The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The German model is not workable for the Eurozone

I had an interesting meeting in Melbourne yesterday and the topic of the discussion, among other things, was the propensity of the current economic malaise in Europe to invoke associations with its historical past – in particular, the rise of the ugly German. In my blog earlier this week (January 30, 2012) – Greece to leave the Eurozone and become a German colony – one might have been tempted to conclude that I was invoking memories of the Germany’s annexation of Austria (the Anschluss). I even used the word Teutonic – a rather old-fashioned term for Germanic peoples (broadly) – in the phrase “My how audacious our Teutonic friends have become!”. This was in a discussion about the leaked German document which urged the EU Summit on Monday to effectively put Greece into receivership. But in fact, what I have been at pains to bring to the public debate is not an urging that we construct the current nasty statements from German politicians and its press about lazy Greeks etc in terms of these historical enmities but rather see them for what they really are – deeply flawed macroeconomic reasoning. A thorough understanding of macroeconomics would lead to the conclusion that the German model is not workable for the Eurozone. It will not help Germany nor anyone else. It is a deeply flawed economic doctrine that reflects the same neo-liberal ideology that led to the the original design of the European Monetary Union. Whether the “ugly German” is also implicated is another question altogether.

The European Project was largely about detente after two very fracturing wars and lots of smaller disputes in the C20th. Somehow, by creating a political union the historical enmities would fade – and cordial relations could be fostered. It was an extension of the logic that led to the earlier (1904) Entente Cordiale between the French and the British which ended their long history of military conflicts.

It was logical that the EU would also seek to harmonise certain economic parameters as a way of working together for the betterment of all. The result was that during the Post-WW2 period, the sense of deep antagonism towards the Germans was actively discouraged and Germany grew out of the wreckage that they had wrought on themselves and the rest of Europe to be a strong economy.

It is impossible to eliminate the historical antagonism but through education, a more sophisticated, more nuanced appreciation of concepts such as cultural stereotypes and ideologies can be obtained and that was the European agenda in the 1960s and beyond.

But the EU elites decided to go one step too far when they decided to impose the monetary union on the vast majority of nations in the region. For this exercise was driven by a different sort of ideological stereotype – one that spans many cultures – neo-liberalism. It just happened that the Germans had cultivated their own brand of extreme neo-liberalism which is known as ordoliberalism.

The aim of the designers was to firmly limit the capacity of the “state”. I wrote about the influence of ordoliberalisms in this blog – Rescue packages and iron boots.

Ordoliberals are free-market liberals but not free-market libertarians in the Austrian-school sense. As an example, the Austrians advocated a non-intervention approach to the current crisis on the basis that all government growth is undesirable and will delay the market resolution. The ordoliberals argue that the government is largely to blame for the crisis (by not allowing competition to work properly) but that government support in the crisis was necessary given the scale of the downturn. But both free-market camps are obsessed with the notion that the patient, now probably saved by the emergency public interventions, needs to be weaned of its drug dependency.

The upshot was that the Germans started to throw its weight around again in the discussions that led to the establishment of the European Monetary Union.

It was obvious that during the Maastricht process the neo-liberal leanings of the designers were never going to allow a fully-fledged federal fiscal capacity to be created, which would have allowed the EMU to actually effectively meet the challenges of the asymmetric aggregate demand shocks that the crisis generated.

Instead they wanted to limit the fiscal capacity of the state in the false belief that a self-regulating private market place would deliver the best outcomes and be resilient enough to withstand cyclical events. The Germans, of-course, knew that by signing up to the EMU they would have to change the way they pursued their mercantilist ambitions.

Previously, the Bundesbank had manipulated the Deutsch mark parity to ensure the German export sector remained very competitive. That is one of the reasons they became an export powerhouse. It is the same strategy that the Chinese are now following and being criticised for by the Europeans and others.

Once the Germans lost control of the exchange rate by signing up to the EMU they had to manipulate other “cost” variables to remain competitive. So the Germans were aggressive in implementing their so-called “Hartz package of welfare reforms”. A few years ago we did a detailed study of the so-called Hartz reforms in the German labour market. One publicly available Working Paper is available describing some of that research.

The Hartz reforms were the exemplar of the neo-liberal approach to labour market deregulation. They were an integral part of the German government’s “Agenda 2010″. They are a set of recommendations into the German labour market resulting from a 2002 commission, presided by and named after Peter Hartz, a key executive from German car manufacturer Volkswagen.

The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schroeder government and introduced in four trenches: Hartz I to IV. The reforms of Hartz I to Hartz III, took place in January 2003-2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005. The reforms represent extremely far reaching in terms of the labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The Hartz process was broadly inline with reforms that have been pursued in other industrialised countries, following the OECD’s job study in 1994; a focus on supply side measures and privatisation of public employment agencies to reduce unemployment. The underlying claim was that unemployment was a supply-side problem rather than a systemic failure of the economy to produce enough jobs.

The reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market (so-called mini/midi jobs) and there was a sharp fall in regular employment after the introduction of the Hartz reforms.

The German approach had overtones of the old canard of a federal system – “smokestack chasing”. One of the problems that federal systems can encounter is disparate regional development (in states or sub-state regions). A typical issue that arose as countries engaged in the strong growth period after World War 2 was the tax and other concession that states in various countries offered business firms in return for location.

There is a large literature which shows how this practice not only undermines the welfare of other regions in the federal system but also compromise the position of the state doing the “chasing”.

But in the context of the EMU, the way in which the Germans pursued the Hartz reforms not only meant that they were undermining the welfare of the other EMU nations but also droving the living standards of German workers down.

And then the crisis emerged amidst all this.

The upshot is that while the monetary union is unworkable, the way the Germans are now behaving is endangering the political gains that were made in the Post-WW2 period.

As the Germans lead the persecution of ordinary Greeks (soon citizens of Portugal will feel the edge and the Irish walked the plank before being told to), the anti-German sentiments are mounting and appealing, increasingly to the old historical stereotypes.

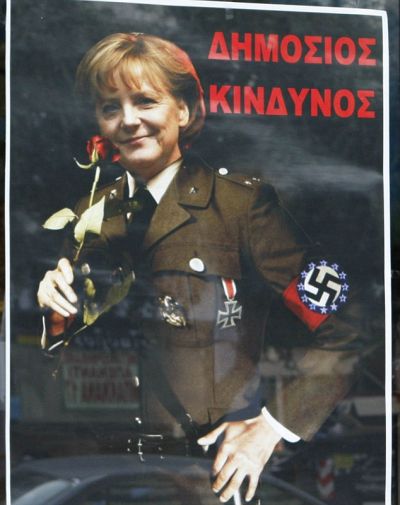

We have all seen the images that are now emerging from the coverage of the Greek protests, for example. But the sentiments expressed by the Greeks are being mirrored throughout Europe now.

The use of the Swastika, despite its long (non-nazi) history, is very pointed in the context of Greek protests against perceived German oppression.

The German words on the placard – Unsere sklaverei gibt euch die freiheit – translates broadly to “Our slavery gives you freedom”. Apparently, the protesters were chanting “no to a fourth Reich”.

The posters became obviously personal and associative in other material produced by the Greek protesters. The words on the Merkel poster – ΔΗΜΟΣΙΟΣ ΚΙΝΔΥΝΟΣ – mean public risk.

My view as a non-European but as someone with an obviously European heritage (and culture) is that the protest movement should avoid these historical associations and, instead, develop an economic critique of the situation that points to the unworkable nature of the EMU.

There was an interesting article in the English-language version of Der Spiegel (August 12, 2011) – Merkel Is Leading the Country into Isolation – which carried the sub-title “The Return of the Ugly Germans”.

It is interesting not only for its content but also the fact that it was written by a German, which means that it cannot be dismissed as Greek hysteria or the opinion of an outsider who doesn’t understand Germany or is jealous of its “success”.

The author, Jakob Augstein says that:

The German bogeyman has raised its head yet again in the euro crisis. Merkel’s rigorism is ruining the work done by generations. Even if the chancellor is correct in her policies, it would be better for Germany to do the wrong thing together with its partners than to go it alone and insisting on the right thing.

The point is that Merkel’s “rigorism” is, in economic terms, the “wrong thing”. So Germany could actually reinforce the good work it did in the 1960s and 1970s by working with Europe rather than against it by renouncing austerity.

It would do everyone a favour.

By insisting on this austere approach when it is patently the wrong approach to take it is not only damaging itself economically but also inviting a return to those who want to focus on the “ugly Germany” rather than understand that nation to be a complex intermingling of various characteristics.

Jakob Augstein says that:

German nationalism was first sired 200 years ago. It is a dangerous beast that has brought about suffering and horror. We thought it had been eliminated, but it has once again emerged from the shadows in this major European crisis.

He cites a member of Merkel’s CDU party who apparently said “Now Europe is speaking German”. He also notes the reaction from neighbouring countries along the lines depicted in the posters/placards above.

Jakob Augstein concludes that:

Just two decades after German reunification, Europe has already reverted to its postwar stereotypes about Germany. From the German perspective, the worst possible scenario has come to pass: The Ugly German has returned.

He notes the case of a conservative German journalist comparing the “net payments made by Germany to the European Union … to the reparations payments made after World War I.”

All of this is dangerous because it conflates the historical associations with the economic events of today in a way that is unnecessary. Even if the Germans could be stereotyped in this way, there are better more compelling arguments that can be made to attack the current “German” position on the crisis (as expressed by their political leadership).

Whether the current behaviour by the political elites in Germany reflects a tendency by the “German nation” to want to create Europe in its own image/ethnicity as in the past or dominate other nations through annexation etc, is one consideration which I will leave to cultural anthropologists, historians, political scientists etc.

But when journalists (quoted by Jakob Augstein) write that Germany is finally “learning to lead” and note before time and the political leaders are “insisting that their Continental partners should adopt Germany as their model” there is a simpler critique.

It is the wrong model.

As the title of this blog says – the German model is not workable for the Eurozone.

Jacob Augstein also blames the tendency to conflate the tensions surrounding the crisis and the historical antagonisms squarely on Merkel and her party.

He says:

Indeed, this chancellor is dangerous. Her abrasive pro-austerity policies threaten everything that previous German governments had accomplished since World War II. And the new German realism — which is idiosyncratic, cold and gaining traction among some media outlets — supports her as she pursues this risky course.

To find evidence that this austerity approach doesn’t work to satisfy the broader goals of a modern Europe we don’t have to go to Greece. We can just study contemporary Germany.

Jacob Augstein discusses Germany’s “internal divisions” and the “huge swaths of former East Germany having been left to anti-democratic and pro-neo-Nazi sentiments” and the widening “chasm between the haves and the have-nots in our society”, which the Hartz-type austerity have bred.

Which then brings us to the current proposals for a new EU Treaty.

The EC released a statement (January 30, 2012) – Agreed lines of communication by euro area Member States – which said that:

The Treaty on stability, coordination and governance in the Economic and Monetary Union has been finalized. It will be signed in March … This represents a major step forward towards closer and irrevocable fiscal and economic integration and stronger governance in the euro area. It will significantly bolster the outlook for fiscal sustainability and euro area sovereign debt and enhance growth.

They also released the proposed – Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union – which will form the new fiscal compact.

Reading this document in print – after having previews of it in the press statements etc – is something else. It becomes serious. To think that some high-paid, presumably employment-secure bureaucrats, all with tertiary educational qualifications could come up with something as abjectly woeful as this is a stunning indictment of the narrowness of human perspective.

Article 3 details the Fiscal Compact that the countries will sign up for. It is like signing up to walk off a plank overlooking the Grand Canyon.

We read:

1. The Contracting Parties shall apply the following rules, in addition and without prejudice to the obligations derived from European Union law:

a) The budgetary position of the general government shall be balanced or in surplus.

b) The rule under point a) shall be deemed to be respected if the annual structural balance of the general government is at its country-specific medium-term objective as defined in the revised Stability and Growth Pact with a lower limit of a structural deficit of 0.5 % of the gross domestic product at market prices. The Contracting Parties shall ensure rapid convergence towards their respective medium-term objective. The time frame for such convergence will be proposed by the Commission taking into consideration country-specific sustainability risks. Progress towards and respect of the medium-term objective shall be evaluated on the basis of an overall assessment with the structural balance as a reference, including an analysis of expenditure net of discretionary revenue measures, in line with the provisions of the revised Stability and Growth Pact.

c) The Contracting Parties may temporarily deviate from their medium-term objective or the adjustment path towards it only in exceptional circumstances as defined in paragraph 3.

So balanced or in surplus in structural terms (which presumably means that the cyclical deficits can be well above the 0.5 per cent.

Rapid convergence.

Exceptional circumstances – “refer to the case of an unusual event outside the control of the Contracting Party concerned which has a major impact on the financial position of the general government or to periods of severe economic downturn as defined in the revised Stability and Growth Pact, provided that the temporary deviation of the Contracting Party concerned does not endanger fiscal sustainability in the medium term”.

Which if I was a lawyer I would say is a set of notions that have no substantive meaning. What is rapid? What is unusual? What is temporary? When is something outside the control of the Contracting Party? When is a term a medium term? What is fiscal sustainability?

In economic terms this Treaty describes a set of rules that even in good times will present difficulties but in bad times will be simply unworkable. They will be handing out fines and penalties to every nation.

But the Treaty has “Germany” written all over it. While it might be tempting to then stereotype that “ownership” and draw long historical lines about a rigid society that has this or that characteristic and at times has been dangerous and ultimately destructive, a much simpler, although less easy to grasp critique is sufficient to generate opposition to it.

It is not even in Germany’s best interest overall (excluding the elites) to have this Treaty.

The German model is not workable for the Eurozone including Germany. It might be the product of elites in Germany totally obsessed with ordo-liberalism and consistently acting out some historical penchant for being “ugly”. But it is better for educational reasons to provide a pure economic critique.

As a set of guidelines for a modern monetary system the Treaty is nonsensical. It would be better for the Greeks et al. to march in the streets with placards such as regular reader Matt brought along to the Washington Teach-In Counter Conference on April 28, 2010 which he is modelling with Warren Mosler in the following picture.

In the context of that poster – depicting the sectoral balances, which are derived from the National Accounts of a nation, it becomes obvious very quickly that the provisions of the proposed Treaty are unworkable.

To refresh your memory about how the sectoral balances are derived you could read this blog – Norway and sectoral balances – among many.

By way of summary (as in the poster), the following accounting statement has to hold at all times.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

The symbols (alphabetical letters) refer to Total private saving (S) – which is the difference between total spending and disposable income; total private investment (I); total government spending (G), total government taxation revenue (T), and net exports (X – M), where X is exports and M is imports.

So the three sectoral balances (the terms in brackets) have to sum to zero at all times.

You can also write the accounting statement in this way (which makes it easier to understand for some):

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (S – I) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit. A deficit means the private domestic sector is spending more than its income and vice-versa.

- The Budget balance (G – T) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus (as written). A deficit means the government is adding net financial assets to the non-government sector and vice-versa.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit. A deficit means that the external sector is draining domestic demand (spending) and vice-versa.

For the left-hand side of the equation to be positive (that is, the private domestic sector is running a surplus overall) then the sum of the budget and external balances must be positive (and equal to the left-hand side).

Should the external sector be in deficit (X < M) by say, 3 per cent of GDP, then if the private domestic sector is to save overall then the government sector would have to be in deficit (G > T) of, at least, 3 per cent of GDP.

So you immediately see what is wrong with imposing a balanced budget rule on the whole EU region as a matter of law dictated by Treaty.

Eurostat publish Statistical Yearbooks on trade – the latest (published December 15, 2011) – External and intra-EU trade – A statistical yearbook – Data 1958 – 2010 . It is a 410-page tome, which should satisfy your desire for methodology, concepts and data.

The Euro area current account balance in November 2011 was

The ECB reported that:

In November 2011 … the seasonally adjusted current account of the euro area recorded a deficit of €1.8 billion in November 2011 … This reflected a deficit for current transfers (€11.4 billion), which was partially offset by surpluses for goods (€4.9 billion), services (€4.2 billion) and income (€0.3 billion)

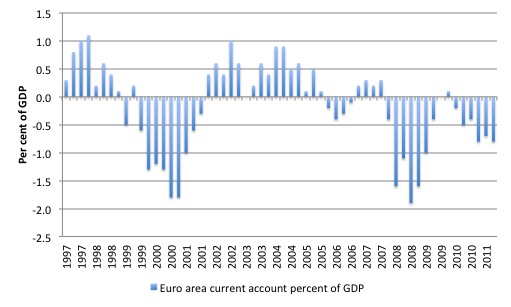

Since the first-quarter 1997, the Euro area has recorded an average current account deficit of 0.16 per cent of GDP. Effectively a balance of zero (Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators).

The following graph shows the history – small deficits, small surpluses as exports grew, then small deficits again as exports has declined.

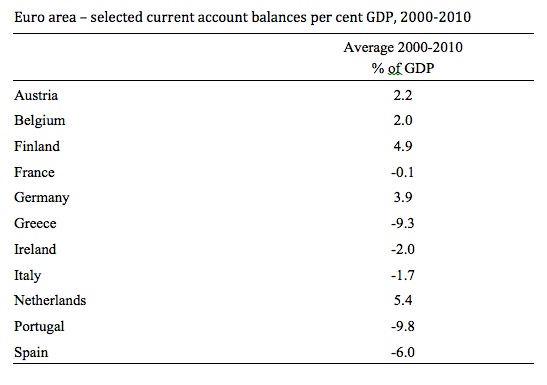

But within the Euro area there are dramatic differences in the external balances. The following Table shows a selection I computed (from OECD MEI data).

It might be easy to jump on the bandwagon and note that the nations in most trouble at present are those with large current account deficits. But one has to also understand the interdependency between the surpluses and the deficits, in a region that has high intra-trade flows (more than 60 per cent of all Euro area trade is internal).

Austerity will reduce the external deficits of the Southern European states but will also undermine the export revenue of the Northern States. Austerity also undermines the domestic demand in all states.

The German model is to run large current account surpluses and that relies, in no small way, on other EMU states running external deficits.

The point is that if all nations are trying to run balanced budgets or surpluses then those that run current account deficits will also have private domestic sectors that are spending more than they are earning (and accumulating increasing indebtedness).

That is not a viable growth strategy because the private domestic sector balance sheet cannot accumulate ever increasing levels of debt indefinitely.

Germany could reduce its external ambitions and instead promote domestic spending-based growth. But that would also be inconsistent with the Treaty push relying on constant austerity.

The expectation will be that most nations will be in continual breach of the Treaty rules but by trying to maintain their aggregates in accordance with the Treaty they will inflict a harsh deflationary bias on their domestic economies.

As the IMF Official said the other day (see UK Guardian) in relation to the capacity of nations to tolerate damaging austerity, that:

… social tolerance and political support have their limitations

I will come back to this in later blogs.

Conclusion

An essential requirement for an effective monetary system is that the citizens have to be tolerant of intra-regional transfers of government spending and not insist on proportional participation in that spending. The other side of this coin is that a particular region might enjoy less of the income they produce so that other regions can enjoy more income than they produce.

To achieve that tolerance there has to be a shared history which leads to a common culture. Language is an aspect of this but not necessarily intrinsic.

People in NSW and Victoria (states of Australia) might complain that the smaller state of Tasmania gets a disproportionate amount of government assistance relative to its “tax base” which invokes the claims that some Australian states “subsidise” others but when it comes down to it there is no serious discussion that our system of federal transfers should stop or that we should make the weaker states pay their way.

Interestingly, the perception of which Australian states are subsidising other states has changed over time as the relative fortunes of the states has changed with the evolving pattern of industrial composition. So the manufacturing powerhouses of NSW and Victoria are now not as influential as they were and the primary commodity producers like Western Australia are more powerful despite their smaller population.

But the point is that an effective federal system has to share common elements to ensure that the macroeconomics of the monetary system dominate more regional concerns. That capacity is non-existent in the Eurozone.

We don’t have to invoke the historical national stereotypes to know that the German model is not workable for the Eurozone.

Keeping the message going

I probably brief journalists 3-4 times a week. Sometimes they quote me other times not. Here is an example of when they do – Government urged to ditch surplus to protect jobs.

Saturday Quiz

As an aid to public education (and fun) the Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow – with some tricks to occupy your attention for at least 5 minutes.

That is enough for today!

Good points on fiscal transfers.

If the Euro Area moves toward a higher integration it would need a central government which is transferring fiscal resources and these payments may be substantial. So Germans tend to think that it is going out of their pockets and they will have lower incomes. What they don’t realize is as a result of a more integrated Europe, their quality of life will be better and so would be their incomes. So they would end up having higher incomes both pre-tax and post-tax compared to the present case.

The “taxing Peter to pay Paul” rhetoric is an exogenous money fallacy.

There are some economists such as Charles Goodhart realize that while the European Parliament has more role in non-breakup scenarios, they think there should be a 2% budget or whatever. Which is obviously wrong.

Europeans can take comfort with the fact that there are more than 1,000 languages recognized by the Indian Census and the culture is more diverse across the whole nation than what it is within Europe. So it should be an inspiration for them.

Europe needs a Vallabhbhai Patel.

Sectoral balances are not my strong point, but I have a problems with the equation displayed by Warren and Matt. First, there is no clear distinction between investment goods and consumption goods. I.e. is something expected to last one month an investment? What about one year, three years….?

Second, even if you can define investment, money spent by one person on investment is someone else’s income. Thus the investment term (I) is irrelevant, seems to me.

So I suggest the equation be S = (G – T) + (X – M), where S is “net saving” – i.e. the net rise in the private sector’s stock of money.

P2 of the proposed new treaty doc says there is an “obligation to transpose the ‘Balanced Budget Rule’ into national legal systems through binding and permanent provisions, preferably constitutional’ (subject to the jurisdiction of the European Cout of Justice).

So, something that is designed to shackle a (euro areas) goverments ability to react positively to (future) severe economic conditions (e.g. a demand shock) will now be enshirned in (domestic) law. Goverments will be presumably challenged in their own courts should they try to save the skins of the people they represent.

I sincerely hope that is is true, that “…social tolerance and political support have their limitations”. We are in or some hard times if it is not.

It’s a bit upside down but to have fiscal transfers in a federal system you must also establish that the federated states can’t unilaterally award themselves whatever they want, as they could up to now de facto, so you need this. Ideally you’d setup this and the federal treasury at the same time but it’s not the way european construction operates. The fed treasury will come later when it is clearer to everybody that it’s necessary be it in six months or in a couple of years. Wait and see and all will be fine.

Arguably it makes a less sexy story than outright fear mongering.

Dear Bill

Angela Merkel is a physicist. How come she doesn’t understand something as obvious that not all countries can run a trade surplus, that if some have a trade surplus, others must have a trade deficit. Merkel is also is also fond of saying, “Die Welt hat über ihre Verhältnisse gelebt” = The world has lived above its means. That’s another absurdity, unless the world has been consuming stored goods.

Regards. James

“First, there is no clear distinction between investment goods and consumption goods. ”

That’s because those are generally real concepts, not nominal. In real terms simply declaring something as being included in ‘I’ creates the equivalent ‘S’ instantly.

Consumption is defined as what is left over after the household sector has saved/borrowed (which we can measure) and paid taxes (which we can measure) out of their income (which we can measure).

So you get Y = C + S +T for the households

The other equation is Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

G and (X-M) we can measure.

The C in the second equation is taken to be the same as the one in the first equation, which makes ‘I’ the balancing item for the equation.

I take ‘I’ to be a sort of nebulous concept relating to how effective banks have been at lending money to entities other than households. It’s the wobbliness of I in a nominal sense that seems to occur as a consequence of the endogenous nature of money. It seems to be more loosely related to the concept of ‘investment’ than it is in the loanable funds model world.

That’s roughly the model I have in my head. I may be completely wrong of course.

“If the Euro Area moves toward a higher integration it would need a central government” (Ramanan)

In which language will the head of such central government speak to the citizens of the Euro Area?

Any suggestions?

As a German, and from my experience talking to other Germans, the biggest problem over here is the inflation phobia. To the average German mind, any kind of government deficit immediately leads to 1920s style hyperinflation – this is where any argument suggesting an alternative approach for the Eurozone always leads. I and others are constantly trying to convince people otherwise, but it’s a very slow and tedious process.

In a way, Germany is again “attacking” the rest of Europe as a late consequence of the Treaty of Versailles. Not that that’s a valid excuse, of course, but the irony should be appreciated.

The fed treasury will come later when it is clearer to everybody that it’s necessary be it in six months or in a couple of years. Wait and see and all will be fine.

If we wait any longer, it will be anything but fine.

Bill,

Thanks. This post is a another good reminder that economic policy is better designed with logic than popularist dictates. In the case of Merkel’s rigorian chant, its chords of “deeply flawed macroeconomic reasoning” are rooted both in the most basic fallacy of composition regarding cross-border trade and in cultural/ideological stereotypes. My only question is: Why isn’t everyone labeling this particular episodic policy mistake as “Merkelantism”?

James Schipper: “Merkel is also is also fond of saying, “Die Welt hat über ihre Verhältnisse gelebt” = The world has lived above its means. That’s another absurdity, unless the world has been consuming stored goods.”

Stored goods like oil?

Dear Min

I wasn’t thinking of oil but of man-made goods. The only way in which the world as a whole can live above its means in a given period, that is, consume more man-made goods than it produces in that period, is by consuming goods produced in earlier periods and which haven been stored.

Let’s suppose that the world only produces grain. By not eating all the grain harvested in 2005 – 2011, for instance, the world can in 2012 eat more grain than it harvests this year.

Of course, it is impossible for the world in 2012 to eat grain that will be harvested in future years because production has to precede consumption. This impossibility completely undermines the argument that we can rob posterity by living beyond our means. What normally happens is that some people live above their means and others live below their means. The two amounts are exactly the same, just as receivables and payables are talways he same for the world as a whole.

Still, I think that you have a valid point in that consuming a non-renewable resource like oil is a way of living beyond one’s means and also possibly a way of robbing future generations. Fossil fuels are a natural inventory, and running down an inventory means that there is less to consume in the future.

Regards. James

Since I am not an economist but a german citizen, I’d like to point out another major concern about the resurfacing of the “ugly german”.

Unfortunately, the majority of the german people and the german mainstream media do not share your views on the true nature of the eurozone crisis at all. The german governments over the last decade have been telling voters that neo-liberal austerity measures where crucial to maintaining competitiveness of the german economy in the face of rising globalization and they have been very successful in influencing public opinion in that way.

As a result, the majority of germans now firmly believe that they were in fact the only ones doing the ‘right thing’, as opposed to the southern eurozone members, who germans now regard as lazy, inefficient profligates who don’t know how to conduct a proper business.

Beside the fact that Angela Merkel’s policy towards a solution of the crisis is certainly extremely short-sighted and borderline insane from a macroeconomic point of view, it caters at the same time to the overall belief of the german people that they have already ‘done their homework’ and are now reaping the fruits of their willingness to sacrifice their own personal wealth in order to keep the nations economy prosperous and competitive.

Sadly, there is no common understanding of the fact that this is utter nonsense and merely the result of a long-term campaign to further the interest of the shareholders of the financial and exporting industries on the backs of the domestic market and the majority of the german labour force.

So, while the chancellor and her cronies do everything in their power to prolong the crisis and destroy the idea of a european union as a community of nations, they are extremely successful in securing votes for the coming election in 2013.

Great article, and all that holds true for Australian federalism holds true in spades for Canadian federalism (even the relative decline of our manufacturing regions)

@talvez, I’d argue that it needs to get worse before it gets better. For example it seems desirable to liquidate/reorganize the legacy banks via some sort of nationalisation. Problem is things aren’t bad enough to make it politically acceptable and economically affordable (their market cap is too far above zero), so in this case it would actually help for things to get worse (as briefly as possible) before they can get better.

@nicolai, the silver lining of German public opinion ineptitude in this matter is that it’s easy to do things sideways without them noticing. Thanks God, that Jürgen Stark is not ECB president! 😉

@ Cig

“the silver lining of German public opinion ineptitude in this matter is that it’s easy to do things sideways without them noticing.”

You wouldn’t be talking about this, would you? 🙂

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a7ade85e-5184-11e1-a99d-00144feabdc0.html