I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Private deleveraging requires fiscal support

The Economist feature column Economics by invitation where they ask some commentators to share their thoughts on some topical issue is running with household debt this week (September 11, 2010). The topic – How far along the process of deleveraging are we? – is examining the extent to which the record levels of private indebtedness are being run down and household balance sheets reconstructed. I also noted in the discussions that have been on-going about trade and deficits on my blog that someone said that there is no evidence that budget surpluses have caused the “sky to fall in”. In this blog I explain how budget surpluses are intrinsically related to the rising indebtedness of the private sector and hence under most conditions are destabilising.

To condition the discussion, I note that the sky did fall in as a result of the unsustainable rise in private indebtedness. Further, the historical periods in which governments have run budget surpluses (for the majority of countries – that is, those without large external surpluses) have been very short compared to the periods in which governments have run budget deficits.

The other way of saying this is that the periods in which the private domestic sector has been in deficit overall (saving less than investment) have been relatively short compared to the periods that the same sector has achieved surpluses (net saving).

Every time such a government has run surpluses a recession has followed soon after and the public balance has been returned to deficit to support income growth and private saving.

So the recent decade or so has actually been unprecedented. We should always keep that in mind. Budget surpluses are rare and dangerous in most situations.

The issue of deleveraging is important because as Mike Whitney in Counterpunch reminds us:

At present, demand is weak because working people lost $8 trillion in equity when the housing bubble burst. They also lost another $2 trillion in retirement funds from the correction in equities. That means, it will take a long time before they recover and are able to spend as they did before the crisis. Fortunately, the government is not limited in the same way as everyone else. Consumers cannot print their own money, but a sovereign government (that pays its debts in its own currency) can. The government can print as much money as it likes; it is not capital constrained. And, the government should exercise that privilege when there is a compelling reason to do so, such as, when when the output gap is wide, unemployment is soaring, the economy is sputtering, and the risks of deflation are high.

The Whitney article is very solid and provides a categorical rejection of the hyper-inflation mania. It is worth reading.

The first contributor to the Economist debate was Stephen King who is the Group Chief Economist of HSBC Bank Plc. King said:

YOU decide to borrow more when your animal spirits are up. You repay debt when your-or your bank’s-animal spirits are down. Admittedly, this is a rather simplistic view but it captures the essence of the deleveraging debate. How much debt is “about right”? Because the answer depends on animal spirits which are exceedingly tricky to predict, the question falls into a category that includes, most obviously, “how long is a piece of string”?

The importance of confidence is central to the revival of private sector activity. This is typically overlooked by the deficit terrorists when they are spouting their austerity plans.

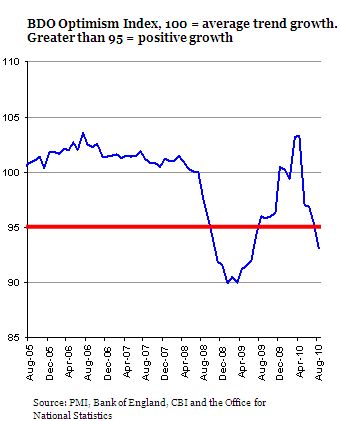

In this context, the British accounting firm BDO released their latest Business Trends report yesterday (September 13, 2010) and it provides further evidence that the deficit terrorists are derailing the growth prospects of the British economy.

The survey (which they released under the banner of “It’s alarm bells, not jingle bells, for UK businesses” reports that “(c)onfidence among UK business dips to June 2009 levels” and that:

The UK economy may be heading for a double-dip by the end of the year if the current economic trends continue … Long-term economic prospects are not showing signs of improvement, with BDO’s Optimism Index – which reflects how UK businesses expect trading to develop two quarters ahead – tumbling to 93.1 in August from 95.5 in July. These are levels not seen since the deepest parts of the recession, between November 2008 and July 2009. It is also the first time the index has dropped below the crucial 95 mark since July 2009, suggesting that the economy may contract in Q4 2010 if existing trends persist.

The following graph is taken from the BDO and illustrates their summary in the previous paragraph.

What is driving this lack of confidence? BDO say that is

The lack of confidence pervading UK businesses may coincide with government communications around forthcoming fiscal tightening, combined with the looming Comprehensive Spending Review that will set out the government’s spending plans from 2011 to 2015 … businesses seem to be convincing themselves that things are going to get really tough in 2011, and are deferring new hires and investment decisions as a result. Much of this comes from the hype around the government’s spending cuts.

So while a fiscal expansion can promote positive future expectations it is clear that austerity measures have the opposite effect. Who in their right mind would think that economic activity would rise and present a bountiful environment for private investment when the major source of current spending growth pulls out?

Stephen King argued that:

Debt is now beginning to fall but, with the housing market in a deep torpor, there is still a long way to go. Contrary to popular belief, companies also increased their borrowing as a share of GDP in recent years. They should be able to cope more easily than households, but only because the profit share in GDP has risen so rapidly. The flipside of higher profits is, of course, lower labour income. If companies can cope with higher debts, it’s only because households are struggling. All the while, government debt has been expanding rapidly. In aggregate, it’s debatable whether there’s been any deleveraging at all.

The distributional aspects are very important. In this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I outlined the changes in the distribution of national income that had occurred during the neo-liberal attack on government regulations, the welfare state and trade unions. Huge swings in real income in favour of the profit share have occurred over this period.

Labour productivity growth significantly outstripped real wages growth over the last 20 years in many economies. The gap represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.

The question then arises: if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself? This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since around 1997.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumptions goods produced were sold. But in the recent period, capital has found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that we have read about constantly over the last decade or so.

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the governments pushing for budget surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This process provided the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

The problem is that much of the government stimulus packages in the US and elsewhere have bolstered profits at the expense of labour income. With persistently high unemployment the prospects of a serious comeback in consumer spending in many nations without the simultaneous rise in household indebtedness are bleak.

King notes in this context that:

We’re now in danger of going into new, and deeply destabilising, territory. With interest rates at zero and with inflation dropping like a stone, real interest rates are now at risk of being too high. The pressure to repay debt will only intensify, threatening an Irving Fisher-style downward deflationary spiral. Inflation-or the lack of it-will be a key issue in the months ahead, for the simple reason that it will have the biggest single impact on debt dynamics in a world of zero interest rates. We used to celebrate reductions in inflation. Now we should be really worried.

This is another aspect overlooked by the deficit terrorists cum hyperinflationists. They are so stuck in the one groove that they cannot see out the window that their projections are not coming to fruition. More worryingly, the failure by governments to resolve the underlying causes of the financial crisis are really setting in place the pre-conditions for the next crisis which could come very soon.

We simply have to increase GDP growth with fiscal support to reduce unemployment and provide increased income flows to households to allow them to save. Subsidising profits is not the way this will be achieved which is why the tax breaks that the US president offered the business sector last week were so offensive.

The second contribution came from Viral Acharya, who is the Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business. He points out that the nature of the debt – driven by complex securitisation of housing mortgages – raises “complex legal issues as well as conflicts of interest issues between holders of different securitised pieces” which are preventing the unwinding of exposures.

He said that the government response has been to “fix” “the balance-sheets of the financial sector, in terms of backstopping debt and making capital infusions” but that “this was not tied to writedowns of the debt of underlying assets they held, namely mortgages”.

The attempts to boost housing prices in his view as a means “to effect household de-leveraging” have “not been that effective”.

One of the key reasons that the US government’s approach has failed in this regard is because they have allowed unemployment to persist at such damaging levels. In many cases, a good debt becomes a bad debt as soon as the person holding the debt loses their jobs.

While I am not denying the extent of the sub-prime exposure, the financial calamity would not have been anything like it has been if the government had have staunched the job loss early. It could have used targetted fiscal measures to do that but was too caught up in neo-liberal paradigms to directly create public sector employment.

Acharya wants the government to create a “special public utility” to take over the bad debts in the financial sector. In general, I do not favour such an approach – the socialisation of private loss. I would nationalise the banking sector and scale it down significantly and leave the private shareholders to take the losses (which after all is the logic of capitalism and the rules under which they enjoy their profits!).

Please read the following blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks for further discussion on that topic.

The other point that Acharya makes which is interesting is that:

In Europe, my reading is that we may not have fully deleveraged the financial sector either. There is reluctance to get banks to issue enough capital to deal with sovereign debt losses on government bond holdings. Such reluctance is a signal that governments are going the path of backstopping rather than reshaping balance sheets … In Europe, governments need to come out of denial and address both government and financial sector balance sheets with some alacrity. Simply postponing these issues-in the US and in the Europe-will only entrench the slow growth path further.

The sovereign debt problems and the vulnerability of the banking system in the Eurozone are all due to the flawed monetary system that they designed to impose fiscal control over member governments. None of the EMU governments are sovereign in their own currency and cannot defend their banking system in the even of a collapse.

We easily see this vulnerability when we appreciate that it has taken the ECB to act outside the strict rules set down by the Lisbon Agreement (which set the EMU up in conjunction with earlier understandings reached in the Maastricht Treaty) to temporarily stem the tide which will eventually see the Greek government for one have to restructure its sovereign debt liabilities (or exit the zone).

Please read my blogs – Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown – A Greek tragedy … – España se está muriendo – Exiting the Euro? – Doomed from the start – Europe – bailout or exit? – EMU posturing provides no durable solution – for more discussion on this point.

The final contribution came from Richard Koo, who is the Chief economist, Nomura Research Institute in Japan. I have discussed his ideas previously in this blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy. Koo’s insights, though not 100 per cent MMT-consistent, are worth considering.

He said:

… when the whole economy is deleveraging, the economy is likely to become far weaker and its asset prices far lower than when the individual economic agent has embarked on its path to deleveraging. In other words, even if individually agents thought they could finish deleveraging in three years, with everybody deleveraging at the same time, it could easily end up taking far longer than three years. When the Japanese private sector embarked on deleveraging around 1992-3, nobody at that time thought that the process will eventually take 15 years.

Moreover, governments can play havoc with the economy by pushing for premature fiscal consolidation when their private sectors are still deleveraging. This was amply demonstrated in the US in 1937 and Japan in 1997, with both events prolonging the recession and the task of repairing balance sheets by very many years. If it were not for these policy mistakes, the US unemployment rate would have fallen to single digit by the end of 1930s, and Japan’s recession would have ended by the end of 1990s.

This is 100 per cent consistent with MMT insights.

First, it recognises the fallacy of composition that arises when one tries to make conclusions about macroeconomic behaviour on the basis of what a single person might be able to achieve. So if everybody is withdrawing spending in an effort to reconstruct their precarious balance sheets the macroeconomic impacts are large and make it harder overall because total income losses are larger.

Remember always – saving is a function of income. An economy expands saving by expanding national growth and employment. It is much easier to delever overall in a growth environment than in a recession.

This is one of the reasons why multi-lateral fiscal austerity would be so destructive. The macroeconomic effects are overpowering of anything an individual can conjure for themselves.

Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

Which leads to the second point that Koo makes which is seemingly overlooked or not understood by the deficit terrorists. Delevering has to be supported by government spending. As the private sector withdraws spending (aggregate demand) and starts reducing its debt levels, the only way that GDP can continue growing is if there is an external trade boom (unlikely overall) and/or fiscal support.

As Koo notes, different economies have been there before several times and they have always learnt the hard way.

Fiscal deficits have to provide the support to demand to keep national income growing to provide the capacity for the private sector to save. It is a basic macroeconomic reality. The paradox of thrift has to be subverted.

The paradox of thrift tells us that individual virtue can be public vice. So what applies at a micro level (ability to increase saving if one is disciplined enough) does not apply at the macro level (if everyone saves aggregate demand and, hence, output and income falls without government intervention).

An individual who tried to increase his/her individual saving (and saving ratio) would probably succeed if they were disciplined enough. But if all individuals try to do this en masse, and nothing else replaces the spending loss, then everyone suffers because national income falls (as production levels react to the lower spending) and unemployment rises. The impact of lost consumption on aggregate demand (spending) would be such that the economy would plunge into a recession.

As a result, incomes would fall and individuals would be thwarted in their attempts to increase their savings in total (because saving is a function of income). So what works for one will not work for all. This fact is overlooked by the mainstream macroeconomic analysis.

The causality reflects the basic understanding that output and income are functions of aggregate spending (demand) and adjustments in the latter will drive changes in the former. It is even possible that total savings will decline in absolute terms when individuals all try to save more because the income adjustments are so harsh.

Keynes and others considered fallacies of composition such as the paradox of thrift to provide a prima facie case for considering the study of macroeconomics as a separate discipline. As noted, up until then, the neo-classical (the modern mainstream) had ignored the particular characteristics of the macro economy that require it to be studies separately.

They assumed you could just add up the microeconomic relations (individual consumers add to market segment add to industry add to economy). So the representative firm or consumer or industry exhibited the same behaviour and faced the same constraints as the individual sub-units. But Keynes and others showed that the mainstream had no aggregate theory because they could not resolve the fallacy of composition.

So they just assumed that what held for an individual would hold for all individuals. This led the mainstream opponents to expose the most important error of the mainstream reasoning – their attempts to move from specific to general failed as a result of the different constraints that the macroeconomic level of analysis invoked.

The paradox of thrift allows us to understand a crucial role of the budget deficits which is to finance the private desire to save.

Accordingly, the national economy can produce a certain volume of goods and services in any period if it is fully employing all available resources (that is, unemployment = less than 2 per cent and no underemployment). This production generates income which can be spent or saved.

If the private sector desires to save, for example, $10 in every $100 it receives then that $10 is lost from the expenditure stream. If nothing else happens, unsold inventories will appear and firms will start to lay off workers because the production level is too high relative to demand. Firms project demand expectations and make their production decisions based on what they think they can sell in the forthcoming periods.

The decline in economic growth then reduces national income which in turn reduces saving, given that the latter is a positive function of total national income.

But if the economy is to remain at full employment all the output produced has to be sold. Enter the national government. It is the one sector that can step in and net spend the $10 in every $100 to fill the “spending gap” left by the saving. All the output is sold and firms are happy to retain the employment levels that created the output. The system is in what economists call a “full employment equilibrium”.

Yet, notice what has happened. The net spending by the government (the deficit) ratifies the savings decisions of the private sector. The budget deficit maintains full employment aggregate demand and the resulting national income produced generates the desired private saving level. So the budget deficit finances the private saving on a daily basis.

So there is no particular problem for the economy in households increasing their desired saving. The solution does not rely on private investment improving any time soon, although a rise in capital formation would quicken the pace of recovery and underpin higher future rates of growth.

The leakage from the expenditure stream that occurs as household increase their saving can be filled by a rising public spending “injection”. As long as the government sector “finances” that rising saving behaviour from the households economic growth can continue and the paradox of thrift effect thwarted. The rising net spending promotes income and employment growth, which combine to generate the rising saving capacity desired by the households. It is a win-win.

By recognising the importance of the fallacy of composition in mainstream economics at the time was a devastating blow to its credibility. How short our memories are? How the mainstream ideas that were discredited so comprehensively in that period have been able to reassert themselves as the dominant discourse is another story (of puzzling dimensions).

Koo captures this understanding well:

The double dip brought about by premature fiscal consolidation lengthens the recession because people become so pessimistic after the dip that they effectively lower the level of what constitute a comfortable level of debt. Their renewed efforts to de-lever, in turn, weaken the economy even further. With governments of the UK, Spain, Ireland and the Republicans in the US pushing for fiscal consolidation when private sectors of these economies are still fully in deleveraging mode, the danger of repeating the US and Japanese mistakes of 1937 and 97 are all too real today.

The problem with budget surpluses

I have often made the statement that the government balance is the mirror, dollar-for-dollar, of the non-government balance. It should be written on our walls and recited often. It provides a very simple framework for thinking through more complex problems. The problem is that people really do not understand that simple accounting statement and so can never really get to the bottom of a lot of other more involved reasoning.

It bears on the above discussion. The failure to recognise this relationship is the major oversight of neo-liberal analysis. In aggregate, there can be no net savings of financial assets of the non-government sector without cumulative government deficit spending. The sovereign government via net spending (deficits) is the only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings) and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save and hence eliminate unemployment. Additionally, and contrary to neo-liberal rhetoric, the systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses is necessarily manifested as systematic declines in private sector savings.

Further, the decreasing levels of net private savings which are manifest in the public surpluses increasingly leverage the private sector. The deteriorating debt to income ratios which result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity.

So a growth strategy predicated on fiscal surpluses and increasing levels of private debt is always inherently unstable and ultimately unsustainable.

First, the levels of debt rendered private agents increasingly susceptible to small changes in external conditions including policy changes. For example, the increasing fuel prices in recent years endangered the solvency of highly geared households. In turn, debt defaults would be less confined than in the past because of the size of financial derivatives market which has grown to drive the proliferation of credit. Second, private agents eventually had to increase their saving to reduce the precariousness of their balance sheets.

Both sources of instability mean that aggregate demand would fail resulting in unsold inventories, reductions in production levels, job loss and rising unemployment.

The resulting unemployment is involuntary in nature by which we mean labour unable to find a buyer at the current money wage. It also invokes the idea of a systemic macroeconomic constraint that renders an individual powerless to improve their employment circumstances.

Orthodox macroeconomic theory struggles with the idea of involuntary unemployment and typically tries to fudge the explanation by appealing to market rigidities (typically nominal wage inflexibility). However, in general, the orthodox framework cannot convincingly explain systemic constraints that comprehensively negate individual volition.

The modern monetary framework clearly explicates how involuntary unemployment arises. The private sector, in aggregate, may desire to spend less of the monetary unit of account than it earns. In this case, if this gap in spending is not met by government, then unemployment will occur. Nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless they somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save and increase spending.

The non-government sector depends on government to provide funds for both its desired net savings and its tax obligations. The private sector cannot by itself “net save” because saving is a signal to lend and so savers are always in an accounting sense matched by a borrower.

To obtain these funds, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed currency units. This includes, of-course, offers of labour by the unemployed. Thus, unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

The concept of a budget surplus is often misunderstood. In the recent Australian federal election campaign there was talk of a big black hole in the fiscal bucket.

MMT allows you to see that there is no hole because there is no bucket. To explain this we need to understand what happens when the sovereign government runs a budget surplus.

It is often argued that the surplus represents “public saving”, which can be used to fund future public expenditure. With the current decline in government revenue and the need for a dramatic fiscal injection generating rapidly increasing deficits, many commentators are erroneously claiming that the governments will run out of funds.

In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we should note that government spends by crediting a reserve account. That balance doesn’t “come from anywhere”, as, for example, gold coins would have had to come from somewhere. It is accounted for but that is a different issue. Likewise, payments to government reduce reserve balances.

Those payments do not “go anywhere” but are merely accounted for. In the USA situation, we find that when tax payments are made to the government in actual cash, the Federal Reserve generally burns the “money”. If it really needed the money per se surely it would not destroy it. A budget surplus exists only because private income or wealth is reduced.’

The following accounting relation, often erroneously called the government budget constraint (GBC) can be used to show the impact of budget surpluses on spending and private wealth:

where G is government spending net of interest payments on debt, i is the nominal bond rate, B is the stock of outstanding bonds, M is base money balances, and T is tax revenue. In an accounting sense, when there is a budget surplus then (destruction of base money) and/or (destruction of private wealth).

The budget surplus may be applied to running down debt (that is, forcing the private sector to liquidate its wealth to get cash) but this strategy is finite.

For example, in the period up to around 2007, the then conservative Australian government followed the pattern of several sovereign governments and established a sovereign fund (which they called the Futures Fund). This amounts to the Treasury competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital.

Please read my blog – The Futures Fund scandal – for more discussion on this point.

However, this behaviour has been grossly misrepresented as providing future savings. Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even.

In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments.

The alternative when a surplus is generated is to destroy liquidity (debiting reserve accounts) which is deflationary. The weaker demand conditions would force producers to reduce output and layoff workers with rapid increases in joblessness. Investment irreversibility driven by uncertainty of future demand conditions then retard capacity growth and prolong the downturn.

These dynamics are covered in my In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

However, we should never forget that the pursuit of public surpluses has necessitated an increase in the net flow of credit to the private sector and increasing private debt to income ratios.

The current financial crisis is now evident that a threshold has been reached where the private sector, by circumstance or choice, becomes unwilling to maintain these deficits? It also means that reliance on rising indebtednesses to underwrite private spending is now unsustainable and an alternative growth strategy, based on fiscal expansion has to be introduced.

In terms of fiscal policy, there are only real resource restrictions on its capacity to increase spending and hence output and employment. If there are slack resources available to purchase then a fiscal stimulus has the capacity to ensure they are fully employed. While the size of the impact of the financial crisis may be significant, a fiscal injection can be appropriately scaled to meet the challenge. That is, there is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending.

When fiscal stimulus is inappropriate …

I was thinking that my next book on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is going to be a spy thriller and will be designed to expose various secrets that the Pentagon might find worrisome. That will ensure a sell-out.

My strategy was informed by the news that Pentagon tries to buy entire print run of US spy expose Operation Dark Heart.

Seriously, are these characters for real.

The UK Guardian reported (September 13, 2010) that:

US defence department attempts to prevent book by former intelligence officer Anthony Shaffer from reaching the shops. It’s every author’s dream – to write a book that’s so sensationally popular it’s impossible to find a copy in the shops, even as it keeps climbing up the bestseller lists.

And so it is for Anthony Shaffer, thanks to the Pentagon’s desire to buy up all 10,000 copies of the first printing of his new book, Operation Dark Heart. And then pulp them.

The only point I would make is that while I am happy Anthony Shaffer is employed I do think the US government could spend the public money more productively. Like hiring a gang of unemployed workers to bulldoze the whole Pentagon building to the ground and turn it into a nature park for the citizens to enjoy.

And further, we all know what a stuff up the US attempts in the Middle East and in Afghanistan and Pakistan are anyway.

But then I thought a little further about my own publishing strategy. I actually want the next book to be at least as widely read as my last – so perhaps I better not mention spies and the US government at all. That way it will escape the pulping machine.

Conclusion

The point to understand is that private sector deleveraging cannot occur in times of fiscal contraction unless there is a net exports boom. Not all countries can enjoy a net exports boom and probably none can when everyone is engaging in fiscal austerity.

On-going public deficits are essential to allow this necessary process to take place. For those (including notable progressives) who claim that all that is happening now is that public debt is replacing private debt and that the problem is that overall debt levels need to be reduced I recommend learning the basic national accounting relationships I outlined above.

Further you might like to read this blog – Debt is not debt – for further education.

That is enough for today!

I do not understand the sentence:

In the paragraph above you write, about the desire of the private sector to spend less of the monetary unit of account than it earns. And that nominal wage cuts will not clear the labour market, unless they somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save and increase spending. Isn’t this desire to spend less than it earns net saving?

“But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even.”

Bad recurring riff. This is an entrenched government accounting misclassification, and that’s all it is. It shouldn’t exist, and it shouldn’t be used in the wrong way to support the right (MMT) logic. There’s no deficit at the margin when properly classified. This should be included only in a correctly constructed flow of funds statement – not embedded as part of a budget deficit/surplus statement. Poor government accounting methodology.

Bill, you say surpluses have always caused bad effects. Surely that is because the taxation was misdirected at consumption/wages rather than at asset prices etc. Just as you always point out that stimulus aimed at increasing asset prices (such as QE or bank bailouts) wont save the economy so it seems to me that taxation is bad for the economy if aimed at consumption but fine if aimed at assets. My impression is that if house/farmland/stock prices were much lower than currently but fiscal efforts increased employment, then things would start functioning again

Thanks for this post Bill. You often use repetition to get your point across. I occasionally post here favoring tax cuts for working people as a solution to the current economic situation. The reason I feel this way is because you state:

“The problem is that much of the government stimulus packages in the US and elsewhere have bolstered profits at the expense of labour income. With persistently high unemployment the prospects of a serious comeback in consumer spending in many nations without the simultaneous rise in household indebtedness are bleak.”

I totally favor a a JG and our infrustructure is in serious need of repair. But all that spending will do very little to solve the “origin of the crisis”. Sorry for my repetitive message, but the above quote makes my point. Do you (MMT) have different solution for the wage share problem?

Bill,

Previously when you have mentioned working on an MMT textbook I’ve had the impression it’s a real, active project. Is that accurate, and if so, any estimates on when it might be published? (Within the next 1-2 years, or further out?)

Also, I thought this post was particularly good in that included many important core concepts.

However, I still disagree with your negatively-framed assessment that automatic-stabilizer-driven late-1990s US surpluses “squeezed liquidity” and contributed meaningfully to the rise in private sector debt. That they squeezed liquidity at that time was a feature not a bug! True the US was not at full employment as you define it, but that was a distributional issue not a macro sectoral balance issue, and could have been solved by a shift in tax policy within the context of an unchanged government surplus. (Or a job guarantee plus a higher top marginal tax rate or capital gains rate). IMO only if inflation had been dangerously low (which it wasn’t) should the government surplus have been actively reduced via policy changes. By “squeezing liquidity” the government likely limited the size of the dot com boom and bust cycle.

And yes I agree with your description of the unsustainable distributional problems of recent decades (increased share of profits to capital vs labor) and that they have played a role among other factors in growing private debt. But from a policy perspective distributional problems can (should?) be considered independently from the aggregate sectoral balances.

One key difference of MMT from mainstream Keynesian economics seems to be that the mainstream is willing to force those with higher incomes to reduce their savings rates (via tax policy and higher top marginal rates for those who truly just save their excess income beyond a fixed nominal spending desire) when the non-government sector as a whole tries to increase its savings, while MMT seems to say “let everyone save more if they want, even those with high incomes”, just run a larger deficit to accommodate that desire. So while both approaches favor sustaining aggregate demand in the present, MMT seems predisposed to allowing future distributional issues (wealth and its consequent spending disparities) to grow larger than they otherwise would. I’m not casting judgment here, as there are merits and drawbacks to both approaches, and I know I have oversimplified by ignoring behavioral and demographic dynamics and other factors. But I think MMT authors underplay this connection between wealth disparity and size of government deficit.

Of course none of this is to diminish the point that active government austerity measures at a time of high unemployment and low and falling inflation are very damaging, which is your more important point.

They don’t ‘generally’ destroy it or shred it, instead they destroy it only if the notes are unfit and mutilated. They keep them, The Fed takes the notes from the Treasury and reduces the item “currency in circulation” and credits the Treasury General Account.

The punch is lost if one describes it this way but thats the ontology.

Okay, I realize now I went astray on the last comment… If it is the upper income households driving the attempted increased savings, no realistic tax policy is going to target and eliminate just that increase in savings, so sustaining current aggregate demand really must involve an expanded government deficit. Plus it’s probably impossible to set up a single tax framework to do what I described without relying on proactive policy in response to every ebb and flow of the economy, which would be foolish. So disregard most of that point, sorry!

But there are several ways in general I feel that MMT underplays the dynamic feedback effects between government policy and private sector actions. For example on the topic of drivers of private borrowing… one of them is simply a system (in the US) that has maximized consumption, so many people will spend income plus whatever they can borrow (for the largest house, SUV, buying stocks, etc). So government supplementing those incomes might not have lessened private borrowing on anything close to a one-to-one basis, and may have even allowed it to increase. Of course I know MMT authors have to make simplifying assumptions in presenting material so I don’t think this contradicts anything at the core of MMT, but there are times I’ve felt not tying in some of these dynamics left an analysis somewhat lacking. Could just be my misunderstanding though!

hbl,

That is the same point that RSJ was making. If there is no redistribution of income, the government deficit will have to be bigger every time, because the top percentile won’t spend their savings. If the top percentile won’t spend their excess savings, the government should tax them away and spend their excess savings into the economy. It is in their collective interest to spend more because it is going to come back to them in the form of profits anyway. And it comes back to these government schemes that encourage saving because people are led to believe that savings are needed for investment.

Dear JKH (at 2010/09/14 at 22:16)

I wasn’t talking in a strict accounting sense. I know how the government accounts for these transactions. But in economic concept the transactions are as I indicate.

best wishes

bill

Dear Stone (at 2010/09/14 at 22:18)

You said:

No, I don’t say that. In some situations, budget surpluses are the sensible and responsible policy outcome. For example, a nation with strong net exports can still provide high economic growth and strong employment growth, with first-class public infrastructure all the time while the private domestic sector is net saving with the budget in surplus. In this case, the budget surplus is necessary to avoid excessive nominal aggregate demand growth.

best wishes

bill

Ramanan 4:10

correct

Dear hbl (at 2010/09/15 at 4:01)

The textbook project with Randy Wray is still active and I work on it regularly. We are hoping it will be in a working form by early to mid 2011.

You said:

One should be careful in distinguishing what is necessary to maintain growth when the non-government sector desires to save and what is desirable policy. MMT tells you what is necessary but you have overlay a value system to come up with the desirable policy within the constraint of what is necessary.

Some of the main proponents of MMT may not be so concerned with distributional equity. I am clearly concerned about it and prefer a more egalitarian access to the distributional system based on need rather than contribution. So how I might manage the demand gap and view differential saving outcomes by income class would be different to how some other MMT person (hypothetically) would do it.

For example, I prefer public spending rather than taxation changes because I still have a view that government can add value to society whereas those who prefer tax cuts (say to stimulate demand) have a view that the private market is the preferred allocative vehicle.

best wishes

bill

I am suspicious of that large net export surplus and government surplus is OK for the domestic economy. Sweden have had since about 1993 constantly very high export surplus of about 7%, government have “saved”, turned a net public debt (90s crisis) to a significant net surplus. The government surpluses have not at all been of the magnitude of the net export surplus,( I haven’t checked the Current Account only the net export in the GDP). At the same time we have had very high unemployment the last 18 years. The Swedish households are in top league in debt, compared to percent of GDP or compared to disposable income. From 2000 to now a bit less than 40% of mortgages have been for actual home/house purchases, the rest is borrowed for consumption (or whatever) from the “everlasting” rise in value in the home/house piggy bank. The right wing gov. did a strategic cut of real-estate tax so the raising prices keep going and they will as it looks win a second term on Sundays election. The largest component of rising consumption last quarter was new cars.

These private savings generated from large export surpluses does seem to spread over the folk-community in an asymmetrical way.

For fun I got the idea to see how much the accumulated export surplus was. I did add the constant prices table on GDP guess that would equate a modest value rise on the assets. It turned out to be almost exactly the same amount that the Norwegian people did have in their oil fund, about 3000 billion Swedish crowns. Seems that someone got an windfall while the Swedes had high unemployment and consuming withdrawing from the home/house piggy bank.

The German economist Jürg Bilbow did have couple of articles on the German desire for export surpluses:

Suffocating Europe

“The real irony in this German tragedy is that German beggar-thy-neighbor policies have effectively forced a fiscal union upon Europe. Or, rather, if not a fiscal union, a general default it will be. The point is that Germany’s notorious trade surpluses vis-à-vis its European partners must by necessity have a financial counterpart. In one way or another, German banks financed the country’s export successes by lending to today’s crisis countries. They did so as willing borrowers were hard to come by at home when the country – duped by its own political leadership and powerful export lobby – prescribed itself a decade of belt-tightening, flat real wages, and flat consumption growth, that is. Public celebration of repeated wins of the world export championship title made the duped Germans even feel good about it.

Once credit markets stop lending, trade surpluses cannot continue either. A creditor country government may then realize that it might want to step in instead. For if it does not, its intra-area trade surpluses will have to evaporate over night, while its banks will face corresponding writedowns on debtor country debts. …”

So a growth strategy predicated on fiscal surpluses and increasing levels of private debt is always inherently unstable and ultimately unsustainable.

Enter moral hazard, the Greenspan/Bernanke “put,” the rescue packages (bailout), “forbearance,” non-accountability, etc. Absent these, financiers and corporatists wouldn’t be so bold, relying on government to pull them out when debt goes bad. This is the antithesis of capitalism. Basically, it is blackmail and holding the country hostage. It really is a form of terrorism, given the economic consequences.

Marhall Auerback has a good illustration of my 14:06 at Naked Capitalism.

TARP Was Not a Success – It Simply Institutionalized Fraud

Another good read today. I’m enjoying my economics education 35 years late.

A comment in this article sparked a thought process. Basically, Monetary expansion by investment in productive assets is good and expansion by investment in non productive assets is bad. I’m trying to figure who would do the least worse job. Banks or Government. (Maybe there is a good balance of both)

Can anyone direct me to some information: Comparing. 1. Monetary expansion through Government deficit spending vs 2. Debt creation through private banks and the fractional reserve system?

Off topic but I’m also still pondering if a way can be found to transition into a credit based currency (proper greenbacks) and full reserve banking. I hear the path is difficult and fraught with danger, but surely it is a better system for long term societal stability? Any info?

Hope Ray doesn’t ambush me today.

Andrew Wilkins, as far as I can work out MMT amounts to a project (perhaps unintentionally) to enlarge both banks and governments of first world countries at the expense of workers in third world countries. It seems on the face of it to be Reganomics/neocolonialism but with a job creation scheme fig leaf. What on earth is this “desire to net save” all about? If you give people more money than they can work out how to spend they will net save. That “desire” will expand to whatever amount of money you print and dish out to them. Saying that money will be printed so long as it is satisfying Goldmans Sach’s “desire to net save” comes across as fairly open ended to me.

Stone,

Ouch, that sounds like an evil scheme to create asset bubbles, followed by hyperinflation. All caused by the global elite in pursuit of a single World currency. S.P.E.C.T.R.E. is at work.

Oh no!….. We’ve already had the bubbles…

I thought Bill was something like a socialist libertarian. Does he have a third nipple?

Stone,

Maybe I don’t grasp your argument. I didn’t think MMT was part of a big government plot by the elites to deprive the 3rd world. I thought that is just normal human behaviour through history.

stone,

First world countries will always look after themselves. Third world countries need to use their own fiat currency to create a stable legal framework and allow division of labour that helps everybody within their own domestic economy.

Which is what the Eastern countries are doing – in fits and starts.

You have to work with human behaviour as it is, not as you would like it to be.

Andrew,

My understanding is that fractional reserve is a myth. Banks create a lump of money today in return for a charge over a future income stream. Those charges are the bank’s assets and the excess of the charge over the lump sum is the profit stream. That’s how money lending has always worked.

Banks don’t invest. They lend money in return for charges over future income. If an investment is non-productive then it is surely for regulation and taxation to ensure that the income stream doesn’t exist. Then banks won’t lend money against such an investment.

Neil Wilson, slave trades happened because human nature leads people with stronger governments to exploit those with weaker governments (such as the trade from West Africa to the Americas or the trade of slaves from medieval England and Ireland to North Africa etc etc). That is just human nature and it could be argued that it is the stupid fault of those who have weak governments. I’m inclined to also cast ill judgement on the slave traders and slave owners. To my mind if every country tries to “punch above its weight” rather than “pull its weight”, then we all just get punched in the face. I think citizens of first world countries have a much greater sense of decency than you give them credit for, they just don’t realize what is going on in their name.

On your other point, the sad fact is banks lend money so as to feed off asset price inflation- governments try and ramp up that process as much as they can so that their prospective countries can “punch above their weight”.

stone: as far as I can work out MMT amounts to a project (perhaps unintentionally) to enlarge both banks and governments of first world countries at the expense of workers in third world countries.

Please peruse the archives here, as well as at New Economic Perspectives. BTW, Bill has a record of serving as a consultant to Third World countries.

Thanks for the helpful comments. These are difficult and ephemeral concepts to grasp.

I think I get it, then … phoof…. it’s gone again.