Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – February 5, 2011 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

When a government such as the US government voluntarily constrains itself by issuing debt to match $-for-$ its net spending position (deficit), it reduces the funds available to the private sector for their own spending.

The answer is False.

It is clear that at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

However, the notion of opportunity cost relies on the assumption that all available resources are fully utilised.

Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

If the economy is already at full capacity, then a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

However, the question is focusing on the concept of financial crowding out which is a centrepiece of mainstream macroeconomics textbooks. This concept has nothing to do with “real crowding out” of the type noted in the opening paragraphs.

The financial crowding out assertion is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention. At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment.

The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Additionally, credit-worthy private borrowers can usually access credit from the banking system. Banks lend independent of their reserve position so government debt issuance does not impede this liquidity creation.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- When a huge pack of lies is barely enough

- Saturday Quiz – April 17, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion

Question 2:

When the national government’s budget balance moves into surplus:

(a) it is a sign that the government is trying to constrain economic activity.

(b) it is a sign that the government is worried that inflation is rising.

(c) you cannot conclude anything about the government’s policy intentions.

(d) Options (a) and (b).

The answer is that you cannot conclude anything about the government’s policy intentions.

The actual budget deficit outcome that is reported in the press and by Treasury departments is not a pure measure of the fiscal policy stance adopted by the government at any point in time. As a result, a straightforward interpretation of

Economists conceptualise the actual budget outcome as being the sum of two components: (a) a discretionary component – that is, the actual fiscal stance intended by the government; and (b) a cyclical component reflecting the sensitivity of certain fiscal items (tax revenue based on activity and welfare payments to name the most sensitive) to changes in the level of activity.

The former component is now called the “structural deficit” and the latter component is sometimes referred to as the automatic stabilisers.

The structural deficit thus conceptually reflects the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors.

The cyclical factors refer to the automatic stabilisers which operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the budget balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The problem is then how to determine whether the chosen discretionary fiscal stance is adding to demand (expansionary) or reducing demand (contractionary). It is a problem because a government could be run a contractionary policy by choice but the automatic stabilisers are so strong that the budget goes into deficit which might lead people to think the “government” is expanding the economy.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this ambiguity, economists decided to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the budget balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

As a result, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. As I have noted in previous blogs, the change in nomenclature here is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construction of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

This framework allowed economists to decompose the actual budget balance into (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical budget balances with these unseen budget components being adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

The difference between the actual budget outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical budget outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the budget balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the budget is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the budget into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The question then relates to how the “potential” or benchmark level of output is to be measured. The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry among the profession raising lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s.

As the neo-liberal resurgence gained traction in the 1970s and beyond and governments abandoned their commitment to full employment , the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

The estimated NAIRU (it is not observed) became the standard measure of full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then mainstream economists concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

Typically, the NAIRU estimates are much higher than any acceptable level of full employment and therefore full capacity. The change of the the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance was to avoid the connotations of the past where full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels.

Now you will only read about structural balances which are benchmarked using the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending because typically the estimated NAIRU always exceeds a reasonable (non-neo-liberal) definition of full employment.

So the estimates of structural deficits provided by all the international agencies and treasuries etc all conclude that the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is – that is, bias the representation of fiscal expansion upwards.

As a result, they systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

The only qualification is if the NAIRU measurement actually represented full employment. Then this source of bias would disappear.

Why all this matters is because, as an example, the Australian government thinks we are close to full employment now (according to Treasury NAIRU estimates) when there is 5.2 per cent unemployment and 7.5 per cent underemployment (and about 1.5 per cent of hidden unemployment). As a result of them thinking this, they consider the structural deficit estimates are indicating too much fiscal expansion is still in the system and so they are cutting back.

Whereas, if we computed the correct structural balance it is likely that the Federal budget deficit even though it expanded in both discretionary and cyclical terms during the crisis is still too contractionary.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

If the external balance remains in surplus, then the national government will not impede economic growth by running a budget surplus.

The answer is False.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

Thus, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and public surplus (G – T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process.

Second, you then have to appreciate the relative sizes of these balances to answer the question correctly.

Consider the following Table which depicts three cases – two that define a state of macroeconomic equilibrium (where aggregate demand equals income and firms have no incentive to change output) and one (Case 2) where the economy is in a disequilibrium state and income changes would occur.

Note that in the equilibrium cases, the (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M) whereas in the disequilibrium case (S – I) > (G – T) + (X – M) meaning that aggregate demand is falling and a spending gap is opening up. Firms respond to that gap by decreasing output and income and this brings about an adjustment in the balances until they are back in equality.

So in Case 1, assume that the private domestic sector desires to save 2 per cent of GDP overall (spend less than they earn) and the external sector is running a surplus equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

In that case, aggregate demand will be unchanged if the government runs a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP (noting a negative sign on the government balance means T > G).

In this situation, the surplus does not undermine economic growth because the injections into the spending stream (NX) are exactly offset by the leakages in the form of the private saving and the budget surplus. This is the Norwegian situation.

In Case 2, we hypothesise that the private domestic sector now wants to save 6 per cent of GDP and they translate this intention into action by cutting back consumption (and perhaps investment) spending.

Clearly, aggregate demand now falls by 4 per cent of GDP and if the government tried to maintain that surplus of 2 per cent of GDP, the spending gap would start driving GDP downwards.

The falling income would not only reduce the capacity of the private sector to save but would also push the budget balance towards deficit via the automatic stabilisers. It would also push the external surplus up as imports fell. Eventually the income adjustments would restore the balances but with lower GDP overall.

So Case 2 is a not a position of rest – or steady growth. It is one where the government sector (for a given net exports position) is undermining the changing intentions of the private sector to increase their overall saving.

In Case 3, you see the result of the government sector accommodating that rising desire to save by the private sector by running a deficit of 2 per cent of GDP.

So the injections into the spending stream are 4 per cent from NX and 2 per cent from the deficit which exactly offset the desire of the private sector to save 6 per cent of GDP. At that point, the system would be in rest.

This is a highly stylised example and you could tell a myriad of stories that would be different in description but none that could alter the basic point.

If the drain on spending outweighs the injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced).

So even though an external surplus is being run, the desired budget balance still depends on the saving desires of the private domestic sector. Under some situations, these desires could require a deficit even with an external surplus.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 4:

Fiscal rules such as are embodied in the Stability and Growth Pact of the EMU create conditions of slower growth because they deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary.

The answer is False.

The fiscal policy rules that were agreed in the Maastricht Treaty – budget deficits should not exceed 3 per cent of GDP and public debt should not exceed 60 per cent of GDP – clearly constrain EMU governments during periods when private spending (or net exports) are draining aggregate demand.

In those circumstances, if the private spending withdrawal is sufficiently severe, the automatic stabilisers alone will drive the budget deficit above the required limits. Pressure then is immediately placed on the national governments to introduce discretionary fiscal contractions to get the fiscal balance back within the limits.

Further, after an extended recession, the public debt ratios will almost always go beyond the allowable limits which places further pressure on the government to introduce an extended period of austerity to bring the ratio back within the limits. So the bias is towards slower growth overall.

It is also true that the fiscal rules clearly (and by design) “deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary”. But that wasn’t the question. The question was will these rules continually create conditions of slower growth. The answer is no they will not.

Imagine a situation where the nation has very strong net exports adding to aggregate demand which supports steady growth and full employment without any need for the government to approach the Maastricht thresholds. In this case, the fiscal rules are never binding unless something happens to exports.

The following is an example of this sort of nation. It will take a while for you to work through but it provides a good learning environment for understanding the basic expenditure-income model upon with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) builds its monetary insights. You might want to read this blog – Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output – to refresh your understanding of the sectoral balances.

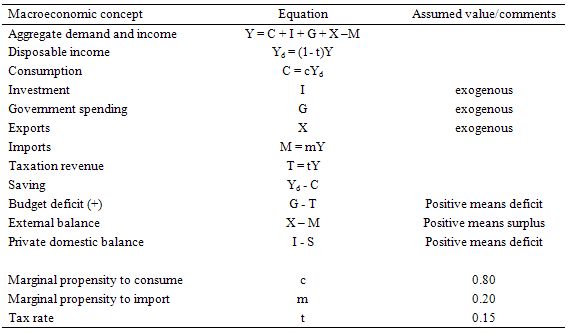

The following Table shows the structure of the simple macroeconomic model that is the foundation of the expenditure-income model. This sort of model is still taught in introductory macroeconomics courses before the students get diverted into the more nonsensical mainstream ideas. All the assumptions with respect to behavioural parameters are very standard. You can download the simple spreadsheet if you want to play around with the model yourselves.

The first Table shows the model structure and any behavioural assumptions used. By way of explanation:

- All flows are in real terms with the price level constant (set at whatever you want it to be). So we are assuming that there is capacity within the supply-side of the economy to respond in real terms when nominal demand (which also equals real demand) changes.

- We might assume that the economy is at full employment in period 1 and in a state of excess capacity of varying degrees in each of the subsequent periods.

- Fiscal policy dominates monetary policy and the latter is assumed unchanged throughout. The central bank sets the interest rate and it doesn’t move.

- The tax rate is 0.15 throughout – so for every dollar of national income earned 15 cents is taken out in tax.

- The marginal propensity to consume is 0.8 – so for every dollar of disposable income 80 cents is consumed and 20 cents is saved.

- The marginal propensity to import is 0.2 – so for every dollar of national income (Y) 20 cents is lost from the expenditure stream into imports.

You might want to right-click the images to bring them up into a separate window and the print them (on recycled paper) to make it easier to follow the evolution of this economy over the 10 periods shown.

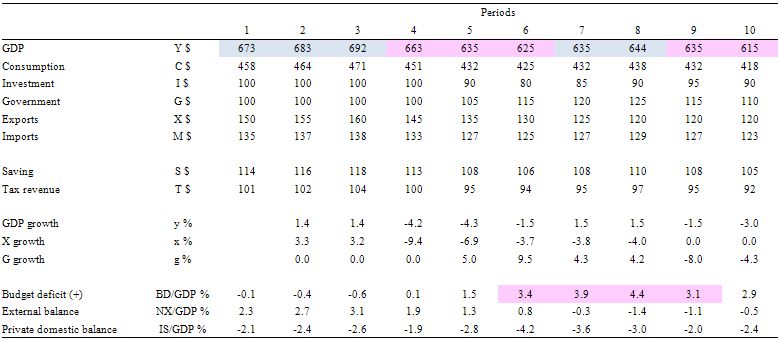

The next table quantifies the ten-period cycle and the graph below it presents the same information graphically for those who prefer pictures to numbers. The description of events is in between the table and the graph for those who do not want to print.

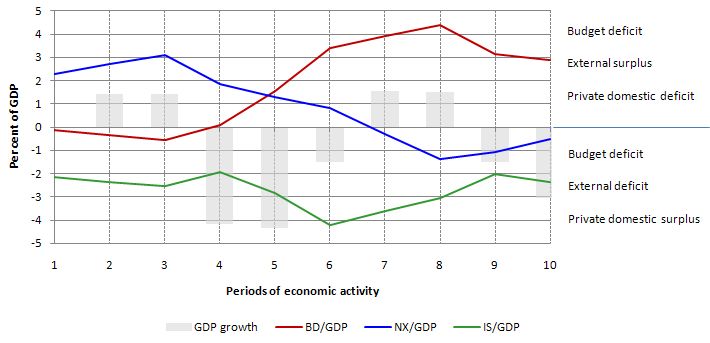

The graph below shows the sectoral balances – budget deficit (red line), external balance (blue line) and private domestic balance (green line) over the 10-period cycle as a percentage of GDP (Y) in addition to the period-by-period GDP growth (y) in percentage terms (grey bars).

Above the zero line means positive GDP growth, a budget deficit (G > T), an external surplus (X > M) and a private domestic deficit (I > S) and vice-versa for below the zero line.

This is an economy that is enjoying steady GDP growth (1.4 per cent) courtesy of a strong and growing export sector (surpluses in each of the first three periods). It is able to maintain strong growth via the export sector which permits a budget surplus (in each of the first three periods) and the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earning.

The budget parameters (and by implication the public debt ratio) is well within the Maastricht rules and not preventing strong (full employment growth) from occurring. You might say this is a downward bias but from in terms of an understanding of functional finance it just means that the government sector is achieving its goals (full employment) and presumably enough services and public infrastructure while being swamped with tax revenue as a result of the strong export sector.

Then in Period 4, there is a global recession and export markets deteriorate up and governments delay any fiscal stimulus. GDP growth plunges and the private domestic balance moves towards deficit. Total tax revenue falls and the budget deficit moves into balance all due to the automatic stabilisers. There has been no discretionary change in fiscal policy.

In Period 5, we see investment expectations turn sour as a reaction to the declining consumption from Period 4 and the lost export markets. Exports continue to decline and the external balance moves towards deficit (with some offset from the declining imports as a result of lost national income). Together GDP growth falls further and we have a technical recession (two consecutive periods of negative GDP growth).

With unemployment now rising (by implication) the government reacts by increasing government spending and the budget moves into deficit but still within the Maastricht rules. Taxation revenue continues to fall. So the increase in the deficit is partly due to the automatic stabilisers and partly because discretionary fiscal policy is now expanding.

Period 6, exports and investment spending decline further and the government now senses a crisis is on their hands and they accelerate government spending. This starts to reduce the negative GDP growth but pushes the deficit beyond the Maastricht limits of 3 per cent of GDP. Note the rising deficits allows for an improvement in the private domestic balance, although that is also due to the falling investment.

In Period 7, even though exports continue to decline (and the external balance moves into deficit), investors feel more confident given the economy is being supported by growth in the deficit which has arrested the recession. We see a return to positive GDP growth in this period and by implication rising employment, falling unemployment and better times. But the deficit is now well beyond the Maastricht rules and rising even further.

In Period 8, exports decline further but the domestic recovery is well under way supported by the stimulus package and improving investment. We now have an external deficit, rising budget deficit (4.4 per cent of GDP) and rising investment and consumption.

At this point the EMU bosses take over and tell the country that it has to implement an austerity package to get their fiscal parameters back inside the Maastricht rules. So in Period 9, even though investment continues to grow (on past expectations of continued growth in GDP) and the export rout is now stabilised, we see negative GDP growth as government spending is savaged to fit the austerity package agree with the EMU bosses. Net exports moves towards surplus because of the plunge in imports.

Finally, in period 10 the EMU bosses are happy in their warm cosy offices in Brussels or Frankfurt or wherever they have their secure, well-paid jobs because the budget deficit is now back inside the Maastricht rules (2.9 per cent of GDP). Pity about the economy – it is back in a technical recession (a double-dip).

Investment spending has now declined again courtesy of last period’s stimulus withdrawal, consumption is falling, government support of saving is in decline, and we would see employment growth falling and unemployment rising.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 5 – Premium question

In Year 1, the economy plunges into recession with nominal GDP growth falling to minus -1 per cent. The inflation rate is subdued at 1 per cent per annum. The outstanding public debt is equal to the value of the nominal GDP and the nominal interest rate is equal to 1 per cent (and this is the rate the government pays on all outstanding debt). The government’s budget balance net of interest payments goes into deficit equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP and the debt ratio rises by 3 per cent. In Year 2, the government stimulates the economy and pushes the primary budget deficit out to 2 per cent of GDP and in doing so stimulates aggregate demand and the economy records a 4 per cent nominal GDP growth rate. All other parameters are unchanged in Year 2. Under these circumstances, the public debt ratio will rise but by an amount less than the rise in the budget deficit because of the real growth in the economy.

The answer is False.

This question requires you to understand the key parameters and relationships that determine the dynamics of the public debt ratio. An understanding of these relationships allows you to debunk statements that are made by those who think fiscal austerity will allow a government to reduce its public debt ratio.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”.

Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, in mainstream (dream) land, the framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money.

This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Anyway, the mainstream claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

Neither proposition bears scrutiny – you can read these blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for further discussion on these points.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to “prove” that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the real GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate. Real GDP is the nominal GDP deflated by the inflation rate. So the real GDP growth rate is equal to the Nominal GDP growth minus the inflation rate.

This standard mainstream framework is used to highlight the dangers of running deficits. But even progressives (not me) use it in a perverse way to justify deficits in a downturn balanced by surpluses in the upturn.

The question notes that “some mainstream economists” claim that a ratio of 80 per cent is a dangerous threshold that should not be passed – this is the Reinhart and Rogoff story.

Many mainstream economists and a fair number of so-called progressive economists say that governments should as some point in the business cycle run primary surpluses (taxation revenue in excess of non-interest government spending) to start reducing the debt ratio back to “safe” territory.

Almost all the media commentators that you read on this topic take it for granted that the only way to reduce the public debt ratio is to run primary surpluses. That is what the whole “credible exit strategy” hoopla is about.

Further, there is no analytical definition ever provided of what safe is and fiscal rules such as those imposed on the Eurozone nations by the Stability and Growth Pact (a maximum public debt ratio of 60 per cent) are totally arbitrary and without any foundation at all. Just numbers plucked out of the air by those who do not understand the monetary system.

MMT does not tell us that a currency-issuing government running a deficit can never reduce the debt ratio. The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Here is why that is the case.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

The following Table simulates the two years in question. To make matters simple, assume a public debt ratio at the start of the Year 1 of 100 per cent (so B/Y(-1) = 1) which is equivalent to the statement that “outstanding public debt is equal to the value of the nominal GDP”.

Also the nominal interest rate is 1 per cent and the inflation rate is 1 per cent then the current real interest rate (r) is 0 per cent.

If the nominal GDP is growing at -1 per cent and there is an inflation rate of 1 per cent then real GDP is growing (g) at minus 2 per cent.

Under these conditions, the primary budget surplus would have to be equal to 2 per cent of GDP to stabilise the debt ratio (check it for yourself). So, the question suggests the primary budget deficit is actually 1 per cent of GDP we know by computation that the public debt ratio rises by 3 per cent.

The calculation (using the formula in the Table) is:

Change in B/Y = (0 – (-2))*1 + 1 = 3 per cent.

The data in Year 2 is given in the last column in the Table below. Note the public debt ratio has risen to 1.03 because of the rise from last year. You are told that the budget deficit doubles as per cent of GDP (to 2 per cent) and nominal GDP growth shoots up to 4 per cent which means real GDP growth (given the inflation rate) is equal to 3 per cent.

The corresponding calculation for the change in the public debt ratio is:

Change in B/Y = (0 – 3)*1.03 + 2 = -1.1 per cent.

So the growth in the economy is strong enough to reduce the public debt ratio even though the primary budget deficit has doubled.

It is a highly stylised example truncated into a two-period adjustment to demonstrate the point. In the real world, if the budget deficit is a large percentage of GDP then it might take some years to start reducing the public debt ratio as GDP growth ensures.

So even with an increasing (or unchanged) deficit, real GDP growth can reduce the public debt ratio, which is what has happened many times in past history following economic slowdowns.

Economists like Krugman and Mankiw argue that the government could (should) reduce the ratio by inflating it away. Noting that nominal GDP is the product of the price level (P) and real output (Y), the inflating story just increases the nominal value of output and so the denominator of the public debt ratio grows faster than the numerator.

But stimulating real growth (that is, in Y) is the other more constructive way of achieving the same relative adjustment in the denominator of the public debt ratio and its numerator.

But the best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio – which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.

Q5: “But the best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.”

Here’s where the rollover/cashout risk is. What if the entities holding the debt see that as an attempt to help the entity experiencing negative real earnings growth and don’t like that? They don’t rollover the debt and/or sell it so they can buy real assets to keep that negative earnings growth entity in that negative real earnings growth state.

IMO, the gov’t budget needs to be like the private entities’ budgets. The monthly payment/term is set up to pay off both interest and principal so that the demand deposits/debt are paid off at the end of the term.

Bill, I just have to give you a big “thank you” for your informative and insightful blog articles. They really are world changing. One thing that saddens me, however, is the knowledge that at present they only reach a tiny fraction of those who could benefit from them. Have you given any thought to how you could reach a wider audience? The world will owe you a huge debt if you can.

Alex;

Amen. But go and read Warren Mosler’s accounts of his personal interactions with the powerful and (allegedly) economically literate. (Larry Summers, Al Gore, Bob Rubin for example). These anecdotes can be found on Warren’s web site. What they consistently show is that even when these people can be convinced of some portion or element of MMT, they regard it as too heretical to repeat in public. So deeply are we propagandized in the Age of Friedman. It is too much to hope that full employment will be restored as a policy goal in the near term. We will not win this argument or avoid austerity. Austerity is here, and more is coming.

The most important constituency thus continues to be academia – we need to help “our” economists undermine and defeat “their” economists. This is the most we can hope for in Europe and America anyway. We need to keep the ideas of MMT in being until, in the words of Friedman himself, “the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.” This will not happen until Europeans and Americans have endured years more suffering and humiliation at the hands of the neoliberal hegemony. But it will happen, because those in power lack the power to end the crisis. When Americans have suffered as Egyptians have suffered, and been humiliated as Egyptians have been humiliated – only then will real change be possible.

This is, of course, on a relative sale. Our living standards will not fall to the garbage-sifting levels of Cairo or Manila. But in relative terms, we have the same problems: flat or declining incomes, rising unemployment and endemic government corruption. We will ultimately be required to resort to the same levels of sacrifice – and all the risks that accompany a popular revolt against a regime that is more violence-prone than it ever was, and with the ready-made pretext that any who resist are “on the side of the terrorists”.

So we should all keep studying our MMT and getting ready for the debate that will eventually come. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves. The corporate media will never willingly allow our side a fair hearing. And the mainstream stranglehold on the debate will not be relaxed on account of their continual failure in the real world. Those failures will continue and worsen. And events in the wider world – as with Tunisia and Egypt – will be less and less within the power of the Imperium to shape, much less control. Better days are coming, but they won’t come easily. Or soon.

Dale – agree that economists themselves are key to MMT gaining wider acceptance, but I’ve got to believe that there are short cuts. For example, it should be possible for some slightly heterodox publication like the New Yorker or the New Statesman in the UK to highlight/champion MMT – which would force the rest of the media to engage more. The issue here is that the media strongly prefers the narrative of govt debt = disaster.

I am impatient and trying to engage any economists I can on this stuff.

A key problem is that there does not exist any single page / document which summarises in the right level of detail. It’s always “you want to understand MMT? Spend a month reading Billy Blog” which simply isn’t going to get the ideas out.

I live in hope that one day one of the Profs Mitchell, Wray or Fullwiler will task some grad student to put all the key tenets and arguments on Wikipedia.

Damn your tricksy phrasing of questions!

I can’t agree with the answer of question 4. We know that when there is a recession (due to lack of aggregate demand etecera) it throws a significant proportion of the workforce out of work – and it takes much longer for those people to get back into the workforce than it does for GDP numbers to recover, and some may not ever make it back in. Those workers represent “slower growth”, continually, because they are not being “continually” used; their output is foregone, permanently, unless GDP growth coming out of the recession is so massively above trend that it can suck all the long-term-unemployed back into the workforce and make them so productive that they produce more than they would have if they were employed for the whole time. However, the budget deficits that would be necessary to produce this level of growth are precisely what Maastricht style rules would present.

I second Anders’ call for the relevant Wikipedia pages to be thoroughly expanded and updated.

Is the answer ‘false’ to question 4 a typo?

Dale,

Bear in mind that the Japanese have endured twenty years of the prevailing hedgemony. Yes they have a cultural disposition towards suffering, but still no change on the horizon.

Perhaps we should take the opposite approach and encourage the more ridiculous Austrian notions – which would hasten the destruction.

As my old dad says, if they won’t learn the easy way they’ll have to learn the hard way.

Jerry Cornelius, Q4 originally had the word “continually” in it, but it is not here. Does that help?

how about parallel institutions like MBA or MPA programs? i know that economists teach some of the classes for these degrees. Or CFA…