Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

The arms race again – Part 1

The Chair of the Finance Committee in the Irish Parliament invited me to make a submission to inform a – Scrutiny process of EU legislative proposals – specifically to discuss proposals put forward by the European Council to increase spending on defence. This blog post and the next (tomorrow) will form the basis of my submission which will go to the Joint Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation on Friday. The matter has relevance for all countries at the moment, given the increased appetite for ramping up military spending. Some have termed this a shift back to what has been called – Military Keynesianism – where governments respond to various perceived and perhaps imaginary new security threats by increasing defence spending. However, I caution against using that term in this context. During the immediate Post World War 2 period with the almost immediate onset of the – Cold War – nations used military spending as a growth strategy and the term military Keynesianism might have been apposite. These nation-building times also saw an expansion of the public sector, which supported expanding welfare states and an array of protections for workers (occupational safety, holiday and sick pay, etc). However, in the current neoliberal era, the increased appetite for extra military spending is being cast as a trade-off, where cuts to social and environmental protection spending and overseas aid are seen as the way to create fiscal space to allow the defence plans to be fulfilled. That trade-off is even more apparent in the context of the European Union, given that the vast majority of Member States no longer have their own currency and the funds available at the EU-level are limited. We will discuss that issue and more in this two-part series.

Recent Trends in Military Spending

It is clear that global defence spending has accelerated in recent years in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of the Ukraine.

Most of the Member States of the – North Atlantic Treaty Organisation – have increased the proportion of government spending devoted to military spending both relative to the size of their economies (measured by GDP) and as a share of total government spending.

Once the tensions associated with the Cold War were reduced, NATO nations reduced their focus on military expenditure.

In some cases, this was articulated as allowing social expenditures to expand.

The underlying premise, which for many currency-issuing nations was false, was that the governments had financial constraints and could not maintain the levels of military expenditure that were common in the immediate World War 2 period if the government wanted to increase spending elsewhere.

There was obviously a real resource constraint that would be binding at full capacity which would define some inflation ceiling in terms of total nominal expenditure.

But in the period after the OPEC crisis of the 1970s, economies rarely achieved anything close to full capacity and so those real resource constraints were non-binding for most countries during this period.

With the onset of renewed tensions on the European continent, and rumblings in Asia, as well as the rapidly deteriorating situation in the Middle East, the sense of security, which saw reduced focus on military expenditure by governments has been compromised.

We have seen remarkable statements from global leaders in recent years expressing that insecurity.

On March 30, 2024, the BBC report – War a real threat and Europe not ready, warns Poland’s Tusk – quoted Poland’s Prime Minister as saying that war is:

… no longer a concept from the past … It’s real and it started over two years ago …

We are living in the most critical moment since the end of the Second World War …

I know it sounds devastating, especially to people of the younger generation, but we have to mentally get used to the arrival of a new era. The pre-war era.

Similar remarks were made on May 22, 2024, by the then Secretary of State for Defence in his – London Defence Conference 2024 Defence Secretary keynote.

He reflected on the period of relative peace as a “golden era” compared to the present where “ruthless, rule-breaking” nations had moved the global environment from a:

… post-war to a pre-war era.

He said that “An axis of authoritarian states led by Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have escalated and fuelled conflicts and tensions.”

He said this justified a significant increase in government spending on the military.

And most governments have followed suit.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) report (February 12, 2025) – Global defence spending soars to new high – noted that:

In 2024, global defence spending reflected intensifying security challenges and reached USD2.46 trillion, up from USD2.24trn the previous year. Growth also accelerated, with the 7.4% real-terms uplift outpacing increases of 6.5% in 2023 and 3.5% in 2022. As a result, in 2024, global defence spending increased to an average of 1.9% of GDP, up from 1.6% in 2022 and 1.8% in 2023.

A Briefing Document prepared for the Australian Parliament – Rising global defence expenditure (June 4, 2025) – by Nicole Brangwin showed that there has been a 7.4 per cent real growth in global defence spending in 2024 (relative to 2023) and the proportion of GDP devoted to defence rose from 1.8 to 1.94 per cent.

It was also noted, that data from the Stockholm International Peace and Research Institute (SIPRI), shows there has been a “37% global increase in military spending over the last decade, with the single largest increase since the end of the Cold War occurring in 2024”.

And the expectation for 2025 is for an even greater increase.

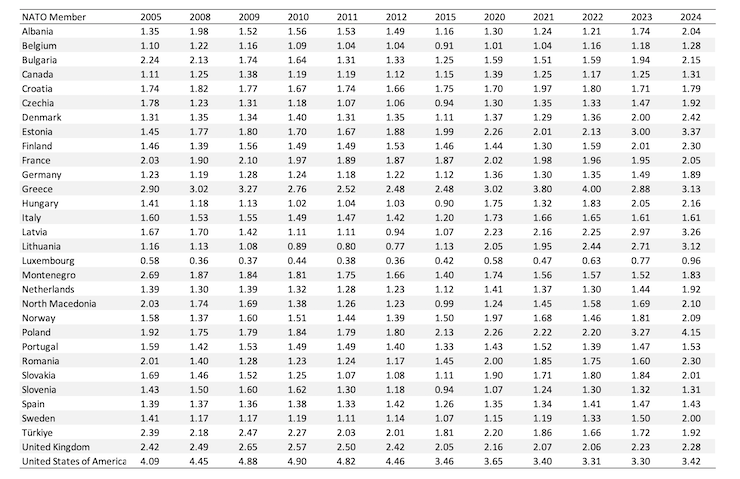

Table 1 shows the NATO Member-States spending on military as a percent of GDP for selected years.

Only four of the nations shown reduced their military spending as a percent of GDP.

Some of the countries closest in geographic terms to the Russian-Ukraine frontiers have expanded their military commitments relative to the size of their economies significantly.

Non-NATO countries have also followed suit.

Table 1 NATO Military Spending as a Percent of GDP, 2000 to 2025

Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure database.

Note: Iceland omitted due to lack of data.

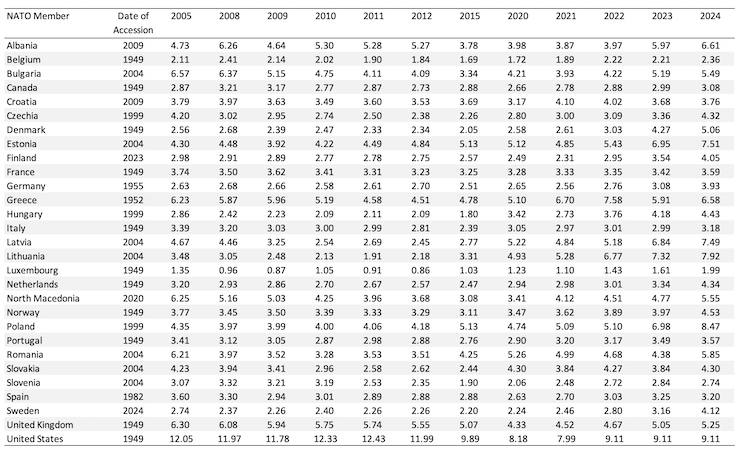

Many governments are also increasing the proportion of their total spending towards military purchases.

Table 2 NATO Military Spending as a Percent of Total Government Spending, 2000 to 2024

Source: Table 1.

Note: Iceland, Türkiye, and Montenegro omitted due to lack of data.

Military Keynesianism

As part of the political strategies that have been deployed to justify this rather significant realignment of government priorities, the term – Military Keynesianism – has been bandied around.

Military Keynesian refers to policy decisions to utilise defence spending as a growth strategy.

On April 14, 1950, the US Department of State and Department of Defense presented President Truman with the secret report – NSC 68 – or United States Objectives and Programs for National Security – which “provided the blueprint for the militarization of the Cold War from 1950 to the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s.”

The sentiments expressed in that document could easily relate to the current discussions about the need for more defence spending in the light of elevated security concerns.

We read that (p.4):

… the Soviet Union … is animated by a new fanatic faith1 antithetical to our own and seeks to impose its absolute authority over the rest of the world. Conflict has, therefore, become endemic and is waged, on the part of the Soviet Union, by violent or non-violent methods in accordance with the dictates of expediency. With the development of increasingly terrifying weapons of mass destruction, every individual faces the ever-present possibility of annihilation should the conflict enter the phase of total war …

The Report noted that unlike the Soviet economy, which it described as a ‘war economy’. the US had been devoted “to the provision of rising standards of living” (p.25) and that placed it at a military disadvantage.

To justify its recommendation for greater military spending by the US government, the Report stated (p.28) that:

… the United States could achieve a substantial absolute increase in output and could thereby increase the allocation of resources to a build-up of the economic and military strength of itself and its allies without suffering a decline in its real standard of living … With a high level of economic activity, the United States could soon attain a gross national product of $300 billion per year … Progress in this direction would permit, and might itself be aided by, a build-up of the economic and military strength of the United States and the free world …

This type of argument defined ‘military Keynesianism’ as a structural growth impulse, rather than a cyclical response to deficient economic cycle spending by the non-government sector.

However, that does not preclude using military spending to kick-start an economy during a recession.

In the latter context, it is widely argued that the Great Depression only came to an end when governments increased military spending to prosecute the Second World War effort.

For example, John Feffer in his 2009 article – The Risk of Military Keynesianism – reflected on the fiscal choices facing governments during the Global Financial Crisis and said:

With government budgets shrinking and the economic crisis putting greater pressure on social welfare programs, a shift of money from military budgets to human needs would appear to be a no-brainer. But don’t expect a large-scale beating of swords into ploughshares. In fact, if early signs are any indication, governments will largely shelter their military budgets from the current economic crisis.

Reference: Feffer, J. (2009) ‘The Risk of Military Keynesianism’, Foreign Policy in Focus, February 9.

There are many issues that have been raised against governments adopting military expenditure as a primary growth strategy, which we do not canvas here.

The problem we do address is that Feffer invoked the ‘trade-off’ card, like most commentators that want to criticise any buildup in military spending by governments.

Accordingly, to accommodate the increased defence spending, cuts to social and other spending are required.

The alternative way of saying this in the words of Feffer is:

At a time when we urgently need funds for the food crisis, the energy crisis, the climate crisis, the AIDS crisis, and other looming crises — all of which threaten human security — military spending is nowhere near the top of the global agenda.

Which implies some financial constraints on governments and within that constraint there are better things for governments to spend their ‘constrained’ cash on than defence procurements.

This narrative is dominant in the current discussions about the need for increased military spending.

On June 2, 2025, the UK Guardian article – Labour pushes ‘military Keynesianism’ to win support for defence spending – reported that:

This “military Keynesianism” was emphasised on Sunday morning when ministers announced plans to build six new munitions factories, which would in time create 1,000 jobs and support a further 800, the Ministry of Defence said.

The British government has claimed that the rapid expansion in military spending would help “create skilled jobs, particularly outside London, such as at shipyards in Barrow, Devonport, Glasgow and Rosyth.”

They justified “diverting funds from overseas development aid” the government could reinforce “the British industrial base”.

There is some truth to that argument even though the government’s decision is being driven by the fiction that it faces a financial constraint.

The truth is that diverting spending that benefits the rest of the world (the ODA) and channelling it into the domestic economy will enhance GDP and employment growth in Britain.

The morality of that decision is highly questionable.

But there is another issue that is most relevant in the case of the European Union’s plan, which we scrutinise later in this submission.

Notwithstanding whether it is desirable or not for Britain to be joining the ‘arms race’, if there is real resource space to accommodate the extra nominal spending on defence procurements in Britain without reaching an inflationary ceiling, then the British government could have simply increased its spending on the military without compromising its global responsibilities to support poorer nations through ODA.

The fact that they claimed the diversion was necessary reflects their adherence to flawed fiscal rules that assume the British government is financially constrained in terms of its sterling spending capacity.

We will return to that issue in Part 2.

The other interesting aspect of the data presented in the Tables above is that governments did not seem to rely on military expenditure during the GFC to restore growth to their economies.

For the NATO countries, military spending as a share of GDP fell between 2008 and 2012 in 22 out of the 31 NATO Member States for which there is compatible data, while 2 of the States reported stable military spending relative to GDP.

So military Keynesian was not seen as a dominant fiscal strategy during the GFC.

It is also not a good characterisation of what is happening in the current environment, a point we will turn to in Part 2.

Conclusion

In Part 2, I will focus on the specific proposals being put forward by the European Commission to increase military spending.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Having the Russian scarecrow belief, is good business for western MIC.

Keeping 800 military bases abroad is costly.

Portugal spends about 4 billion euros every year to keep Nato bases running, while keeping paltry armed forces at home.

We got 34 fighting tanks. I wonder how many seconds it would take to destroy the whole fleet.

Anyway, many cuts on social spending are one their way, to pay for the announced extra military spending, that is said to go up to 2% of GDP.

We are going to import heavy equipment and ammunition to store in leaky arsenals.

What for?

To defend ourselves from the Russians, who took 3 years to take less than 20% of Ukrainian territory (even though Ukraine is beeing backed by the whole nato contraption – oops, 4 billion are not enough already…).

The fact that the Russians have a relatively scarce population (the Russian GDP is on the level of France’s) and is unable to invade much more, doesn’t matter.

The fact that none of those 800 bases are Russian bases, doesn’t matter.

The fact that military spending is useless for economic purposes, doesn’t matter either.

We are forced to accept the unelected officials mantras, just like the one about Gaza.

The outcome will be the usual: disaster!

IIRC, in the operational tempo of the early months of the SMO, 34 tanks was about two weeks worth.

That must be the special charm of Military Keynesianism. If you get really serious about it you can generate astonishing levels of nominal spending.

Tell them that financing military spending trough deficits would increase money supply and that would be very beneficial to the economy.

If they don’t get economic analysis of effects of deficit spending on the economy from MMT economists, then who are they going to get it from?

MMT will finally be able to attract support from the right.

Hepion writes:

“Tell them that financing military spending trough deficits would increase money supply and that would be very beneficial to the economy.”

Indeed, which is the US approach since Clinton ( the last to ‘balance the budget’), with the US spending more on ‘defence’ than the next ten nations combined, with the US being the fastest growing G7 econmomy since the GFC while its defict has soared – a nod to Keynesian deficit spending’?