I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Income distribution matters for effective fiscal policy

I read a brief report from the US Tax Policy Center – The Debate over Expiring Tax Cuts: What about the Deficit? – last week which raises broader questions than those it was addressing. I also note that Paul Krugman references them in his current New York Times column (published August 22, 2010) – Now That’s Rich. The point of my interest in these narratives is that I have been researching the distributional impacts of recession for a book I am writing. The issue also bears on the design of fiscal policy and how to maximise the benefits of a stimulus package.

Krugman is commenting on the proposal from Republicans and conservative Democrats in the US to force the US Congress to approve the extension of the so-called “Bush tax cuts” that were initially a response to the early 2000 recession caused by the the Clinton surpluses. The tax cuts expire at the end of this year.

Apparently, the tax cuts are worth on average $US3 million “to the richest 120,000 people in the country”.

Krugman says that:

The Obama administration wants to preserve those parts of the original tax cuts that mainly benefit the middle class – which is an expensive proposition in its own right – but to let those provisions benefiting only people with very high incomes expire on schedule. Republicans, with support from some conservative Democrats, want to keep the whole thing.

First, the notion of the tax cuts being an “expensive proposition” is firmly in the deficit-dove nomenclature. In terms of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) such terminology is grossly misleading. The tax cuts just represent “numbers on a bit of paper” and the only issues that are important are the amount of purchasing power that is embodied in the tax cuts (or the reversal of them) and how it is distributed.

From a MMT perspective, the purchasing power question really on matters if we think in real terms – that is, what real resources are at stake?

Second, these questions are in relation to (a) the need to balance nominal aggregate demand growth with the capacity of the real economy to absorb it (relevant to the amount of purchasing power being withdrawn by taking back the tax cut); and (b) the aims of social policy to ensure that the benefits of economic activity are shared in some reasonable manner (relevant to the distribution of the tax burden).

The two issues are interrelated because different income groups have different propensities to consume which influences the impact of fiscal policy.

Krugman seems to acknowledge this when he investigates how the conservatives can justify providing more largesse to rich Americans at a time when they are proposing to savage the federal deficit. He says:

… we’re told that it’s about helping the economy recover. But it’s hard to think of a less cost-effective way to help the economy than giving money to people who already have plenty, and aren’t likely to spend a windfall.

I keep a lot of notes and snippets of information in databases that help me write books and papers. When I read Krugman’s latest blog, I recalled a commentary from one Kevin Drum at Mother Jones (December 16, 2008) – Median Wages – which argued that to get growth back into the economy post stimulus that:

The only sustainable source of consistent growth is rising median wages. The rich just don’t spend enough all by themselves … rich people are going to have to accept the fact that they don’t get all the money anymore. Their incomes will still grow, but no faster than anyone else’s.

On December 17 2008, Krugman’s wrote – Do we need the middle class? – in reply to Drum’s proposed solution that:

I’d say that in terms of strict economics it’s wrong. There’s no obvious reason why consumer demand can’t be sustained by the spending of the upper class – $200 dinners and luxury hotels create jobs, the same way that fast food dinners and Motel 6s do. In fact, the prosperity of New York City in the last decade – largely supported off of super-salaried Wall Street types – is a demonstration that you can have an economy sustained by the big spending of the few rather than the modest spending of large numbers of people.

So less than two years later either economic theory has changed or Krugman has changed his interpretation of it.

The fact is that there has been a lot of economic theory and formal model development which suggests that the spending propensity of the rich will be much lower than for the lower paid.

For example, I recently wrote a blog – Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment – which was about one of the most interesting economists in history. In that blog I alluded to the depth of analysis that Kalecki provided in terms of the theory of the business cycle.

I noted that Kalecki’s theory of effective demand was richer than that which Keynes published a few years later in his 1936 General Theory. Kalecki’s approach had its antecedents in the earlier work of Marx, which was not surprising given that the former had been educated in Poland and was a Marxist economist before heading to the West.

In Kalecki’s work you see that effective demand (aggregate demand) is decomposed into – autonomous expenditure and induced expenditure. So there is some expenditure external to the system (for example, government policy change or export spending) which then induces further expenditure via the spending multiplier. Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point.

The multiplier is based on the insight that the change in induced spending grows by a smaller rate than the initial autonomous spending injection that motivated it. This is because consumers save a proportion of each extra dollar they receive.

The interesting insight that Kalecki introduced into his work was to include a consideration of the distribution of income between wages and profits. So the most basic models assumed that workers saved nothing and profit recipients saved everything. The more sophisticated models in this class allowed workers to save some amount of their extra wages but still have a higher propensity to consume than profit recipients who were also assumed to save some proportion of their income.

In other words, a redistribution of national income can increase or decrease aggregate demand. Kalecki’s insights, in my view, provided more advanced understandings than those offered in the General Theory (Keynes deals with the Propensity to Consume and the Multiplier in Part III, Chapters 8-10. They are worth your time reading.

But back to the Tax Policy Center Report which is predicated on the flawed notion that “(a)s the economy begins to recover from the Great Recession, policymakers must confront the next fiscal challenge: the long-run federal deficit”.

The Report notes that:

In other words, the heated debate over whether to extend all of the tax cuts or whether to extend merely the vast majority largely concerns whether to extend an extra $310,000 in tax relief to the wealthiest 120,000 taxpayers or whether we should instead make a relatively small down payment toward fiscal sustainability.

These calculations reflect the fact that the majority of the tax cuts benefit the top “one-tenth of 1 percent” of income earners.

While I reject the motivation of the Report – which is about how to get the US budget deficit down in the shortest period of time – the emphasis on the distributional impacts of fiscal policy is an important one.

The Report acknowledges that “(s)ince households have different propensities to spend or save out of take-home pay depending on their average income-lower-income groups have a higher propensity to spend- looking at the changes in after-tax income of different groups may also help evaluate how well the extension of the tax cuts will serve as stimulus”.

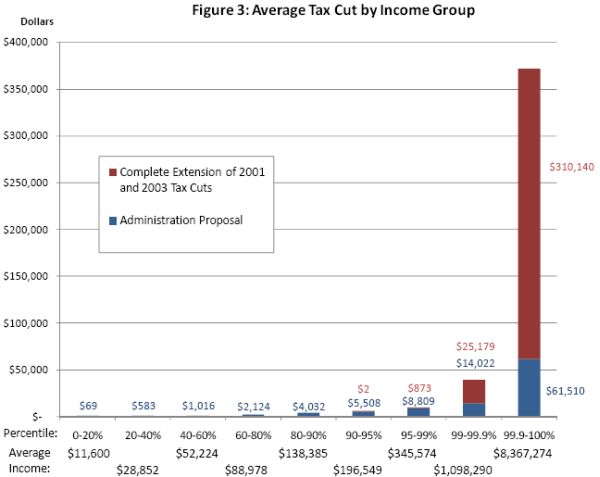

The following graph (Figure 3 from the Tax Policy Center Report) shows the average tax cut by income group. Under the “administration’s proposal”:

… taxpayers in the top 0.1 percent receive an average tax cut of $61,510, taxpayers between 99 percent and 99.9 percent receive tax cuts of $14,021 each, and taxpayers in the middle quintile (40 percent to 60 percent) receive a $1,017 tax break. Taxpayers in the lowest quintile receive an average tax cut of $69.

Whereas, under the complete extension proposal that the conservatives are pushing:

In particular, more than 55 percent of the revenue difference between the administration’s proposal and the full extension of the tax cut accrues to the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers who receive an additional $310,000 each, for a total tax cut of more than $370,000. Those between the 99th and 99.9th percentile also receive substantial increases in the size of their tax cuts under full extension-an additional tax cut of around $25,000, for a total tax cut of around $39,000.

So when considering the aggregate demand impacts of the change in tax rates (an extension or not), the final impact thus depends on the different consumption propensities and the number of people who are affected.

It is not a straightforward case to argue that the rich don’t spend as much so therefore the demand effects of taking away the extension will not damage the overall level of demand.

There is an additional factor to consider. This relates to the discussion above about the two components of a change in aggregate demand following a policy variation.

So a tax cut will inject a certain amount of extra spending into the economy which then induces further spending via the multiplier process. In the blog – Spending multipliers – I note that the multiplier is higher the higher the propensity to consume, the lower the tax rate and the lower the propensity to import.

Imports comprise a leakage from the expenditure stream for income generated by the domestic production process. Just as the overall propensity to consume is dependent on the distribution of income, the overal propensity to import is also sensitive to income distribution. It is highly likely that the higher income groups have a higher propensity to import (per dollar of extra income) than the lower income earners.

So what does that mean? It means that if you put a dollar of extra disposable income into the hands of the lower paid workers the multiplier effects will be greater than if you put the extra dollar into the hands of high income earner because less will be lost to the rest of the world via imports.

So not only will the low income earners spend more of every extra dollar on consumption per se than the high income earners less income will be lost to the rest of the world because the import propensities are also different and align with their consumption propensities.

In a 2008 blog – Some unpleasant Keynesian arithmetic – Harvard academic Dani Rodrik (one of the saner Harvard academics) wrote that:

How much of a boost to economic activity will a fiscal stimulus provide? For those who believe that we have entered a Keynesian world of shortage of aggregate demand–me included–the answer depends on the Keynesian multiplier … It is pretty easy to increase the multiplier; just raise import tariffs by enough so that the marginal propensity to import out of income is reduced substantially (to zero if you want the multiplier to go all the way to 2.8). Yes, yes, import protection is inefficient and not a very neighborly thing to do–but should we really care if the alternative is significantly lower growth and higher unemployment? More to the point, will Obama and his advisers care?

Being the open economy that it is, I fear that the U.S. will have to confront this dilemma sooner or later. In an environment where the dollar has already appreciated against the Euro and even more significantly against emerging market currencies, fiscal stimulus here will produce an even larger current account deficit. If American consumers decide to spend 40 cents of a dollar of additional income on cheap imports from China and other foreign countries, the multiplier will be a mere 1.3. How long will it take before politicians of all stripes cry foul over the leakage through the trade account and the “gift to foreigners” that this represents? And they will have Keynesian logic on their side.

While I wouldn’t follow Rodrik’s plan to increase the value of the multiplier, the point is relevant when considering whether you support the extension of the tax cuts to the rich or not.

Recessions and inequality

The research that underpins this blog was actually motivated by some work I am doing on the impacts of recession on inequality. The other way of thinking about this motivation is to ask the question: Who bears the brunt of an economic downturn?

Please read my blog – Where the crisis means death! – for more discussion on this point.

The literature is very clear. For example, UK economist Tony Atkinson wrote an interesting article in the OECD Observer (No 270/271 December 2008-January 2009) entitled – Unequal growth, unequal recession?. He said:

Whether the burden of any recession is felt by some social groups and countries more than others depends largely on public policy.

This is a very significant point. Recessions tend to impact negatively on the most disadvantaged cohorts in the society because they disproportionately bear the burden of unemployment and the associated income losses. When you add the wealth losses that accompany joblessness the income inequality generalises to rising wealth inequality.

But the policy response can attentuate much of these adverse impacts.

Atkinson reports that a OECD report released in October 2008 – Growing Unequal? – found that during the growth period leading up to the recession that:

A rising tide does not necessarily raise all boats. Or, to use another liquid metaphor, we cannot rely on trickle-down … few OECD countries have reduced inequality over the past 20 years. The past five years saw growing inequality and poverty in two-thirds of OECD countries …

The major reason for this growing inequality relates to poor policy design that allowed high income cohorts to expropriate disproportionate shares of the growing real income. Real wages growth for workers has been suppressed and muted for the last two decades as the profit share has expanded. This dynamic has been supported by deregulation of labour markets and financial markets.

Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The distributional shift that occurred over the recent growth period was accompanied by an obsessive reliance on monetary policy and passive fiscal policy which erred on the side of producing surpluses. Further, the private sector indebtedness reached record levels in many nations. All of these “unprecedented” occurrences were interrelated and unless government reverse them there will be another crisis in the not to distant future (or an prolonged extension of the current crisis).

Atkinson noted that history shows that in past crisis the:

… the share of the top 1% changed following the Great Crash of 1929. This did indeed affect the rich, who had prospered in the Roaring ’20s. In a number of countries, top income shares fell: in the US, the shares of the top 0.1 and 0.01% were reduced by between a quarter and a third. Top income shares fell in Australia, France, the Netherlands and the UK. But they did not fall universally, and, as the Great Depression ensued, other income groups were seriously affected.

If, today, recession follows, then we can look at more recent experience of the distributional impact of unemployment, although it means going back before the mid-1980s. By then, unemployment in Europe was around double that in the 1970s and four times that in the 1960s. From this rise in European unemployment, we learned that the impact on household living standards depended on government policy. It was not inevitable that unemployment led to mass poverty.

Here the OECD report … concludes that the rise in market-income poverty from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s was, at least in part, offset by increased government redistribution. But between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, when market-income poverty stopped rising, the redistributive effect of transfers and taxes fell back, leading to higher poverty rates based on disposable income-that is, the income people actually have to spend or save.

The point is that I consider the design of the fiscal stimulus packages should reflect two concerns.

First, they should unambigously target the spending gap that results from the collapse of private demand. Relying on export-led recovery will not work when the whole world is depressed. So the quantum of the projected fiscal stimulus should be adequate and the tapering of it should be such that it allows private spending to resume in a calibrated manner.

Second, the stimulus packages should also ensure that all boats rise in the tide and where losses occur they are proportionate.

The extension of the Bush tax cuts for the rich would not serve this second goal given the unemployment that abounds in the US and probably doesn’t advance the first goal effectively for reasons already discussed.

Atkinson said:

There is a message for policy today. Government budgets are under stress, but citizens are going to expect that, if funds can be found to rescue banks, then governments can fund unemployment benefits and employment subsidies. If governments can take on the role of lender of last resort, then we should be willing to see government as the employer of last resort. Put bluntly, governments have to step up to the plate, as Roosevelt did in the Great Depression.

As regular readers will appreciate, I am totally in agreement with this viewpoint.

The starting point for any macroeconomic policy design should be to introduce a buffer stock of jobs – I call this approach the Job Guarantee.

This provides the minimum fiscal support for full employment in terms of the unconditional provision of a minimum wage to anyone who desires a job under those conditions and cannot find one. It is not a universal panacea but an essential safety net to reduce the inequality that arises during a recession.

Please read my blogs – When is a job guarantee a Job Guarantee? and Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment – for more discussion on this point.

It is clear that the design of the fiscal stimulus packages have fallen short of my ideal both in scale of impact and their distributional focus.

But progressives should keep the focus on fiscal policy!

In the context of this discussion, I also note that “progressive economist” Dean Baker from the US-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research is still arguing for variations in monetary policy.

He wrote in the UK Guardian article (August 23, 2010) – Ben Bernanke: Wall Street’s servant that:

… the Fed should be taking aggressive steps to bring the economy back to full employment … Its chairman, Ben Bernanke, even knows exactly what needs to be done … He wrote a paper back in 1999 about Japan’s stagnant economy and mild deflation … [and] … urged Japan’s central bank to target an inflation rate in the range of 3-4%.

A rate of inflation in this range would substantially reduce real interest rates, giving firms a powerful incentive to invest.

With interest rates at around zero, the US central bank would have to achieve this aim via inflating expectations. That is, signalling to the households and firms that it will keep nominal interest rates down to allow the inflation rate to increase and stabilise at a higher level.

This is a very orthodox way of thinking and doesn’t bear scrutiny.

Monetary policy is not an effective vehicle for stimulating aggregate demand. With private spending so low as a result of the pessimism about the future is hardly going to be addressed by an expectation that real interest rates will be lower.

Further, the uncertainty about who wins (debtors) and who loses (creditors) when rates fall and the macroeconomic impact on overall spending makes monetary policy a very inexact tool to use when there is a deep recession.

Conversely fiscal policy can be designed to place spending capacity into the hands of those who will use it the most and thus can exploit distributional knowledge. It is thus a more flexible and targetted policy tool.

One of the problems of the current stimulus packages that nations introduced is that they were not well targetted and so there was leakage from the expenditure stream as a result. For example, in the US too much of the policy initiatives have been targetted towards the top-end-of-town.

Finally, this proposal is as much a “red rag” to the neo-liberal bulls as that which says the US (and other governments) should expand fiscal policy. So why does a progressive economist not continue to focus on the political constraints that are crippling fiscal policy at present rather than buy into the orthodox argument that “monetary policy is the only thing we have left”?

I think that is tactically, a very unfortunate concession for a progressive to make.

Baker does make a sound point that the reason Bernanke won’t do this is because:

For the Wall Street bankers, everything is just fine now. If Bernanke were to pursue a policy of targeting 3-4% inflation, it could erode the real value of many of their assets. These banks own mortgage debt and other assets whose value would be reduced by even modest rates of inflation. While targeting a slightly higher rate of inflation may be a no-brainer from the standpoint of workers and most of the country, it is not good for Wall Street – and this is who our supposedly independent Fed is answering to.

Conclusion

In thinking about fiscal policy I am also reminded of a lovely quote at the end of Chapter 10 of Keynes’ General Theory where he deals with the propensity to consume and the multiplier.

On the self-imposed difficulties modern economies face when dealing with unemployment, Keynes said:

Ancient Egypt was doubly fortunate, and doubtless owed to this its fabled wealth, in that it possessed two activities, namely, pyramid-building as well as the search for the precious metals, the fruits of which, since they could not serve the needs of man by being consumed, did not stale with abundance. The Middle Ages built cathedrals and sang dirges. Two pyramids, two masses for the dead, are twice as good as one; but not so two railways from London to York. Thus we are so sensible, have schooled ourselves to so close a semblance of prudent financiers, taking careful thought before we add to the “financial” burdens of posterity by building them houses to live in, that we have no such easy escape from the sufferings of unemployment. We have to accept them as an inevitable result of applying to the conduct of the State the maxims which are best calculated to “enrich” an individual by enabling him to pile up claims to enjoyment which he does not intend to exercise at any definite time.

That is worth thinking about.

Anyway, I have run out of the time I allocate to my blog today and we have a guest staying with us tonight and I have to make a banana cake! So ….

That is enough for today!

I think it is about time that we tried ‘bubble up’ given that ‘trickle down’ has been such an abject failure.

Yes, but it is important that when we do bubble-up we avoid tunnel-through 🙂

“… So why does a progressive economist not continue to focus on the political constraints that are crippling fiscal policy at present rather than buy into the orthodox argument that “monetary policy is the only thing we have left”?

I think that is tactically, a very unfortunate concession for a progressive to make.

Very well stated.

I hope that the “one Kevin Drum” gets pulled to this site to learn a bit more about true progressive economics.

“It is highly likely that the higher income groups have a higher propensity to import (per dollar of extra income) than the lower income earners.”

Why would this be so? It is not obvious to me. The current incipient recovery in America has been marked by a large surge in imports. Is this because the recovery has been largely limited to those with relatively high incomes? I would like to see some evidence to that effet before I could conclude that higher income groups have a higher propensity to import than the lower income earners.

This is just anecdotal, but lower income workers tend to shop at stores that derive a significant portion of their wares from abroad like Walmart and Target. This seems to me to imply that the propensity to import would be higher for low income workers. Does anyone know of any research dealing with propensities to import by income group?

Thank you for the comments on Kalecki.

Now, if you are someday struggling for a good topic, I would suggest that a like piece on Gunnar Myrdal and the Swedish School would be most welcome.

I’ll second that (Myrdal).

Interesting how neo-liberals never question the marshall-lerner condition with respect to Australia and yet jump all over Bill when he merely makes a suggestion that “It is highly likely that the higher income groups have a higher propensity to import (per dollar of extra income) than the lower income earners.”

Bill, so much better than PK’s blog on the same subject, as are all your blogs on comparable issues. They gave the wrong person the Nobel.

Hi Bill,

This discussion of income distribution moves me to ask whether MMT has anything to say about the issues of price determination, distribution of income/surplus between labour and capital, and returns on “factors of production”. I tend to rely on Sraffa’s demonstrations that a set of market-clearing prices can be found that is compatible with any division of surplus between wages and profits, and that the idea of a marginal price of capital is a myth, when discussing such things. But Post-Keynesian thinking has probably moved beyond Sraffa in ways that I am unaware of.