I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

Sometimes we get lost in detail and forget the simple macroeconomic relationships that sit below the complexity. I also like to get lost in detail too – to work out tricky little aspects of the financial system, etc but it is always a sobering experience to go right back to the beginning. I have been forcing myself to think “basic” lately as I progress the macroeconomics textbook that my mate Randy Wray and I are writing at present. It seems that our national governments have lost their perspective to think at this basic level – to really understand what drives prosperity in their nations. The evidence for this statement lies in the various fiscal austerity plans that are being rehearsed around the world at present. The most blatant and severe example of this in the non-EMU world has just been announced in Britain. This is a case of a government driven by ideology deliberately inflicting massive damage on its citizens while lying to the population about the necessity for such a policy. Its fits my definition of a state-motivated terrorist attack. If only the people of Britain understood the most basic economic relationship – aggregate demand drives output and national income. Cut spending and prosperity falls. Only by lying to the people, has the British government been able to take this policy path.

When I think about the British Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review I am reminded of Noam Chomsky’s Monthly Review interview in November 2001 entitled – The United States is a Leading Terrorist State where he said:

If you read the definition of low-intensity conflict in army manuals and compare it with official definitions of “terrorism” in army manuals, or the U.S. Code, you find they’re almost the same. Terrorism is the use of coercive means aimed at civilian populations in an effort to achieve political, religious, or other aims.

That is what the British government is engaged in at present.

The British government is claiming it is providing space for a private sector led-recovery based on a revival of consumption and investment spending aided and abetted by a surge in net exports. The basic hope is that private citizens and firms are Ricardian in nature. So apparently, consumers and investors are lying quietly with idle funds – saving them to pay for the higher taxes that would have been forced on them to pay for the rising budget deficits.

This pool of funds will allegedly burst into a spending frenzy once these citizens realise that the budget deficit will be lower as a result of the harsh fiscal cutbacks the Government has announced in the Comprehensive Spending Review and that they do not have to save to cover any higher tax burdens. That is the Ricardian world that the British government thinks it is operating in.

This is the mythical world that inhabits mainstream economics departments in universities around the world and the drivel that lecturers in macroeconomics feed their young students who would say boo and just sit there docile ingesting all the fairy tales. Please read my blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow – to see why the people are not Ricardian.

The predictions from these “Ricardian models” are regularly proven to be false in the world where real outcomes are determined. But my profession is blithe to that. Never let the facts get in the way of the theory. It is an appalling anti-intellectual approach.

Mainstream macroeconomics has virtually no content that is applicable to the real world. Yet a national government of an advanced nation of some 61.4 million people is prepared to introduce policies which will severely damage the life prospects of millions of these citizens based on these theories that are so thoroughly discredited. We have lost all sense of judgement in the last few years.

The reality is that the private sector is not spending at present because they are trying to restructure their precarious balance sheets after the credit binge that pushed growth along previously and because they are fearful that they might not have a job next week and/or that there will be no buyers queuing up to purchase the goods and services that might be produced.

Unemployment is a powerful deflationary force. The fiscal cutbacks will worsen unemployment and cause further conservatism among private spenders. Firms will revise their expectations of future sales downwards and lay off workers and consumers will further try to lift their savings ratio to provide some risk management in the case of a job loss. The probability of job loss will rise in the UK.

Further, I have heard people say that the large number of job cuts in the public sector will just clear out “unproductive labour”. Well, even if the workers being sacked were doing “nothing” each day – just sitting at their desks surfing the Internet or whatever – the loss to aggregate demand as their incomes vanish will be huge.

When was the last time, a checkout operator in a supermarket asked you whether you had a productive job or not as you handed over the cash to buy your weekly groceries? Answer: you have never been asked that! But the lost spending would cause the supermarket to contract, and as these impacts reverberated up the supply chain, further spending losses would occur and so it goes.

The British government has lost sight of the most basic understanding of macroeconomics and has instead listened to the shamans of my profession. The liars, the frauds who comprise the mainstream macroeconomists of the world.

There is a view that the Government knows full well what they are doing and are using it to advance ideological agendas. There is truth in that for sure. Either way, ignorance or malevolence – the implementation of the Comprehensive Spending Review is an act of state terrorism.

A few weeks ago I read a paper from the a researcher at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco entitled – Fiscal Spending Jobs Multipliers: Evidence from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – which estimates the employment impact of the fiscal stimulus in the US.

It is a fairly carefully constructed empirical study and concludes that:

The estimated jobs multiplier for total nonfarm employment is large and statistically significant for ARRA spending through March 2010, but falls considerably and is statistically insignificant beyond March. The implied number of jobs created or saved by the spending is about 2.0 million as of March, but drops to 0.8 million as of June. Across sectors, the estimated impact of ARRA spending on construction employment is especially large, implying a 23% increase in employment (as of June 2010) relative to what it would have been without the ARRA. Lastly, I find that spending on infrastructure and other general purposes has a large positive impact, while aid to state government to support Medicaid may actually reduce state and local government employment.

So again the evidence is clear – the fiscal expansion was a positive contributor to employment in the US.

What is also important to note is that the funds provided by the US government are still significantly unspent. You can track the spending trail at Recovery.gov by state using their GIS tool. The accompanying data shows that for the period February 17, 2009 to June 30, 2010 a total of $US218,206,202,543 was awarded but only $US85,703,541,778 was received by spending agencies. Even so, the total jobs dividend associated with the actual spending was 750,045.

They could have offered a minimum wage job to anyone and still not spend all the allocation.

The point is that the UK government is going against the obvious and using the lives and fortunes of their citizens as gambling chips in a casino where the punter will always lose. It is almost unbelievable how misguided the cuts are.

Back to basics

The following will be obvious for many of you but for the non-economists it might be a useful organising framework for understanding what is going on at the moment.

Sometimes we get lost in detail and forget the simple macroeconomic relationships that sit below the nuances. I also like to get lost in detail too – to work out tricky little aspects of the financial system, etc but it is always a sobering experience to go right back to the beginning. I have been forcing myself to think “basic” lately as I progress the macroeconomics textbook that my mate Randy Wray and I are writing at present.

So what drives output? What determines national income? What largely determines employment growth? What causes mass unemployment? These are much more important questions than having esoteric discussions about the pricing of some 3rd degree derivative that some engineer has contrived to fleece the clients of some hedge fund she/he is working for and redirect real output into the hands of the rich.

I am not saying that detailed discussions about financial markets, banking and whatever are not important but we tend to lose sight of what drives the big aggregates. The British government has clearly lost sight of what delivers wealth and prosperity in the UK.

Let us start at a most basic level. In this blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 I discuss the two-person economy. It doesn’t get much simpler than that. You might nominate yourself to be the government and your partner to be the non-government private sector to make it personal.

The government issues the currency in this two-person economy and the non-government offers labour (productive resources) in return for payments. Some product is created. We open a spreadsheet that records all transactions.

The government announces a tax of 100 dollars. The non-government person asks: “Where will I get the 100 dollars from to pay this tax?” The government says: “I will spend $100 on private sector activity which will provide the currency necessary to pay the taxes”. The relevant spreadsheet entries are made recording these transactions.

The column – budget balance in period 1 records a zero. The government runs a balanced budget (for example, spends 100 dollars and taxes 100 dollars). The private sector receives 100 and pays it back in taxes so has a zero balance at the end of the period. The private accumulation of fiat currency (savings) is thus zero in that period and the private budget is also balanced – they spend all they get and do not save.

Sit down with your partner at the table and type some numbers into the spreadsheet to see the entries appear and disappear electronically as the economy evolves – as the government injects spending and drains it via taxation. Watch what happens to the private saving column and compare it with the entry in the government budget each period.

Note clearly that the printer attached to the computer is silent – there is no “money” being printed.

What happens if the government spends 120 and taxes remain at 100? Answer: then private saving is 20 dollars and this can be accumulated as financial assets – initially in the form of numbers in the spreadsheet under private currency holdings. The government might call these holdings “private bank deposits” if it liked.

Where did the 20 dollars in savings come from? The additional net spending by the government to elicit further activity in the non-government sector provided the funds. The budget deficit for period 2 is 20 and this corresponds to the private saving in that period. A simple, ineluctable and pervasive result.

The government person might then say to the non-government person that they are prepared to encourage further saving and will issue an interest-bearing bond. So a column in the spreadsheet is created to record any “bond sales” which just amount to reducing a number in the “private bank deposits” column and putting that number into the bond sales column.

The government is not obliged to issue this bond. The net spending will still appear as before in the spreadsheet. The deficit does not need to be “financed” by borrowing. There is no operational imperative for the government to issue this debt as things stand. It is clear that the government is “borrowing” back what it has already spent.

Should the non-government person not wish to buy the bond (and earn the interest) they would just leave their savings in the “private bank deposit” column and presumably be happy about that. Nothing significant would arise from this decision. Yes, we could conduct elaborate analyses of bond prices, yields, secondary markets, etc but the essential insight is provided in this example. Nothing significant would happen to the level of activity in this economy if the bond was not issued.

The government deficit of 20 is exactly the private savings of 20 which may be stored in bonds or deposits. We could add any number of financial assets without contradicting the basic finding – over time, the accumulated private savings would equal the cumulative budget deficits.

Now what would happen if the government person decided to run a surplus (say spend 80 and tax 100)? Answer: in the next period the private sector person would owe the government a net tax payment of 20 dollars.

Where would they get that shortfall from? They would need to sell something back to the government to get the needed funds or run down their bank deposits. The result is the government generally buys back some bonds it had previously sold.

Either way accumulated private saving is reduced dollar-for-dollar when there is a government surplus. The government surplus has two negative effects for the private sector:

- The stock of financial assets (money or bonds) held by the private sector, which represents its wealth, falls; and

- Private disposable income also falls in line with the net taxation impost. Some may retort that government bond purchases provide the private wealth-holder with cash. That is true but the liquidation of wealth is driven by the shortage of cash in the private sector arising from tax demands exceeding income. The cash from the bond sales pays the government’s net tax bill. The result is exactly the same when expanding this example by allowing for private income generation and a banking sector.

From the example above, and further recognising that currency plus reserves (the monetary base) plus outstanding government securities constitutes net financial assets of the non-government sector, the fact that the non-government sector is dependent on the government to provide funds for both its desired net savings and payment of taxes to the government becomes a matter of accounting.

You will not find this basic understanding of the relationship between the government and non-government sector outlined in any of the mainstream macroeconomics books. Students do not learn the basic nature of the relationship – that from a national accounting perspective – a government surplus (deficit) has to be equal ($-for-$) with the non-government deficit (surplus).

If the non-government sector is to save overall then the government has to run deficits. There is no escaping that result. It is not my opinion or my prediction. It is the most basic macroeconomic fact that there is. If you don’t like it – get over it!

The British Government clearly doesn’t understand this basic fact. If it does, then its actions in cutting net public spending amounts to a malevolent deed and satisfies the conventional definition of a terrorist act.

So what drives output? What determines national income?

So what drives output? What determines national income? What largely determines employment growth? What causes mass unemployment?

Again we can be very simple in seeking answers to these questions.

In our two person economy the level of activity was determined by the government spending and the private sector was just paying taxes and saving. For the level of activity (employment of the private sector person) to remain constant and the private sector person to maintain a steady saving flow, the government had to maintain its deficit spending.

If we now think of a real world economy where the non-government sector is further decomposed in an external sector (where exports and imports are recorded) and a private domestic sector.

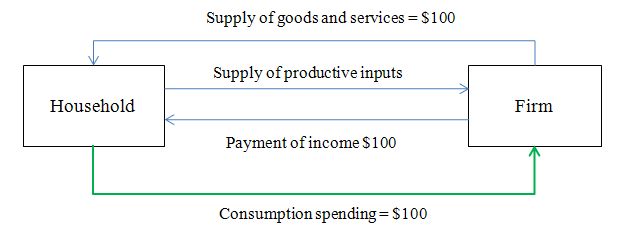

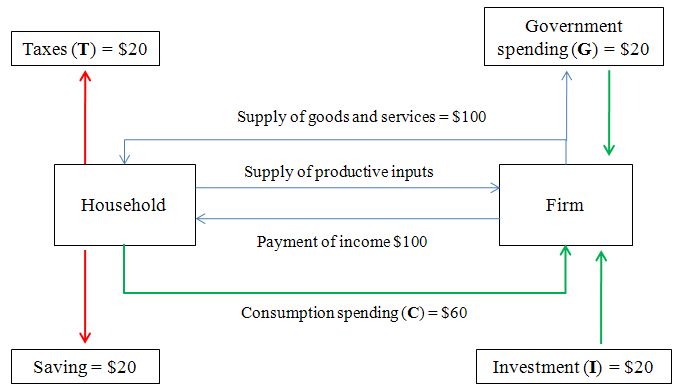

Starting out simply what if there was just a firm and a household and we abstract from government and the foreign sector.

The household provides productive resources to the firm which pays it an income. The firm in turns uses the productive resources to make goods and services which it sells to the household. The household can buy these goods and services with the income it receives from the sale of labour (or other productive inputs).

This sort of model is the basic macroeconomics circular flow model which is deficient overall because it abstracts from the basic government/non-government relationship but does offer some insights once you understand how net financial assets in the currency of issue enter the non-government sector (as explained in our simple two person economy above).

The following diagram is the most basic you can get in this context. It shows a steady-state where the business firms expect to sell $100 worth of goods and services each period and hire labour accordingly paying out $100 in national income. The households in turn spend all this income on consumption (the thick green line is the first component of aggregate demand in this economy) and do not save.

Each period, the expectations of the firms will be ratified by the spending decisions of the consumers and output and national income will remain unchanged.

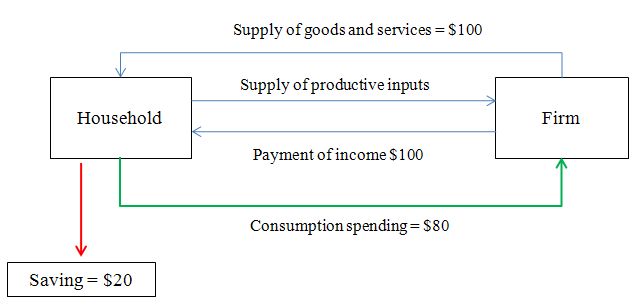

What would happen if the households decided to save? The following diagram captures that initial decision to withdraw consumption. Clearly, the circular flow is broken – and the firms would find they had $20 worth of output unsold. The national accountant would record this as unintended inventory accumulation which means that actual saving (S) would equal actual investment (I) but actual investment which is the sum of desired investment and unintended investment would be dominated by the unplanned inventory accumulation.

The normal inventory-cycle then would drive reductions in output and employment. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession. So in this example, unless there was an offsetting source of expenditure to fill the expenditure loss (gap) that is manifest as saving the economy would contract and income, consumption, saving all would fall until the actual level of saving equalled the desired investment level which in this case (so far) is zero.

We call saving a leakage from aggregate demand because it is taken out of the expenditure flow. Other things equal, a rise in a leakage will reduce output and national income.

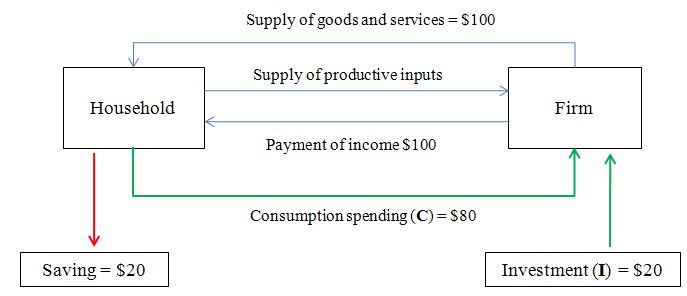

So the only way this economy can remain at its previous level of activity is if there is new source of expenditure to match the withdrawal of consumption. The following diagram shows that this could be accomplished by an injection of desired investment of $20. We call this “exogenous” investment (that is, derived from outside the circular flow) an injection.

Income adjustments will always ensure that the sum total of the injections will always equal the sum total of the leakages. That is the basic expenditure-output relationship that the British government is ignoring or choosing to ignore.

So the following diagram shows the injection of desired investment. There would be no unintended investment (unwanted accumulations of inventory) and actual saving ($20) would equal desired investment ($20) and the firms would be selling all they desired (and expected to sell). National income would remain at $100 comprising consumption (C) = $80 plus investment (I) = $20.

We would write total aggregate demand as:

Y = C + I

Now what if the government decided to raise taxes (say 20 cents in the dollar) which means at the current national income level it would seek revenue of $20 (for simplicity, all in the form of household taxes). The following diagram shows, first, the taxes (T) of $20 draining the household’s capacity to spend (reducing disposable income) and then the corresponding government spending (G) of $20 restoring the aggregate demand. Now we have the total supply of goods and services being divided between households and government.

The taxation is a leakage (drain) from aggregate demand while the government spending is an injection to the spending stream. Unless the government injected the $20, then the economy would begin to contract in the same way that the saving leakage would have forced a contraction in the earlier simple model.

You might also get confused here and ask – well the government sector is running a balanced budget yet the households are saving – so how does that square with the previous claim that government surplus (deficit) has to equal the non-government deficit (surplus)? The answer lies in realising that the non-government sector is the sum of the firms and the households and while the households are saving the firms are dis-saving an equal amount via investment. So overall, the balanced budget is not providing the scope for any net saving in the non-government sector.

So our aggregate demand model (the thick green lines) is now more complicated:

Y = C + I + G.

The uses of national income are as follows:

Y = C + S + T

So we can bring those two concepts of national income (sources and uses) together to get the sectoral balances in this two sector (government and private domestic) economy:

C + I + G = C + S + T

Or:

(S – I) = (G – T)

which tells you the private domestic balance (S – I) is indeed equal to the budget deficit (G – T) and income adjustments will ensure that is always the case.

The other point to note is that the leakages (red line flows) are always equal to the injections (green line flows) via income adjustments.

S + T = I + G

What would happen if we introduced a foreign sector? The same logic would apply. The following diagram shows a stylised example. Households (assumed to be the only purchasers of imports for simplicity) now by $10 on imports (M) which represents a leakage or drain from aggregate demand. If there was not a corresponding injection of aggregate demand then the economy would contract. In this case I have allowed the injection to be in the form of exports (X) to match the imports. The firms can thus sell all they plan either to households (C), the government (G) or to foreigners (X).

Aggregate demand (the thick green lines) is now:

Y = C + I + G + X – M

The uses of national income are as follows:

Y = C + S + T + M

So we can bring those two concepts of national income (sources and uses) together to get the sectoral balances in this two sector (government and private domestic) economy:

C + I + G + X = C + S + T + M

Or:

(G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M)

which is the familiar three-sector economy sectoral balances model. The way I have written this is to verify that the budget deficit (G – T) is always equal to the non-government surplus and vice versa, where the former is the sum of the private domestic balance (S – I) and the external balance (X – M).

In this stylised example, all the balances are zero whereas in the real world that is not found. I will come back to that next.

But also note, that the sum of the leakages (red line flows) are still always equal to the sum of the injections (green line flows) via income adjustments.

S + T + M = I + G + X

Analysis

To apply this understanding we need to introduce some real world parameters. Most nations run external deficits (X – M < 0) which means that there is a net drain on aggregate demand coming from the external sector. If there is not a corresponding adjustment in the other balances (to fill the spending gap) then aggregate demand would fall and national income would decline.

The income adjustments would ensure that at least one other balance (government budget or private domestic balance) went into an equal deficit.

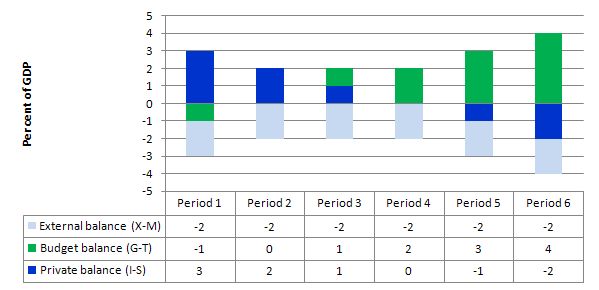

The following graph with an accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall) to show what the changes to the other balances mean for each other.

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X – M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), and if the government was able to run a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP this would mean the private sector would be in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

If the private sector resisted the need to “finance” that deficit by increasing indebtedness, then national income would contract and the government would be unable to run the surplus (as the automatic stabilisers would force taxation revenue to decline).

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terrorists typically overlook. If there is an external deficit and the government pursues a balance budget strategy (and succeeds) then the private domestic sector has to be running a deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt. That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit.

A balanced budget rule could never be a viable fiscal rule for an economy running an external deficit because it would force the private domestic sector into increased indebtedness if national income was to remain unchanged. Ultimately, the private sector would resist the increased precariousness of its balance sheet and attempt to save overall. At that point the income adjustments that would result would force the budget into deficit at much higher levels of unemployment.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

In yesterday’s blog – Why budget deficits drive private profit – you also learned that under these conditions, the government deficit would be stimulating private sector profits.

So what is the economics of this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is taking out in the form of taxes and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

So you see what is likely to happen in Britain

All of this is basic macroeconomic reasoning. Output and income growth is driven by aggregate demand. You can get as complicated as you like but that basic result remains. There are no other sources of national income.

So if the government aims to achieve a surplus (or reduce its deficit) and net exports remains negative then the only source of growth is a rising private domestic deficit (or reduction in its overall saving).

The other source of growth could be a sudden reversal of the external situation and thus a positive net contribution from the external sector.

Neither “new” source of aggregate demand is likely to emerge in Britain.

Households and firms are unlikely to start expanding their spending given that unemployment remains high and is likely to rise as the planned job cuts begin. The deflationary impact of the fiscal austerity will spread throughout the expenditure system and further discourage injections from private investment and or a decline in household saving.

All the likely private sector reactions are in the opposite direction – more desired household saving and less investment.

Further, net exports are unlikely to go into a large enough surplus given that world markets are now faltering. Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

Once you realise that mass unemployment is caused by a failure of aggregate demand then you will appreciate that the British government is orchestrating what is likely to be a significant rise in unemployment as a result of the planned direct public sector job losses and the multiplied job losses in the private sector that will follow the spending collapse.

Please read my blogs – What causes mass unemployment? and Unemployment is about a lack of jobs – for more discussion on this point.

The exact opposite policy remedy is required in the UK.

Budget deficits build productive infrastructure which exerts a positive influence on economic growth. Budget deficits typically help stimulate private investment because they keep aggregate demand from plummeting. So net public spending “crowds in” private spending because expectations of future demand are improved.

Budget deficits also “finance” the private sector’s desire to save because they stimulate national income growth.

Conclusion

If you withdraw spending from an economy and there is no likelihood that it will be replaced from one of the other known sources of spending then aggregate demand will decline. The economy will adjust to that spending cut by contracting output and employment. The initial losses will reverberate throughout the supply chain and spread beyond that into the wider economy as lost incomes lead to further losses of spending.

There is not magic solution but to restore aggregate demand.

In the UK as in most nations at present, the major component of growth is net public spending. Cutting that at this point is madness.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow with some easy questions and one more difficult (premium) question to head of the boasters out there who think they are on top of all of this! (-:

That is enough for today!

We call saving a leakage from aggregate demand because it is taken out of the expenditure flow. Other things equal, a rise in a leakage will reduce output and national income. So the only way this economy can remain at its previous level of activity is if there is new source of expenditure to match the withdrawal of consumption.

And this is why Say’s law (whether in the form of Say’s equality or Say’s Identity) will not necessarily work in the short or long run?

I have been reading Paul Davidson (Financial Markets, Money, and the Real World, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2002) and he argues that yet another “leakage” is when money gets tied up through speculation on financial assets on secondary markets (in a cycle of (1) money used to buy a financial asset then (2) the money given to a new speculator who holds it ready for a new financial asset purchase, then back to (1) and so on).

Do you think this is a fair view?

The one ‘good’ thing out of our government’s desire to decimate the economy is that it will provide hard evidence of the effects of the policies – mush as the 1920s and 30s did for Keynes et al.

It may be that the UK has to go through this for the greater good.

Does it make any difference if a household wants to consume an extra $20 worth of local food and services by borrowing $20 from a Japan?

It’s much easier to understand with the diagrams.

What are the chances of this being taught in Eton?

wow my attention span is far to short.

“Mainstream macroeconomics has virtually no content that is applicable to the real world.”

now where have i read something like that before?

Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live…

Just a minor point; I feel it’s unfair to Ricardo to call these models “Ricardian” – Ricardo himself said “but the people who paid the taxes never so estimate them, and therefore do not manage their private affairs accordingly.” he only put it forward as a thought experiment in a true gold-standard economy. These are “Barrovian” models.

A true Ricardian would heavily tax land speculators, miners and the idle rich, seek to lower the cost of living for the poor, and believes in some version of the labour theory of value.

Arthur!!!

Good to see you commenting over here!

Stick around for a while, check out somer older posts, get familiar with the commenters and start asking some questions. You will definitely learn something.

Theres no better place to start your day than at billy blog.

Thanks bill for a superbly informative blog!

I have a simple question – if private investment is greater than private saving (I>S), is that equivalent to saying the nation has foreign debt? Or does it depend on how much of that investment is excess stock (unintended investment) as opposed to desired investment?

I have enjoyed reading your blog for around a month now. For an economic layman like me what you say makes sense. Just to ask is the main point in your argument not already conceptualised as the paradox of thrift?

Equally I undertstand from reading your blog that the logical assumption for an efficient economy is full spending and no saving. This is an issue that detracts from solely economics as coming into my old area of study you can never trust all other independent actors not to save and gain themselves a competitive advantage at your loss. Hence why the best outcome for all is to save.

Please correct me if I am wrong.

James: Just a minor point

I disagree that this is a minor point, and I am happy to see the historical record set straight. There is too much misrepresentation of past thinkers owing to ignorance. As even many mainstream economists, such as Krugman and DeLong, have observed, most of the mainstream is woefully ignorant of economic history. So thanks for setting this straight and giving Ricardo his due. Please keep it up. We shouldn’t fall into their loose talk and sloppy thinking. It’s all too easy to fall prey to repeating their buzz words.

“Most nations run external deficits”

But the fewer countries that have surplus must in principle have the same total amount as the deficit countries have. In pricipe that is because there are anomalies in the number countries claim to have, it doesn’t add up to zero.

Hi, Bill-

“Note clearly that the printer attached to the computer is silent – there is no “money” being printed.”

Ah- very droll! Yet above, you write:

“The government issues the currency in this two-person economy…”

“The government says: “I will spend $100 on private sector activity which will provide the currency…”

There is no reason for all this currency to not be printed out and instantiated as tokens to be handed back and forth. It is simply out of post-modern convenience that you have chosen to use a spreadsheet instead, which in the event of a power outage may allow this economy to collapse ignominiously.

So I think the point stands that the “printing money” metaphor is perfectly applicable. Not only that, but people know in their bones that the government *does* print the money, which puts the lie to all the mainstream propaganda about private industry being the source of all money/wealth and the government having to steal it from the private sector, etc.

Burk, two things get confused by the public in the use of the term “printing money.” In a very obvious and trivial sense, bank notes are printed pieces of paper. In the non-trivial sense, “printing money” as ordinarily used signifies the cb increasing reserves, e.g., through QE, adding to the money base.

In the first place, reserves never enter the economy and get spent. They are just number on accounts, either in ink as previously, or digitally as now. The connection between the notes and reserves is that banks exchange reserves in their account that the cb for notes, which they hold as vault cash in anticipation of customer demand. Customers draw down their account in exchange for notes.

Secondly, the cb is just shifting the composition of assets. Reserves are its liability, and like on other balance sheets the liabilities are offset by assets. (Unlike other liabilities, the government’s liabilities are irredeemable under a nonconvertible floating rate system.) When the cb buys bonds, it takes the bonds on its balance sheet and reserves increase in the sellers account. Since the bonds were initially exchanged for reserves, this is just a shift back in aggregate. No new financial assets created.

The public confuses reserve operation with printing of notes for circulation. There is no intrinsic connection. As far as MMT is concerned, the term “printing money” is a canard.

“So I think the point stands that the “printing money” metaphor is perfectly applicable.”

No they don’t print money. They spend it. It is that which adds benefit to the economy as long as it is not to excess.

“- aggregate demand drives output and national income. Cut spending and prosperity falls.”

Aggregate demand and Government spending are not the same. Yet from one sentence to the next, you attempt a switch-a-roo on us. Cuts in *government* spending to not necessarily cause a reduction in prosperity. You are the one lying, as I doubt you are confused about this.

You gotta love Warren Mosler.

“Senate Candidate Bets Congress $100 Million That the U.S. Government Cannot Run out of Money”

http://moslereconomics.com/2010/10/22/press-release-3/

Dear Richard (at 2010/10/23 at 7:34)

You noted:

I suggest you go back to the first few weeks of Macroeconomics 101 – Mainstream or otherwise. The fact that government spending adds to aggregate demand is not controversial in any paradigm whereas the net effects of this addition might be debatable.

Aggregate demand is the sum of total spending – household consumption, private investment, net exports and government spending.

The mainstream argue clearly that government spending crowds out private spending. But they acknowledge it is still aggregate demand! Your further point that “Cuts in *government* spending to not necessarily cause a reduction in prosperity” is true and I agree with you and have never said otherwise. Not necessarily is the operative qualification. The point I made in this blog which you seem to want to ignore for the sake of accusing me of lying is that cuts in government spending which are not replaced by an equal rise in private spending will cause a reduction in prosperity. Every professional economist agrees with that point if there is idle capacity. Sorry.

I would also note that I deleted another of your comments (2010/10/23 at 7:52) where you claim I said something when in fact it was a quotation from someone else and I provided that quote in a different post to the one you attempt to comment on. Then followed a one line personal attack on me rather than my ideas without further substantiation, argument or evidence. I remind you that I have a Comments Policy and that your attack was in violation of that policy.

I may be wrong and I welcome informed commentary pointing that out or adding other interesting points to the edification of all of us. But to accuse me of being a paranoid liar without further evidence or discussion is not edifying at all and will never be published on my blog. I don’t see the point in rehearsing unsubstantiated bile here.

I may be a paranoid liar and would like to know how you conclude that so I can get help if you are correct. Why not provide some argument to support your view and we will see where we go with that?

best wishes

bill

“Aggregate demand is the sum of total spending – household consumption, private investment, net exports and government spending.”

Of course. Feel free to tell your readers that if the government starts using paper currency as toilet paper, AD has increased.

You know precisely how gov’t spending as a component of AD can be misleading, and you’ve put it to good use here. Yes, if you just want AD to increase, triple the president’s salary. Better yet, triple the military expenditures. The more tanks we have, the more prosperous we are. It’s Econ 101. Interest paid on debts increases AD.

Tell your readers how starting a war increases AD and–this will be the best part– how that translates into prosperity. If AD causes prosperity, why has Foreign Aid failed so miserably?

If government spending causes prosperity, why not just keep on spending indefinitely?

Our blog author has confused actual prosperity with a number, a redistribution as an increase. If the government stops spending, yes, AD drops (as data), but there’s not a dimes worth of difference in the actual prosperity of the nation.

Answer this: Does the U.S. have more prosperity because of the AD increases caused by wars in Iraq and Afghanistan? Keynesian economics in one simple lesson: Invade thy neighbor.

“cuts in government spending which are not replaced by an equal rise in private spending will cause a reduction in prosperity.”–You So, if the U.S. were to stop all of it’s spending in Iraq–with no increase in consumer spending–it would be less prosperous?

Dear Bill,

Thanks so much for the occasional explanation like this: God I’d love to see you on the 7:30 Report instead of ‘Mr pontification’. Cheers …

jrbarch

I have refined my question, anyone help with an answer? I am refering to Bill’s diagram 2.

Does it make any difference if a household wants to consume an extra $20 worth of local food and services by borrowing $20 from an Overseas bank? What if the $20 is used to buy a house?

So I figured this out> the 20$ just goes round and round until its repaid to the Overseas lender. While its going round and round its getting taxed out of existence isn’t it? It keeps going round and round until one day the Overseas Lender wants its $20 back? So the 20$ firstly added to job creation then detracts from it in some future year when it is repaid?

I only want an answer because I read that Australian Banks borrow from Overseas about 30% of every dollar they lend with a lot of it going into Residential Mortgages. I couldn’t figure out if this is good or bad for jobs long term. I don’t care how rich or crowded with stuff peoples homes get as long as everyone has a right to a job, income for a good life, shelter and health care. if MMT can deliver it I will support it.

Richard, this site has always being very tolerant of stupid questions but it is not tolerant of rude personal attacks. Bill is equal to anything you can dish out anyway.

Nice small waves again this morning in warm water too. ps have found spellchecker. It wont fix my grammer though.

bill, I think you need to add a medium of exchange supply. I also believe you need to add a “firm” that is bank or bank-like. That means someone saves $20 and that $20 is invested as bank capital that becomes $200 in debt (demand deposit medium of exchange).

Punchy said: “Does it make any difference if a household wants to consume an extra $20 worth of local food and services by borrowing $20 from an Overseas bank? What if the $20 is used to buy a house?”

And, “I only want an answer because I read that Australian Banks borrow from Overseas about 30% of every dollar they lend with a lot of it going into Residential Mortgages.”

Those two seem different to me. Can you expand on the second part?

Hi Bill

I’ve got a mental block on ‘I’

I can see the consequences of savings on inventories.

Are you (or the National Accountant) saying that ‘I’ is always a balancing figure for the Sources NI equation that can be assumed to be restocking or destocking of inventories? Or is the ‘Private Investment’ coming from elsewhere?

After a bit more consideration..

Is ‘I’ effectively a combination of previous period’s savings on things that don’t get consumed in the current period and the change in inventories in the current period?

Hi Fedup,

your right I have confused my own question, Thanks. Is it the case that if I borrow from O/S and spend it in my country it does little or nothing for the country where the money came from but will create employment in my country. When I pay the money back to the O/S lender will it cost jobs in my country?

As for Australian banks borrowing from O/S so we can pay more and more for Houses (shelter) I just cant see how it adds anything at the Australian end of the deal. I wanted to know what it adds as we are doing plenty of it.

Cheers Punchy

I know I’m late to the party, but there is a chance someone will answer my question.

Tom Hickey said, “reserves never enter the economy and get spent.” My question is if that means that QU isn’t being used by the big banks to raise stock prices. Also, is the Fed really allowed to spend money in the market. I asked because at some sites I visit I read all kinds of things about what is done with QU and what the Fed does.

Also, the banks have been accused of simply buying Treasuries and getting the interest. My understanding is that the Fed buys up the excess reserves and pays the discount price for them. Is that correct and if so does that mean excess reserves can’t be used to buy Treasuries?

I also have a question about the austerity in Britain. I know that in the US private debt to GDP is around 270% ( which I realize is unsustainable and decreasing), but I’m wondering if the Brit’s have a low enough private debt to GDP ratio to help delay the ill effects of austerity for any length of time- like maybe until more reasonable heads take control.

In QE, banks are selling mortgage backed securities (MBS) to the Fed in return for reserves. The excess reserves earn 0.25% from the Fed. This positive interest rate policy was originally done to ensure liquidity in the payments system, as reserves are the final accepted form of settlement.

Banks may or may not be using those reserves to buy up Treasuries – but it is basically a swap of assets between Treasuries and reserves. Short-term treasuries (1 mo/3 mo/6 mo) are 0.15%/0.16%/0.19%, so the banks do better just leaving the reserves sit.

This is not an injection of funds into the system, it is a swap of longer term assets (MBS) that have higher interest rates for shorter term assets (reserves) with lower interest rates. This will tend to drop the long term interest rates (by the market showing a preference for low risk, low interest assets). Because the Fed is buying up MBS assets (assume at a higher price than the market, otherwise they would let the market do it), this has the effect of raising or at least slowing the decline in these asset prices.

The effects on income of this policy is unclear – borrowing costs should decrease long term, but interest income is also decreasing. Since the wealthy are continuing to increase their share of the current income stream, the decline in interest income is less important to them than to the fixed income folks who depend on interest payments. But, again, the future effects of this policy are unclear.

I am not sure, but banks may be able to use their increased reserve position to increase their leverage in other markets (e.g., equities), especially since commercial and investments banks are combined into single entities. But I do not know if there are regulatory controls to manage such actions. At a minimum, the repair to their balance sheets have allowed them capacity to increase leverage in other markets, driving up asset prices.

@GLH

I’ve some bad news. The UK privat sector is deep in the hole. The government is virtuous compared to it even by mainstream economic reasoning. McKinsey: Overall UK debt: 469% of GDP. Composition: Government: 52%; Nonfinancial Business: 114%; Households: 101%; Financial Institutions: 202% (reflects that London is a financial hub). Something must be wrong with British education standards? They seem to have serious trouble with arithmetics?

I have finally solved my ‘I’ problem.

The problem was that the NI accounting identities were not holding true in the spreadsheet I was building because I was applying G & T transactions to firms whereas I believe they should have been confined to households.

Anyway all the identities now match and the ‘I’ accounting adjustment seems to me to be an important concept. The direct correlation between firms and household savings is clear and I can see how ‘I’ not only holds up aggregate demand and puts money in households savings, as well as providing scope for increased future output, it is also the signal (from household savings) to firms to change their behavior with regard to jobs and output.

The importance of the appropriate fiscal policy become even clearer to me.

Thanks for the refresher Bill. I look forward to the textbook.

Thanks to both pebird and Stephan.

I was just over at Krugman’s blog on QE2, and perusing some of the comments, people are hopelessly confused on what reserves are. Krugman himself confuses the matter in his post by calling them short term government “borrowing.” However, reserves are neither current liabilities nor payables at all in the ordinary sense of nongovernment accounting. As I believe Stiglitz observes, reserves are not redeemable.

Krugman correctly includes reserves and currency in the monetary base as the Fed’s liabilities. Currency is exchangeable at face value for reserves by banks belonging to the FRS. It should be obvious that currency is not redeemable either.

Then Krugman goes even further down this hole by called these putative current liabilities “debt.” No wonder people are confused.

Tom,

I think there’s more right than wrong in Krugman’s post. The main issue is that QE is a duration swap and Krugman at least got that right – which is a lot actually. Go over to the monetarist sites if you can stomach it and they’ll be talking about QE and the multiplier.

You’re right if you want more precision than that, but the issues do become semantic. I can see where you’d be sensitive to the use of the terms “borrowing” or “debt” in the context of MMT.

The issue of redeemability also is not immune from semantics considerations. You could always say that reserves and currency are redeemable for tax credits – i.e. the elimination of tax liabilities – an interpretation that is MMT aware as well.

Neil Wilson says:

Friday, October 22, 2010 at 19:31

Maybe some do need the UK to go through this in order to learn.

However, those about to be thrown out into the street would disagree with the need to reinvent the wheel. It’s too cold here and those who need to learn will be warmed at home, in government offices etc!

Billy is right to use the word ‘terrorism’. Because those inflicting this will not suffer.

JKH: I can see where you’d be sensitive to the use of the terms “borrowing” or “debt” in the context of MMT.

I am not quibbling with Krugman on the correctness of what he is saying. I am just focusing on the terminology that reinforces the notion that government finance is analogous to nongovernment finance. I’m sure that Krugman is just using the terms conventionally, but reading the comments to his post is clear that ordinary people pick up the wrong idea. The reason we have operational definitions is to be precise and obviate confusion.

You could always say that reserves and currency are redeemable for tax credits – i.e. the elimination of tax liabilities – an interpretation that is MMT aware as well.

Yes, but if one calls reserves and currency government “debt,” then to be consistent one should say correspondingly that tax obligations are “debts” to government, and the person is the street is going to say, “But I never borrowed anything from government.” 🙂

People who understand what going on aren’t taken in by the terminology, but ordinary people are, and it perpetuates the myths.

Helen @ 10:57

In Economics as Religion, Robert Nelson calls the economic norm that suffering is good for you if you are poor, “Calvinism without God.” It’s pure ideology shaped by previous religious convention.

“Our blog author has confused actual prosperity with a number, a redistribution as an increase. If the government stops spending, yes, AD drops (as data), but there’s not a dimes worth of difference in the actual prosperity of the nation.”

So exactly how do you propose to increase prosperity?

I think we ought to pay for it. Do you know anyone who will do something worthwhile for free?

Now, either the govt pays for it OR the private sector pays for it.

Richard “Answer this: Does the U.S. have more prosperity because of the AD increases caused by wars in Iraq and Afghanistan? Keynesian economics in one simple lesson: Invade thy neighbor.”-

The Nazis were the first government to implement Keynesian economics. They turned around the economy by building autobahns and then by building weapons. Reganomics was basically MMT- the star wars project was a way to increase aggregate demand. Lets face it, if every one burnt their neighbours house to the ground every 10 years or so there would be no unemployment. All of that is why I think it is extremely dangerous to not have waste and strife as the key evils and instead have unemployment and deflation as the key evils (as MMTers seem to do).

Tom,

Yeah, I re-read his post and you’re probably right.

It takes a much longer piece to explain it properly, without confusion.

Richard – is it beyond you to be a little less aggressive/discourteous?

I suggest you read more of Bill’s back blogs as you are missing a lot of the picture. It is all about deficit spending to deploy idle capacity – in particular unemployed people who want to work but which the private sector has not found jobs for. Such a person remaining unemployed for a year is a real resource which is lost to the economy – this has nothing to do with redistribution.

It does seem as if you are wilfully misunderstanding Bill/MMT and throwing muck around. But just in case you are genuinely confused:

* Iraq/Afghanistan:

– military expenditure has increased AD to the extent that, at the time when it was spent, there was spare capacity (meaning it wouldn’t ‘crowding out’ private spending; it would increase the military payroll and the revenues of US mercenary firms, some of which would be spent/invested in the economy. Of course, the multiplier effect of such spending is that much less when it destroys infrastructure (even another country’s). There are obviously good non-economic reasons not to invade other countries; are you seriously suggesting that because MMT highlights the economic benefit of military action, the adoption of MMT would lead to an even more militaristic foreign policy than at present?

* Foreign aid

-the lack of success of foreign aid in recipient countries is likely related to mechanisms of spending aid revenues within target economies – ie weak/dysfunctional/corrupt political institutions. Not really applicable to what MMT is on about, which is how it’s unwise to cut back on spending on domestic programmes when there’s such idle capacity and willingness to save on the part of the private sector.

* “If government spending causes prosperity, why not just keep on spending indefinitely?”

-MMT always says that deficit spending makes more sense the more space capacity there is in the economy; as AD approaches AS, deficit spending should be curbed.

Best wishes

M

I wonder about the effectiveness of spending in the UK. Surely there has already been a pretty significant spend due to Olympics preparations which surely should have created many jobs and spurred growth.

Perhaps this is the source of their high inflation at present.

Would be interested to hear from a Brit about this.

Ray yes there has been significant public investment the London Olympics infrastructure, which must have had some positive multiplier effect; but

Our persistent 3% CPI increases are speculated by the Bank of England to stem from energy and ccy depreciation effects; no one seems to believe this but I haven’t heard any plausible alternative explanation, when wage increases are all at 0-2% and broad money appears under control.

Best wishes

MMTP

More than a little sad when all is required is the political will to fix the homes …

Public Housing Repairs Can’t Keep Pace With Demand

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/25/nyregion/25repairs.html?pagewanted=2&partner=rss&emc=rss

Punchy said: “Is it the case that if I borrow from O/S and spend it in my country it does little or nothing for the country where the money came from but will create employment in my country. When I pay the money back to the O/S lender will it cost jobs in my country?”

I think it depends.

And, “As for Australian banks borrowing from O/S”

I’m not getting that part.

And, “so we can pay more and more for Houses (shelter) I just cant see how it adds anything at the Australian end of the deal. I wanted to know what it adds as we are doing plenty of it.”

Would it allow the private sector to be able to run a deficit for the trade deficit and/or budget surplus?

trade deficit = gov’t deficit plus private deficit

Typo :

The ‘M’ in the identity for the uses of national income (Y = C + S + T + M).

Thanks for pointing out that typo. I was wondering…

“The government says: ‘I will spend $100 on private sector activity which will provide the currency…’

How about the government says: “I will create a central bank and ‘borrow’ $200 from it and deposit that money in a private bank, which will gladly lend you $120 against $150 worth of real wealth that you have create by the sweat of your brow.” Our non-government person has no net DOLLAR savings, but he has $30 on his balance sheet if you count “inventory.” It is only the constraint of there being no third member of the economy to buy the inventory that prevents the first guy from having net savings. That third guy, of course, must also create some wealth in order to be able to borrow the $150 to buy what the first guy made, but that’s how real economies work. All the government has to do is seed the private banks with legal tender reserves; it never has to spend a nickle.

Lawrence J. Kramer says, “All the government has to do is seed the private banks with legal tender reserves; it never has to spend a nickle.”

When banks lend and create deposits, money is created (the deposit) but it nets to zero as the assets and liabilities are equal. No nongovernment net financial assets are created by credit extension. Moreover, money created through credit extension involves an interest obligation on the part of the financial sector in addition to the oblibation to repay the principal.

When government spends into the economy this increases nongovernment net financial assets with no obligation to repay on the part of the private sector or private sector interest obligation.

If the public wishes to net save, it needs net financial assets with which to do so.

“If the public wishes to net save, it needs net financial assets with which to do so.”

I’ve given an example of how an economy would work and people would accumulate wealth using only bank reserves created by Government printing (but not spending) and fractional reserve banking. If my model creates “no new net financial assets,” but does allow for the accumulation of net purchasing power by the public, perhaps the focus on net financial assets (money) simply swings at the wrong ball.

Prof. Mitchell’s two-person economy fails as a thought experiment because it does not allow for a number of players sufficient to enable fractional reserve banking. Without that possibility, the model is too hobbled to illustrate how T-accounts summing to zero does not negate the possibiltiy of net saved purchasing power and adequate liquidity to execute it.

Lawrence, see Bill’s post on fractional reserve banking here and here, for example. Also see the comments, especially by JKH and Scott Fullwiler. Banks don’t lend reserves.

Tom – I’m not looking for a primer on MMT. Let’s stay with your comment.

“When banks lend and create deposits, money is created (the deposit) but it nets to zero as the assets and liabilities are equal.”

If the bank lends against an asset, the only necessary “liability” is the encumbrance on the asset. There needn’t even be recourse against the borrower. Absent recourse, there is no offsetting liability on the borrower’s balance sheet except to the extent that the loan reduces the carrying value of the asset, which may be zero if the asset itself is carried at zero. If there is recourse, the borrower’s liability is a guaranty that the collateral will be worth the balance due. Such a guaranty can be valued at less than the total loan; indeed, it can often be insured through a third party for the payment of a small premium. When that happens, the insurer’s reserve for the claim is certainly less than the amount of the loan. Meanwhile, what you call “new net financial assets” – the money borrowed against the asset – are in the borrower’s SAVINGS account. Is there a useful definition of “saving” under which the borrower has not “saved” the amount of the loan, net of the value/cost of the guaranty, if any?

Recourse – creation of a liability – is a contractual term, not a necessary attribute of a secured loan. Unsecured loans to individuals create offsetting liabilities, but an unsecured loan to a corporationis just an encumbrance on the owner’s stockholdings. If the business can service the loan without using the proceeds, it can pay those proceeds to its owners, who can put them in the bank, again, as savings. Do you doubt that Facebook could borrow $1,000,000 tomorrow and pay it to Mark Zuckerberg as a dividend and that, if he is carrying his stock at zero on his balance sheet, he would not have net savings of $1,000,000 by virtue of the loan? Would it matter whether the bank making the loan got its deposits from the recipient of government spending or by government deposit without spending?

It all starts with the generation of real wealth in the real economy. Someone builds a house or a web site, hangs a shingle, or writes a song. If the result can be swapped for something else, it is wealth, and a bank will lend against it, asking recourse only to the extent its bargaining position permits. Thus, the money lent may or may not be offset by an accounting liability, and the recipient, or those who enjoy his custom or largesse, will have net savings, again, without Uncle Sam having spent any money. All that’s needed is for the government to create banking reserves by depositing money. The private sector will handle the rest.

Money is a medium of exchange. Governments create it as an accommodation; it allows people to quantify and homogenize their purchasing power. It could be created and disseminated for that purpose by a government that had no other function, i.e., that spent nothing on anything (and,therefore didn’t tax, so the idea of a model that starts with assumed taxation is really unhelpful). Net saving is simply surplus value added, i.e. purchasing power not yet exercised. It is a real phenomenon, not a monetary one.

As for fractional reserve banking, I don’t see the difference – vis a vis the claim that private savings require a public deficit – between the standard model whereby reserves precede loans and the MMT model where loans drive reserves. Actually, I don’t see any policy implications of the difference either. Apparently, the cost of money to the bank is affected by the Fed’s degree of accommodation, so the bank’s hurdle rate (a function of the spread it charges and creditworthiness it demands) also depends on that degree of accommodation. In other words, if the Fed eases, the bank can make money on loans for which there is a greater demand than if money is expensive. Since banks create money by lending, the cost of money determines (ceteris paribus) how much lending is done, and, thereby, the money supply.

Do you not agree that (i) real wealth can be created without money, or (ii) money can be created merely to provide a medium of exchange for real wealth, or (iii) that real private wealth can reasonably be called “net private savings”?

Lawrence says, “Do you not agree that (i) real wealth can be created without money, or (ii) money can be created merely to provide a medium of exchange for real wealth, or (iii) that real private wealth can reasonably be called “net private savings”?”

(i) Difficult in a money economy, certainly on any scale that would matter much without slavery.

(ii) The chief purpose of money is as a medium of exchange. Money is a financial asset used to facilitate transactions involving the exchange of both real assets and other financial assets.

(iii) Depends on what you mean by “savings.” If savings = net worth, then it includes all assets, financial and real. But that does not affect the fact that net financial assets are created by government deficit expenditure, or that the national “debt” as the accumulated deficits is the total nongovernment saving of net financial assets. This is just states that the net financial assets created by deficits gets saved as tsy’s due to the politically imposed requirement of a S-4-$ deficit offset with tsy issuance.

It is funds flowing through an economy, some of which are committed to productive investment, that results in the increase in real assets, i.e., real wealth as part of net worth. Some portion of income is not consumed and is saved as financial assets, e.g., bank accounts or bonds.

Government inject and withdraw net financial assets, banks create debt-based funding, and productive investment creates consumable products and real assets.

“I’ve given an example of how an economy would work and people would accumulate wealth using only bank reserves created by Government printing (but not spending) and fractional reserve banking”

Seeding state money into private banks is state spending. The state is getting nothing of real value in return for its scrip.

That system is entirely consistent with MMT, although I’m sure that the theorists would suggest that there are more efficient means to fire an economy up than state spending into the private banking system.

Tom –

i. “Difficult” is not “theoretically impossible,” which I understand to be the claim. I’m not advocating a money-free society, just noting that there is no theoretical obstacle.

ii. Fine. Then there is no reason why it needs to be “spent” into existence as opposed to lent into existence.

iii. What about non-recourse, fractional reserve bank loans against collateral carried at zero, which create no offsetting liability? Are they not net private savings?

Neil –

What I call “seeding” can be accomplished by the government lending to the bank, i.e., opening an interest-bearing account. That’s not what is actually happening here; the gov’t is IN FACT running a deficit. But we’re talking necessary identities here, and I’m just saying that government spending is not LOGICALLY necessary to the creation of money by the banks against real wealth without recourse.

Neil – Let me clarify, that the government gets nothing for its scrip is irrelevant to the claim that deficits=savings if the loan to the bank doesn’t create a deficit. If the Treasury books an interest cost for its loan from the Fed, we can hypotheize an interest payment by the bank to the Treasury, The result: no federal debt, but money available to lend without recourse against zero-carry-value assets.

Lawrence, admittedly it is possible to set up a system in a variety of ways, all of which have consequence, e.g., barter system with no money permitted (yes, there are some people who use no money as a matter of principle), only state money with no bank money creation, only bank money creation with no state money creation, private banking seeded with state money as you suggest, vertical-horizontal system as at present, convertible flexible rate or nonconvertible floating rate, etc. There are a lot of proposals being floated around right now.

MMT is a description of the operations of the existing system, what they entail, and how to improve outcomes by taking advantage of the opportunities of the current system. There are also suggestions for tweaks to the existing system by removing politically imposed restrictions in various currency zones.

I’m fine with what MMT purports to be. I’m just questioning one simple, apprarently fundamental tenet: an accounting identity between net private savings and net public debt. I cannot square that identity with either the theoretical possibility of (i) HPM being created by unspent government bank deposits, or (ii) bank-created money lent against previously unaccounted for value added. If the identity doesn’t hold, how much of the MMT edifice remains? If it does hold, how does it handle the two phenomena I have noted, especially the latter, which in fact takes place in our economy every day?

Lawrence: “real private wealth can reasonably be called “net private savings””

You can call anything anyhow and build any theory on any basis you like but you need to be aware that your definitions can go against commonly accepted practice, rules and assumptions. But then it will be you who has to defend your definitions.

National accounts is the system approved and recommended by United Nations for use in all countries and it defines savings in purely nominal accounting terms. Within national accounts your house is not your savings regardless of how you personally think about it.

_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_accounts

Sergei – The issue isn’t nomenclature; it’s existential economics. I’m happy to use the definition you propose, but then you have to defend its relevance to economic reality. What does the identity that exists under the definition you favor betoken? I can’t see why anyone would want to measure “net private savings” under your definition except as an observable thing that has historically correlated with some less directly measurable phenomenon. Weatlh, as perceived by its holders, drives economic activity (that there being my defense of my definition). If “net private savings” doesn’t measure wealth, what does it measure that matters? And if it doesn’t measure something that matters, why do we care that it equals the net public deficit?

Lawrence,

Your instincts are good but I’m afraid that you’re unlikely to get sensible answers to your questions here. There is nothing tying the flow of real saving to the flow of nominal saving net of the flow of nomnal investment (what does this value signify in any case?). Real saving and MMT net saving are not the same thing.

“It is funds flowing through an economy, some of which are committed to productive investment, that results in the increase in real assets, i.e., real wealth as part of net worth. Some portion of income is not consumed and is saved as financial assets, e.g., bank accounts or bonds.”

Tom, you’ve either been mislead or you’ve somehow managed to confuse yourself. The correct version is, “some portion of output–a flow of real resources–is not consumed (i.e. is saved) and is used to finance real investment.”

REAL saving is given, in a closed economy, by,

S = Y – C – G

Where S is the flow of unconsumed real resources (goods and services) available for investment.

Lawrence, we all live in the monetary economy. Savings in monetary economy by definition is monetary income not spent. Net private savings measure the monetary wealth of the private sector in aggregate. This wealth is not about perception or relevance but about accounting facts, where accounting was invented to reflect the monetary reality.

Sergei –

What on earth are “accounting facts”? We wouldn’t need GAAP if accounting were about facts. Accounting is about homogenized reporting. Accounting is about book values; economics is about market values. Any presccriptive economic program that looks to accounting identities is doomed to fail.

But meanwhile, I’m still waiting for SOMEONE to explain to me how non-recourse loans against unrealized gains figure into the claim that bank lending creates no new net financial assets. What are the T-accounts on the transaction? It seems to me that the bank debits loans and credits cash, but the borrower debits cash and credits equity, i.e., net financial assets. Can you plug that hole in my understanding?

“Savings in monetary economy by definition is monetary income not spent. Net private savings measure the monetary wealth of the private sector in aggregate.”

I don’t think either of these statements is correct. Nominal saving (singular; flow of) is monetary income not spent on consumption. Net private saving (singluar; flow of) refers to the balance of payments between private and non-private sectors in the economy. It measures relative flows of nominal expenditure between them.

Lawrence,

“It seems to me that the bank debits loans and credits cash, but the borrower debits cash and credits equity, i.e., net financial assets.”

I think you are correct. There was quite a bit of discussion of this in the comments in the not too distant past. Anon to thread!

Lawrence:

You are making some interesting points, but I am not sure about the technicalities you use:

”

but an unsecured loan to a corporationis just an encumbrance on the owner’s stockholdings.

”

Unsecured loan is as much of a company liability as the secured one — not clear why you apparently disagree with this. It does not matter if you call it “encumbrance” or “debenture” or whatever, the debt extraction mechanism may be different legally speaking, but an unsecured loan it is still a liability on the debtor books.

”

Do you doubt that Facebook could borrow $1,000,000 tomorrow and pay it to Mark Zuckerberg as a dividend and that, if he is carrying his stock at zero on his balance sheet, he would not have net savings of $1,000,000 by virtue of the loan?

”

Not sure what you are saying here.

MZ’s stock book value being zero or any other value, as well as his balance sheet, are irrelevant to the way the company pays his dividends. If the company took a loan to pay the dividends, the loan, secured or otherwise, is the company’s liability, not MZ’s.

”

Would it matter whether the bank making the loan got its deposits from the recipient of government spending or by government deposit without spending?

”

The bank that made the hypothetical loan to MZ needs zero deposits (abstracting from some complications arising from interbank settlement requirements aka “liquidity” management).

”

I can’t see why anyone would want to measure “net private savings”

”

I share you discomfort with respect to the above.

Lawrence:

“but the borrower debits cash and credits equity”

The borrower debits cash and credits his liability (the “Loan to Repay” account).

“Equity” is an accounting fiction being a difference between total assets and liabilities book values.

The act of loan granting does not change either the borrower or the lender capital/equity book value at the moment the loan is granted.

Net “private” savings is different from “real savings” as Vimothy pointed out.