I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

Export-led growth strategies will fail

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) released their annual Trade and Development Report, 2010 yesterday (September 14, 2010). The 204 page report which I have been wading through today is full of interesting analysis and will take several blogs over the coming weeks to fully cover. The message is very clear. Export-led growth strategies are deeply flawed and austerity programs will worsen growth and increase poverty. UNCTAD consider a fundamental rethink has to occur where policy is reoriented towards domestic demand and employment creation. They consider an expansion of fiscal policy to be essential in the current economic climate as the threat of a wide-spread double dip recession increases. The Report is essential reading.

I often say that unemployment is the largest waste of people that the capitalist system can conjure. I was wrong. Today, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation and the World Food Program pre-released some findings – from their upcoming (October) publication – The State of Food Insecurity in the World (SOFI).

The pre-release coincided with the upcoming New York Summit hosted which aims to “speed progress towards achievement of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the first of which is to end poverty and hunger.

The FAO say that there is:

… a child dying every six seconds because of undernourishment related problems …

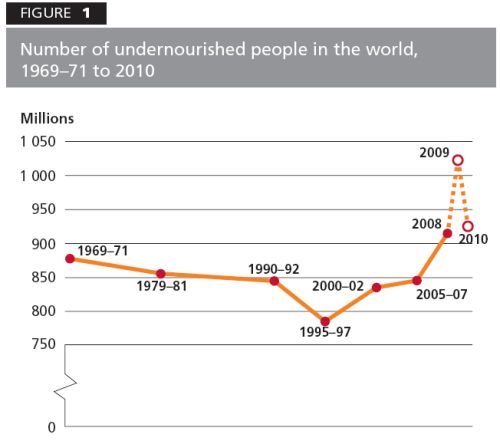

The following graph is taken from the briefing document that the FAO/WFP provided and shows that over the period that the neo-liberal agenda was prominently being pushed by the IMF and other organisations the number of people who are not getting enough food has increased dramatically.

The FAO/WFP discussion conditioned the way I felt about economics today – and dare I say it – life in general.

During the crisis the IMF insisted on pro-cyclical fiscal policy stances in a majority of countries operating under “IMF arrangements”. That is, they forced the nations to run policies that made the recession worse.

Please read my blog – IMF agreements pro-cyclical in low income countries – for more discussion on this point.

The austerians are now forcing the same pro-cyclical policy strategy on the advanced nations which will entrench poverty in those countries via unemployment.

Unemployment is the largest source of poverty and starvation so that should always be our policy priority – virtually without regard in my view.

Anyway, the fiscal austerity camp got another warning today from UNCTAD.

The UNCTAD Report concludes that the pursuit of fiscal austerity is not a sound policy path to follow at present:

The global upturn from what is considered the worst economic and financial crisis since the 1930s remains fragile, and a premature exit from demand-stimulating macroeconomic policies aimed at fiscal consolidation could stall the recovery. A continuation of the expansionary fiscal stance is necessary to prevent a deflationary spiral and a further worsening of the employment situation.

Does anyone need it to be clearer than that?

So in the last week we have had UNCTAD, the ILO, and the right-wing bully twins – the IMF and the OECD – all converging on the same viewpoint, albeit with different emphasises and qualifications. The common theme is that the risk of a double-dip recession is great and that continuing fiscal support is required to fill the spending gap.

Please read my blog – Chill out time: better get used to budget deficits – for more discussion on the need for on-going budget deficits in most countries.

UNCTAD’s policy conclusion made me think of an article in the latest Bank of International Settlements Quarterly Review September 2010 – Debt reduction after crises which examined among other questions “the implications of declining debt for output growth?”

The authors contend that the process of private debt-reduction may not damage growth because:

… changes in the flow of credit (ie the second derivative of credit) are more relevant for output growth than changes in the stock (ie the first derivative)

The BIS article was the basis of an article in the Financial Times yesterday (September 14, 2010) by A Japanese lecture for bond investors – which asserted that “falling debt levels necessarily slow economic growth”. I wonder why the author thought there was a need to actually think anyone actually thought the opposite.

The English translation of the BIS conclusion about first and second derivatives (above) is that is is spending that ultimately matters for economic growth and employment. Spending is a flow not a stock. But we also know that to reduce a stock there has to be a net outflow.

They point out that when credit is contracting the stock of debt can still be rising which is just a reflection that the flow is getting smaller but still positive.

But the way the private domestic sector overall reduces the stock of outstanding debt is to spend less than they earn or can access via credit (or other means such as asset sales, or running down savings).

So the point is moot. A wholesale deleveraging of the private sector will leave a spending gap whether it is driven by a reduction in the flow of credit or other means.

However, I may return to this argument towards the end of the week because there are all sorts of interesting complexities.

The UNCTAD point is one I have consistently been making. There is no magic formula that maintains growth. There are three sectors that can influence it: the private domestic sector (via consumption and investment); the government sector (via net spending) and the external sector (via net exports). The first and the last sectors named comprise what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) refers to as the non-government sector.

When net exports are draining demand (that is, the current account is in deficit) and private domestic spending is flat (and credit growth slow), then the economy has to be nourished by sufficient net public spending (that is, budget deficits) to support utilisation of the productive capacity.

There are no free kicks.

Please read my blog – How do budget deficits finance saving? – for more discussion on this point.

Austerity proponents have somehow conjured up the argument that if the main spending crutch at present (public demand) is cut then two things are likely to happen. In part, the argument depends also on the cuts being, in part, driven by attacks on wages and employment conditions in the name of increased competitiveness.

They don’t think that it is better to increase a nations competitiveness by taking the high wage-high productivity route. Rather they are into the race to the bottom strategy – drive down employee morale and wages so that unit costs fall that way. It is the low productivity path and will never support significant increases in the real standards of living for the citizens.

The austerians make two points then. First, that the lower budget deficits will signal lower future tax rates for the taxpayers in the private domestic sector who will then immediately increase consumption and investment because they don’t have to save for the future to pay for the higher tax burdens had the deficits remained at their pre-austerity levels.

This is the Ricardian Equivalence argument. I provide a critique of it in this blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow. It is essentially a crackpot theory which has never received any empirical support anywhere.

Moreover, reductions in deficits historically arise from growth rather than tax hikes. The assumption that the government has to pay the deficit back is nonsensical in the extreme. Deficits are flows not stocks. You cannot pay them back. What you can do is reduce the outflows (government spending) and/or increase the inflows (tax receipts).

Courtesy of the automatic stabilisers, this happens in no insignificant way as the economy grows again. Tax revenue increases but not because tax rates are increased. The growing tax revenue arises because more people are employed and paying taxes and business profits are higher.

Second, even if domestic spending does not pick up, the austerians claims that the process of wage and price deflation brought on by the attacks on unions and public sector entitlements etc will increase the real competitiveness of the economy. This will allegedly spawn an export-led return to economic growth even as the government is bailing out.

I deal with the absurdity of that argument in this blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition.

You might also like to read this blog – Pushing the fantasy barrow – for further analysis.

The UNCTAD Report also categorically rejects the export-led growth model for developing countries (and the logic extends to advanced nations). They say:

It is becoming clear that not all countries can rely on exports to boost growth and employment; more than ever they need to give greater attention to strengthening domestic demand … The shift in focus on domestic-demand-led growth is necessary both in developed and emerging-market economies with large current-account surpluses and underutilized production potential in order to prevent the recurrence of imbalances similar to those that contributed to the outbreak of the global financial crisis. But it is also important for many developing countries that have become heavily dependent on external demand for growth and for creating employment for their growing labour force.

Unemployment is the most pressing social and economic problem of our time, not least because, especially in developing countries, it is closely related to poverty.

Does anyone need it to be clearer than that?

When nothing is happening externally the only show left in town is the domestic economy. Fortunately, appropriately designed fiscal interventions can target domestic growth and, if desired, take pressure of the import sector at the same time.

That is, increasing budget deficits can be composed of policy mixes that increase aggregate demand but focus it on stimulating domestic (non-tradable) activity and reduce the normal growth in imports that would be associated with rising domestic incomes.

More generally, export-led growth strategies without a corresponding quality diversification in the mix of exports and due regard for the consumption needs of the domestic economy tends to generate inflation pressures for several reasons, including the necessity of importing raw materials and intermediate goods that have been rising in price.

Further, production of goods for export reduces the portion of output available for domestic consumption – generating incomes that raise demand but without satisfying this demand through increased supply available for consumption.

MMT does not object to an exclusive export focus purely on excess demand grounds, but rather because it would unduly direct domestic production to external consumers, rather than using domestic resources to produce for domestic consumption.

Further, competition in export markets often leads to domestic policy to keep wages and other costs low – both to fight the domestic inflation pressures (fuelled in part by the processes just outlined) but, more importantly, to compete with other low wage developing nations.

The typical outcome of these dynamics is that the domestic population does not share in the economic growth that is generated by exports of it occurs. Poverty and social unrest often worsens even as the economy grows.

Further, by keeping wages low, such policy prevents development of strong domestic markets to absorb output, forcing the nation to continue to export its output. This means the nation’s fate continues to be largely in the hands of external markets, and in competition with newly developing nations.

UNCTAD are more than explicit about the desired emphasis of the fiscal policy:

… it is important that the macroeconomic policy framework be strengthened to promote sustainable growth and employment creation in both developed and developing countries. Past experience and theoretical considerations suggest that a sustainable growth strategy requires a greater reliance on domestic demand than has been the case in many countries over the past 30 years. In such a strategy, job creation for absorbing surplus labour would result from a virtuous circle of high investment in fixed capital leading to faster productivity growth with corresponding wage increases that enable a steady expansion of domestic demand. Especially for developing countries, this may call for a rethinking of the paradigm of export-led development based on keeping labour costs low.

So countries that think they can undermine the wages and conditions of their most valuable asset – their workforces – and ship low cost-low productivity items to other countries and, in doing so, deprive their own citizens of the use of those resources and products – and still prosper – should think again.

They are unlikely to prosper and resolve their chronic unemployment problems.

MMT tells us that a sovereign government can always provide enough work to absorb the domestic labour supply that is not engaged by the non-government sector. It can do this using a combination of career-oriented public sector employment supplemented with a Job Guarantee, where anyone can get a decent minimum wage job on demand within the public sector.

That should be the policy priority now. It is a job-rich fiscal strategy.

Whatever the state of the external balance, a sovereign government can ensure that domestic demand is sufficient to fully employ the available workforce across a combination of these employment strategies.

There is never an excuse based on the external accounts for not implementing a Job Guarantee.

Under flexible exchange rates, balance of payments considerations should not be allowed to get in the way of deficit spending to achieve full-employment. A current account deficit merely indicates that foreigners desire to accumulate financial assets denominated in the domestic currency and are willing to ship more real goods and services (in aggregate) than they receive in return to accomplish this desire.

While the desires of the foreign sector may change over time, a fiat-issuing sovereign government under flexible exchange rates should not determine its net spending decisions (aimed at maintaining full employment) with reference to any particular foreign balance.

Further, there are ethical issues we pose with the argument that macroeconomic stability should be maintained by targeting the capacity of the poor to spend so as to address some external balance objective.

Should a nation attempt to maintain macroeconomic stability by keeping a portion of its population sufficiently poor that it cannot afford to consume?

Some argue in this context that by running expansionary fiscal policy, the external situation will lead to a depreciated exchange rate of some magnitude and this will make imports more expensive and reduce the standard of living of the nation. Here distributional issues are paramount in my view.

The unemployed, by definition, typically consume much lower volumes of imports. If we are saying that by providing jobs for all we make overseas ski trips and luxury imported cars a bit more expensive (marginally so) for the rich then that would seem to be an excellent trade-off.

More generally, I don’t consider unemployment and poverty to be acceptable policy tools to be used to maintain currency stability? Policy makers should accept some currency depreciation (if that is inevitable) in order to eliminate unemployment and poverty?

There are strong ethical arguments against using poverty and unemployment as the primary policy tools to achieve price and exchange rate stability. And even if currency stability is highly desired, it is doubtful that a case can be made for its status as a human right.

There is so much in the UNCTAD Report that I will finish this blog by noting their endorsement of public employment policies along the lines of the Job Guarantee.

They say that an effective way of dealing with large reserves of surplus labour (that is, unemployment):

… is to implement public employment schemes, such as those introduced in Argentina and India … which establish an effective floor to the level of earnings and working conditions by ensuring the availability of “on demand” jobs that offer the minimum employment terms. These terms should be improved over time at a rate that appropriately reflects the average growth of productivity in the entire economy and the increase in tax revenues in a growing economy. There are a number of benefits to such a scheme.

The benefits listed are several. First, the public employment scheme sets a standard of living floor because any worker can earn a socially-acceptable minimum wage. As such “it would ensure that employment outside the scheme would be on terms that are better than the minimum standards set by the scheme”.

This is a very important point. It means that the scheme fosters dynamic efficiency (productivity improvements over time) because it raises the bar for private sector job creation. Many low-skill private sector jobs which produce at high cost despite the low wages on offer would disappear and employers would have to restructure their work to allow them to pay higher wages in order to bid the workers away from the Job Guarantee when generalised aggregate demand was strong enough.

UNCTAD extend this as their sixth benefit:

.. by eroding the ability of firms to compete based on low wages and poor working conditions, it would help increase the share of formal sector employment in total employment, reduce the differential between the formal and informal sectors with respect to terms of employment, and improve the average terms of employment in the system as a whole.

So increase the overall productivity and real wage trajectories for all workers. That is a dynamically efficient path to international competitiveness rather than the doleful and flawed race-to-the-bottom approach that the austerians and neo-liberals in general advocate.

Second, “the demand for goods and services generated directly and indirectly – through a multiplier effect – by the scheme would help expand markets and drive output growth, so that the restraining effect of productivity increases on employment are neutralized by an enhanced pace of demand growth.”

This may or may not be a very strong effect depending on the gap between the support rate that is applicable to the unemployed and the chosen minimum wage. Where the gap is larger, the demand stimulus coming from the employment will be greater.

This point also allows us to understand that the true cost of the program is not the nominal outlays that the national government makes in setting it up and running it over time. Those numbers are not costs.

The costs are the extra real resources that are consumed by the now employed workers who are able to enjoy a higher standard of living. The other real costs are the capital equipment that might be used.

But in a period where there are huge volumes of idle productive resources (labour and capital) the opportunity costs involved are likely to be low given their alternative use is total waste.

Third, “the scheme itself would tend to be self-selecting, since only those unable to obtain this minimum level of wages and working conditions would demand and be provided with such employment”.

We can think of this as the limits of the fiscal policy in this regard. What would be the outlay necessary to ensure everyone who is idle and wants to work has a job (in the JG)?

Answer: the last person who walks through the Job Guarantee door sets the scale of the scheme. If these programs are truly self selecting, that is, are demand-driven rather than supply-driven, then they become automatic stabilisers. The expand and contract in a strict counter-cyclical fashion which is one of the features that an effective fiscal policy should possess.

UNCTAD list this as their fifth benefit:

… the scheme would act as an automatic stabilizer of consumption demand in periods of recession or downswing, and therefore serve to moderate the economic cycle, which is extremely important given that such stabilizers are relatively few in most developing economies.

The other important feature of creating such capacity in a nation is that it provides employment opportunities for the most disadvantaged persons. These persons have been excluded and alienated by the current neo-liberal policy paradigm which emphasises supply-side responses to unemployment (that is, deregulation, welfare cuts, etc).

Fourth, where there was a net gain in aggregate demand (directly and through the multiplier) the Job Guarantee would “ideally, reduce workers’ demand for such employment over time, so that there would be endogenous limits on the budgetary outlays needed to implement this policy”.

As if the budget outlays matter for anything other than political reasons. There is no financial constraint on a sovereign government running such a scheme. It can “afford” to buy all labour that is currently sitting idle at zero bid (that is, no other employer is bidding for the latent services).

I would caution people in thinking that the introduction of a Job Guarantee inevitably increases aggregate demand. This is a common misconception that even progressive economists make. It may or it may not. The point is that increasing aggregate demand is not the priority of the program.

In a paper with my colleague Randy Wray which was subsequently published in 2005 in the Journal of Economic Issues we considered this question. You can download a working paper version for free here – In Defense of Employer of Last Resort: a response to Malcolm Sawyer. As it happened that paper created quite a kerfuffle among progressives!

Finally, UNCTAD say that:

Public sector employment schemes can be successfully implemented even in very low income countries. In Sierra Leone, one of the poorest countries in the world, a World Bank supported public works programme after the disastrous civil war prevented thousands from suffering starvation. In 2008-2009 the government extended this programme as a measure to counter the international recession that reduced demand for export crops. The success of this programme demonstrates that emergency and countercyclical public employment schemes can play an important role even when administrative capacity is limited.

There is much more I can write about this. I have first-hand experience as a consultant working with such programs in South Africa and appreciate the difficulties in the design and implementation of them.

But when it comes to creating inclusive work which materially reduces poverty and imparts dynamically efficient forces into the wider economy there is no other option.

The implementation of a Job Guarantee should be the first policy that any sovereign government announces.

You may like to read or review the blogs that this Job Guarantee search string lists for further information. These blogs contain very detailed information about how the program would work and its optimal design characteristics.

Conclusion

I will provide further thoughts and analysis of this excellent Report over the coming week or so. For now I have run out of time.

Remember – 1 child dying from a lack of food every six seconds.

That is enough for today!

So what’s your take on Japans epic effort to devalue the Yen to simulate exports invariably creating a race to the bottom of the currency barrel?

Johnno,

You can’t buck game theory. Each nation will look after itself, and the politicians will look after themselves. That’s just human behaviour.

The key is to harness the essence of that human behaviour in a system that moves everybody forward.

Let’s see if I can apply anything I learned anything today.

US prints some monopoly money and exchanges it for Yuan. Just enough for the Chinese workers to buy a few bowls of rice. They ship some components to China and recieve loads of Ipods in exchange. The Americans quietly print some extra monopoly money, award it to themselves and buy Ipods. The Chinese put their US monopoly money into US treasuries which loses purchasing power over time. Why? to keep the Yuan low and the wages of Chinese workers low. It keeps Chinese in employment but on balance it looks a better deal for the US.

US prints some monopoly money and exchanges it for Euro. Lots of Euro for German workers to buy lots of beer. They receive an overpriced BMW in exchange. They still print extra monopoly money, award it to themselves and buy BMW’s. This crafty Germans use their US monopoly money to buy Ipods. They don’t keep a hold of the US monopoly money and they don’t really care how much the US prints. That looks a good deal for the Germans. If they are worried about competetiveness, they could quietly subsidize BMW to keep the game rolling on.

A well managed export of expensive luxuries sounds good. Providing labour services at lowest cost sounds a bad idea.

I can see it makes sense for a developing country to run a deficit to boost internal demand and keep the currency competetive. The nature of the export trade also seems very important.

Hi guys,

I am hoping someone can help me out with the following scenario. MMT states that:

“The non-government sector cannot create or destroy net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue. Anyone who says otherwise is not understanding how the system functions.”

What happens if a commercial bank becomes insolvent?

My understanding is that when a client defaults on his loan the asset and liability disappear off the balance sheet and the banks writes off the principal that wasn’t recovered absorbing it from its own equity. What happens if in a recession the bank goes under from writing bad loans and the losses cant be absorbed out of its equity? Wouldn’t this destroy financial assets in the currency of issue?

Probably a silly question but trying to get my head around it.. Many thanks for any reply.

Neil – the world pretty much appears to be on a race to the bottom of the currency barrel to stimulate their exports which is of course a sovereign right. If I understand Billys post, this is not going to have the desired effect and could potentially have an adverse outcome. Given the strength of the AU$, there’s a good chance that we’re going to get caught in a currency crossfire as major exporting nations debase their currencies to stimulate exports. So who’s going to be next? Let the winner be the one who devalues the most. I’d be interested to get Billy’s opinion on this event and the likely ramifications.

I’ve been following this for a couple of months now.

Early on it reminded me of Amartya Sen’s Economic Development work on famine where the issue isn’t so much the lack of food, but the catastrophic fall in income for labourer’s laid off by landowners due to the lack of crop to harvest. Not only was there a shortage of food and price increases, they lacked the income to buy it too. Although food production per person was lower in India than in Africa, the democratic Indian famine relief programme ensured food distribution enough to prevent starvation, though not necessarily malnutrition.

Ironically the budget surpluses destroy/reduce private saving/wealth argument reminds me of Soviet Communism’s inter-war destruction of private farming, surely this is something that should make right of centrists think twice or more?!

Bill,

Another excellent post.

You made reference to a currency’s exchange rate above, and it’s effects on prices of imported goods. I assume that what you say about an equitable trade-off is true as it seems to make sense:

“The unemployed, by definition, typically consume much lower volumes of imports. If we are saying that by providing jobs for all we make overseas ski trips and luxury imported cars a bit more expensive (marginally so) for the rich then that would seem to be an excellent trade-off.”

Many people also use claims of exchange rate issues to argue that governments should only “borrow” to match their deficit spending. To help persuade them otherwise I would be interested to see a summary of what factors actually affect exchange rates and to what degree.

There needs to be a relatively simple explanation to answer ordinary peoples’ concerns about “debasing” or “devaluing” the currency, when governments spend without issuing debt.

Kind Regards

Charlie

Damien: I’ll have a go at answering your question (and will fall ar*se over t*t in the process, probably).

I think the phrase “financial assets denominated in the currency of issue” is a fancy way of describing monetary base, or central bank created money. The bust bank’s reserves (i.e. its holding of monetary base) will effectively be distributed to the bust bank’s creditors thus that chunk on monetary base does not disappear.

(To be more accurate, the administrators would pay a sum of commercial bank created money to the creditors, and in turn, the same sum would be shifted, in the central bank’s books from the administrator/bust bank’s account to the accounts of the creditors’ commercial banks.)

In contrast, if the bust bank has recently extended me $X of credit, that is commercial bank created money. And if I think I still have $X in my account, then I’m probably in for a shock. That $X would disappear if the bank was totally and completely bust. Alternatively if the bank was salvageable, my $X might survive.

“There needs to be a relatively simple explanation to answer ordinary peoples’ concerns about “debasing” or “devaluing” the currency, when governments spend without issuing debt.”

The government always issues debt when it spends. A fifty pound note is debt, a bond if you like. The difference is that it is a permanent bearer bond that doesn’t need servicing with constant interest payments and that means we can spend more money on important stuff.

(Near enough for use in interviews as anti-spin)

“Unemployment is the largest source of poverty and starvation so that should always be our policy priority – virtually without regard in my view.”

I have always relied upon the suffering of others. (Apologies to Tennessee Williams.)

UNCTAD: “a premature exit from demand-stimulating macroeconomic policies aimed at fiscal consolidation could stall the recovery.”

Par’n my iggerance: “fiscal consolidation”??? What is being consolidated, and how? Thanks. 🙂

CharlesJ: “There needs to be a relatively simple explanation to answer ordinary peoples’ concerns about “debasing” or “devaluing” the currency, when governments spend without issuing debt.”

One, who says that spending without issuing debt devalues the currency?

Two, ordinary people understand that if you don’t issue debt, you don’t have to pay the interest on that debt. Ordinary people view the question of sustainability as principally one of exorbitant interest.

Why shouldn’t we have money without having to pay interest on it? 🙂

—-

On another blog a while back, I commented that if debt was the problem, why not create money without issuing debt? An economist replied that doing so would leave “excess money” in the economy. I asked if by “excess” he meant “greater than zero”. He did not respond.

Dear Johnno (at 2010/09/15 at 20:59)

One important point to remember is that Australia trades in primary commodities which are mostly priced in terms of $US or some other currency. Very few of our export contracts are denominated in $AUD.

Further, we do not compete as a trader of industrial goods which have much more stable prices.

That segments us a bit from the type of behaviour you are thinking about.

best wishes

bill

Dear Will Richardson (at 2010/09/15 at 22:18)

You said:

Even the entrenched right (other than those with irrational blind fears and loathing of government) do better when the government is using fiscal policy to support private income and wealth creation. Private firms would face lower hiring costs with an employment buffer stock system (Job Guarantee) relative to the current NAIRU system of price control (using unemployed buffers to discipline price). The middle class which is manipulated by the right to support anti-government policy agendas would also enjoy more stable wealth accumulation and not be threatened with bankruptcy from housing collapses and bad debts nearly as much.

And … while the centrists/right are less concerned about the plight of the lowest quintile … they also enjoy massive improvements in their standards of living. That has been demonstrated in countries I have worked in or studies when evaluating the impact of large-scale public works programs supported by social transfer systems.

So I agree – the right actually undermine their own best interest because they have been sold a dummy by the hard-core ideologues (who have wealth anyway mostly).

best wishes

bill

Dear Charlie (at 2010/09/15 at 23:23)

Thanks for your nice comments. I appreciate them.

You might like to start with this blog where I discuss the sort of issues you are interested in.

Modern monetary theory in an open economy

best wishes

bill

Dear Ralph (at 2010/09/15 at 23:56) and Damien (at 2010/09/15 at 20:09)

The reason I try to avoid using the term monetary base – although sometimes I do use it – is because it invokes the erroneous mainstream concept of the money multiplier. Changing the terminology helps de-condition our thought processes and educate us to think differently about the linkages. The term monetary base described (in the mainstream literature) the base upon which the money supply multiplied. The reality is of-course the opposite. The base (bank reserves etc) expand to meet the needs of private banks to hold reserves to ratify their lending decisions. The latter drive the former not the other way around.

Damien asks:

Yes it does destroy financial assets but not net financial assets. Both the asset and matching liability disappear.

Only government sector transactions with the non-government sector can create and destroy net financial assets in the currency of issue. It is crucial to understand that as the basis of a wider understanding of the way these transactions drive economic activity and support or curtail private sector activity. It is the starting point to learning macroeconomics although it is totally ignored by the mainstream textbooks.

best wishes

bill

Dear Min (at 2010/09/16 at 5:26)

The mainstream term “excess money” is highly misleading. I would not issue any public debt at all but I would continue to run budget deficits (generated by crediting bank accounts and/or issuing cheques) such that the growth in nominal aggregate demand was commensurate with the real capacity of the economy to respond to that spending by production.

That requires the budget should react to private spending fluctuations (which it does via the automatic stabilisers) and also that the government “manage” private spending so that it is consistent with the socio-economic goals that define the policy mandate that the government won office with.

Any extra spending above that is excessive. Any spending below that is deficient and will generate unemployment.

“Excesses” have to be seen in the context of the balance between spending and capacity. The fact that bank reserves are at record levels now given all the central bank balance sheet activity in the last few years is meaningless in terms of that balance. The stock of “money” only matters if it is being spent.

best wishes

bill

About the undernourished graph, one can only wonder how many of the about 200 million more from 2005 to 2009 should be put on Goldman Sachs and others hedge funds credit account when they drove up grain and oil prices artificially. Or how many of the children that die every six second because of undernourishment related problems.

bill: “The mainstream term “excess money” is highly misleading.”

Thanks. bill! 🙂

The expression seemed strange to me. Like any (more or less) permanent money would be considered excessive (!). That is why I replied as I did. When he did not reply, I figured that he did not have an explanation for the word. I had no idea that it was an actual term. 😉 I did not realize until today that he might have been offended. {shrug}

Min,

Sadly, ordinary people have bought into the neoliberal myth that unless a government “borrows” in order to deficit spend, then the sky will fall on our heads. For evidence of this – see both the UK and Australian election campaigns – and particularly the UK election result, where the Tories did very well by convincing everyone that the government were heading for the same fate as Greece – the puplic generally believed them.

If however you meant your comments as things I could say to other people – I’ve tried it and had some positive effect, but it is not really sinking in with people who only understand household accounts.

I’ll keep learning and trying though.

Kind Regards

Charlie

“Answer: the last person who walks through the Job Guarantee door sets the scale of the scheme. If these programs are truly self selecting, that is, are demand-driven rather than supply-driven, then they become automatic stabilisers.”

Great idea, but what exactly would you have the un/underemployed do? Sit in Government offices pushing paper or filing? Digging holes by the side of the road?

I wonder if there is enough infrastructure present to actually employ those who are underemployed.

What about the lazy element? Your analysis assumes that the underemployed actually want to be fully utilized to improve both their and society’s living standards.

Rather than employing AW’s rather bright idea of haircutting bond holders a few percent here and there (because they are supposedly ‘the rich’), why don’t thinkers like yourself appeal to nations to donate say 1% of their defence spending to such noble causes? Such a referendum would have far more chance of being publicly endorsed than trying to change capitalism to communism so that private assets can be nationalised and redistributed which seems the thinly veiled purpose of many of the arguments here.

Johnno’s comment intrigued me.

“So what’s your take on Japans epic effort to devalue the Yen to simulate exports invariably creating a race to the bottom of the currency barrel?”

Japan and Germany have all the bullets to be the absolute winner in currency games amongst OECD countries. Due to some internal political dogma they are holding back on the trigger.

They already have a high living standard and relatively high employment. Healthy demand for their high value add exports creates huge external demand for their currency. They can easily afford to run huge budget defits providing more jobs or infrastructure for their people. If by printing more money they devalue their currency, that just creates more demand for their exports. They can adjust their government spend and product prices to optimise their excess productive capacity.

I don’t see why they don’t just go on a gala Government spending spree and enjoy themselves to the fullest. There is no bottom to find. Just look for a happy balance to meet the socio economic goals of the people.

China appear to be the biggest mugs in the game, they are truly in a race to the bottom. Eventually they could be competing with Burkinso Faso. The amusing thing is, I was accosted by an Asian friend delighted China was one of the richest countries in the world in terms of foriegn currency holdings. He was laughing at the poor nations in the West. The Chinese policy just seems to tingle a bell with their savings culture.

CharleJ: “Sadly, ordinary people have bought into the neoliberal myth that unless a government “borrows” in order to deficit spend, then the sky will fall on our heads. For evidence of this – see both the UK and Australian election campaigns – and particularly the UK election result, where the Tories did very well by convincing everyone that the government were heading for the same fate as Greece – the puplic generally believed them.”

Iam not sure that we can draw that conclusion. I mean, a lot of people believe that the gov’t needs to borrow money for deficit spending. They don’t even face the question of what deficit spending without borrowing means. But, if they have gotten that far, one thing it for sure means is that you do not have to pay interest. 😉

Min,

It was not only fear of UK turning into Greece that tempted UK voters into the budget surplus camp. Boomers perceive their wealth will be protected better in a low inflation, stable price environment. I also believe the policy stance is favoured in the short term by the financial community.

The Tories also hinted they would be burning gypsy caravans. That’s always a vote winner.

Ray:

“I wonder if there is enough infrastructure present to actually employ those who are underemployed.”

When you say infrastructure, do you mean offices? Bureaucrats? Railway lines? Seems like all those can be solved simply with more hiring. Yes, non-JG people will be needed to administer and support the JG. But with plenty of talented people out of work, that’s not a problem. Just means for every 100 JG slots, there need to be a few high paying, quality jobs.

“What about the lazy element?”

The vast majority of people want to earn their money. The few who actually are parasites can be fired from the JG, maybe for a set period of time or whatever.

“change capitalism to communism”

Relax and stop trying to read sinister motives into everything. I personally see this as a way to make capitalism work much better. If we keep going down the path of frequently occurring recessions and constantly high unemployment, people might get fed up and think it’s capitalism’s fault. That makes it far likelier for some kind of red revolution to happen.

Think about it – where are the hotspots of civil unrest and rioting right now? In the countries that are pursuing hardcore neo-liberal agendas.

So really I see MMT as a way to save capitalism and turn it back into the vibrant, efficient system it was in the post war boom. I suspect that goal is shared by many of my “comrades” here.

Bill,

A great post.

I have tried to analyze the situation in Ireland based on your earlier analysis on my blog:

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2010/09/irelands-sham-recovery-gnp-versus-gdp.html

Also, have you commented on how Germany’s recovery Q2 2010 with GDP growth of 2.2% was basically based on Keynesianism in China:

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2010/09/germany-success-of-keynesianism-and.html

Keep up the good work!

Andrew

On the question of the EMU and the insights from MMT, the following occurred to me.

The Irish central bank/government has the power to issue debt and the power to enforce taxation independently from the European Central Bank.

So isn’t the solution simply to turn the debt into proper money, ie accept any issued Irish Bond at face value as settlement of taxation obligations. Doesn’t that then put a guaranteed floor under the entire Irish Bond market and solve the problem? It’s unarguable by the deficit terrorists because by definition it gets rid of ‘debt’ – and it would be mildly amusing watching them trying to explain it.

You could even go one step further and make them ‘legal tender’ so that they can extinguish bank debt obligations as well (which would satisfy those who think bank debt is the driver, not just taxation (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartalism#Criticism)

So what am I missing?

Dear Neil Wilson (at 2010/09/16 at 16:41)

This is exactly what a state like California could also do – just issue IOUs (warrants) and accept them in return for all state charges and taxes.

I wrote about that last year in these blogs:

California IOUs are not currency … but they could be!

My letter to the Governor (arnie)

In the EMU case, I am no legal expert though so there might be rules prohibiting these sensible ways around their nonsensical design.

best wishes

bill

In Oakland, CA, a relatively poor and liberal city across the bay form San Francisco, the idea is going around about a possible local currency. in the form of an Oakland ID/debit card. Oakland is not particularly “business friendly”, and a selling point for the currency is as a way to get people to spend money in Oakland. I don’t know the details yet. Sounds interesting. 🙂

“The FAO say that there is:

… a child dying every six seconds because of under-nourishment related problems …”

Dear Bill,

The real point is that every six seconds somebody misses out on a chance to be alive: live life, laugh and cry and enjoy – a 250,550 day chance given on average in the ‘developed’ world, to fulfil their heart.

Walking on the beach this morning, a beautiful green ocean and blue skies; the sun reflected in the wet sand reminding me that even with eyes cast down, there is light (understanding) if you look. I wondered if these numbats that focus on reporting death and misery in their Organisational Papers ever get outside and take their shoes off? How disconnected are these statistics from Nature? Once again it comes down to resources!

There is not a living creature on the face of this earth that does not know how to survive and thrive, given the right environmental conditions and resources – and demonstrate amazing adaptability. The monetary system has got nothing to do with it!

I have seen when people are given resources and a little know-how, they will come together, labour and produce food for their village; then the kids want to go to school because they can concentrate and enjoy it.

Here’s one little model drop of mercy I know of (12min) in an ocean of ignorance and fiasco: A Flame of Hope

Warm Regards,

jrbarch

Is it not possible to view export led strategies as a necessary part of a country’s development? Surely development implies the acquisition of new technologies, so a country initially selling low-value exports to obtain foreign currency to import the technologies it needs to develop can’t always be a bad idea?

This is part of my concern with the simplistic ‘exports are a cost, imports are a benefit’ argument. It seems to neglect the fact that exports can be an intermediate step in a bigger strategy.

Also, I am not sure about your comment “… the external situation will lead to a depreciated exchange rate of some magnitude and this will make imports more expensive and reduce the standard of living of the nation. Here distributional issues are paramount in my view. The unemployed, by definition, typically consume much lower volumes of imports.”

Is it really true that low wage earners and unemployed consume lower volumes of imports? A depreciated exchange rate will surely make the cost of imported oil and other commodities priced in dollars more expensive, and oil is used in some form or another by the entire economy.

houseman

I think if you read more of what Bill has to say about import/exports you’ll find he agrees with you that developing countries can benefit from being an exporter and can help to develop an economy. What I think he would say is that the neoliberal ideologues in the IMF are mistaken in their desire to saddle all developing nations into being exporters to the rest of the developed world. These strategies dont necessarily have the developing countries best interest at heart. His exports are a cost is a way to demonstrate that working to produce for others is what exporting is. Its fine to do that but understand what it is. Sometimes it seems the neoliberals really believe we can all be net exporters.