I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Fiscal austerity – an interesting test is coming

The coming period will be an interesting test. I say interesting in the sense of an intellectual curiosity rather than anything that my sense of humanity might find to be acceptable. I am referring to the widespread acceptance by politicians around the world that fiscal austerity is good for growth. Governments are increasingly getting bullied into adopting austerity measures apparently thinking they will help their economies grow. My bet is that the austerity measures will undermine growth and when growth finally returns it will be tepid and as a result of other factors not related to the austerity. In the meantime there will be massive casualties among the poor and disadvantaged. So if the Flat Earth Theorists (FETs) are correct in a few months we should be seeing rapid growth and reductions in the deficits. Of the countries that have led the charge (for example, Ireland) things don’t look good for the FETs. So we will see. If they are wrong you can be sure that various ad hoc responses to anomaly will be forthcoming. For example, I lost my briefcase on the way to work which had a key to growth in it! Excuses like that. The mainstream have never and will never admit they are wrong. The task will be to show the people that this rabble of economists should be ignored.

In today’s Wall Street Journal (June 18, 2010) former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan was making the case for austerity – U.S. Debt and the Greece Analogy. Please read my blog – Being shamed and disgraced is not enough – for more discussion on what I think of Greenspan strutting the public stage still.

Greenspan says that we should not “be fooled by today’s low interest rates. The government could very quickly discover the limits of its borrowing capacity” and that:

An urgency to rein in budget deficits seems to be gaining some traction among American lawmakers. If so, it is none too soon. Perceptions of a large U.S. borrowing capacity are misleading.

Despite the surge in federal debt to the public during the past 18 months … inflation and long-term interest rates, the typical symptoms of fiscal excess, have remained remarkably subdued. This is regrettable, because it is fostering a sense of complacency that can have dire consequences.

Which tells me that there is no fiscal excess in the US. How could there be when the unemployment rate is 9.7 per cent (May 2010) and the broader measure of labour underutilisation is above 16 per cent.

But I liked the turn of phrase – it is regrettable that things are not going bad as the deficits increase and people might start to realise that the FETs deficit hysteria is just that – an hysterical, ill-informed knee-jerk.

His main argument is that the bond markets will soon punish the US government – “(h)ow much borrowing leeway at current interest rates remains for U.S. Treasury financing is highly uncertain”.

So when you haven’t any case to make you just introduce “uncertainty”. I would bet that the leeway is greater by far than the US government would ever have to borrow!

At least Greenspan makes one correct point, which is usually lost on the FETs:

The U.S. government can create dollars at will to meet any obligation, and it will doubtless continue to do so. U.S. Treasurys are thus free of credit risk. But they are not free of interest rate risk. If Treasury net debt issuance were to double overnight, for example, newly issued Treasury securities would continue free of credit risk, but the Treasury would have to pay much higher interest rates to market its newly issued securities.

So there is no risk of solvency. That should have been headlines. There is no sovereign debt risk in the US.

It is also clear that under the current institutional mechanisms that the US and other governments use to issue debt (including private auctions) the bond markets do have a say in setting the yields on public debt. Please read my blog – On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that should this unnecessary and voluntary system ever get in the way of the government’s ability to do what it wanted – there would be a change in the institutions. I would doubt that a sovereign government would ever allow itself to be permanently controlled by the bond markets.

The most simple way under the current institutional arrangements was outlined in my blog – Operation twist – then and now. I noted that in a 2004 paper written by Ben Bernanke, Vincent Reinhart, and Brian Sack – Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: An Empirical Assessment – the authors examine the future of monetary policy when short-term interest rates, the principle tool of monetary policy get close to zero (as they are now).

They seek to explore whether alternative strategies would be effective when the short-term interest rate was zero. One policy alternative that can be effective is changing the composition of the central bank’s balance sheet “in order to affect the relative supplies of securities held by the public.”

The authors note that the:

Perhaps the most extreme example of a policy keyed to the composition of the central bank’s balance sheet is the announcement of a ceiling on some longer-term yield, below the rate initially prevailing in the market. Such a policy would entail an essentially unlimited commitment to purchase the targeted security at the announced price.

It is also interesting that the authors (in a footnote on page 25) say that “In carrying out such a policy, the Fed would need to coordinate with the Treasury, to ensure that Treasury debt issuance policies did not offset the Fed’s actions.” So as long as the government operates as a consolidated policy sector their actions will be self-reinforcing.

Mainstream economists have eschewed this sort of strategy and claim that the only way this could be successful would be if it ratified the market. That is, the only way the central bank could “enforce a ceiling on the yields of long-term Treasury securities” would be if the “targeted yields were broadly consistent with investor expectations about future values of the policy rate”.

So Greenspan’s conclusion is heavily predicated on the assumption that the central bank will not operate outside the little neo-liberal box which sees it manipulating interest rates (and causing unemployment) to fight inflation.

The rest of Greenspan’s arguments are about movements in spreads between public and private debt which are largely irrelevant once you realise the government is in charge.

Later in the article there are some interesting points. In talking about the ageing population and the implications for fiscal policy, Greenspan says:

We cannot grow out of these fiscal pressures. The modest-sized post-baby-boom labor force, if history is any guide, will not be able to consistently increase output per hour by more than 3% annually. The product of a slowly growing labor force and limited productivity growth will not provide the real resources necessary to meet existing commitments. (We must avoid persistent borrowing from abroad. We cannot count on foreigners to finance our current account deficit indefinitely.)

Only politically toxic cuts or rationing of medical care, a marked rise in the eligible age for health and retirement benefits, or significant inflation, can close the deficit. I rule out large tax increases that would sap economic growth (and the tax base) and accordingly achieve little added revenues.

Several things are to be noted here.

First, foreigners will stop net exporting to the US when they have accumulated enough US-dollar denominated financial assets. In the meantime, the US citizens can enjoy the real booty. It is true that if the foreigners do saturate their desire for US-dollar financial assets then there will be real cuts in the US standard of living. Enjoy it while you can. I doubt that day is coming any time soon.

But from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, the correct way of thinking about it is that the US consumers are “financing” the foreigners desire to accumulate savings in US-dollar denominated assets.

Second, his ideological propensities are on display. The free market lobby hate taxes. But the empirical evidence is that cutting spending is worse for aggregate demand than increasing taxes because some of the tax rise is taken out of saving. A spending cut is a $-for-$ cut in demand – direct and fast.

Third, the point about running out of real resources is the interesting one. That since sentence is actually what the intergenerational debate should be focused on. The current focus on financial matters is erroneous. The question will always be – will the production system at some future date be able to produce enough real goods and services to satisfy the demand for them?

Thinking about that leads one to conclude that the last thing you would want to be doing now is to cut public investment in technology and education. Those two areas of investment will provide the know-how and the skills to lift productivity in the future.

Further, leaving huge proportions of your willing labour force idle is not the way to deal with the future. Government should aim to maximise income in each period to create as much private saving as is desired.

Finally, if there is a shortage of real goods and services in the future it doesn’t follow that you would want to have less public command over them. It might be a better option to reduce output of the private Walmart type products in favour of more sophisticated public provisions of health and aged care. Ultimately, all these allocation decisions are political anyway.

And Greenspan leaves us with no doubts that he is a FET:

The United States, and most of the rest of the developed world, is in need of a tectonic shift in fiscal policy. Incremental change will not be adequate. In the past decade the U.S. has been unable to cut any federal spending programs of significance. I believe the fears of budget contraction inducing a renewed decline of economic activity are misplaced .. Fortunately, the very severity of the pending crisis and growing analogies to Greece set the stage for a serious response …

So the Greek conflation error again and a blind belief that if you cut spending the economy will grow. It will not!

Sayonara Japan …

But the idea is catching on. The Wall Street Journal carried the story yesterday (June 17, 2010) – Japan’s DPJ Unveils Platform – which reported that:

Japan’s new prime minister told voters to brace themselves for the pain of a major tax increase as a way to avoid a Greek-style debt crisis, adopting a higher sales tax as the centerpiece of his economic and political platforms.

Accordingly, the Japanese government is planning to fast-track a doubling of the “sales tax from the current 5% over the next few years” and has reneged on a promise that it would wait until 2013 before it considered increasing the consumption tax.

The Government is claiming tha this will allow Japan to achieve a 3 per cent nominal GDP growth rate over the next decade “a level Japan hasn’t seen since the early 1990s”.

The Government will also “cap next year’s debt issuance at the current fiscal year’s level and aim to balance its main budget within 10 years”.

The Prime Minister said in releasing his new growth strategy:

We can’t be an idle spectator of the turmoil in Europe started by the fiscal collapse in Greece

So you can see how far this Flat Earth Theory (FET) thinking has permeated. Here we have the PM of the second largest economy in the world (soon to become the third largest) which is totally sovereign in its own currency and as such has no solvency risks saying that a small European nation that is part of a monetary union is an comparitor.

There is no legitimate comparison between a nation that does not issue its own currency, does not set its own interest rate and does not have a flexible exchange rate (any EMU nation) and Japan.

The tragedy that the commentators are drawing this connection every day now as the pressure on fully sovereign nations to cut back is mounting.

The proponents of the tax hike in Japan say that “the rate of the tax in Japan is far lower than in most other developed nations … [and] … it’s so broad-based that a small increase will instantly boost tax revenues”.

The level has nothing to do with the likely marginal impact. It is the change that will impact. Consumers have adjusted to the current level. They will now face a sudden drop in their purchasing power and theory tells us that they will react by reducing spending.

A bank economist responding to the predictions that it would “increase the tax revenue annually by 10 trillion yen ($110 billion)” said:

That’s a substantial amount and definitely positive for the debt market …

Lets assume it is “positive” for the debt market – all this tells me is that priorities of the “debt market” are not those that a government should adopt or pander too when it is seeking to advance public purpose. Being forced to reduce economic activity when it is already close to a sustained recession is not in the interests of the citizens of that country.

As I noted at the outset, as these tensions increase – between what the amorphous debt markets deem suitable and what is best for the nation as a whole – a new discourse may open up challenging the whole neo-liberal obsession with a sovereign government issuing debt when it clearly doesn’t have to.

In terms of the sales tax hike, Japan has been down this road before and appears not to be learning from its past mistakes.

An opposition politician made the obvious point that the move will damage consumption:

Boosting the economy with a tax hike? That’s an obscene stretch …

And another academic critic said:

What I am afraid of is the return of the 1997 experience … The economy may seem to be doing fine right now but it still has weak spots and the recovery is propped up by government stimulus plans …

So what happened in 1997?

In the 1990s, as Japan was struggling to grow again after its property collapse, the pressure mounted on the government to cut its growing deficit. All the same arguments were presented then as now.

The “Ohira shohizei curse” is named after the 1970s Prime Minister (Ohira) who tried to introduce a consumption tax in Japan and his party lost its majority in the 1979 as a result of voter backlash (shohizei is the name for sales tax).

However, in the late 1980s, a 3 per cent tax was introduced and this again damaged the leadership of the government politically. The political damage continued in 1994 when the then Prime Minister tried to increase it to 7 per cent.

But the FETs were out in force as the deficit rose in the second-half of the 1990s and in 1997 the government pushed it up to 5 per cent. The so-called “lost decade” was firmly entrenched as a result.

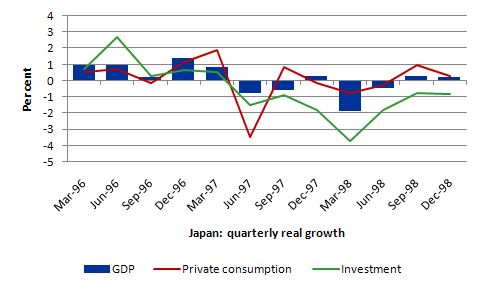

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage growth in real GDP, real private consumption and real private investment in Japan between March 1996 and December 1998. The datat is taken from the OECD Main Economic Indicators.

This is what the “Ohira shohizei curse” is about. You can see that private consumption responded to the tax hike negatively and this impact endured for several quarters into 1998 (albeit with one quarter of modest recovery) until the government recanted and implemented a new fiscal stimulus. The situation was made worse by the fact that private investment also fell as overall growth plummetted.

While there is a lot of bravado among those calling for the spending cuts and/or tax hikes, they are yet to offer any coherent explanation as to why the obvious outcome will not apply this time. With the world mired in recession or tepid growth and little sign of a private spending comeback, the dangers of a private consumption reversal in Japan are even greater now.

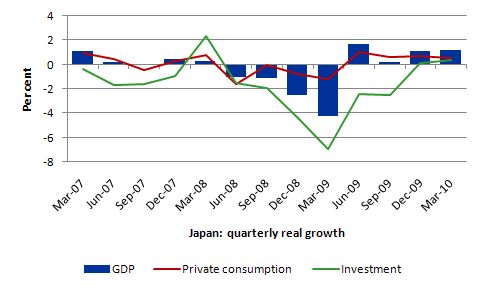

The next graph shows the same growth series for Japan from March 2007 to March 2010. As you can see there is only the most fragile recovery evident in Japan at present. It is highly likely that reducing the spending capacity of consumers will repeat the disastrous 1997 episode. A major difference between now and then was the behaviour of exports. While they slowed considerably in 1997, the collapse in growth in the December 2008 quarter (-14.2 per cent) and the March 2009 quarter (-24.8 per cent) was unprecedented.

The fact that the Japanese government are prioritising what they perceive to be the demands of the bond markets is part of the general trend towards the supremacy of the largely unproductive financial markets in determining policy outcomes. This point was raised by the biographer of J.M. Keynes, Robert Skidelsky wrote in the Financial Times (June 16, 2010) – Once again we must ask: ‘Who governs?’

In the 1970s, as the neo-liberal rise to policy dominance was beginning the vehicle they used regularly was to raise the spectre of “union power”. As Skidelsky says:

In 1974, Edward Heath asked: “Who governs – government or trade unions?” Five years later British voters delivered a final verdict by electing Margaret Thatcher. The equivalent today would be: “Who governs – government or financial markets?” No clear answer has yet been given, but the question may well define the political battleground for the next five years.

I discussed this issue some months ago in this blog – Who is in charge?.

Skidelsky notes that underlying the calls for austerity is the old classical belief that “market economies are always at, or rapidly return to, full employment.” So the mainstream macroeconomics textbook considers policy interventions to be largely a waste of time because the economy will deliver desirable outcomes anyway.

This is the argument that was presented during the 1930s Depression – the “famous “Treasury view” of 1929″. The debate then which has become known as “Keynes and the Classics”. The “Treasury View” failed to deliver policies that solved the Depression and the application of the same sort of policies, which is being advocated now, will also make things worse.

I deal with that debate in detail in this blog – What causes mass unemployment?.

Skidelsky points out that:

By contrast, Keynes argued that demand can fall short of supply, and that when this happened, government vice turned into virtue. In a slump, governments should increase, not reduce, their deficits to make up for the deficit in private spending. Any attempt by government to increase its saving (in other words, to balance its budget) would only worsen the slump.

This viewpoint became the dominant policy perspective in the full employment era following the end of World War II.

But here Skidelsky introduces an interesting nuance. Apart from the Chicago and Harvard ideologues who just push their own work, Skidelsky says that the main driver of the current call for austerity is a claim that governments have:

… to restore “confidence in the markets”. The argument here is that deficits do positive harm by destroying business confidence. This collapse of confidence may come in several forms – fear of higher taxes, fear of default, fear of inflation. Deficits thus delay the natural (and rapid) recovery of the economy. If markets have come to the view that deficits are harmful, they must be appeased, even if they are wrong. What market participants believe to be the case becomes the case, not because their beliefs are true, but because they act on their beliefs, true or false.

So it is about expectations. And the FETs know that the louder they shout and the more mindless media lackeys they can invoke to spread the shouting the stronger the fears will become. It doesn’t matter that there is no substance in any of these fears. That seems to be what is going on at present.

Skidelsky notes that this was rehearsed 1931. The UK Conservative-Liberal coalition “introduced an emergency budget in September 1931” which Keynes described in this way:

… replete with folly and injustice … every person in this country of super-asinine propensities, everyone who hates social progress and loves deflation, feels that his hour has come and triumphantly announces how, by refraining from every form of economic activity, we can all become prosperous again.

There is nothing new about all this. Britain went backwards in 1931 and ultimately had to abandon the gold standard and the resulting depreciation of the currency stimulated exports enough to get some growth going. But the real growth did not come until the war spending in the late 1930s. But the conservative approach was a total failure.

In this sense, Skidelsky says:

We are about to embark on a momentous experiment to discover which of the two stories about the economy is true. If, in fact, fiscal consolidation proves to be the royal road to recovery and fast growth then we might as well bury Keynes once and for all. If however, the financial markets and their political fuglemen turn out to be as “super-asinine” as Keynes thought they were, then the challenge that financial power poses to good government has to be squarely faced.

Conclusion

It is too early to tell but the current situation might reach a stage where the population start to realise that when the governments bend to the amorphous bond markets they are deliberately undermining the general welfare of the people.

I think the Greeks are realising this. The Spaniards will soon. But in every country the aim is to broadcast this high and low. It is also essential that people understand that the constraints on governments are voluntary and only serve the interests of the top-end-of-town.

Then the debate might broaden. What is desperately needed are new think-tanks on the progressive side that can really prosecute the case properly.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

“Of the countries that have led the charge (for example, Ireland) things don’t look good for the FETs.”

Ireland is not a good example in that it’s main problem is arguably its need to devalue its currency, which it is doing by cutting wages in public sector presumably in the hopes that the private will follow. This a silly policy for Europe as a whole, but it could enable Ireland to pinch business from the rest of Europe. Bill: don’t put your eggs in the Ireland basket!

Re Bill’s remarks about Alan Greenspan, both Greenspan and Bill are wrong. Greenspan is saying, to paraphrase, “Stimulus comes from having government borrow and spend. There is a limit to how much government can borrow, and we could be near that limit. Thus interest rates might shoot up, so we better rein in.” (U.S. national debt just after WWII relative to GDP was over double its present level! But never mind.)

Bill says, to paraphrase, “Unemployment is high, therefore the deficit cannot yet be anywhere near large enough.”

I suggest the reason for the coexistence of huge increases in national debts in several countries combined with stimuli which have been barely adequate is desperately simple: crowding out.

MMT’s answer to the latter problem is or should be equally simple: just don’t have government borrow! Crowding out results from borrowing. No borrowing means no crowding out. Certainly Milton Freidman’s 1948 version of MMT and Warren Mosler’s involve no borrowing. I agree with them. Instead of borrowing, just have the government central bank machine print and spend extra money (and if inflation looms, do the opposite: raise taxes and extinguish money).

Also Abba Lerner, as I understand it, only advocated government borrowing and interest rate policy as a means whereby government could bring the optimum amount of investment. That strikes me as daft: the idea that politicians or bureaucrats or anyone else knows the optimum interest rate or amount of investment, is pie in the sky. Presumably Lerner would not have advocated government borrowing “as a source of funds”.

Bill: don’t try to defend borrowing on the grounds that crowding out is not problem. You are skating on thin ice you don’t need to skate on.

Mosler: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/warren-mosler/proposals-for-the-banking_b_432105.html (See his 2nd last para.)

Friedman: http://www.jstor.org/pss/1810624

Ralph,

I presume that is why ‘Quantitative Easing’ is a silly policy, since it doesn’t nothing other than inject money into the financial markets.

Neil: what’s really funny about QE (as far as I’m concerned, as a advocate of MMT) is that QE constitutes a move by governments towards MMT. That is, they discovered in 2009 that having government borrow and spend wasn’t working as well as hoped, so they went for QE which is money printing of a sort. My message to governments is “Well done chaps: you’re getting there slowly”.

While I understand the innocent fraudsters view about financing and that it is a fraud, I believe the day is already here. The fact that the innocent fraudsters claim that since we (as in the US, not me) “cannot keep borrowing dollars” and hence the current account is bad is illogical, that doesn’t mean that current account deficits are good.

There are many money issuing authorities in the US, for example foreign banks. The question of who’s lending whom or who is financing one thing, the question of how fiscal policy is effective (given the external sector and the dollar’s value versus other currencies) another.

Consider the scenario where the fiscal stance is relaxed. Either the pure government expenditures is increased or the tax rate is reduced or both. An expansionary fiscal stance leads to a positive S – I in the short term, but sends it back to zero or the negative territory in the long term.

“An expansionary fiscal stance leads to a positive S – I in the short term, but sends it back to zero or the negative territory in the long term.” according to Ramanan.

Ramanan: given constantly changing levels of confidence and a constantly changing private sector desire to leverage or deleverage, what makes you think you can predict S – I in the short or long term? Indeed, why even bother trying?

If demand is deficient, have government print money and spend it (and/or cut taxes, e.g. do a Mosler payroll tax cut). Conversely if inflation looms, do the opposite.

BTW there is someone else I should have added to the above Friedman / Mosler list and that is Randall Wray. See:

http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP22-Wray.pdf

Ralph,

I have read your comments and am not sure why you have some soft corner for the monetary base. Secondly, I wouldn’t use the phrase “print money”, because money is printed on demand.

While it is true that the parameters of the private sector keep changing all the time, and it is silly to predict the future, there are some things one can say about the likely future scenarios. Of course, all mainstream economists do it all the time, but that is useless since they do not even get the accounting right.

Not sure what you are trying to say here.

Also, my comment @19:48 was a bit specific to the US.

Greenspan did make one statement that will probably go unnoticed by the FETs but is an important (inadvertent maybe?) concession………….

“Despite the surge in federal debt TO the public during the past 18 months ……” (capitalization mine)

How many times have we heard that the federal debt is a burden ON the taxpayers? Now we have their old wise sage slipping up and saying, actually its the taxpayers who are RECEIVING the money!

I think this is significant.

Ramanan: Re the phrase “print money”, I assume that what you object to is that this might be taken to refer just to the physical printing of dollar bills. If so, good point. I’ll use the phrase “create money” instead.

The reasons I have a “soft corner” for the monetary base and oppose national debts are as follows (which I imagine are similar to the reasons given by Friedman, Mosler and Randall Wray, though I cannot speak for them, and cannot quote off the top of my head from their works).

1. There is no need to pay interest on monetary base. I realise that some central banks have, or have said they might pay interest on the MB. I don’t know why they bother.

2. Expanding the monetary base definitely expands private net finance assets (pnfa), which is one reason it should boost demand. It is debatable as to whether expanding the national debt also expands pnfa. This is because while the debt itself is certainly an asset for private sector holders of debt, the value of this asset is based at least partially on the fact that interest is paid on for example Treasuries. But this is countered by an equal obligation in taxpaying non-holders of the debt to pay taxes to fund the interest. I.e. non-debt holders are loaded with a liability. If what Greg (just above) says is right, it looks like Greenspan has just tumbled to this point. As I said above in reference to governments, “well done chaps, you’re getting there slowly”!!

3. The effect of “create money and spend it” (or cut taxes) is more certain than having government borrow and spend. This is because there is a large amount of disagreement on how serious crowding out is. By “crowding out” I mean government borrows more (and spends the money) but leaves other things equal. This tends to raise interest rates and/or make it more difficult for private sector would be borrowers to borrow. Of course in 2009 governments borrowed more and promptly (at least in U.K.) QE’d the securities they just issued. Thus in 2009 other things were not equal.

Bill:

I agree this is a turning point in the global financial crisis (v 1.0) – and with the recent discussions over bond markets, borrowing vs. spending timing/relevance, capital distribution of income at zero rates, etc. that we have been having over the last few weeks, I am more convinced that the political constraints as reflected through institutional mechanisms and ideological justifications regarding what “is possible” sometimes make me wonder if we can also apply MMT principles as a foundation to understanding some of these political actors in a more analytic fashion.

For example, while “audit the Fed” is a great populist slogan – I actually believe that the Fed is fairly transparent in relation to other institutions. I would much rather see calls to “audit the bond market”, but I must admit I don’t know how to frame such a demand.

So, does it make sense to investigate the financial mechanisms/processes of other actors (e.g., “the bond market”) in a deeper framework? And this might be an appropriate forum to do so?

Clearly from the graphs above, as public spending increased, private investment decreased. What is correlation, causation, and what is political spite (bond markets “withdrawing” to punish the public)? Now “spite” isn’t much of an explanation, there must be forces beyond ideology in play that drive these actors to their positions.

For example, I believe there is some kind of immense value realization gap (for lack of a better term) that the financial system cannot absorb without serious implosion. This is only supposition – I don’t have the context (nor the chops to build one) to dive into details to develop a better explanation.

The theoretical MMT foundation is incredibly powerful, but might there be room for extension to understand how private subjective forces function and perhaps better explain and forecast potential actions/outcomes? For me (a neophyte), MMT has been an immense help understanding the current economic and financial landscape, much better than anything I have found.

But I am often frustrated by the prescriptive discourse (“government spending”), which of course is correct, without another dimension that describes why this is impossible/improbable under the current social/political environment – one in which our existing political institutions are unable to shift. But I am unsatisfied with corruption (yes, it exists) or ideological blindness (yes, it exists) to explain the political impasse – I think there is something more fundamental at work.

But I guess my question is if it is possible to create an understanding beyond “corruption” and “captured by neo-classical economic theory”, instead directed toward deeper, evolving structural forces manifesting themselves in specific historical formations. And of course I wonder if MMT the appropriate context/foundation to start building such an analysis?

Finally, I just want to add that the level of discourse, the intellectual integrity and the personal respect consistently displayed by the participants in this blog community is incredible. It is a rare gem in the blog world. This is a powerful resource you have developed, I am fortunate to have found it and I value it highly.

pebird: But I guess my question is if it is possible to create an understanding beyond “corruption” and “captured by neo-classical economic theory”, instead directed toward deeper, evolving structural forces manifesting themselves in specific historical formations.

Historical forces are difficult to discern other than in hindsight. Are we in late-stage capitalism, preparing to shift to a new system whose outlines are as yet unclear? Or is now mature capitalism the paradigm for globalization? There are a lot of possibilities being discussed right now, and most prognosticators are talking their own book. There are also a lot of possibilities that aren’t being discussed.

Good theory is reality-based. That is to say, its explanatory and predictive power is grounded in accurate description. As a stock-flow consistent macro theory, I’d say that MMT is superior to theories that are based on assumptions that are not as solidly grounded in empirical evidence, and which sometimes seem to contradict the evidence.

But can MMT foretell the future? No. There are too few accurate data, too many variables, too much uncertainty, and too much complexity to model with any great degree of accuracy, given the present stage of human and technological development. And then there are the unexpected shocks resulting from “acts of God,” hidden assumptions, unintended consequences, etc.

When I say “human development,” I mean that we don’t even understand ourselves sufficiently to know how we behave. A great deal of economic theory is based on inadequate notions about this. While disciplines like cognitive science are rolling back the horizon of knowledge, they are also revealing how much we don’t yet know about the complexity of brain functioning and human interaction. As George Soros observes in his theory of reflexivity, this is crucial, since our ideas and actions create feedback that influences events in unexpected ways.

Maybe I’m confused, but I think the sentence:

“But the empirical evidence is that cutting spending is worse for aggregate demand than increasing taxes because some of the tax CUT is taken out of saving.”

Should read:

But the empirical evidence is that cutting spending is worse for aggregate demand than increasing taxes because some of the tax INCREASE is taken out of saving.

Dear Nklein1553 at 2:09

Yes! Appreciate your scrutiny. My typo.

best wishes

bill

“By “crowding out” I mean government borrows more (and spends the money) but leaves other things equal. This tends to raise interest rates and/or make it more difficult for private sector would be borrowers to borrow.”

I’m still climbing the steep part of the “MMT Learning Curve” Ralph and find that statement confusing in that it seems, if I recall, to contradict what Bill has been saying.

I think Bill said that as the private banking sector is not constrained by reserves in its lending, then, it follows that government borrowing to “fund” the structural deficit cannot lead to “crowding out”

Randall Wray seems equivocal too on the subject (in Understanding Modern Money), even referring to the possibility, in a footnote, of “crowding in”.

Am I missing something here ?

Dear Bill,

Even Greek politicians are questioning their policies. As a senior politician was telling me today he wished he had listened to me 6 months ago! Now he things inevitable some sort of restructuring! Returning to the drachma is still out of the question.

Regarding LT rates……I am tired talking about it. The CB is the monoply issuer and market maker of reserves and not the issuer or market maker of secondary transactions of LT securities. So it is better to stick what it can control best and not try to use one instrument reserves to control the whole structure of interest rates that results in an indeterminate solution, unless it is prepared to corner the whole LT market, Then why issue LT bonds or any bonds in the first place?

Why is returning to the drachma out of the question? Is it for psychological reasons, or were legitimate reasons provided?

P.S. Absolutely agree regarding L.T. rates. Here you see the same resistance to data and logic that I encounter when arguing that loans create deposits with more mainstream types. There really is something strange about this profession.

“Crowding out” occurs when government competes in a fixed environment such as exists under convertibility. It does not apply when there is a $-4-$ debt offset for deficits in a fiat regime because at the macro level government “borrows” what it spends. But even that is not correct. There is no borrowing on the sense that it occurs in nongovernment. When government issues debt as an offset, it just transfers the funds created by spending from deposits to tsys. This is just a shift in asset composition. Moreover, debt issuance further increases net financial assets of nongovernment through the interest paid.

“Crowding in” refers to creating a stable environment for investment. Investors do not like uncertainty. Therefore, government policy that creates stability is good for investment. Wray credits Keynes for this here (3rd para).

It would be interested to know from Stephan or some of the other German-speaking commentators here how the German media is reacting to Krugman’s calls for more deficit spending. He has been on a pro-deficit/anti-austerity rampage recently, specifically targeting Germany and the U.S., but other nations as well.

Panayotis/RSJ,

It is incredible that even after historical evidence about the Treasury and the Fed pegging rates at different points in time, you seem to not see the point. The point is not whether it is done right now – the point is it can be done.

Countries even peg their currencies, though in that case they can run out of foreign reserves. Here there is no risk.

I am amazed at the resistance to this point – ceilings can be put with a mere announcement. The markets will automatically gravitate toward that rate. If you do not think so I will be happy to have you as a counterparty and buy Treasuries from you and sell it to the Fed.

Secondly, you tend to think of the Fed spending billions in OMOs. On the other hand, the Fed regularly makes profits out of these operations!

I suggest you read how they set the overnight rates in Canada – because the Bank of Canada seems to know how to do this better than others.

When the central bank makes a rate annoucement, people tend to think that the central bank is buying or selling zillions of dollars or something like that. In reality, nothing of that sort happens. Banks automatically move to that rate.

Ramanan,

right.

Anon,

I remember reading a speech by Ben Bernanke in which he said a few things about the interest paid on reserves. According to him, some of the institutions which are allowed to participate in the Fed Funds market were not getting paid an interest on reserves and they were lending below the target rate. However, he also said that some member banks were simply lending at a rate below the interest rate paid on their reserves because they didn’t know the new rules. I am sure the traders must have been given a bad time by their managers – even though the managers wouldn’t have known these things correctly.

The Bank of Canada seems to have educated the banks and the rate targeting/setting is a cooperative operation.

So if a central bank really wants to peg the yield curve, in addition to making an announcement, it may also need to educate the players. It can just release a one-pager saying “beware of counterparties buying it from you and selling it to us”. What do you think ?

Ramanan,

The whole argument that P. gave flew right over your head. Sad. You do understand the difference between short and long term rates, right? I mean, Anon does not — fine, but you should. So why give “evidence” for government control of long term rates by citing evidence of government control interbank rates? You do understand that the mechanisms are completely different, right? right?

And this is not the first time that you “rebutted” a discussion of long term rates by citing commercial paper or interbank rates. Strange. Again, there is something wrong with this profession, and you demonstrated it just now.

@RSJ 11:35

My view from across the border in Switzerland. Maybe Stephan can add more details from within Germany.

Krugman isn’t very prominent here, yet. He does appear occasionally in more left-wing media and I saw a preview for a documentary portrait of him the other day. But apart from that, most media reports on economic matters and public discourse are within the dominant, ordo-liberal paradigm. The occasional insight, that maybe, just maybe the austerity will have the opposite effect of what it wants to achieve is never followed up by any discussion about why this might be so. The only opposition is from those whose benefits are going be cut (the CDU/FDP are behind in polls for the first time since quite a while) – but that is more reactionary than intellectual. Germany is the economic elephant in the Euro area and it has achieved this status by following its own neo-liberal rules more strictly than others. They’re a role model. Why question them? The southern European countries on the other hand that had much looser fiscal arrangements (and weaker currencies) before the EMU, are precisely what the Germans tried to avoid when (co-)designing the Euro parameters. So the Euro is what they wanted and it’s what they got / are stuck with and -more importantly – are still too proud to question.

It also seems to me that Europeans have not connected the dots between anaemic growth, constant high unemployment and their economic foundations yet. They still see themselves as the better version of the US (which of course we are :-D). And the traditionally strong stabilisers do alleviate some of the hardship better than the minimalist US social net. Continental Europe is slower, overall which has some pros next to many cons.

RSJ,

Not the first time! Unfortunately such commenting doesn’t help. Anger during a debate shows a weaker position.

Please read Michael Woodford where he gives the details of how the Fed and the Treasury put a ceiling on the 25y point during the World War. The reference is Fiscal Requirements for Price Stability

I wish I could use a mirror here so that whatever you told me goes back to you. Such a commenting doesn’t help. Bringing other comments do not help. When I was talking about commercial paper I was just giving an analogy about banking business versus direct borrowing, not short term versus long term.

To understand how the interbank markets – its a prerequisite to understanding long term yields. Else one can make all kinds of models based on vague arguments and that doesn’t make one different from neoclassical economics.

Here’s something from Michael Woodford’s paper. He is a New Keynesian but knows central banking well.

Accept that you are wrong and adamant 😉

Ramanan,

The glitch in fed funds target tracking has been due to two factors:

a) Some institutions (most importantly Fannie and Freddie) maintain balances at the Fed without being compensated

b) Others have been unwilling to take full advantage of the arbitrage opportunity presented in a), due to lingering capital and credit concerns in the US banking system

The Canadian system has tracked well because of the absence of both a) and b) factors. Canadian banks are in the best credit and capital shape in the world, and they are fully aware of this in dealing with each other.

The announcement effect works in the case of the existing policy short rate because of the implicit/explicit threat of mass force on the part of the central bank.

It could work throughout the curve if the central bank chose to threaten it in the same way. The balance sheet would be potentially massive, but this is not limited and would not interfere with interest rate control. (Mosler has noted this many times as you know).

I don’t know why you engage RSJ in such discussion. This commenter has little understanding of the monetary system and constructs inconsistent theory along the way like popcorn. You on the other hand have researched your subject impressively.

My two cents.

Krugman’s comment was noted but not prominently. I don’t think a lot of people know Krugman and those who do associate him with Keynes. And Herr Meier knows two things about Keynes: an unresponsible gay who advocates government debt. And as Krugman also learned by now the word “debt” in German (“Schulden”) has two meanings: “debt” and “guilt”. As such it has not only economic but also moral implications. And voila we’re at the core of the German political and economical discourse.

But the real problem are German economists. Keynes was right that ideas matter a lot and German mainstream economists demonstrate their flaws in thinking on a daily basis. Yesterday 4 prominent ones (Clemens Fuest, Martin Hellwig, Hans-Werner Sinn, Wolfgang Franz) published an appeal to the German government titled “10 rules to save the Euro”. Although they acknowledge (surprise!) that part of the problem is the pathological German fixation on export their cure is: an insolvency mechanism for sovereign members of the Eurozone.

And that’s exactly the problem. This insistence on an insolvency mechanism reveals their basic misunderstanding of a sovereign nation. They think a sovereign nation functions in the same way like a private enterprise. This logic is deeply flawed and renders their whole economics obsolet. A sovereign nation can not simply go out of business, it’s daily tasks go on beside any solvency problems. A sovereign nation has ongoing obligations which it can not simply delegate to another entity.

So basically I think the economic woes of Europe are only the effect of some deeper problem. Somehow in the whole frenzy about EU and Euro the philosophical concept of what constitutes a sovereign nation got lost. And I see only two ways out: either we go back to single sovereign nations within a freetrade zone or move on to a sovereign Federation of European States. Tough choices 😉

Some other thing. I read this week in a book “Volkswirtschaftliche Saldenmechanik” (Macroeconomic Balance Mechanic) by Wolfgang Stützel written in 1958. Which raised the heretic question in me what exactly is “Modern” about MMT 😉 It’s like reading Bill in German. In the introduction he writes, that there are some fundamental economic truism – the mathematical equivalent of 2+2=4 – which Stützel names “trivial-arithmetic-relationships”. For the fun of it I translated one of his fundamental theorems:

Partial Theorem: For each economic agent or group of agents more spending means a decrease in financial assets, more income means an increase in financial assets and vice versa.

Mechanics: Each economic agent (or group of agents) achieves (or suffers) only then and in exact the same extend a decrease in financial assets through increase of spending, if the complementary group achieves (or is willing to achieve) an increase of financial assets.

Global Theorem: The totality of economic agents (the economy) can never change its financial assets either through increase or decrease of spending or income.

Starting from here he goes on in his 2+2=4 manner and demonstrates nicely with trivial-arithmetic, that Angie Merkels savings aspirations are futile. Very funny. A Bill Mitchell on the beginning of the German economic wonderland.

“This insistence on an insolvency mechanism reveals their basic misunderstanding of a sovereign nation.”

I have to disagree. Their insistence reflects their basic desire to transform other areas of the globe to non-sovereign regions (what are nominally called “countries”).

Insolvency mechanisms are another word for bankruptcy – you must liquidate all your assets and your creditors “take” a haircut. Now, what assets does a country/region in this situation own and who are the debtors? The public finds out who is holding the bill, they look around and only see each other. Oh, you mean us – our pensions and social programs and public utilities, you want that? That is the price for EU membership? Let me go look at the membership agreement, oops too late.

This is why the ideology of “taxpayers pay for government spending” is so prevalent – it isn’t just what neo-liberals believe/understand, it is necessary to justify the ongoing expropriation of the public. In a non-sovereign region – their is NO SUCH THING as a taxpayer. Yes, their is a private individual/entity that must pay something named a tax to an official. I prefer to use the term “subject” – like the 15th century English subject who had to pay up or die.

I want to stop explaining/justifying this behavior as “misunderstanding”. They know EXACTLY what they are doing – there is nothing they don’t understand. They just aren’t stupid enough to announce their intentions.

Stephan:the word “debt” in German (“Schulden”) has two meanings: “debt” and “guilt”.

In the history of religion, the concept of sin is based on debt/guilt. Sin signifies a debt that must be satisfied by repentance/reparation or punishment. There is a strong historical force behind such concepts, and evolutionists would say that they have an evolutionary role in the development of the adaptive mechanism of the species. It also shows why such concepts are difficult to change. The neural programming runs deep in the societies that transmit such memes through cultural conventions and institutions. This is a dimension of the household-government finance analogy that goes way beyond economics and politics.

@pebird

OK. Never looked at this from your perspective. So there are two possible explanations:

(1) Economists have an ideological bias against government. This ideological bias transpires into economical stupidity which is reflected in the media as the wisdom of the day. It influences politicians and their decisions. Society subscribes to stupidity and validates it via elections.

(2) Economists have a thorough understanding of what is going on but have another self-serving agenda. Beside better knowledge they conspire against the public purpose. Politicians and media are too stupid to detect this conspiracy and the public validates it via elections.

Sorry but I tend to (1). I do not think that Sinn et al are evil per se. I think they look at the world through their ideological googles and see whatever gets through the ideological filter.

Stephan: “Which raised the heretic question in me what exactly is “Modern” about MMT ?”

I have always thought that “modern” modified “money” rather than “theory”, modern money being fiat currency. 🙂 (And “modern” meaning “post 1500”.) OC, fiat currency goes back centuries, but went out of use and was revived in the 1690s in the American colonies. 🙂

pebird: “I want to stop explaining/justifying this behavior as “misunderstanding”. They know EXACTLY what they are doing – there is nothing they don’t understand. They just aren’t stupid enough to announce their intentions.”

Hear, hear! 🙂

@Tom

100% d’accord. Some years ago I had a discussion with a friend working as a market maker at the Zurich stock exchange about money. I sent him Lerner’s “Money as a Creature of the State” paper from jstor. He was really shocked. No intrinsic value instead a government constructed fata morgana. Just valid IOU because of sovereign tax coercion. Strong tobacco. I’ve no idea how to change this public illusion about money, debt and credit.

Stephen:

Of course, Sinn and others are not evil. They do work for someone or have clients to support their self-employment, and whoever is buying/hiring them must want what they produce. Sinn is a symptom, not the problem. Also, I don’t mean to imply that evil is a good explanation – there are other forces – but let’s not forget these are very, very smart people.

I am more interested in the buyers of this “mis-information” than the mouthpieces themselves. I think that the Senn, etc., often function as a first line of defense to slow the rest of us down with twisted logic, absurd assumptions, simplifications and bad mathematics. Does it matter whether they have an ideological bias against government? I mean, so do I to some extent. But I have no bias against the notion of a public (that’s a subject for a different discussion).

I also think the media is virtually disconnected from what these experts say – occasionally they bring on an “expert”, but from the public’s perspective the guy is a talking head – his authority lies not in his reputation but from the very fact he is on TV and has some nominal title. If the public would accept a monkey saying the same thing (“government is bad, where’s my banana”), they would put a monkey on TV – its probably cheaper. Oh wait, over there is Glenn Beck.

Stephen, I actually agree with 99% of your original comment – any anger transmitted here I did not intend to direct at you or your comment, and maybe I parse words too closely, but I am tiring of so-called experts and find their work to be non-value added (maybe value-subtracted is more accurate).

I would prefer to figure out a way to push them aside.

Ramanan,

I said “not for the first time” because our socratic dialogue tends to run in the following circles:

First, you say “The Government can control the yield curve at all maturities” — that is a mantra, without which you don’t get to wear the MMT button. Like Walmart employees, this chant must be repeated every morning.

Then I point out all the failed attempts to control long term rates — over a trillion in POMOs spent on trying to drive down mortgage rates, for example, interbank rates can be controlled with the addition or removal of just a few billion, which is itself quickly reversed. How can the two rates behave so differently? Could it be that they have different elasticities? Could it be that arbitrage is possible in one of them but not the other?

But this is met by a response at how effective the government is at controlling interbank rates — where it both lends as well as borrows. In the interbank market, the CB both is the marginal buyer and seller — which is what you need when the good can be re-sold.

Then, I agree that the government can (and must!) set the marginal cost of reserves, but that this does not translate into control of long term rates, because in that market, the government is not willing to lend, but only to borrow. If it was willing to offer anyone a mortgage at a rate of 2%, then clearly mortgage rates would instantly fall to 2%, and the government would have the same control of the mortgage market as they do in the interbank market. Same thing for funding business expansion. But as long as the CB only lends to banks — and with strings attached in the form of capital requirements that make it unprofitable for banks to fund anything other than real estate — then control of interbank rates will not propagate to control of long term rates.

Then, after getting some form of agreement that longer term rates are not the expected future interbank rates, the debate shifts and you say that there are two yield curves in the bond market — the “private” yield curve, and the “government” yield curve, and the government, buy buying up all government obligations, will control the government yield curve, but not the private sector one.

And then to this I respond that first, by removing an asset from the market place, you are not controlling its price. Second, all assets compete — why would these yields permanently diverge? Control of one is control of the other. Why would an arbitrageur not short the more expensive instrument and buy the cheaper one?

And at this point, the conversation stops.

The next morning, we start all over again “The Government can control the yield curve at all maturities!”.

It is like Groundhog’s day. Seriously, this is a zone of illogic — much like the belief that government bonds are a “savings account” at the CB, or that low interest rates — or the lack of payment of interest on government debt — is “deflationary” because of the “loss of interest income”.

In terms of the Fed accord — you might enjoy reading the documents at the Richmond Fed’s portal on the Treasury Accord. Basically the issue here is that during the war, we were on a command economy. Prices, labor, and interest rates, as well as capital investment, the monetary aggregates, the quantity of loans that could be issued — was government controlled. I never argued that in a command economy, the government cannot set prices.

The problem was in the dismantling of that command economy after world war 2. The U.S. wanted to continue to have low long term interest rates while simultaneously moving away from control of the monetary aggregates. Obviously people began to engage in the process of capital arbitrage that would normally lift these rates — remember the golden rule — and this set off an enormous investment boom that led to 20% price inflation — the highest inflation since WW1, and the highest peacetime inflation we’ve ever had. The CB was in effect conducting fiscal policy, by subsidizing investment. The spread between the price it was willing to pay for the security and the return that the investor could get from the proceeds of the sale was a fiscal gift to the investor. And one of the main reasons for the accord was that

Whenever the CB knowingly overpays for an asset, it is conducting fiscal, not monetary policy — and this requires congressional authorization. The fact that the Executive branch didn’t have a legal leg to stand on here was one of the reasons why Eisenhower agreed to the accord — that and the 20% price inflation.

So yes, the government can buy up all long term assets for any premium it is willing to pay above the market price — agreed. But that does not mean that it can set the price of long term interest rates, which are subject to capital arbitrage and are therefore endogenous.

Now I direct these arguments at you because people like Woodford — in addition to being stuck in the neo-classical morass of stock-flow inconsistent models — are unable to distinguish between interbank rates and credit market rates. For one reason or another, they build their models on the assumption that investors can actually borrow money overnight from the CB at the FF rate, and receive money overnight at the FF rate. Woodford has zero scope of capital requirements and balance sheet requirements in his model, nor does he take into account the different risk-weights that banks must apply to their mortgage and business loan assets. In his models, the CB directly loans in unlimited amounts and without collateral requirements to any investor at the overnight rate.

In that case, he would be right that longer term interest rates would be the expected value of future short term rates. But that model, as the rest of his monetary policy models — is hopelessly flawed. It is also an exogenous capital model. But you, as a heterodox, at least know about capital arbitrage, actual constraints on banks, and so should not be parroting NK monetarism.

@pebirrd

No problem!!! I didn’t conceive your anger directed at me personal. Any ventilation in this regard is always welcome. But now I disagree. Sinn is not a symptom he’s definitely the source of dis-information. These people command a lot of respect! To possess an aura of authority means a lot in any German discourse. A German Glenn Beck won’t happen for the next 1000 years 😉

That said I’ve changed my mind about Glenn. His show about Hayek was brilliant! He moved with a single hand “The road to serfdom” to #1 on Amazon.com. Not bad for an illiterate public audience addicted to cable TV trivialities. I myself consider Hayek #8 or #9 of the most influential economists of the 20th century (my private hit list 😉

I wish we would have such a great communicator for let’s say Keynes on our side. But we have only wishy-washy progressives with caveat statements like “debt is bad but …” and “of course we must do something about the deficits but …” We’re the “they’re right but …” party.

The above should replace Eisenhower with Truman — Eisenhower was much more reasonable 🙂

RSJ,

I suggest the following exercise – take a piece of paper and write down T-accounts in which the central bank does some transaction, government does some transaction and when banks do some transaction. Start from scratch and forget about complications such as capital requirements etc. If you like I can suggest you some articles. Don’t get the data and plot some graphs – just some T-accounts. In the next exercise, ignore banks and try to work out some transactions which do not involve the banking sector. Figure out that it is impossible. Then go back to the first step and ask what happen when the government spends . Write down the T-accounts. Find out what happens when taxes are paid.

Then do some transactions to figure out how a bank makes a loan. What happens if deposits move out ? What happens when the bank finds itself needing some funds. Why does it need some funds ? Do banks have accounts at each other? How do they settle ? What are the interbank liabilities ?

Then do some transactions involving the government sector. How do T-accounts look when a government issues debt? What happens to reserves when the government issues debt? What does a central bank do when the transactions involving bond issuances happen ?

Then ask more complicated questions – how do firms pay their employees? Issuing equities? What are the other sources of income for sectors such as the households ? When a government pays coupons to the bond-holders, where does the money come from ? Then ask more complicated questions such as “how come the central banks make a profit?”, when your intuition is that they throw money to the bankers.

Then bring in your favourite – equities and corporate bonds. What are the transactions which involve purchases of these ? Do banks enter in the transactions or are irrelevant ?

Then ask yourself more financial markets questions such as “what exactly is an arbitrage”. “How does one short a Treasury?” “Are there people out there who short Treasuries everyday and go long corporate bonds”. “what are the risks involved?” “What are yield curve trades?” “What is a steepener trade?” “How does one bet on the yield curve?”. “Why do yield curve trades lose money sometimes?”. “What are the constraints on the yield curve?” “Can the traders and portfolio managers predict the growth rate of an economy for the next 5 years?”

Then imagine yourself to be the CFO of a non-financial firm. Ask why you will need working capital. Will you need a relationship with a bank or succeed by just issuing equities ? When the revenues flow, what are the transactions that happen? Do they involve a bank ? How do you decide what to issue – equities or debt ? How do you decide the maturity ? Do you just ignore the banks ? Will you make decisions on stock buybacks or is it irrelevant ? How do you finance a stock repurchase ? How do you hand out dividends ? Do you have a gang of economists who are predicting the growth rates of the United States of America and do you think they will consistently give you the right answer ?

I do not know what Woodford does, but there are more things you can think of.

How do banks decide on the loan rates ? Does it change by some divine phenomenon ? Does anyone in the blogs you visit assume that the loan rates is equal to the FF rate ?

Ramanan,

I absolutely agree that these are the types of questions to ask (and answer) — but my advice to you would be to not start from the CB and go out, but to start from a model of production and then work towards an understanding of how that production is financed. The two are not independent! Then bring in the CB, etc. I think if you do this, you will find the process enlightening — at least it was for me! MMT is too banker-centric, as a cultural phenomena, and it colors many of the conclusions, as I’ve pointed out in other posts. In the same way, I think mainstream macro-economics is too price and market centric, with production being an afterthought.

If you want to know more details about this — I would check out reading some of texts at The Other Cannon, which also features some texts by authors in kinship with MMT, such as Michael Hudson, who also did a guest appearance on Steve Keen’s site, IIRC.

But feel free to share any new insights from your intellectual journey — in particular, how they lead you to believe that the government can control the yield curve to any maturity without simultaneously destroying the credit markets.

As far as Woodword is concerned, he is the main instigator of Central Bank taylor-rule reaction functions, as he provided a theoretical framework for the use of CB reaction functions in controlling inflation and output. Woodford, much more than Taylor, is largely responsible for the current CB economic management paradigm, in which overnight rates magically propagate and determine the nominal rate of interest, whereas the real rate of interest is set by the economy. In this way, the CB controls inflation. I would definitely recommend reading the 2003 book — which is an easy read — and becoming familiar with these types of models, if only to know what you are up against and to better understand the assumptions on the orthodox side. To his credit, he does have some good stability results, so the book is worth reading as just a modeling exercise.

And to clarify the disagreement between us a bit further, when I say “start with a model of production”, I mean that the process of production is complex, non-linear and constrains the mechanisms that finance production. What you see in the sectoral balance sheet models are fairly trivial production models — simpler even than the Cobb-Douglass production models used in standard models.

Profits eventually diminish with further investment, new forms of capital are continually discovered, but at varying rates (e.g. the internet boom bears much resemblance to the railroad boom). Overlapping commitments create an inertia to the cost of capital that new entrants must meet. There are falling unit costs and increasing returns for goods producing firms, meaning that there must be downward sloping demand curves for these products. Simultaneous to that, the bulk of our purchases is for services, which do not have increasing returns to scale. This means you do not see reverse L-shaped inflation curves that are a function of excess capacity, as excess capacity is inapplicable to the bulk of consumer spending.

Moreover, 2/3 of sales in the economy are from one business to another that are driven by long term contracts, meaning that a rapid increase in stimulus spending is going to affect the business sector differently from final output. Likewise lowering bank costs are going to affect land prices differently than the cost of business funding.

All of this is ignored when your analysis starts with exogenous transaction flows (e.g. from G-T) and assumes that these determine real output via fixed constants.

So it is not a question of either/or — you can have both! A serious attempt to model production within the context of a stock-flow consistent model. But the price that you pay is that many factors — in particular interest rates — that were completely exogenous when you trivialize production become endogenous when you take it seriously. Once you do that, arguing that interest rates can be set to whatever you think is “fair” becomes problematic.

So in addition to counting the money flows properly, you need to consider what drives the money flows — the bulk of them are driven endogenously by the household and firm’s assessment of changing profit opportunities, and these actors can neutralize or even overwhelm the naive views that interest rates determine the profit rate, rather than vice-versa — or that a lowering of interest rates leads to an increase in wage shares.

When the cost of capital is lower than the return, the profits result in excess income to the owners of capital, not excess income to workers. Although in general — the cost of capital will average out to be equal to the return in competitive markets. I believe this is why capital’s share in the U.S. has been so constant despite a massive attack on labor’s bargaining power, whereas capital’s share in other economies with less developed capital markets has been increasing. In China — the poster boy for capital market manipulation and repression — capital’s share is now close to 2/3 of GDP, having doubled since 1980.

So you need to start with an endogenous model of production and consumption, and then add accurate money flows, and then add a central bank and financial system. If you do this, you will often get completely different conclusions than the models with fixed savings ratios, fixed productivity ratios, reverse L-shaped inflation models, and no concept of utility maximization or arbitrage.

It is hard work, and easily subject to criticism — not at all as clean and easy as simple transaction models in which you take as axiomatic constants all the important and complex factors. But it is real economics — and this is what the heterodox people need to do in order to get credibility.

RSJ,

There are works done on production as well and you just have to look – which you may want to instead of coming with your own bias. In case you want to look at the non-monetary side of Post Keynesian Economics, I suggest you read Marc Lavoie’s “Introduction to Post Keynesian Economics” – its a short and nice read and will provide you ideas about labour, capacity utlization, unit costs behaviour, price setting, costing margin, employment, history of PKE, references and the various production aspects of economics.

I am not an economist but really like this stuff even the production models. In fact, you can see from these models why the monetary system is build the way it is and how various “circuits” are acts of production rather than some repurchase agreements.

The reason you see a lot of banking related stuff coming is the fact that the monetary aspects are really important. The economic theories which do not consider monetary aspects land into trouble precisely due to that reason and inherently there is some monetarist assumption that is made or perfect foresight assumed.

The fact that monetary aspects are stressed in the blogs you visit are because the interests of the hosts is in the monetary aspects and how the monetary system behaves effectively rules out all the non-heterodox models that are out there.

Dear Ralph (18/6/10 at 16:20)

You said:

There is no financial crowding out involved in governments issuing debt. All they are doing is draining reserves even if that is hidden by all the elaborate institutional machinery that they have erected to make it look as though they are borrowing. It is a wash. They spend and add to reserves and they borrow and drain them.

best wishes

bill

Dear Neil (at 2010/06/18 at 18:24)

QE is silly because it doesn’t do what the central banks think it does. They think it provides banks with increased capacity to lend by adding extra reserves.

The banks don’t need the extra reserves to lend. They need credit-worthy borrowers.

best wishes

bill

Dear John Armour (at 2010/06/19 at 8:39)

Not a thing.

best wishes

bill

Dear Panayotis (at 2010/06/19 at 9:53)

I agree. I have never said they should control the whole structure of rates. But the central bank can clearly set the short-term rate or the 10-year rate if it chooses. So if the government insists on issuing debt let it issue short-term treasuries and the yields will be set my the liquidity operations of the central bank. Simple.

I don’t advocate that. But it demonstrates, ultimately, who is in charge. I am sick of people thinking the bond markets run the world.

best wishes

bill

Dear RSJ (at 2010/06/19 at 10:33)

Please see my reply to Panayotis. There is no head in the sand going on here. The central bank can do what it likes. That is a different thing to advocating the same.

best wishes

bill

Dear anon, RSJ, Ramanan and all

Remember to keep the commentary and the debate above the level of personal invective. We all know a few things and like to share that knowledge. If we are wrong we can admit that and we will be better for it.

But keep the debate fierce but decent.

best wishes

bill

Ramanan,

G&L have a simple linear transformation model of production. Things like unit labor costs and markup pricing are not a production model, but a determining of factor prices. The conflation of these with a production model is telling. Pierro Sraffa had a production function, but it was also linear, although in his case, to his credit, he used linear algebra (e.g. functions linear in each variable, and therefore reducible to matrix multiplication). Joan Robinson worked with nonlinear production models, but in a simple one good economy, and the analysis was limited to curve drawing in her “accumulation of capital”. I think part of this is due to the Cambridge Capital Controversy — PK’ers seem to have decided that production was just determined by simple political decisions, or that it was too complicated to model, and so they turned away from this problem. Perhaps some did not, but G/L certainly ignored it.

Over the long run, it is the production model that determines prices, markups, and interest rates. Over the short run, exogenous financial flows can drive things. But you cannot go from a linearization applicable to short run time frames to a model that uses fixed constants to convert financial flows to real goods flows over the long run, or as a motivation for serious policy changes. That is putting the cart before the horse, so to speak, and making the financial flows the king of the real flows. In reality, the financial flows are subservient and secondary to the real goods flows. That is the criticism about being too bank-centric.

So I would say that both the PK — at least that subsection of PK models with which I am familiar — as well as the orthodox models are deeply flawed.

You are right in criticizing the lack of stock-flow consistency in the orthodox models, but it seems that you don’t see the equally valid criticisms of the orthodox group directed at the flow of funds models. Specifically the map from the financial flows to the real flows is trivial. That is why you see such simplistic notions of the causes of inflation — e.g. Mosler’s view that it is just oil prices, completely controlled by Saudi Arabia. Or other views that there is a reverse L-shaped curve so that additional demand has zero affect on inflation up until some magical point is reached, at which point it is *all* inflationary.

And it is only because there is no “real” production model in the model that you can believe that the exogenous financial flows are more important than the real characteristics of production, and that these flows drive the production characteristics over the long run.

Ideally, you want a theory that incorporates both, and G/L does not do this — neither does Keen, with his models. And this is why you see Scott Sumner echoing the mainstream view that PK’ers have no model of prices. The response is — well, we have supply and demand functions! But these functions are obtained by multiplying or dividing the exogenous flows by fixed constants, and so the mainstream will not take them seriously.

And they should not.

My criteria for a legitimate model would be one that could explain, for example:

* How did China drive the consumption share of GDP from 2/3 to 1/3 while maintaining negative or very low real rates?

* Why has the labor factor share in the U.S. been constant?

* Why does the private sector suffer demand failures, and how many assets should the government sector supply them with?

* Would a zero FF rate, combined with a requirement that banks only hold loan assets, be inflationary or deflationary, and by how much?

* What would a doubling of oil prices do to employment, prices and output over the near and long term?

* What is the relationship between inequality and bank cost of funds? Between the latter and real estate prices? Between real estate prices and productive investment?

* Why do unit labor costs tend move in the same direction as nominal interest rates?

* Why have markup costs moved in the opposite direction as nominal interest rates in most of the developed world, but have moved in the same direction as nominal interest rates as Japan?

* When will the private sector in Japan have “enough” savings and what should the long run budget deficit of Japan be?

You should be able to write down a fairly simple model that includes both production as well as financial flows — e.g. that combines “real” and monetary effects, that is able to provide answers to these questions. It doesn’t matter what these answers are, but as long as the model can provide answers, then it is at least able to capture the interchange between changing production characteristics and changing financial flows. Then the model is a candidate for serious consideration.