I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When ideology blinds us to the solution

It is interesting how one’s ideology screens out options and alters the way we examine a problem. I was reminded of this when I read two articles in the Times the other day (December 23, 2009) – Thrifty families accused of prolonging the recession and – No evidence Britons can save the day which both focused on movements in the savings ratio. The claim is that with UK households now saving more to reduce their exposure to debt, the UK economy is facing a double dip recession. The ideological screening arises because they seem to think it is inevitable that rising savings will lead to a deepening recession. In doing so they fail to realise that the moves by the British government to “reign in the deficit” are the what will make this inevitable. If their world view was less tainted both articles would have focused on the spurious nature of the deficit terrorism rather than the desirable trend towards rising saving ratios in Britain (and elsewhere).

I juxtapose this sort of reasoning with the New York Times editorial on December 22, 2009 – Americans Without Work which in one paragraph tells us all why the deficit terrorists should take a vacation and let those who know something about the way the economy and the monetary system operates design the policy path to take us all out of this malaise. More later on that.

Note the use of the term policy path – that reflects a broader set of options than the Times articles are able to see – in part, because the rhetoric expounded expresses the blinkered understanding of the available options that the resurgent neo-liberal ideology is now imposing on the public debate.

The main claim of the article – Thrifty families accused of prolonging the recession is that:

Anxious families are repaying debts instead of spending in the shops, amid concern over the uncertain economic outlook. The share of income saved in banks and building societies has risen to its highest level in more than a decade, heightening fears that faltering consumer demand could prolong the recession.

The savings ratio – the gap between household income and spending, which is often used to repay debts or add to savings – soared to 8.6 per cent between July and September, the highest level since 1998.

According to the Office for National Statistics the saving ratio is:

… household saving expressed as a percentage of total resources which is the sum of gross household disposable income and the adjustment for the change in net equity of households in pension funds. Household disposable income is the sum of household incomes less UK taxes on income, and other taxes. contributions and other current transfers, which are all compiled by the ONS. Household saving is what remains of available resources after deducting households’ final consumption expenditure expenditure, also compiled by the ONS.

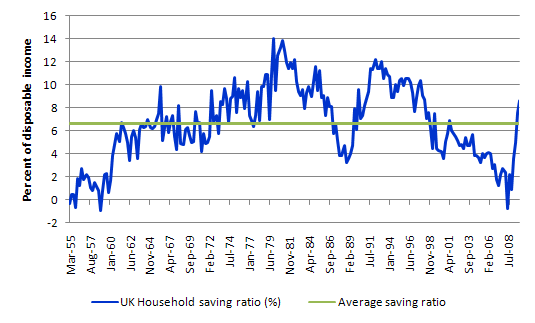

The following graph shows the evolution of the UK saving ratio in since 1955 (quarterly data from the ONS). The green line is the average for the whole period (6.5 per cent) and the blue line is the actual ratio. I had a look at GDP growth over this period and when the saving ratio was stable around the average so was GDP growth (at about 2.5 and 3.5 per cent per annum).

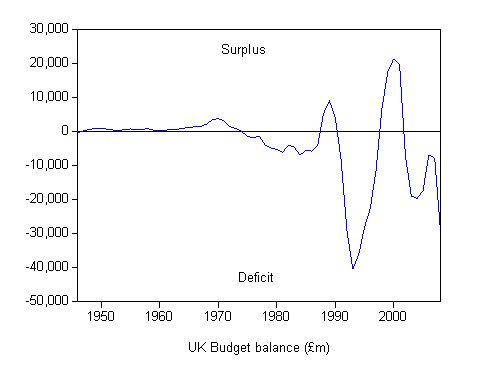

This graph shows the national budget balance over a longer period (and not the last several months) but it allows you to examine the more recent period and juxtapose it with the movements in the saving ratio. Note when the recession impact of the early 1990s recession which plunged the budget into deficit as you would expect after the short attempt at pursuing surpluses which drove the saving ratio below the zero line (into the negative). You can see that the deficit allowed the household saving ratio to recover in the mid-1990s.

Then the surplus mania hit again and this squeezed aggregate spending and drove the saving ratio towards the negative again and the main reason that the UK economy grew during this period was that British households starting piling up huge volumes of debt. The story repeats itself over many economies.

Unless the economy has very strong net export surpluses, budget deficits drive the production system into recession and only a short-term credit binge can forestall that inevitability.

So you can see the saving ratio has risen sharply in the UK in the last year or so but it only just above the long-term average.

The Times Article said that “analysts fear that consumer spending, which rose by 0.1 per cent in the third quarter, its first growth since the start of the recession, will remain muted as households continue to repay debts and save.”

The ONS reported that people net borrowing is falling compared to the binge in the years preceding this.

The Article notes that:

The economist John Maynard Keynes argued that while saving may be a virtue for an individual, a nation of people doing the same would slow the economy. This in turn would hurt those trying to save more. He called this the paradox of thrift.

The other Times article written by Ian King – No evidence Britons can save the day also focused on recent trends in the UK savings ratio. King said:

On the face of it, news that the savings ratio has risen to its highest level since 1998 ought to be good. Britain’s households have been living beyond their means for most of the noughties and, as recently as 18 months ago, the savings ratio was close to zero. It was even negative for the first three months of 2008.

So, in theory, anything that helps to restore order to household finances should be welcomed. Or should it? As John Maynard Keynes pointed out, excessive saving at a time of recession can do more harm than good, a phenomenon he called the paradox of thrift.

So Keynes, who was shunned by the neo-liberal years by commentators as being dinosauric, in now back in vogue. The use of the term dinosauric relates personal experience. I have been regularly called a “Keynesian dinosaur” by mainstream economists over the last 20 years or so. I always laugh – for two reasons.

First, the arrogance of this lot (new classicals, monetarists whatever) to think that “the business cycle was solved” – please read my blog – Those bad Keynesians are to blame – for more discussion on this point.

It was clear if you suspended the ideological obsession that deregulated markets are self-regulating and budget surpluses underpin saving – that the business cycle was going to get really ugly this time round. The modern monetary theory (MMT) writers were publishing this sort of prognosis in the second half of the 1990s.

Second, the mainstream crowd are actually so ignorant of the broader economics literature that they conclude I am a Keynesian and are not acute enough to realise that MMT is not a Keynesian approach.

It has some elements that are consistent with what Keynes wrote but then I would say that these elements are not dissimilar to what you read in Marx (especially Theories of Surplus Value) when he talks about effective demand. Within the MMT camp there are some who lean more to Keynes that is true. But then there are those such as me who do not.

Anyway, Keynes is back in fashion – well partially. Everyone is talking about the paradox of thrift but seem unable to take this further to achieve a fuller understanding of the problem and the solution.

Keynes certainly understood the essential relationship between income growth and saving growth and the role that net public spending can play to support both.

Both Times’ writers, however, conclude (in King’s words) that:

Accordingly, it can be argued that if this pick-up in the savings ratio genuinely reflects a greater desire by households to spend less of their incomes and save a greater proportion, it could torpedo any hopes of a return to meaningful economic growth next year.

So you see how constrained the thinking has become which takes me back to my opening point. The dominance of the neo-liberal period in ideological terms has changed the way people consider problems.

They no longer think that the government has the solution via fiscal policy. They are wedded to monetary policy as being the dominant counter-cyclical tool as a result of years of conditioning that inflation-first policy was sound. Now that low interest rates and billions of QE have built bank reserves with little to show for it (and why would anyone be surprised by that anyway) they think that the aggregate policy policy options are exchausted.

This is especially because while fiscal policy has been significantly ramped up – it is now reached the point where the comfort levels that are conditioned by this neo-liberal ideology have been exceeded. It was always an excercise in discomfort for the governments to expand net spending and at each step of the way they were talking exit plans and sustainable outcomes etc. All negative talk focused on some magic number – a ratio of deficit to GDP or something else equally irrelevant.

It is absolutely essential that British households (as a sector) now maintain saving ratios around around the long-term average for several years to come to reduce their exposure to debt. A growth strategy built on public surpluses and growing private indebtedness was always going to come unstuck.

The prolonged recession in Britain has been an exemplary depiction of that rule. The household debt ratio (debt as a percent of total net disposable income) rose to over 180 per cent in the UK and this is higher than most advanced nations.

The Times writer Ian King notes that the financial engineering boom in the UK undermined the desire of households to save in over the last 15 or so years. He implicates “the savings industry” which was involved in the “mis-selling of both pensions and endowment mortgages from the late 1980s onwards”; some notable financial scandals (for example, Equitable Life); and poor regulation of the life insurance industry.

He reported that a recent study “revealed that 90 per cent of UK households have less than £50,000 in financial assets- including their defined contribution pensions – and average financial wealth of just £7,000.” So the credit binge and its reversal has not made the British (on average) very wealthy.

His conclusion is that:

It would be nice to think that, eyeing what could be a prolonged recovery in savings ratios, the UK financial services industry might now be engaging its best brains to create a suite of easily understood, low-cost products that would appeal to such households. On the industry’s track record, though, it would be unwise to expect as much.

However, if he wasn’t constrained in his thinking he would also have argued that there is a need for sustained budget deficits in the UK to help to “finance” the return to a postive saving ratio is also shown by the fact that Britain has mostly enjoyed the benefits of a current account deficit since the mid-1980s (with a short period of surplus around 1997).

The current debate in the UK about fiscal consolidation (which is the neo-liberal term for raising taxes and cutting spending) is absurd in this context a point I will return to later. But in the light of household saving trends, the situation in Britain will become dire if as the national election approaches the Government persists in its tough fiscal line.

Households are likely in this event to try to build an even larger buffer stock of savings (but will be thwarted by negative income adjustments). So while GDP has already fallen according to the ONS by around 6 per cent since the second quarter of 2008, the future will look even grimmer unless the policy makers really understand what an application of “Keynes” means in a fiat monetary system with flexible exchange rates.

But first, how do public deficits “finance” private sector saving? This takes us back to Keynes (and Marx).

The Classical economists considered that saving responded to interest rates only (mostly!) and were brought into equality with investment by movements in the interest rate. This is the loanable funds doctrine which I have written about before.

In the classical theory, the supply of and demand for capital jointly determined a quantity, namely the total volume of savings and investment, and a price, namely the real rate of interest. Investment was demanded by firms, with more being demanded at low interest rates than at high. Savings was supplied by individuals, with more being supplied at high interest than at low.

Thus a market for capital determined how much of current output would be consumed, and how much saved and invested. This market operated wholly apart from the determination of output. Investment and savings did not affect employment and output, but only the division of output between current consumption and capital formation.

The concept is still dominant among textbook writers and mainstream commentators. This search string will locate my blogs where I have discussed this before.

Accordingly, when households desired to save more and spend less the interest rate would fall to ensure that investment rose and aggregate demand stayed unaffected. So via Say’s Law (and Walras’ Law) the economy would always be at full employment via interest rate adjustments.

Keynes demolished this logic and showed instead that saving was predominantly driven by income growth. He started by reviving Marx’s earlier works on effective demand (unknowingly or without explicit recognition – he was hostile to Marx). What determined effective demand?

There were two major elements: the consumption demand of households, and the investment demands of business. Here Keynes attacked the classical loanable funds theory by demolishing their vision of the capital market.

Keynes attacked the supply curve conception in the loanable funds doctrine. He argued that savings had nothing to do with the interest rate. They were, instead, merely the residual after households had consumed from their income.

Investment, did depend on the interest rate. But a curve of investment demand alone could not determine both the volume of investment and the rate of interest.

From a theoretical perspective, Keynes now needed an independent theory of the interest rate. Keynes analysed a new market, up to that point largely ignored in economics: the market for debt instruments and, in particular, for money. He argued that interest was not a reward for saving, but the reward for giving up the liquidity, the easy access to immediate purchasing power, that could be had by holding money.

As anyone who has bought a bond knows, the longer the term (the greater the liquidity foregone), the higher the rate of interest. Keynes argued that the interest rate thus reconciled the supply of liquidity (quantity of money) with the demand for it. And in Keynes’ new sequence, the interest rate determined in the money market in turn determined the volume of investment.

To complete his theory, Keynes tied these elements together. The market for money determined interest. Interest (together with the state of business confidence) determined investment. Investment, alongside consumption, determined effective demand for output. Demand for output determined output and employment. Consumption out of incomes determined savings. Employment determined the real wage.

So when you introduce a government sector to this economy you quickly understand that if the non-government sector is spending less than they earn (a spending gap) then the government sector has to be running deficits equal to that gap for GDP (aggregate output and income) to remain stable at full capacity.

If the government does not support the desire to save by the private sector then the spending gap will be positive and GDP will fall as firms realise they are over-producing relative to effective demand. This leads to a spiralling down of output, income and employment, and, ultimately, a recession results.

The budget deficit rises as the economy recesses even if the government leaves its fiscal policy settings unchanged – this is the operation of the automatic stabilisers in force – tax revenue collapses and welfare payments rise.

So if these writers really wanted to educate people about Keynes they would have indicated that the rising saving ratio in the UK meant the budget deficit had to keep rising. The fact that the economy is now in its 5th quarter of recession (deficient aggregate demand) means that the public deficit is not large enough yet to fill the spending gap.

In general, a rising household saving ratio and a fall in consumption is not a reason to endure a recession. We understand clearly from the writings of Keynes and also from the development of MMT that fiscal policy can always be effective to maintain aggregate demand.

There is a debate that can be had about the form of the fiscal intervention – but never about the principle that a rising non-government spending gap requires a rising government budget deficit if you don’t want income losses to occur.

Unfortunately, the dominant ideology seeks at every point to disconnect these ideas. That ideology is continually running smokescreens aiming to convince the uneducated masses that fiscal consolidation is a good thing at the same time they are paying their private debt down and saving more. In general, the two ambitions are contradictory and cannot work. But then the neo-liberals have never really been concerned about public purpose. The scam has always been to redistribute as much national income to the profit elites as possible.

The loanable funds model also underpins the mainstream claims that budget deficits create financial crowding out of private investment. The fallacious line of reasoning is that there is only a finite supply of saving available and by drawing on it the government pushes up interest rates and chokes of investment.

This proposition is asserted in every mainstream macroeconomics textbook in the world and unsuspecting students are brainwashed into believing it is a reliable reflection of the monetary system they live in. It is not! The depiction is not even remotely close!

I read this assessment – Fear and loathing on fiscal comeback trail in today’s (December 24, 2009) Melbourne Age.

The Wall Street consensus is that growth will be about 2.7 per cent next year, roughly a third as robust as it is in normal climbs out of recession, and one fear is that the funding of the federal deficit will bear down on growth, either as taxes and other imposts rise to meet the bill, or as the US Treasury’s demand for debt-servicing funds in the capital market crowds out the private sector.

But once again a failure to understand the monetary operations of the system leads journalists to impose this wrong-headed reasoning on the readers.

We can think of the deficit-debt nexus as a wash as in the US term “Lets call it a wash”. If everyone understood this then there would be a major change in the political debate and most of the so-called expert economics commentators would be out of a job.

Proponents of the logic which automatically links budget deficits to increasing debt issuance and hence rising interest rates fail to understand how interest rates are set and the role that debt issuance plays in the economy. Clearly, the central bank can choose to set and leave the interest rate at 0 per cent, regardless, should that be favourable to the longer maturity investment rates.

There are clearly substantial liquidity impacts from net government positions which I have written about before. If the funds that purchase the bonds come from government spending as the accounting dictates, then any notion that government spending rations finite savings that could be used for private investment is a nonsense.

US financial market commentator and investment advisor Tom Nugent wrote elegantly about this (Source):

One can also see that the fears of rising interest rates in the face of rising budget deficits make little sense when all of the impact of government deficit spending is taken into account, since the supply of treasury securities offered by the federal government is always equal to the newly created funds. The net effect is always a wash, and the interest rate is always that which the Fed votes on. Note that in Japan, with the highest public debt ever recorded, and repeated downgrades, the Japanese government issues treasury bills at .0001%! If deficits really caused high interest rates, Japan would have shut down long ago!

Only transactions between the federal government and the private sector change the cash system balance. Government spending and purchases of government securities (treasury bonds) by the central bank add liquidity and taxation and sales of government securities drain liquidity.

These transactions influence the cash position of the system on a daily basis and on any one day they can result in a system surplus (deficit) due to the outflow of funds from the official sector being above (below) the funds inflow to the official sector.

The system cash position has crucial implications for central bank monetary policy in that it is an important determinant of the use of open market operations (bond purchases and sales) by the central bank.

Government debt does not finance spending but rather serves to maintain reserves such that a particular overnight rate can be defended by the central bank. Accordingly, the concept of debt monetisation is a non sequitur. Once the overnight rate target is set the central bank should only trade government securities if liquidity changes are required to support this target.

So we should shout in from the roofs that in an accounting sense the money that is used to buy bonds (that is allegedly regarded as financing government spending) is the same money (in aggregate) that the government spent. Deficit spending introduces the new funds to buy the newly issued debt.

Conclusion

To sum all this up I thought the New York Times editorial Americans Without Work on December 22, 2009 was apposite (well one paragraph anyway).

You read in one paragraph why the deficit terrorists need to re-think their position. The editorial is about the recent US Jobs Bill which went through Congress last week but will not do much at all to address the unemployment problem.

The paragraph that follows in succint yet insightful (I wish I could write so):

Right now, finding people work is a more urgent task than reducing the deficit. Indeed, deficits cannot be tamed without more jobs to generate more tax revenue. A government boost to job growth is also necessary to help replace the millions of jobs that have been lost in the recession.

So you see if you drop the neo-liberal brainwashing that restricts the way we think about solutions and gain a thorough understanding about the way the monetary system really operates and the essential interactions between the government and non-government sectors then you will realise that:

There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending.

which was the title of a paper I wrote last year with James Juniper. The working paper version is freely available if you are interested and haven’t already read it.

You will not get that insight if you don’t start by understanding the financial and economic flows and stocks that arise from the government and non-government relationship. That has to be the starting point to understanding all the rest of the dynamics that arise within the non-government sector.

Digression: Top Cat voice dies

One of the things that happen as you get older is that things from your childhood come back into prominence, if only briefly, when someone that had some influence in your earlier years, dies.

This happened today when the voice of Top Cat, Arnold Stang died at the age of 91.

Interestingly, there were only 30 Top Cat episodes recorded (in 1961 and 1962). They didn’t reach Australia until the second half of the sixties.

It was a prime-time cartoon in the US which meant it aired during adult viewing hours. It was considered an intelligent show. Which raises the question – in Australia it was shown in the afternoon just after school hours (during children viewing hours) – the question is obvious!

The following links are interesting. The Hawaii here we come episode was representative and consistent with this blog it also has a very neat monetary theme.

I personally like the section when the character “Brain” – was asked by TC – “Are you here Brain?”; the aptly named Brain replies – “I think so, I was just talking to myself”. The life of a researcher has parallels.

I think to expect government dis-saving to off set private (well at least personal) sector savings to increase and thus avoid recession is economically true, but is it desirable?

Surely for those countries that have accumulated large personal sector debt such as the UK, New Zealand, Iceland, Ireland, Spain, Latvia, US, it is desirable that aggregate country balance sheets are re-built? So there is no point in the personal sector improving its balance sheet at the same rate the government is weakening its balance sheet. In aggregate there will be no reduction in overall country indebtedness. For all the hype about consumers paying down debt in the UK and the US, aggregate debt to GDP remains at record highs.

Surely we have to accept that many countries have to rebuild their aggregate balance sheet and that means either:

a) the government and personal sector increasing their savings ratio (or reducing the deficit dramatically) and the accepting a period of retrenchment / recession is inevitable and even desirable in order that debt / gdp is sustainable

or

b) depreciate the real exchange rate in order to steal growth from those countries with savings so that debt / GDP improves via an increase in nominal GDP

Whether countries do a) voluntarily or the foreign exchange markets force b) is the question as to how the over-indebtedness of some western countries will be resolved?

Nic

Dear Bill,

Do you believe that sustained government deficits, no matter how spent, will pull the economy out of recession and back into growth? Are there reasons the spending (if all done with matching sales of government bonds) could not create growth and that the interest on the debt could then consume an ever-increasing portion of the tax revenue?

Is the £200 billion of Quantitative Easing not what you ask for? The Bank of England has created £200 billion of new money and bought £200 billion of Government Bonds. Is this not funding the deficit with new money? Everyone keeps discussing QE in terms of its effect on reserves but I can’t help thinking that it is in fact a method to fun the deficit with new money! If the cash replaces the bonds then the Govt has replaced a liability with no liability at no cost to itself!

I have posted a number of questions on your previous ‘Business Card’ post. My understanding of Economics is not great but I am striving to better it so anything you can do to help is appreciated!

All the best,

Alex

Hi Alex,

Let me answer some of your questions. Maybe you can pick up and (re)read some posts. I picked up a line from Warren Mosler and going to use it here “The Federal Government doesn’t ever ‘have’ or ‘not have’ any dollars”.

Money should be looked at as a balance sheet entry. Bank deposits are sit on the Assets side of the holder and on the Liabilities of the bank. Banks have accounts at the central bank. Banks are said to hold reserves with the central bank – assets for banks, liability for the central bank.

When a government spends, it credits bank accounts and increases bank reserves. The private sector assets increase because of government spending! Banks cannot lend the reserves to me or you. Banks lend by just increasing your deposits with them. Quantitative easing is based upon looking at money as a commodity and the central bank thinking “we give money to banks in exchange for bonds and they will give this money to the people” – totally wrong if you think about it.

As mentioned in the first para, governments cannot run out of money. So important things to look at are full employment and price stability. Right now the situation is that people want to save more rather than consume – the government thus has to spend a lot and just keep spending till the private sector is satisfied with their saving and decide to start spending more. In this process, it would have created a lot of employment and there is no fear of price rise! The relation between M2/M3 and prices is weak. Many countries are in recession because the governments went into fiscal austerity.

It is easy to confuse government spending and the central bank operations. The latter (note the use of spending and operations) just exchange one private sector asset for another which is not of much help.