The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Germany’s sectoral decline and its obsession with fiscal austerity

I am currently researching statistical and textual material as part of my plan to produce an updated version of my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – to take into account the pandemic, Brexit and other major changes that impact on Europe’s position in the world economy and the internal shifts within Europe itself that will make it even more difficult for the Member State nations to maintain their material living standards. My publisher (Edward Elgar) is keen to push this project on. As part of this work I have been examining changes since 2015 across various European states. Today, I discuss the decline in Germany’s fortunes that has arisen as a result of a combination of circumstances: an obsession with fiscal austerity; the suppression of domestic spending capacity; the unrelenting promotion of the so-called ‘export-reliant, manufacturing-heavy economic model’; the election of Donald Trump; and the maturing of the Chinese economy. German politicians, particularly, have become so caught up in the ‘Schwarze Null’ ideology that they have failed to anticipate the medium- and longer-term consequences of their actions. These consequences were all laid out in my 2015 book but policy makers have generally ignored any criticisms of the ‘German model’. Now the chickens are coming home to roost. Fast. And it spells bad times for Europe.

The theme in my 2015 book was captured by the title – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – and it traced the evolution of the attempts by the European nations to create an economic union, which culminated in the decision in 1992 when the – Maastricht Treaty – was signed by 12 Member States of the EU, to enter a common currency.

That decision created a monetary architecture that is dysfunctional and relied on the ECB to breach its strict treaty restrictions in order for several nations to remain solvent in the face of various economic crises since the currency became operational on January 1, 1999 (and then finally replacing the old currencies on January 1, 2002).

I have written extensively about Germany’s position in the Eurozone over the years, including this selection of blog posts:

1. Germany continues to kill the Eurozone (August 22, 2024).

2. The Merkel failure (September 27, 2021).

3. German external investment model a failure (August 19, 2019).

4. Germany is now suffering from the illogical nature of its own behaviour (August 13, 2019).

5. German growth strategy falters – exposes deep flaws in the EU architecture (February 19, 2019).

6. EU deliberately subjugates prosperity to maintain its neoliberal ideology (January 17, 2019).

7. Germany – a most dangerous and ridiculous nation (December 27, 2017).

8. German trade surpluses demonstrate the failure of the Eurozone (April 24, 2017).

9. Germany should look at itself in the mirror (June 17, 2015).

10. Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home (March 2, 2015).

11. The stupidity of the German ideology will come back to haunt them (September 2, 2013).

12. The German model is not workable for the Eurozone (February 3, 2012).

The message was clear.

Upon entering the Eurozone and losing the ability to influence its external trade competitiveness by manipulating the Deutschmark exchange rate, Germany embarked on a massive internal devaluation via the so-called Hartz reforms, which created millions of poorly paid (Mini Jobs) and undermined real wages growth generally.

Germany knew that this would give it an advantage over other Eurozone nations and allow it to maintain its export dominance, which in no small part has been based in its motor vehicle manufacturing sector.

The increasing German export surpluses, of course, had their expression in the chronic trade deficits of other European nations, which created unsustainable external imbalances across the Eurozone.

With the austerity imposed on Germany’s main trading partners within the Eurozone, German industrialists thought they had a winning strategy by diversifying their export market to take advantage of the rapid growth of China.

Except! (see below).

Further, by suppressing domestic demand, the trade surpluses then had to find rates of return elsewhere and so German capital started to invest in construction and other developments throughout Europe which spawned a massive real estate boom that collapsed during the GFC.

Debt was cheap throughout Europe as well because the ECB was setting interest rates at low levels to deal with the German recession early in the common currency.

Other nations, particularly those in the South did not experience the recession and it is arguable that the uniform low interest rates were inappropriate for their particular situations.

This was just another problem with the common currency architecture, which tried to set policies for many nations that were disparate in industry structure, export strength and material living standards.

Further, as the largest economy in Europe, fluctuations in German economic fortune, had major effects on the other Member States through the trade linkages.

The blog posts cited above trace the way in which Germany’s obsession with fiscal surpluses and reducing government debt, coupled with its suppression of domestic spending capacity (through the real wage suppression etc), was slowly undermining the viability of the common currency, but also steadily undermining its own economic model.

In recent years, it is becoming clear that the German industrial powerhouse is now compromised after years of poor government policy and hubris among the industrial leaders.

The following graphs show what has been going on in the German economy since the March-quarter 1991 (up to the September-quarter 2024).

They tell quite a story.

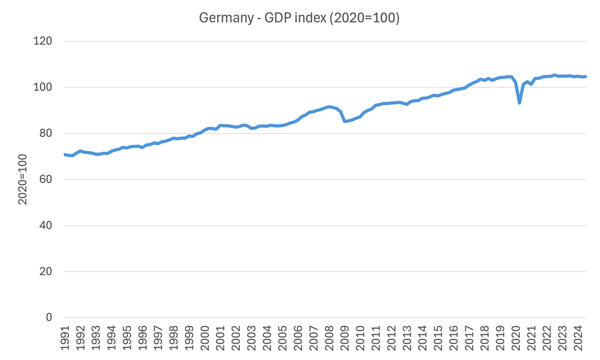

First, GDP growth has been modest and has been trending down since the 2019 (the pandemic was an interruption to this trend).

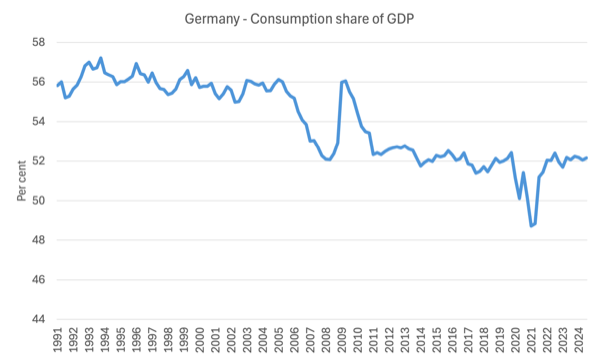

The next graphs show the expenditure shares in total GDP.

Household consumption expenditure started slumping with the austerity in the convergence period of the 1990s and then tanked with the Hartz changes.

It has found a new much lower level since.

Total investment expenditure followed a similar path.

Overall, domestic demand as a share of GDP has fallen quite significantly over the period shown.

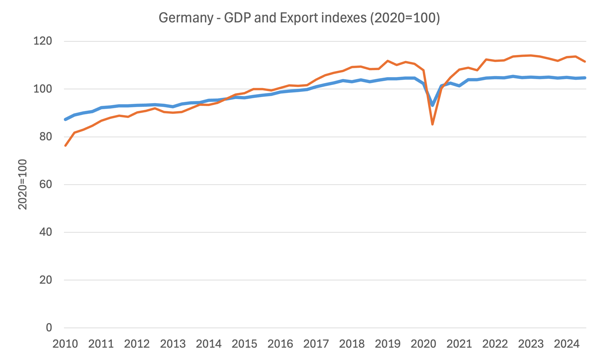

The trajectory of net exports is interesting.

After booming during the early period of the common currency (with the aid of the Hartz suppression of real wages etc), the share has been in decline since 2015, which is one of the main reasons GDP growth has stalled since around that period, given the flat domestic demand.

The next graph shows how export growth (the higher line) has driven German growth (lower line) since the GFC.

For years, the mainstream commentariat has held Germany out as the exemplar of economic policy and industrial strategy.

But for me, it was clear (as the above blog posts indicate) that it was only a matter of time before the ‘miracle’, the ‘Jobs Wunder’ or whatever else the German economy has been called, would stagnate and that stagnation will set off a process of further decline for Europe.

It seems that even the mainstream press is now waking up.

There was, for example, a recent article in the Wall Street Journal (January 26, 2025) – Germany’s Economic Model Is Broken, and No One Has a Plan B – documents the decline of Germany that has followed poor policy interventions and short-sighted entrepreneurial behaviour.

It relates how the motor vehicle sector has been an important contributor to the tax bases of local city where they are located.

However, with the major German manufacturing companies now reporting massive declines in profits and implementing major job cuts, that largesse is disappearing fast.

The WSJ reports that:

Audi’s business in China, where Germany’s flagship car industry used to make a big chunk of its sales and an even bigger chunk of profits, shrank by a quarter in the nine months through September from a year earlier. Chinese carmakers, once mocked by Western auto executives as primitive, have turned into formidable rivals, gobbling up market share in and outside China.

And, the reliance on Chinese growth is now problematic as:

Slowing economic growth in China and growing competition from companies there have undercut German industry as a whole.

China is entering a new phase in its own economic development where lower growth rates and more reliance on the growth in domestic demand and consumption is evolving.

That spells danger for Germany’s car manufacturers who are now contracting fast.

The upshot:

German carmakers and their suppliers have announced tens of thousands of job cuts. Germany’s manufacturing industry, the world’s third largest, has shrunk steadily for seven years. And Germany’s economy as a whole has contracted for the past two years, marking only the second back-to-back annual contraction in records dating back to 1951, according to Germany’s federal statistics agency.

The WSJ also suggests that the election of Donald Trump and his tariff strategy has closed the US “relief valve” for German manufactures.

The Hartz years, which the WSJ says held “down business costs … boosting exporters’ international competitiveness, paving the way for two decades of solid growth” – which defined “Germany’s export-reliant economic model” is now looking like a trap for Germany and leading it into sectoral decline.

The German polity has their heads buried in the sand and are facing the surge in AfD which has compromised the major traditional political parties to the point that Germany’s recent government has collapsed.

The WSJ says that the engineering and manufacturing boom is over as:

… the world is turning its back on made-in-Germany, and Germany has no plan B.

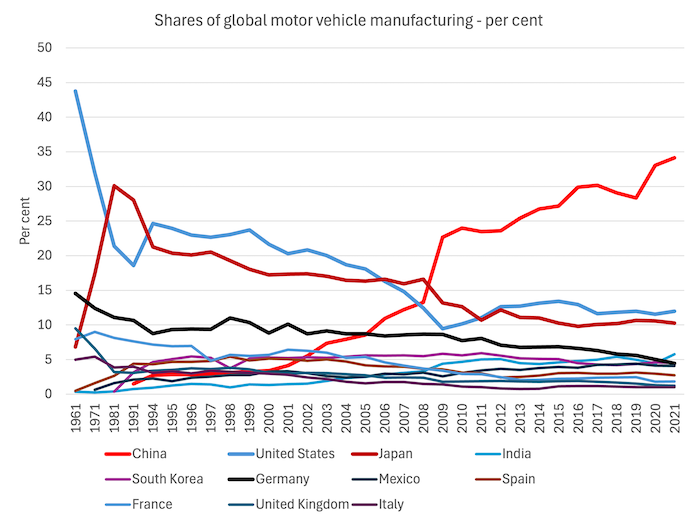

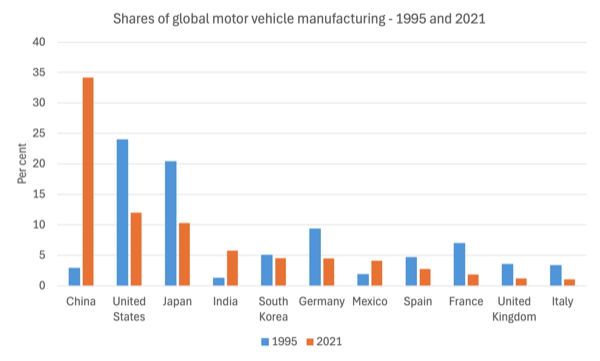

The following graph captures the dramatic shift in the global motor vehicle manufacturing sector since the turn of the century.

It shows the national shares in global motor vehicle manufacturing since 1961.

Note the first four observations are 1961, 1971, 1981, and 1991, then the data becomes annual after 1994.

The shift is quite startling with the former dominant nations (the US, Japan and Germany) slipping in importance and China becoming the dominant nation on its own since around 2008.

The acceleration in China’s position during the global financial crisis years is quite amazing.

Another way of looking at this is to compare the top 11 manufacturers in 2021 in terms of the shifting proportions since 1995.

The graph also provides some detail that helps to understand all the movement below the big four in the previous graph.

Economists in Germany claim there is no “new economic model” being developed to replace the “current export-reliant, manufacturing-heavy economic model”.

Huge employment losses in manufacturing are forecast.

Partly that will arise because German manufacturers will probably respond to the US tariffs by shifting production to the US.

So capital will probably be able to insulate their profits somewhat while German workers take a further hit.

But with the rising dominance of China in the manufacturing sector, even the capacity of capital to defend profits is in doubt.

The export sector manufacturing sector in Germany “supports one in four German jobs” directly in assembly plants and through the network of component suppliers and indirectly through the expenditure multiplier process.

The decline of that sector exposes the failure to nurture domestic demand.

The WSJ notes that the response of local authorities who are facing a severe shortfall in tax revenue has been to impose austerity on citizens:

… jacked up fees for museums, parking spaces and buses, and ordered that public lawns be mowed less frequently … considering raising property taxes and cutting spending further.

So the peril increases.

All sorts of local sponsorships are now being abandoned (sports clubs, cultural events) and the negative multiplier effects are devastating local trades (for example, building) and service businesses (restaurants etc).

The other issue is the impact of climate change with energy costs rising for manufacturers in Germany.

And, finally, the mainstream media is recognising that:

Decades of government underinvestment have left Germany with a depleted transportation infrastructure, including trains that no longer run on time and a military that is a shadow of what it was during the Cold War. In May, the business-affiliated IW economic institute and the trade union-owned IMK think tank estimated Germany would need €600 billion in spending over the next 10 years to offset its investment gap, modernize the country’s education system, fix its transport networks, upgrade its power grid and digitize its public administration.

The chickens are on their way home fast.

The obsession with austerity – the ‘Schwarze Null’ (Wolfgang Schäuble’s baby) – has left a huge accumulated ‘spending gap’ on essential infrastructure.

See this blog post – Die schwarze Null continues to haunt Europe (May 21, 2018) – for more discussion on that obsession.

Government typically can get away with the political consequences of austerity by attacking capital investment rather than recurrent spending because the manifestations take longer to become visible.

Cutting a pension is immediate.

Cutting maintenance on bridges is not.

But eventually the bridges become dangerous and then the political fallout becomes real.

Germany is now at that point after years of government neglect.

While Wolfgang Schäuble was boasting about the prudence of Germany’s austerity the bridges and railways and the rest were slowly falling apart.

The other problem is that German households have responded to the austerity by increasing their saving rate (“Germans are also saving 20% of their income as of the second quarter of 2024, more than the eurozone average and a near two-percentage-point rise since just before the pandemic.”)

And with “constitutional restrictions on government spending and public debt” how will the spending gap be overcome as exports slide.

Conclusion

With climate change likely to devastate the agricultural capacity of Southern Europe and Germany in sectoral decline, the future for Europe is grim.

It is hard to see the common currency surviving without massive changes to the monetary architecture.

But then I suggested that would be the case in my 2015 book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Perhaps they’ll try the ‘crumbs from the table’ model the Irish are using.

Invite in a load of foreign operations, who own monopolies due to the overly rigid and extensive Intellectual Property laws across the world, into Ireland, where they extract rents from the rest of the fixed currency area. Then skim a very small percentage off the top in corporate and social taxation.

The result is an accounting surplus which gets the leaders of Ireland plaudits from know nothings, but most importantly their tummies tickled in Brussels.

The Dublin elite are over the moon, and everybody else can go whistle.

The EU decline is getting evident by the hour.

Yanis Varoufakis said that the EU would become a failure if it didn’t democratize itself until 2025.

Well, it’s 2025 and guess what?…

The US and Russia are talking about peace in Ukraine, leaving the EU to the role it chose to have: vassals of the biden administration, which is now beeing accused of fraud, with a gap of 123 billion dollars, between what they said they have given to Ukraine and what Zelensky says they got from the US (77 B$).

Lets not forget the genius Ursula van der Leyen, who said the Russians were desoldering chips from washing machines to make drones. How’s that for deception?

How can these yellow minions dare to speak about Ukraine, when Ukraine counts 1 million dead in a war they couldn’t win?

Take not my word for it: it’s precisely what the US Secretary of State, Mark Rubio, said about the war.

And yet, we see these people, which nobody elected, talking about the need for the EU to participate in the peace talks.

What for? What did they do to end the war? Feeding the Ukrainian elites with money so that the killing could continue?

Or maybe not. Maybe the millions were gone to the same place that the biden administration sent the 123 B$. Maybe they’ll say they were for peace all along… Lets desolder some chips.

How does peering through an MMT lens help us see the way toward de-growth (reduced total energy consumption)?

The US “disciplining” Germany (and thereby putting the frighteners on the rest of the EU) through shutting off Russian gas in blowing up NS2 under a poorly disguised false flag attack that was soon exposed. That removal of cheap Russian energy was necessarily going to result in a diminution of the competitiveness of German industry through the purchase of higher priced US gas after even more expenditure on facilities in Germany to receive the gas. In that energy expended = GDP, the outcome was preordained.

A dead-handed attempt by the US to coerce important German manufactures to relocate to the USA. A clear demonstration how the captured German political hierarchy are well and truly under the control of those in charge of the US. Meanwhile China is making hay while the sun shines. The automotive industry just being a case in point, already aided and abetted by Germany being far too slow to convert from ICE automobiles to EVs to compete with the vehicles coming out of China.

The corporate mainstream media (propaganda arm of capital controlled governments) hasn’t portrayed the behind the scenes goings on that have caused the diminution of German manufacturing. It is from the likes of Michael Hudson that the actions and consequences become clear. Vassalisation of Europe becomes ever more visible. I’ve heard said that EU politicians are some of the least expensive purchases for the US.

As one wag put it, the “schwarze null” and its associated failure to invest in public infrastructure has meant that Germans collectively chose to live in a dumpster rather than take out a mortgage …

Apparently, however, a large majority of

Germans (including the FDP voters!) are in favour of more public investment, even if this means increasing government debt. Interesting to see how this dynamic plays out in the coming election and beyond.

https://newforum.org/en/survey-germans-in-favour-of-government-debt-to-finance-investments/#msdynttrid=k4T10HGRCT5ZHwkLPiY1fFt7r-KVj86JtCkFpaUIK6s

France and Germany are ungovernable due to their persistence i neocon neoliberal BUllsh$t!

We should talk about how aging populations and pension savings, sometimes legislatively forced savings create constant demand for new government issued money in our economies. It’s a tug of war situation in many countries whether pension savings pull economy into recession or not.

John B., see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800923002318.

“Degrowth lacks a theory of how the state can finance ambitious social-ecological policies and public provisioning systems while maintaining macroeconomic stability during a reduction of economic activity. Addressing this question, we present a synthesis of degrowth scholarship and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) rooted in their shared understanding of money as a public good and their common opposition to artificial scarcity. We present two arguments. First, we draw on MMT to argue that states with sufficient monetary sovereignty face no obstacle to funding the policies necessary for a just and sustainable degrowth transition. Increased public spending neither requires nor implies GDP growth. Second, we draw on degrowth research to bring MMT in line with ecological reality. MMT posits that fiscal spending is limited only by inflation, and thus the productive capacity of the economy. We argue that efforts to deal with this constraint must also pay attention to social and ecological limits. Based on this synthesis we propose a set of monetary and fiscal policies suitable for a stable degrowth transition, including a stronger regulation of private finance, tax reforms, price controls, public provisioning systems and an emancipatory job guarantee. This approach can support broad democratic mobilization for a degrowth transition.”