The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Q&A Japan style – Part 5b

This is the final part of a two-part discussion about the consequences of a currency-issuing government exercising different bond-issuing options. The basic Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position is for the currency-issuing government to abandon the unnecessary practice of issuing debt (which is a hangover from the fixed exchange rate, gold standard days). Currency-issuing governments should use that capacity to advance general well-being and providing corporate welfare to underpin and reduce the risk of speculative behaviour in the financial markets does not serve any valid purpose. However, when we introduce real world layers (politics, etc) we realise that some pure MMT-type options are not possible. This question introduces just such a case in Japan. Given the political constraints, we are asked to choose between two options for central bank conduct, when the government does issue debt: (A) Buy it all up in the secondary bond markets. (B) Leave it in the non-government sector. In this final part, I go through some of the considerations that might influence that choice.

Recap

In the first part – Q&A Japan style – Part 5a (December 3, 2019) – the proposition was put that in Japan both sides of politics – the progressive Left parties and the conservative parties on the Right – eschew any notion that:

(a) the Japanese government runs deficits but dispenses with the unnecessary practice of matching those deficits with debt-issuance. This is the pure Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position.

OR:

(b) the Japanese government issues debt, which is then bought on secondary bond markets by the Bank of Japan.

I find this to be a very odd position for progressives to take.

Certainly, a person with an MMT understanding would realise that the first option is desirable and the second option has no fundamental negative consequences, but does allow the central bank to control bond yields (and prices).

We learned that the considered opinion is that the only politically acceptable option is that the government issues bonds to the non-government sector (currently via an auction process), where selected financial institutions are licensed to ‘make the market’, by placing bids for volume and price (yield), which then determines the overall yield on each bond issue.

Under this ‘politically acceptable’ option, we also learned that there is considerable disagreement as to what the central bank should do in this case.

I was asked by my Japanese friends to discuss two options from an MMT perspective:

(A) Should the central bank purchase these bonds in the secondary market which has the effect of transferring the interest return to the consolidated government sector and allows the central bank to control all yields and hold rates at zero if they desire?

OR:

(B) Should the central bank refrain from purchasing these bonds in the secondary market and leave the bond holders in the non-government sector to earn interest returns and principal payment on maturity?

It transpires that many progressives in Japan oppose Option A because they believe by creating bank reserves the policy approach plays into the hands of the so-called New Keynesian ‘reflationists’ (such as Paul Krugman) who were prominent in the ‘Great Stagnation’ debate in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But the rival view is that, under Option (B), the central bank loses control of interest rates, and, ultimately, yields become market determined, which may ultimately lead to rising interest rates.

In this sense, many marginal firms who are just surviving in the present situation, would be adversely affected by interest rate changes, which would have the consequence of reducing investment and overall aggregate demand.

So the question really was about what might an MMT perspective bring to this debate?

In – Part 1 (December 3, 2019) – I dealt with the so-called New Keynesian ‘reflationists’.

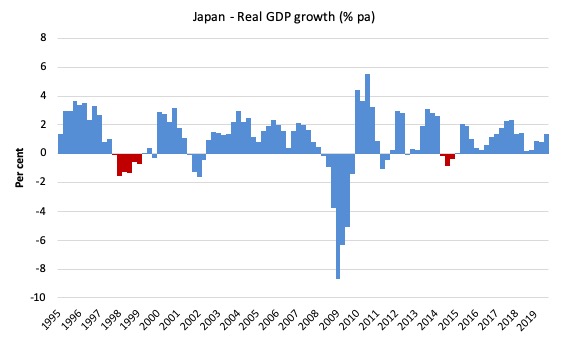

These characters correctly understood that the in the period after the first consumption tax hike (May 1997), the Japanese economy went into a recession that lasted for six quarters (from December-quarter 1997 to the March-quarter 1999) and then struggled to resume growth for the rest of 1999.

This was the period that became known as the ‘Great Stagnation’ and attracted the attention of the ‘reflationists’ from within Japan and abroad.

The following graph shows quarterly real GDP growth from 1995 to the September 2019 (using Cabinet data) with the consumption tax hikes impacts shown in the red bars.

It was clearly a recession induced by poorly constructed fiscal policy. There was no need at all to increase the consumption tax. The Japanese government bowed to pressure from conservative economists who spun the story that it was running excessive deficits and building up too much debt, which would eventually create uncontrollable inflation, higher interest rates and bond yields, and ultimately, government insolvency.

All the usual fake narratives about currency-issuing governments.

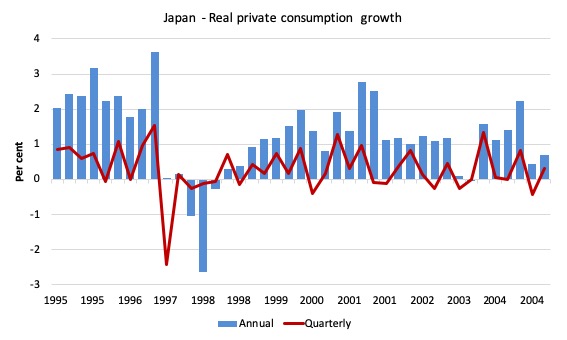

The May 1997 consumption tax hike caused an almost immediate reaction in real private consumption expenditure, which fell by 0.66 per cent in the June-quarter 1997 – a substantial immediate response.

The decline in consumption expenditure growth resonated for several quarters.

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in real private consumption expenditure from the March-quarter 1995 to the March-quarter 2005.

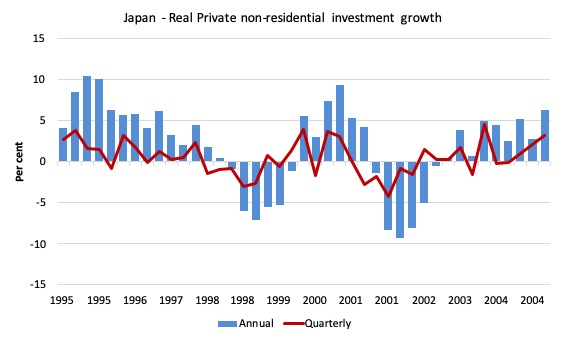

Similarly, as would be expected, as the collapse in consumption expenditure created excess capacity, business investment also fell sharply as a generalised pessimism set in.

The following graph shows the quarterly growth in real private non-residential investment expenditure from the March-quarter 1995 to the March-quarter 2005.

The negative response was a lagged reaction to the downturn and investment spending didn’t recover as quickly because the renewed growth in late 1998 was accommodated by existing productive capacity.

So trying to suggest that the prolonged recession was due to a ‘mythical’ real interest rate being too high, because the inflation rate was too low relative to the near zero nominal interest rates (the ‘reflationists’ ‘liquidity trap’ fantasy) really missed the point.

And trying to suggest that if the Bank of Japan engaged in large-scale bond-buying in return for bank reserves would lift the inflation rate significantly – via the erroneous money multiplier and Quantity Theory of Money theories – was always going to fail.

The Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists made that point at the time and many times since.

The ‘reflationists’ were still trotting out these ridiculous ideas during the GFC.

I remind readers of the analysis one Paul Krugman made of the Japanese situation in May 1998 – Japan’s Trap – which echoed what he was also saying during the GFC and since.

He dramatically failed to understand the nature of the problem in Japan in 1998 and recommended a reliance on monetary policy.

In terms of his prescription he claims that his model was subject to “Ricardian equivalence, so that tax cuts have no effect”.

Further, he claims that government spending stimulus would have some impact in the immediate context but would “would be partly offset by a reduction in private consumption expenditures”.

To understand how ridiculous the notion of Ricardian equivalence is please read these blog posts (among others):

1. Ricardian agents (if there are any) steer clear of Australia (June 9, 2014).

2. Ricardians in UK have a wonderful Xmas (January 24, 2011).

3. Mainstream macroeconomics credibility went out the window years ago (October 2, 2017).

Krugman also said in 1997 that while fiscal policy stimulus might provide some marginal short-term growth, previous government spending:

… has been notoriously unproductive: bridges more or less to nowhere, airports few people use, etc … But there is a government fiscal constraint …

He went on to advocate the ‘reflationist’ strategy and claimed that that monetary policy had been ineffective because:

… private actors view its … [Bank of Japan] … actions as temporary, because they believe that the central bank is committed to price stability as a long-run goal. And that is why monetary policy is ineffective! Japan has been unable to get its economy moving precisely because the market regards the central bank as being responsible, and expects it to rein in the money supply if the price level starts to rise.

The way to make monetary policy effective, then, is for the central bank to credibly promise to be irresponsible – to make a persuasive case that it will permit inflation to occur, thereby producing the negative real interest rates the economy needs. This sounds funny as well as perverse … [but] … the only way to expand the economy is to reduce the real interest rate; and the only way to do that is to create expectations of inflation.

History tells us he was completely wrong in his diagnosis at the time as were all the ‘reflationists’.

The only thing that got Japan moving again was a renewed commitment to using fiscal policy to support growth.

and so it was no surprise that the QE they were urging the Bank of Japan to engage in as a means of lifting the inflation rate would fail

In his 2003 book – Balance Sheet Recession: Japan’s Struggle with Uncharted Economics and its Global Implications – Richard Koo wrote:

The reason why quantitative easing did not work in Japan is quite simple and has been frequently pointed out by BOJ officials and local market observers: there was no demand for funds in Japan’s private sector.

In order for funds supplied by the central bank to generate inflation, they must be borrowed and spent. That is the only way that money flows around the economy to increase demand. But during Japan’s long slump, businesses left with debt-ridden balance sheets after the bubble’s collapse were focused on restoring their financial health. Companies carrying excess debt refused to borrow even at zero interest rates. That is why neither zero interest rates nor quantitative easing were able to stimulate the economy for the next 15 years.

While I differ with Richard Koo on other issues, his analysis of the ‘Great Stagnation’ was correct and made Krugman and his fellow ‘reflationists’ look like fools.

Analysing the Options

So what does this all mean for how we should think about the central bank operations under the only ‘politically acceptable’ option that the Japanese government continue issuing debt.

The two options for the central bank in this situation are:

(A) Should the central bank purchase these bonds in the secondary market which has the effect of transferring the interest return to the consolidated government sector and allows the central bank to control all yields and hold rates at zero if they desire?

OR:

(B) Should the central bank refrain from purchasing these bonds in the secondary market and leave the bond holders in the non-government sector to earn interest returns and principal payment on maturity?

There is no MMT position on this.

What an MMT understanding provides is a framework for assessing the consequences of each choice, which would then reflect the social and political judgement of those consequences.

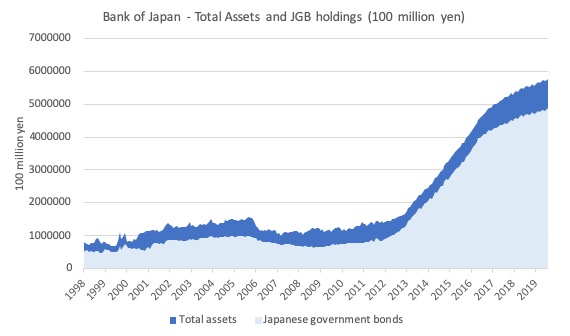

Option (A) is the current orthodoxy in Japan as is evidenced by the following graphs.

The first shows the Bank of Japan’s Balance Sheet assets from April 1998 to November 2019. The light blue area indicates the Bank’s holdings of outstanding Japanese government bonds (JGBs).

So the rather dramatic increase in the total assets held by the Bank is largely due to the various QE (bond buying) programs it has been pursuing over the last two decades.

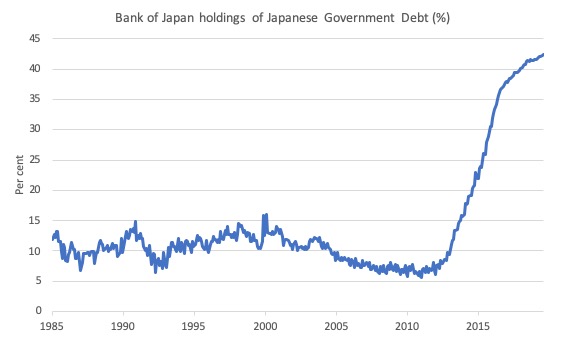

The next graph shows the proportion of total outstanding JGBs held by the Bank of Japan from 1985 to September 2019.

The Bank currently holds 42.37 per cent of the total.

What these graphs (and the underlying data) tells us that the Bank of Japan’s strategy to buy JGBs in large volumes in order to, in their words, increase the inflation rate, has failed.

This demonstrates how ineffective monetary policy is in influencing the path of the inflation rate, despite the massive increase in central bank assets.

There is no relationship between the evolution of the monetary base (driven by the Bank’s purchases of JGBS in large volumes) and the evolution of the inflation rate.

The latest data on inflation expectations is also indicative that the QE policies are not having the desired effect.

The New Keynesian mainstream macroeconomics further suggests that prices are adjusted to accord with expected inflation. With rational expectations, the mainstream models predict that inflation will respond one-for-one with shifts in expected inflation.

The Bank of Japan has been trying to manipulate that ‘theoretical claim’ in real space through its QE experiments but has clearly not succeeded.

Please read my blog post – Japan still to slip in the sea under its central bank debt burden (November 22, 2018) – for more discussion on this point.

An MMT understanding provides us with an explanation of why this strategy (independent of fiscal policy) will be ineffective.

Income implications

What we know is that:

1. The QE strategy has been maintain long-term interest rates around zero. Why? In the hope that it will stimulate investment spending. But if the revenue-earning outlook is pessimistic, borrowers will not seek credit even at low interest rates. This is the point the ‘reflationists’ could not grasp.

2. The QE strategy has thus reduced income flows that would normally go to the non-government sector as a result of their bond holdings in the form of interest payments.

3. To offset that impact, central banks pay interest on excess reserves, to assist in maintaining the profitability of the financial institutions in question.

In Japan, there is a complex system known as the Complementary Deposit Facility – which provides a facility where the Bank of Japan can pay interest on excess reserve balances (above required reserves) for financial institutions that have current balances with the Bank.

However, since January 2016, when the QQE program drove interest rates negative, “excess reserves … have been divided into three tiers, to which a positive interest rate, a zero interest rate, and a negative interest rate are applied, respectively.”

The aim is to provide an incentive to banks carrying excess reserves to loan them to other financial institutions in need of reserves – ” as long as the rate exceeds the rate applied to the Policy-Rate Balances” (those that attract the negative interest rate).

The Bank says that “Rather than merely holding surplus funds in current accounts at the Bank, such transactions improve financial institutions’ profits.”

When the “Policy-Rate Balances increase as a whole … this exerts downward pressure on money market rates.” They increase, in part, as a result of the “Bank’s Japanese government bond purchasing operations”.

To protect “the profits of financial institutions”, the Bank makes adjustments to the benchmarks that determine when the negative interest rate (‘tax’) will cut in, “so as to avoid drastic changes in the Policy-Rate Balances”.

The most recent review was on September 19, 2019, see – Review of the Benchmark Ratio Used to Calculate the Macro Add-on Balance in Current Account Balances at the Bank of Japan – which increased the Benchmark Ratio to 37 per cent (from 36 per cent).

But, of course, the payment on excess reserves only flow to the financial institutions that have accounts with the Bank of Japan.

But, that aside, the payment of interest on excess reserves blurs the difference between Option (A) and Option (B).

The difference that remains is the possible capital gains on the assets held.

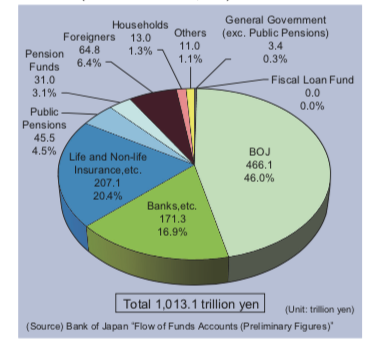

The outstanding JGBs not held by the Bank of Japan or other government agencies, are mostly held by various City Banks and Long-term Credit banks, Trust Banks, Regional Banks, and other financial institutions.

This graph (created from the Flow of Funds data available from the Bank of Japan) published in the – 2019 Debt Management Report – issued by the Ministry of Finance, shows the breakdown of JGB holders as of December 2018.

Now, ask yourself, why would these holders sell to the Bank of Japan?

Answer: because the demand from the QE programs push the price of the bonds up in the secondary market and create capital gains for the sellers.

The capital gain will reflect the maturity (principle) value of the bond plus the expected discounted flow of the interest payments that the holder would receive adjusted for inflation risk.

If there was a serious shortfall in the realisable capital gain relative to the principle/interest payments from holding to maturity, then why would a holder choose to sell – unless they had short-run liquidity issues that required emergency liquidation.

The point is that Option (A) and Option (B) may, in fact, not be very different in overall outcome.

1. Option (A) shifts liabilities to the non-government at the central bank from an account labelled ‘Outstanding JGBs’ to ‘Reserves’ and the income flows associated from ‘Interest payments on outstanding debt’ to ‘Interest payments on excess reserves’.

2. It also ensures that the secondary markets will be indifferent to selling the asset to the Bank at a price that reflects the return they would expect by holding the asset and earning interest until maturity (Option (B)).

Further, a progressive objection to Option (A) should not be motivated by the fact that the ‘reflationists’ suggested the strategy but rather that it doesn’t actually achieve its stated purposes.

Implications for liquidity management

Under Option (B), the government cedes control of yield determination at the regular JGB auctions to the private bond markets.

Option (A) allows the central bank to control all primary issue yields, indirectly, through influencing bond prices and yields in the secondary bond market.

At the limit, the central bank can set all rates along the yield curve (at all maturities) if it so chooses through QE-type purchases.

That control lapses under Option (B).

If yields are set in the private auction markets and then subject to speculative transactions in the secondary bond markets, then, clearly, there is the possibility that rates will rise over time.

The concern expressed in the original question (see Part 5a) is that this has the potential to damage marginal firms contemplating investment decisions.

While I considered the question of the sensitivity of investment spending in this blog post – Q&A Japan style – Part 1 (November 4, 2019) – and concluded there are solid arguments that can be made to suggest the sensitivity is low, it remains a possibility that such a negative impact would arise.

That concern does not apply under Option (A) because the yield curve always remains under the control of the central bank.

We should also distinguish between QE-type behaviour by the central bank and the more standard Open Market Operations (OMO), which, historically, have formed the basis of the liquidity management function of the central bank.

OMO involves the central bank buying and selling government bonds on the open market to manage bank reserves by influencing the price and yield of certain government bonds.

OMO is part of the strategy central banks use to ensure the short-term interbank rates (and subsequent longer maturity rates) are in line with the policy rate that it chooses.

OMO involves the central bank managing reserves by exchanging government securities for reserves (in either direction) with financial institutions that maintain accounts (current balances in the Japanese context).

The two arms of government (treasury and central bank) have an impact on the stock of accumulated financial assets in the non-government sector and the composition of the assets.

The government deficit (treasury operation) determines the cumulative stock of financial assets in the private sector, whereas, central bank decisions then determine the composition of this stock in terms of notes and coins (cash), bank reserves (clearing balances) and government bonds.

Money markets are where commercial banks (and other intermediaries) trade short-term financial instruments between themselves in order to meet reserve requirements or otherwise gain funds for commercial purposes.

All these transactions net to zero. At the end of each day commercial banks have to appraise the status of their reserve accounts.

Those that are in deficit can borrow the required funds from the central bank, usually at a penalty rate.

Alternatively banks with excess reserves are faced with earning nothing or some support rate on these excess reserves if they do nothing.

Clearly it is profitable for banks with excess funds to offload those reserves via loans to banks with deficits at market rates. Transactions in the interbank market necessarily net to zero and cannot clear the system-wide surplus.

Competition between banks with excess reserves for custom puts downward pressure on the short-term interest rate (overnight funds rate) and depending on the state of overall liquidity may drive the interbank rate down below the operational target interest rate.

When the competitive pressures in the overnight funds market drives the interbank rate below the desired target rate, the central bank drains the excess liquidity by selling government debt.

This is a different motivation to that used to justify QE, which broadens the scope of the standard OMO to more comprehensively control yields and bond prices.

When the government runs a deficit that is matched by bond-issuance, the non-government sector swap reserves for the bonds.

If the deficit spending then stimulates further excess reserves, then the central bank has to drain them or pay the support rate if it is to maintain control of its monetary policy target.

In the case of Japan, the Bank of Japan has effectively maintained zero short-term rates aligned with its policy rate by not draining all excess reserves.

Option (A) is an extreme version of this. Option (B) is not incommensurate with the Bank of Japan maintaining the tools necessary to manage bank reserves.

Some might raise concerns under Option (A) about the Bank of Japan incurring capital losses should yields subsequently rise while they have massive JGB holdings.

Those who do not understand the concept of a currency-issuer cannot also understand why negative capital for a currency-using business is problematic but of no application or relevance to a central bank.

Please read my blog post – The ECB cannot go broke – get over it (May 11, 2012) – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

My preference is clearly for the government not to issue debt to match any deficit spending. It is unnecessary and amounts to corporate welfare.

But, when we introduce real world layers (politics, etc) we realise that some pure MMT-type options are not possible.

This question introduces just such a case in Japan.

Given the political constraints, we are asked to choose between two options for central bank conduct, when the government does issue debt.

(A) Buy it all up in the secondary bond markets.

(B) Leave it in the non-government sector.

My preference is for Option (A) because I also have a preference for zero short-term interest rates and Option (B) makes that aspiration difficult to manage.

But, equally, I resent handing out capital gains to bond holders (which makes the corporate welfare even more advantageous) and absorbs the risk of holding the bonds within the government sector.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

As I say, I’m not an economist.

Above there are 2 graphs with blue vertical bars and a red zig-zag line. The bars are ‘annual’ and the red line is ‘quarterly’. Across the bottom are the years.

To me it looks like there are 3 bars {40} for each year {14}. and some years may-be/are partial.

Can someone explain to me what ‘annual’ means in those graphs and what ‘quarterly means too.

Thanks.

There is no difference between domestic savings and foreign sector savings the central bank treats them the same.

Neil Wilson came up with an idea that we should just go back to using the Ways and means account before the Maastricht treaty banned the use of it..

” The Ways and Means Account is just an infinite overdraft with the Central Bank, and it grows over time to balance the net-savings of the non-government sector just as the Gilt stock does now.

HM Treasury simply doesn’t issue any Gilts any more. Any funding of private pensions in payment should be done by offering annuities at National Savings, which would also have the neat side effect of ‘confiscating’ net savings and making the deficit go down.

It’s irrelevant what interest BoE charges on the ‘Ways and Means’ account since any profit the BoE makes from it goes back to HM treasury anyway. So it can 50% if that gives the necessary level of satisfaction to mainstream economists.

What you have is a standard intra-group loan account between a principal entity (HM Treasury) and its wholly-owned subsidiary. Normally those sort of loans are interest free for the fairly obvious reason that interest charging is utterly pointless, and they are perpetual for the same reason. Rolling over is totally pointless.

Any term money can then be issued to the commercial banks directly by the Bank of England – up to three month Sterling bills.

The interest rate to the banks from the Bank of England is a matter of the ‘capital development of the economy’. Almost certainly it would be ZIRP.

If you are a member of a pension scheme then the savings of the current generation, plus the interest on Gilts and any income from the other assets owed pay the pensions of the current generation of pensioners. They are all, in effect, private taxation schemes that circulate money around the system.

You’ll note that when there was a threat of people failing to save in pensions, the government introduced compulsory retirement saving – which is of course a privatised hypothecated tax.

So in essence rather than the assets of a pension scheme being used to purchase Gilts, the assets would be used to purchase an annuity from the government dedicated to an individual. The result is that rather than the private pension receiving Gilt income from the state, to then pass onto the pensioner, the state would cut out the middleman (and their cut) and pay the pensioner directly as an addition to the state pension.

There’s a whole private pension industry out there literally doing absolutely nothing of any real value. They can’t provide a guaranteed income in retirement without state backing in the form of Gilts. So what is exactly the point of having them? “

The left have to be prepared to take on the FIRE sector lobbying groups or nothing Changes. No point at all fiddling around the edges turning a sponge cake into a fairy cake.

If the lobbying groups keep enriching their power a few years down the line the liberal left and liberal right will be running the show again. Which means another 30 years of minimum choice at the election box. A cigarette paper between what is on offer.

A sure sign that democracy has been hijacked.

Derek, with regard to the ‘Ways and means’ facility, Nigel Hargreaves mentioned to me some time ago about a Protocol in the Lisbon Treaty that seems to modify Art. 123 in regards to allowing the facility outside the Eurozone.

Bill will know what the real-world implications of this are but on the surface, it appears to permit it as long as the UK is outside the EZ .

’10. Notwithstanding Article 123 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 21.1 of the Statute, the Government of the United Kingdom may maintain its “ways and means” facility with the Bank of England if and so long as the United Kingdom does not adopt the euro.’