously putting explosives on the door knobs.

Regarding new words to replace the “spending” and “borrowing” that the government does, the technical term that the government uses for spending is “disbursement,” however that is not entirely satisfactory as a replacement because it still suggests spending, when what the government is actually doing is providing “money” as non-government net financial assets. Therefore, “provisioning” would be more accurate. While this sounds awkward now, it would be worked into an entirely new frame of reference that replaces the current frame based on the government-household analogy and the gold standard. Actually a lot of provisioning isn’t spending at all. When the government disburses SS funds to recipients, it is not itself purchasing any goods or services in the economy.

Similarly, when the government creates debt instruments (Tsy’s) it doesn’t borrow from the savings of non-government but rather provides a way for non-government to hold the funds it provides through its prior disbursements, using risk-free interest-bearing securities. This is a voluntary service of the government, not a financial requirement, and the monetary operation of draining reserves that accompanies security issuance could be accomplished otherwise, e.g., by paying a support rate on excess reserves. The framing should reflect this fact. The accounting shows that the transaction involved in security issuance is essentially the switching of one asset form to another. But, importantly, the government also disburses funds as net financial assets to non-government through the interest paid on the securities it issues. This is also a form of currency issuance, so it is a type of provisioning. The framing should reflect this fact as in a term like “interest-provisioning.”

We really need the framing to reflect the essential vertical-horizontal relationship of government and non-government finance. Using the same or similar terms obscures the framing and confuses the issue. Presently, this is the problem, and it is a framing problem in the cognitive sense. I would say that this is a very high priority if the debate is to become reality-based instead of taking place as it is now, in the context of a flawed ideology.