In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

New central bank initiative shows governments are not financially constrained

On November 16, 2011 by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) published a – Discussion Paper – Implementing Basel III liquidity reforms in Australia – which details how the prudential regulator plans to implement the new Basel III reforms which aim “to strengthen the liquidity framework for authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs)”. in that paper, APRA indicated that there were not enough assets in the Australian financial system to satisfy the new liquidity requirements. In other words, there are not enough government bonds on the issue that the banks can use for this purpose. This is a consequence of the excessive pursuit of government surpluses over the last 16 odd years. APRA indicated that a country-specific solution to this asset would be required. in this context, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) a new facility – the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF), which will provide high-quality liquidity to the commercial banks to allow them to meet the Basel III liquidity requirements. What the CLF demonstrates once again is that a currency issuing government is not financially constrained and can maintain integrity of the of the financial system and purchase any goods and services that are available for sale in its own currency any time that it chooses.

APRA, the “prudential regulator of the financial services industry” in Australia, was responding to the release of the Basel III liquidity framework in September 2008 by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) – Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision.

In this blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – I outlined the system of banking supervision based on capital adequacy requirements which has been developed by the Bank of International Settlements.

You might also like to read this blog – Banks might be forced to buy government bonds … – for more discussion on this point.

As further background new might like to read this blog – Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained.

APRA indicated that it would implement “the quantitative requirements in the Basel III liquidity framework to the larger authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs), with only minor modifications”. Such modifications were allowed under the framework to allow national regulators some discretion in specific regional situations.

The two new “minimum global standards” in the Basel III liquidity framework are:

- a 30-day Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) to address an acute stress scenario; and

- a Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) to encourage longer-term resilience.

The LCR requires that ADIs have “sufficient high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to survive a significant liquidity stress scenario for a minimum period of 30 calendar days”.

In the Discussion Paper, APRA “proposes that ADIs be required to maintain an LCR of no lower than 100 per cent”.

Modern monetary theory (MMT) teaches us that that governments, who issued their own fiat currency, do not have to issue bonds in order to spend. We say that such governments are not revenue-constrained in their spending decisions.

We have already seen a classic demonstration of this in Australia in 2002.

In this blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – I discussed the way that government bond markets get caught up in special pleading. Essentially, public bond issuance, while an unnecessary act for a government that issues its own currency, provides corporate welfare to the financial market casino.

I provided the following Australian example, which is worth repeating.

In 2002, after 6 years of federal budget surpluses the bond market became very thin. At the time, with the increasing fiscal drag on the economy coming from the federal surpluses, the only way the growth could be maintained (which was, incidentally, the only way the surpluses could be achieved) was because households built up record levels of debt (relative to disposable income) as a way of maintaining growth in consumption expenditure.

Real wages growth was subdued and being outstripped by productivity growth (hence the wage share was falling). It was an unsustainable growth strategy because the private sector cannot increasingly accumulate debt.

The stock adjustments arising from the surpluses saw the outstanding stock of federal government debt fall dramatically as the government systematically undermined private wealth holdings. As this was occurring, the key financial market players who had been vehemently demanding the conservative government retrench the welfare state, pursue even larger fiscal surpluses and introduce widespread deregulation started to realise that the thinning bond markets were not in their best interests.

The upshot was that the Government announced the Review of the Commonwealth Government Securities Market in December 2002.

The Review was announced after the industry had lobbied the federal government relentlessly to ensure that their corporate welfare (government bond issues) were maintained.

You can read the Treasury Discussion Paper along with all the public submissions, including that produced by The Centre of Full Employment and Equity (written by myself and Warren Mosler) if you are interested.

In our Submission, we addressed several claims made in the Treasury Discussion Paper, which was released to accompany the review. We also addressed the claims made by the Sydney Futures Exchange that by eliminating the CGS market the government would “deny superannuants an A$ denominated (default) risk free investment for their retirement planning at a time of an ageing population and in a mandatory superannuation environment.”

We noted that what is not often understood is that Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) are in fact government annuities. That is, guaranteed income streams.

We also wondered whether the “free market” lobby that were making these points (about superannuation losing out) really wanted the private sector to have access to government annuities rather than be directing real investment via privately-issued corporate debt, as an example.

The point is also applicable to claims that CGS facilitate portfolio diversification. Why would Australians want to provide government annuities to private profit-seeking investors? This clearly interferes with the investment function of private markets.

We argued that direct government payments be limited to the support of private sector agents when failures in private markets jeopardise real sector output (employment) and price stability.

Later in our Submission we detailed that this support should be largely confined to providing employment guarantees and that government endeavour be focused on the provision of first-class education, health, aged care and other activities which unambiguously advance public purpose.

In this context, we also demanded a comparison of this method of retirement subsidy against more direct methods involving more generous public health and welfare provision and pension support. No such comparison was ever forthcoming from the government or its private sector puppeteers who were both rushing to increase the surpluses and had actively promoted the reduction of welfare benefits that were being received by the disadvantaged Australians and wide scale deregulation and privatisation.

The financial markets had been leading voices at the time (and still) demanding the government cut its deficit and get the “public debt-monkey” off the back of the economy. The neo-liberal government fell into line and started to run massive surpluses (even though unemployment and underemployment was very high) and regularly announced how it was retiring the public debt.

It was truly ironical while the government was acting according to the wishes of the financial sector – once it became obvious that the “corporate welfare” part of the deal was threatened – the very same financial players sought reassurances from government that a minimum volume of public debt would be issued each year even though (in their own words) it was not required to fund any deficits – there were surpluses after all at the time.

It was incredible really that these characters who kept the line that debt is used to fund deficits – suddenly (but subtly) shifted their line demanding more debt even though there was in their own logic no need for it. The public never really were party to the debate – it was rather technical – and so they never really were exposed to the double-standards operating.

The whole Review and the subsequent decisions highlighted the hypocrisy of the “debt-monkey lobby”. It became clear to those in the know that the actual agenda operating was that the financial organisations (banks etc) wanted to get rid of all government support (welfare) unless it impinged on their own ability to live the high-life. Then it was fine.

In our Submission, we argued that the roles identified by IMF, Australian Treasury and the Sydney Futures Exchange among others for the government bond market are not justifiable on public good grounds. They were classic examples of special pleading by an industry sector for public assistance in the form of risk-free government bonds for investors as well as opportunities for trading profits, commissions, management fees, and consulting service and research fees

Furthermore, and ironically, their arguments are inconsistent with rhetoric forthcoming from the same financial sector interests in general about the urgency for less government intervention, more privatisation, more welfare cutbacks, and the deregulation of markets in general, including various utilities and labour markets.

Specifically, government price level intervention into private markets is typically challenged by economists on efficiency grounds. What is not widely understood is that government bonds issuance is a form of government price level intervention in interest rate markets. The burden of proof falls on those arguing in favour of government bonds issuance to show that the market in question is incapable of viable operation without government intervention and will, unassisted, produce outcomes detrimental to the macro priorities of full employment and price stability. No such arguments have ever been convincingly presented.

We also noted a larger irony in the entire discussion – as all parties to the debate, including the Treasury omitted discussion of the primary role of government bonds in the context of a flexible exchange rate system – that is, to support the term structure of interest rates rather than to fund government expenditure. This omission subsequently undermined much of the validity of the arguments advanced.

Even using mainstream logic, there was no need for the Australian government to be issuing any debt, given that it was running increasing fiscal surpluses. However the fact that it out of financial pressure and continued issuing debt despite ongoing fiscal surpluses demonstrated categorically that the debt-issuance had nothing to do with financing government spending.

Now with Basel III liquidity rules demanding high quality assets including government debt be held by commercial banks we get a clearer picture of the role of government debt plays in the financial markets.

Another way of thinking about this, which was the inference drawn in the previous blog – Bond markets require larger budget deficits – is that sovereign governments, which have no solvency risk, should be able to run much larger fiscal deficits at low yields for the foreseeable future, such will be the demand for government bond issues.

In terms of the LCR requirements, APRA say that:

As is well recognised, the supply of HQLA in Australia is insufficient to meet the Australian dollar liquidity requirements of ADIs. As such, APRA and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) propose to allow an ADI to use a secured committed liquidity facility with the RBA, for payment of a fee determined by the RBA, to cover any shortfall in Australian dollars between the ADI’s liquidity needs and its holdings of HQLA. This alternative treatment is envisaged by the Basel III liquidity framework.

APRA will require ADIs to demonstrate that they have taken all reasonable steps towards meeting their LCR requirements through their own balance sheet management, before relying on the RBA facility.

Sound like another chapter in the history of corporate welfare is about to start.

What is the “committed liquidity facility” that the RBA is to offer the ADIs?

First some background.

The aim of the LCR requirements is that each ADI will have an “adequate level of unencumbered, high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) that can be readily converted into cash to meet its liquidity needs for a 30-day period”.

APRA will require that ADI’s have at least as many HQLAs as they have total net cash outflows over the next 30 calendar days (that is, a ratio of 100 per cent).

This requirement will be continuously enforced.

Under Basel III, “two buckets based on the liquidity characteristics of the assets” will make up the definition of the HQLA acceptable under the LCR requirements. The highest quality bucket can comprise 100 per cent of the total stock of HQLA.

Basel III defines the highest quality bucket (Level 1 HQLA) as comprising:

- cash;

- central bank reserves (to the extent that these reserves can be drawn down in times of stress); and

- marketable securities representing claims on or claims guaranteed by sovereigns, quasi-sovereigns, central banks and multilateral development banks, which have undoubted liquidity, even during stressed market conditions, and which are assigned a zero risk-weight under the Basel II standardised approach to credit risk.

40 per cent of the LCR portfolio can be held in assets defined areas Level 2 HQLA which comprise “assets with a proven record as a reliable source of liquidity”.

APRA has interpreted the Level 1 HQLA requirements (which they term HQLA1) in the following way: cash, balances with the RBA, and Commonwealth Government and semi-government securities. They also have indicated that there are “no assets that qualify as HQLA2”.

So the Australian rules governing the LCR requirements will likely be more strict than applied elsewhere given that only HQLA1 assets will will be allowed for our ADIs.

APRA also recognises that there is an “insufficient supply of HQLA” in Australia and so alternatives will have to be developed to conform with the Basel III liquidity framework.

APRA say that one alternative is:

… to allow banking institutions to establish contractual committed liquidity facilities provided by their central bank, subject to an appropriate fee, with such facilities counting towards the LCR requirement.

On November 21, 2011, APRA held a conference in Sydney – APRA Basel III Implementation Workshop 2011. You can access some of the APRA staff speeches HERE.

In a speech – Basel III – Impact and Implications for Australia – by APRA Executive General Manager Charles Littrel we learned that the LCR requirements would be introduced in 2015 and as noted above ADIs will be required to at least maintain a LCR of 100 per cent.

In terms of APRA modelling for 2011, the LCR was around 31 per cent. They estimated that qualifying assets (HQLA1) totalled $A132 billion and net cash outflows were $A429 billion.

That is a massive gap to make up. APRA proposed the following that to “close the gap” the ADIs should reduce the net cash outflows (by increasing retail deposits, introduce new products that, for example, extend beyond 31 days) and increase liquid assets.

They recognise that there is a “very limited stock” of HQLA1 assets outside of the banking system.

The third option is to introduce alternative arrangements – lines of credit from the RBA.

The Deputy Governor of the RBA gave a speech at the same workshop where he outlined in more detail the to the proposed expansion of the RBA lines of credit – the so-called – The committed liquidity facility.

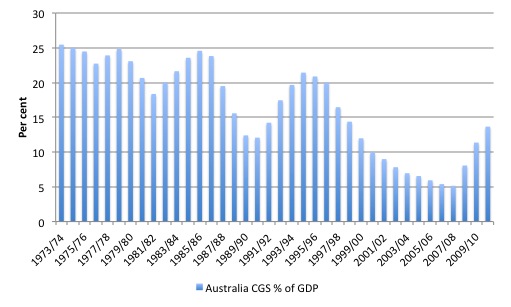

To put his comments in perspective, the following graph shows the outstanding Commonwealth Government Securities as a proportion of GDP since the 1974/75 financial year (data available at http://www.rba.gov.au).

The current ratio is about 13.7 per cent (total outstanding CGS in 2010/11 was $A191,291 billion).

While the RBA Deputy Governor characterises this recent history as being the “result of prudent fiscal policy” I prefer to think about it in terms of persistently high unemployment and underemployment, degraded public infrastructure, and record levels of household indebtedness.

Without the massive buildup in household debt over the last 15 years, the Australian government would not have been able to run these surpluses and maintain such a low public debt ratio (given current institutional arrangements with respect to the issuance).

The RBA Deputy Governor captures the challenge in this way:

At the moment, the gross stock of Commonwealth debt on issue amounts to around 15 per cent of GDP, state government debt (semis) is around 12 per cent of GDP … These amounts fall well short of the liquidity needs of the banking system. To give you some sense of the magnitudes, the banking system in Australia is around 185 per cent of nominal GDP. If we assume that banks’ liquidity needs under the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) may be in the order of 20 per cent of their balance sheet, then they need to hold liquid assets of nearly 40 per cent of GDP.

He then noted that bank reserves could be used for HQLA1 purposes. In Australia these are called “exchange settlement accounts” which more neatly captures the purpose of these accounts.

Bank reserves or exchange settlement accounts are held at the Central bank on behalf of the commercial banks and facilitate the payments system. That is they ensure that every day each of the commercial banks can clear up all the claims that are made on them as a result of the plethora of transactions that occur each day.

The Deputy Governor noted that the commercial banks could “significantly increase the size of their ES balances to meet their liquidity needs”.

However that would increase the RBAs balance sheet “considerably” and the challenge would be to identify ” what assets it would be willing to hold against the increase in its liabilities”.

Once again, the RBA “would be confronted by the same problem of the shortage of assets in Australia outside the banking system”.

As an aside to the blog theme and in relation to the ES balances, the RBA noted that:

Within the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy framework, the supply of ES balances is effectively market-determined. That is, the Reserve Bank stands ready to supply whatever quantity of ES balances is necessary (against eligible collateral) to keep the cash rate trading at the Board’s target.

Which tells you that banks can never run out of reserves in a modern monetary system. The central bank is always able to supply whatever liquidity is deemed necessary by the commercial banks to satisfy the payments system and maintain financial stability.

Back on theme, the Deputy Governor also noted that another alternative would be for the government to:

… increase its debt issuance substantially with the sole purpose of providing a liquid asset for the banking system to hold. Again, it would be confronted with the problem of which assets to buy with the proceeds of its increased debt issuance. Moreover, it would be a perverse outcome for the liquidity standard to be dictating a government’s debt strategy.

This statement reveals the bias of the central bank towards the Treasury running fiscal surpluses. Their lack of imagination with respect to the challenges that the Australian economy faces that could be addressed effectively with higher deficits is telling.

Of course, under current arrangements, the government could simply run larger deficits and ensure that the economy was growing fast enough to fully employed the available workforce.

At present, there is substantial scope for larger deficits. However it is unlikely, given the scale of HQLA1 assets that will be required to satisfy the LCR, but the deficits that would generate full employment would be sufficient for the LCR purposes.

The RBA’s solution is to introduce the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF).

How does this work?

In the RBA Media Release (November 16, 2011) we learn that the CLF:

… will enable participating ADIs to access a pre-specified amount of liquidity by entering into repurchase agreements of eligible securities outside the Reserve Bank’s normal market operations. To secure the Reserve Bank’s commitment, ADIs will be required to pay ongoing fees. The Reserve Bank’s commitment is contingent on the ADI having positive net worth in the opinion of the Bank, having consulted with APRA.

So this will not be part of the normal repurchase agreements (that is, the so-called discount window) which ensures that the banks always have reserves when needed. The CLF will essentially provide the banks with cash to enable them to meet the LCI requirements at all times. The cash will be provided to the banks added an extremely low price (15 basis points per annum).

The collateral that the RBA will require “will include all securities eligible for the Reserve Bank’s normal market operations” in addition to other lower quality assets (mainly “self-securitised residential mortgage-backed securities”).

Of course, “(s)hould the ADI lack a sufficient quantity of residential mortgages, other ‘self-securitised’ assets may be considered, with eligibility assessed on a case-by-case basis”.

The memo says that the RBA “has discretion to broaden the eligibility criteria and conditions for the various asset classes at any time”.

In other words, the RBA will do whatever it takes to provide liquidity to the banks such that they can satisfy the LCR requirements.

What is the basis of the fee that will be charged?

The logic is as follows. The RBA sought to “to replicate the effect in other jurisdictions where a bank could meet its liquidity needs of holding eligible assets in a liquid market, solely through holding government paper”.

but they point out That the yield spread between government bonds and other eligible assets includes “compensation for a variety of risks, including credit and liquidity”.

The RBA claim that the only part of the differential they wish to address is the liquidity component.

They conclude that the value of a one-month liquidity premium ” is not very much in normal circumstances, generally less than 10 basis points”.

In other words, the fee should be very low.

The other observation is that:

… Could the market has underpriced liquidity in the past. Consequently, it is appropriate to levy a fee which is greater than implied by a long run of historical data. The net outcome is thus a weighted average of a relatively low liquidity premium in normal times and a much higher liquidity premium in stressed times.

The RBA also recognise that the alternative way in which the banks can satisfy the LCI requirement is by building up exchange settlement accounts (reserve balances).

Under current conditions, the banks can either hold the reserve balances overnight and earning 25 basis points below the cash rate from the RBA, or they can lend the excess reserves into the cash market.

The RBA notes that the latter option is “not risk-free” (that is, banks lending to each other carries some credit risk) and so “a fee a little less than the 25 basis points”:

… has been deemed necessary to ensure banks did not have the incentive to meet the LCR by holding unduly large amounts of ES balances.

but

You might also like to read the following Ftalphaville Blog from November 2011.

Conclusion

What the RBA announcement confirms once again is that the Consolidated government sector can always provide liquidity to the private sector. In the case of the central bank, this capacity is typically use to ensure integrity of the payment system (cheque clearing system) and financial stability via liquidity guarantees.

In the case of the Treasury, this capacity means that the currency-issuing national government can always purchase goods and services that are for sale in the currency it issues. That includes any idle labour that has no demand in the private sector.

It means that overall there is no financial constraint on a currency-issuing government no matter how we disguise that by institutional arrangements with respect to debt issuance or other nifty central bank schemes designed to ensure that the non-government sector banks can never be short of liquidity.

Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point.

That is enough for today!

I notice that shrinking the size of the private debt issuance so that it matches the available high quality assets isn’t mentioned.

What is the point in a capital restriction that doesn’t then restrict the private debt limits?

So what the central bank is saying here is that it will pretend that the banking system is secured on ‘high quality assets’, but offer a back street dodgy deal so that any old thing the bank wants to call an asset can be swapped for cash from the central bank as required. And that then beefs it up to become ‘regulatory capital’ which can be leveraged.

So we’re back to regulatory capital being about price, not quantity.

Wouldn’t it be easier to just crash the system now and get it over with?

2015 is a long time in the future given Australia’s housing bubble, the possible worthlessness of MBAs, what I read as a $300bil exposure to European debt, and the possibility of GFC2. I also have a feeling that there’s moral hazard built in here too – banking has been very profitable these last few years so there’s no love lost on ordinary Australian people. The 1% keeps on getting richer. Where to next?

Neil, Bill

I was wondering if you know anything about the UK government debt labelled as “banking interventions” issued presumably as a remedy to the financial crisis – if I recall correctly it amounted to a few hundred billion pounds.

Was this debt auctioned as normal? and if so was there an equavalent amount of government spending? if so where was this money spent?

Alternatively, was the debt just created and given to the banks as risk-free assets they could then use as collateral or something?

Kind Regards

Charlie

“the primary role of government bonds in the context of a flexible exchange rate system – that is, to support the term structure of interest rates rather than to fund government expenditure”

This is not true. The term structure can exist without government bonds because it is a derivative based on the expectations of future central bank policy. Government bonds simply provide a tradable *cash* instrument. However, since banks are levered players in interest rates and since banks are players on the interbank swap market, they do not really care about the existence of government bonds for purposes of interest rate term structure.

The primary purpose of government bonds is thus:

a) to withdraw interbank liquidity and thus make life of central bank easier (in other words make fiscal policy neutral to interest rate policy) and

b) to buy some of the maturity transformation from the non-banking sector (in other words to give access to coupons to any player and not just banks).

“Again, it would be confronted with the problem of which assets to buy with the proceeds of its increased debt issuance.”

Is this really a problem? There are trillions of dollars of liquid financial assets which can be acquired without “active” security selection.

Besides, if you believe in monetary policy, then you pretty much *need* this tool because of the zero lower bound.

CharlesJ,

The reconciliation is published at the back of the Public Sector Finance report.

Currently the financial intervention debt totals £112.4bn and is reducing at a rate of about £1bn per quarter. How much of this is real and how much is imputed is difficult to determine from the statistics.

It looks like that money was covered by Gilts/National Savings in the normal fashion, and it was spent propping up the banks – paying out depositor protection, and injecting equity into the banks. I would imagine the majority of it remained ‘saved’.

Thanks Neil,

There is a link to an article about the banking interventions on the ONS web site, but the pdf does not open for some reason. The link is in the notes at the bottom of the monthly report about public sector debt.

Thanks again

Why are banks and other financial institutions privately owned in the first place?