I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

German trade surpluses demonstrate the failure of the Eurozone

The election of Donald Trump has stirred up the IMF and Germany, in particular. Trump’s trade advisor has claimed that Germany is manipulating the currency to maintain its competitiveness. A more general view is that the massive German external surplus is a reflection of a dysfunctional Eurozone, particularly the failed monetary policy stance of the ECB and the lack of a European-level (federal) fiscal policy capacity and willingness to expand domestic demand in the Member States. In fact, both views have credibility as I will explain. Last week (April 19, 2017), Eurostat released the latest trade data for the Eurozone – Euro area international trade in goods surplus €17.8 bn. It showed that Germany’s trade surplus continues to grow (it was 35.4 billion euros in January-February 2017, up 1.4 billion over the 12 months) in total. In 2016, Germany’s current account surplus was 8.6 per cent of GDP, which is obviously an outlier. What is required to redress this on-going dysfunction within the Eurozone would appear to be beyond the political mentality of the establishment polity in the Eurozone. And with Macron’s elevation to an almost certain Presidential victory in France, it is hard to see any dynamic for now emerging that will create change for the better. So as usual, the Eurozone muddles on – with a dysfunctional design architecture and an even more dysfunctional attitude to policy flexibility held by the powers to be. Germany is seriously responsible for a lot of this dysfunction.

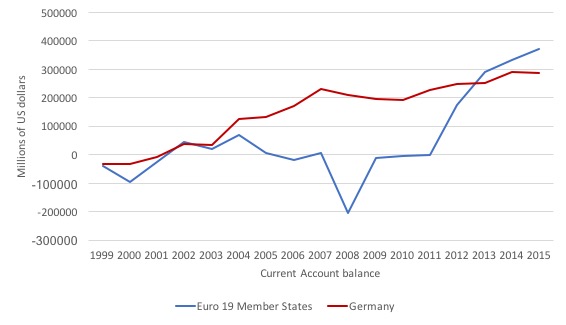

The following graph shows the current account of the Eurozone 19 Member States (in millions of Euros) since the inception of the currency union (January 1, 1999) and Germany (in US dollars – data is compiled by the OECD).

The pattern shown is indeed striking.

Up until 2011, the average annual current account surplus for the Eurozone was a small deficit ($US19,835 million). From 2012, the situation changed dramatically, with the average annual current account surplus for the Eurozone being $US293,079 million.

In 2015, Germany’s current account surplus was $US269,551 million around 91 per cent of the Eurozone’s total. Indeed throughout the history of the Eurozone, Germany’s trade position has dominated the Eurozone’s total as you would expect.

But the important point of the graph is that Germany’s position began to change in 2002 whereas the recent shift in the Eurozone external position begins around 2012 (late 2011).

That is why I cite two reasons for the overall shift in the Eurozone position.

First, the improvement in the early 2000s in Germany was down to its domestic policy (see below), whereas;

Second, the rise in Eurozone surpluses post 2012 has been significantly influenced by ECB policy and a failure to redress the glaring lack of federal fiscal capacity within the Eurozone.

The German responsibility

As background, you might like to read my blog – The European Commission turns a blind eye to record German external surpluses.

That blog discusses the failure of the European Union’s Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure, which was one of the “”new surveillance and enforcement mechanisms” that the Council introduced under the so-called “Six-Pack” to ‘bolster’ the Stability and Growth Pact.

I use ‘bolster’ to emphasise my view that the changes only made the SGP more unworkable than before.

At the time, the European Commission claimed these changes would force nations to submit “a clear roadmap and deadlines for implementing corrective action”.

The whole system was to be subjected to a huge surveillance operation (EU monitoring) with rigorous enforcement (fines equal to 0.1 per cent of GDP) and central intervention in a nation’s budgetary process.

The ‘Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure’ embedded in the Six-Pack uses ten “early warning” indicators that provide information about “macroeconomic imbalances and competitiveness losses”.

The upper warning threshold for an external surplus is 6 per cent of GDP.

What happens if a nation exports more than it imports (ignore, for simplicity, the income side of the current account)?

The net outflow of real goods and services would be accompanied by accumulating financial claims against the rest of the world.

This is because the demand for the nation’s currency to meet the payments necessary for the exports would exceed the supply of the currency to the foreign exchange market to facilitate the import expenditure.

How might this imbalance be resolved? There are a number of ways possible.

A most obvious solution would be for foreigners to borrow funds from the domestic residents. This would lead to a net accumulation of foreign claims (assets) held by residents in the surplus nation.

Another solution would be for non-residents to draw down local bank balances, which means that net liabilities to non-residents would decline.

Thus a nation running a current account surplus will be recording net private capital outflows and/or the central bank will be accumulating international reserves (foreign currency holdings) if it has been selling the nation’s currency to stabilise its exchange rate in the face of the surplus.

Current account deficit nations will record foreign capital inflows (for example, loans from surplus nations) and/or their central banks will be losing foreign reserves.

Large current account disparities emerged between nations in the 1980s as capital flows were deregulated and many currencies floated after the Bretton Woods system collapsed.

European nations such as Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland were typically recording large and persistent current account surpluses and with a significant proportion of their trade being with other European nations, the imbalances grew within Europe as well as between Europe and elsewhere.

Think about the sectoral balances arithmetic. If a Member State achieve a balanced fiscal outcome and is sitting on the current account surplus threshold (6 per cent), then its private domestic sector will be saving overall 6 per cent of GDP.

Where will those savings go?

I have discussed how Germany maintained its external competitiveness once it could no longer manipulate the exchange rate in previous blogs.

Please read my blogs – Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home and Germany should look at itself in the mirror – for more discussion on this point.

The savings may go into the domestic economy if there are profitable opportunities to invest. But in Germany’s case, its whole strategy was based on suppressing domestic demand (Hartz reforms, wage suppression, mini-jobs etc), and so profitable investment opportunities were limited in the German economy.

As a result and capital sought profits elsewhere.

The persistently large external surpluses which began long before the crisis (and 6 per cent is large) were the reason that so much debt was incurred in Spain and elsewhere. German investors pushed capital externally.

Germany is clearly supplying large flows of capital to the rest of the world.

At 8.6 per cent, the outflow of capital is ridiculous. Such surpluses rely on offsetting external deficits elsewhere – for example, the US, which explains why that nation is focusing on Germany at present as it increases its protectionist narrative.

To resolve this problem (which is a massive imbalance between domestic saving and investment), Germany requires higher domestic demand and faster wages growth both to boost the very modest consumption performance and to attract investment into the domestic market.

It also could stimulate public spending – say, to start the long process of restoring quality to its public infrastructure which has been seriously degraded by the austerity mentality of successive German governments.

But such a change would be at odds with the mercantile mindset that dominates the nation because it would reduce the competitive advantage that Germany enjoys over other nations that have treated their workers more equitably.

And, the European Commission has not acted to stop Germany gaming the system even further.

So from one perspective there is massive scope for the German government to expand its net spending (reduce its surplus) to stimulate domestic spending and import spending, which would reduce the massive and unsustainable external surplus.

Which, in part, would help Greece and other beleaguered Member States in the Eurozone.

The Eurozone responsibility

While Germany was clearly gaming its Eurozone partners with its own version of ‘internal devaluation’ (Hartz etc), more recently, it is clear that ECB monetary policy settings are implicated in the suppressed value of the euro.

The easing of monetary policy in the Eurozone to deal with the GFC helped the slide in the euro as investment funds placed their cash elsewhere.

The uncertainty about the continued viability of the common currency and the parlous economic performance also did not help.

The following graph shows the movement in the Euro/USD trade-weighted parity since the inception of the Eurozone in January 1, 1999.

Going into the crisis the peak euro-US dollar parity in trade-weighted terms came on July 15, 2008 when it took USD1.599 to buy one euro. It fell to $US0.8252 by July 20, 2015, a 48.4 per cent decline.

Between the July 15, 2008 peak and June 8, 2010, the trade-weighted euro fell by 25.3 per cent.

It was no surprise that as the world trade patterns adjusted to that reality, the current account position of the Eurozone in general began to change – from deficit to surplus.

This transition was also aided by the appallingly low growth and continued recession within many Eurozone Member States, which saw external balances move to surplus as a result of a deep suppression of import expenditure.

Also, there was not so much as an export boom but a suppression of imports due to elevated levels of unemployment and widespread national income losses.

As the graph at the outset shows, the Eurozone current account surplus skyrocketed mostly due to Germany and a lesser extent, the Netherlands.

Out of the $US350 billion surplus in 2016, only $US20 billion was contributed by the other 17 Eurozone Member States, a staggering imbalance in itself.

And a closer look at the most recent data tells us that while German exports rose by 7 per cent since the beginning of 2016 the Intra-EU growth was just 5 per cent, while the Extra-EU growth was 10 per cent.

Similarly, in terms of the overall trade balance, Germany’s Intra-EU surplus was 12.4 billion euros in February 2016 and this fell to 11.4 billion euros by February 2017.

Its Extra-EU surplus rose from 21.6 billion euros in February 2016 to 24 billion euros a year later.

Taken together the overall surplus rose from 34 to 35.4 billion euros in the last 12 months.

So the German position is improving as a result of trade external to the European Union and that reinforces the claim that the suppressed exchange rate is at work.

While most of the attention in the Eurozone since the GFC broke has been on the disasters in the weaker Member States, not aided by Germany’s position pre and post-crisis, Germany, itself, is now caught in a domestic disaster that it created through its policies from the early days of the monetary union.

The birds are coming home to roost!

Its own domestic property market is inflating quickly because of the low Eurozone wide interest rates. Further, its ridiculously large current account surpluses require domestic stimulus – via stronger wages growth and fiscal expansion.

The fiscal expansion is required not in the least to fix up the decaying public infrastructure that has resulted from years of pursuing fiscal surpluses.

But with the export boom feeding national income growth and domestic inflation (via housing) pushing up, such a stimulus might push inflation up further.

They are now caught betwixt, in other words.

Their response, however, has to be to use fiscal policy to increase domestic demand but redistribute domestic spending away from housing.

The political mentality of the German elites, is however, not disposed to that sort of response and so the problem will continue.

And if yesterday’s French election results are any guide, there will not be any significant pressure from that nation on Germany to respond.

There is a desperate need for a federal fiscal capacity in the Eurozone to override these national failures to adjust fiscal policy in the interests of the whole.

Conclusion

The results of the first round of the French Presidential election are now in and it is fairly obvious that: (a) the major political parties have been rejected by the French voters; and (b) that the non-National Front voters will probably band together and elect Emmanuel Macron as the next President.

Even though he touts himself as a ‘new’ centrist voice in French politics, he is avowedly pro-Eurozone and a neo-liberal when it comes to economic policy.

What these means for our discussion today, is that there will be minimal political forces to alter the current state of affairs in the Eurozone.

What is required is a massive rebalancing of domestic demand (savings and investment including public spending) and that is not about to happen under current Eurozone policy positions.

So don’t expect a resolution of this issue soon and when the next crisis hits the damage will be worse than the last time, given that the Eurozone has barely got back on its feet and some nations (Greece etc) are in a tragic position 9 years on.

And the political grasp on power that the pro-European narrative seems to maintain at present (if the French election results are anything to go by) will diminish and the signicant percentage of the vote that Le Pen received yesterday will expand.

The rejection of the main parties in France is symptomatic of a growing resentment to this dysfunctional policy regime imposed by Brussels and Frankfurt, aided by the bullying IMF.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Can someone explain why the IMF pokes its nose into the EU at all? The EU is a wealthy area. It does not need help from any international organization. The EZ is monetarily sovereign: it can create any amount of money at the press of computer keyboard buttons if it chose to. And if it chose to, it could perfectly well halve the austerity endured by Greece.

ISTM that Germany is following Japan down the exporter with excess savings route – but in a fixed exchange rate lock with a load of other states.

I’m not sure anybody has the correct handle on the aggregation function in international trade and capital flows. It certainly isn’t just a simple summation.

If Hamon and Mélenchon had combined the left vote would have been ~26%.

People understood and wanted the progressive left agenda too. People are fed up with neoliberalism here especially the youth.

Macron is from the same school of thought as conventional austerity economics like disgraced Jean Triole. Fine with insider trading, obscene CEO powers, large manifestations of power and wealth for the elites, want to continue with the current charade of losers (southern Eurozone members).

Best case scenario under Macron is that France undergoes tepid growth enough to appease the electorate which will be supported by the EU but only for political means. Will still see no change to chômage or anything meaningful. As per usual every January when people try to enter the workforce the unemployment participation rate will surge and Macron will say he cant do anything about it other than supply-side economics.

German poverty in 2017:

http://www.der-paritaetische.de/presse/news/armutsbericht-2017-anstieg-der-armut-in-deutschland-auf-neuen-hoechststand-verbaende-beklagen-skanda/

‘it can create any amount of money at the press of computer keyboard buttons if it chose to. ‘

Ralph, isn’t the answer straighforward? Preservation of vested interests in the form of maintaining asset bubbles and inequality and so that wealth extraction can continue.

Also; so that Lagarde can swan around the world being wined and dined and continue the lifestyle she is accustomed to. (smiley emoticon).

Germans have been more than willing to endure haartz reforms based on their reports of satisfaction with government policy and general stability of the incumbent political parties.

I think this may have something to do witht he historically low and stable housing costs.One can better live with low wages if rent is cheap and secure.

If they are beginging to develop higher property prices and anglo style property markets I would think that things will get more volatile politcally.

Also I am not so sure a macron victory is in the bag,just yet,I have come across oem reports of melonchntron voters saying that they will vote for marine le pen

Hi Bill.

“The savings may go into the domestic economy if there are profitable opportunities to invest.”

I assume you are using the term “invest” here in a lose sense? Like traxpayer’s money?

France had a huge trade deficit last year, over 50b euros, noone point out that almost 100% of it is with Germany!!!!

Bill, you wrote, “The easing of monetary policy in the Eurozone to deal with the GFC helped the slide in the euro as investment funds placed their cash elsewhere.”

I saw on youtube a claim that people moved out of euros because of the money grab in Cyprus. The ECB or someone like them needed euros to prop up something and they just took a percentage out of every bank account in a Cypriot bank.

This spooked the investors. If the EU could do it once they could do it again.