I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Iceland … another neo-liberal casualty

What do you do when your government is selling you out? Get the titular head (president) to intervene. That is what seems to be happening in Iceland at the moment. While the president is being accused of being an old political hack who longs to be back in the limelight, the more accurate interpretation is that he is reflecting the mood of the population which have been abandoned by a government intent on big-noting itself on the world stage by pushing for EMU admission. The sources of the problems in Iceland mirror those that have been at work globally to undermine the stability of the financial system and plunge real economies into deep recession – a religious belief in the efficacy of unregulated markets and the efficiency of entrepreneurial zeal. Both beliefs are now in shatters along with many economies not the least being Iceland. It is time that Iceland invoked its status as a modern monetary economy whose government has sovereign status in its own currency and started showing leadership to advance public purpose.

Yesterday, the President of Iceland vetoed an act of parliament which would have seen the nation “repay” £3.4bn to Britain and the Netherlands. This repayment was in relation to the amount that the British and Dutch governments paid out in 2008 to their citizens who had deposits in a private Icelandic bank which collapsed during the height of the global financial crisis.

While the jingoistic British press is making all sorts of threats against their tiny northern neighbour, the mood in Iceland is very sour. They have not yet forgiven the British government for using the UK anti-terrorist act to freeze all Icelandic assets in the UK in late 2008. It was that move that was the final nail in the Icelandic banks’ solvency.

The Icelandic population think the deal their parliament has agreed to is not in their interests and not their responsibility and they realise that the motivation of Iceland’s politicial leaders is really to walk the EMU stage, which the overwhelming proportion of the population are opposed to.

The reality is that the Dutch and British governments bailed their own citizens out after they allowed Icesave to operate under the Passport system.

They then tried to cadge the money back from the Icelandic government – there were claims that under European law there is a sovereign guarantee of deposits (that is unclear – there is no requirement of a state guarantee). Further, they claim Iceland is being discriminatory (against European law) in that it bailed its own citizens out but refused to bail out the foreigners (also unclear). The Dutch and the Brits will not go to an independent court to let these matters be decided impartially. The reason – they would probably lose their bullying capacity to pressure Iceland to pay up.

The problem for Iceland’s citizens, is that the Icelandic Parliament, seemingly wanting to appease those who would block its proposed entry into the EMU (Britain has been making threats), finally agreed to repay the loans. You can read more about what the people think via the In Defence home page.

It is clear that the citizens did not approve of this deal and the vast majority do not want to go over to the Euro (that is, enter the EMU). This people protest which has gathered strength in 2009 is behind the president’s move yesterday. It is only the second time in the 66-year history of Iceland as a republic that the titular head has exercised this power.

The president’s made his decision public via a TV address to the nation. His official declaration said that after the parliament passed the law to repay the loan he:

… has received a petition, signed by about a quarter of the electorate, calling for the Act to be subjected to a referendum. This is a far larger proportion of the electorate than the criterion that has been referred to in declarations and proposals from the political parties.

Public opinion polls indicate that the overwhelming majority of the nation is of the same opinion. In addition, declarations made in the Althingi and appeals that the President has received from individual Members of Parliament indicate that the majority of the Members are in

favour of holding such a referendum …It is the cornerstone of the constitutional structure of the Republic of Iceland that the people are the supreme judge of the validity of the law …

Now the people have the power and the responsibility in their hands.

Go Prez!

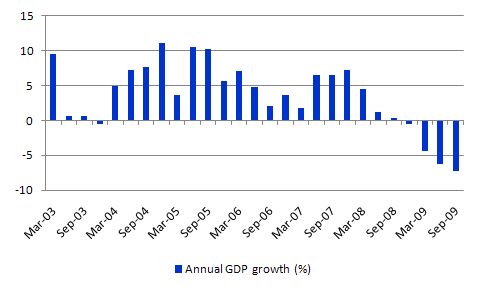

The following graphs show why the people and their president are taking a stand. The data is from Statistics Iceland and the first graph is the annualised real GDP growth rates from 2003 to third quarter 2009. The collapse in their income generation is very substantial and will take then some years to recover from this shock.

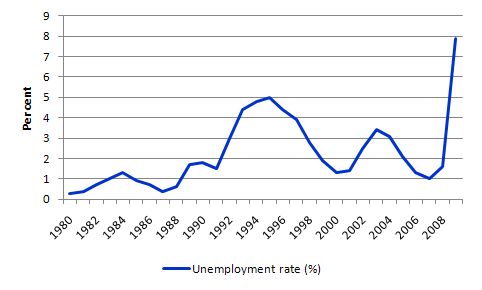

The analogue of the real output collapse is, of-course, the labour market impacts. The next graph shows the annual unemployment rate in percent. The current rise in unprecedented in Iceland’s history and will foment social instability unless it is dealt with as a matter of urgency.

Briefly

The Guardian Newspaper has a neat summary Timeline of the events relating to this saga.

Landsbanki was established by the Icelandic government as a national development strategy in the C19th. It was a retail savings operation intially and later became the central bank (1927-1961) but lost that role when the Central Bank of Iceland was created.

With the neo-liberal era starting to dominate it began to engage in more wholesale and speculative types of financial transactions in the 1980s and was corporatised (1997) then fully-privatised in 2004. At this point it had developed a considerable international exposure.

All this was done under the watch of a conservative government which was tossed out at the last election as the electorate realised their neo-liberal ideology had brought their nation unstuck.

The finance editor for the conservative Times newspaper said that Britain and Iceland failed to acknowledge warning signs over collapse. He said that:

The origins of this problem go back to the early 1990s when Iceland embarked on its Arctic version of Thatcherism – privatising its state-owned banks and deregulating them at the same time. Liberated from state control, the banks were soon seized by a small band of energetic local entrepreneurs who then started an aggressive expansion drive.

Icebank “was established in 1986 by the savings banks in Iceland”. In 2006, Icebank’s owners “agreed on a new strategic vision for the Bank. This was considered necessary because of the fundamental changes occurring in the Icelandic banking sector, not least the rapid and successful overseas expansion of the bigger Icelandic banks and the continuous growth of the larger savings banks, which has made them more and more willing to act on their own rather than require the services of Icebank.”

So Icesave was an international spinoff for Landsbanki and conducted its deposit-taking business on-line attracting a mountain of business by offering interest rate guarantees that would pay returns above the local rates in Britain and the Netherlands. It only operated in the latter country however for 5 months in 2008 before closure.

Previously the Icelandic banking system was very conservative working within the local depositer base and lending to home buyers and local business.

With the neo-liberal abandonment of proper financial oversight the privatised banks went crazy. They started to tap into the global wholesale markets and borrowed billions. They also developed the overseas retail operations like Icesave.

They then loaned huge sums to the newly emergent global entrepreneurial class in Iceland, imbued with the same free-market rhetoric that has brought the world to its knees. They engaged in a vigorous foreign asset acquisition program – buying incidentally a lot of British business assets. Most of this spending has collapsed in value.

So much for the claims that the financial markets know anything about optimal resource allocation.

Then the problems came courtesy of the US sub-prime collapse. In the first 9 months of 2008 the Icelandic króna depreciated dramatically (over 35 per cent) and this put pressure on the private banks in Iceland who were very highly leveraged in foreign currencies. The global financial crisis made it very hard to refinance their commitments.

Banks runs started as speculation mounted that they would collapse. On October 6, 2008, the Icelandic government issued this statement:

The Government of Iceland underlines that deposits in domestic commercial and savings banks and their branches in Iceland will be fully covered. “Deposit” refers to all deposits by general customers and companies which are covered by the Deposit Division of the Depositors’ and Investors’ Guarantee Fund.

Note domestic! At this point, overseas subsidiaries of Landsbanki went into administration and the Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authority (FME), which oversees prudential control of the financial system there, put Landsbanki into receivership – effectively nationalising it.

They reasserted that all domestic deposits would be guaranteed. Icesave at this point effectively froze all business and collapsed.

Another interesting point is that Icesave did not operate in Britain or the Netherlands under the oversight of the financial regulator in each country. That is is was outside the oversight of the FSA. Instead it operated under the so-called “Passport scheme” which allows banks from the European Economic Area to fall back to their own country-of-origin compensation policies if there is a failure. But there is no requirement that the government in the country-of-origin is obliged in any way to honour the private debts.

What happened with Icesave was that when the Icelandic government nationalised Landsbank, its holding company they announced they would not recognises the Passport agreement which then denied the UK and Dutch depositors protection.

But there is seemingly no requirement that the depositors bailout is a state obligation. That is one of the arguments that the debate in Iceland is emphasising. This was a private bank pursuing profit for its shareholders. The only moral obligation to redress the folly of its business decisions lies with the management of the company and its owners.

The Icelandic government has no moral obligation in my view (nor legal obligation it seems) to bailout a private company to advance the welfare of foreign citizens.

For the British Treasury and the Financial Services Authority to allow their citizens to be so exposed is really a failure on their behalf and there is a strong case that the bailout they initiated as part of this loan arrangement with the Icelandic government should end there – with the British government holding the can. The same can be said for the Dutch government.

The Times finance editor concurs on this point:

In Britain, regulators were complacent, doing nothing to curb the ambitions of banks over whom they had no supervisory power. They saw the Icelandic Government guarantee and wantonly failed to look beyond it. They failed to see that it was hopelessly threadbare when the banks’ liabilities were the equivalent of ten times Iceland’s annual output.

While ordinary savers could be forgiven for failing to see the warning signs, professional investors such as council treasurers were negligent. With the Icelandic krone in freefall there was every reason for caution.

What are the consequences?

The only thing the Icelandic government should worry about is whether public purpose is being achieved by its actions. Given the economic situation they should be doing nothing that will undermine the capacity of the economy to recover and start reversing the job loss.

Apparently, the “The annual interest alone, if adjusted for population size, would be the equivalent of the UK paying over £40bn a year, almost half the cost of the NHS”. (Source).

Further, the payment to Britain alone of £2.4 billion over 15 years (any outstanding amounts are nullified in 2024) is chicken-feed in terms of the overall British government deficit. But for Iceland it equals 40 per cent of its GDP (or £11,000 per person).

The problem is that the alleged debt is not in kronor. So given it is a foreign currency, it represents a real impost on the standards of living for Icelandic citizens and will reduce the government’s capacity to lead the economic back into recovery. It will have to sacrifice large chunks of its export revenue and cut back imports severely to service a loan like this in a foreign currency.

If it really wanted to repay the loan, the best of the worst options would be to tell the foreign governments that they will be paying back in kronor. There is clearly no risk of insolvency then. However, the British and Dutch governments would never accept this option.

In that sense, I would ignore the threats coming from the external voices and hope that the people reject the payment in the referendum that has to now be held.

However, if you believe the British, then the consequences for Iceland are dire. The Times quoted Lord Myners, the British financial services minister as saying that “Iceland risked pariah status if voters said “no” to the package”. He was quoted as saying:

The UK Government stepped in to ensure that all retail depositors with Icesave were fully paid out, and now we expect the Icelandic Government to ensure that we are repaid that amount which Iceland owes us.

This was couched in terms of the threats that Britain and the Dutch government (not too mention other European governments) would stop the IMF lending any more funds to Iceland (that is, a second tranche) and also would block its application to enter the EMU.

A common claim (for example) in relation to the IMF is that Iceland is obliged to repay the loan because “settling the compensation row was part of the deal it made with the International Monetary Fund when it got a bail-out from the scheme in the wake of its financial collapse.”

That doesn’t seem to be the case. Reuters reported today that the IMF released a press release late yesterday and said that “the Icesave bank compensation deal was not a condition of Iceland’s IMF loan program as long as other lenders continued to finance part of the $10 billion program.” I couldn’t find the official release on the IMF press pages.

Meanwhile Fitch, one of the rogue credit rating agencies, announced it was downgrading Iceland’s sovereign ratings to around “junk status”.

Ever trying to maintain is self-importance, Fitch said in their press release that:

Today’s decision by Iceland’s president to refer the Icesave agreement to a referendum creates a renewed wave of domestic political, economic and financial uncertainty. It also represents a significant setback to Iceland’s efforts to restore normal financial relations with the rest of the world.

Further, ever interested in democracy (that is, the citizens of Iceland having some say in what their government commits them to), the Fitch spokesperson said the decision to force a referendum:

… creates a wave of domestic political, economic and financial uncertainty. It also represents a setback to Iceland’s efforts to restore normal financial relations with the rest of the world.

The credit rating agencies should just be ignored. Please read my blogs – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates – Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies – for more discussion on this point.

Argentina

For a real world example of the benefits of adopting a floating, sovereign, currency we can look to Argentina.

The crisis was engendered by faulty (neo-liberal policy) in the 1990s. Between 1991 and 2002, Argentina essentially adopted a currency board by pegging the Argentine peso to the US dollar for reasons that beg belief. This faulty policy decision ultimately led to a social and economic crisis that could not be resolved while it maintained the currency board.

However, as soon as Argentina abandoned the currency board, it met the first conditions for gaining policy independence: its exchange rate was no longer tied to the dollar’s performance; its fiscal policy was no longer held hostage to the quantity of dollars the government could accumulate; and its domestic interest rate came under control of its central bank.

At the time of the 2001 crisis, the government realised it had to adopt a domestically-oriented growth strategy. One of the first policy initiatives taken by newly elected President Kirchner was a massive job creation program that guaranteed employment for poor heads of households. Within four months, the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar (Head of Households Plan) had created jobs for 2 million participants which was around 13 per cent of the labour force. This not only helped to quell social unrest by providing income to Argentina’s poorest families, but it also put the economy on the road to recovery.

Conservative estimates of the multiplier effect of the increased spending by Jefes workers are that it added a boost of more than 2.5 per cent of GDP. In addition, the program provided needed services and new public infrastructure that encouraged additional private sector spending. Without the flexibility provided by a sovereign, floating, currency, the government would not have been able to promise such a job guarantee.

Argentina demonstrated something that the World’s financial masters didn’t want anyone to know about. That a country with huge foreign debt obligations can default successfully and enjoy renewed fortune based on domestic employment growth strategies and more inclusive welfare policies without an IMF austerity program being needed. And then as growth resumes, renewed FDI floods in.

One commentator wrote a few years ago that that the Argentinian Government appears to have perpetuated the perfect crime. The Government offered the world financial markets a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ settlment which was favourable to the local economy. At the time, the rhetoric claimed that countries that treat foreign creditors so badly would surely stagnate and suffer a FDI boycott.

This is the standard neo-liberal line that is used to coerce debtor nations into compliance with the needs of ‘first-world’ capital largely defined through the aegis of the IMF. But the Argentinean case shows this paradigm to be toothless because the Government defied the major players including the IMF and the Argentine economy went on to boom despite it.

It is clear that prior to the current crisis many foreign firms started moving back into Argentina in addition to strong investment from Argentine interests. The country’s biggest real estate developer explained (in 2005) the quandary facing the neo-liberals as such: “there has never been a better time to invest in Argentina … [as for foreign banks, after shunning Argentina for a while] … now the banks are coming to us … It’s been tough. We will have restrictions … But in terms of access to capital, what defines access? Greed. When opportunities look profitable, access to capital will be easy.”

This is a lesson all countries should learn. International capitalism, ultimately does not really take ‘political’ decisions – it just pursues return.

The clear lesson is that sovereign governments are not necessarily at the hostage of global financial markets. They can steer a strong recovery path based on domestically-orientated policies – such as the introduction of a Job Guarantee – which directly benefit the population by insulating the most disadvantaged workers from the devastation that recession brings.

Argentina’s defiance has lessons for Iceland. The financial community will not stay away for long. As soon as there are prospects for profit the investors will be back to chase return. The neo-liberal threats are just myths once we realise that in capitalism ‘greed comes before prejudice’.

Conclusion

When I initially read (in August 2009) that Icelandic Government was agreeing to pay the UK and Dutch governments nearly 4 billion euros for the failed Landsbanki which had branches in their countries and lost billions I was amazed that it would be so stupid.

Especially when the bank was privatised under the neo-liberal rush to obliterate public activity and developed very high international exposure. It went broke which many of these unregulated gold-seekers have done.

I just cannot work out why this is a problem for the sovereign government of Iceland … they are sovereign in their own currency – the kronor and they do not have to join the EMU nor borrow from the IMF.

I have a one word solution to the threats that they will be excluded from the world financial system – Argentina – a.k.a default. If push-comes-to-shove I would default on all publicly-held foreign currency loans.

While the government seems to think that by joining the EMU they will be “shock-proofed” they should just look at Greece and soon Spain and Portugal. Joining the EMU would be the last thing the tiny island should do.

The overwhelming majority of Icelandic voters seem agree with me on that.

That is enough for today!

While I agree to a certain extent that the neo-liberal policies led to Asian Financial crisis, Argentina’s currency crisis and the current crises that is affecting many countries including Iceland.

But one also has to blame individual countries which agreed on implementing such policies. During the Asian Financial crisis while Indonesia and Thailand faced terrible problems, Malaysia and South Korea was not as badly affected. Also Australia, France have managed the current crisis better than say Iceland, US and UK. Therefore placing the blame entirely on UK or USA for Iceland’s debacle may not be totally fair.

Would you blame Australia that Pakistan lost in the cricket test match ? It is Pakistan who could not lift their game and ended up losing. Similarly UK(govt) cannot be completely blamed for Iceland’s debacle. Prior to the crisis Iceland was one of the fastest growing economies in the world and at that time they may have benefited from adhering to the policies dictated by UK or USA. But no one stopped them from being pragmatic by anticipating that there might be risks involved in blindly following what was dictated to them by UK.

There are always different points of view in any aspect of life including economics(and with the advent of internet more and more people like you are almost costlessly pointing out some of the limitations of the dominant school of economics thought). If people or countries follow a wrong ideology they must be game enough to share the blame.

Dear Sriram

I agree with you that Iceland is to blame for its own policies which included the conservative government’s embrace of neo-liberal myths that financial markets would self-regulate effectively. There is no doubt that they are responsible for relaxing local oversight. That is why it was appropriate that the government bailed out its own citizens with a deposit guarantee when the consequences of that folly were revealed in October 2008.

But I don’t think they are responsible for the problems the Icelandic registered banks caused elsewhere. In those other jurisdictions it was up to the prudential regulators (FSA) and Dutch equivalents to ensure they were happy to allow these subsidiaries to trade within their shores. Both the British and Dutch governments deregulated financial services dramatically in the 1990s and it was the laxity that that deregulation introduced which allowed this sort of mess to develop. In the case of the Dutch its regulation is sector-based with de Nederlandsche Bank (DNB – its central bank) overseeing banking; the Pensioen en Verzekeringskamer (PVK), overseeing insurance and pensions; and the Autoriteit Financiële Markten (AFM) overseeing share markets. In the UK it was the Financial Services Authority (FSA) and The Treasury that were responsible.

It is only appropriate in my view that those organisations carry the responsibility for not checking up what a Passport entry into the banking system meant – that is, who was ultimately responsible.

best wishes

bill

ps While I was surprised that Australia came back from nowhere yesterday to win the Test match against Pakistan I doubt that the example is analogous. Australia no longer provides the umpires since the rule was introduced that neutral umpires (that is, umpires from non-playing nations) had to be used. Interestingly, part of the pressure to change that rule was due to the empirical observation that Pakistani umpires rarely gave an LBW decision against their own players during games in Pakistan (when you could still play there) whereas the distribution of LBW decisions against foreign batsmen by Pakistani umpires in Pakistan was slightly higher than elsewhere!

Bill,

Could you possibly suggest a good undergrad introduction to accounting?

Very much enjoying the challenging ideas here. Feel like I need to be schooled on the basics somewhat.

Thanks.

Dear Vimothy

Almost any of the introductory texts in accounting will teach you the basics of double-entry bookkeeping. But they won’t teach you anything about the national accounts or the sectoral balances in macroeconomics. Some of my earlier blogs will help you there.

It is good that you are getting some value from my work.

best wishes

bill

Good point on accounting texts, Bill. Even the bank management texts won’t teach you much double-entry accounting for banks, unfortunately.

Thanks for the response bill. So something like this — http://www.amazon.co.uk/Business-Accounts-Accounting-Finance-David/dp/1872962637/ref=sr_1_7?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1262806274&sr=1-7 — would cover the double entry bookkeeping side, but something else is needed for the national account and sectoral balances side. Do you have any suggestions? Believe it or not, I have been devouring your blog in the last few days. It is very shocking to me, since my prior exposure to macro is so conventional, and since its logical consistency makes me feel, given my lack of familiarity, slightly embarrassed. But anyway, I would like to see a reference work where I have things on paper (traditional like that) and get an overview from first principles, if you can suggest something appropriate.

Regards.

Dear Scott

That is true. But if you get the basic concept of what to do if it is a liability and/or asset then you are on the road to getting the bank accounting correct I think.

Perhaps we need a blog on bank accounting although it would be boring to write.

best wishes

bill

Dear Vimothy

The book at the link you provide would probably do the trick although it seems expensive. If you go to the second-hand bookshop at any university or tech school you should pick up a basic accounting book for a very low price. Accounting for dummies (no implication implied!) is also probably okay and usually quite cheap relative to standard text books.

On national income accounting etc, while I don’t want to push my own book onto you (Elgar publishing is expensive) we cover a lot of the stuff in Chapter 8 in a traditional academic manner – http://www.e-elgar.co.uk/Bookentry_Main.lasso?id=1188

best wishes

bill

Thanks. Unfortunately, your book is beyond my budget, but I will grab a second hand intro to accounting, and continue to work my way through your blog.

Regards.

Bill,

I did not mean that it was due to the Umpires that Australia won. My point was that the winning team should not be held responsible(or blamed) for the loss of the losing team.

You mention that:

“Both the British and Dutch governments deregulated financial services dramatically in the 1990s and it was the laxity that that deregulation introduced which allowed this sort of mess to develop.”

Was the Iceland govt not aware of the deregulation in the 90’s. They had atleast 10 years to decide about the implications of this deregulation. Also in economics there is no way that anyone can know all possible future states of nature. So, there will always be decision ex-ante that may appear wrong ex-post(due to Knightian uncertainty). It is possible that Iceland were not as risk-averse as say Australia, hence they did not think that a major catastrophe is around the corner.

In a real world the rules of a game is bound to change(unlike chess) due to uncertainty, and so some decisions that turns out to be wrong ex-post are unavoidable.

Cheers,

Sriram

PS:Empirically Pakistani and Australian umpires(and some Indian and Sri Lankan umpires too) were the most notorious in the past. For a long time India did not win test-matches in Australia. Last year India(also SA won the test series against Australia for the first time after 1990) defeated Australia in Perth because of neutral umpires. India also had a good chances in Sydney test but for the lousy umpiring of Bucknor(also tecnology was not used when there were doubts about the decision).

The moral of story is play fair and hard if you want to win. But if the institutions(local umpires) do not allow a fair play then change the institutions or the rules of the game to win, because if u don’t change the rules others will.

I have a hard time understanding why Iceland taxpayers should be obligated in any way to pay Britain anything.

Far as I can tell, it was a private bank with a private insurance account for depositors.

None of it appears to touch the sovereign until Brown steps in and pays the Brit depositors who were commanding a higher-than- market return, but not expecting higher- than-market risks.

Then he says it is the Icelandic government that owes him.

When financial deregulation comes around and bites the people in the ass with unsoundness and instability, why do the sovereign governments step in and obligate the taxpayers with the downside financial burdens.

I say leave Mr. Brown out there wagging in the wind.

He was Chancellor of Exch. during a lot of the deregulation.

He should have seen it coming.

Sriram,

I do not understand why Iceland’s citizens should be responsible for bailing out British and Dutch citizens. It is plain from the article that Iceland’s citizens are not responsible for setting government policy. If they were, there would be nothing for the president to veto!

Cheers,

Jeff

I agree with Bill’s analysis. It is a question of sovereignty. If Britain and The Netherlands wish to be respected as sovereign nations, then they must accept final responsibility for the socio-economic consequences of private financial activity that occurs within their borders. They issued the stamps Icesave’s financial “passport”, they must deal with the consequences of that decision, not Iceland.

Iceland will of course suffer as a consequence of failed neo-liberal policies reflected in their laws and (lack-of) regulations, but if we are to accept the idea of national sovereignty, then it is disingenuous to assert that the people of Iceland are in any way responsible for the activities of Icelandic registered banks abroad.

Dear Sriram

That is not what I thought you meant either. I was just suggesting the cricket analogy was astray. The only way you could make the analogy work is by thinking of the teams (Australia and Pakistan this time) as the banks and the umpires as the regulators. But unless you want to impute dishonest or incompetent motives it is hard to think that the umpires influenced yesterday’s result. Whereas in the Icesave case, the British regulators for one, failed badly and they should be held to account for the losses of British citizens.

Like everywhere, Iceland was caught up in the neo-liberal imbrolgio – blind leading the blind. The vulnerability was emerging while the mainstream commentary was in denial. I am unsure whether a nation can be more or less risk averse. Australia escaped by the skin of its teeth – the banks would have become insolvent within weeks if the Australian government hadn’t have provided them with a loan guarantee which allowed them to access refinancing funds. Further, the fiscal reaction here was very strong and early which is another major reason why our economy avoided the worst of it. The fiscal response of most governments was tardy and inadequate which is down in not small order to their obsession with monetary policy.

best wishes

bill

Ps thanks for the cricket stats interpretation. I had always thought that the sub-continent had the worst reputation for home side favouritism before the neutral umpiring system came in. I think we would need to do a more detailed statistical study to confirm your assertion that India and South Africa started winning here because of the neutral umpiring system. I would doubt that but if you have data we can analyse it.

Interesting article from Michael Wolf of Financial Times (January 5 2010) on the late joining Euro minnows being forced into perpetual recession due to the EMU rules. That Iceland’s goverment wants to join the EMU by paying an extortionate admission fee for the benefit of joining these countries in the trap where “they cannot readily generate an external surplus; they cannot easily restart private sector borrowing; and they cannot easily sustain present fiscal deficits” beggars belief.

Jeff65,

I also do not think that people of Iceland are responsible for the mess they find themselves to be in. I was just trying to say that some wrong(when analysed ex-post) decisions by governments are unavoidable.

Bill,

An example of risk-averse country: Most of Australia’s banks are local banks, whereas UK has several foreign banks(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_banks_in_the_United_Kingdom).

Cheers,

Sriram

Bill,

Below is an excerpt from the paper by Trevor J. Ringrose in J. R. Statist. Soc. A (2006) titled:”Neutral umpires and leg before wicket decisions in

test cricket.”

“A two-sentence summary of the team and location effects could be as follows. Subcontinental

pitches produce a higher proportion of LBWs than elsewhere. Compared with batsmen from

other countries, subcontinental batsmen have a lower proportion of dismissals by LBW, especially

when at home, and Australian batsmen have a lower proportion out LBW when at home.

Clearly we cannot tell whether the effects of team and location are caused by umpiring or

by styles of play. However, if they are caused by umpiring then neutral umpires have behaved

similarly to home umpires, and there is no evidence that neutral umpires have remedied any bias

in LBW rates.”

Here is the link the full text:

http://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/jorssa/v169y2006i4p903-911.html

I would be interested in your take on this paper.

Cheers,

Sriram

Bill

I have a story with a couple questions for you. It regards a hypothetical situation and is an attempt for me to start putting some things together.

Lets say I discovered a new island somewhere and this island had some commodity (and this is really the only source of wealth) that turned out to be something that everyone wanted. Obviously I would put you in charge of the treasury of my new country but first I want to know if we should immediately start issuing our own currency? Does having limited resources of your own and needing a lot of things from someone else put constraints on whether you should issue your own currency? If I do issue my own new currency, how does it initially become valued on the currency markets?

I’ve been thinking about the terms poor countries and rich countries and what are all the factors which make them so. Stable government is obviously paramount but is having your own currency necessary as well? Is it more a matter of intelligently using whatever currency you have than having your own currency? You have criticized (seemingly with merit) the EU countries that have crashed and given up their sovereign currency power but are there those that might be better off using someone elses currency? If so under what conditions?

Thanks

This post by Professor Mitchell is very interesting in light of the two articles I just read about the director of Argentina’s central bank, Martin Redrado, being fired by President Fernandez. The two articles I read:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8447428.stm

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2010/01/07/business/AP-LT-Argentina-Central-Bank.html?_r=1&ref=americas

stated Mr. Redrado was being fired for “refusing to to comply with an order to use about $6.6 billion in reserves to help cover $13 billion in international debt falling due this year.” I have to say I don’t really understand the situation here. Since its last default doesn’t Argentina pay back its debt to foreign countries in its own currency? If that’s so why would having to transfer reserves from one fund to another be a problem? I’m confused.

Dear Bill, there must be a typo in the sentence

“….there is no requirement that the government in the country-of-origin is not obliged in any way to honour the private debts.”

I believe it should read “obliged”, instead of “not obliged.”

Regards,

VS

Dear VS

True. Many thanks. There are lots of typos in my blogs – haste makes ….

I appreciate your scrutiny.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

In a crucial way, the only markets that were private were entered into by people who used brokers-either traditional, in-person brokers or e-brokerages. You, I and many of your readers know that all such investors are to blame for losses that result from investments made under their approval. For those who lost in the market because their retirement insurance was based on the market, their personal responsibility is less obvious to many, but not less real.

Even though no broker was engaged, when retirement plans became Las Vegas quality, Joe and Jane retiree had the duty to scream in outrage, or at least form a club and contact their congressman en-masse. Obviously, few to none appear to have done so. Las Vegas style investing became an accepted strategy for retirement funds and what used to be staid and refined insurers.

You will recall a strange American response to the pop of the bubble, when it finally happened. Pres Bush and his trusted adviser, the older, white haired and balding econ adviser Paulson saying “trillions now or the world stops!” The Dems showed that far from the world stopping, the world kept functioning as the Dems played hardball and negotiated for a week or two to get billions for Dem spending approved before the would approve the “crucial, must happen now world saving bailout.”

Later, our Media discussion that explained this paralleled yours in this article, referring much to “banksters.” Left from blame in most explanations was political guilty parties, as well as other, non-bank financial entities. Among two that were central were two incredibly guilty parties that merited Gitmo.

These guilty twins are the financial instrument raters, S&P and Moody’s. Both called the chancy sub-prime filled financial instruments high grade. These high grade instruments were essential to the bubble growth and burst,. No investigation or prosecution of these two took place.

Misgrading those financial instruments, and the eager buying of any mortgage that Fannie and Freddie did were a huge part of the problem-neither is a bank. Most banks didn’t do one thing wrong. Overall, bankers were not gangsters. Some were, but not most.