I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The old line back to free market ideology still intact

The US economy is showing signs of slowing as the fiscal stimulus is withdrawn and the spending contractions of the state and local government increasingly undermine the injections from the federal sphere. The recent US National Accounts demonstrate that things are looking very gloomy there at present. In the last week some notable former and current policy makers have come out in favour of austerity though. Some of these notables contributed to the problem in the first place through their criminal neglect of the economy. Others remain in positions of power and help design the policy response. A common thread can be found in their positions though. A blind faith in the market which links them intellectually to the erroneous views espoused by Milton Friedman. His influence remains a dominant presence in the policy debate. That is nothing short of a tragedy.

Facts

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis released the June quarter National Accounts data for the US on Friday, July 30, 2010, which showed that:

Real gross domestic product — the output of goods and services produced by labor and property located in the United States — increased at an annual rate of 2.4 percent in the second quarter of 2010, (that is, from the first quarter to the second quarter), according to the “advance” estimate released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the first quarter, real GDP increased 3.7 percent.

While, the June release is subject to revision in late August, the results are signalling that the US economy is now slowing down as the fiscal stimulus is withdrawn.

The press clearly saw it that way.

The UK Guardian said on July 30, 2010 that US economy shows signs of slowdown as consumer spending falters. They amplified this headline with the following:

The US recovery appears to be faltering after a slowdown in consumer spending dampened growth and fuelled fears of a double dip recession … Slower growth across the US, where almost one in 10 are out of work, was expected by economists. But many expressed surprise at the extent of the slowdown and the continued anxiety among consumers. While business investment grew strongly, consumers sat on their hands. Spending on services was especially weak with figures showing a meagre 0.8% annual rise.

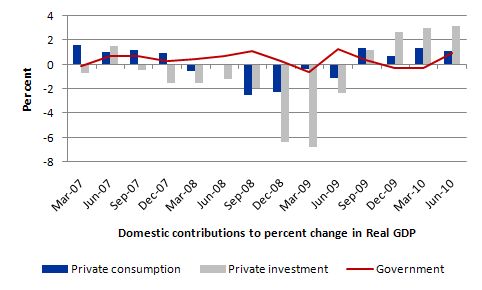

The following graph focuses on what is happening with the components of real GDP growth. It shows the percentage contributions of the main aggregate demand components from the first quarter 2008 to the June 2010 quarter.

A major problem for the US government now is that the stimulus at the federal level is being increasingly undermined by the the cuts occuring in public spending at the state and local government levels. The US federal system is working against itself. Further while private investment has been growing modestly, private consumption has tapered off again.

The BEA say that:

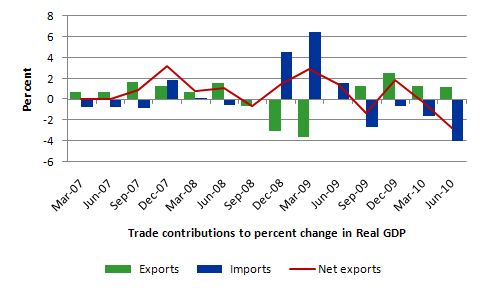

The deceleration in real GDP in the second quarter primarily reflected an acceleration in imports and a deceleration in private inventory investment …

The next graph shows the percentage contributions to the percent change in Real GDP from the first quarter 2007 to the June 2010 quarter arising from the trade sector. While exports have grown modestly (slowing in the June quarter though), imports have accelerated and drained 4 per cent from the real GDP growth in the June quarter.

Fiction

Former US Federal Reserve boss, Alan Greenspan was interviewed on Meet the Press yesterday (August 1, 2010). David Gregory was the MSNBC chair.

Greenspan appeared along with the mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg; and governor of Pennsylvania, Ed Rendell.

Gregory asked Greenspan whether the US economy would get worse before it gets better. If you can work out the double-talk answer then you get a bonus point. This is what Greenspan said:

Maybe, but not necessarily. I think we’re in a pause in a recovery, a modest recovery. But a pause in the modest recovery feels like quasi recession.

He went onto explain how the top-end-of-town had received the benefits of the stimulus and that if there is a further fall in house prices then the economy might double dip back into recession.

He was asked where unemployment would be through 2010 and beyond. He replied:

I feel we just stay where we are. The–there is a gradual increase in unemployment, but not enough to reduce the level of unemployment … I would say that there’s nothing out there that I can see which will alter the, the, the trend or the level of unemployment in this context.

So nothing at all to say about this other than it won’t get better.

He was then asked about the need for interest rates to rise again. He said:

Well, the problem there implies that the government has control over those rates, meaning the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department, in a sense. There is no doubt that the federal funds rate, that is the rate produced by the Federal Reserve, can be fixed at whatever the Fed wants it to be, but which the government has no control over is long-term interest rates, and long-term interest rates are what make the economy move. And if this budget problem eventually merges to the point where it begins to become very toxic, it will be reflected in rising long-term interest rates, rising mortgage rates, lower housing. At the moment, there is no sign of that, basically because the financial system is broke and you cannot have inflation if financial system is not working.

Greenspan knows full well, as does his successor Bernanke, that the central bank in tandem with the US Treasury could control investment rates if they wanted to. Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

But his reply also is an examples of one of those “well crowding out is a bad problem, but empirically there is no sign of it, but it is only a matter of time.” This sort of response is commonplace as the ideologues who just quote from mainstream macroeconomics textbooks cannot face the fact that their understanding of how the economy operates is false and the data is showing that.

The empirical world is being very harsh to the goldies, the Austrians and the neo-liberals at the moment. But rather than take a robust intellectual position and admit they got it wrong entirely, their ideological minds have to say – well it will get bad eventually. It might and it might not. But whatever happens – it won’t validate their erroneous theoretical conceptions.

Greenspan was then asked whether extending the tax cuts that are due to expire at the end of 2010 would be the solution. Greenspan had previously told a finance journalist in an interview that the Government “should follow the law and then let them lapse.”

The previous interview has then posed the problem that allowing the tax cuts to vanish would depress growth. Greenspan had answered: “Yes, it probably will, but I think we have no choice in doing that, because we have to recognize there are no solutions which are optimum. These are choices between bad and worse.”

So “Meet the Press” asked him to clarify the statements made in the earlier interview:

MR. GREGORY: You’re saying let them all go, let them all lapse?

MR. GREENSPAN: Look, I’m very much in favor of tax cuts, but not with borrowed money. And the problem that we’ve gotten into in recent years is spending programs with borrowed money, tax cuts with borrowed money, and at the end of the day, that proves disastrous. And my view is I don’t think we can play subtle policy here on it.

The problem that the US economy has gotten into in recent years are the legacy of the blind faith in the market that Greenspan promoted vigorously during his term in office. This led to a massive grab of real GDP by the financial sector which then gambled it to advance their own greed.

The gamble failed and the real economy collapsed as private spending faltered. The only thing that saved us from another depression was the fiscal interventions with some monetary policy support.

The fact that governments are borrowing when they are sovereign in their own currencies reflects the dominance of the neo-liberal paradigm. It is voluntary and basically financially harmless but totally unnecessary. The political damage it is causing though is the problem.

Recall the Time article (which covered the Russian and Latin American debt crisis) as I watched the US PBS Frontline program The Warning which went to air in the US on October 20, 2009. It is available via the Internet now and is worth viewing if you have the time. It documents that struggles that Brooksley Born, who became the head of the US federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission had with the Committee that Saved the World.

I especially liked the segment which described Born’s first lunch with Greenspan after she was appointed as Head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Apparently, Greenspan expressed a “disdain for regulation” and when she raised the issue of the problem of financial fraud Greenspan said that “the market would take care of the fraudsters by self-regulating itself”.

So never mind the real damage caused to people’s life savings or life-time employment entitlements (pensions etc) or jobs – the market will see to it that a monumental failure driven by fraud (for example, Enron) is sorted out. And … meanwhile … very few of the fraudsters ever really get rounded up and punished.

Born had wanted to regulate the growing and secretive Over the Counter (OTC) derivatives market and met with great resistance from Rubin, Greenspan and Summers. She told the program that “Alan Greenspan at one point in the late ’90s said that the most important development in the financial markets in the ’90s was the development of over-the-counter derivatives”.

When asked if Greenspan knew what he was talking about, Born replied “Well, he has said recently that there was a flaw in his understanding”. The last comment is in relation to testimony that Greenspan gave to the US Congress in October 2008 which I discuss below.

Born got involved in the law suit filed by filed by Procter & Gamble against Bankers Trust. It is clear that BT were screwing Procter by selling them derivatives that were too complicated for them to understand the risk. The program reveals audio-tapes of Bankers Trust brokers talking about their deliberate “intention to fleece the company” (Procter). One said “This is a wet dream” while there was a lot of laughing about how smart BT was in “setting up” Procter as a pigeon (victim).

At that stage Born saw the need for government regulation of the financial sector (particularly the banks) but she met incredible resistance from the Adminstration and Greenspan.

But Born’s efforts to seek ways of regulating the OTC market didn’t stop the awesome trio – The Committee to Save the World. She sought to develop a “concept release” – a plan for regulation within the legal jurisdiction of the CFTC.

The Committee to Save the World with another came out publicly on May 7, 1998 which this Press Release from Rubin, Greenspan and Levitt (SEC Chair) issued by the US Treasury:

JOINT STATEMENT BY TREASURY SECRETARY ROBERT E. RUBIN, FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD CHAIRMAN ALAN GREENSPAN AND SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION CHAIRMAN ARTHUR LEVITT

On May 7, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) issued a concept release on over-the-counter derivatives. We have grave concerns about this action and its possible consequences. The OTC derivatives market is a large and important global market. We seriously question the scope of the CFTC’s jurisdiction in this area, and we are very concerned about reports that the CFTC’s action may increase the legal uncertainty concerning certain types of OTC derivatives.

The concept release raises important public policy issues that should be dealt with by the entire regulatory community working with Congress, and we are prepared to pursue, as appropriate, legislation that would provide greater certainty concerning the legal status of OTC derivatives.

This New York Times article from last year – Taking Hard New Look at a Greenspan Legacy provides a good summary of the events. It documents the fierce opposition that Greenspan, Rubin and Summers put up against any notion of regulation of the financial markets.

So now Greenspan is advocating fiscal austerity when he knows it worsen the economy and knows that unemployment will also rise.

He knows full well that public debt is unproblematic and is not akin to private debt. He knows that when there is such a huge reservoir of excess capacity in the US economy that extra spending is required and that the debt-repayments provides income to the private sector.

But his public comments would suggest he is stupid in relation to presenting an accurate portrayal of how the modern monetary system operates. But we know he is not stupid – he understands the opportunities the government has. So he is just choosing to deliberately mislead the public and advance his extremist ideological agenda.

He is nothing more than ideological warrior who is prepared to distort public perception. That should come as no surprise given that the extremist Ayn Rand was Greenspan’s intellectual light.

Please read my blog – Being shamed and disgraced is not enough – for more discussion on this point.

More fiction

On Thursday July 29, 2010 the CEO of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, Richard W. Fisher gave a speech entitled – Random Refereeing: How Uncertainty Hinders Economic Growth – to the Greater San Antonio Chamber of Commerce. So a forum stacked with business types.

His speech continued to air the view that is now commonplace in the public debate that government policy is now making the recession worse and things would be better if the government just set some rules and let the market rip.

He said:

I have ascribed the economy’s slow growth pathology to what I call “random refereeing” – the current predilection of government to rewrite the rules in the middle of the game of recovery. Businesses and consumers are being confronted with so many potential changes in the taxes and regulations that govern their behavior that they are uncertain about how to proceed downfield. Awaiting clearer signals from the referees that are the nation’s fiscal authorities and regulators, they have gone into a defensive crouch.

Of-course, much of the “uncertainty” is being driven by the fact that the government stimulus is now being withdrawn and austerity programs which are cutting peoples’ incomes and pensions are now being pursued with vigour.

Fisher doesn’t mention that.

He claims that the government should set rules and stick to them.

I would not defend the performance of the US Government or the US members of congress. From a distance they seem to have little regard for the crisis they are overseeing.

Fisher claims that the current fiscal situation is crowding out private spending, making it impossible for the US government to deal with the recession (because they have run out of money) and hindering the capacity of “individuals to smooth their consumption over the business cycle” and raising the “probability of a debt crisis”.

So you realise that he is another free market ideologue who chooses to mimic the erroneous mainstream macroeconomics textbook mantras.

Underpinning of the crowding out hypothesis is the old Classical theory of loanable funds, which is an aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

Mainstream textbook writers (for example, Mankiw) assume that it is reasonable to represent the financial system to his students as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consequences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

The erroneous mainstream logic claims that investment falls when the government borrows to match its budget deficit – the borrowing allegedly increases competition for scarce private savings pushes up interest rates. The higher cost of funds crowds thus crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. This leads to the conclusion that given investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

But the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes (real) interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

Further, from a macroeconomic flow of funds perspective, the funds (net financial assets in the form of reserves) that are the source of the capacity to purchase the public debt in the first place come from net government spending. Its what astute financial market players call “a wash”. The funds used to buy the government bonds come from the government!

There is also no finite pool of saving that is competed for. Loans create deposits so any credit-worthy customer can typically get funds. Reserves to support these loans are added later – that is, loans are never constrained in an aggregate sense by a “lack of reserves”. The funds to buy government bonds come from government spending! There is just an exchange of bank reserves for bonds – no net change in financial assets involved. Saving grows with income.

But importantly, deficit spending generates income growth which generates higher saving. It is this way that MMT shows that deficit spending supports or “finances” private saving not the other way around.

Acknowledging the point that increased aggregate demand, in general, generates income and saving, Luigi Passinetti the famous Italian economist had a wonderful sentence I remember from my graduate school days – “investment brings forth its own savings” – which was the basic insight of Keynes and Kalecki – and the insight that knocked out classical loanable funds theory upon which the neo-liberal crowding out theory was originally conceived.

Further, there is a zero probability that the US government will face a solvency crisis with respect to its debt issuance. There is not increasing probability of a debt crisis.

Finally, the consumer smoothing argument is based on the Ricardian Equivalence nonsense that I have blogged about regularly. Please read my recent blog – Defunct but still dominant and dangerous – for more discussion on this point.

Fisher then invoked the inflation myth:

Let me close this discussion of fiscal uncertainty with one more thought. Some of you may wonder whether our elected officials, faced with the truly monumental task of balancing the nation’s books, might simply throw in the towel and turn to the Fed to print us out of this enormous fiscal hole. If such a request were ever made, there should be no uncertainty: We at the Fed cannot and will not monetize the debt. We know what happens when central banks give in to those requests – it leads us down the slippery slope of debasing our currency and puts us on the path of hyperinflation and economic destruction. Neither I nor my colleagues are willing to risk that legacy.

Please read the following blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks for further discussion as to why this is sheer nonsense.

The root source of the fiction

It all reminded me of a 1973 Playboy interview with Milton Friedman, which was one of the only times that I can recall (and I was young at the time) that the sycophantic press really homed in on the ideologue from Chicago.

At one point in the interchange Friedman was asked to explain how the Federal Reserve System causes inflation. He replied:

… The Fed, because it’s the government’s bank, has the power to create – to print – money, and it’s too much money that causes inflation. For a rudimentary understanding of how the Federal Reserve System causes inflation, it’s necessary to know what it has the power to do. It can print paper money; almost all the bills you have in your pocket are Federal reserve notes. It can create deposits that can be held by commercial banks, which is equivalent to printing notes. It can extend credit to banks. It can set the reserve requirements of its member banks – that is, how much a bank must hold in cash or on deposit with the Federal Reserve Bank for every dollar of deposits. The higher the reserve requirement, the less the bank can lend, and conversely.

These powers enable the Fed to determine how much money-currency plus deposits – there is in the country and to increase or decrease that amount.

So I would fail the now deceased Chicago professor if he submitted this to me as an answer. I would fail it because it doesn’t reflect the way the monetary system functions nor the way the central bank interacts with the commercial banks.

This is the mainstream macroeconomics text book view that you will still see in books like Mankiw. In his Principles of Economics (I have the first edition), Mankiw’s Chapter 27 is about “the monetary system”. In the latest edition it is Chapter 29.

In the section of the Federal Reserve (the US central bank), Mankiw claims it has “two related jobs”. The second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

In the blog – Money multiplier – missing feared dead – I explain how the money supply is endogenous (that is, the central bank cannot control it) and depends on the credit-seeking behaviour of the private sector and the commercial banks’ responses to this behaviour.

The idea that some money multiplier exists that scales up the central bank creation of the monetary base is totally false. There is in fact no unique relationship of the sort characterised by the erroneous money multiplier model in mainstream economics textbooks between bank reserves and the “stock of money”.

See also the September 2008 edition of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy – where they explain that the central bank targets the short-term interest rate as an expression of monetary policy and cannot control the money supply.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

It is a myth that the reserve requirements constrain the bank’s capacity to lend. They just mean that the central bank has to ensure there are at least that volume of the reserves in the system. They might try to supply those reserves at a prohibitive rate but then they will compromise their target policy rate.

Please read my blog – Money multiplier – missing feared dead – for more discussion on this point.

I will write more about Friedman’s errors in another blog later this week sometime.

Playboy continued to probe this issue and Friedman said that the Federal Reserve system was vulnerable because:

it’s a system of men and not of rules, and men are fallible … we can take some of the discretionary power away from the Fed and make it into a system that operates according to rules. If we’re going to have economic growth without inflation, the stock of money should increase at a steady rate of about four percent per year – roughly matching the growth in goods and services. The Fed should be required to take the kind of limited action that would ensure this sort of monetary expansion.

So once again there is an erroneous claim that central banks could control the money supply. This belief led to the embarrassing period of monetary targetting which was the flavour of the decade from the mid-1970s. Friedman’s ideas were very influential in this period.

Central bankers were conned into believing that by controlling the money supply they would control inflation. Milton Friedman told the profession that if the central bank reduced the growth rate of the money supply to the potential rate of real output growth then the inflation rate would stabilise at zero.

So if you desired a 1 per cent inflation rate and your “fully employed” economy could generate real GDP growth at 4 per cent, then the nominal growth in the money supply should be set at 5 per cent. This was the basis of monetary targetting.

My own stupid nation was one of the first to implement this stupidity in March 1976 just after the conservatives “stole” the federal government with the help of the CIA (see Australian constitutional crisis for more on that).

In Australia, as elsewhere, the policy was a total failure. There was no clear relationship anyway between the measured growth in the broad monetary aggregates (the money supply) and the rate of inflation.

Further, the between August 1978 and the time the conservatives were thrown out of office in March 1983, actual monetary growth exceeded the targets. And … both inflation and high unemployment remained at high levels.

Interestingly, the Labor party (the so-called political arm of the trade union movement) which swept to office in 1983 continued with the policy. This was the early warning sign that the progressive party in Australian politics had sold out to the neo-liberal agenda. It got worse from then on. Unfortunately, we are still caught in that mindset.

At the time though, the “markets” – which are still seen as the oracles of good policy – were strongly behind targetting despite its total failure. The Labor party scared they would put the “bond traders” off-side, retained the policy.

By the mid-1980s it was clear the policy approach was a total crock. The central bank could not control the money supply. The stupidity was abandoned in Australia in January 1985.

It demonstrated that the mainstream macroeconomics text book models were (and remain) useless for understanding how the monetary system operates.

Yet these modern day monetary commentators still appeal to the same starting points and hold out Friedman as if he has anything to offer us. He had nothing to offer when he was alive and in his “prime”. He has nothing to offer us now as a legacy of his work.

All I remember him for is the damage he did in Chile after the democratically-elected Allende government was overthrown by a brutal military dictatorship with the support of the US government. Please see the film – The Battle of Chile – for more information on this.

Now, back to the Playboy interview. Friedman was then asked if the central bank was forced to set monetary policy by rules “wouldn’t the Fed lose its emergency powers – powers that would be useful in a crisis?”. Friedman said:

Most so-called crises will correct themselves if left alone. History suggests that the real problem is to keep the Fed, operating on the wrong premises, from doing precisely the wrong thing, from pouring gas on a fire. One reason we’ve so many government programs is that people are afraid to leave things alone when that is the best course of action. There is a notion – what I’ve called the Devil Theory – that’s often behind a lot of this …

PLAYBOY: But you prefer the laissez-faire – free-enterprise – approach.

FRIEDMAN: Generally. Because I think the government solution to a problem is usually as bad as the problem and very often makes the problem worse …

So we are just getting a reprise of this basic view.

Friedman was asked at one point (not in this interview) how long it would take for unemployment to fall back to its so-called (mythical) natural rate after rising to kill off inflation. He said about 15 years. So 10 or more percent unemployment for 15 years … and that is if his model of self-correction works.

The modern proponents of the “government makes things worse” lobby won’t even put a figure on what would have happened if the stimulus packages were not introduced nor will they tell us how long it would take before trend growth is resumed and whether the trend remained undamaged (via the hysteresis).

My advice: any comments this lot make in the public debate should be instantly disregarded.

An aside – self-promotion and more fiction

It is not only the mainstream economists who have a crying need to pursue celebrity at the expense of compromising themselves with lies and misrepresentations. Even so-called progressives do it.

In a recent Interview in the Australian media, Steve Keen was quoted as saying:

I’m not a fan of what’s called Chartalist economics that argues the government can run any size deficit it likes … I believe there are limits there, but nonetheless if you have private sector deleveraging, then the last thing you want to have there is the government doing exactly the same thing – it will just take cash flow out of the economy and push it down.

When have any MMT economists said that there are no limits on the size of the public deficit? Answer: Never.

When have MMT economists said that the government can run any size deficit it likes? Answer: Never.

The statement that a sovereign government is not financially constrained is not equivalent to either of the previous statements.

Associate Professor Steve Keen (an academic ranking which is below full professor in the Australian system) – clearly doesn’t understand what Modern Monetary Theory is about despite continually making public statements criticising it.

Or, perhaps, he chooses to deliberately misrepresent it because he realises his own forecasts of what was going to happen as the crisis unfolded have been found to be badly wanting and he knows that MMT is the only theoretical position left standing at present that has any credibility.

But then if you cannot get simple accounting correct I suppose there is not much to expect beyond that.

Conclusion

It is clear that reinvention and historical revisionism is the order of the day. More and more of these neo-liberal zealots are speaking out again – after being initially shamed and silent.

The irony is that fiscal policy has reduced the damages their actions (or inaction) caused yet they are doing their best to undermine it. Given their links to the top-end-of-town which has clearly profited massively from the public handouts, it is no surprise that they want to stop the fiscal expansion in its tracks for fear that some of the largesse might be spread a little further to the unemployed.

It is a pity the ordinary Americans couldn’t see it within their powers to redux their revolution when they threw the British (and French and Spanish) out. This time their targets should be Wall Street and all its connections in the political sphere.

Some people have just stopped earning the chance to be listened to any longer.

That is enough for today!

I happened to watch a segment on CNBC with the St. Louis Fed President James Bullard. As a traditional inflation hawk, he caused a lot of commotion by coming out and warning about the risks of deflation in the near future. In the TV segment, he made the argument that the Fed’s “extended period” language might actually prove counterproductive. Although he said the most likely scenario is a modest recovery, he mentioned that an external shock — like the Euro debt crisis for example — might serve to push inflation expectations lower and cause inflation. The conservative, pro-business host of the program asked Bullard if he thought that the confusion and uncertainty over recent government legislation such as health care reform is serving to depress business confidence. Without expressing outright approval, Bullard offered his support for the host’s contention.

All throughout the conversation with the regional Fed president, there was plenty use of the words “inflation expectations”, “shocks”, “business uncertainty”, etc., but not once was the word “demand” uttered. There was talk about unemployment, but only in the context of price stability — to the Fed president, the problem with high unemployment is not in the human suffering or lost real output, but rather in the fact that it keeps “inflation expectations” too low for his liking!

A common retort I hear from fiscal conservatives is that government stimulus is an illusory “free lunch” proposal — i.e. there is no such thing as a magic cure. Economists subtly argue this when they use terms such as “inflation expectations” and “shocks”, terms which emphasize their belief that recessions and unemployment are “real” phenomena and not demand-driven. But here on the business channel we have a regional Fed president and a panel of hosts and reporters seriously considering whether or not the Fed should change the language in their FOMC minutes! Who cares?!?! These same conservatives who chide fiscal stimulus as “too easy” are suggesting that a change in the wording of a Fed press release might avert deflation! How fantastical is that?!?

Thank you for the graduate level education in what has been going on in the halls of high finance over the course of the past 10 years, bringing about the collapse of western civilization as we know it, but having it’s roots, no doubt, in the likes of Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist. It’s astounding that less than 60 years after the end of the civil war, and the consolidation of power in the US Government, that the world slid into a global depression, and here we are 70 years after the war to end all wars having slid into a second global depression.

If I understand the article’s conclusion correctly, then the sovereign debt of the US is insignificant compared to the consequences without increased federal spending. Even so, there’s a tipping point at which public sector spending crowds out private spending. And, to whom does the benefit of all of this spending accrue? I would prefer to teach a man to fish so that he might have to provide for himself and his family, than to dole out unemployment benefits. Has the pendulum swung so far in preserving the financial institutions which caused the collapse, along with the complicity of the federal government, that equilibrium with the private sector cannot be re-attained?

The important thing, I think, is to reduce federal spending and reduce taxes to return the American economy back to the private sector. Aside from the Fed and Treasury’s unfailing errancy and inability to acknowledge the failure of their collective world view, our federal government is still operating in a vacuum of denial. They figure as long as they can print and spend, the barbarian hordes will be kept at bay. The defense of the dollars they count on to fund their own retirement is their only motivation, which makes peculiar bedfellows of politicians and financiers. In the meantime, state governments are struggling to balance their budgets. with 11 states meeting the definition of bankrupt, and federal deficit spending continues it’s upward trajectory. This imbalance and lack of parity between Washington and the rest of the country could very well lead to a second American Revolution. The economy can not be centrally managed, this has been proven time and again. The longer the delay in returning the economy to the people, by cutting spending and taxes, i.e. shrink the federal government by any means necessary, the longer it will be before a recovery begins, and the more severe will be the consequences.

Dear Bill,

please take good care of your health so you would live longer, we, the sane citizens of this world, still need your guidance and hope you would see the transformation of ECONOMIC Studies in your life time . . .

Cheers

Anas

Bill,

when are we going to see some commentary from you in regard to economic policy in the current election debate. Major parties are both keen to talk about paying the debt down as soon as possible. No doubt Libs are much worse than Labour when it comes to stimulus and propping up the aggregate demand. When it comes to the only progressive party “Greens” I’m not convinced that even they really comprehend the MMT fully and the folly and myths of government debt, and least not publicly.

“Associate Professor Steve Keen (an academic ranking which is below full professor in the Australian system) – clearly doesn’t understand what Modern Monetary Theory is about”

Bill, what is it about? Where is the theory actually written down? I’ve read Mosler’s “Soft Currency Economics” which contains some fundamental flaws, which I have pointed out here: http://moslereconomics.com/2010/07/26/the-political-genius-of-supply-side-economics/ (comment 16 onwards) .

I asked you whether there is a definitive text or set of texts, in a comment on a recent post, but received no reply.

Bill,

Do you have the link to the Playboy article (or do you keep the magazines; for reference to the articles of course)? 🙂

Paul Andrews,

Understanding Modern Money – by Randall Wray is a good place to start. It’s a very simple book that anyone can understand. Well maybe not a neo-liberal, but most people shouldn’t have any trouble.

Most of what Wray’s book outlines is just common sense wehich unfortunately has never been the strong suite of neo-liberals.

Cheers.

Paul Andrews,

I believe some of the confusion arises because of different to MMT scholars theory of value you are using. So in your metrics government spending leading to additional employment may not create additional value if everything is “marked to market”. But this is not the point. We can always define such a metrics and exclude for example the implicit value of work provided by the Police officers who are employed by the State.

Yes we can always hire thugs on the free market to provide enforcement of our ideas. But this is rather the Zimbabwian model.

Haven’t said that I agree that under certain circumstances (in a degenerated command economy for example – I am sort-of familiar with that system) little of additional common-sense value is added when people are hired just for the sake of hiring.

Adam,

I am not referring to “mark to market”. Warren Mosler says in “Soft Currency Economics”:

“When people and physical capital are employed productively, government spending that shifts those resources to alternative use forces a trade-off. For example, if thousands of young men and women were conscripted into the armed forces the country would receive the benefit of a stronger military force. However, if the new soldiers had been home builders, the nation may suffer a shortage of new homes. This trade-off may reduce the general welfare of the nation if Americans place a greater value on new homes than additional military protection. If, however, the new military manpower comes not from home builders but from individuals who were unemployed, there is no trade-off. The real cost of conscripting home builders for military service is high; the real cost of employing the unemployed is negligible.”

My comment explains that there is a trade-off. It doesn’t matter how you value the resources consumed versus the resources produced, there is a trade-off. I’m not talking about dollar values as such. Subjectively we may disagree about the relative “value” of the costs and benefits, (e.g. in this case the benefit of having a stronger miltary versus the cost of supplying soldiers with resources both to do their job and to reward them for doing their job), but to deny there is a trade-off is a big mistake. And this is in the introduction of a supposedly seminal MMT work.

I will take a look at Wray’s book.

Bill,

You may wish to consider giving Reagan era budget director David Stockman a blast from the blog:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/01/opinion/01stockman.html?pagewanted=1&sq=david%20stockman&st=cse&scp=1

Bill,

Even if Neill above was correct (which I know he’s not), so long as everyone has a job (public or private) then we would live in a more civilised world.

As I understand it Neil’s reference to ‘needing to balance the budget’ is illogical. The government sector deficit balances the private sector surplus!

I echo Anas Alil’s words above. Make sure you get plenty of rest, as some us really care about you.

Kind Regards

Charlie

Paul Andrews,

I 100% agree that there is always a trade-off and only the simplified, introductory version of MMT presented on some blogs may contain statements creating an illusion that these trade-offs do not exist. Whenever I see “all things equal” an alarm bell rings in my head.

To me the key issue not discussed widely enough is the trade-off between increasing our current consumption of non-reneweable resources and leaving them for the future use or leaving them to allow the global ecosystem to function properly. Another aspect which is virtually missing tn the current discussion is the trade-off between increasing the quality of life in the Western countries by accepting cheap cargo from the developing countries and allowing for dismantling of the productive capacities combined with losing our skills. This is again a kind of intertemporal trade-off as in my opinion the West will pay a price for that.

On the other hand the Chinese and the others have every right to enjoy the same level of consumption we have.

The issue of price stability in the context of exchange rate gyrations may need to be addressed as well. But having to chose between 20% unemployment for 10 years and 20% CPI inflation for one year I would chose the cost-push inflation. Another trade-off.

Having said that I don’t see where these issues may invalidate MMT. This is just a monetary theory and I am asking questions which clearly transcende the limits of the monetary economics. However I would argue that clear understanding of the functioning of the financial system and the knowledge of the policy tools avaliable to the societies and governments is a precondition of addressing the problems I mentioned and these (private debt deflation) highlighted by Steve Keen as well.

This is what MMT should be about.

Paul:

Trade-offs exist in a zero-sum game. I would (in fact do) argue that both neo-liberals and conservatives describe the economy as a zero-sum game when it suits their interests. I don’t disagree that there are elements of our economic activity (environmental damage, resource scarcity, etc.), where a zero-sum context makes sense. But it is a mistake to characterize the entire economy as such.

The point Mosler was trying to make is that when employing the unemployed, the economic trade-offs don’t exist – the economy is as a whole better, you get more than what is input.

Yes, the work has to be meaningful, although just generating demand for someone else to fulfill is meaningful to the economy (so bankers CAN sleep at night knowing they are helping their fellow human beings) – but overall, work should generate something of material value.

The fact that someone has a cost of employment is not a trade-off if the value of the work exceeds that cost. Just because that value cannot be privately monetized doesn’t mean that value doesn’t exist.

Since the name of the Mother of Calamities and her beloved pupil has come up, I thought you might find this webcomic amusing: Ayn Rand’s Adventures In Wonderland: http://wonkette.com/415825/thats-objectivist-ayn-rand-in-the-21st-century

Terrific post as always Bill.

I’m sure you are well aware that Steve Keen is not the only economist to have misrepresented MMT as saying there is no limit to deficit spending. Paul Krugman did the same thing in his recent online debate with Jamie Galbraith here and here.

I think MMT makes very clear that deficit spending for a fiat-currency issuing government is limited by real resource and political constraints. Whenever deficit spending falls inside resource limits, the constraint is political. For academic economists to “misinterpret” this aspect of the theory – especially “Nobel Prize” winners – stretches credulity.

I recently discussed the exchange between Krugman and Galbraith here. I hope the shameless self-promotion can be forgiven. The post may clarify the limits to deficit spending for some who are relatively new to MMT.

“The government sector deficit balances the private sector surplus!”

I don’t think this is correct.

What about the following case?

I go and dig a tonne of gold out of my back yard, and sell it to Westpac, and “deposit the funds” in an account there (in other words, let them keep the gold on the promise that they will give me up to $46 million when needed):

Westpac: Assets: Tonne of gold; Liabilities: $46 million to Paul

Paul: Assets: $46 million; Liabilities: $0

Net private sector surplus: $46 million

Net public sector deficit: Zero

“Just because that value cannot be privately monetized doesn’t mean that value doesn’t exist.”

Of course – as mentioned above I am talking in terms of underlying costs and benefits, not in dollars. The government provides many services that have value, but which could never be “marked to market”.

There is no zero-sum game, as the productive elements of society are continually creating products, services and assets of value, from their brainpower and their labour. The assets are used as collateral, generating new loans and hence new funds.

Paul

Gold is no longer a financial asset – it is not a claim on anybody, it is a real asset. The private sector’s financial surplus in your example is still zero. Any bank can purchase a real asset by issuing deposit liabilities to the seller, but no net financial assets can be created this way.

Hence your example does not disprove the rule that “govt sector deficit balances private sector surplus”.

“Gold is no longer a financial asset – it is not a claim on anybody, it is a real asset. The private sector’s financial surplus in your example is still zero.”

So what the original premise more closely means for you is: “The government sector deficit balances the private sector financial surplus”

And you are defining financial to mean a claim on somebody.

So more closely again to the true meaning from your perspective: “The government sector deficit balances the increase in private sector assets that are claims on others, less the increase in private sector liabilities”.

I don’t think anyone can argue with that statement.

Where I think MMT goes astray is it takes the original unclarified statement and draws some conclusions about “money”, which is definitely not merely the difference between private sector assets that are claims and others, less private sector liabilities.

It uses a term “net money”, to mean the above, then claims to draw conclusions about “money” as if it was “net money”.

peterc,

In fact initially Krugman created a model with inflation-linked bonds which can breed like rabbits no matter what and there is no escape. But governments do not use TIPS to offset the deficit spending. They use ordinary bonds.

“In period 1, the government borrows, issuing indexed bonds (I could make them nominal, but then I’d need to introduce expectations about inflation, and we’ll end up in the same place.)…”

And here is the problem. Bonds yields do not have to be equal to inflation expectations and inflation expectations do not have to be accurate.

The second problem is obviously the P(t) = V*M(t) equation which may or rather may not be true.

Somebody who is more “knowledgeable in scripture” than me should clarify this issue with prof Krugman and he may accept certain provisions of MMT once he starts applying the rational expectations model only to some groups of people. (Bourgeois may have rational expectations. Workers and peasants have usually few)

However the issue mentioned in the second post is more interesting.

“Someday the private sector will see enough opportunities to want to invest its savings in plant and equipment, not leave them sitting idle, and the economy will return to more or less full employment without needing deficit spending to keep it there. At that point, money that the government prints won’t just sit there, it will feed inflation, and the government will indeed need to persuade the private sector to make resources available for government use.”

Again it looks that the quantity of money or quasi-money may matter. I believe that Paul Krugman may have heard a family story about the hyperinflation in Poland as his grandparents left the city called Brest-Litovsk (Brzesc Litewski) in 1922

SOURCE_http://www.genealogywise.com/profiles/blogs/in-search-of-a-man-selling

So he must have heard the same stories I heard when I was a kid (about bringing wages in a briefcase). My family lived not far away…

Based on that I don’t quite understand where he got his rational expectations from but let’s leave this topic for now.

So the problem which I can see is when the investors / savers discover that real interest rates are below zero they may try to dump the assets denominated in that currency thus pushing down the exchange rate even more. Does it depend on the quantity of financial assets denominated in that currency? I think so. Then the process of running away from the currency accelerates on its own. The interesting question is why the fiscal policy of imposing a land tax helped to halt inflation in Poland in 1923. Aristocrats and rich people didn’t contribute much to the aggregate demand. I believe the transmission channel was actually the exchange rate of the foreign currencies. Rich people were immediately changing Polish Marks into whatever hard currency they get. This was depressing the exchange rate and feeding back into the prices of imported goods.

What I remember from the hyperinflation period in 1989 was that people receiving wages who wanted to save were going straight to money exchanges with PLZ (old Zlote) to get either DEM or USD. Any “serious” transactions like buying an apartment were performed in USD. So the local currency was not performing and the rate of saving in PLZ was pretty much zero. Almost like in Zimbabwe…

Did the aggregate demand exceed the productive capacities? Of course. But this is also the point Paul Krugman is trying to make. If we have a stock of financial assets equal to 10000% of the GDP the system may easily lose its dynamic stability.

I have no time to research this. One day I may dig out the old Polish statistics from 1921-23 or 1988-91 and analyse them. For now let’s not discard what our old neighbour Krugman said, he may have a point…

One more thing. I disagree with branding people who do not understand or don’t 100% agree with the MMT. They may not have bad intentions and this may be unfair. I have no bad intentions and I accept that I may be an ignorant as I had only one semester of Marxist / neoclassical Economics 101 at the Uni. But arguments ad hominem won’t convince anyone…

Further to the above regarding “The government sector deficit balances the private sector surplus”.

Here is an example of it being used to draw a misleading conclusion: (from http://www.creditwritedowns.com/2010/05/mmt-economics-101-on-federal-budget-deficits.html )

“When the government sector runs a deficit, the non-government sector runs a surplus of equivalent size. Draw your own conclusions about what this means in an era of government fiscal austerity.”

No conclusion can be drawn, because of the limited underlying definition of surplus. If the government ran a surplus, the private sector could well have a very healthy surplus in terms of real assets.

Adam (ak): Krugman (like Keen) claimed that MMT says deficit spending can never be a problem. MMT does not say this. Krugman’s (and Keen’s) characterisation of the theory is a misrepresentation. I do think it strains credulity that they could fail to realise this. If they did fail to realise it, it could only be because they didn’t actually take time to check the viewpoint that they were misrepresenting. Krugman, in particular, is at the top of his profession, so to me innocent misinterpretation seems unlikely. In either case, both Krugman and Keen have created a strawman, which is usually done in a dishonest attempt to discredit a point of view. Whether they would agree with MMT, correctly interpreted, is a separate issue, and not the point of my comment.

peterc,

In my opinion even very smart people simply don’t like getting to the bottom of these issues because this would invalidate the theory they invested so much into. But this is not dishonesty. This may be a kind of intellectual failure. We are all humans. I am probably the last person who should lecture about that because my personal style is to pour acid first and then to watch what happens. I do it often and then I regret it later. So please believe me personal attacks will not help anybody. Engaging in discussions whenever possible and pinning down opponents with strong arguments will do the trick I believe.

I see the fear first, understanding later if ever is back in fashion.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/columnists/charlesmoore/7921664/A-timely-recounting-of-the-Weimar-disaster-that-aided-Hitlers-rise-to-power.html

Paul Andrews, August 2, 23:02.

Your comment # 17 on Warren Mosler’s blog assumes full employment. If there is full employment then diverting a worker from one task to another involves a trade-off. If the worker is unemployed there is no trade-off in terms of that worker’s labour. Warren Mosler assumes there is not full employment hence there is no trade-off.

Sorry Paul Andrews,

I can’t give you a textbook understanding of MMT but FWIW this is my intuitive understanding and so what follows could well be a misrepresentation. I would appreciate any feedback about where I have misunderstood MMT from the more knowledgeable posters.

Basically whatever you dig out of your backyard, be it gold or potatoes, can only obtain monetary value if someone is willing to exchange that produce for a financial asset. Unless you are in a ‘beads for Manhattan’ situation that financial asset only has value through taxes or interest and ultimately private interest arrangements need taxing to avoid currency annihilation. Runaway inflation or deflation under such an arrangement can mean all bets are off with the exchange value of your financial or real assets.

You need someone who can pay you in the currency that you get taxed on to buy the goods and services that are others need to sell to you to pay their taxes. So why sell to foreigners if the only financial assets you want are to save the value of your productivity through paying taxes? It is only possible if they are happy to pay you in the financial asset that you are taxed on.

Admittedly currency pegs, currency trading and monetary union arrangements obscure and complicate this basic international transaction. However it is worth bearing in mind that the only ways your government and the private sector can both be in surplus in any monetary form is if foreign governments and/ or foreign private sectors want your money, goods or services.

In other words your gold, potatoes, whatever has to be exchanged to have monetary value in the currency that is most efficient and realisable to either where, who and what you are. Most of us have ties in that regard, which, to some extent, make monetary considerations irrelevant.

Yes it is possible to export and earn an income if your county’s private and government sector are not spending enough of your financial asset at home for you to market your product at home. To do so your country has to produce either financial assets that foreign nationals want to save or invest in or be producing real services and goods that they want to the point that they are willing to fund both the private and public sectors of your economy through buying your government’s currency.

Of course this breaks down when the productivity of a national economy becomes wildly out sync with the monetary value of currency. Inflation occurs when the productive value of an economy cannot be realised because the flow of monetary value (not its quantity) out strips the economy’s capacity for the production of real goods and services. But the converse is also true. The productive capacity of an economy cannot be realised when flow of monetary value in an economy is not sufficient to pay for the full value of real goods and services in the economy and deflation is triggered.

Adam (Ak)

My brief taste of neoliberal influence on academia in Australia during the 80’s in my non- economic social science degree put me off doing any postgraduate study, until recently. I can only admire both Stephen Keen and Bill Mitchell to have come through the discipline of economics and still have the capacity to refute the nonsense. That said I understand Prof Mitchell’s frustration with Prof Keen’s public account of MMT which ignores the fundamental point that deficits are limited by the productive capacity of an economy.

“No conclusion can be drawn, because of the limited underlying definition of surplus. If the government ran a surplus, the private sector could well have a very healthy surplus in terms of real assets.”

Ah ha, a conclusion can be drawn – in such a situation you would have a deflationary scenario – a “very healthy surplus of real assets” with a reduction in net private financial assets. Less net financial assets representing a “healthy” (let’s assume that to mean larger in size relative to some earlier period) net real production.

Straight-forward is not equivalent to limited.

Let me qualify that last conclusion with the possibility of a private credit expansion, which would delay any deflationary episode.

And this assumes net zero effects from the external sector.

Great post, thanks!

Keith Newman,

“Your comment # 17 on Warren Mosler’s blog assumes full employment.”

This is not correct. Here is the comment, which assumes a level of unemployment:

—————-

Warren,

In “Soft Currency Economics”, you state:

“When people and physical capital are employed productively, government spending that shifts those resources to alternative use forces a trade-off. For example, if thousands of young men and women were conscripted into the armed forces the country would receive the benefit of a stronger military force. However, if the new soldiers had been home builders, the nation may suffer a shortage of new homes. This trade-off may reduce the general welfare of the nation if Americans place a greater value on new homes than additional military protection. If, however, the new military manpower comes not from home builders but from individuals who were unemployed, there is no trade-off. The real cost of conscripting home builders for military service is high; the real cost of employing the unemployed is negligible.”

There is a trade-off. Assume the unemployed person is receiving unemployment benefits B. Assume the wage for a military position is W. Let the difference the two be D. D = W – B. This represents the extra purchasing power of the person after he joins the military. The person now has access to more resources than before, through the additional purchasing power D, which leaves less resources for everyone else.

There is a second trade-off, which is the cost of employment of the person – insurance, equipment, uniforms etc. These need to be supplied from the resources of the nation, leaving less for the people.

There is third trade-off. While the person is serving in the military, he has no incentive, or even opportunity, to do his own work. He has no opportunity to exhibit entrepeneurship. He has no opportunity to start a small business that will create resources. Therefore the resources of the nation are diminished further.

These are the trade-offs that should be considered when employing someone in a government position. Sometimes it will be worth it and other times not. But let’s not pretend there is no trade-off.

Adam,

Are you the AK that comments on Steve’s blog?

Thanks very much for putting together a summary of your understanding of what MMT is. I will have a closer look later and comment further.

pebird,

“Ah ha, a conclusion can be drawn – in such a situation you would have a deflationary scenario – a “very healthy surplus of real assets” with a reduction in net private financial assets. Less net financial assets representing a “healthy” (let’s assume that to mean larger in size relative to some earlier period) net real production.”

“Let me qualify that last conclusion with the possibility of a private credit expansion, which would delay any deflationary episode.”

In other words no conclusion can be drawn purely on the basis of there being a government sector surplus.

Further to this: “In other words no conclusion can be drawn purely on the basis of there being a government sector surplus.”

Not only is one not able to draw a conclusion as to whether there will be inflation or deflation, one is also not able to draw a conclusion as to whether there will be a surplus of real assets.

A government deficit can coexist with a surplus in real private sector assets.

A government deficit can coexist with a deficit in real private sector assets.

A government surplus can coexist with a surplus in real private sector assets.

A government surplus can coexist with a deficit in real private sector assets.

The fact is we have too many people either without work ,with not enough hours of work, or receiving a rate of pay that is insufficient to maintain any reasonable standard of living.

Rises in productivity have often seen profits increase and yet real wages have not followed suite.

The other common thread through all this is that government surpluses appear to have forced many people into using up all their savings to maintain a standard of living and then once the savings run out they seek credit to simply exist.

That’s not greed it’s a necessity in this day and age because those who are a little different or don’t keep up with trends are pretty much cast aside like lepers.

Hence, many people could care less about real private sector assets because they appear to be in the hands of a few and the majority are probably paying for them.

For Paul Andrews, August 4 at 8:30:

I didn’t express myself clearly. The full employment you are assuming is not full employment of labour but rather full employment of productive capacity. You write:

“There is a trade-off. Assume the unemployed person is receiving unemployment benefits B. Assume the wage for a military position is W. Let the difference the two be D. D = W – B. This represents the extra purchasing power of the person after he joins the military. The person now has access to more resources than before, through the additional purchasing power D, which leaves less resources for everyone else.”

My response: The person does indeed have access to more resources than before. But there can only be fewer resources for everyone else if all resources were previously fully employed. If there were idle resources available then the allocation of these resources to the now newly employed worker does not come at the expense of anyone else. No trade-off occurs in this case.

“There is a second trade-off, which is the cost of employment of the person – insurance, equipment, uniforms etc. These need to be supplied from the resources of the nation, leaving less for the people.”

My response: Same as above.

“There is third trade-off. While the person is serving in the military, he has no incentive, or even opportunity, to do his own work. He has no opportunity to exhibit entrepeneurship. He has no opportunity to start a small business that will create resources. Therefore the resources of the nation are diminished further.”

My response: I agree that excessive military expenditures are a lost opportunity for a country even if it is idle resources that are being deployed. If the person was hired to improve infrastructure or educate other people, etc, his/her work would increase the resources of the country.

Alan,

“The fact is we have too many people either without work ,with not enough hours of work, or receiving a rate of pay that is insufficient to maintain any reasonable standard of living.”

Agreed. The question is: Why? The answer is not necessarily to be found in the private sector surplus of claims on others.

“Rises in productivity have often seen profits increase and yet real wages have not followed suite.”

Agreed again. So why the MMT fixation on aggregate private surplus?

“The other common thread through all this is that government surpluses appear to have forced many people into using up all their savings to maintain a standard of living and then once the savings run out they seek credit to simply exist.”

Where is the evidence that government surpluses have forced people into using up all their savings? Who decreed that the standard of living to be maintained includes a large house, two new cars every three years, restaurant meals once or twice a week, huge flat screen TV, designer clothing etc. etc? People want to keep up with the Jones’s, and the availability of private credit has enabled a lifestyle arms race. This is nothing to do with whether the government has a surplus or a deficit, especially in times when private sector credit far exceeds public sector credit.

“That’s not greed it’s a necessity in this day and age because those who are a little different or don’t keep up with trends are pretty much cast aside like lepers.”

Bingo! It’s only a necessity for those who feel they must keep up with the Jones’s. Anyone else is “different”. This is a huge driving force in a consumerist society. It can’t go on forever though, because at some stage GDP will not support the debt-service on the total stock of credit. Hopefully our society will be a little more accepting of differences when the credit cycle passes its peak.

“Hence, many people could care less about real private sector assets because they appear to be in the hands of a few and the majority are probably paying for them.”

Nearly all the people I know seem to care a great deal about real private sector assets – especially houses and their contents! Unfortunately these people’s love of real private sector assets has blinded them to the real cost – i.e. the cost denominated in future labour hours. To the other people, the debt-free non-materialists, I say congratulations!

Keith,

Thanks for your thoughtful response.

“The person does indeed have access to more resources than before. But there can only be fewer resources for everyone else if all resources were previously fully employed. If there were idle resources available then the allocation of these resources to the now newly employed worker does not come at the expense of anyone else. No trade-off occurs in this case.”

There is some truth in this. However resources are not homogeneous, so there is still a trade-off. Assume the total resources available are R. Of these, some are idle and would be wasted if not needed by anyone. Call these Ri. Others are not idle, call these Ra. So R = Ri + Ra. The newly employed person will consume some of Ri and some of Ra – call this consumption Ca and Ci. I agree that the consumption of Ri is not a direct negative for the economy (although there may be indirect negative effects). However, the rest of the economy now has access to Ra – Ca, whereas previously it had access to Ra.

“I agree that excessive military expenditures are a lost opportunity for a country even if it is idle resources that are being deployed. If the person was hired to improve infrastructure or educate other people, etc, his/her work would increase the resources of the country.”

Yes, if the person is doing something that benefits the country, and those benefits exceed Ca + the debt service costs on the government borrowing, I agree. However I believe this becomes hard to achieve when the objective is purely to stimulate. It also becomes harder to achieve as the debt service costs increase. The objective should be to benefit the country through productive endeavours rather than to stimulate for stimulation’s sake.

@paul andrews

“Where is the evidence that government surpluses have forced people into using up all their savings?”

Now it is you who is confusing the difference between real and financial assets 🙂

“People’s Savings” are financial assets, namely a claim on someone else rather than a real asset like a tonne of gold. And, as you agreed in an earlier post on this very thread, it is obvious and uncontestable that if the government runs a surplus, that must be at the expense of private sector financial assets. They are two names for the same thing!

A financial asset is always a claim on someone else, and is consequently an exactly equal liability for someone else. That is what a ‘financial asset’ is, as opposed to a real asset.

Therefore, the sum total value of all the financial assets in the world is, always has been, and always will be, zero.

Anyone can create a financial asset, as long as they create the corresponding liability at the same time – it’s called writing an IOU. Banks do it when they issue loans, companies do it when they issue bonds. You can do it when you didn’t bring enough cash to a poker table.

Governments do it when they print money (or create bank reserves, same thing). Or, for that matter, when they issue debt, which is why the whole ‘printing money will be inflationary so we must borrow it instead’ line is so silly. A dollar bill is just one dollar loaned to the government at no interest.

The MMT insight is that, since the total value of financial assets is always zero, if the private sector wants to accumulate them (have a net non-zero amount), the government must, as a simple question of logic, be the ones with the corresponding liability. There aren’t any other players at the table! (If you consider more than one country then flows between countries make things a bit more complicated, but overall change nothing.)

Consider a game of monopoly, because it really is just that simple. All the money tucked under the player’s sides of the table – “private net financial assets” – had to come out of the currency issuer – “government deficits”. For money to go back into the bank – “government surpluses” – it has to come from what the players have – “run down in private net savings”.

So yes, it is precisely the case that government surpluses forced the private sector to run down their savings – where by savings we mean (and always did mean) ‘net financial assets’, which seems pretty uncontroversial. Why, what did you think “running down people’s savings” meant?

Paul Andrews,

Yes I’m the same “ak”

I believe the real advantage of MMT is that it has been shown that the current system can be hacked and the real “debt service costs on the government borrowing” can be set to a very low value if not zero. So the society only needs to worry about the real trade-offs not imaginary ones and is effectively inoculated against debt-deflation. This is one of the points Steve Keen disagrees with the MMT I believe.

The trade-off is obviously the denial of delivery of further free lunches to some rentiers and possibly some moderate erosion in the real value of their assets. This would hurt!

Personally I would put more emphasis not on just stimulating the demand and increasing overconsumption but on stimulating scientific and technological progress to actually reduce the consumption of non-reneweable resources.

But without the MMT and only confined to the reactive quasi-free-market system and we will never address any future problems in time – we will keep doing what we’ve been doing for the last several hundred years, behaving as if there was no environment around us.

There is still a risk that the government will abuse the tools made available by MMT. But this is a political risk – human societies are no longer constrained by dubious database record processing rules claimed as “objective constraints” by the neoconservatives.

begruntled,

Using your definition of people’s savings, people’s savings are people’s claims on others.

By contrast, “Total claims on others” includes firms’ claims on people, as well as people’s savings.

Therefore people’s savings (using your definition) can diminish or increase even though total claims on others nets to zero, and independently of the government’s deficit or surplus.

“The MMT insight is that, since the total value of financial assets is always zero, if the private sector wants to accumulate them (have a net non-zero amount), the government must, as a simple question of logic, be the ones with the corresponding liability. There aren’t any other players at the table! (If you consider more than one country then flows between countries make things a bit more complicated, but overall change nothing.)”

The private sector wants to accumulate real assets. There is therefore no additional insight provided by MMT in this regard.

Hi AK,

If MMT’s core premises can not be shown to be solid then it tells us nothing. Worse, it may be leading people into dangerous misconceptions.

Regarding the environment, measures to negate impacts on the environment need to be judged according to real costs and real benefits. Whether this is done by the government sector or not is probably less important than that it be done. If the objective is to obtain a net real benefit, and the means can be demonstrated to enough people to be likely to be effective, then I agree, it should be done. The big problem is that the costs are borne by individual governments, whereas the benefit is to the whole world, so the cost/benefit analysis doesn’t work for any one country. Therefore some way must be found to persuade many countries to agree on measures and implement them simultaneously. I don’t think the cause is helped by associating it in any way with MMT.

Paul, private sector does not accumulate real assets. It produces real assets and consumes them, then produces more and consumes more. This process of getting more is driven primarily by productivity gains. There is no economic reason whatsoever to accumulate real assets.

Private sector also tends to save. It can only save in something which is external to private sector because any other transaction within private sector is just an asset swap. So this external thing is government liabilities which private sector can not generate. This is the definition of saving.

You can save in real estate, private sector can not. You can save in gold, private sector can not. You can build a house or dig up some gold and consider it your personal savings but it is just a production (GDP) of real estate or gold which is supposed to be consumed. But GDP is a flow. It can not be saved. It is not saving.