The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Germany continues to kill the Eurozone

Earlier this week, the German statistical agency, De Statis released – Press release No.316 of 19 August 2024 – which confirmed that Germany continues to run policy settings that undermine the viability of the common currency. During the pandemic, Germany’s trade surplus declined significantly and the mainstream commentariat all pronounced that Germany had shifted direction and had finally learned that running an obsessive, export-led strategy that relied on suppression of domestic demand and increasing trade deficits elsewhere was fraught. Such a strategy had ensured the GFC was worse in Europe than elsewhere. The problem with that narrative is that it was wrong. The declining trade surpluses were driven by the temporary cost increases (mostly energy) that followed the pandemic and the price gouging by OPEC. The latest trade data shows that the economy has absorbed those shocks and is once again moving into large export surpluses that not only violate EU rules but also will further promote defensive strategies among its trading partners.

Earlier this week, the German statistical agency, De Statis released – Press release No.316 of 19 August 2024 – which confirmed that Germany continues to run policy settings that undermine the viability of the common currency.

The latest data released earlier this week (August 19, 2024) shows that:

German exports decreased by 1.6% to 801.7 billion euros year on year in the first half of 2024. Goods to the total value of 662.8 billion euros were imported to Germany in the first six months of 2024. This was a decrease of 6.2% compared with the first half of 2023. Germany’s foreign trade balance (exports minus imports) amounted to +138.8 billion euros in the first half of 2024, and was therefore 28.7% higher than in the first half of 2023 (+107.9 billion euros).

So even though export growth is down a bit, the suppression of domestic demand in Germany has seen a much larger decline in import expenditure and hence a widening of the trade surplus.

As I argue below, this means that far from seeking a finer balance between exports and imports, German authorities continue to follow an export-led growth strategy, which relies on external deficits of other nations.

Since the pandemic there has been an increase in protectionist thinking across the world and if nations do start pursuing more domestic strategies (for example, import replacement policies) then Germany is in jeopardy.

The first graph shows the evolution of German exports and imports since 1950 (in millions of euros) – Source Data.

The behaviour shifted in the early 1990s after the Maastricht Treaty began the process towards the common currency.

Throughout the 1990s, the German economy increasingly pursued aggressive export strategies, while at the same time suppressed domestic demand (Hartz reforms etc), which meant the trade surplus increased significantly.

Last month, the – Press release No.283 of 22 July 2024 – confirmed that “German exports to countries outside the European Union (third countries) were down 2.6%”, but the reality is that they have been flat for more than two years and are now in decline.

So much for the strategy to divert exports away from their depressed Eurozone partners towards the growth economies in the East.

Now that China is consolidating somewhat and digesting its real estate problems, Germany is stuck.

Its European partners cannot sustain the demand for German exports sufficient to sustain growth.

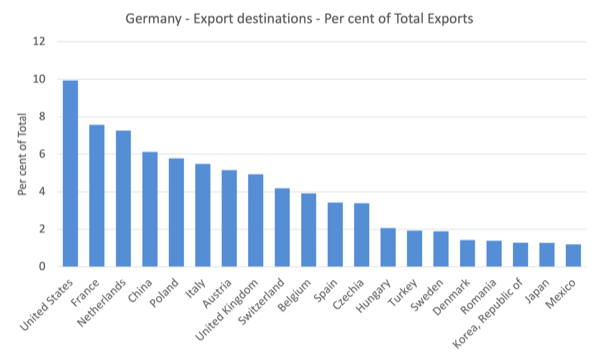

The following graph, which shows the top 20 destinations for German exports in 2023 in terms of the proportion of total exports, demonstrates Germany’s on-going reliance on intra-European trade markets for its exports.

In terms of its expenditure on imports, China is the top (11.5 per cent of total import spending), then Netherlands (7.7 per cent), the US (6.9 per cent), Poland (6 per cent), Italy (5.3 per cent), France (5.1 per cent), Czechia (4.5 per cent), Austria (4 per cent), Belgium (3.9 per cent) and Switzerland (3.8 per cent).

Last year (2023), Germany exports to its Eurozone neighbours totalled 1,590,063,399 thousand euros, while its imports from those neighbours only totalled 1,365,822,677 thousand euros – a massive trade surplus of 126,007,025 thousand euros.

So there is a leakage from German trade outside the Eurozone – that is, Germany doesn’t recycle the export revenue it receives from its Eurozone partners back into demand for Eurozone imports.

That is a deflationary situation and is what made the GFC much worse than it might have been for Europe.

The deliberate decision of the German government to suppress domestic demand, meant that the export surpluses had little opportunity for profitable returns by investing in the German economy.

As a result, German trade surpluses were recycled back into speculative real estate ventures in the other Eurozone nations in the lead up to the GFC, which created an oversized real estate boom (construction sector became abnormally large in some nations) that unfolded quickly when the US economy crashed on the back of the financial meltdown.

Within the EU governance framework, Germany is a serial offender and breaches the so-called – Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure – which decrees that no nation should run trade surpluses in excess of 6 per cent of GDP.

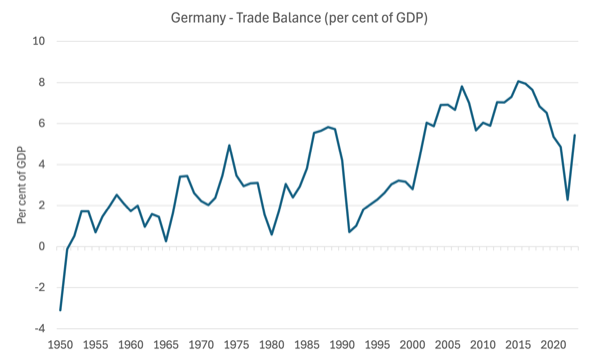

The following graph shows the trade balance as a percent of GDP since 1950.

The data is only strictly comparable post 1991.

Since 2000, Germany has been in violation of the MIP rules on current accounts in 16 of the 24 years.

And 4 of the years that it was within the MIP thresholds were during the pandemic period when import prices for energy rose significantly as a result of the supply constraints and OPEC+ price gouging.

The commentators, who initially claimed that the declining external surplus during the pandemic marked a new era for Germany where exports and imports would be more balanced, were wrong.

The decrease in the trade surplus was temporary and the overall policy bias in Germany remains to generate large export surpluses with suppression of domestic demand at the forefront of that strategy.

Private consumption expenditure growth is weak (wage suppression continues) and opportunities for profitable investment within Germany are reduced as a consequence.

The latest data suggests it is heading back into MIP default – the trade balance was 5.44 per cent in 2023.

Yet the European Commission turns a blind eye to it.

More worryingly is that the German export surplus obsession, in addition to undermining living standards for German citizens (by suppressing wages growth and domestic demand), endangers world stability.

By refusing to recycle the export revenue into import expenditure, Germany places pressure on the industrial bases of the nations it runs surpluses against.

Those nations then have a decision to make.

They can either become hostage to the German (and Chinese) manufacturing sectors, which leaves them vulnerable to the sorts of product quality and supply shortfalls that we saw during the pandemic, or they can seek to revitalise their own manufacturing sectors and reduce their reliance on exports.

We have already seen an increasing debate about self-reliance since the pandemic.

In May 2024, the Australian government, for example, has introduced its – Future Made in Australia – National Interest Framework – which provides:

Government support is needed to crowd-in the necessary private investment to scale up priority industries that will help the Australian economy navigate and prosper through these challenges …

(the) agenda fall into one of two streams:

- the Net Zero Transformation Stream, which includes industries where Australia will have a comparative advantage as the global economy transitions to net zero

- the Economic Resilience and Security Stream, which includes industries where some level of domestic capability is necessary to deliver economic resilience and security.

The Government will not admit that the Plan is protectionist but remember the – Duck test.

The point is that if those sorts of domestically-orientated approaches become more widespread and the World Trade Organisation starts to lose traction, then Germany is in deep trouble and will bring the rest of the Eurozone down with it.

In her 1936 book – Essays in the Theory of Employment (Basil Blackwell, Oxford) which was re-released in 1947, Joan Robinson sought “to apply the principles of Mr. Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money to a number of particular problems”.

In Part III, she provides an essay “Beggar-My-Neighbour Remedies for Unemployment” which is applicable to the current situation.

She wrote (p.156):

For any one country an increase in the balance of trade is equivalent to an increase in investment and normally leads (given the level of home investment) to an increase in employment … But an increase in employment brought about in this way is of a totally different nature from an increase due to home investment. For an increase in home investment brings about a net increase in employment for the world as a whole, while an increase in the balance of trade of one country at least leaves the level of employment for the world as a whole unaffected.

She then noted that:

In times of general unemployment a game of beggar-my-neighbour is played between nations, each one endeavouring to throw a larger share of the burden upon the others. As soon as one succeeds in increasing its trade balance at the expense of the rest, others retaliate, and the total volume of international trade sinks continuously, relative to the total volume of world activity.

She went on to outline the various policy devices that nations can use to precipitate a beggar-my-neighbour war including exchange rate depreciation, cutting wages, export subsidies and import restrictions (tariffs, quotas etc).

To some extent this is what Germany did after it entered the common currency.

The labour market deregulation (Hartz) and other policies shifted external competitiveness in favour of Germany at the expense of its Eurozone partners.

Germany sought to change its income distribution away from workers towards the export industries as a deliberate answer to the loss of exchange rate variability.

The strategy punished the trade deficit nations, who having lost the exchange rate capacity to adjust, were forced into harsh domestic austerity to cut wage costs etc as a result of the German export obsession.

If these nations start to deploy beggar-my-neighbour strategies – and why wouldn’t they – then there will be a major global recession as the nations adjust to the new reality.

Conclusion

It is clear that Germany hasn’t learned much from the past and the European Commission continues to ignore its breaches of the MIP rules.

That cannot end well.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Is there any evidence that a nation that has pursued an ‘export-led growth strategy’ can ever turn the ship around and pursue a more balanced strategy? Or does it become ‘addicted’ to such a strategy? Would it be fair to describe Germany, Japan, PRC, etc., as ‘addicted’ to their export-led growth strategies?

If the ideal is a public economy in surplus or at least balanced, I believe it’s by law in Germany and EU has it as its role model for its members. To balance the sectoral things, a trade surplus is necessary.

One has to remember that the majority of the imports in countries like Germany aren’t consumer goods and services for the people, the vast bulk of it is intermediate goods and services for the export industry. So often the export number is not the number of what is actually produced in Germany.

I was once in a internet argument with a rather famous blogger on this very subject. I claimed that it is possible to combine full emplyment with a trade deficit, while she said it was impossible. Seems to me that Joan Robinson did not disagree with mt stance. The reason for unemployment is that all countries pursue beggar myneighbour policy. If one country in this situation simply targeted full employment in its own country, I would actually expect this country to have a trade deficit. The country in question must of course have a floating currency. Otherwise I agree that full employment can’t be obtained, with the possible exeption in a short period.