I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal stimulus and the construction sector

I come across new evidence every day that supports the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective on fiscal policy. Today the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest Construction data which provides very clear testimony to the effectiveness of the recent fiscal interventions in Australia. So I thought I would devote this blog to exploring some of the characteristics of this data and see what it means for assessing the impact of the fiscal stimulus in Australia. The conclusions that I draw are consistent with the insights that many different data series are telling us at present. The fiscal stimulus was effective and as it is withdrawn by a budget surplus-obsessed government the economy is suffering. The data today is a further nail in the deficit terrorist coffin.

In early 2009, the director of the Australian Housing Industry group said:

January was another poor month for the construction industry, with the relentless pressures of tight credit conditions and deteriorating economic sentiment driving a further decline in activity

The following graph is taken from the latest edition of the Australian Industry Group-Housing Industry Association’s – Performance of Construction Index – which “is a is a leading economic indicator of business activity in the Australian construction industry, covering residential building, non-residential building and engineering construction”.

You can see that as the world recession deepened in the second-half of 2008, the index fell sharply as the industry began to contract. The pattern was replicating the performance of the construction industry in past recessions.

So things were looking dire and the construction industry employs a lot of people in Australia. In response, the Australian government acted quickly and introduced a staged fiscal stimulus of substantial proportions (relative to GDP and the responses of other governments).

The Australian fiscal stimulus and construction

In Australia, the first fiscal stimulus package (October 2008 – the Economic Security Strategy) mainly consisted of cash handouts to pensioners and families. There was an extension to the First Home Owner Grant Boost and some training places offered.

However, the second package (the Nation Building Package) focused on infrastructure development. This was followed in February 2009, as the recession looked like deepening with the $A41.5 billion (that is, economically significant with respect to GDP) allocated to the Nation Building and Jobs Plan.

While there were further cash handouts the bulk of the proposed spending was focused on the contruction sector (educational infrastructure development, social and defence housing and the home insulation scheme.

The early cash payments timed initially to coincide with the xmas spending rush in December 2008 were designed to put increased purchasing power into the hands of those who would spend it quickly. The evidence supports the argument that this occurred.

The infrastructure spending was concentrated on schools and there were several arguments mounted to support this part of the stimulus plan. First, there are schools in every locality – where people live and work. Second, the construction industry is big with about 1 million workers and it always contracts severely in a recession. Third, construction in schools could be implemented without delay (land availability, less applicable local planning regulations). Fourth, the specific building plans could be used throughout the nation.

This part of the fiscal stimulus was thus designed to support an industry that typically contracts early and significantly in any economic downturn.

A further $A$22.5 billion was announced in the May 2009 budget for the Nation Building Infrastructure program.

It was clear that private construction was in decline but the stimulus packages (specifically the school hall packages) was kickstarting the overall construction industry and preserving employment in that sector.

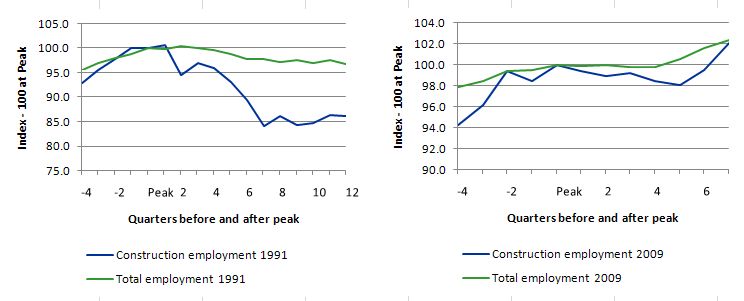

The following graph shows what happened to construction industry employment relative to employment overall.

The following butterfly graphs are constructed from ABS Labour Force by Industry data. They are employment indexes set at 100 for the peak in total employment in the 1991 (left-panel) and 2009 (right-panel) downturns. They show the four quarters before the peak and the 12 quarters after the peak for the 1991 recession and 7 quarters after the peak for the current episode. They provide a very good picture of the different fortunes encountered by total employment and employment in the construction industry during the respective downturns.

It is clear that the construction industry and total employment in the current downturn behaved very differently to the 1991 episode. The 1991 recession saw typical behaviour and a reluctance by the federal government of the day to engage an early and signficant fiscal stimulus. The willingness of the Australian government in 2008 to introduce a substantial fiscal intervention sets the two periods apart.

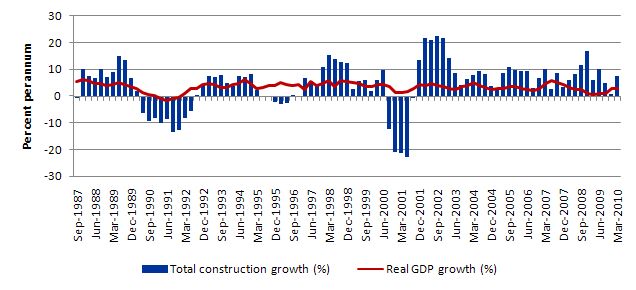

The next graph is taken from the ABS Construction Work Done data released today (August 25, 2010) and ABS National Accounts data and shows the annual growth in Total Construction (blue bars) and real GDP (red line) from September 1987 to June 2010. The period captures the 1991 and early 2001 downturns and the recent downturn.

It is clear in the 1991 and 2001 downturn total construction fell in line with real GDP contractions. But the pattern was broken in the recent downturn.

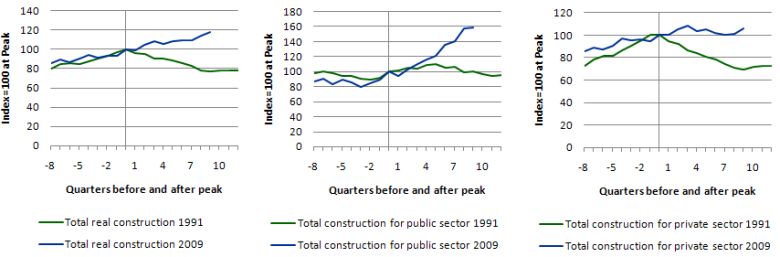

The next graph compiles butterfly plots for total construction, public construction and private construction for the 1991 and 2009 downturns. The construction of the butterfly graphs are explained above.

The behaviour of this important recession bell-weather sector was starkly different this time largely as a result of the fiscal stimulus which was targetted on the construction sector.

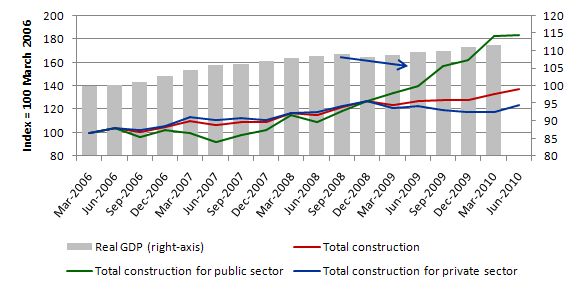

This graph shows the recent period is more detail. It serves to reinforce the point that I am making in this blog. The blue arrow shows the one quarter contraction in real GDP that occurred just before the stimulus impacts began to take effect. After that the surge in spending supported both positive real GDP growth and a strong construction sector.

Some might argue that the easing of monetary policy also had an affect. The Treasury estimated that it was very minor compared to the fiscal impact.

In this blog – Lesson for today: the public sector saved us – I discussed a report from the Australian Treasury (December 8, 2009) – The Return of Fiscal Policy.

They said:

Chart 10 shows Treasury’s estimates … of the effect of the discretionary fiscal stimulus packages on quarterly GDP growth. These estimates suggest that discretionary fiscal action provided substantial support to domestic economic growth in each quarter over the year to the September quarter 2009 – with its maximal effect in the June quarter – but that it will subtract from economic growth from the beginning of 2010.

The estimates imply that, absent the discretionary fiscal packages, real GDP would have contracted not only in the December quarter 2008 (which it did), but also in the March and June quarters of 2009, and therefore that the economy would have contracted significantly over the year to June 2009, rather than expanding by an estimated 0.6 per cent.

They also estimated the impact of the rapid reduction in interest rates by the Reserve Bank on GDP growth rates and concluded that:

…this fall in real borrowing rates would have contributed less than 1 per cent to GDP growth over the year to the September quarter 2009, compared with the estimated contribution from the discretionary fiscal packages of about 2.4 per cent over the same period.

So discretionary fiscal policy changes are estimated to be around 2.4 times more effective than monetary policy changes (which were of record proportions).

Construction in the US and Australia

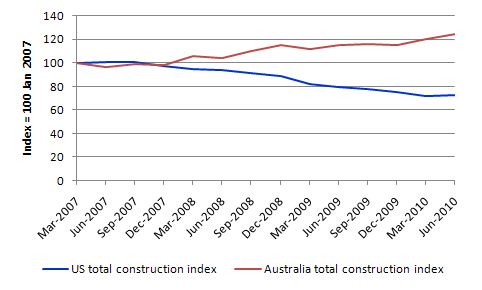

The following graph compares the fortunes of the construction sector in Australia and the US from the first quarter 2007 to the June 2010 quarter. The US data comes from the US Census Bureau. The lines are indexes set at 100 in the first quarter 2007.

The graph provides some of the explanation as to why the Australian economy has been less severely affected by the recession. The differences have been driven by the different focus and scope of the respective fiscal interventions.

Fiscal stimulus and waste

There has been a lot of discussion about the waste of the fiscal stimulus packages. The words of Joseph Stiglitz resonate on this issue.

He was was interviewed recently on the ABC national current affairs show 7.30 Report. You can see the full transcript to see what he said or watch an extended version of the segment.

Here is the relevant exchange in regard to the stimulus packages and the allegations of waste:

Interviewer: I’m not sure how much you know about Australia’s stimulus packages in response to the crisis, but to the extent that you do, how did the quality of Australia’s stimulus compare with that in the US and elsewhere, in terms of its effectiveness?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: I did actually study quite a bit the Australian package, and my impression was that it was the best – one of the best-designed of all the advanced industrial countries. When the crisis struck, you have to understand no-one was sure how deep, how long it would be. There was that moment of panic. Rightfully so, because the whole financial system was on the verge of collapse. In that context, what you need to act is decisively. If you don’t act decisively, you could get the collapse. It’s a one-sided risk.

Interviewer: There’s been a lot of criticism of waste in the way some of Australia’s stimulus money was spent. Is it inevitable if you’re going to spend a great deal of government money quickly that there will be some waste and can you ever justify wasting taxpayers’ money?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: If you hadn’t spent the money, there would have been waste. The waste would have been the fact that the economy would have been weak, there would have been a gap between what the economy could have produced and what it actually produced – that’s waste. You would have had high unemployment, you would have had capital assets not fully utilised – that’s waste. So your choice was one form of waste verses another form of waste. And so it’s a judgment of what is the way to minimise the waste. No perfection here. And what your government did was exactly right. So, Australia had the shortest and shallowest of the downturns of the advanced industrial countries. And, ah, your recovery actually preceded the – in some sense, China. So there was a sense in which you can’t just say Australia recovered because of China. Your preventive action, you might say pre-emptive action, prevented the downturn while things got turned around in Asia, and they still have not gotten turned around in Europe and America.

I always remind readers that there is no greater waste than persistent unemployment. It dwarfs all other inefficiencies.

Further, I am often asked in media interviews about the waste involved in the fiscal intervention. I always make the point that it is possible that some parts of the stimulus intervention (a relatively minor proportion of total funds spent) were problematic in terms of adminstrative issues. I refer to the now-scrapped insulation program. There has been a major beat up about this program in the media but the facts are in dispute. I would conclude it wasn’t a very good program but the facts that are available are very blurred.

But the point I made was that large-scale stimulus interventions of the type taken by the Australian Government – which in international terms was early and large relative to GDP – are very complicated and you can expect some administrative inefficiencies. Imagine if the private sector had to ramp up investment spending within a quarter or so – what do you think would be the outcome of those projects.

I also indicated that the neo-liberal era has been marked by a major reduction in Departmental capacity to design and implement fiscal policy – given the obsession with monetary policy and the major outsourcing of “fiscal-type” government services to the private sector. Many of the major Federal government policy departments are now just contract managers for outsourced service delivery. So with the voluntary reduction in “fiscal space”within the federal government over the last 20 years or more it is no surprise that the overall capacity of the government machine to implement efficiently and speedily complicated nation-wide infrastructure programs has been diminished.

This is a lesson for the future in my opinion. We can no longer deny that fiscal policy is required to address serious swings in private spending. Monetary policy has been proven – categorically – to be ineffective in dealing with aggregate demand failures of the sort we have witnessed in the current crisis. In that context, governments must develop forward-looking capacity to ensure that it has project implementation skills when they are required.

Having said that, I also point out in interviews that while complex interventions will not be perfect in design or execution you have to consider what would have been the case if we had have followed the Chicago school (or the Harvard school) line – and left it to the private market to sort the mess out. It is clear to me that we were facing a repeat of the Great Depression such was the damage to the financial system and the plunge in real output in the major economies.

Finally, the Australian downturn was less severe than we thought at the time of the intervention. It is easy to look back with the benefit of the 20-20 vision and say that in some areas too stimulus was provided. I am also asked about the price distortions in the trades area where builders and plumbers etc that are working on public infrastructure projects are now reportedly charging increased fees to contract private work. I question the veracity of that claim in fact – given the data doesn’t show any major blowout in labour costs etc.

But the major point is that at the time the stimulus packages were designed and announced, the Government believed we were on the precipice of another Great Depression. The international events demonstrate that the crisis has been very severe. So the government rightly assumed that there would be major idle labour skills available to be brought back into productive work. That was a reasonable assumption and the fact that the downturn hasn’t been as bad as that demonstrates that the fiscal stimulus has been very effective.

However, I also always stress that I would have concentrated the stimulus on efforts to provide public sector jobs to the most disadvantaged workers who bear the brunt of unemployment and underemployment. They are still idle and without sufficient income. It would have delivered much more to the economy than competing for tradespersons with other “private” demands for those services, however, weak they were at the outset of the crisis.

I also remind people of the relativities here. You might like to read this article by Mike Carlton in last Saturday’s Sydney Morning Herald (August 21, 2010) – Worst idea ever? That batty claim was never going to fly .

In his eloquent style, Carlton documents the scandalous purchases of the navy Super Seasprite helicopter by the previous conservative government in Australia. This article is in the context of the Opposition leader Tony Abbott screaming about the waste of the fiscal stimulus packages during the election campaign that has just finished. Carlton says:

Tony Abbott is either a barefaced liar or he has a mind like Swiss cheese. “This is the worst-managed program in living memory, bar none,” he spluttered on Wednesday, banging on again about the government’s roof insulation scheme.

Hardly. That distinction belongs to the Howard government’s grand plan to acquire the Super Seasprite helicopter for the navy, an epic fiasco that blundered along for 12 years and squandered well over $1 billion before it was scrapped.

It is worth reading the full article because it documents the incompetence of the conservatives when they were in government and the scandalous waste that the public purse endured under them while they were cutting back in social policy areas.

Very parochial digression: Lying property developers leave Newcastle alone – for the time being

While on the construction theme, it was announced yesterday that the GPT group has withdrawn its plans to invest $A600 million on the inner city Newcastle development. The company said that the state government was to blame because it would not yet commit to pulling up the rail line that serves this area of the town.

The property developers want the government to rip up the rail (at public expense) and hand over the land to them for their profit. All the conservatives in town with links to the development – that is, stand to benefit in dollars – are aghast at the news.

The local state member who has been pushing the development and promoting fraudulent reports that are being used to give the development plans legitimacy which they do not deserve is now threatening to resign. My advice: tender the resignation immediately and don’t worry about us we will not miss you for one second.

There is a very strong grass roots lobby fighting to save the rail line – Save our Rail – which deserves all the support it can get.

The truth will come out but I suspect that GPT is really struggling with debt as the GFC continues to play out and can no longer risk the development anyway.

In late 2008 I wrote an Op Ed about GPT and the rest of the dirty business just after the Hunter Development Corporation (a local group of pro-market developers and business interests) released a fraudulent report supporting the tearing up of the rail line.

Large property developer GPT recently unveiled a revitalisation plan for Newcastle. It followed up with an advertising blitz and has lobbied major figures around town to engage their support.

It renewed pressure to eliminate the rail into Newcastle. The new Premier is rumoured to be supportive with reports that “public sentiment” now favours scrapping the rail. I wonder where those “reports” originated from.

GPT has also threatened to withdraw should their demands be rejected.

While Newcastle badly needs revitalisation, puerile, “bully-like” threats are no way to engage a community contemplating large changes to its public spaces.

There are also other sources of finance.

While I support initiatives that increase secure well-paid employment opportunities and efficient use of public space, there has been a lack of quality information provided to allow a full appraisal of the costs and benefits of the proposed development.

Plans to revitalise urban centres that have become decaying hulls like Newcastle typically bring growth and employment to the areas where investment is concentrated.

Development will undoubtedly generate employment, at least in the construction phase.

However, the net benefits of the proposal are disputable because GPT’s economic “research” is unsound.

Overall, their retail growth projections are too optimistic given current economic realities. The recent retail spending boom was fuelled by unsustainable

credit growth and the coming recession will force consumers to spend more carefully and contain their debt.

GPT commissioned a report from Callaghan Institute, which despite its formal name doesn’t even have a WWW site. If an undergraduate student had submitted the same analysis to me for examination I would have failed it.

The Report is carefully “selective” in the questions it asks so as to put the GPT proposal in its best light. Such selectivity is unacceptable in public debate. Here a few of many examples from the Report.

First, it estimates that 2,720 jobs will be created if the State Government tears up the rail line after Wickham and extends roads to the harbour. But it fails to examine the alternative of building better access crossings with the line intact which would also generate thousands of jobs.

Second, San Diego is used as an exemplar of the benefits of better harbour and city linkages. But the Report doesn’t mention that San Diego kept the heavy rail line which bisects its city centre and harbour and linked the two using improved crossings; a bike path along the line and light rail extensions to other city locations. San Diego provides a case study for integrating heavy rail into the development proposal.

Third, the Report ignores the “substitution” losses that would arise elsewhere in the region if the plan proceeded. Economic activity has to be supported by a population base which spends. The danger is that Hunter population growth will not be sufficient to sustain the new retail capacity and so the development will compete for spending that underpins retail jobs elsewhere in the region.

Business may be attracted back to the city centre but other Hunter businesses will lose that trade and these losses need to be estimated.

Fourth, the report estimates major jobs growth in construction. The quantum is debatable but, in general, infrastructure projects like this generate lots of work during the building phase. But the size of the estimated construction employment growth is so large relative to the available Hunter construction workforce, that supply will be strained. Building costs will increase throughout the region. These impacts should be estimated.

The other “unstated” reality is that most of the new jobs will be casualised low-paid positions in retail. The development proposal doesn’t provide for inner city residential capacity which is affordable to these “key workers”.

I don’t support a proposal where a relative few high income earners enjoy living close to the beautiful beaches and harbour while being “serviced” by a low income workforce that is “shipped in” each day. All income groups should be able to live close to these assets.

Further, the rail line makes these assets accessible for residents in the hinterland who have no alternative transport, such as Hunter kids.

The Report offers the same flawed analysis used by developers last time they wanted the rail scrapped. While no valid economic case exists to date, there are many cultural, social and equity reasons to keep the rail.

In summary, two things are required before development should proceed. First, better economic estimates of all the costs and benefits are needed. Second, community engagement as to what the public spaces should look like and what transport is provided to access them.

As a dislaimer – I am a relatively regular rail user and live in the area under attack from the developers.

Conclusion

So from the macro to the very local. But if more citizens were as effective as the Save our Rail group and carried the fight to macroeconomic issues, the deficit terrorists would have a harder time of it.

That is enough for today!

This sort of goes similar to my question on yesterday thread.

Yesterday after reading the AFR, I observed that the combined after-tax profit of the big 4 banks was $21 billion. Reflecting on that, considering a great deal of bank profits are fees, reltive to other banking operations around the world.

2.1% of GDP is bank profit, an IMMENSE amount, considering the portion of fees. Market friction in otherwords, it’s just not a healthy position for the economy.

Well you have commented that 1 million workers are in construction. Now current participation rates of approximately 65% mean that there should be around 14.3 million workers in the country, 7% of them in the construction industry. I would also suggest that this level has built up over the decade long hubris of the residential real estate bubble. Equally I would be concerned that this is not healthy.

As far as inacitivty goes, saying that construction workers bearing a larger burden of labour market dislocation in recessions, this refers to yesterdays query. As far as the social impact goes, it is also a high risk industry, in terms of engagement, and their VERY high wages reflect this. If on an individual level they aren’t smoothing their incomes, then we are socialising their loss of income.

How do you propose this market adjust itself, if there is the possibility there has been a misallocation of resrouces to this area to begin with?

Construction labour is a non-tradable, and incredibly militant. I would propose it has a great deal of embedded inefficiencies. I can’t see how an adjustment would take place without a price and/or demand shock.

Hi Bill.

I just discovered your site – thanks for your efforts.

I have one question – off topic but I hope you will answer.

If gov money creation results in net new money, whats the accounting offset in the reserve accounts.

I was discussing this on a housing blog here in Canada and the point came up.

I think the offset must get dumped into the deficit somehow but I’m not clear on how this occurs.

Tim.

Aaron:

Within construction, there’s competition between firms, and between individuals to get/retain jobs, and fairly rapid turnover. So I don’t think you can claim inefficiencies at the micro level. The question is whether the sector as a whole is too large.

But construction is inherently highly cyclical. It’s the derivative, the rate of change, of the housing stock, so modest changes in the demand for housing will be greatly magnified in terms of new construction. So which is more inefficient — direct counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus towards construction to support it through the lean times, or allow the sector as a whole to contract and then re-expand with every business cycle. The latter involves dissipating a lot of productive capacity (skilled workers, firm-level organization, etc) that will have to be rebuilt once private construction recovers.

Maybe the recent boom is an all-time high, and construction won’t return to that level even when the economy fully recovers. In that case, you could argue that there is some mis-allocation in trying to support it at that level. I would argue that that’s unknowable; but it’s almost certain that private construction demand is below what it will be in the future, so some public support is almost certainly a good capacity-preserving idea.

And all that is beside the main point in an overall recession of deficient aggregate demand — construction workers, who would otherwise be unemployed, will be earning and spending wages, thus supporting manufacturers and retailers and service providers and everyone else. In terms of the power (multiplier) of various stimulus options, direct spending on infrastructure construction is one of the best (though to some extent it’s limited in speed and scope).

Hi Bill.

One more question.

One of the takeaways I got from your stuff is that in MMT money creation is by fiat and that Bond sales are not necessary – in fact used just (or mostly) to manage reserves.

Levy has just put out a piece here,

http://www.levyforecast.com/recent-publications/docs/Widespread%20Fear%20of%20the%20Wrong%20Kind%20of%20Price%20Instability.pdf

Chart 6 and chart 7 in the piece show Gov net expenditures as % of GDP and Gov net borrowing as % GDP over the last 50 years.

Problem is change the change in net borrowing in the period 2000-2010 is about twice the change in net spending.

Why the huge amount of borrowing if its only needed to manage reserves?

Have I misunderstood?

Thanks.

Tim.

I assume the fiscal stimulus was with debt.

I’d like to know if Australia didn’t need as big a stimulus package because its trade deficit was smaller, especially with china.

A little off-topic but …

The way most economies are set up now, is all NEW (emphasizing NEW) money debt, whether private or gov’t?

Thanks Lilev,

“Within construction, there’s competition between firms, and between individuals to get/retain jobs, and fairly rapid turnover. So I don’t think you can claim inefficiencies at the micro level.”

There isn’t competition to get/retain jobs when the government throws up infrastructure projects as counter-cyclical fiscal policy.

“The question is whether the sector as a whole is too large.

But construction is inherently highly cyclical.”

Correct, and the risk associated witht he cyclical nature, as I said, is reflected in their pay, to compensate for times when they are unemployed. It is their responsibility to smooth their income over this cycle, which I also mentioned.

“It’s the derivative, the rate of change, of the housing stock, so modest changes in the demand for housing will be greatly magnified in terms of new construction.”

That’s a statement, not an argument.

I’m attempting to ascertain why it is perceived here as such a bad thing that construction workers endure unemployment when their very own remuneration structures, and their access to policy makers via trade unions, contribute to the cyclical nature of their industry.

As far as I see it, they have received 12-14 years income in the last 8 years. They can always stack shelves at Woolworths or cook fries at MacDonalds until the next construction project comes along if you’re worried about lack of output.

“So which is more inefficient – direct counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus towards construction to support it through the lean times, or allow the sector as a whole to contract and then re-expand with every business cycle.”

Supporting the industry in a counter-cycle is much more inefficient over the long term. The industry prices itself incorrectly, and it gets away with it because of labour restrictions it imposes on new entrants, by conducting anti-competitive behaviour by coercing supplier behaviour, particuarly to non-union participants, and well as having captive customers because it is a non-tradable sector. One can then add further about the gratuity they receive from the political process, the new train line in Perth for the CFMEU is a prime example.

As long as policy after policy keeps being enacted the support their improper behaviour, there is no reason for them to change. A price or demand shock that puts downward pressure on prices is a good method to adjust improper behaviour.

“The latter involves dissipating a lot of productive capacity (skilled workers, firm-level organization, etc) that will have to be rebuilt once private construction recovers.”

A cost which is embedded in their remuneration.

“Maybe the recent boom is an all-time high, and construction won’t return to that level even when the economy fully recovers. In that case, you could argue that there is some mis-allocation in trying to support it at that level. I would argue that that’s unknowable;”

I would say there are market forces that are able to react more quickly to find the proper clearance price however. That is my fault with government, not that they are inefficient, it’s just they are horrible at pricing. The fact the are not revenue constrained may play a part in that.

“but it’s almost certain that private construction demand is below what it will be in the future, so some public support is almost certainly a good capacity-preserving idea.”

Why?

I personally have a desire to demand private construction, I just refuse to demand it at the curernt price. Supporting the current price, from a personal perspective, is unwanted. I would argue that the current price levels are unwanted by many, to a point they are detrimental to the entire economy, due to the inelasticity of demand for shelter.

To opt out of consuming housing, to demand and apply downward price pressure, is homelessness. It’s an implausible response, and only leads to aggregate demand being withdrawn from other areas, typically consumer discretionary spending.

“And all that is beside the main point in an overall recession of deficient aggregate demand – construction workers, who would otherwise be unemployed, will be earning and spending wages, thus supporting manufacturers and retailers and service providers and everyone else. In terms of the power (multiplier) of various stimulus options, direct spending on infrastructure construction is one of the best (though to some extent it’s limited in speed and scope).”

I understand the mechanics of supporting aggregate demand, I’ve got that bit from MMT.

I’m trying to ascertain where within this framework can an adjustment of a misallocation of resources take place without a price or demand shock. When customers are as captive to vendors, as they are with construction in Australia, ‘competition’ for me just doesn’t satisfy as a solution.

Bill Said: Monetary policy has been proven – categorically – to be ineffective in dealing with aggregate demand failures of the sort we have witnessed in the current crisis.

Yes but it stoped a huge number of businesses going bust, interest rate drops saved the business day.

Bill Said :Overall, their retail growth projections are too optimistic given current economic realities. The recent retail spending boom was fuelled by unsustainable credit growth and the coming recession will force consumers to spend more carefully and contain their debt.

OK Bill you cant get away with “COMING RECESSION” without some data to back it up, this site is macro impirical you know.

As for GPTs push to get rid of the rail line I am surprised this is still going on. A Government cant be serious about Global Warming and get rid of rail that will put more cars and trucks onto to road.

GPT will act in GPTs interests and the local population come a long way last. Your point that retail spending will not increase it just gets relocated from existing retailers to the new centre is a description of how Retail development “builds” across the whole of Australia.

Aaron says:

Thursday, August 26, 2010 at 10:32

As far as I see it, they have received 12-14 years income in the last 8 years. They can always stack shelves at Woolworths or cook fries at MacDonalds until the next construction project comes along if you’re worried about lack of output.

Aaron we allready have great people working at MacDonalds and doing nightfills at Woolworths. The construction workers you refer to are hard working Australians not some thing for you to move arround to profit your purse. The Job Guarantee would be perfect for the construction industry as it would maintain a pool of skilled workers to fill the ebb and flow of construction work. I propose an industry specific JG scheame for Construction Workers.

Greetings Punchy,

“Aaron we allready have great people working at MacDonalds and doing nightfills at Woolworths.”

Yet it appears an insufficient number of great working people as there still appears to be vacancies available for them. My indication is that an unemployed construction work need not be inert or idle labour if construction activity in diminished. There is other productive outlets they can pursue until another construction project commences.

“The construction workers you refer to are hard working Australians not some thing for you to move arround to profit your purse.”

It’d be better for the purpose of debate if you didn’t ladden your comments with emotive virtues. Virtually every Australian is hard working, and it’s counter productive for debate to attempt to elevate construction workers above the rest of us because of their ‘hard working’ virtue.

As far as ‘profitting my purse’, I am of the opinion that construction labour has gauged the economy for nearly a decade, their ‘purse has profitted’ at a terrible social cost, and not it appears that this extraordinary profit is now embedded as an expectation, or even entitlement. I am seeking a revaluation to a fair price, I am not looking to extract rents from their labour.

“The Job Guarantee would be perfect for the construction industry as it would maintain a pool of skilled workers to fill the ebb and flow of construction work. I propose an industry specific JG scheame for Construction Workers.”

Why have a government operated job scheme where these guys are on the JG (i.e. minimum) wage. It’d be just as valid to have them work in the private sector for the JG wage. Construction activity would pick up over night if these cost savings were passed onto consumers.

I would warrant they could be a fair deal above the JG wage and still have sufficient construction activity. But a decade long era of unaffordably high wages could only be offered by debt-fueld, speculative buying. That era has ended, thus so should the unaffordably high wages, though the behaviourable aspects might be difficult to overcome, as I mentioned with expectation/entitlement.

Maintaining these wages with a stimulus program doesn’t appear to offer downward pressure on these prices.

Thanks for the reply. I do get emotional about the lack respect our world shows to thoes who are not blessed with perfect memories that enable them to pass exams devised by acedemics. It is an illusion that the banker should be paid more. In fact the toilet cleaner may claim a higher wage on the basis that the job is less attractive than being a banker. Construction workers work in a dangerous enviroment and have been under payed. It is the elite class of Bankers and so called proffessionals who have been over payed for 20 years. The construction workers are just catching up.

I agree bankers are immensely over-paid, I view banking as a utility not an enterprise.

However, I disagree about construction workers being underpaid, they are the new rich of modern day Australia. The most recent ABS figures on submitted incomes was that the top 3% of income earners have a taxable income of approx $143,000 or more. Virtually every qualified tradesman earns at least that much through personal extertion. The distribution stuctures available to them, via subcontracting and family trusts disguise much of it. Structures not readily available to people such as high level public servants for example.

So I will assert that not only have they caught up, the sector has extracted more than their fair share of national income and have done so for over a decade.

It is the workers in retail and hospitality sectors than are feeling the brunt of undisclosed inflation in my opinion.

Aaron. Thanks again. Will have a think about what you say. I agree with your comment about Retail and Hospitality. In regard to tax structures I think the number of negative geared tax payers may sugest it is the prefered method. Negative Gearing is a bit of a sleeper as it could cause a mass exit from property if the property bubble bursts.

Tim (26th Aug, 4:54) asks a good question: “Why the huge amount of borrowing if it’s only needed to manage reserves?” I assume Fed Up (subsequent post) is answering this when Fed Up says “I assume the fiscal stimulus was with debt.”

If Fed Up is saying that much of the borrowing is due to traditional Keynsian “borrow and spend” policy, then I agree. Plus this “borrow” policy is stark staring bonkers, for the following reason.

There is no point whatever in government borrowing something (i.e. money) which government can create in limitless quantities anytime. I.e. MMT’s founding father, Abba Lerner, was right: where stimulus is needed, government should just print and spend, rather than borrow and spend. Incidentally Keynes and Milton Friedman were well aware of this “print and spend” option.

IN CONTRAST, where government wants to expand the public sector relative to the private sector where an economy is at capacity, and government wants to borrow rather than raise taxes (which is invariably explained by politicians’ political cowardice!), then borrowing DOES make sense. That is, government HAS to damp down the private sector (e.g. by borrowing) so as to make room for public sector expansion.

Ralph,

You sure about that. If the government ‘borrows’ it is doing nothing other than swapping, say, £100 of one asset for £100 of another. There is no reduction in spending capacity in the private sector.

My understanding of MMT was that only taxation could dampen transactions because that is the only thing that creates drag and destroys money (although I suppose increasing capital requirements at private sector banks would limit the amount they can expand money).

Tim, couple of things on your question relating to the Levy charts…..what you’re seeing in Ch6 is one half of the automatic stabiliser effect (expenditure…..and note that the timframe is really from 2008 onward). Of course there is stimulus in there as well, but the rise is explained in general by increases in welfare payments and other disbursements. What you don’t see in the chart is the flipside – the large fall in revenues (less taxes and other levies). They have fallen precipitously, and the (increasing) difference between the two explains the increase in borrowing (as per Ch7).

But that’s where it gets interesting. While the government doesn’t necessarily have to issue bonds as you note, the fact is, it still does. And while it is intrinsically a monetary (reserve) operation, the sad fact is that the governments themselves don’t even begin to think of it in this way. All they think they are doing is “match-funding” the deficit. That’s actually what they think. It’s not that they are keeping any secrets. They simply don’t see the reserve operation for what it is. That’s why you hear the Aussie politicians on the election trail banging on about “costing” for expenditure measures (ie. what they are going to save on the other hand in order to make any given expenditure “revenue neutral”), and why other deficit hawks continue to bang on about unsustainability of deficits.

Neil, my understanding is that taxation is the most powerful tool to dampen demand. But trade deficits, and as you say, capital requirements, can do it too. If a government can increase private saving, as by hiring Little Orphan Annie and Bugs Bunny to sell war bonds in WWII- a case where Ralph’s IN CONTRAST paragraph applied, that can have the same effect.