I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

When miracles lose some shine

It is a fact that the Australian economy escaped recording a technical recession (2 consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth), having recorded only one negative real GDP quarter (December quarter 2008 = -0.7 per cent). In that quarter, the first of large fiscal stimulus measures began and growth accelerated after that. The downturn, however, did push up official unemployment and underemployment and the legacy of the rationed employment and hours growth is that Australia currently has a broad labour underutilisation rate of 12.5 per cent. Aggregate policy (fiscal and monetary) is now tightening and is being justified by official statements that the economy is about to explode on the back of a very strong commodity boom (mining) and that we are close to full employment anyway. We are being told that unless policy tightens now inflation will break out. The problem with the official rhetoric is that a sequence of data releases is telling a different story. In the past few weeks we have seen exports falling, a weakening construction sector, flat credit demand, and yesterday, a very weak investment outlook. The outlook for next week’s September quarter National Accounts data is becoming increasingly pessimistic. In the meantime, unemployment rose in October. The justifications for the policy tightening are vanishing although I would argue they never were credible in the first place. The miracle Australian economy is a little less shiny at present.

In November, the Reserve Bank of Australia increased interest rates by 0.25 basis points even though the most recent evidence indicated that inflation is falling. The commercial banks all followed the decision by increasing rates well above the 0.25. A furore erupted about whether bank funding costs had been rising or whether the increasing spread between the RBA policy rate and the bank mortgage rates represented gouging behaviour.

The best analysis I have seen of that controversy comes from our friend Sean Carmody – Bank funding costs. Sean is an “bank insider” and knows what is going on. Conclusion:

… while it may be true that wholesale funding costs are still increasing, it would appear that banks have already charged home buyers far more than the increase in costs the banks have suffered.

That is one thing. But I am more interested in the rationale for the monetary policy tightening.

I also note that in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2010-11, which was released on November 2, 2010, the Government said:

The Australian economy is growing solidly as a self-sustaining private sector recovery takes hold. Output and incomes growth are strengthening and unemployment is falling … Australia’s terms of trade … [are] … around record highs. This is expected to provide substantial impetus to domestic growth, supporting rising incomes and activity, underpinned by strong growth in exports and business investment.

The Australian economy is expected to grow above trend over the forecast horizon and, with an already tight labour market, reach capacity within the next year or so.

In fact, the October Labour Force data showed that unemployment rose sharply.

And subsequent data that has been released (credit, construction activity, exports, and now business investment) are all point to a slowing economy that is presently a considerable distance from “full capacity”. I will come back to this evidence.

The RBA has also been propagating the “above trend growth” – “full capacity” – “full employment” myth as a justification for its interest rate decisions.

The alternative hypothesis to describe the rhetoric of the Government and its central bank is that the neo-liberal bias towards fiscal conservatism (which is really better described as fiscal destruction given the move into surplus undermines private wealth and income generation) is being re-asserted in the hope that the export sector will deliver strong demand growth.

This is the mainstream dream world – sit back and ship your real resources to other nations and restrict domestic activity via tight fiscal and monetary policy which manifests as persistently high labour underutilisation rates. The research agenda here is to articulate who gets the “rents” from this sort of policy bias. The most disadvantaged workers certainly bear the brunt of this approach.

In the Minutes to the November RBA Board meeting we read:

The labour market remained strong. The unemployment rate was unchanged at 5.1 per cent in September, with employment increasing by a further 50,000 in the month, and by around 3¼ per cent over the year. Members noted that other evidence suggested that the labour market might not be as tight as indicated by the unemployment rate.

As noted above, the unemployment rate rose, employment growth has been falling and relying on part-time (casualised, low-pay) employment growth and the only thing that stopped the situation from being worse is that labour productivity growth is fairly stagnant. One of the casualties of persistently high labour underutilisation rates and rationed working hours is that there is weak real wages growth and no incentive by firms to lift productivity growth.

It is the veritable “race to the bottom” growth strategy and that approach has characterised the Australian scene for two decades now.

The RBA also noted how fragile the world economy is at present. Certainly all those Eurozone bosses who around mid-year claimed that their crisis was all but over should be eating their words now. The only thing stopping the Eurozone from total meltdown is the ECB “fiscal policy” initiatives (buying member government debt in the secondary markets. It is the bailout you have when you are not officially having one but stands in stark contradistinction to the spirit and logic of the EMU. In other words, it demonstrates what a failed monetary system the EMU is.

But having noted the fragility of the World environment (which has deteriorated since the Board met) the statement of the RBA Governor concluded that:

… the economy is now subject to a large expansionary shock from the high terms of trade and has relatively modest amounts of spare capacity …

The claim that we are growing on trend and near full employment is a repeating theme propagated by the mainstream economists, the Government and its central bank.

Do a search and you will find countless articles and media appearances by journalists and financial commentators (including all the bank economists) stating that Australia was near or at full capacity and that inflation was about to surge as we pocketed untold income and wealth from the expansion of our exports sector.

In the May Budget Speech, the Federal Treasurer said:

Our economy and fiscal position remain among the strongest in the world. We have more robust growth, lower unemployment and lower debt than our peers.

Our economy is expected to rebound powerfully, with forecast real GDP growth of 3¼ per cent in 2010-11 and 4 per cent in 2011-12.

Best of all, the unemployment rate is expected to fall further from 5.3 per cent today to 4¾ per cent by mid-2012, around the level consistent with full employment.

The Australian economy is today in an important transition phase. Fiscal stimulus is winding back as planned.

So the discussion was turning to the inflation threat from this once-in-a-century mining boom. We were being conditioned by the public commentary to accept the idea that a 12.5 per cent broad labour underutilisation rate was “near” full employment. The discussions started turning to further labour market deregulation to force the lazy workers to take jobs.

On this theme, see the latest OECD progress report on its Making Reform Happen agenda. The OECD is pushing the line that:

Governments must reform labour markets, pensions, healthcare, and taxes to help their economies recover from the financial crisis.

Which reads: make it harder for workers via lower pay, more insecure jobs etc; cut pension entitlements except for the CEOs of the corporations; privatise health case and exclude the disadvantaged from public care; and reduce taxes for the high income earners.

The problem with all this conjecture and lying is that policy decisions (tightening fiscal and monetary policy) have actually been informed (and justified) by it. The reality – that is, what is happening in the real economy certainly was not following the neo-liberal script. When I was raising the “slow growth – keep the fiscal support going” alarm in my media appearances in the last 12 months I was dismissed as “Mitchell again”.

Well now the evidence that I predicted is seeping out of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and everyone can see that the official data is showing that things are not as rosy as we were led to believe.

A bank economist yesterday (after the investment data came out) actually admitted we could be in for a negative GDP quarter in September. As part of the process of releasing the final National Accounts data, the ABS progressively releases data of the aggregate demand components. As each piece of information comes out over a period of a few weeks in the lead up to the final release you start to get a feel for what the final data will tell us.

The final National Accounts data comes out next Wednesday but the unfolding message from the data already published is real GDP growth will slow and certainly not be close to trend. The first piece of evidence was the Labour Force data which I analysed in detail in this blog – The plight of the unemployed – under growth and decay.

So pessimism was already setting in as it became clear that the withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus and the tightening monetary policy was cooling the labour market even before we started to eat into the underutilisation in any serious way. When you have employment growth slowing and unemployment rising things are not looking good.

Construction

On November 24, 2010, the ABS released its latest data for Construction Work Done (September quarter, 2010).

The main results in real terms (seasonally adjusted) were:

- Total construction work done fell 2.1 per cent in the September quarter.

- Total building work done fell 2.7 per cent.

- Total engineering work done fell 1.4 per cent.

I provided some detailed analysis in August in this blog – Fiscal stimulus and the construction sector – which predicted these trends.

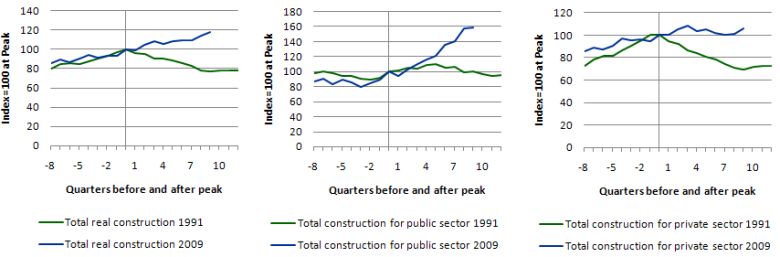

In that blog I produced the following butterfly graphs. butterfly plots for total construction, public construction and private construction for the 1991 and 2009 downturns. The indexes are set at 100 for the peak in total construction in the 1991 and 2009 downturns. They show the four quarters before the peak and the 12 quarters after the peak for the 1991 recession and 7 quarters after the peak for the current episode.

The behaviour of this important recession bell-weather sector was starkly different this time largely as a result of the fiscal stimulus which was targetted on the construction sector.

It is clear that the fiscal stimulus provided scope for the construction sector to keep growing during the recession and helped maintain positive employment growth.

As the fiscal stimulus is withdrawn, construction is now in decline and it is clear that private sector spending is not yet rising to fill the spending gap. This will temper real GDP growth and cause the labour market to deteriorate further.

Exports

Earlier (November 2, 2010), the ABS released the September quarter International Trade in Goods and Services data, which provided us with a clearer idea of what the “record terms of trade” is doing for aggregate demand.

The main results in seasonally adjusted terms were:

- The Balance on goods and services remained in surplus but declined sharply in the September quarter.

- Exports fell by 2 per cent.

- Imports rose by 1 per cent.

The ABS also noted that “Between August 2010 and September 2010 the trend estimate of goods and services credits fell $79m to $24,942m”. They also pointed out that imports of capital goods fell by 4 per cent.

So in summary a declining net exports contribution which will also temper real GDP growth in the September quarter.

Lending finance

On November 15, 2010, the ABS released the September Lending Finance data.

The trends described by that data were negative:

- The value of owner occupied housing commitments excluding alterations and additions rose 0.7 per cent.

- The value of total personal finance commitments fell 0.1 per cent.

- The value of total commercial finance commitments fell 1.3 per cent.

While there were mixed signals here, the fall in trend commercial finance does not suggest an investment boom is underway yet.

Investment

Yesterday (November 25, 2010), the ABS released the September quarter – Private New Capital Expenditure and Expected Expenditure – which gives is a solid predictor of what will happen to real GDP growth.

The data provides backward-looking information (actual expenditure for the September quarter) and forward-looking or expected expenditure. The quarter-to-quarter data can be very volatile and so it is usually better to consider the trend movements in this series as an indicator of what is happening.

The main actual expenditure features were:

- Trend total new capital expenditure rose by only 1.5 per cent in the September quarter 2010, which is only a modest pick up. To put this in perspective, at the height of the boom in the last growth cycle, we saw trend quarterly growth of 6.7 per cent. Again, during the last peak rates of growth of 11 per cent were observed.

- Total investment in equipment, plant and machinery fell by 4.8 percent (also the seasonally adjusted estimate fell).

So modest growth (below past peaks) in some of the components and a sharp fall in equipment, plant and machinery investment. It is this last result that has led some economists to revise their overall real GDP growth estimates for the September quarter downwards.

My interpretation is that investment is still positive overall and will contribute to real GDP growth but the data is hardly signalling a boom as yet.

To get an idea of what the future holds, given the RBA is continually telling us the place will explode in 2011 and 2012 if they don’t scorch the economy now, the expected investment expenditure data is interesting.

Some of the ABS expected measures suggest that investment may grow strongly in the coming years but, equally, there are other measures (they produce several different expected series) which indicate a fairly modest investment outlook.

To repeat: probably positive but no out-of-control boom.

RBA statement to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics

Given this negative data, the appearance of the RBA governor, Glen Stevens before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics this morning was interesting.

He was interrogated about the recent tightening of monetary policy in the face of deteriorating economic data. The Governor claimed that monetary policy tightening had stopped for “some time”. The Transcript is not yet available.

The logic of the Governor’s statements are outlined in the Opening Statement that the Governor provided the Committee.

He said:

Over the coming year, we think that inflation will be pretty close to where it is now, consistent with the target. But looking further ahead, in an economy with reasonably modest amounts of spare capacity, the terms of trade near an all-time high and the likely need to accommodate the largest resource-sector investment expansion in a century, it is pretty clear that the medium-term risks on inflation lie in the direction of it being too high, rather than too low.

So he is still propagating the full capacity-inflation threat mantra. I guess if he says it enough some part of the story may eventually turn out to be true. But at present you cannot see this in the unfolding data.

Press reaction

Melbourne Age economics writer Peter Martin wrote an article today (November 26, 2010) – Cloudy horizon but economic forecast still strong – and put together the recent “bad” economic news.

He said that:

NO ONE is talking recession but financial market economists are seriously considering the next worst thing – an end to Australia’s extraordinary run of economic growth.

The gross domestic product figure for the September quarter, to be released on Wednesday, will be weighed down by a surprise hit to exports, extremely weak residential construction, a dent in public construction as government stimulus programs wind down, and figures released yesterday showing a slide in private investment in equipment and machinery.

I wouldn’t be guided by what the “financial market economists” think but the reality that Peter Martin is describing is clear from the data.

Martin reports that the bank economists are now revising their growth forecasts down. One of the big four has the September quarter real GDP growth coming in at 0.3 per cent (1.2 per cent annualised).

With labour productivity running around 1 per cent per annum and labour force growth around l.3 per cent (conservative) then expect the unemployment rate to jump again later in the year or else hours of work will fall sharply. Overall, a rate of growth of 1.2 per cent per annum is significantly below trend and makes a mockery of the policy tightening that has been going on.

The alternative view of yesterday’s investment figures comes from Fairfax journalist Michael Pascoe – Full speed ahead, ignore the puffer fish – in which he provides a fairly realistic account of the data.

He notes that the negative reaction of the bank economists to the fall in equipment investment was a bit over-the-top and that:

What attracted some attention was a 1.1 per cent dip in spending on plant and machinery in the September quarter. To the average centipede, 1.1 per cent is not exactly a headline. And it’s historical. While the CFOs spent a little less on printing presses and rock crushers in the September period compared with the June quarter, they still told the ABS they’re expecting to spend 3.3 per cent more this year than they were budgeting for three months ago.

A fairer reading is the planned spend on plant and equipment is about steady on last year’s quite high level – remember the government incentives for small businesses to go out and buying something? And then maybe you might want to consider how much more bang companies are getting for the same number of Aussie dollars anyway.

That assessment is fair enough. But taken it as stated it still signals that the economy is not growing on trend. The Government and RBA is betting on the resources boom being so strong that the weakness in spending everywhere else in the economy (tightening budget, consumer spending flat) will be more than compensated for.

Eventually, the resource boom might deliver the huge investment bounty that is implied by this view. But in the meantime it is the government’s responsibility to ensure they keep spending as close to capacity every quarter so that the potential of our available labour resources is maximised.

You would have to conclude that the policy framework is thus failing us at present especially when excess capacity is rising (capital and labour) and inflation is falling.

I will never support this neo-liberal mantra of “forward-looking” policy settings which justify pro-cyclical policy changes which is what is happening at present. Inflation doesn’t just burst forth and the Government would have plenty of opportunity to choke it when the signs are all strongly positive.

There is never a justification to deliberately keep people from being able to work when inflation is falling and the other signals about the real economy are consistently negative.

Conclusion

While there are strong demand signals coming from the mining sector the overall economy is not performing as the official rhetoric is suggesting.

Aggregate policy has been tightened way to early and the damage is becoming evident. Try telling the rising number of underutilised workers who want more jobs and hours of work that we are “close to full capacity”.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – to give you something to do over the weekend. I have made it easier this week!

That is enough for today!

There’s something unavoidably funny when literary journals are getting ahead of mainstream economic publications! The “London Review of Books”, not hosting, of course, political or social editorials for the first time, recently put out an opinion article about the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government’s budget plns for the United Kingdom.

Sample :

“Then there is our old friend ‘crowding out’: allowing high levels of government borrowing to ‘crowd out’ private investment by forcing up interest rates beyond levels the private sector can afford. It was a popular notion in the interwar years and has been retrieved and dusted down by those who defend the spending review, but it too surely is play-acting. There was little enough evidence of it in the interwar years; today there is none. With short-term interest rates almost at nil and long-term rates low, it can’t be argued that private borrowers are being ‘crowded out’. If they are not borrowing for investment it is because they reckon current levels of aggregate demand don’t justify it.”

Link : http://www.lrb.co.uk/v32/n22/ross-mckibbin/nothing-to-do-with-the-economy

“In other words, it demonstrates what a failed monetary system the EMU is.”

If the EMU countries dig the hole they are in, with enough energy and the right direction, they will get out in China. 🙂

Bill

I would be very interested to hear about your analysis of Iceland in contrast to the situation in Ireland (as Krugman has suggested) as being different due to the fact that Iceland has a sovereign currency.

Best regards and thanks much for you enlightenment.

Sid

@sidchem.

I take it you have read the Iceland blogs:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=7161

along with:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=11854

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=8457

There are a few commentators out there pointing to Iceland as the reason why floating exchange rates won’t save a country.

Floating exchange rates don’t stop a country and its politicians making stupid decisions unfortunately.

Great, bring it on! Might be able to afford to buy a house….if I still have a job.

A very good synopsis of the US political response (that is, lack thereof) to the GFC by somewhat neo-liberal economist Brad DeLong (http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/11/battered-but-not-beaten.html).

Good to see someone with a little mainstream credibility skewer the economics profession.

DeLong above reveals a little bit of the MMT NFA gene:

“Moreover, when the federal government spends and does not tax it borrows to finance it. That borrowing means that it issues bonds–and U.S. Treasury bonds are, now more than ever, high quality safe AAA-rated financial assets. By expanding the supply of safe assets the government diminishes the excess demand gap between what the market wants to hold in the way of safety and what it can hold, and the reduction in the size of that gap reduces its mirror, the deficient demand for currently-produced goods and services.”

DeLong and Krugman seem to be inching toward an MMT vantage, probably given cover as well as a little prodding by Jamie Galbraith. I suspect a lot of smart people are getting increasingly concerned that the car is hurtling toward the edge of the cliff, and they are getting less protective of their investment in previous positions. I think that Bernanke is one of them, too. This is going to be getting interesting unless things turn around. But with the EZ heading for the abyss and the US set for political gridlock, with the GOP open to a double dip to take down Obama, and China seemingly groping, too, a turn around doesn’t seem to be in the cards anytime soon. Odds seem heavily weighed toward debt deflation.

I thought the recent essay “The Instability of Moderation,” by Professor Krugman was also quite good.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/26/the-instability-of-moderation/

back to Oz…..today’s partial GDP data were a shocker….inventories and profits….meaning that if we don’t get a -ve number for Q3 GDP, it’ll be darn close. No wonder Stevens backtracked on Friday. If it’s not the sharply escalating muppet show of the Eurozone, it’s a local economy that is underperforming the hype.