The US is now a rogue state. One example is the conduct of the US…

ABCD, social capital and all the rest of the neoliberal narratives to undermine progress

I was in a meeting the other day and one of the attendees announced that they were sick of government and were looking at other solutions such as social capital and community empowerment to solve the deep problems of welfare dependency that they were concerned about. The person said that all the bureaucrats had done was to force citizens onto welfare with no way out. It had just made them passive and undermined their free will. It was a meeting of progressive people. I shuddered. This is one of those narratives that signal surrender. That put up the white flag in the face of the advancing neoliberal army intent on destroying everything in its way. The ultimate surrender – individualise and privatise national problems of poverty, inequality, exclusion, unemployment – and propose solutions that empower the individuals trapped in ‘le marasme économique’ created by states imbued with neoliberal ideology. The point is that the Asset-Based-Community-Development (ABCD) mob, the social capital gang, the new regionalists, the social entrepreneurs are just reinforcing the approach that creates the problems they claim they are concerned about. The point is that it is not the ‘state’ that is at fault but the ideologues that have taken command of the state machinery and reconfigured it to serve their own agenda, which just happen to run counter to what produces general well-being. That is why I shuddered and took a deep breath.

Quite a different map

For the period after the US election, the world had to endure the US map coloured red and blue (the colours of my AFL football team by the way) with all sorts of speculation which way the colours would fall.

This is the map the GOP wanted. Or rather, the map they created.

It was provided by – Covid Exit Strategy – which is a group of public health professionals.

It tracks the COVID-19 spread across America. Very scary.

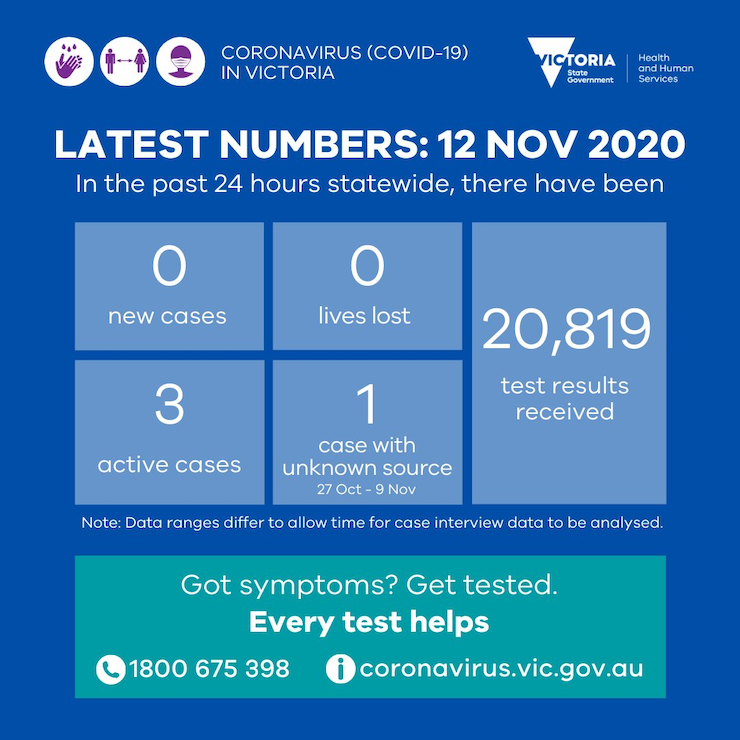

Compare it to this graphic from the Department of Health and Human Services this morning telling us that this was the 13th day of zero cases and zero deaths in Victoria and that there are only 3 people left in Victoria who are sick with the virus.

Nationwide there were only 8 new cases yesterday, almost all of them returned travellers who are in quarantine.

Various Third Way myths to hide neoliberal intent

As background reading:

1. Social entrepreneurship … another neo-liberal denial (November 11, 2009).

2. Social inclusion principles – another failed vision (May 27, 2009).

3. StartUp Loans – neo-liberal smokescreen which denies macroeconomic reality (May 29, 2012).

4. The Big Society aka BS (January 3, 2011).

5. The blight of the visitor economy (February 6, 2018).

6. The best way to eradicate poverty is to create jobs (November 21, 2011).

7. The (neo-liberal) Third Way infestation continues (January 18, 2017).

8. Urgent need for governments to deal with urban decay and green up our cities (June 9, 2020).

9. Brainbelts – only a part of a progressive future (July 25, 2016).

10. The urban impact of the failure of austerity (January 26, 2016).

What I am writing about today considers issues that were raised in the background reading.

Everyone wants to think they are important and would like to think they have something to offer. They want recognition. That is a reasonable aspiration.

Most want to live in nice communities that are vibrant, safe, interesting and present opportunities. Again a reasonable aspiration.

But neoliberalism exploits those reasonable aspirations and uses them as cover to further hollow out the state, while demonising the state for creating our problems.

We learn to loathe bureaucrats and ignore they are just workers acting under instruction.

We learn to vilify welfare recipients as lazy people who just want to take handouts while the rest of us work hard.

We learn the language that neoliberals provide us with to impugn those left behind – dole bludgers, welfare cruisers, etc.

The language reinforces the narrative that they are struggling because they are defective human beings who just want an easy ride.

I have always wondered what ride that is when the government forces the unemployed in Australia to live below the accepted poverty line in poor housing with not much discretionary income to spend on ‘living it up’. But still we ignore reality – the narrative rules.

We also learn the language they provide to congratulate those who are playing ball – social capital, community engagement, asset-based community development (ABCD), social entrepreneurship, the Big Society and all the rest of it.

We are told this is a new way of thinking – a Third Way – between the worn out ideologies of free markets and socialism, as if those extremes ever existed anyway.

Social democratic parties rush headlong into the Third Way narrative thinking they are onto something refreshing and empowering.

They think communities can empower themselves out of poverty, out of passive welfare, out of unemployment – by using the capacities that exist in those communities.

Evangelistic-style gurus to world tours preaching community empowerment and asset registers and building social capital. They typically make heaps as consultants.

The problem with all this is that the conservatives are laughing at the diversion they have created.

What better way to hide what is really going on than getting all these bleeding heart progressives out there with an abundance of energy as front-line troops pushing your own agenda.

Genius.

A 2014 article published in the Journal of Community Practice – Neoliberalism With a Community Face? A Critical Analysis of Asset-Based Community Development in Scotland – by Mary Ann MacLeod and Akwugo Emejulu (behind paywall) – is worth reading if you want to learn more.

The article builds on the excellent 2015 book by Akwugo Emejulu – Community development as micropolitics: Comparing theories, policies and politics in America and Britain (Bristol, Policy Press).

This is an account of what happened in history. It is real.

It is the same sort of approach that Thomas Fazi and I took in our 2017 book – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, September 2017) – where we concentrated on locating the turning points in progressive thinking and politics that opened the door and nurtured the rise of neoliberalism.

Akwugo Emejulu is an academic sociology professor at Warwick.

In her 2015 book, we learn that there were three “politically salient historical moments” (p.8) in the two decades after 1967 that marked the change in thinking in community development.

1. When the Left splintered in the decade period of turmoil after 1968.

2. The emergence of the neoliberal Right in the late 1970s.

3. And the period in the 1990s, where the politics of the Left and the Right converged such that we were splitting hairs trying to distinguish between the two previously disparate approaches.

By the time the GFC came along, the social democratic political forces were mouthing Third Way speak in everything they said.

And when the conservatives took back control all the work was really done for them.

The public spending cutbacks in the 1980s and on, the reduction in real income support for the unemployed who had been rendered in that state by the surplus obsessions that governments adopted, the cuts to dental and health care for the poor, the cuts to legal aid, the cuts to public school funding, the privatisation of energy, transport, health care, banking, water and the rest of the essential services – all undermined well-being.

But at the same time that neoliberals were pursuing these policies that they knew would damage the fabric of society and pit people against each other, they spawned new movements.

These movements claimed that (from the article cited above, p.431):

As the state withdraws from different aspects of public life, the government argues that individuals, families, and community groups will be able to fill this vacuum through their local knowledge, assets, and energy to rebuild local services on their own terms and in ways that meet their interests and needs.

And in marched so-called ABCD that had all the policy makers falling over each other to pay consultants to produce fancy (expensive) PowerPoint slide shows with all sorts of ritzy diagrams and arrows going everywhere extolling the virtues of social capital and building assets in communities.

The individual was promoted as all powerful.

Forget that nasty state. Who wants the state in our ‘bedrooms’. We can do this.

ABCD was an attack on needs-based community policy (p.431):

By asset-based community development (ABCD), we mean the movement within the field of community development that seeks to reorient theory and practice from community needs, deficits, and problems to a focus on community skills, strengths, and power

The authors note that (p.431):

ABCD is a response and a capitulation to the rise of neoliberalism and its values of individualization, marketization, and privatization of public life.

The modern variant of this is the fervour among progressives for Basic Income Guarantees.

Another capitulation to neoliberalism and the cult of the indvidual. It is all clothed in community (collectives) but it the anathema of that.

The authors note that:

Rather than seeing ABCD as a radical departure from politics as usual, we argue that ABCD is an iteration of an on-going American project to advance a politics that is antielitist, antiinstitutional and, consequently, highly individualized and hyper-local. Authenticity is crucial in populist politics and this can only be secured through a practice of us versus them – in the case of ABCD, the us are communities and the them are elite state actors

A sort of earlier rendition of ‘drain the swamp’. Trumpian politics is just an extension of this sort of anti-state reasoning, which uses the state’s capacity to enrich the movement.

The argument supporting ABCD was that urban communities were being decimated – crime rates rising, community participation was falling and so there was a need to forget about “social welfare service access and delivery” and, instead, focus on “the role, purpose, and function of the services themselves and local people’s relationship to these services”.

But what is not emphasised is the macroeconomic constraints that have created these urban hell holes, the hollowed out regions, the decaying industrial towns, the disadvantaged indigenous communities.

As governments started to pursue ‘small’ government and impose fiscal austerity on their nations, who would have guessed, regions and towns started to fall behind.

One of the first things a student should learn about in economics is the concept of a macroeconomic constraint. No matter how hard a unemployed people try to get work, if there are not enough jobs on offer then some will always miss out.

I use the – 100 dogs and 94 bones parable – to make that point, although the 94 is a moving number depending on the state of the economy.

Imagine a small community comprising 100 dogs. Each morning they set off into the field to dig for bones. If there enough bones for all buried in the field then all the dogs would succeed in their search no matter how fast or dexterous they were.

Now imagine that one day the 100 dogs set off for the field as usual but this time they find there are only 94 bones buried.

Some dogs who were always very sharp dig up two bones as usual and others dig up the usual one bone. But, as a matter of accounting, at least 6 dogs will return homebone-less.

Now imagine that the government decides that this is unsustainable and decides that it is the skills and motivation of the bone-less dogs that is the problem. They are not “boneable” enough.

They need social capital and community empowerment. Consultants are hired to do ABCD assessments.

A range of dog psychologists and dog-trainers are called into to work on the attitudes and skills of the bone-less dogs. The dogs undergo assessment and are assigned case managers. They are told that unless they train they will miss out on their nightly bowl of food that the government provides to them while bone-less. They feel despondent.

Anyway, after running and digging skills are imparted to the bone-less dogs things start to change. Each day as the 100 dogs go in search of 94 bones, we start to observe different dogs coming back bone-less. The bone-less queue seems to become shuffled by the training programs.

However, on any particular day, there are still 100 dogs running into the field and only 94 bones are buried there!

The main reason that the supply-side approach is flawed is because it fails to recognise that unemployment arises when there are not enough jobs created to match the preferences of the willing labour supply. The research evidence is clear – churning people through training programs divorced from the context of the paid-work environment is a waste of time and resources and demoralises the victims of the process – the unemployed.

Akwugu Emejulu writes:

A key target of ABCD is the welfare state which is constructed as bureaucratic, hierarchical and anti-democratic because, ABCD supporters argue, it breeds a culture of dependency in poor communities. In contrast, ABCD is presented as an inclusive and democratic process of empowering citizens by ‘ignoring the empty half of the glass’ of poverty and inequality.

Individuals are assets – local assets. They are not “problems to be fixed by the state” even when it is obvious the ‘state’ creates the problem through the use of dysfunctional policies, that reflect an ideology that doesn’t value the individuals anyway.

She traces the beginnings of ABCD to “the rolling back of the social welfare state in 1980s America.”

This was the Reagan years and he set about destroying the “Great Society Reforms” on LBJ in the 1960s.

It was clear that:

The Reagan Administration not only eliminated, reduced and/or privatised a range of public services but also actively targeted for de-funding and closure community organisations that supported conflict models of social action.

ABCD was not a movement designed to fix the community deficits that the neoliberal macro constraints had created but rather:

… to displace and neutralise radical community organising and development.

Social welfare professionals were being pushed into becoming front-line neoliberal troops under the guise of ABCD saviours.

The ABCD proponents (and the Basic Income gang) all talk about grassroots empowerment. A process to unleash massive creative potential suppressed by passive welfare and state bureaucracies.

But in reality, ABCD and a host of similar movements – Social Entrepreneurship, New Regionalism – all key Third Way components were not:

… a call for grassroots democracy but a response and a capitulation to the neoliberalism and its values of individualisation, marketisation and the privatisation of public life.

By focusing on “assets” rather than “solidarity”, ABCD mimics the ‘market’ speak and constructs.

Under ABCD, unemployment is not a problem but a challenge for the individual to become empowered. The state cannot achieve this, only individuals can.

They just need to identify their assets.

Of course, if a person is unemployed the state can obviously solve the problem – which is a lack of jobs.

But in ABCD that is not a solution – it is an encumberance on individual endeavour.

Macleod and Emejulu write (p.436) that:

ABCD represents a capitulation and compliance with the prevailing neoliberal reforms … Rather than seeking to organize against the elimination, reduction, and/or privatization of public services, ABCD, in theory and practice, seeks accommodation with this dominant ideological position …

It passively accepts the neoliberal narrative that the “welfare state … breeds a culture of dependency in poor communities and that the best remedy to poverty and inequality is the application of free market principles such as enterprise and entrepreneurship.”

Issues of national concern – “poverty, inequality, and asymmetries in power” become privatised matters – none of the state’s business.

When, in fact, it is the state that creates these problems through poor policy and only the state has the fiscal capacity to solve them.

My view is the the state has to work through local communities but that the latter can not function without the state.

For example, a region with high unemployment as a result of a lack of national spending relative to productive capacity can do little to change their status without damaging another region.

They might get sucked into the ‘Visitor Economy’ narratives that abound at present, which assert that local towns can become playgrounds of the rich and mobile to have motor car races through narrow suburban streets without regard for health or amenity or whatever.

And they might attract tourists and improve their employment situation. But the tourist spending comes from somewhere. And if there isn’t enough spending overall, then all the regions are doing is fighting over the shortage of funding.

When I advocate a Job Guarantee, I always emphasise that it is funded nationally (at the level of the currency-issuer) and organised locally (at the level of community need and knowledge).

ABCD and the other Third Way movements fail to recognise the essential role that the state must play to allow communities to thrive.

If a state pursues austerity and starves local regions of services and job opportunities, then, of course, the pathologies mount and the communities look like basket cases.

That sort of constraint will not be eased by identifying community assets and ignoring the political struggle against austerity.

Adopting ABCD and social capital and all the rest of the buzz just surrenders to the neoliberal approach.

Other neoliberal Trojan horses

The ABCD movement also has similarities with the so-called ‘New Regionalism’, which swept academic circles in the 1990s and beyond.

It was largely driven by case studies documenting economic successes in California (Silicon Valley) and some European regions (such as Baden Württemberg and Emilia Romagna).

The interlinked ideas that define this approach to ‘space’ were consistent with the oft-heard claim from neo-liberals that the ‘national’ level of government gets in the way of development.

It also fed into the Left narratives that globalisation had usurped the power of the nation state and that international solutions to inequality were necessary.

New Regionalism claimed that ‘the region’ had become the “crucible” (to use the words of British regional scientist John Lovering) of economic development and should be the prime focus of economic policy.

In this way, the claim was that regions had usurped the nation state as the “sites of successful economic organisation” (Scott and Storper’s words) because supply chains (in the post Fordist era) had become more specialised and flexible given the need to deal with uncertain demand conditions.

New Regionalism advocates argued that regional spaces provided the best platform to achieve flexible economies of scope that allow nations to adjust to increasingly unstable markets.

These socio-spatial processes allegedly would require localised knowledge creation, the rise of inter-firm (rather than intra-firm) relationships, collaborative value-adding chains, the development of highly supportive localised institutions and training of highly skilled labour.

These dynamics then demanded that firms to locate in clusters, often grouped by new associational typologies (for example, the use of creative talent or untraded flows of tacit knowledge) rather than by a traditional economic sector such as steel.

The new post-Fordist production modes emphasise new knowledge-intensive activities encouraging local participative systems. By achieving critical mass of local collaborators, a region could be dynamic and globally competitive.

Most these claims were based on induction of regional ‘successes’ without regard for the specific cultural or institutional contexts, and lack any coherent unifying theoretical underpinning.

It is highly disputable whether the empirical examples that were advanced to justify the claims made by New Regionalist proponents actually represented valid evidence at all.

For example, John Lovering (1999: 382) examined the claimed made in the 1990s about Wales and concluded:

If one factor has to be singled out as the key influence on Wales’ recent economic development … it is not foreign investment, the new-found flexibility of the labour force, the development of clusters and networks of interdependencies or any of the other features so often seized upon as an indication that the Welsh economy has successfully ‘globalized’. Something else has been at work which is more important than any of these, and it is a something which is almost entirely ignored in New Regionalist thought … It is the national (British) state.

(Reference: Lovering, J. (1999) ‘Theory led by policy: the inadequacies of the New Regionalism’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23, 379-395.)

That is, a supportive macroeconomic policy framework – read deficit spending from the currency-issuing government.

While many criticisms can be levelled at New Regionalism, its major weakness has always been that it perpetuated the notion that regions can entirely escape the vicissitudes of the national business cycle through reliance on a combination of foreign direct investment and export revenue.

It is a different spin (a variation) on the ‘business cycle is dead’ notion and amounts to a denial that macroeconomic policy – that is, at the national level – can be an effective response to global trends that penetrate via the supply chains defined by trade patterns to the local region.

New Regionalism thus supported neo-liberal claims that fiscal and monetary policy had become impotent and, in turn, it constructed mass unemployment as an individual phenomenon.

By ignoring the fact that mass unemployment demonstrates the unwillingness of the central government to spend sufficient amounts of currency given the non-government sector’s propensity to save, the neo-liberal position was left unchallenged and was actually reinforced.

A new style of – Say’s Law – emerged with claims that post-Fordist economies need to focus on ‘supply-side architectures’.

Similarly, ‘social entrepreneurship’, which sort to turn welfare providing groups into business instigators and entrepreneurs so they could create profits through enterprise to make up for the shortfall in welfare funding under neoliberalism.

Once again, thinking that a macro problem can be solved through individual endeavour and using all the language and framing of free market ideology.

Conclusion

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) teaches us that the fiscal space is much wider than we are led to believe.

We shouldn’t confuse the role of the state with the way the state is used.

The advocates of Asset-Based-Community-Development (ABCD), community empowerment, social capital, new regionalism, social entrepreneurship and all the rest of the ‘Third Way’ narratives just reinforce the approach that creates the problems they claim they are concerned about.

It is not the ‘state’ that is at fault but the ideologues that have taken command of the state machinery and reconfigured it to serve their own agenda, which just happen to run counter to what produces general well-being.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Who is funding these people?

Neil,

Sadly it seems that you and other UK taxpayers have for many years been funding the careers of virulent gender and race activists at UK universities.

One of these is Akwugo Emejulu who is eulogised by Prof. Mitchell in this post.

Exactly, Neil. That is precisely what I’d like to know. One weird thing is that the neoliberal ouroboros has eaten so much of itself that there is almost nothing left. Yet it will continue until it consumes itself entirely. How anyone could support such a self-defeating enterprise when the end result should be so obvious is beyond even semi-rational explanation, it seems to me.

Neil Wilson: in most countries they are funded by a variety of sources, starting with Government funding or loans (often patient capital) for “social innovation”. Such funding is not provided at anything like the levels that traditional social programs were funded, of course, but enough to allow a certain number of organizations to mount local responses, which are always inadequate in scale. They are funded through restrictive government contracts for service delivery. They are heavily funded by charities and the not-for-profit and voluntary sector (which buy into local entrepreneurship as a way to supplement the donations and government spending gaps). CSR plays a big social there. They are also funded through large foundations, usually closely-related to the financial sector, the whole 3rd-way investment scam, whereby, for a tax credit, an investor gets a stake (and often ultimately privatized ownership) of a local social venture, such as a residence for disabled. There are a number of community investment vehicles, such as Community Economic Development Investment Funds, which run local portfolios of combined for-profit and not-for-profit assets. Fourth, the co-operative sector runs a number of initiatives, and maybe cooperative development funds. And then there are hybrid models, for instance when unions join with social investors to create housing projects for retired workers. Many of these projects work well, except for the reliance on debt, and the utter inadequacy overall in spending, which means they never come close to meeting needs. And, of course, almost all of these options are highly vulnerable to cyclical downturns, and show churn at much the same rate as small businesses (cooperatives and mutuals are somewhat more sustainable).

Heart breaking..

You got to hand it to them. They knew exactly how to change the system in their favour. Doing the same now with NHS and BBC. To achieve it world wide took some effort by the way.

Will take decades to reverse what they have done. Those that would reverse it get vilified before they get anywhere near power to change things.

I cannot see any other reason than this being intentional. They know there aren’t enough jobs and that those missing out will be dependent on handouts. And they use these people as a warning for those barely hanging on and frightened of poverty to become accept any employment. It’s the opposite of empowerment. It must be intentional, creating this deprivation to push more power to the wealthy. That’s why a job guarantee with good benefits and working conditions is probably their biggest fear.

One of Bill’s better posts. No quit in him, is there? Not a single bone of capitulation, and bless him for it. My fear, however (and Bill’s as well), is that a large segment of the left HAS quit, HAS capitulated to neoliberalism. This includes not only those who buy into the third-way BS schemes Bill describes, but also those who have given up any vestige of hope for fundamental change. Such leftists seem content to be impassioned losers, endlessly railing against neoliberal outrages from a position of utter impotence–a position to which they have resigned themselves, become inured, and, worst of all, have kind of grown to like. The comfortable self-image of a virtue-signaler is damn seductive.

All the mainstream economic myths, that we have been “buying” for the last 40 years, are about, one way or the other, controlling inflation.

As we all know, inflation destroys savings for the rich and income for the poor.

OK, but what has been happening is a smooth road to deflation (at least, in the eurozone).

We assume that everybody sees deflation as a bad outcome.

But, is it for everyone?

What about the finance?

Don’t they gain with deflation?

Doens’t that means that debts will become larger, even when it’s nominal value is fixed?

What if this was/is on purpose?

Well I, for one, have only cottoned on to MMT a couple of years ago. I had no idea that there was a route to socialist Utopia. Rather than moaning about our ‘base’ for not understanding, better that we organise to spread the word. We need to reach out to the youngsters in particular. Let’s be missionaries.

I’ve already converted 2 members of the UK Communist Party:o)

Essentially what is happening is this:

These people create a game then everyone who doesn’t want to play or bad at playing is stigmatized.

stigmatization takes the form of starvation when you are a grown up.

Given that the macro approach of state investment is crucial to resolving all of these issues at the national level, do you think there are still any complementary possibilities left in a local CoOp approach to providing renewable energy through microgrids for example? Or is that all just a massive diversion?

FDR’s New Deal era power co-ops (REA) still provide power to tens of millions across rural USA but many of those Coops have been captured by local business elites.

Paulo Rodrigues, the lesson learned from Prof Michael Hudson, is that “debts that can’t be paid won’t be”. This should prove to be a sobering truth for finance.

Nothing they do helps to provide sustainable food or shelter for anyone.

Bill. I have a response to the people like the example you ran into: it’s that in 2014 the four or five Walmart Heirs acquired a fortune that equaled the wealth held by the bottom one third of the US population, at that time 105 million people. Like Trump and his son-in-law, people who have vast fortunes, and in many cases don’t pay income taxes. And there you are, you’re resenting what the poorest people in the country have – you don’t want them to have anything, blame them for you’re not having more. But don’t look down. Look up to the wealthy and the powerful. The poor don’t have your due. The people at the top took it from you without you even knowing. Each one of those heirs has about 20,000,000 times what the average person in the bottom one third has. Imagine what the ratio for the bottom 1 percent of the population. It’s in the hundreds of millions.

If you feel cheated out of your rightful wealth, don’t look at the people who survive on charity. They have almost nothing. Look at the people whose wallets are soo fat, when they sit down, it lifts their asses hundreds of miles into the sky overhead. But your point is good too. Fundamentally, that person you ran into isn’t a Christian.

Coming from one of the region you mention, Emilia Romagna I do understand what you mean with regionalism, I do have to mention thoug, that apart from the geography of the region and the natural conditions, It is very important the credit enviroment system, consisting of small local banks that does support medium and small enterprises of all kinds: family run, not for profit, Co-Ops, foreign compaies, as well as properly run public services and education.

Big companies on the other side are better served by regional and big banks, with patient capital expectation, but to persue the public national interest, they are better to be financed by the State and follow guidelines, creating research and development, providing well paid jobs and aiming at long term goals.

One of the insidious aspects of something like this ABCD is that it is true that communities do have many assets that they should be able to leverage into some form of prosperity.

However, if they cannot generate credit against these assets, they are presented with a classic bootstrap problem. You cannot make non existent money circulate through your community.

Equally, when outside parties assert rental rights against community activities there is no way to stop the local economy from deflating.

Local communities need access to encumbered seed capital.

This can only come from parliament in the end, but perhaps local development micro banks would be worth thinking about in conjunction with the JG, rather than a grandiose federally administered finance vehicle.

Certainly I mean unencumbered seed capital.

@Paulo Rodrigues,

Now, that is an *interesting* idea.

Have you considered all the effects?

An effect like when people default on their credit card debt.

Or even mortgages. Does the bank want a house that is worth less than the amount of the loan?

I have long thought that recessions are not bad for everyone. The rich (sociopaths & psychopaths) may see them as opportunities to exploit the desperate. For example to foreclose on them to take their house when they have made the payments for 25 years with just 5 years to go. Maybe they are a feature, not a bug for the rich.

.

A 2014 article by Mary Ann MacLeod and Akwugo Emejulu (behind paywall) – is worth reading if you want to learn more.

I received help from Bill’s university to avoid the paywall and was quickly able to locate here;

https://localdemocracyandhealth.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/neoliberalism-with-a-community-face-2.pdf

and this youtube of one of the authors on the same topic;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79v3kTgdmBo

I assume that the somewhat famous ‘Preston’ model in the UK should be seen as a variant of these ABCD projects?

I think that some of the commentators here have not fully appreciated that the whole social enterprise etc. approach has in many ways been a defensive, bottom up response to austerity measures — perhaps nowhere did this play out more clearly than under the right-wing separatist PQ government in Quebec in the late 1990s. Faced with contraction in federal government transfers, but also by ideological inclination, the QC government made huge cuts to economic and social investments. The not-for-profit and broader social sectors saw very well that this was a disaster, and cast about for alternative strategies — there was huge fight between the unions and their allies, who wanted to defend social infrastructure (les infrastructures sociales de base) and those who sought alternative, communitarian and largely entrepreneurial responses. The latter, who won the debate, were quite aware, for the most part, of the damage being done, but perhaps correctly judged that that was the only alternative likely to receive provincial government support of any kind. And they also felt they could no longer expect to rely on any stable government funding, and that convinced them to turn to local, communitarian options — this was a counsel of despair, but they may have been right — there were few other defensive measures available. And so one can get a kind of simulacrum of a dual economy model — the social entrepreneurs jealously but not unreasonably guard their retrenched, grassroots territory (within which things tend to work pretty well) even as broader social and economic conditions worsen. To a large extent, despite the very real horror stories that Bill sometimes relates, I think we have turned the corner. Many governments recognized, even before COVID, the inadequacy and counter-productivity of their existing market-based social supports, and had begun to institute new, broader social infrastructure responses. Some of these still partially echo 1990s and 2000s neoliberal options, but they also tend to have aspects of universality in response that were missing for two decades — take, for example, the Australian Disability Insurance Scheme — very much in a neoliberal “client service” model, but for all that pretty much universal for persons with disabilities while tailored to individuals’ specific needs (Australians please correct me if I have got that wrong).