Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – September 7-8, 2019 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

If the external sector overall is in deficit, it is still possible for the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses and each pay down its debt as long as GDP growth is fast enough (the technical condition is that the rate of GDP growth has to be faster than the real interest rate).

The answer is False.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

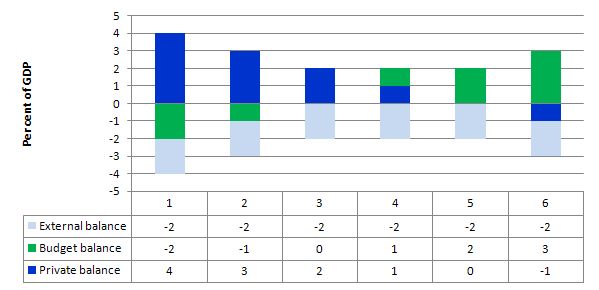

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns).

State 2 shows that when the fiscal surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced. State 3 is a fiscal balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the fiscal balance goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed fiscal balances into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough fiscal deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 2:

Federal government debt (where there is currency sovereignty) is not really a liability because the government can just roll it over continuously and thus they never have to pay it back. This is different to a household, which not only has to service its debt but also has to repay them at the due date.

The answer is False.

As a matter of clarification, it was assumed that it was debt issued in the currency of issue which is why I put the qualifier in brackets.

First, households do have to service their debts and repay them at some due date or risk default. The other crucial point is that households also have to forego some current consumption, use up savings or run down assets to service their debts and ultimately repay them.

Second, a sovereign government also has to service their debts and repay them at some due date or risk default. No different there. But, unlike a household it does not have to forego any current spending capacity (or privatise public assets) to accomplish these financial transactions.

But the public debt is a legal obligation on government and so is totally a liability.

Now can it just roll-it over continuously? Well the question was subtle because the government can always keep issuing new debt when the old issues mature and maintain a stable (or whatever). But as the previous debt-issued matures it is paid out as per the terms of the issue. So that nuance was designed to elicit specific thinking.

The other point is that the liability on a sovereign government is legally like all liabilities – enforceable in courts the risk associated with taking that liability on is zero which is very different to the risks attached to taking on private debt.

There is zero risk that a holder of a public bond instrument will not be paid principle and interest on time.

The other point to appreciate is that the original holder of the public debt might not be the final holder who is paid out. The market for public debt is the most liquid of all debt markets and trading in public debt instruments of all nations is conducted across all markets each hour of every day.

While I am most familiar with the Australian institutional structure, the following developments are not dissimilar to the way bond issuance (in primary markets) is organised elsewhere. You can access information about this from the Australian Office of Financial Management, which is a Treasury-related public body that manages all public debt issuance in Australia.

It conducts the primary market, which is the institutional machinery via which the government sells debt to the non-government sector. In a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates it is clear the government does not have to finance its spending so the fact that governments hang on to primary market issuance is largely ideological – fear of fiscal excesses rather than an intrinsic need. In this blog – Will we really pay higher interest rates? – I go into this period more fully and show that it was driven by the ideological calls for “fiscal discipline” and the growing influence of the credit rating agencies. Accordingly, all net spending had to be fully placed in the private market $-for-$. A purely voluntary constraint on the government and a waste of time.

A secondary market is where existing financial assets are traded by interested parties. So the financial assets enter the monetary system via the primary market and are then available for trading in the secondary. The same structure applies to private share issues for example. The company raises funds via the primary issuance process then its shares are traded in secondary markets.

Clearly secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders. In the context of public debt issuance – the transactions in the primary market are vertical (net financial assets are created or destroyed) and the secondary market transactions are all horizontal (no new financial assets are created). Please read my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more information.

Primary issues are conducted via auction tender systems and the Treasury determines the timing of these events in addition to the type and volumne of debt to be issued.

The issue is then be put out for tender and the market determines the final price of the bonds issued. Imagine a $A1000 bond is offered at a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $A50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $A1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations (see below). So for them the bond is unattractive unless the price is lower than $A1000. So tender system they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $A1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa. Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

So for new bond issues the AOFM receives the tenders from the bond market traders. These will be ranked in terms of price (and implied yields desired) and a quantity requested in $ millions. The AOFM (which is really just part of treasury) sometimes sells some bonds to the central bank (RBA) for their open market operations (at the weighted average yield of the final tender).

The AOFM will then issue the bonds in highest price bid order until it raises the revenue it seeks. So the first bidder with the highest price (lowest yield) gets what they want (as long as it doesn’t exhaust the whole tender, which is not likely). Then the second bidder (higher yield) and so on.

In this way, if demand for the tender is low, the final yields will be higher and vice versa. There are a lot of myths peddled in the financial press about this. Rising yields may indicate a rising sense of risk (mostly from future inflation although sovereign credit ratings will influence this). But they may also indicated a recovering economy where people are more confidence investing in commercial paper (for higher returns) and so they demand less of the “risk free” government paper.

So while there is no credit risk attached to holding public debt (that is, the holder knows they will receive the principle and interest that is specified on the issued debt instrument), there is still market risk which is related to movements in interest rates.

For government accounting purposes however the trading of the bonds once issued is of no consequence. They still retain the liability to pay the fixed coupon rate and the face value of the bond at the time of issue (not the market price).

The person/institution that sells the bond before maturity may gain or lose relative to their original purchase price but that is totally outside of the concern of the government.

Its liability is to pay the specified coupon rate at the time of issue and then the whole face value at the time of maturity.

There are complications to the primary sale process – some bonds sell at discounts which imply the coupon value. Further, there are arrangements between treasuries and central banks about the way in which public debt holdings are managed and accounted for. But these nuances do not alter the initial contention – public debt is a liability of the government in just the same way as private debt is a liability for those holders.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

The term “beggar-my-neighbour” strategy describes a situation where a nation pushes its excess supply onto its trading partners is more applicable to Germany than China in the current situation.

The answer is True.

Beggar-thy-neighbour policies are taken to mean that one nation explicitly follows a policy that will hurt another nation. The terminology is an artefact of the gold standard convertible currency era where deficit nations were disadvantaged because to manage the parity they had to use adjustments (contractions) in the domestic levels of activity (output and employment).

Chronic deficit ountries then had various ways of minimising the damage of the domestic contractio and shift aggregate demand away from imports toward domestically-producing substitution.

Various import substitution policies (tariffs or quotas) were common and often justified by the so-called infant industry argument, whereby protection was held out to be a medium-term strategy only while the nascent industry develop economies of scale and could compete in an open market. The problem (the topic of another blog) was that the “baby hardly ever grew up”.

Governments were reluctant to push domestic wage levels down during this period although the business sector was continually demanding they do just that – more to garner a higher profit share than for the external competitive reasons they used to justify their demands.

But it remained that chronic deficit countries during this period enjoyed slower real wage growth and so there was an element of austerity endured in that respect.

The other major policy open to governments under fixed exchange rate system was subject to IMF approval (post World War 2) a government could devalue (or revalue) – that is, change the fixed parity they had to defend. The slight flexibility in the monetary system led to what was known as competitive devaluations where a nation would devalue to its real exchange rate.

A series of competitive devaluations involving the UK and other nations in the 1965 as they struggled with domestic recession under the fixed-exchange rate system led ultimately to the collapse of the system in 1971.

So with that background the best answer is True.

When the EMU was established, the German government realising it had lost its exchange rate flexibility, as a vehicle to maintain external surpluses, embarked on an aggressive low-wage strategy to ensure the real exchange rate (the price level-adjusted nominal parity) was competitive and so they could continue to offer export prices that were more attractive that the other EMU nations. The so-called Hartz reforms were a central plank of this deflationary strategy.

More than 45 per cent of German exports are within the EMU. Exports to China, Japan, US, and the UK total about 22 per cent.

The Germans have always been obsessed with its export competitiveness and in the period before the common currency they would let the Deutschmark do the adjustment for them. With that capacity gone in the EMU arrangement, they pursued another strategy which was to deflate labour costs not via high productivity growth but rather by punitive labour market deregulation.

The Hartz reforms were the exemplar of the neo-liberal approach to labour market deregulation. The Hartz process was broadly inline with reforms that have been pursued in other industrialised countries, following the OECD’s job study in 1994; a focus on supply side measures and privatisation of public employment agencies to reduce unemployment. The underlying claim was that unemployment was a supply-side problem rather than a systemic failure of the economy to produce enough jobs.

The reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market (so-called mini/midi jobs) and there was a sharp fall in regular employment after the introduction of the Hartz reforms.

The way in which the Germans pursued the Hartz reforms not only meant that they were undermining the welfare of the other EMU nations but also drove the living standards of German workers down.

So while the Germans were busily exporting into the EMU they were also undermining the capacity of those nations to continue purchasing those exports. The crisis in Greece and other smaller EMU nations is an example of the costs those nations are bearing because of the fixed exchange rate characteristics of that monetary system.

They now have to adjust via domestic deflation to bring imports down and maintain funding for their net public spending.

Some will say that China by deliberately selling its own currency and buying US dollars to promote a trade surplus is also engaging in beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour. The rumour is that the Chinese currency is perhaps 20-50 per cent undervalued, depending on who you talk to. So the Chinese government is effect “devaluing” its currency to retain a competitive edge.

The reason this is not an example of beggar-thy-neighbour behaviour is because its principle trade competitors are not constrained by a fixed exchange rate themselves. For example, the US can use domestic policy freely to counteract the demand-draining effects of the external deficit should it want to. Under the fixed exchange rate system that was not possible to any large degree.

This is not to say that the consequences of the external relationship between say the US and China is not without issues and costs. But the US government is not facing the same policy impotence that the external deficit countries faced during the convertible currency period.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- China is not the problem

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

According to T.G. Congdon:

“25:26 there’s really a huge resource transfer

25:29 implicit in this diagram basically with

25:32 the current level of interest rates it’ll be

25:35 different if there were high ECB

25:37 charging higher normal interest rates

25:38 but it isn’t it’s basically no return

25:40 that Germans are receiving no returns on

25:43 about a trillion euros worth of foreign

25:46 assets and there is implicitly therefore

25:48 a massive resource transfer from Germany

25:54 and the other creditor countries to the

25:56 the borrowing countries”

It seems to me that the equations you wrote in answer to question 1 can be used to probe for fallacies in non-MMT economics. If the equations are true by definition and independent of context, then using data where such economic medicine is applied should show a divergence from the desired economic health. (I am not an economist, but an engineer, but what little i know of MMT makes sense to me).