The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home

Some time ago I wrote a blog – The German model is not workable for the Eurozone (February 3, 2012) where I outlined why Germany’s export-led growth strategy could not be a viable model for the rest of the Eurozone nations. More recent data shows that Germany is not even working very well in terms of advancing the prosperity of its own citizens. A recent report (in German) – Der Paritätische Gesamtverband (HG): Die zerklüftete Republik (The Fragmented Republic) – shows that poverty rates are rising in Germany and there is now a dislocation emerging between unemployment and growth and poverty rates. The reason is clear – too much neo-liberal labour market deregulation and ridiculously tight fiscal policy. Both failing policies that Germany continues to insist should be adopted throughout Europe. It would do the other Member States a service if they banded together and rejected the ‘German poverty model’.

In the early 1980s, Germany embraced the growing neo-liberal myth that the alleviation of poverty was a participatory enterprise – that the poor had to develop their own productive capacities to get themselves out of their situation. That the Government could do very little.

The German Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ) (the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) set up a national task force to develop the concept that individuals had to take responsibility for their own poverty fight before external help would be forthcoming.

The BMZ was influential in OECD and World Bank policy shifts in this regard. It has also been a major player in the – United Nation’s Millennium Declaration – in 2000 and the subsequent – Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – which have defined the global fight against poverty since 2001.

For reference to the BMZ approach, see their 2010 document – The Millennium Development Goals: Background – Progress – Activities BMZ Information

At the time of writing, there were 303 days, 9 hours, and 36 minutes (and some seconds) to go before the end of 2015 when the 189 nations that signed up to the Declaration will conclude whether they have been the Eight MDG targets.

None will go close!

The Germans are heading in the wrong direction.

In its 2012 Special Paper 146, the BMZ is long on rhetoric – “Pro-Poor Growth” a focal point of development policy – claiming that a:

Pro-poor growth (PPG) is a strategic approach whereby economic growth is specifically used to reduce poverty. The focus is on promoting the economic potential of (extremely) poor and disadvantaged people.

We learn that:

The primary target group of PPG projects is the (extremely) poor and disadvantaged people who can be integrated into the growth process by enabling them to engage in productive employment and entrepreneurial activities … A decisive factor for income distribution and for broad-based participation in economic growth is that as many people as possible have access to productive employment.

The German government has done exactly the opposite to what its key developmental agency advocates.

The organisation – Social Watch – which is dedicated to eradicating poverty and achieving gender justice, wrote in 2002 that the BMZ was more about – AntiPoverty Rhetoric: More Programme than Action – when it came to achieving the MDG targets.

Its most recent report on Germany poverty reduction efforts (2010) – Neglecting the poor and the environment – concluded that real wage cuts associated with the GFC and the expansion of part-time work has seen a rise in poverty rates.

A 2009 – IAQ Report – 2009-05 – from the Institut Arbeit und Qualifikation (Institute for Work, Skills and Training) located at the University of Duisburg-Essen – – found that:

1. The average real wage in the low-wage sector had not increased since 1995 and in recent years declined in the West German regions.

2. The number of low-wage workers rose by 350,000 between 2006 and 2007, comprising around 21.5 per cent of the total wage earners in Germany. In 1995, this share was well below 15 per cent.

3. More than 20 per cent of workers are now working at hourly rates which are below the minimum wage.

4. A declining percentage of workers without formal educational qualifications now make up the low-pay workforce. In other words, formal education is now longer a guarantee (as it was in the past) of a well-paid job in Germany.

All this is not surprising. As I have documented in the past, Germany took a particular route to Eurozone leadership in the early years after the common currency was introduced.

In my soon to be – published book – on the Eurozone, I devoted a chapter to the German Jobwunder!

Once the common currency emerged and Germany lost the ability to manipulate its exchange rate to its advantage (forget the rest), the next strategy it employed was to attack its own workers.

A reasonable argument can be made that Gerhard Schröder helped cause the Eurozone crisis. His government’s response to the restrictions that Germany encountered on entering the EMU are certainly part of the story and one of the least focused upon aspects.

Upon entering the EMU, Schröder was under immense political pressure to do something about the high unemployment in the East after reunification.

Without the capacity to manipulate the exchange rate, the Germans understood that they had to reduce domestic production costs and inflation rates relative to other nations, in order to retain competitiveness.

The Germans thus took the so-called ‘internal devaluation’ route that is all the rage in Europe now, well before the crisis; a move, which ultimately has made the crisis worse.

When Schröder unveiled his Government’s ‘Agenda 2010’ in 2003, it was clear that they were going to income support systems and ensure that Germany’s export competitiveness endured despite abandoning its exchange rate flexibility.

It was dressed up in the language of flexibility and incentive, but was based on the mainstream view that mass unemployment was the result of a workforce rendered lazy by the welfare system, rather than the more obvious alternative, that it arose due to a shortage of jobs.

The so-called ‘Hartz reforms’ were a major plank of the strategy and resulted from a 2002 commission of enquiry, presided over by and named after Peter Hartz, a key Volkswagen executive.

The aim was clear, unemployment benefits had to be cut and job protections had to go. The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schröder government and introduced in four tranches: Hartz I to IV, starting in January 2003.

The changes associated with Hartz I to Hartz III, took place over 2003 and 2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005.

The changes were far reaching in terms of the existing labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The so-called supply-side focus saw unemployment as an individual problem and advocated that continued income support should be conditional on a raft of increasingly onerous activity tests and training schemes.

Further, governments abandoned their responsibility to reduce unemployment with properly targeted job creation schemes.

Public employment agencies were privatised spawning a new private sector ‘industry’ – the management of the unemployed!

The Hartz reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market and the precariousness of work increased. Hartz II introduced new types of employment, the ‘mini-job’ and the ‘midi-job’ and there was a sharp fall in regular employment as a consequence.

Mini-jobs provide marginal employment with no security or entitlements and allow workers to earn up to 450 euros per month without paying taxes, while the on-costs for employers are significantly lower. The no tax obligations also mean that the worker receives no social security protection or pension entitlements.

The neo-liberal interpretation of these changes is that Germany underwent a ‘jobwunder’, or jobs miracle.

However the speedy increase in employment can also be viewed less optimistically.

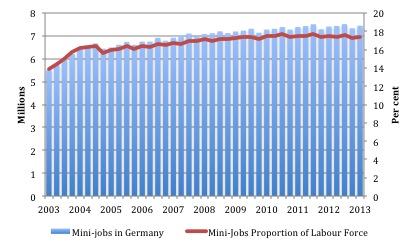

The following graph charts the history of the mini-jobs since 2003. In September 2013, there were 7.4 million ‘mini-jobs’, which represented 17.4 per cent of the labour force between 15 and 64 years of age.

The proportion has been fairly steady since late 2007 after a rapid increase in the earlier years of the scheme.

The rapid increase in mini-jobs meant an increasing (and sizeable) proportion of the German workforce were forced to work in precarious jobs with extremely low pay and were excluded from enjoying the benefits of national income growth and the chance to accumulate pension entitlements.

Pay differentials have widened considerably in Germany since 2003 and various studies have found no evidence of large-scale worker transition from ‘mini-jobs’ to other, more regular work. ‘Mini-job’ workers are increasingly trapped in this form of marginalised employment.

The Government in cahoots with industry also engineered a massive redistribution of national income to profits and away from wages.

In general, German real wages (the purchasing power equivalent of the wages received by workers each week) failed to keep pace with growth in productivity (how much workers were producing each hour) and as a result there was a massive redistribution of national income to profits.

The following graph shows the – AMECO – (Annual Macroeconomic) database measure of Real Unit Labour Costs, provided by the European Commission (Annual Macroeconomic).

Please read the answer to Question 1 in the blog – Saturday Quiz – June 14, 2014 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on what RULCs mean.

Basically they are the ratio of real wages to labour productivity and if they are falling it means that productivity growth is rising faster than real wages and redistributing national income towards profits.

So the RULC measure is equivalent to the share of wages in national income. If it falls, workers have a lower share in real GDP.

The rise in the shares during the crisis signifies the fact that national GDP (output) was falling while total wages were not falling as fast or were relatively constant. As a consequence the ratio of the two rose.

Why does this matter? Until the early 2000s, real wages and labour productivity had typically moved together in Germany as they did in most advanced nations.

If real wages and labour productivity grow proportionately over time, the share of total national income that workers (wage earners) receive remains constant.

However, once the neo-liberal attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified in the 1980s in many nations and, later in Germany, a gap between the growth in real wages and productivity growth opened and widened.

This led to a major shift in national income shares away from workers towards profits.

The capitalist dilemma was that real wages typically had to grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold. If workers were producing more per hour over time, they had to be paid more per hour in real terms to ensure their purchasing power growth was sufficient to consume the extra production being pushed out into the markets.

How does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in the real wage, especially as governments were trying to reduce their deficits and thus their contribution to total spending in their economies? How does the economy recycle the rising profit share to overcome the declining capacity of workers to consume?

The neo-liberals found a new way to solve the dilemma. The ‘solution’ was so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever-increasing debt onto households and firms in many nations.

The credit expansion sustained the workers’ purchasing power, but also delivered an interest bonus to capital, while real wages growth continued to be suppressed.

Households in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed too good to be true and it was.

Germany adopted a particular version of this ‘solution’.

The funds to underwrite this credit explosion came from the increased profits that arose from the redistributed national income.

For some nations, such as Germany, the large export surpluses also provided the funds to loan out to other nations.

Germany didn’t experience the same credit explosion as other nations. The suppression of real wages growth in Germany and the growth in the (very) low-wage ‘mini-jobs’ meant that Germany severely stifled domestic spending up to 2005

The result was that growth (what there was) was driven by net exports and domestic demand was flat.

Schröder’s austerity policies forced harsh domestic restraint onto German workers, which meant that Germany could only grow through widening external surpluses.

So the external strategy, which has caused irreparable harm to its Eurozone partners, has also impoverished its own population. The German approach, which is echoed in the basic design of the common currency and the fiscal and monetary rules that reinforce it, could never be a viable model for prosperity throughout Europe.

Poverty rising in Germany

Which brings me to the most recent German poverty report mentioned in the Introduction – Der Paritätische Gesamtverband (HG): Die zerklüftete Republik.

The Report was published by – Der Paritätische Gesamtverband – which is an association of various social movements dedicated to advancing “social justice: equal opportunities, the right of every human being to live a life of dignity in which they can develop freely”.

It was formed “after the First World War as an alliance of hospitals” and now “encompasses more than 9000 organisations and working groups representing different aspects of the broad spectrum of social work”.

It is “Germany’s largest umbrella organisation of self-help initiatives in the area of health and social work”.

The Report’s main findings are:

1. The overall German poverty rate (measured as a person’s income being less than 60 percent of the average income after adjusting for household size) was 15.5 per cent in 2013 and rising. It is now at its highest level since the 1990 reunification.

2. 13 of the 16 German states experienced a rise in poverty rates.

3. The regions with the largest increases in poverty also had above-average economic growth.

4. The regional disparity is now much higher with the difference between the lowest and highest poverty rate area rising from 17.8 percentage points in 2006 to 24.8 percentage points in 2013.

5. The usual victims – the unemployed (60 per cent of them are poor) and single parients (40 per cent of them are poor) figure prominently. Both have endured rising poverty rates since 2006.

6. Child poverty is very high (“Die Kinderarmut bleibt in Deutschland weiterhin auf sehr hohem Niveau”).

7. The fast growing group in poverty are those on aged pensions.

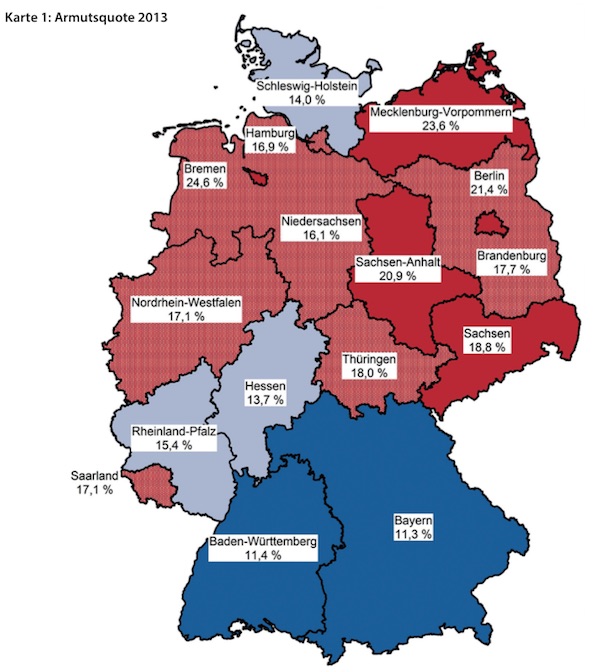

The following map (Map 1 in the Report) shows the fragmenting Germany regional society. This level of regional disparity is significant and poverty is clearly widespread.

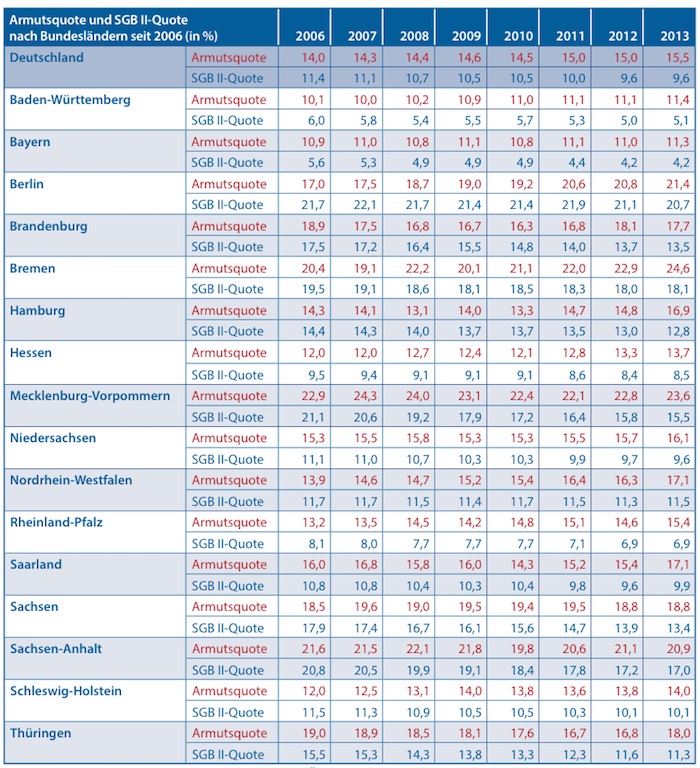

The accompanying Table (Tabelle 2 in the Report) compares the Poverty Rate (Armutsquote) with the SGB II-Quote from 2006 to 2013 across the States.

The SGB II ratio is the proportion of persons under 65 entitled to benefits (unemployment and social benefits).

It is clear that there is a negative relationship between those receiving unemployment and social benefits and poverty rates in the German States.

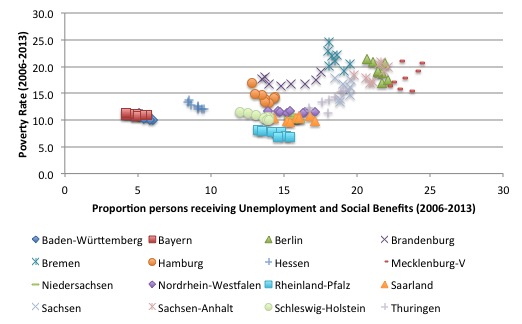

To give you a graphical view of that relationship and to highlight the degree of regional disparity (which is of course, magnified within states), I produced the following two graphs.

The first is graphing the relationship between the proportion of persons under 65 receiving benefits (SGB II ratio) (horizontal axis) for Germany from 2006-13 and the poverty rate.

The second graph plots the same relationship for the German States. The first graph shows the strength and consistency of the negative relationship at the Federal level.

The second shows the disparity between regions.

During the 2013 Federal election campaign, the German government used the slogan – “die Einkommensschere in Deutschland schließe sich wieder” (Continuing to close the income gap) – to divert criticisms of the damage that the Hartz IV labour market changes had caused to workers’ well being and poverty rates.

It is quite clear that the promise to reduce poverty is contrary to the evidence available in this Report.

The Report makes it clear that the relationship between economic growth and income poverty no longer exists (“Was den Zusammenhang von Wirtschaftswachstum (als Grundlage des volkswirtschaftlichen Reichtums) und Einkommensarmut anbelangt, lässt sich keine sinnvolle Korrelation mehr erkennen”)

So that economic growth no longer reduces poverty. Why is that?

The reason for the decoupling of economic development and poverty trends is not that economic growth doesn’t produce wealth (sorry for the double negative).

It is that the growing inequality has concentrated the rising wealth and the rising poverty rates are evidence of that.

Even the relationship between poverty and unemployment has changed. The Report notes that since 2006 the poverty rate has risen while unemployment rates have fallen.

The clue to these various linked trends is the growth in the “working poor”. The Report says that:

Wenn Armutsquoten steigen, während die Arbeitslosenquote ganz deutlich sinkt, und die Zahl der Langzeitarbeitslosen, die sich hinter der SGB II-Quote verbirgt, mehr oder weniger stagniert, so weist dies zum einen auf das Phänomen der „working poor” hin, das in Deutschland, beschleunigt durch die Hartz-Reformen

In other words, they are linking the rising poverty rates and declining unemployment to the rise of the working poor created by the Hartz ‘reforms’, which created a growing number of people in the low-wage sector and the rise of precarious employment.

Well-paid employment is falling in Germany and the benefits from growth are being increasingly enjoyed by fewer people.

The rump of low-paid workers who live below the poverty rate is now rising as a consequence.

That is not a model for Europe.

Conclusion

Here is a – Photo – taken by Jan-Philipp Strobel for Agence France-Presse, of a homeless man lying in a street in Dortmund on October 25, 2013.

The blanket he is using for some warmth bears a striking similarity to a national flag south of Germany! Irony.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

From the historical perspective it appears that Germany has been little more than a problem for Europe ever since the rise of Prussian domination under Bismarck and the first Kaiser in the latter half of the 19th century.

Maybe it is Germany which should leave the EU rather than Greece,Italy,Spain,Portugal and Ireland.

I’m sure that Vlad the Putrid would welcome his Western partners in crime into the Russian fold.

I am far from applauding the economic policies of German government but one thing was only mentioned marginally – poverty rate is greater than 17.5 % in all provinces of former East Germany and lower in all the provinces of the former West Germany except for Bremen. This suggests that even over 25 years after the fall of the German Wall the dark socio-economic heritage of communism and “real socialism” is still there.

It would also be interesting to see the ethnic background of poor people. “Almost a third of all men and women with foreign roots between the ages of 25 and 35 have no professional qualifications. The data is especially alarming for the roughly three million Turkish immigrants, Germany’s largest minority. The share of young Turks with no professional qualifications rose from 44 to 57 percent between 2001 and 2006. This figure alone — 57 percent — perfectly illustrates the sheer magnitude of the failure on both sides.” At Home in a Foreign Country: German Turks Struggle to Find Their Identity Der Spiegel November 02, 2011

I can quote statistics about unemployment among descendants of non-assimilated migrants etc but it is obvious that we cannot reduce German social and economic problems to just one dimension – flawed macroeconomic policy bent on reducing the income of the so-called working class. Let’s compare Turks and Poles. It is interesting to see that children of people who moved from Poland (often already with German roots) usually don’t even speak Polish (see the note in Wikipedia) – they are assimilated almost immediately, even if they complain about initial difficulties. A lot of people in Western Poland have German heritage and effectively belong to Germanic culture – even Mrs Merkel’s grandfather was called Kaźmierczak.

I dare to say that it is the culture what plays enormous role in determining the fate of the descendants of the migrants. A Kashubian will only need to polish his German – his culture is already a mix of Germanic and Slavonic heritage. A Turk is a Muslim, his culture is alien to Western Europe and he will never be accepted by a lot of conservative Germans as one of them even if they maintain a basic level of politeness.

I wonder whether there is more happening than just poor macroeconomic policy? Yes, I do agree the EU and the euro are badly flawed in design and this is causing enormous problems for Greece, Spain and some others. Eventually, it will mire the whole EU in a permanent recession or even depression. Clearly, Greece and Spain are already in a depression.

However, I think two other things are happening. One, the entire developed world is suffering low growth or stagnation as capitalism moves manufacturing to the low-wage developing nations. Two, the world is approaching or is even at the limits to sustainable growth and sustainable production. The EU malaise may go far deeper than just bad macroeconomics. Indeed, it may presage what is soon likely to happen to the rest of us.

There is mainly one reason and it is the biggest reason for Germany’s rise in it’s economic status and that reason is “fractional reserve banking”. You may call it capitalism, which it’s not definately not, but I call it psychopathic economics.

Reading recent interviews o fEric Toussant, it seems Germany has benefited greatly from past favors (see http://cadtm.org/In-February-1953-the-allied-powers ). Now that it gained from those past leniancies and favors German politicians and elites want to change the rules for the rest of Europe. I’m not saying the German people didn’t or don’t work hard, cause the do work hard, but it’s not the case that Germany got to where it is today because of hard work by the German people.

4. A declining percentage of workers without formal educational qualifications now make up the low-pay workforce. In other words, formal education is now longer a guarantee (as it was in the past) of a well-paid job in Germany.

Bill, the second sentence doesn’t seem to be a restatement of the first and, therefore, does not seem to follow from it.

Excellent post.

I do not think that German political elites really thought they had to “devaluate” regard to other European nations. They rather thought the price of labour had to go down so that more labour was demanded. It was the simple, idiotic “labour market” logic. If the price for a commodity goes down, demand goes up … . Only that without the ECU thinks hadn’t wrought out, because DM would have gone up …

Dear Bill

25% of Germans earn less than 10 euro per hour. In France, this percentage is much lower. The slogan of the Schröder government was Fördern durch Fordern = encourage people by making demands on them. The idea was to get people off social assistance and into the labor force. From a neoliberal point of view, they may well have been successful. To neoliberals, a person with a low-paying job, no matter how low the pay, is always to be preferred to a person on social assistance.

You didn’t mention the employment rate. The German employment rate may well be very high because the share of the population between 18 and 64 has been falling in Germany as the number of people who retire is larger those who enter the labor force. In such a situation, it isn’t necessary to augment the capital stock in order to accommodate a growing labor force. Also, the employment rate may have been increased by forcing people on social assistance into mini-jobs.

German economic policy gets a lot of criticism from the left and from those who recognize that running large current-account surplus is not the best way to create jobs, but the Netherlands resembles Germany in many ways. The Dutch current-account surplus for 2014 was a whopping 11% of GDP, while in Germany it was 7%. Switzerland and Sweden have also been running large current-account surpluses. That of course means that in those 4 countries, people are living below their means. Each Dutchman could consume almost 4000 euros more if the Netherlands didn’t have such a ridiculously large current-account surplus.

Regards. James

Very creepy economic documentary on the euro thingy. followed by a debate on BBC 4 last night.

The debate was essentially between two Rothschild ciphers.

The producer of the programme (of the economist magazine) who was pro further euro integration and a sceptical Norman Lamont.

.

You could see quite clearly the power behind these “nations” engaging in a cost benefit analysis.

Social creditors would obviously reject the labour theory of value stuff that Bill projects.

The problem is the concentration of capital ownership.

The above guys have seized all of the commons including most importantly the money.

Certainly in the British isles since Tudor times and in all of Europe since the creation of the modern sov bond market in the 19 the century.

If each German was given a slice of the pie ( to become mini capitalists if you will) there would be no need for overproduction in the first place.

Germany is sovereign only so far as it is given the latitude to offload the costs of overproduction via extreme force feeding of mercantalism.

For example Ireland is experiencing a growth of internal consumption that is almost entirely concentrated in the car market,

The dynamics of this is quite in increditable.

The success of euro drones is judged entirely on their ability to absorb dumped goods..

Larry,

“Bill, the second sentence doesn’t seem to be a restatement of the first and, therefore, does not seem to follow from it.”

It does, you just have to read it more carefully: replace this statement with one that means the same thing:

Kind Regards

As it seems the German “internal devaluation” primarily targeted the domestic market, squeezing import. Not sure but I belive pay in the big export industry sector is good. Both engineers and workers have good salary structure. In 2004 GM had an fake competition for a new car between it’s Swedish Saab factory and it’ splint at Russelheim Germany. Despite brut workers cost in Germany was 30-50% higher Russelheim “prevailed”. Germany was probably pre-decide, an attempt to squeeze wages in Germany.

Seems like anyone don’t working in the mighty export industry isn’t wort living in Germany, there is also reports that German infrastructure is seberly neglected due to theire irrational budget restrictions. E.g. the Kiel canal is decaying.

Last week, I ran across several reference (sorry don’t recall where) to the German military as being almost non-functional due to budget cuts required to keep their government within Eurozone requirements. One of the references even noted that the military was using broomsticks as guns during drills, there not being a sufficient number of real guns available to them, and also noted that morale was (of course) extremely low as a result. If this is true, it’s clear evidence that the Euro simply does not function as a viable currency no matter how a country tries to accommodate its restrictions.

(It also might explain why Merkel was so quick to meet with Putin about diffusing the Ukraine situation. Germany would hardly be in any way ready to perform her promised NATO role should that situation escalate. (But certainly, the US would know this?))

” that even over 25 years after the fall of the German Wall the dark socio-economic heritage of communism and “real socialism” is still there …”

Really ? So what do you know about this gruesome ‘heritage’ ? That these people are lazy losers because they haven’t learned how to work ? For 25 years, now. Tz, tz.

Isn’t it kind of weird that the glorious market economy doesn’t seem to be able to create prosperous areas throughout the eastern part of the great Germany ? Not ? Not even in 25 years ? How come ?

Especially when you think about the fact, that 95% of the owners are not of East German origin.

And that the vast majority of the political administration officials came from West Germany, in the 90’s.

Oh – and that the wages in the Eastern part of Germany are generally lower, til today.

How come the magic isn’t working as promised ?

Oh, well, I forgot: the “dark socio-economic heritage …”

I envy your well-fortified bonehead-vision of the way the world works.

Bill,

I just came across this comment of yours, written in 2012:

So Europe abandons any notion of democracy. The German ideology that could not prevail in several World Wars would thus prevail. Greece leaves the Eurozone and becomes a colony of the Eurozone.

This may have seemed unduly harsh at the time. Much less so now. I’d just add that the whole of the Eurozone is becoming (has become?) a Dutch/German colony.

/L,

“pay in the big [German] export industry sector is good” .

That may well be true. But, fundamentally, Germans need to ask themselves the question of why its ALWAYS better to exchange more goods and services for fewer goods and services. It may make sense to do that for one year, or maybe a few years but year after year? What’s the point?

If I grow apples and you grow pears then it makes sense for us to swap, say, 5 kg of my apples for 5 kg of your equally valuable pears. If, one year, I can only supply 4kg of apples then you can take my IOU to make up the difference. That’s fine if the situation reverses the next year.

But if this goes on for too long, year after year, you’ll end up with lots and lots of my IOUs. You’ll get worried about my ability to repay and rightly so. Just like Germany is worried about Greece’s ability to repay. So, why let it happen to begin with? Germans should do themselves a favour and at least balance their trade. That way they can eat more apples and pears! Better still they could try running a deficit. They have plenty of foreign currency reserves, and credit worthiness, to do that and they will be giving Greece and Spain a market for their exports. This will boost their economies and allow them to better service their Euro debts.

It is even worse. When you run a critical blog about a Jobcenter they demand a take-down of a blog post, or face a €10,000 (ten thousand) fine. They did not even like a Dilbert quote!

The local court refuses to prosecute the Jobcenter man. director for criminal blackmailing.

They report you to authorities for certain publishings which are covered by Germany’s basic law and they get your computer confiscated. Mine is gone since 24 months.

They try to get your kid out of school and into a low paying job.

When you are a critical blogger they do everything to destroy your business when you are self employed.

They recommend you companies for loans that charge up to 14% interest.

They deliver letters to you deliberately late so that you are in breach of contract. There’s lots more.

Jobcenters are legal criminal government agencies.

Not everything is rosy and shiny in Germany, agreed.

But you are using two very problematic charts here:

Having a Minijob doesn’t automatically equal to being a “working poor”. The vast majority of Minijobs are used for part-time work, because there are a lot less bureaucratic hurdles to overcome than for a regular job. Mind you, even my mum has a Minijob, because she still enjoys to work at a kindergarten at the age of 77. She uses the extra money (next to her pension) to travel around the world (quite literally for that matter). Only 218,000 people work fulltime in a Minijob and are subsidized by the government (http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/hartz-iv-aufstocker-gut-ein-drittel-weniger-in-vollzeit-gezaehlt-a-950342.html I couldn’t find an English version, sorry).

Besides, after almost 70 years of peace a lot of wealth has accumulated in Germany and is passed down to heirs who in turn can afford to make a living of a Minijob. I personally know some of these lucky bastards. So working part-time doesn’t infer that you couldn’t get a full-time job.

There were always a lot of subsidized jobs in Germany, but they weren’t in the open. Every state-run or state-controlled company had the lot of them. Remember that a one-minute long-distance telephone call used to cost around 0.60€ in the 80ies and you know were the postmens’ wages came from (postal and telecommunication services being run by the same government branch at the time).

Secondly, the way the poverty quote is calculated makes sure that there still will be poverty in Germany even if everyone (and their grandmother) were a billionaire. How’s that, you might ask. Simple: everyone who earns less than 60% of the median income is considered to be poor. Now, unless everyone has exactly the same income, there will always be poor people in Germany. The “Paritätischer Wohlfahrtsbund” isn’t an observer here, but an actor, so it is inevitably biased. The more they cry, the more money they get. And that revenue doesn’t come from their customers, but from public sources, read from the taxpayer.

Lastly, unlike other countries, wages are negotiated mostly without state influence. Both sides, unions and employers, really don’t like it when government interferes and violently say so. And though the number is in decline, still most people’s wages are set by collective bargaining agreements.

So blaming the government (especially the federal one) for not raising the wages enough is besides the point.

Here somebody is telling some tall stories. You cannot compare the US system with Europe. A refugee costs 15.000 Euros and more in a single year in Germany. This is not poverty! You cannot compare poverty in USA with poverty in Germany. Nobody is starving or suffering hunger there. The poverty problem is mainly the problem of the underclass of immigrants. They have no real function. The result of the “open society” of a Europe after US model. The term “Germans” for these people is completely wrong. Hartz IV – “workers” are not the reason for the German export! They are no professional workers. You are comparing apples with pears!

Dear All

My comments policy makes it clear that I expect a credible E-mail address with any comment I publish. I don’t use it for anything other than to verify a human is involved. Irrespective of the validity of the comment, it will go to trash if there is a blatantly false E-mail address accompanying the comment. For example, an address such as no.no @ no.no will be immediately deleted.

best wishes

bill

That’s actually a misconception. Having the threshold at a certain percentage of the median income means the raising the incomes of those below the threshold does not in and of itself increase the threshold.

http://www.poverty.ac.uk/definitions-poverty/income-threshold-approach