Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australia – lowest nominal wages growth on record leading to significant real wage cuts

It’s Wednesday and I usually don’t write much on my blog. But today, history was made and so I thought I should at least cover it. Today (November 18, 2020), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest- Wage Price Index, Australia – (September-quarter 2020). The ABS reported that while “the September quarter is generally a quarter of solid wage growth … the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a subdued rate of wage growth in the September quarter 2020”. However, they might also have said that today’s result was “the lowest quarterly growth in the 22-year history of the WPI”. Private sector grow was just 0.1 per cent and public sector growth was just 0.2 per cent. The overall WPI growth was just 0.1 per cent. With the quarterly inflation in the September-quarter was recorded at 0.693 per cent, real wages thus fell for Australian workers. Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.

The summary results (seasonally adjusted) for the September-quarter 2020 were:

- The Wage Price Index grew by 0.1 per cent in the September-quarter 2020 – the lowest on record, and 1.4 per cent over the previous 12 months – slowing.

- The growth for the private sector was 0.1 per cent in the September-quarter and 1.2 per cent over the year – slowing.

- The growth for the public sector was 0.2 per cent in the September-quarter and 1.8 per cent over the year – slowing.

Nominal wage and real wage trends in Australia

The ABS Media Release – said that:

The September quarter is generally a quarter of solid wage growth, however, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a subdued rate of wage growth in September quarter 2020 …

Organisations continued to adjust to the economic uncertainty, recording fewer end of financial year wage reviews and delaying enterprise bargaining agreement increases. This led to a significantly reduced number of jobs recording wage rises when compared to previous September quarters …

… wages rose 0.4% in September quarter 2020. Private sector wages rose 0.5%, and the public sector rose 0.4%. Contributions to the growth in private sector wages came mostly from full or partial restoration of wages following wage reductions in June quarter 2020.

The inflation measures, which the Reserve Bank of Australia uses when assessing underlying movements, for the September-quarter were:

1. Basic CPI measure: 0.693 per cent

2. Core inflation excluding volatile items: 0.9 per cent per annum.

2. Weighted median: 0.3 per cent.

3. Trimmed mean: 0.4 per cent.

Which means that irrespective of the inflation measure used, real wages were cut in the September-quarter for both public and private employees.

The wage series used in this blog post is the quarterly ABS Wage Price Index. The Non-farm GDP per hour is derived from the quarterly National Accounts.

Productivity data available via the RBA Table H2 Labour Costs and Productivity.

The ABS Information Note: Gross Domestic Product Per Hour Worked – says that:

In Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (cat. no. 5206.0) and Australian System of National Accounts (cat. no. 5204.0) the term ‘GDP per hour worked’ (and similar terminology for the industry statistics) is generally used in preference to ‘labour productivity’ because:

– the term is more self-explanatory; and

– the measure does not attribute change in GDP to specific factors of production.

On price inflation measures, please read my blog – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

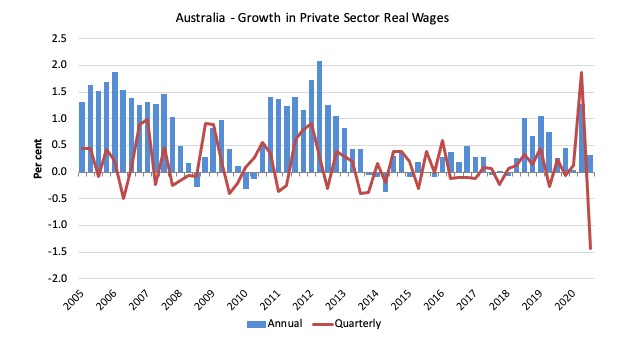

The first graph shows the growth in private sector real wages since the September-quarter 2005 to the September-quarter 2020. The Core inflation measure excluding volatile items is used.

The blue bars are the annual rate of change, while the red line is the quarterly rate of change.

The September-quarter result is an outlier – given the temporary government decision to offer free child care (now rescinded).

Throughout 2017 and into 2018, real wages growth was negative. But then there were several quarters of modest real wages growth. The trend, however, is towards zero real wages growth.

The latest quarter shows a dramatic decline in real wages.

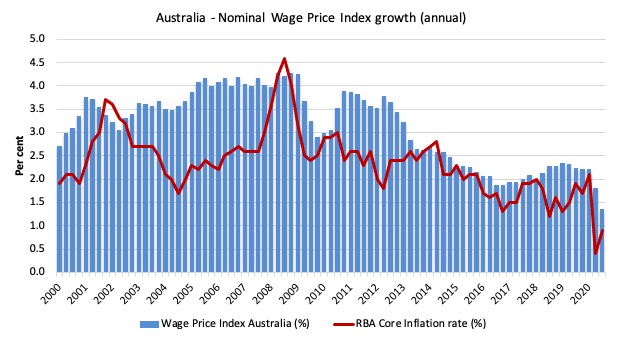

The next graph shows the overall annual growth in the Wage Price Index (public and private) since the December-quarter 2000 (the series was first published in the December-quarter 1997).

I also superimposed the RBA’s core annual inflation rate (red line). The blue bar area above the red line indicate real wages growth and below the opposite.

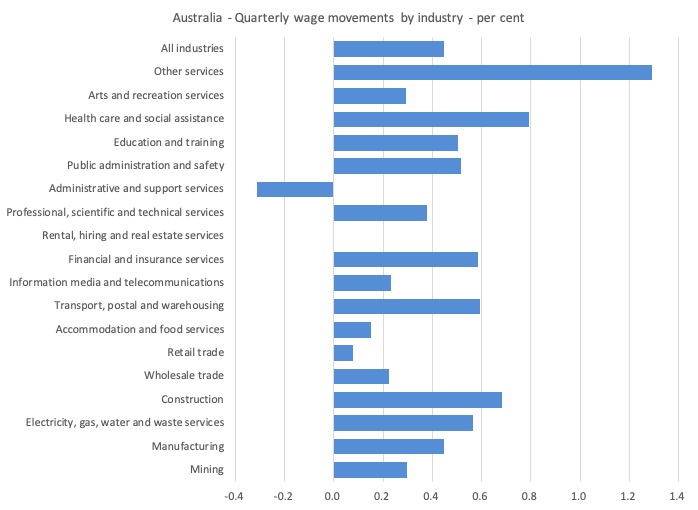

Sectoral Variability

The aggregate data shown above hides quite a significant disparity in quarterly wage movements at the sectoral level, which are depicted in the next graph.

The ABS also reported that:

Annual wage growth to the September quarter 2020 ranged from 0.5 per cent for the Accommodation and food services and Administrative and support services industries to 2.4 per cent for the Financial and insurance services and Education and training industries.

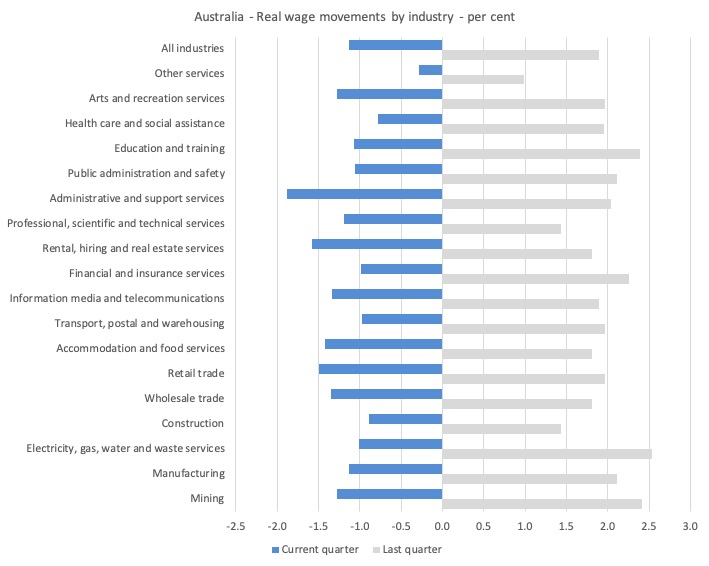

While nominal wages growth was mostly positive, albeit modest, the next graph shows the movements in real wages and you can see that workers in all occupational groups lost purchasing power in the September-quarter.

Workers not sharing in productivity growth

Real wages growth means that the rate of growth in nominal wages is outstripping the inflation rate, another relationship that is important is the relative growth of real wages and productivity.

Historically (for periods which data is available), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards.

In effect, productivity growth provides the ‘space’ for nominal wages to growth without promoting cost-push inflationary pressures.

There is also an equity construct that is important – if real wages are keeping pace with productivity growth then the share of wages in national income remains constant.

Further, higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth then spawned new activity and jobs, which absorbed the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

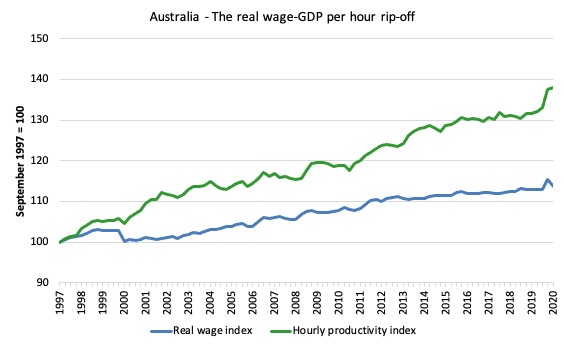

Taking a longer view, the following graph shows the total hourly rates of pay in the private sector in real terms (deflated with the CPI) (blue line) from the inception of the Wage Price Index (December-quarter 1997) and the real GDP per hour worked (from the national accounts) (green line) to the September-quarter 2020.

It doesn’t make much difference which deflator is used to adjust the nominal hourly WPI series. Nor does it matter much if we used the national accounts measure of wages.

But, over the time shown, the real hourly wage index has grown by 13.6 per cent, while the hourly productivity index has grown by 38 per cent.

So not only did real wages decline in the September-quarter, the growth in productivity widened the gap between the two series even further.

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the gap would be much greater. Data discontinuities however prevent a concise graph of this type being provided at this stage.

For more analysis of why the gap represents a shift in national income shares and why it matters, please read the blog post – Australia – stagnant wages growth continues (August 17, 2016).

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Mostly to profits.

One might then claim that investment will be stimulated.

At the onset of the GFC (September-quarter 2008), the peak Investment ratio (percentage of private investment in productive capital to GDP) was 23.3 per cent.

It peaked at 24.3 per cent in the September-quarter 2013. But in recent quarters it has steadily fallen and in the June-quarter 2020 (most recent data) it stood at 17.9 per cent.

Some of the redistributed national income has gone into paying the massive and obscene executive salaries that we occasionally get wind of.

Some will be retained by firms and invested in financial markets fuelling the speculative bubbles around the world.

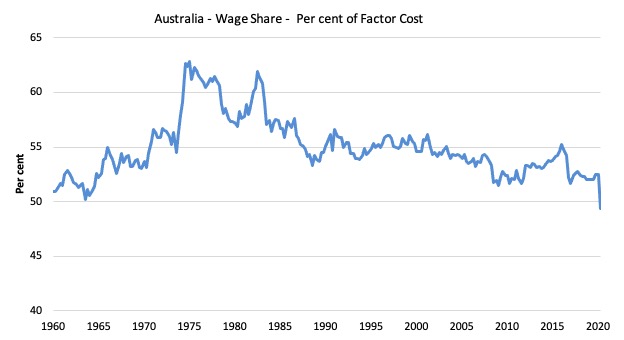

Now, if you think the analysis is skewed because I used GDP per hour worked (a very clean measure from the national accounts), which is not exactly the same measure as labour productivity, then consider the next graph.

It shows the movements in the wage share in GDP (at factor cost) since the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2020.

The only way that the wage share can fall like this, systematically, over time, is if there has been a redistribution of national income away from labour.

I considered these questions in a more detailed way in this blog post series:

1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 1 (November 20, 2019).

2. 1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 2 (November 21, 2019).

And the only way that can occur is if the growth in real wages is lower than the growth in labour productivity.

That has clearly been the case since the late 1980s. In the March-quarter 1991, the wage share was 56.6 per cent and the profit share was 22.2 per cent.

By the June-quarter 2020, the wage share had fallen to 49.4 per cent and the profit share risen to 31.1 per cent.

A massive redistribution of income towards profits has occurred.

The relationship between real wages and productivity growth also has bearing on the balance sheets of households.

One of the salient features of the neo-liberal era has been the on-going redistribution of national income to profits away from wages. This feature is present in many nations.

The suppression of real wages growth has been a deliberate strategy of business firms, exploiting the entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment over the last two or three decades.

The aspirations of capital have been aided and abetted by a sequence of ‘pro-business’ governments who have introduced harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce the trade unions’ ability to achieve wage gains for their members. The casualisation of the labour market has also contributed to the suppression.

The so-called ‘free trade’ agreements have also contributed to this trend.

I consider the implications of that dynamic in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009).

As you will see, I argue that without fundamental change in the way governments approach wage determination, the world economies will remain prone to crises.

In summary, the substantial redistribution of national income towards capital over the last 30 years has undermined the capacity of households to maintain consumption growth without recourse to debt.

One of the reasons that household debt levels are now at record levels is that real wages have lagged behind productivity growth and households have resorted to increased credit to maintain their consumption levels, a trend exacerbated by the financial deregulation and lax oversight of the financial sector.

Real wages growth and employment

The standard mainstream argument is that unemployment is a result of excessive real wages and moderating real wages should drive stronger employment growth.

As Keynes and many others have shown – wages have two aspects:

First, they add to unit costs, although by how much is moot, given that there is strong evidence that higher wages motivate higher productivity, which offsets the impact of the wage rises on unit costs.

Second, they add to income and consumption expenditure is directly related to the income that workers receive.

So it is not obvious that higher real wages undermine total spending in the economy. Employment growth is a direct function of spending and cutting real wages will only increase employment if you can argue (and show) that it increases spending and reduces the desire to save.

There is no evidence to suggest that would be the case.

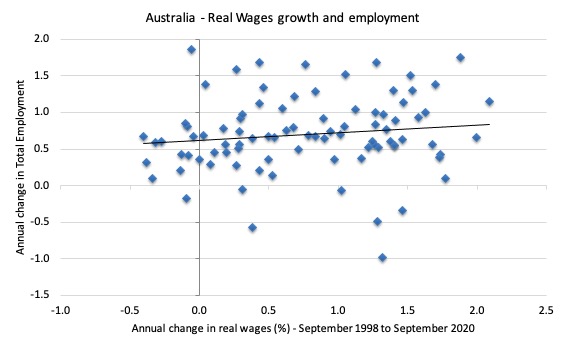

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages (horizontal axis) and the quarterly change in total employment (vertical axis). The period is from the December-quarter 1998 to the September-quarter 2020. The solid line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: When real wages grow faster so does employment although from a two-dimensional graph causality is impossible to determine.

However, there is strong evidence that both employment growth and real wages growth respond positively to total spending growth and increasing economic activity. That evidence supports the positive relationship between real wages growth and employment growth.

Noting that we should not draw causality from two-dimensional cross plots.

Conclusion

In the September-quarter 2020, Australia recorded its lowest rate of wages growth on record (in terms of the Wage Price Index – available since the September-quarter 1997).

Nominal wages increased by just 0.1 per cent.

But, given the quarterly inflation in the September-quarter recorded 0.693 per cent, real wages thus fell for Australian workers.

Further, over the longer period, real wages growth is still running well behind the growth in GDP per hour (productivity), which has allowed profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.

Bleak economic times.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill, I’m an American, so maybe this use if the word “cuts” is an Aust. thing.

Here ‘cuts’ implies a deliberate action to cut something.

If you don’t want to imply that, the say “drop (or reduction in, etc.) in real wages”.

Delete this if you want to.

@Steve_American It is reasonable to think, especially after reading this blog, that Governments have an alternative to their policy that has as an objective (another reasonable presumption) for ‘profits to secure a substantially increased share of national income.’ Their action is deliberate and that objective is being achieved.

Greenpeace USA has just released a “Just Transition Agenda” that is stunning in its breadth, depth, optimism, and courage. Among the measures called for is “the creation of a National Investment Authority, to mobilize public investments to build the future we want, and a National Employment Authority, to put people to work with guaranteed, dignified, family-sustaining jobs in the new economy.” I encourage Bill’s readers to read through the Greenpeace agenda (easily found via web search) and to take heart that, among many other worthy policy recommendations, Greenpeace USA has apparently thrown its support behind a JG or something very much like it.

“Just Transition Agenda”? There a a bunch of them.

Greenpeace has published a “Just Recovery Agenda”. I’m having a look at that.

Having read/skimmed the Just Transition Agenda, I think it looks not bad. It’s disappointing to start, in that it seems to be just going around and around. I think the “Changing the Story” section repeats the previous “Values for a Just Recovery”, and that will be recapitulated in the “A Policy Agenda for a Just Recovery” which follows. It picks up after that with specific references to actions and existing proposed legislation to make those policies happen. Looking into those will tell us the real value of the program.

There’s no particular call on MMT principles; they propose setting iup specific Funds to accomplish specific goals, and we would advise them, if they asked, that simply approving the expenditure along with the program of action is by far the smoothest way to do things. Probably also advise them that the right to dignified work that they encourage can be provided in a large part by the Job Guarantee that Mitchell, Tcherneva, and the others have laid out.

Here’s more language from the Greenpeace USA “Just Transition Agenda” that would seem in sync with MMT’s JG proposal: “dignified work…must be guaranteed; …everyone has what they need to thrive, including dignified work; …ensure the right to dignified work; …securing the right to family-sustaining, dignified jobs….” As for the source of securing (and funding) this RIGHT to dignified work (among others): “It’s time to put our elected officials to work for the people, and to use the tools and power of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT to solve problems rather than exacerbate them” (caps mine). Granted, there’s no explicit reference in the Greenpeace agenda to MMT or to its JG proposal, nor to the scope of currency-sovereign federal agency constrained only by available resources. Nevertheless, as the old saying goes about the duck, if it looks like one, walks like one, talks like one, swims like one, well….