In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

ECB should take over and repay all the joint debt held by the European Commission after the pandemic

There are repeating episodes in world macroeconomics that demonstrate the absurdity of the mainstream way of thinking. One, obviously is the recurring debt ceiling charade in the US, where over a period of months, the various parties make threats and pretend they will close the government down by failing to pass the bill. Others think up what they think are ingenious solutions (like the so-called trillion dollar coin), which just gives the stupidity oxygen. Another example is the European Union ‘budget’ deliberations which involve excruciating, drawn out negotiations, which are now in train in Europe. One of the controversial bargaining aspects as the Member States negotiate a new 7-year deal is the rather significant quantity of joint EU debt that was issued during the pandemic to help nations through the crisis. How that is repaid is causing grief and leading to rather ridiculous suggestions of further austerity cuts and more. My suggestion to cut through all this nonsense is that the ECB takes over the debt and insulates the Member States from repayment. After all, the debt wasn’t issued because the Member States were pursuing irresponsible and profligate fiscal strategies.

The debate in Europe is almost parallel to reality.

First, some context.

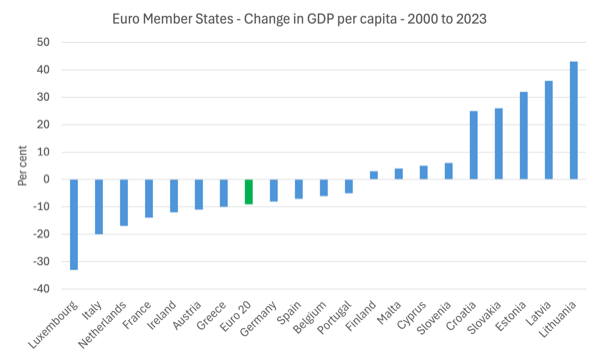

The following graph shows the percentage change in real GDP per capita in the Euro 20 Member States as well as the overall aggregate (in green) from 2000 to 2023 (latest data from Eurostat).

The majority of Member States are on average poorer in this respect, some significantly so.

The overall common currency area declined by 9 per cent over the period that the Euro has been in use (up to 2023).

When this data is available for 2024, the situation will have worsened a little, given the more recent national account figures.

I could assemble many indicators that would reinforce the conclusion that in economic terms, the adoption of the common currency has been disastrous for many nations, including the larger traditional EU Member States such as France and Germany.

The old Baltic satellites have fared better than those traditional EU states but they were coming off a very low base.

Second, remember Mario Draghi’s speech at CEPR on December 18, 2024 – Policy Insight 137: Europe: Back to Domestic Growth – where he did everything but admit that the architecture of the monetary union was dysfunctional.

He opened that address with this:

Productivity, incomes, consumption, and investment have been structurally weak in Europe since the turn of the millennium and have significantly diverged from the US.

It was not always this way. After the second world war, Europe’s labour productivity converged from 22% of the US level in 1945 to 95% in 1995. And for most of this period, domestic demand as share of GDP in the euro area stood in the middle of the range of advanced economies.

He then claimed that the technology shock (Internet) and the GFC meant that from the “mid-1990s onwards, relative growth in the US and euro area was pushed apart”.

He declined to mention a larger reality in the mid-1990s.

That the signatories to the Treaty of Maastricht had begun their so-called convergence process to ensure they could be included in Stage 3 of the Treaty introduction (the shift to the euro).

That convergence process saw these nations begin the austerity push which largely set in motion the stagnation that has followed.

Draghi tried to claim the GFC was somehow instrumental in creating a divergence between the US and the Euro area in terms of material prosperity:

… the great financial crisis and sovereign debt crisis, following which the orientation of the euro area shifted away from domestic demand.

This is true.

But why did the Euro area suffer a sovereign debt crisis and impose austerity when the US and other advanced countries avoided such turmoil?

The answer lies in the flawed monetary architecture that the neoliberals led by Jacques Delors foisted on the Member States which not only saw them surrender their currency sovereignty in favour of using a foreign currency (the euro) – the source of the sovereign debt crisis – but also coerced them into accepting fiscal rules that meant they did not have sufficient flexibility to defend domestic demand and economic activity against negative cyclical shocks.

And, moreover, the enforcement of the fiscal rules through the – Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) – by the technocrats in the European Commission, aided and abetted by the ECB and the IMF, meant that the capacity to produce income growth was decimated.

The GFC was as the name suggests ‘global’ in impact.

But it was the Europeans and other nations that insisted on imposing such austerity as the automatic stabilisers drove up deficits (as non-government spending declined and unemployment rose) increased.

The European economies signed up to that destructive response and have never really recovered since.

Draghi understands clearly the situation:

With investment stalling and fiscal policy becoming contractionary, both the corporate and government sectors shifted to being in surplus. As a result, domestic demand as a share of GDP in the euro area fell to bottom of the range of advanced economies …

The relative stance of fiscal policy was an important driver. From 2009 to 2019, the collective cyclically-adjusted fiscal stance in the euro area averaged 0.3%, compared with -3.9% in the US.

Bank loans also dried up in the Euro area between 2009 and 2016 because the demand for credit dried up.

The ECB claimed the lack of bank lending was because they didn’t have sufficient reserves and embarked on a QE program.

But it was never about a lack of reserves and all about lack of confidence.

Draghi also had a veiled shot at Germany in his speech:

Moreover, European policies tolerated low wage growth as a means to increase external competitiveness, compounding the weak income-consumption cycle. Since 2008, annual average real wage growth has been almost four times higher in the US than the euro area.

The leader in the ‘low-wage charge’ was Germany, who via the Hartz attacks on labour market conditions, thought they were being clever by gaming the other Member States and ensuring their export sector would boom.

Please read my recent blog post – Germany’s sectoral decline and its obsession with fiscal austerity (February 3, 2025) – for more discussion on where that strategy has landed Germany.

Draghi recognised that the policy model deployed within Europe that suppressed domestic demand via fiscal austerity and low-wages and sought growth via export markets (particularly China) is “no longer appears sustainable”:

For some time now, the Chinese market has been become less favourable for European producers as growth slows and local operators become more competitive and move up the value chain. Exports to China have stagnated since 2020.

The problem is that the ideological mindset of the European polity and the macroeconomic policies that they envisage are not:

… well placed to fill the gap left by external demand.

That summary really amounts to a devastating critique of the whole structure of the monetary union, of which Draghi was a central figure in enforcing.

Of relevance to the next part of this discussion is the fact that Draghi realises that:

If the EU were to issue debt jointly, it could create additional fiscal space that could be used to limit periods of below-potential growth …

If EU bonds traded like equivalent safe assets today, the convenience yield would push borrowing costs below growth rates.

This differential would allow the EU to issue additional debt – potentially up to 15% of GDP – and roll it over indefinitely without requiring payments from the Member States.

In other words, Europe should abandon the notion that the major counter-cyclical macroeconomic policy capacity should remain at the Member State level, which are constrained by the fact that their debt is subject to credit risk (because they are issuing debt in a currency foreign to them) and the fiscal rule monitors are watching them like hawks ready to shunt them into the EDP and force austerity cuts on their governments.

In my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – I argued that the way out for Europe was to create a true federation which a federal fiscal capacity that would dominate the Member State policy capacity in financial terms.

That option was deliberately eschewed by the founders because they knew Germany, for one, would never sign up to it and they also desired to limit the capacity of national governments – they were neoliberals after all.

The concept of EU joint debt or debt issued by the European Commission rather than the Member States is now dominating the current discussions about the next EU ‘budget’.

Politico carried a story earlier this week (February 11, 2025) – The EU’s ticking debt bomb — and why it matters for its next budget – which captures the European mentality in the headline.

“Ticking debt bomb”.

A friend sent me the link with the E-mail heading ‘Ticking’.

I laughed.

The EU Member States are embarking on the torturous process of designing the next 7-year fiscal policy (budget) with a rather substantial pandemic hangover in the form of the joint debt that has to be repaid from 2028 (the budget period runs from 2028 to 2034).

Nothing is quick in the EU.

Politico notes that:

Deliberations are even more difficult this time around because the Commission’s €300 billion joint debt program to rescue the EU economy after the Covid pandemic is up for repayment from 2028. Without a new plan, that could take a huge chunk — between 15 percent and 20 percent, according to the Commission’s estimates — out of the bloc’s spending power.

So designing a “repayment plan before 2028” is occupying the technocrats and politicians.

The four most exposed nations face significant ‘worst-case’ contribution scenarios – Germany (€35.8 billion), France (€28.6 billion), Italy (€19.6 billion), and Spain (€13.4 billion).

All these economies are in decline and some might say structurally so.

The first Commissions strategy was to use “levies on carbon emissions, imports and profits of multinationals” to repay the debt but that was rejected by the Member States because it would have diverted a vital source of revenue for themselves.

The reality is that:

The default option consists of national governments filling the hole by sending more money to Brussels.

But that is highly problematic given the fiscal rules and the lack of solidarity within the so-called Union.

Politico notes that:

Countries from Northern Europe — which have received a relatively small share of the EU’s post-Covid aid — are loath to pay more into the budget …

Which goes to the heart of the problem of the architecture.

The on-going hostility of the rich Northern Member States to making unconditional transfers within the Union to help other Member States deal with asymmetric shocks and poor economic performance is why the monetary union should never have been created in the first place.

Member States within functional federations (say Australia) know that the federal fiscal capacity has to be able to make asymmetric fiscal transfers when the need arises.

Just this morning, the Australian government announced a large fiscal package that will help Northern Queensland deal with the recent major flooding episode that has devastated regions and town in that part of the nation.

No-one in the Southern States blinks and demands payment in return.

But the Northern European states are arguing they want cuts to assistance to other states within the Union if they are forced to contribute to paying off the Covid debt.

They clearly do not see a ‘federal’ system and are suspicious of the Southern Member States.

Which is one of the reasons the dysfunctional architecture was installed in the first place – Germany publicly stated its mistrust of Italian officials, for example.

In fact, during the late 1990s convergence process, German officials argued that Italy should be excluded from Stage 3 because its public debt to GDP ratio was too high (outside the SGP parameters).

It was only when it was pointed out that Belgium, was in a similar situation, that the Germans realised that tack wouldn’t work.

Politico reports that:

But Germany and its fiscally conservative allies see this as a slippery slope toward a fiscal union, in which the Commission permanently takes on the debts of its 27 members.

And Germany will never allow that to happen.

Here is my suggestion with the current design parameters of the system (noting I advocate abandoning the whole common currency):

1. The responsibility for the joint debt be taken off the European Commission and handed over to the ECB. That could easily be done.

2. The ECB then pays the debt off when payments fall due with a stroke of a computer keyboard. It is the currency issuer and has infinity minus one euro penny capacity to do this.

3. No liability or conditionality would be imposed on the Member States.

No fiscal crisis.

No austerity necessary when the opposite (as Draghi notes) is required.

QED.

Critics would claim this approach would just fuel so-called moral hazard and encourage the Member States to spend up big and issue stacks of debt.

First, they cannot under the fiscal rules ‘spend up big’.

Second, the bond market yields would rise before they could issue ‘stacks of debt’.

Third, and more importantly, the joint debt that is causing all the controversy and heartache was not issued as a result of fiscal profligacy by the Member States.

Nations around the world were facing a pandemic, which we had no real understanding of and no certainty of what was going to happen.

Governments had to act in a significant manner to provide some surety to their citizens in such an uncertain period.

So the European officials could easily make the case that this joint debt was something quite different (which it was) relative to national government debt issued to cover fiscal deficits that are, in part, the product of discretionary fiscal decisions they have taken (good or bad, prudent or irresponsible).

Conclusion

Such an immediate and simple solution is too obvious for the tortured souls in the European Commission.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The EU is a failure.

There is no european identity.

Germans don’t feels europeans: they feel Germans.

The same with the French, the Spanish, Italians, everyone!

It’s not even a question of jingoísm, like what the far-right is trying to revive (to their advantage, of course, and the oligarchs that bankroll them – can anyone see muskie bankrolling the German AfD? Anyone?…).

The question is that the blob remains a sum of individual countries, impossible to organize in a coherent orchestra.

Everything is biased by the power that individual countries get in the overall power play.

What was supposed to be a country or a federation of countries is a colonial system with an imperial master and vassal states all around it.

With a dwindling industrial capacity, all it will sell in a few years time are services, which no one needs.

Many countries are already limited to the one industry that survives colapse: tourism.

Just like 3rd world countries.

I believe that the EU colpased long ago. Maybe we could point a date to the colapse.

I would bet in the day that the UK left the blob, but maybe the Ukraine war could be a good candidate too.

Fiat currency spending preserves and protects the very system that causes the harm that the spending attempts to ameliorate.

Capitalism’s externalities are distorted and obscured by the MMT lens. Viewed through a clear lens, capitalism is responsible for the harm it causes. Through the MMT lens, the state is made to appear responsible. It was to shift responsibility for capitalism’s harms to the state that the link between currency and gold had to be broken, and the MMT lens invented.

Externalities are the responsibility of capitalists who generate them, not of the state. Making externalities generated by capitalism the responsibility of the state shields capitalism from fate. (What fee is enough for destruction of our Earth?)

MMT, even if its lens is used only implicitly (through deficit spending), will be viewed by history as the offspring of the fiat currency system that was designed to postpone capitalism’s reckoning.

I have to disagree with John B as I see that it is the responsibility of the state. The state (government + military-national security controllers) is all powerful and Big Capital is permitted to do what it does (acquire assets from those without capital by whatever means the state allows) only through the power and authority of the state. The state has been captured by capital and that puppeteer pulls its strings to implement and enforce the rules that capital believes suits its purpose – this is where we are today.

Descriptive MMT, ipso facto, reveals the power of the state which is what capital seeks to hide from the hoi polloi to avoid revolution while it gets on with business. Or in the words of that deceased fascist Henry Ford “It is well enough that people of the nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning.”

Another way of seeing what is permitted is to understand that it is a dynamic system which humans have implemented where structure determines behaviour within the bounds of (the worst of?) our collective nature (fear & greed).