The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Ricardians in UK have a wonderful Xmas

The latest data from the UK provides us with further evidence that mainstream economic theory and its policy advice is dangerous and should be disregarded. We are now some six months or more into the period of fiscal austerity in Britain even though many of the cut backs and tax hikes etc have not yet been introduced. But the British households and firms have known since the election result in May what was ahead of them and so have had time to make adjustments to their spending and saving patterns to take into account the expected future. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) predicted that as a result of the fiscal austerity plans, the British economy would slow down again as private consumers and firms cut back on their own spending driven strongly by the fear of unemployment and flat sales conditions that accompany that situation. Mainstream theory pushed the notion of Ricardian Equivalence which claims that that private spending is weak because we are scared of the future tax implications of the rising budget deficits. But, the overwhelming evidence shows that firms will not invest while consumption is weak and households will not spend because they scared of becoming unemployed and are trying to reduce their bloated debt levels. Recent data shows that the Ricardians in UK have had a wonderful Xmas. Not!

I have provided this quote previously but it is always worth reflecting on at regular intervals. It describes how mainstream economics uses methods and approaches that renders it unable to embrace real world problems. It was written by Post Keynesian economists Paul Davidson for the book by Bell and Kristol The Crisis in Economic Theory (Basic Books, 1981, p.157):

There are certain purely imaginary intellectual problems for which general equilibrium models are well designed to provide precise answers (if anything really could). But this is much the same as saying that if one insists on analyzing a problem which has no real world equivalent or solution, it may be appropriate to use a model which has no real-world application. By the same token, if a model is designed specifically to deal with real-world situations it may not be able to handle purely imaginary problems.

Post Keynesian models are designed specifically to deal with real-world problems. Hence they may not be very useful in resolving imaginary problems that are often raised by general equilibrium theorists. Post Keynesians cannot specify in advance the optimal allocation of resources over time into the uncertain, unpredictable future; nor are they able to determine how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. On the other hand, models designed to provide answers to questions of the angel-pinhead variety, or imaginary problems involving specifying in advance the optional-allocation path over time, will be unsuitable for resolving practical, real-world economic problems.

MMT is in the Post Keynesian tradition and therefore does not concern itself with computing “how many angels can dance on the head of a pin”. It is not an imaginary approach that deals with imaginary problems. It is about the real world and starts with some basic macroeconomic principles like – spending equals income.

The basic macroeconomic rule – spending equals income – is being ignored by governments who have been captured by the neo-liberal dogma that self-regulating private markets will deliver prosperity to all if only governments reduce regulation and run budget surpluses with low taxation.

There have been scores of mainstream economic lies that this crisis has exposed including deficits cause inflation; deficits cause interest rates to rise; there is a money multiplier; etc.

But the most basic neo-liberal lie is that if governments cut their spending the private sector will fill the gap. Mainstream economic theory claims that that private spending is weak because we are scared of the future tax implications of the rising budget deficits. But, the overwhelming evidence shows that firms will not invest while consumption is weak and households will not spend because they scared of becoming unemployed and are trying to reduce their bloated debt levels.

When we think of a theoretical model it has often been claimed that the assumptions do not have to be “realistic” for the model to have predictive value. This was the approach spelt out in Milton Friedman’s famous 1953 article – The Methodology of Positive Economics – you can find the article HERE.

This is an oft-cited article when the mainstream claim that what they do is value free – Friedman said “Positive economics is in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments”.

But the classic idea in that article which the mainstream continually bring up when criticisms such as that noted by Davidson above are made is captured by Friedman in this way:

In so far as a theory can be said to have “assumptions” at all, and in so far as their “realism” can be judged independently of the validity of predictions, the relation between the significance of a theory and the “realism” of its “assumptions” is almost the opposite of that suggested by the view under criticism. Truly important and significant hypotheses will be found to have “assumptions” that are wildly inaccurate descriptive representations of reality, and, in general, the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions (in this sense) … The reason is simple. A hypothesis is important if it “explains” much by little, that is, if it abstracts the common and crucial elements from the mass of complex and detailed circumstances surrounding the phenomena to be explained and permits valid predictions on the basis of them alone. To be important, therefore, a hypothesis must be descriptively false in its assumptions …

So Friedman is extolling the virtues of the predictive power of a theory or hypothesis rather than how you get to make the predictions. If it turns out that the predictions are empirically sound then the theory is useful – which is a very instrumental way of conducting science.

According to Friedman, one should not evaluate a “theory” by determining whether the assumptions accord with reality. He even thinks that “wildly inaccurate assumptions” are okay if they lead to useful predictions.

I have long taught that models are always “false” in the sense that we wouldn’t know what is truth anyway if we confronted it. So I have sympathy for the view that a theory is as good as its ability to capture the key empirical outcomes and do better at that than competing theories using conventional statistical and econometric diagnostic tools as a guide to making that assessment of relative worth. I won’t go into that discussion here as it gets fairly technical (and boring).

So I agree that we should not judge a model’s usefulness on the simplicity or abstractness of its reasoning. But model building is also an iterative process whereby a researcher pushes out a conjecture and considers who well it encompasses the existing knowledge and the known facts. A conjecture that cannot help us understand the known facts (that is, makes predictions that are violated by the known facts) is not worth much in terms of its knowledge potential. So we are often making conjectures and seeing how they stack up – this is not falsification in the Popperian sense which is a fundamentally flawed conceptualisation of scientific endeavour.

Rather it is a iterative process where assumptions and structures might be varied if a conjecture is unsound (that is, cannot embrace the facts). Friedman and his cohort employed this approach as much as anyone which makes his strong viewpoint that the assumptions do not matter appear rather inconsistent. But that is an aside.

But there is a more substantive point about the assumptions used in a model. One always has to be cognisant of the actual assumptions that are required for the logical conclusions (and predictions) to hold. If they do not hold then the logical conclusions cannot then be maintained with any “authority”. Despite Friedman’s famous “what if” claim that we should only focus on the predictions even if the assumptions are plainly wrong, you can be almost certain that if the assumptions are crazy then the conclusions will be worse.

The point is that if a predictive structure relies on the set of assumptions to make the conjectures and if you cannot glean the same set of predictions if one or more of the assumptions are relaxed or clearly shown to be invalid (in terms of human behaviour etc) then the assumptions matter for the predictions.

The notion of Ricardian Equivalence falters on these grounds even before we examine its predictive capacity.

The modern version of Ricardian Equivalence was developed by Robert Barro at Harvard. For non-economists – this piece of neo-liberal dogma says that the non-government sector (consumers explicitly) having internalised the government budget constraint will negate any government spending increase whether the government “finances” its spending via taxes or borrowing. So if the government spends and borrows, consumers will anticipate higher future taxes and spend less now offsetting the stimulus).

The logic that the model is based on is as follows. First, start with the mainstream view that: (a) In the short-run, budget deficits are likely to stimulate aggregate demand as long as the central bank accommodates the deficits with loose monetary policy; and (b) in the long-run, the public debt build-up crowds out investment because it competes for scarce savings.

This view is patently false because deficits put downward pressure on the interest rate and central banks issue debt to stop that downward pressure from arresting control from them of their target interest rate. Please read the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion of that point.

Further, there is no finite pool of saving except at full employment. Income growth generates its own saving (investment brings forth its own saving) and governments just borrow back the funds (drain bank reserves) $-for-$ that the deficits inject anyway. Banks create deposits when they create loans not the other way around. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion of that point.

But let’s stick with the mainstream argument for the moment so we can understand what Ricardian Equivalence is about. Barro then said that the government does “our work” for us. It spends on our behalf and raises money (taxes) to pay for the spending. When the budget is in deficit (government spending exceeds taxation) it has to “finance” the gap, which Barro claims is really an implicit commitment to raise taxes in the future to repay the debt (principal and interest).

Under these conditions, Barro then proposes that current taxation has equivalent impacts on consumers’ sense of wealth as expected future taxes.

For example, if each individual assesses that the government is spending $500 this year per head and collects $500 per head “to pay for it” then the individual will cut consumption by $500 because they are worse off.

Alternatively, if the individual perceives that the government has spent $500 this year but proposes to tax him/her next year at such a rate that the debt will be cleared then the person will still be poorer over their lifetime and will probably cut back consumption now to save the money to pay the higher taxes.

So the government spending has no real effect on output and employment irrespective of whether it is “tax-financed” or “debt-financed”. That is the Barro version of Ricardian Equivalence.

The models suggest that individuals assess the total stream of income and taxes over their lifetime in making consumption decisions in each period.

On tax cuts, Barro wrote (in ‘Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?’, Journal of Political Economy, 1974, 1095-1117):

This just means that lower taxes today and higher taxes in the future when the government needs to pay the interest on the debt; I’ll just save today in order to build up savings account that will be needed to meet those future taxes.

So what are the assumptions that Barro makes which have to hold in entirety for the logical conclusion he makes to follow? Note this is not to say that any of his reasoning is a sensible depiction of the basic operations of a modern monetary system. It just says that if we suspend belief and go along with him for the ride then the only way he can derive the predictions from his model that he does requires the following assumptions to hold forever.

Should any of these assumptions not hold (at any point in time), then his model cannot generate the predictions and any assertions one might make based on this work are groundless – meagre ideological statements. That is, one could not conclude that it was this particular model that was “explaining” the facts even if the predictions of the model were consistent with the facts. This brings us into the problem of observational equivalence haunts modellers like me. It is basically a problem where two competing theories are “consistent” with the same set of facts and there is no way of disentangling the theories on empirical grounds. I won’t go into the technicalities of that problem.

As I have noted previously, the predictions forthcoming by those who adhere to the notion of Ricardian Equivalence rely on the following assumptions holding always.

First, capital markets have to be “perfect” (remember those Chicago assumptions) which means that any household can borrow or save as much as they require at all times at a fixed rate which is the same for all households/individuals at any particular date. So totally equal access to finance for all.

Clearly this assumption does not hold across all individuals and time periods. Households have liquidity constraints and cannot borrow or invest whatever and whenever they desire. People who play around with these models show that if there are liquidity constraints then people are likely to spend more when there are tax cuts even if they know taxes will be higher in the future (assumed).

Second, the future time path of government spending is known and fixed. Households/individuals know this with perfect foresight. This assumption is clearly without any real-world correspondence. We do not have perfect foresight and we do not know what the government in 10 years time is going to spend to the last dollar (even if we knew what political flavour that government might be).

Third, there is infinite concern for the future generations. This point is crucial because even in the mainstream model the tax rises might come at some very distant time (even next century). There is no optimal prediction that can be derived from their models that tells us when the debt will be repaid. They introduce various stylised – read: arbitrary – time periods when debt is repaid in full but these are not derived in any way from the internal logic of the model nor are they ground in any empirical reality. Just ad hoc impositions.

So the tax increases in the future (remember I am just playing along with their claim that taxes will rise to pay back debt) may be paid back by someone 5 or 6 generations ahead of me. Is it realistic to assume I won’t just enjoy the increased consumption that the tax cuts now will bring (or increased government spending) and leave it to those hundreds or even thousands of years ahead to “pay for”.

Certainly our conduct towards the natural environment is not suggestive of a particular concern for the future generations other than our children and their children.

If we wrote out the equations underpinning Ricardian Equivalence models and started to alter the assumptions to reflect more real world facts then we would not get the stark results that Barro and his Co derived. In that sense, we would not consider the framework to be reliable or very useful.

But we can also consider the model on the basis of how it stacks up in an empirical sense. When Barro released his paper (late 1970s) there was a torrent of empirical work examining its “predictive capacity”.

It was opportune that about that time the US Congress gave out large tax cuts (in August 1981) and this provided the first real world experiment possible of the Barro conjecture. The US was mired in recession and it was decided to introduce a stimulus. The tax cuts were legislated to be operational over 1982-84 to provide such a stimulus to aggregate demand.

Barro’s adherents, consistent with the Ricardian Equivalence models, all predicted there would be no change in consumption and saving should have risen to “pay for the future tax burden” which was implied by the rise in public debt at the time.

What happened? If you examine the US data you will see categorically that the personal saving rate fell between 1982-84 (from 7.5 per cent in 1981 to an average of 5.7 per cent in 1982-84).

In other words, Ricardian Equivalence models got it exactly wrong. There was no predictive capacity irrespective of the problem with the assumptions. So on Friedman’s own reckoning, the theory was a crock.

Once again this was an example of a mathematical model built on un-real assumptions generating conclusions that were appealing to the dominant anti-deficit ideology but which fundamentally failed to deliver predictions that corresponded even remotely with what actually happened.

Barro’s RE theorem has been shown to be a dismal failure regularly and should not be used as an authority to guide any policy design.

Please read my blog – Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! – for more discussion on this point.

And now to Britain …

Ricardian notions have underpinned the push for fiscal austerity in Britain. The Government has claimed that by cutting the deficit and reducing the public debt ratio, private spending will rise to more than fill the gap.

The UK Guardian article (January 21, 2011) – Retail sales suffer worst December since 1998 – tells the story by itself.

Britain suffered “Arctic conditions in the run-up to Christmas” while “retail sales suffered their worst December since 1998 after a sharp drop in sales of food and fuel”.

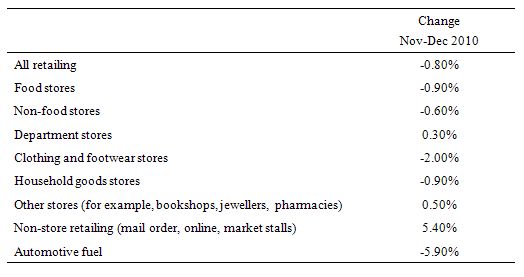

The following Table shows the monthly change (seasonally adjusted) across the main retail components.

The Retail Sales, December 2010 data from the Office for National Statistics blamed the weather – people not being able to get out and the rising prices (driven largely by tax increases as part of the austerity push). But when you look at annualised changes, the outcome was the “weakest annual performance for any December since 1998” so the transitory weather conditions can only be part of the story.

The ONS said that:

This is the 11th consecutive fall in food store sales and the lowest on record.

Apparently,”the belt tightening started a little earlier than expected” in Britain. Excuse me! Run that by me again … “the belt tightening started a little earlier than expected”.

No, the mainstream macroeconomists advising the errant British government have been predicting exactly the opposite. A key rationale for the claim that the implementation of the fiscal austerity program would actually promote growth was the argument that British consumers were poised to increase spending but were reluctant to because they were scared of future tax increases as a result of the increasing budget deficits.

This is the Ricardian Equivalence theory that is the centrepiece of the mainstream economics claim that fiscal deficits are not expansionary and vice versa. More in a moment on that.

The UK Guardian claims that:

Households are expected to cut back sharply in coming months, under pressure from rising taxes, job insecurity and higher living costs, in particular food and petrol. This will be compounded by the full impact of the government’s austerity measures, which are expected to lead to thousands of public sector job losses.

So in that assessment – British households are not Ricardian in their behaviour. So who is?

The poor retail sales will clearly impact on the upcoming December quarter GDP figures. The UK Guardian article (January 23, 2010) – GDP figures likely to show zero growth – reported that “(f)igures out this week are expected to show that Britain’s economy came to a virtual standstill in the last three months of the year”.

Again there was a suggestion that we blame “the snow for the slump in sales” which, if the dominant cause, would not allow us to conclude that the fiscal austerity is damaging consumer sentiment as per my prediction.

But the related evidence is very damaging. The Guardian says that “(c)onstruction, which grew strongly in the first half of 2010, has gone back into recession in recent months, while surveys of the services sector, which makes up 70% of the economy, have shown it weaken”. That is not a December snow-storm effect!

Further, “lending figures from the Bank of England and the Council of Mortgage Lenders only added to the gloom. Bank officials said lending to businesses shrank by £5bn in the three months to November. The CML reported a dive in mortgage lending as sales remained subdued”. That is not a December snow-storm effect!

But most damaging to the mainstream theory is the latest survey data from the – Markit Household Finance Index – which provides indicators of consumer sentiment and allows us to understand more fully what consumers are likely to do and why.

In the December release we read that:

With the fiscal taps set to run cold in 2011, it’s unsurprising that people are unwilling to make major purchases, even with the prospect of VAT rising to 20% in January, and remain downbeat about the outlook for their finances.

Regional disparities are likely to become increasingly evident as next year progresses, with areas that are reliant on the public sector (either as an employer or source of contracts to business) likely to see the greatest pressure on their household finances.

So prior to the bad weather British households were suggesting that they were bunkering down for a very lean future.

The January release (not yet available) is being reported in the British media today. The UK Guardian article (early January 14, 2011) – Households plan to cut spending, Markit finance index shows – provides a summary of the Markit release (due later Monday GMT).

The article says that the survey found that British households were planning “to cut spending” because of :

… underlying fears of unemployment and the effects of the government’s public spending cuts …

The Guardian said that the “prospects for the economy worsened after a survey showed a sharp rise in the number of households who plan to restrict their spending over the next year”. A “record low number of households … [were] … planning to make large purchases over the next year”.

The survey is no surprise given all the related data that has come out in recent weeks which categorically show that the British economic growth has been slowing down again from the middle year.

In terms of the snow-storm defence, the Markit survey:

… appears to show a permanent downward trend with the optimism reported by households throughout the spring and summer of last year largely evaporating

The survey also notes that “high unemployment and fiscal tightening are dampening household demand and risk weakening economic growth”.

And over the water a bit …

I cannot not mention Ireland today given its political system is now in chaos as it should be given the appalling leadership that the government has provided in recent years.

The ABC news today is reporting that the – Irish government in tatters as Greens quit – which means the financial crisis then economic crisis then social crisis has rightly morphed into a political crisis and the fools who have led their nation backwards into bankruptcy are going to pay for their folly with their careers. Which is right!

The problem is that the choices for the Irish voters are stark. All major parties still support the passing of the controversial “Finance Bill” which is part of the IMF/EU bailout package and which imposes further harsh austerity measures on the country.

In terms of the upcoming national election whenever it is held the the two parties expected to form the winning coalition – Fine Gael and Labour both are supporting fiscal restraint.

There appears to be minimal differences between the two likely partners in macroeconomic terms. According to this story in the Irish Times:

The ratio of tax hikes to cuts is the only big issue where compromise will be needed post-election …

Fine Gael, historically fiscal conservatives favour heavy public spending cuts while Labour, pretending to be pro-Worker favour tax increases. Both agree on the need for a major retrenchment of the public sector.

Neither are advocating a Euro-exit and while they are posturing about minor changes to the bailout packages both will push it through now (in opposition) or later (in power). Once they lock that bill in then the chance to defend the country from harsh minimum wage cuts and other anti-poor measures will be lost.

The left supporters of the Labour Party may well desert it (lets hope so) and give Sinn Féin a boost. They are the only party resisting the neo-liberal ideology and have according to the Irish Times called “the Green Party’s intention to pass the Finance Bill, calling it a “travesty of democracy””. They want parliament immediately dissolved without passing the Finance Bill and leaving it to the people to determine whether the Bill passes.

Conclusion

Ireland has been cutting into public spending and private wages and conditions since early 2009. It has gone from bad to worse and will continue to decline in the coming quarters. It should be growing by now if the mainstream models were accurate.

And now … the second proponent of Ricardian Equivalence is giving us a laboratory for evaluating the theory – it fails again.

When will people stop listening to these defunct economists? When we will see mass resignations from economics departments on the basis of “we have nothing useful to offer anyone”?

That is enough for today!

Another whapping great flaw in the Ricardian argument is thus.

Deficits exist for two basic reasons. One is to bring stimulus: the classic Keynsian “borrow and spend” or “print money and spend” policy. A second reason for deficits is where government just fails to collect enough in tax to cover its spending: a so called “structural” deficit.

Most of the deficits in the West are accounted for by the structural factor. Now suppose a government wants to rectify the structural deficit, that in itself is no reason whatever to change its macroeconomic stance: it is no reason for extra (or less) stimulus. Thus rectifying a structural deficit (if it’s done properly) will NOT bring any change to household incomes. To that extent, households do NOT need to husband their resources to fund a future deficit reduction.

So my message to Ricardians is this: possibly the reason that the empirical evidence does not support your ideas is that the average household is smarter than the average academic economist who adheres to Ricardian ideas. Tee, hee.

But seriously, the idea that the average household is able to distinguish between the above mentioned structural and stimulus factors is TOTALLY AND COMPLETELY unrealistic. Only academics in ivory towers adhere to this sort of idea.

And yet there are constant calls for interest rate rises in the UK due to our ‘high’ CPI figures – 1.8% of which is tax rises.

Apparently the fear is that people will start asking for higher wages because they are paying higher prices at the pumps and in the supermarkets.

‘Advocates of a rise in interest rates are not “inflation nutters” but believe that believe that action is required to prevent an upward drift in inflationary expectations that would worsen the output-inflation trade-off, thereby depressing medium-term growth prospects.’ (Simon Ward from Henderson Global Investors)

So obviously if you increase interest rates and therefore put up the majority of working people’s mortgage bills, then they will obviously stop asking for more money.

It’s the logic of the madhouse surely.

Neil, madhouse is right. employees can ask for more money all they like, they wont get it. Employees will however make cutbacks in spending resulting in more unemployment. Feed Back Loops are very easy to understand, more should be made of FBL in the press so that some politicians may catch on.

I have noticed that the Policy industry is too willing to discuss stupidity like ” if governments cut their spending the private sector will fill the gap.”

Your average truck driver can see this is Bollocks (Balls or Bullshit). Why cant the Policy industry see it is BS and refuse to even start a discussion about it. A willingness to discuss this nonsense gets attention from some Politician and before you know it the unbelievably stupid idea has champions coming out of the woodwork.

Didn’t things have to get really bad for corporate profits before governments (and by extension, corporations) listened to Keynes? Since corporations and financial institutions have been bailed out of the great recession, maybe things aren’t bad enough for the governments to get the hint. And, as long as corporations remain in charge and their earnings increase, things may not change, no matter how much the people suffer. Even if the Irish change their government, won’t they just install more of the same. Look what happened in the US with the 2008 election- different people, same corporate policies!

Ralph,

Surely a ‘structural’ deficit is not the government ‘failing’ to collect enough tax, but simply that the transaction chain set in place by the government injection have ended up as net-private savings. In other words the non-government sector hasn’t spent enough to ensure that the injection disappears as taxation.

It would be just as accurate to say that the non-government sector has net-saved too much.

The business community is finally seeing sense …

…(or beginning to – barely – okay they’re not, but they are recognising the importance of aggregate demand).

The head of the CBI who originally supported the governments’ plans has decided that:

“The government has “taken a series of policy initiatives for political reasons, apparently careless of the damage they might do to business and to job creation”, Sir Richard said in his last major speech before his departure on Friday.”

See CBI Boss: Coallition Lacks Vision on the BBC website.

He actually pronounced the word “demand”! It is peculiar how the coallition (and indeed the previous government) had plans to cut / tax which were very directly going to affect aggregate demand. The previous governments plans were no better in that regard – increasing employees pension contributions is every bit as dangerous as this VAT hike.

Bill,

How do you respond to a common Liverpudlian who is struggling, but believes in austerity — and has replied in response to my posting some of your article in another discussion

Neil, I think my definition of “structural deficit” ties up with the common parlance definition. E.g. this Investor’s Chronicle article defines it as “the amount the government would borrow, if the economy were operating at its trend level”. By “trend level”, presumably they mean their idea of full employment level, which doubtless differs from Bill’s ideas on what constitutes full employment.

http://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/Columnists/ChrisDillow/article/20100215/1b8f8020-1a1e-11df-b0bd-0015171400aa/The-myth-of-the-structural-deficit.jsp

Plus there is a “This is Money” article which defines it as “the share of the budget deficit that would remain even after the economy recovers to its normal levels of output.” (Much the same as the Investor’s Chronicle definition.)

http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/30-second-guides/article.html?in_article_id=504739&in_page_id=53611#ixzz1ByDhhcqV

Your first sentence and a half suggest the structural deficit is the part of the deficit AIMED AT producing stimulus, but which fails to bring stimulus because households hoard the money. I would count that as part of the “stimulus deficit”.

I suspect that, “if you increase interest rates and therefore put up the majority of working people’s mortgage bills”, those executives getting 40% annual pay increases or bankers bonuses may not notice anything. They live in a purely theoretical world.

Rajiv, just explain to him how monetary system operates.

Link him to this video http://vimeo.com/6822294

Or this http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J0j5VwnD7I 😛

The belief that one will pay for current gov’t spending by future taxes is, for anyone over 30, irrational. It fails what Freud called reality testing. In the U. S. the Federal debt has been growing for 175 years. Anyone who has been around the block once or twice can’t help but notice the growth. 😉

UK GDP has shrunk by 0.5% in Q4 2010! Without the effect of the bad weather the ONS say that growth would have been 0%!Both the government and the opposition should be embarassed by this, but particularly the government.

First Ireland, then the UK, and then it will be the turn of Australia and the US for negative growth. Double-dip recession anyone?

Strangely Osbourne is not learning the lesson of this, and is saying (in terms of his austerity drive) that the “we should not be blown off course by the weather”. I would say that, though we cannot avoid the weather, we could at least stimulate demand and reintroduce Job Guarantee, so we can endure it more easily.

If David Ricardo would be alive today, he would have told the governments hoping for “expansionary fiscal consolidation” to not bet on the so-called “Ricardian consumers” to come and save the day! They are as real as the “homo economicus” many were believing in before the crisis. I have not met one Ricardian consumer in real life. Can the real Ricardians please stand up?

As a student of Miltom Friedman I remember him lecturing that assumptions are critical to building a hypothesis that is logical and consistent. Actually, he argued that economists who want to “win” an argument of analysis must first establish the assumptions of the debate, regardless if they are reasonable, which are neccessary to validate logically his hypothesis. “Lets assume…..perfect competition….”. The counterparty in the debate, whose hypothesis is based on different assumptions in order to be logically consistent and analytically invariant, can make the mistake of thinking that assumptions do not matter and foolishly accepts your assumptions for the sake of argument. Then the analysis from the debate concludes invariantly for the hypothesis consistent with the assumptions accepted unless sophistry is practiced, which is basically the art of interpreting reality with “empirical evidence” which is subject to the data collection/manipulation techniques and operations used.

Friedaman’s positive framework of analysis is flawed, not because he proposes assumption neutrality, but because he attempts to establish conditions that favor the assumptions of his ideology. He seeks to do so by interpreting the “chosen” empirical evidence that verifies the hypothesis that consistently and invariantly leads to the assumptions neccessary for his ideology.

Dear Takis, Brilliant. Friedman must have been a philosophy student as an undergrad and studied Plato’s dialogue, The Sophist. 🙂

Panayotis,

You were a student of Friedman ?

He seems to have known a lot of things. For example he was fully aware that central banks do not control the money supply, but tried to impose his theory on them when he became very powerful. He was also good at accounting. However he failed to understand that Monetarism can be a scourge. Maybe he knew that. 😉

You make good point about assumption neutrality. Apriori there is nothing wrong with it. People who study physical sciences are used to it and some make highly simplified assumptions to get powerful results in the first step and then learn about making the assumptions more realistic.

“He seeks to do so by interpreting the “chosen” empirical evidence that verifies the hypothesis that consistently and invariantly leads to the assumptions neccessary for his ideology.”

is an excellent point.

In fact Nicholas Kaldor accused him of being deliberately dishonest. … `makes it difficult to believe that in writing these elaborate yet worthless defences the authors were intellectually honest in the pursuit of the truth’