I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal austerity is undermining growth – the evidence is mounting

Remember what we were told a few months ago – that business and households were so terrified of higher future tax burdens associated with the budget deficits that they were not investing or spending and so governments were killing economic growth? This led to the deficit terrorists arguing (shouting) that the fiscal stimulus that governments had implemented to save their economies from the threat of a depression were actually undermining growth and that fiscal austerity was the key to growth. Accordingly, governments have increasingly been implementing or promising to implement so-called fiscal consolidation strategies because they have fallen prey to the austerity proponents. As the fiscal stimulus has waned across the world growth is slowing and there is now a real danger of a double-dip recession. In nations that have introduced formal austerity programs the evidence is now mounting … it damages growth and undermines business and household confidence. It has exactly the opposite effect to that predicted by the deficit terrorists which is no news to anyone who understands anything about how the economy works. The victims – the poor and disadvantaged …. AGAIN!

Recall the coverage I gave the CEO of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, Richard W. Fisher in this blog – The old line back to free market ideology still intact. Fisher gave a speech gave a speech entitled – Random Refereeing: How Uncertainty Hinders Economic Growth in July where he perpetuated the view that the deficit terrorists are now vehemently pursuing that government policy is making the recession worse and things would be better if the government cut its deficit and allowed the private markets to resume spending and growth.

Fisher provided the representative conservative viewpoint when he said that:

I have ascribed the economy’s slow growth pathology to what I call “random refereeing” – the current predilection of government to rewrite the rules in the middle of the game of recovery. Businesses and consumers are being confronted with so many potential changes in the taxes and regulations that govern their behavior that they are uncertain about how to proceed downfield.

At the time I wrote that much of the “uncertainty” is being driven by the fact that the government stimulus is now being withdrawn and austerity programs which are cutting peoples’ incomes and pensions are now being pursued with vigour.

Fisher claims that the current fiscal situation is crowding out private spending, making it impossible for the US government to deal with the recession (because they have run out of money) and hindering the capacity of “individuals to smooth their consumption over the business cycle” and raising the “probability of a debt crisis”.

Underpinning of the crowding out hypothesis is the old Classical theory of loanable funds, which is an aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

Mainstream textbook writers (for example, Mankiw) assume that it is reasonable to represent the financial system to his students as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consequences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

The erroneous mainstream logic claims that investment falls when the government borrows to match its budget deficit – the borrowing allegedly increases competition for scarce private savings pushes up interest rates. The higher cost of funds crowds thus crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. This leads to the conclusion that given investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

It is clear that governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

But the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes (real) interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

Further, from a macroeconomic flow of funds perspective, the funds (net financial assets in the form of reserves) that are the source of the capacity to purchase the public debt in the first place come from net government spending. Its what astute financial market players call “a wash”. The funds used to buy the government bonds come from the government!

There is also no finite pool of saving that is competed for. Loans create deposits so any credit-worthy customer can typically get funds. Reserves to support these loans are added later – that is, loans are never constrained in an aggregate sense by a “lack of reserves”. The funds to buy government bonds come from government spending! There is just an exchange of bank reserves for bonds – no net change in financial assets involved. Saving grows with income.

But importantly, deficit spending generates income growth which generates higher saving. It is this way that MMT shows that deficit spending supports or “finances” private saving not the other way around.

Finally, the consumer smoothing argument is based on the Ricardian Equivalence nonsense that I have blogged about regularly. Please read my recent blog – Defunct but still dominant and dangerous – for more discussion on this point.

It gets worse …

More recently, the right-wing Bloomberg columnist and Director of economic-policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, Kevin Hassett ran the same line in his recent rant (August 23, 2010) – Bury Keynesian Voodoo Before It Can Bury Us All.

He notes that US unemployment continues to rise and:

Incredibly, some Keynesians who supported Barack Obama’s $862 billion stimulus now claim it fell short of their goals not because the idea was flawed, but because the spending package was too small … The notion that a much-larger U.S. stimulus would have been more successful isn’t backed up by evidence. Maybe there would be an argument if some countries were now booming because their stimulus packages were larger.

The fact is, the U.S. stimulus was the largest among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the biggest ever tried in the U.S.

Hassett might usefully check out what the Chinese Government did. They provided a very significant fiscal stimulus which was around the same relative size as the the US injection but was more focused on spending rather than revenue measures. A dollar of tax relief is less stimulatory than a dollar of direct spending because some of the tax relief is saved.

The US economy also has relatively small automatic stabilisers because it has “less extensive social benefits (unemployment insurance, training), particularly compared with Europe.” (Source: IMF). So it needed a larger discretionary stimulus

In relation to the role China has played in the recession, the OECD boss Angel Gurria delivered a speech on March 23, 2010 – The OECD, the World Economy and China. He noted that:

China’s economy has outperformed all expectations, both over the long haul and, more recently, during the global Great Recession. China bounced back promptly thanks to the effective monetary and fiscal stimulus. Chinese demand is helping to support the global recovery. Actually, one third of the world’s growth this year will be attributable to China’s double-digit expansion, which will ease slightly next year, as the gradual withdrawal of monetary and fiscal stimulus outweighs the impact of stronger external demand.

The issue was also analysed by the IMF in 2009 and they summarised their findings in The Size of the Fiscal Expansion: An Analysis for the Largest Countries. The IMF made two important points that Hassett might reflect on:

The magnitude of the overall fiscal expansion – discretionary and nondiscretionary components – should depend on the size of the output gap that each country faces in the absence of fiscal support … [and] … The fiscal expansion in a particular country should be larger if multipliers are lower.

The IMF found that the “deterioration in the growth outlook in the U.S. has been among the most severe in the large G-20 countries, starting earlier than elsewhere and with a greater effect on labor markets. Japan, the U.K., and Canada have also experienced a significant widening of output gaps”.

Further, the IMF found that the US also has a lower expenditure multiplier (as does the UK) compared to other nations they examined.

So merely comparing the size of the fiscal stimulus by nation (even if you use relative scaling by GDP) is unlikely to be very helpful. Just because the US had the largest stimulus and the largest in its history (which is questionable) means nothing. They also had the largest output gap and the induced consumption effects are measured to be lower for every new dollar exogenously injected.

Further, because of the stronger ideological bias in the US towards markets and individuals the proportion of tax cuts in the fiscal stimulus has been much higher there so the “leakage” has been higher.

Hassett might like to read the OECD interim assessment of the The effectiveness and scope of fiscal stimulus which certainly doesn’t match his conclusion. That assessment shows that the fiscal stimulus certainly helped the US economy avoid a worse downturn and also stimulated renewed growth.

The OECD Report showed that the top two nations in terms of size of stimulus were the US and Korea with Australia in third place as a percent of GDP. However, significantly the OECD data shows that the direct government spending component of the stimulus relative to tax cuts was the highest in Australia compared to all other OECD countries.

Australia avoided a technical recession altogether and fortunately contained the rise in unemployment because its spending impulse was superior to the mix of spending and tax cuts.

Hassett might also like to catch up with the paper – The Effects of Fiscal Stimulus: A Cross-Country Perspective – which was published by the US Council of Economic Advisers. It found statistically significant relationships between fiscal stimulus and the extent to which economic outcomes exceeded forecasts and was published on September 10, 2009.

The US CEA paper found that:

The evidence suggests that countries that did larger stimulus in 2009 had better GDP performance in the second quarter of 2009 than would have been expected. The relationship between “beating expectations” and stimulus looks even stronger when the sample is limited to OECD countries (where the economies are more similar) … the basic idea – countries that did more stimulus saw better performance – survives multiple robustness checks.

He might like to be warmed by the idea that similar results have been found in Australia by the Commonwealth Treasury

Hassett then makes the claim that:

Nor does the academic literature support what we might call these Not-Enough Keynesians.

He chooses to cite one 2002 article from the IMF – Fiscal Policy and Economic Activity During Recessions in Advanced Economies – which he says finds from past experience that “increased spending by government had, in almost all cases, a barely noticeable impact, and sometimes a negative one”.

While that paper is highly flawed in its research design, it does not tell the same story that Hassett would like his readers to believe. It concludes:

However, these conclusions do not preclude the possibility that, where the circumstances are right, fiscal expansions can be an effective response to a recession. The right circumstances would feature some or all of: excess capacity … expenditure-based fiscal policy; and an accompanying monetary expansion.

They find positive spending multipliers and an “implausibly large effect of crowding out” in their models, the latter they choose to disregard. Implausible means not to be believed.

I conclude that Hassett’s use of this paper is deceptive in the extreme.

He also acknowledges – without knowing it – that his earlier claim that the US stimulus was the largest in the OECD and still unemployment rose – was misleading. He later admits that:

The so-called tax cuts in the 2009 stimulus had little effect because they were primarily credits and deductions, rather than reductions in marginal rates.

So the effective fiscal stimulus was much lower for reasons noted above – multiplier parameters and the design of the intervention.

Before anyone can reasonably conclude that the fiscal policy was damaging they would have to address all these issues. It turns out that the US fiscal stimulus, given the limitations in its design and the fact that its output gap was much larger and its multipliers probably lower, was a great success.

The evidence supports the “Not-Enough Keynesian” argument which I prefer to call the Not-Enough MMT argument.

Hassett concluded:

In all likelihood, the data will soon be so convincingly bad that we’ll again debate the need for an economic stimulus. Let’s hope that when that begins, all will finally concede that the ideas of John Maynard Keynes are as dead as the man himself, and that Keynesianism is the real voodoo economics.

The data does remain bad – the real data – employment growth, GDP growth etc – and there is a crying need for further fiscal stimulus concentrated on spending and in areas that will deliver job-rich dividends. The introduction of a Job Guarantee would be a great place to start.

And despite what the shonky right-wing ideologues like Hassett care to admit, all the evidence from the IMF, the OECD, national treasuries, and other large research organisations around the world is pointing in the same direction – the fiscal interventions saved the world from a much worse calamity that would have beset us if the conservatives had have held sway.

Please read my blog – Fiscal policy worked – evidence – for more discussion on this point.

Some months into austerity and the evidence is coming in …

In June, I wrote this blog – Fiscal austerity – an interesting test is coming – in response to the growing call for fiscal austerity from the deficit terrorists.

I wrote that the coming period will be an interesting test given the widespread acceptance by politicians around the world that fiscal austerity is good for growth. Governments are increasingly getting bullied into adopting austerity measures apparently thinking they will help their economies grow. My bet is that the austerity measures will undermine growth and when growth finally returns it will be tepid and as a result of other factors not related to the austerity.

While Ireland is already showing the way – the austerity has badly damaged growth in that economy, the UK is a good test case of a truly sovereign nation – one that issues its own currency and floats it freely on international markets. It embarked on its madness after the Labour government was toppled in May.

It is still too early to gauge the full destructive impacts of the stimulus and they will be revealed towards the end of this year. But the evidence is now coming in strongly to support the MMT contention that austerity damages growth. The evidence is further testament to the mad antithetical conclusions of the deficit terrorists.

The first strong piece of evidence comes from the ICAEW/Grant Thornton UK Business Confidence Monitor (BCM) for the third quarter 2010, which is published by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales ( ICAEW ) and a UK accounting firm.

You can get the full Report HERE.

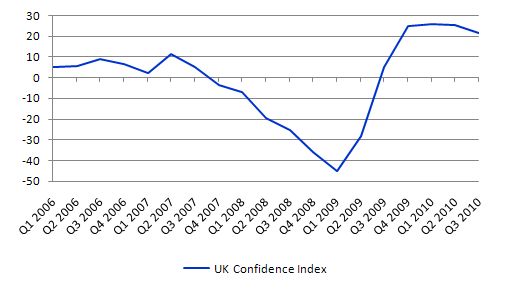

The following graph is produced from the data appendix that the ICAEW supply. It shows the course of business confidence from the first quarter 2006 to the third quarter 2010. You can see how the fiscal stimulus helped the index recover after taking a beating during the downturn. As the talk of fiscal retrenchment mounted the index has now started to head south again.

In the summary statement accompanying the Report we read:

Business confidence has weakened significantly as businesses acknowledge the path to recovery contains further challenges, with a fast return to strong growth by no means guaranteed.

Pity about that. Firms care about how much they can sell. They will not increase production or build new capacity while the state of future aggregate demand remains uncertain. They do not want to hold unsold inventories.

What drives production and employment growth is aggregate demand growth. Implementing fiscal austerity undermines the very foundation of this growth. It is an act of a vandal when private spending and confidence is low. It is no surprise at all that the fiscal austerity would damage private sector confidence.

Only the deficit terrorists who live on another planet would dare to argue otherwise.

The Report makes it clear where the blame lies:

Currently the UK economy is running at more than 4% below pre-recession levels. The public sector cuts outlined by the new Government and consequent reduction in public sector demand will have a significant downward effect on growth, constraining take up of spare capacity as the private sector recovers.

Okay! That is totally what a person who understands how the monetary system (including the production sector) operates would predict. No surprises there at all – sorry to say.

The other piece of evidence come from the latest (August 23, 2010) YouGov and Markit household finance index which shows that pessimism is now “greater than at any time since the end of the recession”.

Among the key points of the results were:

- Household Finance Index (HFI) rooted inside negative territory as economic upturn fails to deliver improved income and job security.”

- Sharpest drop in private sector job security for 13 months … suggesting the impact of government spending cuts has reverberated beyond the public sector.”

A Markit economist commented saying that:

Stronger growth in the UK economy has done little to put a floor under the downturn in household finances. A downbeat mood spans the household income spectrum, but remains most acute amongst the lowest earners. Household finances continue to suffer from a backdrop of squeezed disposable income, stubbornly high inflation and ongoing public sector spending cuts. Meanwhile, job security in the private sector fell at the fastest rate for thirteen months, suggesting that the renewed bout of employment concerns has reverberated beyond the public sector.

The growth was the result of the fiscal stimulus which is now being harshly withdrawn. So the evidence is supporting the view that expectations are that the austerity policies will damage job prospects and households do not feel confident in spending.

This is exactly the opposite to what the deficit terrorists predicted. It will get worse into 2011.

The UK Guardian reported the results in this way:

Fears about job cuts, rising prices and a weak housing market are making Britons ever more gloomy about their household finances, a report published today says. With big government spending cuts on the horizon, public sector workers remain particularly nervous but the worries also appear to be spreading to the private sector …

There is also news from the UK that the property market is in decline again as the pessimism spreads.

So where are all those Ricardian households and business firms that the conservatives tell us are just desperate to spend if only the budget deficits will be tamed?

Answer: in the land of myths.

Conclusion

Solution: these vandals should be tried for crimes against humanity and meanwhile governments should increase their fiscal support for the ailing economies to push them into positive growth and to engender some optimism.

The claim that consumers and business investors are paralysed by the state of public finances has never been empirically supported unlike the alternative that firms care about the state of the orders coming into their businesses and households care about the likelihood that they will hang onto their jobs and enjoy some real wage growth.

That is enough for today!

Bill says: “The US economy also has relatively small automatic stabilisers because it has ‘less extensive social benefits (unemployment insurance, training), particularly compared with Europe.’ (Source: IMF). So it needed a larger discretionary stimulus.”

Very good point! I came across a paper “Automatic Stabilizers and Economic Crisis: US versus Europe” published by NBER (It’s gated. I’ve no idea whether it’s prohibited to upload it to my webspace for download? Will a NBER SWAT team storm my place?) It says:

“We find that automatic stabilizers absorb 38 per cent of a proportional income shock in the EU, compared to 32 per cent in the US. In the case of an unemployment shock 47 percent of the shock are absorbed in the EU, compared to 34 per cent in the US. This cushioning of disposable income leads to a demand stabilization of up to 30 per cent in the EU and up to 20 per cent in the US … We also investigate whether countries with weak automatic stabilizers have enacted larger fiscal stimulus programs. We find no evidence supporting this view.”

A difference of 10% is huge. They further conclude “These results suggest that social transfers, in particular the rather generous systems of unemployment insurance in Europe, play a key role for demand stabilization and explain an important part of the difference in automatic stabilizers between Europe and the US.” The whole enterprise “Let’s-beat-up-the-Keynesians” is based upon cherry picking scant obscure evidence and filling the remaining void with some ideological fairy-tales and whishfull thinking.

Bill,

I’ve been meaning to ask this for a long time, it’s probably better suited to other threads, but I thought it inappropriate to expect you to trawl through archives.

With your resistance to austerity programs, it appears you seek to maintain prior levels of aggregate demand.

I would like to ask in a society where there has been (debt fueled) speculation, and as a result a misalloaction of resources that we commonly see in a boom/bubble, without a contraction of demand, how do you propose sectors that have been overallocated resources adjust back to more sensible levels?

In the absence of a shock via price or demand, it isn’t reasonable to expect them to self-adjust downwards.

Cognitive bias would usually have such participants feel entitled to continued price and demand levels.

The Residential Property industry in Australia is a prime example.

Bill,

” A downbeat mood spans the household income spectrum, but remains most acute amongst the lowest earners. Household finances continue to suffer from a backdrop of squeezed disposable income, stubbornly high inflation”

I have heard the mention of high inflation in the UK at present quite a few times now. Given the situation that the UK economy is in, what could possibly be driving such inflation?

We have deficits that are now greater than 9% of GDP. And you want to add to that? That is insanity, not fiscal policy. IMHO we are giving the patient enough medicine to kill it, not save it.

In a few years we will look back on this and conclude that QE-2 and the unending stimulus was the worst policy option. These things have outlived their usefulness. They will destroy everything that we once held dear. You really want more of that?

Lefty,

“what could possibly be driving such inflation?”

When Darling put VAT back up to 17.5% it raised CPI by about 1.5%. This effect would run-off by January 2011, except that the coallition will then raise VAT to 20%! So, it’s being caused directly by the austerity measures in this case. If you strip out changes to VAT and duties (the CPIY rate shows this), CPI would be about 1.4%, well below target, and heading down.

Kind Regards

Charlie

Cmon Bill, you don’t expect the AEI to ever…possibly….conceivably….just plain ever……adhere to the context of a research paper, do you? Accuracy and consistency aren’t part of the mission statement.

“Further, the IMF found that the US also has a lower expenditure multiplier (as does the UK) compared to other nations they examined.”………is that because the skew in the US has tended to be tax cuts to the highest earning percentiles?

“Australia avoided a technical recession altogether and fortunately contained the rise in unemployment because its spending impulse was superior to the mix of spending and tax cuts.”………..geez, you wouldn’t know that from the re-election strategy chosen in the last month!

@Bruce

Before crying wolf about federal deficits I would suggest you make yourself familiar with some basic economic principles, which will hopefully calm you down and lower the alarm level to “no danger here”.

Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Bruce . . .you offered absolutely no argument as to why the stimulus is bad . . just that it is. Of course, Bill noted in yesterday’s post that the US stimulus was very poorly targeted, so “more” stimulus isn’t necessarily needed as much as “better” stimulus. Also, several have already shown that given cuts at state/local levels, net stimulus from the federal level was quite small. And why is QE2 harmful? It won’t work because QE is a misnomer, but it’s not necessarily harmful aside from replacing coupon interest received by the private sector with interest on reserves.

Bill,

I second Aaron’s question, I tried looking through the archives for a place you mentioned the liquidation of misallocated resources, how does that happen in the MMT framework?

Thanks

@Scott:

“it’s not necessarily harmful aside from replacing coupon interest received by the private sector with interest on reserves.”

I would guess that Bruce doesnt really understand this statement, and/or it’s relevance, I wish he and many others would take the time to get into it and really understand these operations. This would really go a long way to eliminating much political opposition to what would be more helpful fiscal policies.

Resp,

This may have fit better with yesterday’s comments, but I spent a day thinking it over….

I was thinking about asset prices, for things like stocks and real estate. These are not consumed, and creation of more assets doesn’t follow simply from a price rise, so their supply/demand curves aren’t like those for a typical consumption good. Further, their very reason for existence is different — to the owner, they’re a form of savings, a store of value.

Then yesterday’s blog was about distributional effects, and in particular the portion of the Bush tax cuts aimed at the very wealthy. Bill made the excellent point that such tax cuts have relatively little stimulatory effect because the wealthy have a low marginal propensity to consume. But they have a high marginal propensity to buy assets. If you give a billion dollars to poor or middle-class people, they’ll largely spend it on consumption, adding to aggregate demand. And the fraction they save will largely be in the form of debt reduction rather than asset purchases. If you give a billion dollars to rich people, they’ll bid up the price of stocks.

And then I started thinking about some longer-term trends here in the US. A couple of things have changed in the last 30 years or so. (1) Monetary policy has triumphed over fiscal policy as the economic tool of choice for regulating the business cycle. (2) Tax policy was made far more favorable to the wealthy, particularly under Reagan and Bush II and including not just income tax rates but cuts in capital gain rates and increases in Social Security rates. (3) Manufacturing has become increasingly globalized, and a smaller share of US GDP. (4) The gains due to rising productivity ceased to accrue to workers — median wages have been stagnant — and went almost entirely to capital owners. Thus there has been rising inequality. (5) The business cycle has switched from a manufacturing/inventory cycle to an asset bubble/bust cycle.

It seems to me that 4 (stagnant median wages) has been driven by some combination of 2 (tax policy changes) and 3 (globalization of manufacturing). Now I’m wondering if the changing nature of the business cycle, which I had previously attributed almost entirely to the de-emphasis of manufacturing in America’s GDP, also has significant roots in the regressive changes to our tax system. Would a more egalitarian society, with capital distributed among a larger portion of the population, be less subject to asset bubbles? Would higher tax rates on capital gains dampen the bubble/bust cycle (both by discouraging speculation on rising prices vs. investing to obtain a predicted dividend stream, and by being counter-cyclical, draining private spending power when asset prices do rise)? And what role does monetary vs. fiscal policy play?

At the rate the Neo-liberals are going we will run out of straw.

Thanks for that Charlie.

As a non-economist, it still seemed pretty bizzare to me for the UK to be experiencing inflation while consumer demand is weak. I knew there had to be an explanation.

I would say, watch as this is now used as “proof” to perpetuate the fallacy that sovereign government spending requires revenue from taxation.

Aaron: Your point is classic Austrian / von Mises. I only half agree with it.

Obviously given a significant misallocation of resources (ninja mortgages etc), restructuring is needed. But restructuring takes place all the time, even in non recessionary scenarios, i.e. at full employment. That is, firms are constantly go bust while others expand even at full employment.

I.e. my hunch is that the restructuring currently required does not warrant the current high unemployment levels. For example most U.S. unemployment is caused by damaged private sector balance sheets, and the consequent collapse in demand from the private sector – it’s not caused primarily by the fact that employers cannot find the skills they want because millions of Americans have acquired to the wrong skills due to the above misallocation.

Bill,

If you ever need a proof that Austrians are clueless you can waist your time with a recent paper of Arnold Kling “Guessing the Trigger Point for a U.S. Debt Crisis”. I just had a very brief look. It’s funny and starts with a joke. He compares the US government to someone who owns a credit-card. Of course he references RR.

Aaron: Your point is classic Austrian / von Mises. I only half agree with it.

Obviously given a significant misallocation of resources (ninja mortgages etc), restructuring is needed. But restructuring takes place all the time…

Ralph … appreciate your comments, but I’d love to see expanded critique of the Austrian theory of the business cycle, since I hear these notions all the time (the commentators not necessarily being aware of where they come from) . Is there a related blog in the archives somewhere?

Ken

Ken asks:

“…I’d love to see expanded critique of the Austrian theory of the business cycle, since I hear these notions all the time (the commentators not necessarily being aware of where they come from) . Is there a related blog in the archives somewhere?”

Here’s an old article by Krugman, referenced today on his blog, that covers the ground pretty well:

The Hangover Theory

http://www.slate.com/id/9593

“…A few weeks ago, a journalist devoted a substantial part of a profile of yours truly to my failure to pay due attention to the “Austrian theory” of the business cycle-a theory that I regard as being about as worthy of serious study as the phlogiston theory of fire. Oh well. But the incident set me thinking-not so much about that particular theory as about the general worldview behind it. Call it the overinvestment theory of recessions, or “liquidationism,” or just call it the “hangover theory.” It is the idea that slumps are the price we pay for booms, that the suffering the economy experiences during a recession is a necessary punishment for the excesses of the previous expansion.”

Dave ….

Liked that article.

Thanks.

Ken

Scott

Dont hold your breath waiting for Bruce to actually make an argument. Bruce is a bond trader and wants to save us from ourselves by getting a better return on his bonds. He thinks interest rates need to rise so his work free income can be higher. He’s not interested in us issuing less debt he just wants debt with a better return thats all. He thinks if him and all his buddies threaten to hold their breath til they turn blue the govt will capitulate and give him better returns. It might work, but he aint doin’ it for the sake of the countries financial position, just his own.

With my apologies to all, especially Bill, I see that there is movement on the inter-webs on the subject of MMT, at least as to what exactly it is. Or, maybe not exactly.

Me thinks videos are needed.

http://www.youtube.com/user/TheModernMystic#p/u/3/rlHUiEcPD6U

It must lead some questioners here.

The Money System Common

Ralph, thank for your reply.

I’ll query more if I can

“Obviously given a significant misallocation of resources (ninja mortgages etc), restructuring is needed. But restructuring takes place all the time, even in non recessionary scenarios, i.e. at full employment. That is, firms are constantly go bust while others expand even at full employment.”

I agree they do, but rarely, if ever, in a sector wide adjustment of supply. Firms going bust in a time of full employment is usually a lack of demand for their specific product, as customers go a a competitors product. Other forms of restructuring appear to be internal reform to increase productivity in an effort to increase market share or marginal return.

I can’t recall any example of an entire sector voluntarily retract its activity as to prevent economic instability. In fact I propose that game theory says they will not.

“I.e. my hunch is that the restructuring currently required does not warrant the current high unemployment levels.”

I’d say the barriers to preventing the pace of restructuring, and policy response has inhibited suitable private sector restructuring. I have a $1 coin in my pocket with no debt or liability secured against it. it is my personal ‘CBA collapse fund’. If and when the Commonwealth Bank collapses, I will immediately offer a bid of $1 to buy allof the CBA’s assets and repudiate all of tis debts. As an ongoing concern it can potentially be my corporations. If someone wants it more than me, they will bid 42, and so on until we get a final market clearance price.

I do not want government interferring by saving the bank, or more accurately, the existing managers and equity holders of the bank, and I would like the process to be immediate. If it happens quickly, then I will guarantee no bank teller, no analyst, etc will lose their jobs, thus there will be no social dislocation.

All that happens is that debtors, depositors and equity holders lose their money, and the latter 2 paid good money for their executives manage their money effectively, but hey, that’s agency theory.

“For example most U.S. unemployment is caused by damaged private sector balance sheets,”

Bankruptcy is a method of repudiating debt and repairing balance sheets, via existing assets transferrring to new owners. New owners, such as me with the CBA, will seek to root out bad practices and poor performing managers. I feel maintaining demand will entrench poor managers and poor practices.

“and the consequent collapse in demand from the private sector – it’s not caused primarily by the fact that employers cannot find the skills they want because millions of Americans have acquired to the wrong skills due to the above misallocation.”

They will be re-allocated to other jobs. Initially they offer low productivty and I would suggest their remuneration in a new industry will reflect this.

I like the idea of a jobs guarantee instilling and maintaining certrain skills via an employment buffer, and I am a big believer of a high minimum wage. I also feel NAIRU is an undisclosed class-war by the rich against the working classes, but have successfully managed to suprress dissent to date, and character assassinating opponents with catch cries of “politics of envy”, so please do not get the impression I am a neo-classical.

My view so far is that MMT by itself is not ideological based, it’s a normative observation of a fiat money economy. it obviously has scope to be interpreted afterwards by ones ideological leanings.

I however would like to know how, under Bill’s ideological leanings, a reversal of a misallocation of resources occurs when a policy response is to maintain previous levels of aggregate demand.

I apologise to Bill in advance of my interpretation is incorrect.

fyi

Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy:

Does the Money Multiplier Exist?

http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/201041/201041pap.pdf

“some academic research and many textbooks continue to use the money multiplier concept in discussions of money….” (because they are insane perhaps)

“We………………document that the mechanism does not work through the standard multiplier model or the bank lending channel. In particular, if the level of reserve balances is expected to have an impact on the economy, it seems unlikely that a standard multiplier story will explain the effect.”

“Second, there is no direct link between money-defined as M2-and bank lending.”

“Changes in reserves are unrelated to changes in lending, and open market operations do not have a direct impact on lending. We conclude that the textbook treatment of money in the transmission mechanism can be rejected. Specifically, our results indicate that bank loan supply does not respond to changes in monetary policy through a bank lending channel, no matter how we group the banks.”

MMT is new to me. I was wondering whether there are any unique insights from the theory relating to how large foreign trading partners would react to increased deficit spending or how exchange rates might be impacted and what the consequences of such reactions or impact would be on the national welfare.

Specifically, how would MMT policy prescriptions impact foreign currency reserves held by china, japan, saudi. And how would MMT policy prescriptions impact the ability of Americans to afford foreign imports such as oil, electronics,..

Great blog by the way!

Hard to beleive that someone could think that by paying down a debt you can stimulate expenditure.

On the other hand if Country USA stimulates consumption and this causes export demand in Country China is it not China that is the major benificary? Eventually China is so stimulated it has an inflation problem? The end result is a stronger China. I dont see this as wrong just interesting, if the result is improved living standards in poor countries it a good result for the world but a downer for the populations that are borrowing to stimulate someone elses Country.

Billy – granted that China did a pretty good job with the direct stimulus, as opposed to US banker bailout variety, there are plenty of of data about to seriously question the misallocation of funds and capital. i.e: the 64.5 million urban electricity meters registered zero consumption over a recent six-month period, the purpose built but empty cities and shopping malls. The stimulus might have saved China today but what happens tomorrow?

Dave L, Ken and Ralph: Some peeps see similarity between the Austrian Business Cycle Theory and Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis. I think they both recognize that the private sector can get overleveraged, and in another commenter’s words, poop itself. This puts both of them way ahead of mainstream astrology^H^H^H^H^H^H / economics. Regarding Krugman’s old piece, as I commented on Krugman’s blog, phlogiston theory is true – phlogiston is just “valence electrons”. The Austrian recommendation for a hangover, caused by too much bank credit = alcohol is “never drink anything again ever.” The MMT/ Keynesian recommendation is – drink lots of water = deficit-spent high powered money. In the real world, much of the problems of a hangover is simple dehydration.

@ Some Guy. Almost perfect. However, I would expand The Austrian recommendation for a hangover, caused by too much bank credit = alcohol is “never drink anything again ever” to, A hangover is good for you. Go cold turkey (liquidation) and the result will cure you of ever wanting to drink (use credit or allow “unsound money”) ever again.

Of course, we know that “remedy” never works for long. In fact, it usually fades by 5PM cocktails. 🙂

You are correct, it’s mostly dehydration (demand-drain). Nice analogy.