The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

German external investment model a failure

I read an interesting research report recently – Exportweltmeister: The Low Returns on Germany’s Capital Exports – published by the London-based Centre of Economic Policy Research (CEPR) in July 2019. It tells us a lot about the dysfunctional nature of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and Germany’s role within it, in particular. Germany has been running persistent and very large external surpluses for some years now in violation of EU rules. It also suppresses domestic demand by its punitive labour market policies and persistent fiscal surpluses. At the same time as these strategies have resulted in the massive degradation of essential infrastructure (roads, buildings, bridges etc), Germany has been exporting its massive savings in the form of international investments (FDI, equity, etc). The evidence is now in that the returns on those investments have been poor, which amounts to a comprehensive rejection of many of the shibboleths that German politicians and their industrialists hold and use as frames to bully other nations

The CEPR article starts by introducing us to the term “Stupid German Money”, which comes from the way the German government helped fund the US movie industry when it was really aiming to stimulate its own movie production sector.

On February 5, 2004, the German media academic Matthias Kurp published an article – Mediafonds als “Stupid German Money” – which told us that in the previous five years, German investors had pumped €10 billion into so-called media funds as equity participation.

The inducement was the tax write-offs that were held out by the German government on these investments.

The reality was that around 80 per cent of the investment funds went to the US (Hollywood) and very small amounts went into the German film industry despite the tax advantages being provided to bost the German film industry.

The tax advantages mean that the investor writes off the ‘loss’ immediately and, then, if the film is profitable can enjoy the profits, often, according to Kurp, long into the future often as a retired (low-tax bracket) person.

The “Hollywood bosses” termed these investments “stupid German money” because the US film industry gets funded, the German investors get tax advantages and the German Ministry of Finance picks up the tab.

The CEPR paper notes that in the Hollywood movie “The Big Short”, the concept of ‘stupid German money’ is generalised and we see:

… a senior executive at Deutsche Bank, Greg Lippmann, tours Wall Street in 2007 to short-sell securities containing US subprime mortgages. When asked who was still buying these toxic, high-risk papers, “he always just said: Du ̈sseldorf”

The concept of “stupid German money” motivates the research presented in the paper. The authors ask the question “Are German investment returns particularly low, and if so, why?”

As background, we need to take a step back to understand the CEPR conclusions (which I present later).

Germany determined well before other Eurozone nations that they would adapt to the fixed exchange rate they faced once they entered the Eurozone by suppressing domestic demand – public and private consumption and capital formation investment – through its attacks on wages growth and fiscal austerity.

Previously, the Bundesbank was able to manipulate the exchange rate to ensure its manufacturing sector remained internationally competitive.

Once it entered the Eurozone it had to manipulate domestic costs – so they were the first to engage in deliberate ‘internal devaluation’ (Hartz, etc).

Coupled with an increasingly austere fiscal outlook, Germany was able to stifle imports, run persistent current account surpluses well above the allowable European Union thresholds, and build up massive financial claims against the rest of the world.

I wrote about these matters in detail in these blog posts (among others):

1. Germany – a most dangerous and ridiculous nation (December 27, 2017).

2. Massive Eurozone infrastructure deficit requires urgent redress ( November 27, 2017).

3. Wolfgang Schäuble is gone but his disastrous legacy will continue (October 16, 2017).

4. The chickens are coming home to roost for Europe’s so-called powerhouse (August 10, 2017).

5. More Germans are at risk of severe poverty than ever before (July 6, 2017).

6. German trade surpluses demonstrate the failure of the Eurozone (April 24, 2017).

7. Germany should look at itself in the mirror (June 17, 2015).

8. Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home (March 2, 2015).

9. The stupidity of the German ideology will come back to haunt them (September 2, 2013).

10. The German model is not workable for the Eurozone (February 3, 2012).

As you can see – it is a long list (of an even longer list) – going back well into the crisis.

The facts are that I started writing about these matters in social media in early 2005 (Source), well before crisis began and published academic papers earlier than the crisis on the way the Germans were manipulating the Eurozone to its advantage and imposing costs on its Member State partners.

And since that time, nothing much has changed despite the GFC exposing the folly of the German position.

The inference that the German approach has been static, is, in fact, not quite right.

As Wolfgang Münchau wrote in his recent Financial Times article (August 5, 2019) – Germany is replaying Britain’s Brexit debate – the reality is that:

It is impossible to predict how Germany will confront the dual threat of a fundamental technology shift and a monetary union plagued by imbalances. The best solution would be to fix the problem by doing whatever it takes to make the monetary union sustainable; ending the obsession with fiscal surpluses; and increasing investment in science, technology, and military infrastructure. But that would be a triumph of hope over experience. Germany is moving in exactly the opposite direction.

So Germany is shifting – but only by intensifying the ridiculous position that is destroying the chance that the EMU can deliver prosperity.

And those shifts are now coming back in the form of the renewed likelihood of recession, which I analysed in this blog post last week – Germany is now suffering from the illogical nature of its own behaviour (August 13, 2019).

What happens when Germany runs such large external surpluses? The net outflow of real goods and services is accompanied by accumulating financial claims against the rest of the world.

The high level of German savings may have gone into the domestic economy if there were profitable opportunities to invest. But in Germany’s case, its whole strategy was based on suppressing domestic demand (Hartz reforms, wage suppression, mini-jobs etc), and so profitable investment opportunities were limited in the German economy.

As a result and capital sought profits elsewhere.

The persistently large external surpluses which began long before the crisis (and 6 per cent is large) were the reason that so much debt was incurred in Spain and elsewhere. German investors pushed capital externally.

Germany is clearly supplying large flows of capital to the rest of the world.

German citizens generally have been led to believe that these external surpluses are ‘good’ – the outcome of the relentless pursuit of external competitiveness and the superiority of German industrial know-how and efficiency.

Regular contributions in the literature have downplayed the suppression of domestic spending as the source of the exported savings.

For example, there was an article in The International Economy magazine (Fall 2014) – The Empire Strikes Back – by the Director General of the German Ministry of Finance, Ludger Schuknecht – which carried the sub-title “Why Germany’s exports and current account surpluses benefit other countries”.

Schuknecht sought to counter criticism of the huge German current account surpluses and dispel the notion that they were thre result of depressed domestic spending (in part).

He wrote:

Germany’s exports not only benefit Germans, they very significantly benefit other countries as well … the German current account surplus reflects a lot of foreign direct investment. Is this bad?

And the surpluses reflected (in part):

I mentioned the policy reforms that strengthened Germany’s competitiveness over the past ten to fifteen years. at the same time, some of our trading partners allowed import booms related to construction, expansionary fiscal policies, and excessive wage growth.

Mainstream economists have long argued that a nation can shift the risk of demographic change (ageing) by pumping capital into economies with younger demographic profiles.

For example, Alan Taylor and Jeffrey Williamson published an NBER Working Paper in 1991 – Capital Flows to the New World as an Intergenerational Transfer (subsequently published in 1994 by the Journal of Political Economy, 102(2), pp.348-371) – which argued that in the “New World” immigration and high fertility rates choked off “domestic savings” and created “an external demand for savings”, which capital flows from the “Old World” (Britain before WWI) that provided intergenerational transfers.

These external flows also allow a nation with an ageing population (and strong savings) to enjoy “better investment returns in younger, more dynamic economies abroad” (CEPR article).

The external flows also, allegedly, insulate (insure) a nation against falling domestic demand.

Whether any of these claims have validity is questionable and provides motivation for the CEPR study.

It is clear that with Germany pushing austerity on the Eurozone generally, the opportunities for investment within Europe has declined. Hence Germany’s push into China and the US.

Moreover, the German government’s obsessive pursuit of fiscal surpluses (as noted by Wolfgang Münchau above) has also created a German infrastructure crisis – “the deteriorating condition of actual bridges over the Rhine has become a symbol of crumbling infrastructure and growing domestic investment needs”.

The debate has now moved to questioning the German external investment bias.

And the CEPR Report is now providing an evidence base to allow us to assess the consequences of that bias by presenting “a comprehensive empirical assessment of Germany’s investments abroad over the entire postwar period.”

I won’t discuss the data or statistical methods used – you can read them if you are interested.

The external surpluses are mainly reinvested “in other advanced economies, especially in fellow European countries” (

almost 70%).

The results of the CEPR study are:

1. “the returns on German foreign assets are considerably lower than those earned by other countries investing abroad.”

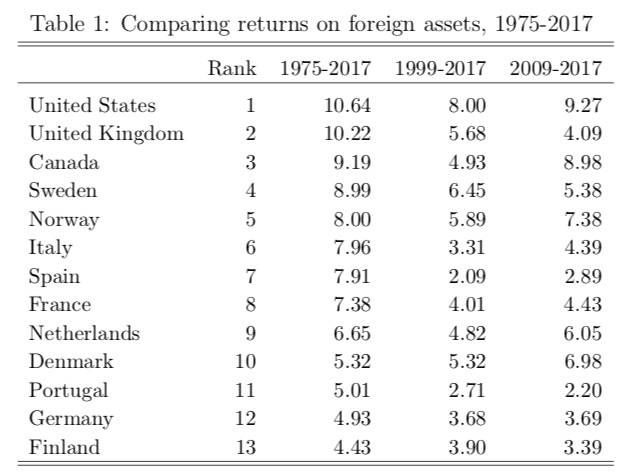

Their Table 1 (reproduced next “summarizes the main findings … Germany has the worst invest- ment performance among the G7-countries.”

2. “Since 1975, the average of Germany’s yearly foreign returns was about 5 percentage points lower than that of the US and close to 3 percentage points lower than the average returns of other European countries.”

3. “Germany fared particularly bad as an equity investor where investment returns under-performed by 4 percentage points annually.”

4. “Germany earns significantly lower foreign returns within each asset category, after controlling for risk.”

5. “Germany’s weak financial performance abroad is not merely the result of a more conservative investment strategy that focuses on safer assets.”

6. “low German returns compared to other countries also cannot be explained by exchange rate effects (appreciation), nor by the recent build-up of Target2 balances.”

7. “The valuation of Germany’s external asset portfolio has stagnated or decreased, while other countries witnessed considerable capital gains, on average.”

8. “Germany’s frequent investment losses are remarkable given that the world economy has witnessed a spectacular price boom across all major asset markets over the past 30 years.”

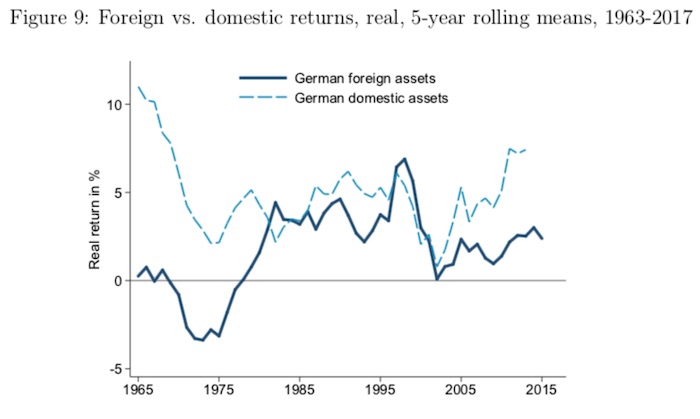

9. “German returns on foreign investment were considerably lower than the returns on domestic investment.”

This was an interesting result given my earlier comments. The following graph (CEPR Figure 9) tells the story. “On average, the difference was more than 3 percentage points”

The question then is: why does Germany invest so much abroad and neglect domestic opportunities.

10. “little evidence that foreign returns have positive effects for consumption insurance.”

This is because the “the returns on German foreign assets are more strongly correlated with domestic consumption growth than a bundle of domestic German assets”.

So that when the Germany economy is weak, the returns on German foreign assets are lower.

11. “70% of Germany’s foreign assets are invested in other advanced economies that face similar demographic risks.”

In other words, there is no intergenerational transfers evident.

The evidence is that “the share of German investments to younger and more dynamic developing countries and emerging markets has decreased rather than increased, from 25-30% in the 1980s to less than 10% in 2017.”

The CEPR report finds that “the “home-bias” of German investments in favor of European investments has intensified and the potential for demographic risk hedging has decreased accordingly” and that this tendency is “more pronounced in Germany than in other countries”.

Conclusion

The CEPR results present a comprehensive rejection of many of the shibboleths that German politicians and their industrialists hold and use as frames to bully other nations.

While “Germany is world champion when it comes to exporting savings”, the data shows that “the reputation of German household, firms, and banks of being bad foreign investors is mostly justified.”

In other words, not only is the external surplus bias damaging, in that results in a suppression of domestic spending and decaying public and private infrastructure, but it clearly is accompanied by the fact that the German financial sector misallocates Germany’s massive savings exports.

Which is one reason why Wolfgang Münchau is concerned that Germany is in danger of being left behind with an “uncertain future” as the technological revolution passes them by.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I seems the German {& French} bankers have been dumb since 2001.

According to youtube talks by Prof. Mark Blyth, the history goes something like this.

1] Before 2001 Greece and the other PIGS had a national debt denominated in their own fiat currency. The interest rates were high because of the risk of default.

2] In about 2001 they joined the EU & EZ. So, their national debts were re-denominated in euros.

3] Neo-liberal theories caused the bankers to forget that there was still risk of default by Greece and other PIGS nations. During the good times from 2001 to 2007or8, German and French bankers bought up all the Greek and PIGS bonds that were for sale. I assume the sellers were mostly people and corps. {banks?} of the nation who had sold the bonds. This meant that German banks were lending money to the ex-bond holders and expecting the nations to repay the loan down the road. They did this because the high interest rates looked very attractive. They thought there was little risk of default because the Great Moderation meant that the business cycle no longer would happen. And the nations were now part of the EU & EZ and so would not default.

. . From 2001 to 2007 this flow of euros into Greece allowed it to buy products from Germany. This made the German economy seem stronger than it was, since it was accumulating foreign assets in exchange from real things {cars?} and those foreign assets had little real value. Little value unless the ECB somehow paid those bonds, even though this was/is forbidden.

4] Along comes the GFC/2008. Suddenly nobody is lending money to anyone for any reason, no matter how good a risk they were. Everyone was afraid that all banks might fail. Now the Greek Gov. can’t refinance the bonds coming due.

5] The German bankers realized that Greece might have to default. They put huge pressure on the ECB to not let the Greek Gov. default. The ECB sided with the banks over the PIGS nations and worked to force the Greek Gov. to take out a loan from the IMF that everyone knew could not be repaid. The new Greek Gov. caved in and took out the loan. But, the Greek Gov. didn’t get the money, instead it was sent to the German and French banks to bail them out from the stupid decision that they had made to buy those high interest “low default risk” Greek bonds, buy them from people who had bought them years ago before Greece joined the EZ.

6] Note the stupid bankers being bailed out.

7] Now, the ECB is still turning the screws on the Greek people who had nothing to do with the cause of the mess. They didn’t own the bonds, they didn’t sell them to German bankers, they aren’t German bankers, etc., and yet their lives are being ruined.

The Greek Finance Minister says on youtube that —

. . a] Several player admitted to him that they knew that that IMF loan could not be paid by Greece no matter what it did. They just kicked the can down the road because their skin in the game was make whole and it was the Greek people who were going to get skinned. This is evil to me.

. . b] That he had a program in the works in the Finance Ministry to use computers to catch Greek tax cheats and make them pay what they owe. However, as part of the loan agreement, this program was forbidden. It was to be dismantled. This shows that all talk about how the Greek people let the Greek Gov. {for many ears} let the rich Greek people avoid paying their fair taxes IS just BS. The IMF sided with the rich Greek people so they could continue to not pay their taxes. So, it is BS that the Greek people need to be punished for letting their Gov. be lax in collecting taxes. The IMF is now to blame for the Greek Gov. not having the revenue it needs to make payments on the loans. {Not that the Greek nation can pay 68B euros back in any case.} {68B euros is IIRC the amount of the IMF loan.}

@Steve_American

Your ref. 1. “….high risk of default”

No I would instead say high risk of continous devaluation of sovereign currencies. In the greek case just look at Turkey that has overtaken a large part of the Greece economy due to the Euro-prison.

Best regards

I have difficulty assessing how one distinguishes between financial asset prices and real values, in terms of productivity. I also recall that Keynes, during his work on the Versailles Treaty, noticed the difficulty in suppressing domestic wages and prices compared to adjusting prices between countries. This was when each country had its own currency. All that aside, Germany’s experience indicates a need to re-evaluate the relative returns between domestic investment and foreign investment.

As a layman, I am a bit confused.

Are German industrialists doing this out of their own individual interest?

Are they doing it because of economic nationalism?

Why are they kneecapping themselves with these awful investments abroad?

Are these questions better suited to geopolitics rather than economists?

Is there a method to this madness?

Take a look at Greece “Economic statistics” in the bottom of the following link:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis

Before 1995 (EU enlargement) greek government debt was low. Compared to i.e Turkey foreign debt has been very low. Look also at greek GDP deflator before 1995. Inflation, inflation…… .

Greece had its golden years in the 70s when tourists started charter-travelling which also opened up some other exports opportunities.

Of course there is also some default-risks involved but as we know sovereign debt at floating currency-rates can always be paid back if the government choose to do so. Foreign debt is another story which the turks understands incl IMF ()

Germans are not so good as earning money in their sleep as the rest of the world =).

Hi Bill,

So I have to be moderated nowadays? Is that because of my opinion regarding MMT and the GND?

I am in favour of many of the proposals in the original GND manifest. But I have serious doubts about creating large deficits regarding certain green-investments that are not grounded in cost- benefit analyses.

Such schemes could bite the MMT reputation in the future for which I would feel sorry about.

Best regards

Before MMT enlightenment, I use to picture Foreign Investment as a ‘bundle of new money’ arriving in the local economy, from overseas.

But now I wonder if the operational reality is that Foreign Investment is essentially just a foreign exchange transfer – meaning no new bundle of money arrives – rather, just the shifting of funds between local accounts.

So, the question is, what does Foreign Investment actually ADD to the economy – that isn’t already there? Or is it effectively just a foreign exchange transaction?

Would welcome clarity on this.

Hi Bill Wong,

The way I understand it is that the money will still be in German currency (Euro) initially. If an American company being invested needs to buy things with the money, then the bank must be instructed to get the currency by foreign exchange depend on what currency the vendor wants. Initially, however, the funds would be sitting in a ledger in a USA branch of the German bank where these funds are displayed on an electronic record.

Considering the company would probably buy USA dollar goods, Euros will probably be used to purchase US dollars.

Then, depending on vendor, it will go down and an account of a vendor goes up after a sale or hiring.

I think you are absolutely right regarding money shifting in local accounts in USA in my example.

FDI is absolutely adding to the economy by employing labor and purchasing goods! (assuming the investment not used to load up people with debt). Its why when we consider the economy sectoral balance, we always have foreign sector export as adding to the economy.

Of course, the question is does it really transfer to the poorest still stands.

Someone please correct, this is just how i think it will work.

Bill Wong @1:10,

I think a lot depends on just what the foreign investment actually is purchasing. It is going to add to demand in the local market for those goods or labor or property that the investment is spending into. So it isn’t just a foreign exchange transaction.

“So, the question is, what does Foreign Investment actually ADD to the economy – that isn’t already there? ” It adds to spending and therefore local income (assuming the investment spending is directed at local sellers), at least for a time. That could have good or bad consequences. Or could be good for some and bad for others.

I think MMT would say that adding to demand is something that is always possible for the currency issuing nation. But it might not be possible for a locality within that nation to achieve.

@Bill Wong

If you invest your german euros in i.e the US stockmarket your bank in Germany would sell you the corresponding dollars against your euros. Your bank will normally settle its dollar-account in the market. The nettransactions is cleared by the ECB and US FED and can change outstanding dollar-reserves at the ECB. Still your buy is a flow of new dollars into the us stockmarket but as you know there is a seller for each buyer which means the market value of dollars is affected, not necessarily new dollars outstanding. Apart from placing dollar-reserves into interestbearing federal us bonds every centralbank has its own account at the NY Federal Reserve. The balance is changing depending on trade and investments and loans etc.

When german banks (Deutche) financed the us subprimes in the years of 2002-2007 they had subsidaries in the US that funneled large german savings (credits) into the us banking system and subprime-market. Selling those toxid assets also means financing other banks needs of credit against real estate buyers but also financing trading and investments in those assets between financial actors, pensionfunds and banks. This money was growing in a long term falling interest-rate environment were the interbank-liquidity and repo-market (rehypothecation) was exploding. Part of that was because of the german/franco so called money wholesale-process. Large US credits against european collateral (cross-border lending) and includes the shadow banking system. I recommend reading Claudio Borio’ s research at the BIS instead of believing former fed chief Bernanke’s false claim about the involvement of the “chinese savings glut” (large dollar reserves). Chinese investments in the US I think increased more after the GFC due to deregulations.

Deutche Bank was one of the perpetrators selling us subprime from London City (together with british and us banks 1 trillion dollar) to Irish and German customers (savingssbanks like the large regional Landesbanks).

1 trillion for Germany, 1 for the US and 1 for the other parts of the world. London City from were the sellers flocked!

Dear Thorleif (at 2019/08/20 at 1:05 am)

Read the rules regarding comments. You put a link in the comment and I always monitor links. Nothing to do with you personally or your views.

best wishes

bill

Nicholas. Yes. There is method to the madness. The wealthy and the powerful see no advantage to sharing with fellow citizens or employees. Letting people work for their own benefit runs against their guts. Even if it means not letting the wants and needs of the domestic population determine and drive domestic economic growth. They want to use their efforts to build up financial claims and acquire real assets in other lands rather than share.. It means there is a high level of inequality in Germany. With capitalism it always ends up as “Beggar thy Neighbor” and an exhaustion of demand.

Dear Bill,

So I understand. You check every link as a standard policy. Maybe I never posted a link in my posts before or in recent times. I am sorry I did not check before my 1:05 post above.

Best regards

You gotta love the Germans

Their households save and the government does not spend. So they sell the excess production they can’t consume at home to their neighbours who they then punish for running a trade deficit with them!

It’s not a virtuous circle is it?

@ Bill Wong

Remember Bill’s model on Sectoral balances?

How is money created?

1. Bank credit money (for every debt there is an asset) is a grossexpansion in the private sector “out of thin air”.

2. Centralbankmoney ( sometimes out of thin air) also named high powered money usually means open market operations. They can also create new money through i.e QE or do asset/debt swaps (portfolio-management) with banks as part of monetary policy. Bond-auctions with the Treasury is an example of debt swaps from centralbank to treasury balance-sheets changing bankreserves and debt-durations.

3. Treasury-deficits is new net money/financial assets for the private sector without any corresponding debt in the same sector.

4. Foreign sector. All outstanding dollars outside of USA have originated from dollars created in the USA. There is though a large so called euro-dollarmarket outside the USA. This market is within the international banking-system. Dollars floats in and out of USA (through the exchange-mechanism) but the number of nominal dollars outstanding can only change through 1-3 above. The US Federal Reserve can always extend dollar-loans to “customers” inside or outside the USA. During crises like the GFC this is standard operation to avoid financial armageddon.

By monetary controls governments can manage the economy and avoid i.e booms/busts. If they want!!!

Smaller countries or developing ones normally need some capital-controls to avoid that their “cheep” assets are sold out at a bargain.

Thanks to @Tom, @Jerry Brown, and @Thorleif for responding to my question on Foreign Investment.

Helpful explanations, much appreciated.

@PhilipR

Yes their Weimar-scare really sits in their dna, their bone&soul. I lived in the southern “poor” Bavaria for a few years and saw the public complaints from my eyes and ears. It is a divided country. Even the workers in the industrial A-team is risking future losses. Bill is right on spot with his claims. But the conservative industrial elite is forming the national policies within the EU together in an unhealthy symbiosis with the only 25 year old neoliberal banking-elite in Frankfurt et al. The german automobil cluster is enormous and if, I say if they will fail to grow or at least maintain their middle class and increase private consumtion…….then Houston…..

The rich EU-countries can brake the EU-rules but……

I’m now in the curious position of simultaniously being worried about my future employment when the sh*t hits the fan and finally being able to spread some “I told you so” amongst friends and colleagues.

My words to them, for those of you who speak a bit of German:

“In diese Krise haben wir uns selbst hineingespart.” (We saved our way into this crisis.)

Still, a depressingly high amount of the people here think it was somehow the PIIGS that are at fault and that if anything Schäuble simply wasn’t hard enough on them. I kid you not.

Am I wrong to have put all my hope into the Sanders campaign across the pond? Could that move the Overton window in regards to fiscal policy in Europe? On the other hand, I’m under the impression that even as the IMF has stopped encouraging the beatings, the remaining troika goons are happy to provide an encore. It’s almost as if the beatings themselves are the point and could go on without IMF/World Bank backing.

I had always been little skeptical about Münchau, he either doesn’t really get it or he is just afraid to rock the boat too much. A bit krugmanian, if you ask me. But then again, given the amazingly mainstreamed media landscape in Germany*, one has to be thankful for any sign of a non-conformity with austerity dogma.

*We wouldn’t have a major Nato-critical network if it wasn’t for RT’s pro Kremlin stance. Might be a bit of recency bias on my end, but anyone who speaks German might find Daniele Ganser’s research on the workings of mainstream German media thought provoking (his other work on illegal wars is a masterpiece in commen sense and decency imho). I thought of myself as an informed individual. Turns out I’m not.

Cheers!

@HermannTheGerman (Wednesday, August 21, 2019 at 0:37),

Re: Sanders: For sure he must know MMT theory very well (since he had Stephanie Kelton as an advisor). How far his actual policies would allow for full-on deficit spending when it came to the crunch, I’m really not sure. I have read a citation of him in which he is supposed to have said something like “I have always been a balanced budget sort of guy”. (Apologies if I am misquoting him or mis-remembering). As so often, we will have to wait and see.