In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Bank of England official blows the cover on mainstream macroeconomics

It is quite amusing really watching the way orthodox economists who know the game is up work like gymnasts to avoid actually spelling out directly what the facts are but spill the beans anyway. Last week (April 23, 2020), an ‘external member’ of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, one – Gertjan Vlieghe – gave a speech – Monetary policy and the Bank of England’s balance sheet. If the message was taken seriously, then the way monetary economics and macroeconomics is taught in our universities should change dramatically. At present, there is only one textbook that seriously caters for the message that is inherent in the speech – Macroeconomics (Mitchell, Wray and Watts). The speech leaves out important insights but essentially allows the reader to appreciate what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has been on about, in part, for 25 years.

Background reading

Here are some past blog posts I have written on this topic. You will not find anything that the Bank of England official said in his speech that wasn’t covered in these blog posts (among many others).

That is especially the case with the earlier posts – written in 2009, for example.

One wonders why it takes more than a decade for officials in central banks to tell the public what is actually going on rather than what the defunct macroeconomists have led everyone to believe.

The point is that revealing these things is an important step in allowing the public to understand better policy choices – and see, clearly, why, in the current climate, any talk of going back to austerity to ‘pay’ for the coronavirus stimulus packages is nonsensical and damaging.

1. Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 (February 21, 2009).

2. Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 (February 23, 2009).

3. Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 (March 2, 2009).

4. Quantitative easing 101 (March 13, 2009).

5. Will we really pay higher interest rates? April 8th, 2009 (April 8, 2009).

6. Will we really pay higher interest rates? April 8th, 2009 (April 21, 2009).

7. The impact of government on reserve dynamics …/a> (August 19, 2009),

8. Operational design arising from modern monetary theory (September 20, 2009).

9. Building bank reserves will not expand credit (December 13, 2009).

10. Building bank reserves is not inflationary (December 14, 2009).

11. On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose (December 25, 2009).

12. The consolidated government – treasury and central bank (August 20, 2010).

13. The role of bank deposits in Modern Monetary Theory (May 26, 2011).

14. New central bank initiative shows governments are not financially constrained (January 24, 2012).

15. The ECB cannot go broke – get over it (May 11, 2012).

16. The sham of central bank independence (December 23, 2014).

17. Bank of England finally catches on – mainstream monetary theory is erroneous (June 1, 2015).

18. On money printing and bond issuance – Part 1 (August 26, 2019).

19. On money printing and bond issuance – Part 2 (August 27, 2019).

20. When old central bankers know what is wrong but can’t bring themselves to saying what is right (October 8, 2019).

The important parts of the Bank of England official’s speech

In terms of the UK government’s response to the coronavirus, we read that:

Fiscal policy is best placed to target the most affected sectors, and the government has rapidly launched a wide range of programmes to help both firms and households who have been directly affected.

Which is why, in part, we advocate the primacy of fiscal policy interventions.

Monetary policy changes are uncertain in impact, cannot be spatially or cohort-targetted, and may fuel asset price bubbles. It is clear they cannot prevent recession in the same way as direct fiscal stimulus can always do if there is sufficient political will.

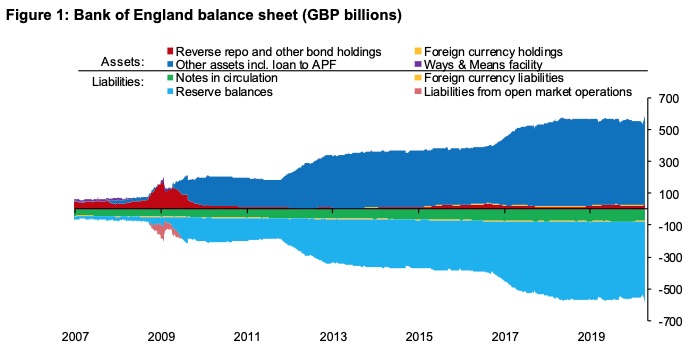

He presented this graph which shows that since the GFC, the Bank of England has been swapping bank reserves (light below) for its holdings of government bonds, which it has been buying in the secondary bond market.

This balance sheet pattern is repeated across many central banks now as they have been effectively ‘funding’ government deficits through their various public bond purchasing policies. They have been saying one thing (that they are not doing that) while doing exactly that.

The Speech recognises that:

By definition, only the central bank can provide central bank deposit accounts. So only the central bank can provide reserves.

He talks about “purchasing government bonds financed by ‘printing’ reserves” and qualifies that statement with:

I using … (sic) … “printing” figuratively here as the transaction is entirely electronic. I use it here simply because many commentators use this terminology to refer to this type of transaction.

So he is not challenging the ‘framing’ and the ‘language’ of the conceptualisation of reserves being swapped for bonds – an entirely digital transaction – as being ‘monetary printing’ despite the ideological baggage that that last term carries.

He knows that the “many commentators” who use this sort of terminology actually misuse it deliberately to evoke emotional memories of wheelbarrows and crazed central bankers in basements running printing presses.

That, in turn, is then used as a scare campaign to continue to issue corporate welfare in the form of government debt to the non-government sector to match deficits, when it would be much simpler and involve less costly administrative machinery for the treasury to just instruct its central bank to credit bank accounts to facilitate government spending (as it does now) without matching deficits with bond-issuance.

The Bank of England official then describes how reserve maintenance (liquidity management) is used to maintain short-term interest rates at the levels the central bank desires.

He then talks about QE:

1. “the central bank purchases government bonds, financed by issuing reserves” – “involves the same basic balance sheet transaction as conventional monetary policy: buy government bonds, sell (or create …) reserves. It is just on a larger scale.”

2. “The central bank is no longer trying to balance reserve supply with the reserve demand from the banks” – in other words, the QE program creates excess reserves as a deliberate consequence. He calls the ‘excess’ “ample reserves” – gymnastics.

3. And, “The fact that central banks pay interest on reserves (IOR) is very important. If reserves did not earn interest, then the supply by central banks of ample reserves beyond what banks need at any given level of interest rates, would push the short- term interest rate to zero …”

This is core MMT but students in monetary economics do not learn about these dynamics typically.

4. Paying a support rate on excess reserves, means that “the macroeconomic impact of ample reserves is probably quite small” – so QE is ineffective.

5. Now it gets interesting:

This willingness by banks to hold even quite large amounts of reserves is crucial. It means that the (old) textbook idea that there is some mechanical link between reserves, broad monetary conditions and inflation is just not right.

He then cites two research papers – one from 2014 (a Bank of England paper) and one from 2019 (an unpublished LSE paper).

But, of course, MMT economists have been writing about this for 25 years. No other monetary or macroeconomist was writing about this and they still teach the money multipier as core pedagogy.

The world is catching up with MMT – but slowly and without recognition.

But abandoning the monetary multiplier is an extremely significant step along the way to ditching the main elements of mainstream macroeconomics.

It means that:

1. All the hoopla about expanding bank resereves causing inflation through money supply expansion is inapplicable.

2. All the claims about crowding out, which is a principle argument against the use of fiscal deficits, is inapplicable.

3. The whole mainstream conception of the banking system and its interface with the real economy, is inapplicable.

Move on!

He does move on to talk about the “Ways and Means” account that the Bank of England keeps for H.M. Treasury.

You will recall that on April 9, 2020, this announcement from the British Treasury was released – HM Treasury and Bank of England announce temporary extension of the Ways and Means facility.

Cover blown is what it told the British people.

Effectively, the ‘Ways and Means’ account is an overdraft that the Treasury has with its central bank that allows it to spend freely without satisfying the usual accounting and administrative practices (ex post) relating to bond issuance.

The announcement on April 9 said that the Bank of England would increase the available funds in that overdraft account if the Treasury needed to spend large sums quickly.

The language was all “temporary and short-term” and that the “government will continue to use the markets as its primary source of financing, and its response to Covid-19 will be fully funded by additional borrowing through normal debt management operations” but the reality was obvious.

They can increase fiscal deficits without recourse to the markets ‘matching’ the deficits with debt-issuance any time they like.

So what does the Bank of England official say about this?

He wants readers to confine their understanding of the Ways and Means account as a “short-term cash management tool”:

Rather than the central bank buying bonds, the central bank can lend directly to the government. If you think of a government bond as fundamentally a loan to the government, you can see that, mechanically, it is really just a very similar transaction again as QE and conventional monetary policy: government liabilities on the left, reserves on the right … The main difference from QE is that the initiative of drawing down (and repaying) the facility lies with the government, not the Bank Executive or the MPC.

So he is really saying that QE bond programs amount to the central bank providing ‘funding’ support for government deficits indirectly rather than through the primary debt-issuance process.

And allowing the Treasury to draw down funds in the Ways and Means account is a more direct but equivalent transaction.

We should note, of course, that government spending occurs in the same way, however, these administrative, institutional and accounting conventions and practices are exercises.

The Treasury instructs the central bank to credit bank accounts in the non-government sector on its behalf.

Every hour of every day.

That is how spending occurs.

All these other administrative type conventions do not alter that fact.

Further, what he doesn’t say about QE is that it provides instant capital gains to government bond holders. So, for example, primary dealers bid for the government bonds in the primary auction. They know they will then be able to offload them to the Bank of England ‘next day’ at a higher price than they purchased the debt for.

So just debiting a Ways and Means account and crediting some account of a procurement supplier is quite different to going through the whole hoopla of conducting primary bond auctions and then purchasing the bonds in the secondary market.

And now the ideology part:

The reason the W&M facility is not generally used is that the DMO seeks to use the market for its financing and cash management needs.

The DMO is the British Government’s – Debt Management Office – which was created in 1998 as part of the sham that pretended the Bank of England was now independent of government. It is just a branch of Treasury.

Prior to that, the Bank of England used to conduct all the debt operations on behalf of the government and often participated directly in the primary issuance process.

Many governments deployed the same tactic as an ideologically-motivated decision to promote the pecuniary interests of bond markets and to make it politically more difficult for governments to issue debt.

They knew that if the government had to match their deficit spending with bond-issuance, the debt ratio would become a central topic of conversation and that would limit deficits.

This was one of the legacies that the disastrous Blair Labour government left Britain. A smokescreen to limit government policy that might help the workers and the disadvantaged!

The Ways and Means process survived, however, to smooth out “government cash flows” – as a back up.

He says:

Such a back-up is rarely needed except in periods of sharp unexpected deviations from the financing plan.

That is, when the government knows it needs the Bank to credit bank accounts fast and hasn’t time to go through the ‘smoke and mirrors’ process of issuing debt.

More gymnastics:

The important consideration here, as far as monetary policy is concerned, is that due to the short term nature of these W&M cash management transactions, they do not in any way affect the MPC’s ability of doing its job of meeting the inflation target.

And, they would not affect the policy process if they were not short-term.

Then we move on to the real issue – “Monetary Financing?”

More ‘smoke and mirrors’:

We say we are not doing monetary financing according to our definition21, and someone else says we are in fact doing monetary financing according to a different definition. That is an argument about definitions, rather than about what we are doing.

The Governor of the Bank of England had told the Financial Times on April 5, 2020 – when the Ways and Means announcement was made – that monetary financing involves:

… a permanent expansion of the central bank balance sheet with the aim of funding the government …

What is permanent?

Who can know the aim?

They have been buying up government debt on and off for years now – see the graph above – is that not ‘permament’.

Central banks around the world continue to talk of ‘normalising’ their balance sheets (that is, getting rid of all the debt they have purchased from governemnts) but realise that the process is fraught in terms of asset values in the non-government sector.

Are their holdings not permanent?

They could easily just type some zeros into their accounts and write off all the debt. But they still would have been ‘funding’ the deficits.

Smoke and mirrors!

But we learn more:

One rather mechanical definition is that monetary financing means financing fiscal spending with central bank money rather than by issuing government bonds. The problem is … this description fits most central bank monetary policy operations, in the UK and elsewhere. When a central bank issues reserves, the main counterpart asset on the central bank balance sheet is generally some form of government financing.

Sure enough!

Cover blown 2.0

But clinging to the ‘mainstream’ life rafts he says:

… even though in a strict sense some part of government spending is always financed with central bank money, it is not the same as saying that this part of government borrowing is costless.

Where are we up to – CB 3.0?

He explains:

1. Government issues debt and pays interest to the non-government debt holder.

2. Government doesn’t issue debt, central bank creates reserves and has to pay a support rate on excess reserves not drained from the non-government sector as in Option 1.

Doesn’t this mean that the ‘cost’ of the deficits is the interest on excess reserves?

Cost is a loaded term.

The true cost of a government spending program is the extra real resources that are consumed in the process of policy execution.

But using the term in his way, what he is really saying is that the Bank of England is forced to pay interest on excess reserves if it wants to maintain a non-zero policy rate.

Partially true.

Apart from allowing the policy rate to go to zero (the preferred MMT position), the central bank could issue its own ‘debt’ instrument to drain the reserves, which I do not recommend.

Then reality is presented:

Is it ok for the central bank to finance some, but not too much? How much is too much? Before the crisis, central bank money (notes and reserves) in the UK was about 12% of government debt. Now it is 26% of government debt. In Japan it is 42% of government debt. There is no clear threshold beyond which monetary financing is “too much”, as long as investors believe government finances are sustainable without resorting to inflation. And, given the low levels of government bond yields and break-even inflation rates in the UK, investors clearly do believe that government finances are sustainable without resorting to inflation.

And not to mention the ECB funding the whole Eurozone show at the moment.

And it doesn’t really matter what investors think. They are supplicants.

What matters is whether the deficits are proportional to the non-government spending gaps (different between income and spending) and that total spending doesn’t outpace the productive capacity of the economy.

The bond investors are irrelevant to that process.

He also pulls the rug out from the “short-term” is safe, “permanent” is dangerous myth:

Can we say that a temporary operation is fine, but a permanent one is not? That is problematic too. We carried out several rounds of QE operations after the financial crisis, expecting them to be unwound some years later as the economy improved sufficiently. But the economy did not improve sufficiently, the neutral rate of interest fell more persistently than we expected, with the result that the amount of gilts we own has so far not been reduced.

As I noted above.

And then, while teetering on the balance bar (that long wooden beam that gymnasts always look like they are about to fall off and hurt themselves) we get the trump card:

… Weimar Republic or Zimbabwe …

But, thankfully, he equivocates because, presumably, he doesn’t want to align with the crazies who think the government shouldn’t be taking steps to defend the economic interests of its citizens. There will always be an Austrian economist somewhere in the ‘bushes’.

The equivocation only goes so far though and fails to reveal an understanding of what actually happened in Weimar and Zimbabwe.

Conclusion

The teaching programs in monetary economics and macroeconomics should be radically altered in universities around the world.

Even central bank officials are now, effectively, providing the arguments for that recommendation.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Still waiting for one of these ideologues to explain why the expectation that the Central Bank may ‘sell back’ the QE bonds it is holding is any different from the expectation that the Treasury may issue new Bonds.

Add that to why would anybody borrow money when things are bad and stop borrowing money when things are good just because the Central Bank has moved base rates by 0.25%.

The myths to prop up the failing core beliefs are moving from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Yeah you are right Neil. It is pretty obvious that MMT describes the world better than that other crap they taught us. It is at the point where they kind of have to admit it now.

Thank you for this synopsis, Bill. It is most helpful and enlightening.

Given these mechanisms have been exploited for some years, one wonders what else has been deliberately obscured by government. I’m beginning to appreciate just how essential the off-shore banking system is to HMG’s operations – what a fine place to conceal and channel dark money.

I suspect forensic accountants could be kept busy for years examining old spending programs….no wonder old Blighty can “punch well above her weight”!!

“This willingness by banks to hold even quite large amounts of reserves is crucial. It means that the (old) textbook idea that there is some mechanical link between reserves, broad monetary conditions and inflation is just not right.”

Mike Norman and Matt Franko have been saying for years now that due to the leverage ratio when the system is awash with reserves it makes it harder for commercial banks to give out loans. The excess reserves brings them near to the leverage ratio ( Basel 3) so in order to make more loans they have to raise more capital ?

Excellent analysis of that speech. I think the author has a Deutsche Bank backround so, presumably, will not want to blow the gaff on everything.

Bill’s gymnastics imagery is very apposite here. As one reads these reports/speeches. there is a feeling that you are about to experience something miraculous and the writer is going to reveal the whole show for what it is and then they use conventional framing at the last minute.

A good example of this is from Adam Tooze in the Guardian yesterday, similarly to Vlieghe, he desribes things as MMT might, challenging the Fallacy of Composition and yet refers to ‘sustainability’ in Debt/GDP terms making references to Tax as Revenue and not differentiating between the EU and US monetary systems (which Tooze clearly understands well). Not sure why they do this sort of thing-is it a fear of losing their tenure and academic status if they told the truth?

The Tooze article is hear (if Bill is happy to allow the link) and a good example of blowing the gaff while retaining the language frame of monetary myths: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/27/economy-recover-coronavirus-debt-austerity

With regard to: ‘Cover blown is what it told the British people.’

I don’t think the British People will be told much! The Tories are covering their spending with the usual myths about how austerity allowed us to spend now etc. The spending has also left a lot of people in the lurch, especially renters and maintained a cruel and punitive five week wait for Universal Credit while maintaining sanctions that deprive people of their benefits if applied before the pandemic. Still using the ill and vulnerable as scapegoats.

Treasury account balance over $1T

For the first time in history.

Matt Franko…

” If you see the TGA go up like this then it means reserves have been drained from the Depositories by that same amount.

It can go up due to the Treasury issuing more securities than it redeems or if the receipts are in excess of withdrawals or a combination.

Bottom line is a TGA increase removes or drains reserve assets from Depositories and acts to INCREASE the Depository system regulatory leverage ratio.

Banks can then perhaps increase loans or perhaps increase the asset prices of existing risk assets “

In short I suppose what Mike and Matt have been saying.

Reserves from a government point of view isn’t really an issue, but from a commercial bank point of view can cause real problems due to the regulations in place.

Derek, Matt is a little loose about his terminology and explanations if any. If he had a point to make he could write it out and explain it just like anyone else would do. A sentence here and there doesn’t cut it for me. Maybe he is right- but who could possibly tell from reading what he writes?

If you understand MMT you know the Fed is always, always going to make sure the payments system works and that includes the money banks create when they make loans. TGA, NSA, PGA- non of those initials impress me or change the facts.

Jerry,

They have to take the regulations into account. Jamie Dimon came out a fortnight ago

and said the exact same thing that Mike and Matt have been saying for years. Kinda

backs it up don’t you think ?

Don’t shoot the messenger – just ask him or Mike. Mike has done plenty of you tube

video’s on it.

Jerry,

Jamie Dimon came out a fortnight ago and said the exact same thing what Mike and Matt have been

Saying for years. That kinda backs them up don’t you think ?

Mike has done plenty of you tube videos on it. They have to follow the regulations.

Don’t shoot the messenger ask them.

There was, of course, an excellent Annex in the UK DMO’s “Revision to the DMO’s 2020-21 Financing Remit” published the other day.

It details the “Financing Arithmetic” for the year 2019/20 and it goes like this:

Net Financing Requirement (NFR) for the DMO: £161.9bn

Total financing: £143.6bn

DMO net cash position: £-17.9bn

Anybody asked them which sofa the DMO found the £17.9bn down the back of, if, as they claim, they are “funding” the government expenditure a-priori?

Derek, I’m never going to shoot anybody. I’m one of the many Americans that don’t have or want a gun.

Jamie Dimon runs an organization that the US Federal Government and their agent the US Fed kept from going bankrupt twelve years ago along with all the other similar banks. I have no doubt that he is a very intelligent man who understands MMT at this point. But what he says as a corporate mouth carries no weight as far as I am concerned.

When someone makes an argument that they want others to consider seriously- well they should do it in more than one or two sentence blurbs. Sorry

“They have to follow the regulations.”

They changed the regulations to exclude bank reserves and Treasuries from ‘risk assets’ they use to calculate the US Supplementary Leverage Ratio. Fortunately it looks like they never formed part of any liquidity requirements over here in Europe.

Banks hold the Treasuries swapped out for Reserves. That increases the banks income and doesn’t change the liquidity leverage ratio at all as Treasuries and Reserves are seen as equivalent in liquidity.

In fact since Treasuries can be sold to people other than banks, banks can offload Treasuries to reduce their leverage ratio (Tier 1 Capital/Consolidated Assets).

They changed the regulations to exclude bank reserves and Treasuries from ‘risk assets’ they use to calculate the US Supplementary Leverage Ratio.

Yes, I posted that on here last week. Not sure if they went through with it in the end. There was talk they backed off from the idea.

Neil, Those last two points you would need to take up with Mike and Matt.

If you go to Mike’s Twitter feed on the 13th April you will see and hear what they have been saying for years.

With a quote from Jamie Dimon.

I still can’t get my napper around all of it after thinking about it for over a year. So you would need to go to them directly and challenge them on it.

Either way, it is worth finding out if they are right or not and a debate worth having.

I’ve tried Derek. All I can see is a mistake in thinking – unless the USA has implemented the Net Stable Funding Ratio without telling anybody.

That’s the only thing that requires a higher weight ratio for government bonds over reserves that relates to flow of income.

The SLR change made sense because when you dump reserves on a bank’s balance sheet they can’t get rid of it, but it makes the SLR go down. So the bank had to dump assets it could get rid of – Treasuries – to get the ratio back in sync. And of course they couldn’t lend any more as that would throw the ratio out again. The Fed changed the rules (on April 1!) to remove reserves and Treasuries from the asset calculation.

I also read that Vleighe speech last week because I get notified of all BoE speeches as soon as they are published. I discussed it with Simon Cohen and we came to exactly the same conclusions. In fact Simon’s words were Vleighe very nearly lets the cat out of the bag.

You didn’t, however, Bill, mention the following – “As soon as possible before the end of the year, the DMO will scale up gilt issuance to repay the W&M balance.” This is exactly what I was expecting.

I did ponder writing to him and asking why he considers it necessary to exchange one Consolidated Government balance sheet item – reserves – for another CG balance sheet item – gilts. The only difference is that one is an electronic record and the other is a bit of paper with gilt edges (although it doesn’t actually have gilts edges these days).

regarding loans – the problem banks actually have is more likely to be:

1) a general increase in credit risk on their books now (bad debts)

2) a general decrease of new credit worthy customers

The first impact means more bad debts. The second means less profitable new customers.

From the banks perspective the reserves are assets in a risk free class. Increasing the reserves would decrease risks. But the reserves have low return. Overall effect is reduced income and reduced profit margin (~0.25% vs whatever spread on risky assests).

One thought I had – how are banks supposed to function and survive if everyone gets a “loan holiday” – doesn’t this mean zero income for the banks?

Neil,

Matt explains it like this…

The functional relationship is (A-L)/A = CsubL

A is total assets of the Depositories

L is total liabilities of the Depositories

CsubL is some regulatory constant of total leverage, not important what the constant is but just important that it is recognized as a mathematical constant <1 … iirc its around 0.1 or so if you examine the Depository's regulatory filings… just recognize it as a constant less than 1 … promulgated by govt regulators.

So if Fed buys USTs, they increase both A (Reserve Assets) at the Depositories and L (Deposit Liabilities) at the Depositories… former USD savers in USTs are left with USD savings in bank deposit accounts…

the two Accounting entries at the Depositories when Fed does asset purchases are credit Reserve Assets (LHS) and debit Deposit Liabilities (RHS)…

So you can see that ex post of this transaction, (A-L) in the numerator is unchanged and A in the denominator is increased so the ratio is decreased from the target constant level…

So the risk asset component of the Depository's total assets A has to be reduced (in either price or perhaps quantity … either is "bearish") so that then ex post of that adjustment internal to the Depositories, the Depositories come back into equality with the regulatory constant level …

At some point if Fed keeps adding these non-risk assets fast enough (first derivative dt) then banks cant add any more assets at all and the credit market shuts down until Treasury adds capital via investment like TARP was back in 2008…

When Treasury does this investment the accounting at the Depositories is A is increased while L is not increased (Treasury does not demand a Liability for the transfer of its USD reserves in the terms of the agreement) so the numerator (A-L) increases and the denominator A increases but since the constant is less than 1 the change in the numerator has larger regulatory effect ..

Its hard to predict what these people are going to do at any time but what you want to do generally is try to figure out when they are going to stop adding Reserves or perhaps when the Treasury is going to make a large capital investment in the Depositories to try to predict the timing of the nadir in prices…

We have apparently been in a post truth world for a long time where many false narratives such as those about the dangers of excessive government debt and deficits, what triggers inflation, how the banking system works, trickle down economics and all the other justifications for implementing the neoliberal agenda; can be so easily and effectively implanted into the minds of the technocrats, the political class and even most citizens by the oligarchy.

The fossil fuel supporting part of the oligarchy have also succeeded in creating sufficient doubt in the minds of most citizens about the true urgency and magnitude of the global warming crisis despite the warnings of effectively all the relevant scientific experts.

Perhaps this is nothing new as we have been collectively indoctrinated on many occasions to see the citizens of other nations in times of war as sub human, to fear punishment by deities, to shut out of our minds the suffering of our fellow human beings at home or abroad, to believe a particular group of innocent people as deserving of genocide and to believe our innocent fellow human beings as deserving death including by fire during the periods of executions for witchcraft.

Education of the masses can help reduce our vulnerability to false narratives but when the means of mass information and education are overwhelmingly in the hands of the oligarchs that seek to misinform we are all in deep trouble.

The world has not even started to address the global warming crisis despite all the talk and the current investments into clean energy generating capacity as global emissions are not only rising but accelerating. Substantial and effective change either happens in the next few years or we and the earth’s biosphere really are doomed. This means the global warming crisis is even more critical in terms of urgency and magnitude than the Covid-19 pandemic, any other likely pandemic or the ongoing degeneration and likely collapse of liberal democracy and our neoliberal economies.

Only nuclear war due to a false alert, accident or recklessness by either the US or Russia can kill us all quicker in a nuclear winter due to the crazy policy of both nations of retaining land based ICBM’s on ready to launch before first strike status – as detailed in Daniel Ellsberg’s letter which was hand-delivered to the office of each member of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives in late July 2019 and is available online. Note that this problem also has been universally ignored by those in authority and the populace remains ignorant.

Matt rewrites the equation like this:

(Asubrisk + Asubnonrisk – L) / (Asubrisk + Asubnonrisk) =. 0.095

At all times….

So you can see when they (for whatever reason) do a very large increase in the Asubnonrisk (Reserves are non risk assets at banks) which they are currently in process it appears of increasing them by 700b in just two weeks so Asubrisk has to be reduced…

in order to maintain the constant 0.095 regulatory ratio the govt puts on them…

They can do this by either selling risk assets or marking down the price of existing risk assets…

It appears what they have been doing lately is marking down the price of risk assets. equity Indexes taking another big hit last week …

If the Fed just buys the USTs from the banks (USTs are non risk) then there is no change the two entities just swap one non risk asset for another non risk asset … but that is not what is happening bank ownership of USTs is at all time highs…

Bank ownership of Corporate bonds, bond-tracking ETFs, and MBS are also at all time highs… Fed buying from public…. banks have to shed risk assets… bearish…

If they buy the bonds from banks then it is MMT “asset swap!” no change in the ratio..

However, if they buy them from the public then no…. if I own a Treasury and it is redeemed then i want to roll into new bond and Fed steps in front of me then I can’t buy one and am left with a bank deposit … That transaction results in both a new asset and a new liability at the bank , the asset is the new reserve the Fed created and the liability (to the bank ) is my deposit…

So (A-L)/A is decreased… numerator unchanged and denominator is increased… so risk asset levels have to be reduced to compensate for the additional non-risk the Fed added…

The Bank of Canada (BoC) has also been supporting all sorts of spending. The propaganda cover is that it is ensuring liquidity in financial markets. To do so it will buy $5 billion per week of federal government securities on secondary markets (QE), so $260 billion yearly. It is the first time the BoC has engaged in QE. It didn’t do it during the financial crisis but this time the government deficits are so large that the Bank needs to buy government securities on a vast scale. Strangely Justin Trudeau does not have a shoe box hidden in the back of his cupboard full of 100 dollar bills and handfuls of gold coins to cover the well over $200 billion deficit coming up (10% of GDP). The Bank has also announced it will buy $50 billion of provincial government debt in primary markets and that cap may increase as needed. This follows one province writing to the Prime Minister that it was unable to sell its debt and would not be able to meet payroll within a few weeks. Four days later the program to buy provincial debt was announced. The BoC will also buy $10 billion of corporate debt, a figure that may also increase if necessary. Other measures have been announced as well.

Fortunately the BoC has none of the ridiculous ”constraints” most other central banks have regarding the direct purchase of government securities. It has been buying around one quarter of federal government securities for a number of years now (need to check the exact number). In testimony before the Standing Committee on Finance on April 16th, 2020, only the Conservative Party finance critic, a very nasty character, pointed out the Bank would be creating a quarter of a trillion dollars out of nothing. For the governor of the Bank it was all about ensuring liquidity in financial markets. in the press there has been a bit of blather about paying it all back but so far not much. No doubt that will come once the crisis is past. I am hoping that progressives will not fall for that nonsense yet again. I am trying to counter it in the area where I am active.

Derek, this isn’t a comment on the economics or regulations because I genuinely don’t have a clue about those, but ‘economists make lousy mathematicians’ part 274. Why don’t economists simplify equations?

If (A- L) / A = C1, where C1 constant and 0 < C1 < 1 (equivalent to stating L < A).

Then

A / A – L/A = C1

1 – L/A = C1

L/A = C2, where C2 constant and 0 < C2 < 1 (again, equivalent to stating to L < A ).

In other words 100*C2 is the percentage of L w.r.t A. I know that's only a minor thing but it instantly makes the analysis you're suggesting a lot more obvious.

And then much clearer when you want to split A into A = A1 + A2.

L / (A1 + A2) = C2

If the claim is C2 need to be held constant, it's now much easier to observe how changes in A1 and L force a change on A2 in this form, than when A1 and A2 are appearing in both numerator and denominator confusing things.

Just a small thing, but good maths is about making everything as easy for yourself as possible!

PS. This wasn't in any way a dig at you!

PPS. The equivalent written in English, why say "the difference between assets and liabilities – where liabilities must be smaller than assets – should be 10% of assets", when you can much more simply say: "liabilities must be 90% of assets"?

No dig taken Michael,

I am just showing how Matt thinks about it.

To try and get to the bottom of it one way or another.

Michael B,

++1*

Last post on it by me until somebody can show definitively – when the system gets pumped full of reserves what effect it has on bank lending, if any.

I am not 100% sure either way. I would love to know though. My gut feeling is when the reserves get added in such volumes in such a short space of time something has got to give.

Big banks get Fed’s blessing to extend leverage amid market stress

“Leverage ratios are especially a problem in a crisis when large bank balance sheets grow as investors move out of riskier assets for the safety of a bank deposit,” Jaret Seiberg, a policy analyst for Cowen Washington Research Group, ”

“This frees up balance sheet capacity, particularly for leverage constrained banks, allowing them to engage more in balance sheet intensive activities like repo intermediation and market making in Treasuries,” said Credit Suisse strategist Jonathan Cohn. “By making those activities less costly, intermediaries will be better able to step in when there are one sided flows.”

https://www.americanbanker.com/articles/big-banks-get-feds-blessing-to-extend-leverage-amid-market-stress

There is still one crucial step missing and I am not convinced whether the last “cover” will ever be blown. I would argue the speech has not crossed the final frontier and the author is still firmly standing on New-Keynesian ground.

The loaded/Wickselian-framed/filled-with-bleach term “neutral rate of interest” is still there.

What if at some point in the distant future, organised labour regains its bargaining power and successfully demands increases in wages, while the prices of imported commodities also keep rising? This might lead to an increase in the rate of inflation. The reaction of New-Keynesians will be to declare that they have observed an objective increase in the “neutral” or “natural” rate of interest. Central bankers, following the Taylor rule, will then start jacking up the actual interest rates to chase that mythical parameter and suddenly the “molehill” of public debt becomes again a towering “mountain”, when the real rate of interest increases above the real GDP growth rate.

To neutralise the intellectual poison contained in neo-Wicksellian version of Loanable Funds Theory we need to argue that small to moderate changes in the rate of interest have a negligible impact on the rate of growth of GDP and the rate of inflation. (Only increasing the real rate of interest above the “hurdle rate” which is around 10%, leads to applying a handbrake to the whole economy, which then starts skidding and crashes). There are good econometric and theoretical arguments in support of this thesis. Only when we acknowledge this, the real rate of interest can be safely parked at zero.

Why do we need to pay people money for not spending? But this is precisely what the “1%”, who have a lot of money and have no opportunities left to spend it on investing in productive activities, demand from the rest. This description also includes the sponsors of so-called “Monetary Realism”.

Central bankers sing from the same hymn book. RBA governor Lowe came out with similar smoke and mirrors stuff the other day. In a speech on 21st April he said:

“I would like to restate that we are buying bonds in the secondary market and we are not buying bonds directly from the government. One of the underlying principles of Australia’s institutional arrangements is the separation of monetary and fiscal policy – that is, the central bank does not finance the government, instead the government finances itself in the market. This principle has served the country well and I am confident that the Australian federal, state and territory governments will continue to be able to finance themselves in the market, as they should.

While we are not directly financing the government, our bond purchases are affecting the market price that the government pays to raise debt. Our policies are also affecting the price that the private sector pays to raise debt. In this way, our actions are affecting funding costs right across the economy as they should in the exceptional circumstances that we face. But our actions should not be confused with the Reserve Bank financing the government.”

Whatever you say Phil.

“So if Fed buys USTs, they increase both A (Reserve Assets) at the Depositories and L (Deposit Liabilities) at the Depositories”

Yeah, that’s the Supplemental Leverage Ratio. The Fed took USTs and Reserves out of that calculation on April 1st.

For real – no joke!

Central bankers (other than the Chinese one of course whom we never hear from) will never stop employing smoke and mirrors.

They need them (deliberate subterfuge, bluntly) in order to prevent the public from ever realising that “central bank independence” – as exemplified in the quote from RBA governor Lowe cited above – is an utter sham. His Chinese counterpart wouldn’t bother (or wouldn’t dare) to allege publicly that he was “independent” – people would fall about laughing; but if I’ve understood Bill aright there’s no *essential* difference between their powers and his viv-s-vis the respective governments.

Ours however are forced to speak and act *as if* their independence were real. Hence the casuistic expositions they come out with. “Hymn-sheet” is apt; the whole farce is reminiscent of religious ritual. Hence too the tortuous accounting-conventions designed to conceal not to inform.

*None* of this nonsense will change this side of MMT’s analysis of how the system they’re using *actually* operates being unambiguously acknowledged as the only correct one. Personally I don’t expect to live to see that happen – if it ever does..

Central bankers: alas, definitely singing from the same hymn book.

More broadly I share the fears expressed by Andreas Bimba above that once the “one-off” covid crisis is past, fiscal deficits will again be convincingly used as the justification for permanent semi-austerity. I heard this very thing yesterday from a very well connected person.

Derek

“So (A-L)/A is decreased… numerator unchanged and denominator is increased… so risk asset levels have to be reduced to compensate for the additional non-risk the Fed added…”

Isn’t this actually the perfect example of what I meant with simplifying the equations, making reasoning easier…? Assuming the above is a quote from Matt, hasn’t he got that backwards?

If I understand what you/he is saying L is increased by the same amount as A1 (=A_nonrisk) so that A1 + A2 – L is unchanged? In this situation A2 (=A_risk) needs to go UP to maintain the ratio, not down. Again the confusion seems to come from A2 appearing in both numerator and denominator.

If you rewrite as I have:

L / (A1 + A2) = C2, where C2 = 0.905

Then an operation that adds dL liabilities matched by an equivalent dA1 non-risk assets, requires an additional dA2 = dL*(1 – C2) / C2 risky assets to maintain the ratio.

Which makes sense if you think about it – the original equation is saying you need to maintain liabilities at 90% of assets (or 90.5% to be precise). So anything you add (or take-away) needs to be in the same 9:10 ratio. So if you add 9 liabilities, you need to add 10 assets to match. Thus is you add 9 liabilities matched by 9 non-risk assets, you also need to add 1 risky asset. If you add 18 liabilities matched by 18 non-risk assets, you need to add 2 risky-assets etc.

I’m not very good at banking/investment speak, but doesn’t that understanding chime more with the Jonathan Cohn quote from your next comment re freeing up balance sheet capacity?

This isn’t just me going mad is it? Again, I’m not really sure of the underlying real world situation, just purely going off Matt’s equation:

“(Asubrisk + Asubnonrisk – L) / (Asubrisk + Asubnonrisk) =. 0.095”

In any case, from what Neil is saying re the change in regs, this may be a moot point anyway.