The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Germany should look at itself in the mirror

It has been argued for some years that one of the important consequences of Germany’s obsession with fiscal surpluses in recent years, articulated by Chancellor Merkel and Finance Minister Schäuble as the “Schwarze Null” austerity policy, is that Germany has been under-investing in its physical infrastructure. But it has taken the recent industrial unrest to bring that to the fore into the public debate. Even the IMF is now getting on the bandwagon. In its in-house journal (Finance and Development, Vol.52, No.2, June 2015) there was an article – Capital Idea – which says that “By increasing spending on infrastructure, Germany will help not only itself, but the entire euro area”. At present, Germany is trying to take the high moral ground in the Greece negotiations, but its motivations are obvious – it doesn’t want the generosity that the rest of the world has shown to it in the past (debt forgiveness) to be given to Greece now because that would allow the Greek government to stimulate growth and demonstrate that the austerity path is destructive and myopic. It doesn’t suit Germany’s own vision of itself (as articulated by its own crazy government) for an anti-austerity stance to be given any oxygen. But if it looks at itself in the mirror it would see an economy that is barely capable of economic growth itself, most recently has zero employment growth, has decaying physical infrastructure such that bridges are roads are becoming dangerous, has generated no meaningful real wages growth in years, and as a consequence, has a workforce that is now showing signs of open revolt. Some moral high ground.

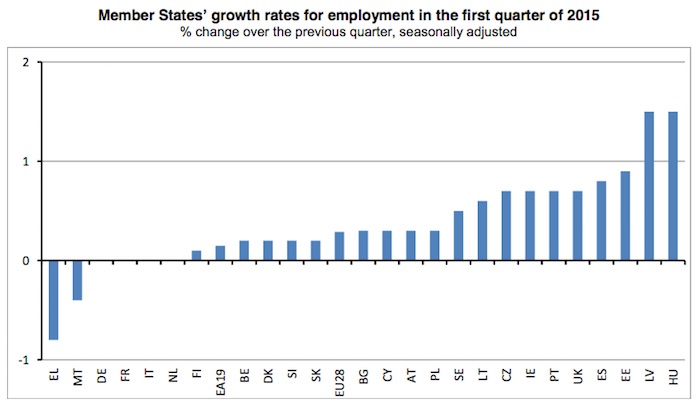

Eurostat published the latest employment data yesterday (June 16, 2015) – Employment up by 0.1% in euro area and by 0.3% in the EU28.

The result is abysmal and a reflection of the failed policy structures in place in Europe at present.

Total employment in the Eurozone is still around 3 per cent below the peak before the crisis – that is, it has still not recovered the level it attained – 7 years ago.

In the last four-quarters, Germany has recorded employment growth rates of 0.3 per cent (2014Q2), 0.1 per cent (2014Q3), 0.2 per cent (2014Q4), and now 0.0 per cent (2015Q1).

As you can see from the graph, Germany (DE) is now the third worst performing economy in the European Union. And if you believed all the hype last year about Greece finally turning the corner as a result of the austerity policies check out its employment growth in the first-quarter of 2015 – minus 0.8 per cent.

The austerity straitjacket has led the three largest economies in the Eurozone (Germany, France and Italy) to record zero employment growth in the first-quarter 2015.

It is little wonder that industrial action (strikes etc) have rather dramatically increased in Germany in recent years.

Earlier in May 2015, the German press carried the headline – Willkommen, Streikrepublik Deutschland – which I am sure doesn’t need translating.

It was reporting a six-day strike at the German railways (Deutsche Bahn) as the – Gewerkschaft Deutscher Lokomotivführer (GDL) – the German train drivers’ union (the or GDL) increased the intensity of its wages and conditions campaign that started in the Autumn of 2014. The strike in May was the 8th that the GDL has organised over that period.

Industrial unrest is, however, not confined to the railways in Germany. The UK Guardian article (May 22, 2015) – The strikes sweeping Germany are here to stay – noted that Germany:

… is on course to set a new record for industrial action with everyone from train drivers, kindergarten and nursery teachers and post office workers staging walkouts recently. The strike wave is more than a conjunctural blip: it is another facet of the inexorable disintegration of what used to be the ‘German model’.

Germany’s international broadcaster Deutsche Welle noted in the report (May 14, 2015) – Germany to mark record year for strikes – that “German workers have already been on strike for twice as many days this year as they were in the whole of 2014”.

The damaging Hartz reforms which have increased precarious employment and stifled real wages growth combined with privatisations and attacks on unions have led in the opinion of the UK Guardian author to a “a broad erosion of formal and informal wage norms that for several decades kept the peace in German capitalism”.

Income differentials have been further strained by the “enormous, Anglo-American-style increases in top management salaries, especially, but by no means exclusively, in finance”.

The UK Guardian article notes that:

Skyrocketing managerial pay is out of joint with the experience of the vast majority of households, who suffer not only from stagnant or declining wages and deteriorating employment conditions, but also from cuts in public services and benefits. This makes appeals to workers for wage restraint for the benefit of the public and the economy sound hypocritical to many.

Overlaying and driving all of this malaise is the fiscal austerity (the ‘Schwarze Null’ policy) of the Government. So as it lectures Greece on how it should act, its own handling of the German economy is leading to a breakdown in the stability of its own society.

Who the cap fits!

The Jacobin Magazine article (June 15, 2015) – The Upsurge in Germany – notes that:

The government’s goal of avoiding debt at all costs has been achieved at a huge expense. German cities and municipalities have been bled dry, schools are falling apart, and bridges are near collapse.

There are two implications of this.

The industrial unrest is directly challenging the austerity model because the local governments are under pressure to increase wages and improve services at a time when the federal government is squeezing the public sector generally.

The decline in infrastucture is also demonstrating the poverty of the austerity model.

This decline has been on the radar for a while now. Last year (September 18, 2014), the German magazine Der Spiegel published an article – Germany’s Ailing Infrastructure: A Nation Slowly Crumbles – which said that “Despite its shiny façade, the German economy is crumbling at its core.”

The article cites the new Director of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) who has recently published a book – “Die Deutschland Illusion” – the title is self-explanatory.

We learn that:

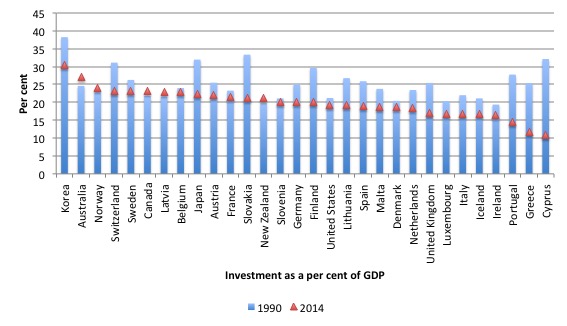

Hardly any other industrialized nation is so negligent and tight-fisted about its future. While the government and the economy were investing 25 percent of total economic output in new roads, telephone lines, university buildings and factories in the early 1990s, the number declined to only 19.7 percent in 2013 … the investment shortfall between 1999 and 2012 amounted to about 3 percent of gross domestic product, the largest “investment gap” of any European country. If one looks only at the years from 2010 to 2012, the gap, at 3.7 percent, is even bigger. Just to maintain the status quo and achieve reasonable growth, the government and business world would have to spend €103 billion ($133 billion) more each year than they do today.

That ratio did not improve in 2014.

The following graph (using AMECO data) shows the Gross Investment as a percent of GDP for 31 nations as at 1990 (blue columns) and 2014 (red triangles). It is ranked in terms of the 2014 ratios.

There are not too many Eurozone nations in the above-average group (over 21 per cent).

It is clear that German companies are cashed up and “no longer investing in Germany”. The article lists alternative locations where the German capital is heading (US, China, etc).

So while the autobahns crumble and the electricity transmission system approaches collapse, Germany is also underinvesting in its human skill development.

The article notes that Germany is lagging behind other OECD nations in its spending on “daycare centers, schoools and unversities … The level of early-childhood education in Germany is ‘in the poor-to-moderate range'”

The upshot is that Germany needs to:

… renovate its factories, transportation arteries and data networks, educate its young people more effectively and devise new ways to use the vast savings capital of its citizens in economically meaningful ways.

But it cannot do that if it maintains the balanced (or surplus) fiscal strategy.

And now the IMF is finally waking up to this disaster.

In its article (cited above), we learn that “even the strongest economy” in the Eurozone, “Germany, seems to have lost some momentum in recent years. Moreover, estimates of German growth potential are low-and could go lower because of a rapidly aging population.”

The IMF article argues that:

But there is a way to mitigate growth problems in Germany and, by extension, throughout the euro area. Increased German public investment in infrastructure, such as highways and bridges, would not only stimulate near-term domestic demand, but would also increase productivity and raise domestic output over the longer run and generate beneficial spillovers across the rest of the euro area.

Which is a refreshing change from the “growth-friendly austerity” that the IMF has been pumping out during the crisis to justify their role in the Troika, which has all but killed off Greek prosperity.

Here we have a recognition that spending equals income and that government spending not only directly stimulates domestic demand but also leads to multipliers which will benefit the other nations in the Eurozone.

The IMF also now recognises that “Germany’s public investment in infrastructure is in the bottom quarter of the 34 advanced and emerging market economies of the” OECD.

The reality is that “public investment has been negligible since 2003” and it is only so long that bridges and roads can tolerate virtually zero maintenance.

An increase in public infrastructure spending not only stimulates demand now but also increases potential real GDP (future growth) and future productivity growth, which provides an increased capacity for employment growth and real wages growth.

It all feeds on itself in a virtuous cycle.

The same strategy should be advocated for Greece. It cannot meet the fiscal targets imposed by the Troika without growth and the conditions imposed as part of the bailout prevent growth. They are caught up in a vicious cycle.

The solution is the same as it is for Germany – more public spending.

It isn’t rocket science.

Conclusion

If Germany could look at itself in a mirror it would see an ugly nation – failing in many respects to provide for the well-being of its people.

In turn, its social model is starting to break down.

Things have to change.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill good article as always. Unfortunately as the issues post GFC are now still going without major I imagine it’s going to be sometime before this plays out too sadly. The more I read about police brutality in the USA (mini revolutions of poor people mainly black) and severe lack of infrastructure investment there I sense that there is likely to be a revolution at some point with most people uprising once inequality gets to a tipping point. Your guess is as good as mine on how long that will take. The only hope I see to stop this is if Bernie Sanders is able to cut through all the big money in politics there and win the presidency hopefully. At he worst he may be able to push Hillary to move much further to the left and stay there. I think we will hopefully see a JG in our lifetime if things play out how I imagine. Unfortunately it’s going to take something big to make it happen as the super rich seem to be content amassing huge amounts of cash in banks. That money isn’t going to be much use to them when the masses uprise against them unless they hire there own mercenaries to try and delay it. We need some politicians who see the bigger picture and can understand and utilise MMT for the good of humanity!

The good news is that when DeutscheBank finally goes Lehman, with all the ripple effects across Europe and the world, we will have a chance to do 2008 over again, this time using the space left by collapsing private investment to pump money into green infrastructure — we are probably looking at low inflation for years to come, so a massive reversal of our errors since the GFC is possible!

I would like somebody to point me in the direction of neolib statements about how government/business austerity can lead to growth. I hear government halfwits and business gurus talking about reigning in spending but is there really an economic thesis which puts forward the idea that nobody spending is a recipe for growth?

Excellent analysis. German politicians are notorious for their unwillingness to accept or publicise the reality that they have extensively used heterodox policies to develop their country. Their current self-flagellation over public spending is a continuation of this intentional ignorance. As people like Linda Weiss have shown (“The Myth of the powerless state” 1998), during the era of West Germany, its neoliberal politicians were totally unwilling to publicise the success of its huge amount of national and regional state intervention, creative forms of public ownership, and its powerful ‘developmental state’ apparatus, which were the key drivers behind its post-war recovery and which by the 1970s had turned the country into Europe’s industrial and technological powerhouse. Instead, for fear of publicising the obvious benefits of such state-driven development instruments at a time when the capitalist west was in ideological competition with the former Soviet Union, they went along with the false notion put about by neoliberals that West Germany’s success was all down to the free market and private ownership. Sad that today Merkel is willing to progressively dismantle and destroy a very successful development model in order to give space for the ideologically pure development model she and others around her prefer and fixate over, but a development model that has no track record anywhere of long-term success.

The function of a economy should not be growth for growths / jobs sake.

It should provide adequate goods for human (and not corporate needs).

Further investment is more concrete , anti family schools / industrial factory farms, Kinder gardens for effectively motherless children etc etc is not what Bill says on his MMT tin.

This in reality is the nightmare corporate world of today.

A world populated by automans.

Wage roboten.

Investment ( under current monetary conditions) = more costs.

Kel

I’m no economist but maybe look at Ricardian Equivalence and The Crowding Out effect.

Looks like bollocks to me but for all I know they may still use these to fuel their arguments.

When I was living in Germany in 2000, most of the complaints I heard were about the East Germans and how they were getting benefits denied to the average West German, focusing primarily on the increase in health care contributions. While that was true, reasons were given for that by the government. But the complaints didn’t begin until around 10 years after unification when the average West German thought 10 years was long enough to adjust to the West German way of doing things. The children were adjusting but their parents were not. At the same time, German construction workers sometimes were able to take two hour lunch breaks, especially those working on the highways. The reason given to me was that construction was hard work and, to do it well, people had to eat well and they might have to travel to a good eatery. This travel time should not count as part of their lunch break. I thought, how civilized.

I am a little baffled by Merkel’s attitude. Having gown up in East Germany, one might have thought that she’d be less strident, especially about austerity.

For those interested, here are the links to the IMF’s explication of their GIMF, Global Integrated Monetary & Fiscal Model.

The most recent, by Anderson et al., Feb 2013, Getting to Know GIMF: The Simulation Properties of the Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal Model:

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1355.pdf

An earlier one, Feb 2010, concentrating on the theoretical structure of the “model”, by Kumhof et al., The Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal Model (GIMF) – Theoretical Structure:

https://web.stanford.edu/~kumhof/gimfwp1034.pdf

This is the basis of their analysis in Capital Idea. It seems as though the policy arm of the IMF does not communicate with their own research arm and even ignores it. For instance, the research department has said that austerity might be relaxed while simultaneously Lagarde was promulgating further austerity. She gets away with this and hardly anyone seems to comment on this disconnect.

I should have mentioned that the IMF’s GIMF “model” is a DSGE structure focusing on households and firms that they believe has macroeconomic policy implications. The IMF researchers, in their simulation paper of 2013, contend that their DSGE equations are non-standard because they impose “finite horizons” on their equations and, moreover, claim them to possess two non-Ricardian features — households are liquidity constrained & have finite horizons (Blanchard). And they make most of these points up front. They contend that counter-cyclical fiscal policy, focusing a lot on taxation, will allow long run stability. And they advocate government spending to increase aggregate demand, distinguishing between government investment and government consumption — investment is the better strategy, as its effects last longer. In other words, improving infrastructure is better than, say, buying tanks. Well, yeah.

However, in the IMF paper, Fiscal Stimulus to the Rescue?, by Freedman et al. (2009) (note the ?), the contention appears to be that high government debt has long-run negative effects. All the papers are long and complex and are intended to reinforce one another. I won’t take up more of Bill’s space by saying more, as I think I have given an idea of where these researchers are coming from and going. And Bill has already said what he thinks of DSGE techniques in general, though as I mentioned IMF researchers believe their approach in these papers to be non-standard.

The germans have been the worlds scapegoat again and again.

The unwillingness to cut the greeks debt is a bankster descision as like

the joining of greece into the euro was (just google goldman sachs role in it).

The german politicians follow the a policy against their own public as the same

way the city of london and the FED does to britain and the usa.

You better start asking yourself about the medias intentions… the propaganda

going on recently (e.g. against russia) is leading to war yet again.

[Bill edited out an unsavoury video that has no relevance to the economics discussion]

The debt of the ones is the capital of the others… look at the debts of all western

countries and hold over a sheet with the dates of the biggest wars.

All germans i know ( i am german ), want to help the greek people by cutting the debt

eventhough it means the bank-debts from 2008/2009 are now the publics debts… thanks to our pilticians.

The finance system is showing its real face. Look at the poverty in the states ! Third world

conditions all over ! People should stop blaming countries and their citizens ! German people are peaceful and all americans i know (stepfather is american) are as well. So are the poor greek people that starve as we speak, while ukranians die as we speak… in EUROPE !

THIS HAS TO END

As I have said before, the way to stop this madness is to get the Germans to exit the euro – reducing inflation and boosting their savings – then forcing the hand of the government to run expansionary policy.

Euroarea GDP per capita peaked 8 years ago and has been in declining trend line ever since: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/euro-area/gdp-per-capita

Notice also breaking trend line of the growth at the beginning of the euro, so that peak in the 2007 was already below growth that could have been attained without euro.

Statistics say that euro is not good for europe. It’s pure and simple. People need to point this out, because eurofandom still runs strong, and it is based on nothing.