Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

While the US government is sovereign in its own currency, increased nominal expenditure on health care will still reduce the real resources available for other uses and so political choices have to be made.

The answer is False.

The question was designed to ensure you are careful in articulating each of the concepts mentioned accurately and not drawing quick but false associations.

The first part of the question lures you into thinking about a series of other propositions that follow for such a government. So we know that the following summary features describe a government that is sovereign in its own currency:

- A national government which issues its own currency is not revenue-constrained in its own spending, irrespective of the voluntary (political) arrangements it puts in place which may constrain it in spending in any number of ways.

- The only constraints facing such a government other than the political pressures it has to manage are real – there must be real resources available for sale for government spending to purchase.

- A sovereign government can buy whatever is for sale at any time but should only net spend up to the desire by the non-government sector to save otherwise nominal spending will outstrip the real capacity of the economy to respond in quantity terms and inflation will result.

- A deficiency of spending overall relative to full capacity output will cause output to contract and employment to fall.

- Government net spending funds the private desire to save while at the same ensuring output levels are higher than otherwise.

- A government deficit (surplus) will be exactly equal ($-for-$) to a non-government surplus (deficit).

- Public debt issuance of a sovereign government is about interest-rate maintenance and has nothing to do with “funding” net government spending.

The “knee-jerk” answer would be true if after a careless reading you reasoned that when governments spend they use up real resources in the economy.

But the questioned asked you to relate nominal expenditure to availability of real resources. All spending is nominal but whether it has a real effect depends on state of overall demand in the economy and also on price movements in particular areas of the economy.

You could imagine that with the health care providers holding market power which translates into price setting power that increased demand for health care resources could be met by price adjustments and draw in no further real resources into the sector.

Question 2:

In 2001, Japan defied the ratings agencies who had downgraded their sovereign debt. They refused to alter their fiscal commitments despite constant pressure to cut the deficit. Given that countries such as Greece and Portugal are unlikely to be expelled from the EMU if they continue to exceed the Stability and Growth Pact conditions, they should similarly resist the demands of the ratings agencies for increased fiscal austerity and thus spread their fiscal adjustment over a longer period which would inflict less damage on their nations.

The answer is False.

This tests whether you really understand the dilemma that the Eurozone nations are facing. You cannot say very much about the constraints facing a Eurozone nation from what Japan did. Relating to the dot points describing a sovereign nation (above in Question 1), Japan is fully sovereign.

The Bank of Japan sets the interest rate and can control the yield curve at longer maturities should it want to. The Japanese government also faces no default risk on its sovereign debt because it can never become insolvent in relation to obligations issued in its own currency.

In Japan’s case it also helps (a bit) that they have particular cultural proclivities and the domestic government bond market is seemingly inexhaustible. Further, the Japanese government is smart and does not issue public debt denominated in any foreign currency.

Even if the bond markets were not “loyal” (as some commentators put it) in Japan, ultimately the Japanese government can spend without off-settting bond sales anyway. That is the option available to all sovereign governments in a fiat monetary system.

So the sovereign rating agencies have no real traction in this case. They can downgrade and hector all they like but their interventions will be meaningless.

None of this applies to an EMU nation. While it is clear that the SGP conditions are binding on EMU nations (violation attracts a fine) the discipline is maintained via moral suasion in the main. Bullying! France and Germany in the past have had extended periods where they exceeded the deficit to GDP limits of 3 per cent.

And, clearly, in the current crisis, several nations are well over the limits.

But this could not go on for very long (as we are seeing in the Greek case). An EMU nation does not set interest rates in its country and cannot control the yield curve in any way. The ECB in Frankfurt has that function.

Further, while an EMU nation can run a deficit they have to “fund” it because they do not issue the currency of the zone. They have to fund it via tax revenue, bond issues and/or asset sales (privatisations). In a recession, with tax revenue falling and the automatic stabilisers driving the deficits higher, the call on bond markets increases for a government in this position.

The auction arrangements that underpin the debt issuance functions rely on the attitudes of the private markets to risk and return for there ongoing success.

Given that an EMU nation faces insolvency risk in all obligations denominated in Euros (it is like a foreign currency obligation to a sovereign currency nation), perceptions of risk play an significant role.

Insolvency could come about via a bank run – where the government could not bail out its banks. Or it might come from the governments being unable to finance on-going spending commitments because the bond markets will no longer buy their debt.

In this case, the assessments of the credit rating agencies matter. They can force the government to pay increasingly onerous interest burdens on newly-issued debt and ultimately influence markets to stop buying the debt.

Further, the national central banks in each EMU country are part of the EMU system with the ECB at the head. The EMU system is largely decentralised with the NCPs performing most of the day to day monetary functions – liquidity management etc. To a some level, the NCBs can buy the debt of their government and cash it in via the ECB.

But the ECB has rules relating to the quality of the assets it will accept as collateral through these arrangements. They use credit rating assessments to determine what is an acceptable asset. So again, the credit rating agencies can render the debt instruments offered by an EMU government worthless.

Defiance is not an option. The options in these cases are either to implement “credible” fiscal austerity packages to the detriment of the citizens of the nation (I use credible in the sense that the corrupt ratings agencies might use it); default on the debt (and then what?); or leave the EMU system altogether and reinstate the currency sovereignty of the nation (which might also require a default on Euro-denominated debt).

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

Question 3:

Fiscal rules such as are embodied in the Stability and Growth Pact of the EMU will continually create conditions of slower growth because they deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary.

The answer is False.

One word in the question renders this proposition false. I had originally worded the question (following EMU) “will bias the nations to slower growth” etc which is true and I considered that too easy.

The fiscal policy rules that were agreed in the Maastricht Treaty – budget deficits should not exceed 3 per cent of GDP and public debt should not exceed 60 per cent of GDP – clearly constrain EMU governments during periods when private spending (or net exports) are draining aggregate demand.

In those circumstances, if the private spending withdrawal is sufficiently severe, the automatic stabilisers alone will drive the budget deficit above the required limits. Pressure then is immediately placed on the national governments to introduce discretionary fiscal contractions to get the fiscal balance back within the limits.

Further, after an extended recession, the public debt ratios will almost always go beyond the allowable limits which places further pressure on the government to introduce an extended period of austerity to bring the ratio back within the limits. So the bias is towards slower growth overall.

It is also true that the fiscal rules clearly (and by design) “deprive the government of fiscal flexibility to support aggregate demand when necessary”. But that wasn’t the question. The question was will these rules continually create conditions of slower growth. The answer is no they will not.

Imagine a situation where the nation has very strong net exports adding to aggregate demand which supports steady growth and full employment without any need for the government to approach the Maastricht thresholds. In this case, the fiscal rules are never binding unless something happens to exports.

The following is an example of this sort of nation. It will take a while for you to work through but it provides a good learning environment for understanding the basic expenditure-income model upon with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) builds its monetary insights. You might want to read this blog – Saturday Quiz – March 20, 2010 – answers and discussion – to refresh your understanding of the sectoral balances.

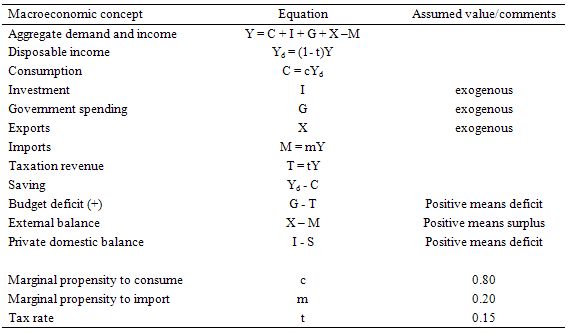

The following table shows the structure of the simple macroeconomic model that is the foundation of the expenditure-income model. This sort of model is still taught in introductory macroeconomics courses before the students get diverted into the more nonsensical mainstream ideas. All the assumptions with respect to behavioural parameters are very standard. You can download the simple spreadsheet if you want to play around with the model yourselves.

The first Table shows the model structure and any behavioural assumptions used. By way of explanation:

- All flows are in real terms with the price level constant (set at whatever you want it to be). So we are assuming that there is capacity within the supply-side of the economy to respond in real terms when nominal demand (which also equals real demand) changes.

- We might assume that the economy is at full employment in period 1 and in a state of excess capacity of varying degrees in each of the subsequent periods.

- Fiscal policy dominates monetary policy and the latter is assumed unchanged throughout. The central bank sets the interest rate and it doesn’t move.

- The tax rate is 0.15 throughout – so for every dollar of national income earned 15 cents is taken out in tax.

- The marginal propensity to consume is 0.8 – so for every dollar of disposable income 80 cents is consumed and 20 cents is saved.

- The marginal propensity to import is 0.2 – so for every dollar of national income (Y) 20 cents is lost from the expenditure stream into imports.

You might want to right-click the images to bring them up into a separate window and the print them (on recycled paper) to make it easier to follow the evolution of this economy over the 10 periods shown.

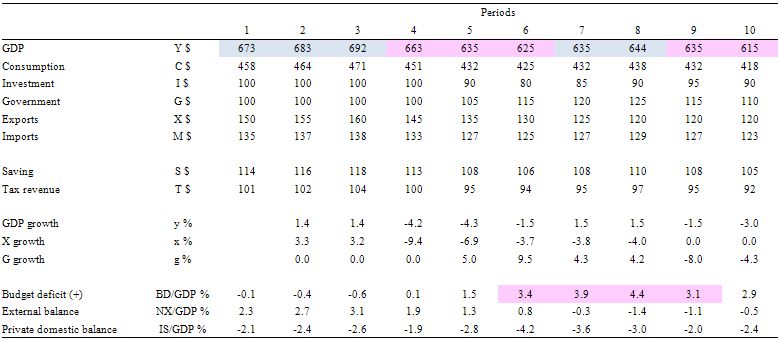

The next table quantifies the ten-period cycle and the graph below it presents the same information graphically for those who prefer pictures to numbers. The description of events is in between the table and the graph for those who do not want to print.

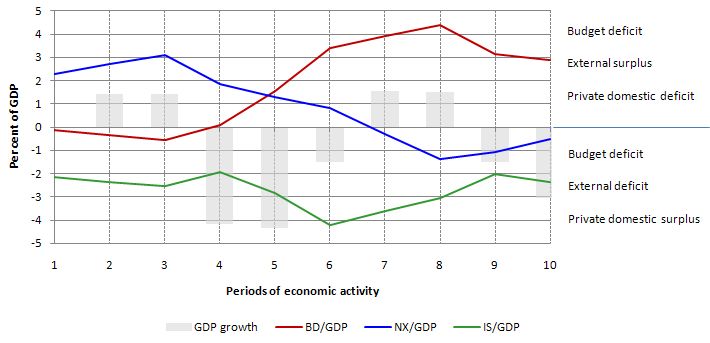

The graph below shows the sectoral balances – budget deficit (red line), external balance (blue line) and private domestic balance (green line) over the 10-period cycle as a percentage of GDP (Y) in addition to the period-by-period GDP growth (y) in percentage terms (grey bars).

Above the zero line means positive GDP growth, a budget deficit (G > T), an external surplus (X > M) and a private domestic deficit (I > S) and vice-versa for below the zero line.

This is an economy that is enjoying steady GDP growth (1.4 per cent) courtesy of a strong and growing export sector (surpluses in each of the first three periods). It is able to maintain strong growth via the export sector which permits a budget surplus (in each of the first three periods) and the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earning.

The budget parameters (and by implication the public debt ratio) is well within the Maastricht rules and not preventing strong (full employment growth) from occurring. You might say this is a downward bias but from in terms of an understanding of functional finance it just means that the government sector is achieving its goals (full employment) and presumably enough services and public infrastructure while being swamped with tax revenue as a result of the strong export sector.

Then in Period 4, there is a global recession and export markets deteriorate up and governments delay any fiscal stimulus. GDP growth plunges and the private domestic balance moves towards deficit. Total tax revenue falls and the budget deficit moves into balance all due to the automatic stabilisers. There has been no discretionary change in fiscal policy.

In Period 5, we see investment expectations turn sour as a reaction to the declining consumption from Period 4 and the lost export markets. Exports continue to decline and the external balance moves towards deficit (with some offset from the declining imports as a result of lost national income). Together GDP growth falls further and we have a technical recession (two consecutive periods of negative GDP growth).

With unemployment now rising (by implication) the government reacts by increasing government spending and the budget moves into deficit but still within the Maastricht rules. Taxation revenue continues to fall. So the increase in the deficit is partly due to the automatic stabilisers and partly because discretionary fiscal policy is now expanding.

Period 6, exports and investment spending decline further and the government now senses a crisis is on their hands and they accelerate government spending. This starts to reduce the negative GDP growth but pushes the deficit beyond the Maastricht limits of 3 per cent of GDP. Note the rising deficits allows for an improvement in the private domestic balance, although that is also due to the falling investment.

In Period 7, even though exports continue to decline (and the external balance moves into deficit), investors feel more confident given the economy is being supported by growth in the deficit which has arrested the recession. We see a return to positive GDP growth in this period and by implication rising employment, falling unemployment and better times. But the deficit is now well beyond the Maastricht rules and rising even further.

In Period 8, exports decline further but the domestic recovery is well under way supported by the stimulus package and improving investment. We now have an external deficit, rising budget deficit (4.4 per cent of GDP) and rising investment and consumption.

At this point the EMU bosses take over and tell the country that it has to implement an austerity package to get their fiscal parameters back inside the Maastricht rules. So in Period 9, even though investment continues to grow (on past expectations of continued growth in GDP) and the export rout is now stabilised, we see negative GDP growth as government spending is savaged to fit the austerity package agree with the EMU bosses. Net exports moves towards surplus because of the plunge in imports.

Finally, in period 10 the EMU bosses are happy in their warm cosy offices in Brussels or Frankfurt or wherever they have their secure, well-paid jobs because the budget deficit is now back inside the Maastricht rules (2.9 per cent of GDP). Pity about the economy – it is back in a technical recession (a double-dip). Investment spending has now declined again courtesy of last period’s stimulus withdrawal, consumption is falling, government support of saving is in decline, and we would see employment growth falling and unemployment rising.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 4:

It is clear that EMU nations cannot use the exchange rate mechanism to adjust for trading imbalances arising from a lack of competitiveness within the Eurozone. With fiscal and monetary policy tied by the EMU arrangements, the only adjustment mechanism left is to reduce wages and prices to restore competitiveness. While harsh this will ultimately improve the competitive position of Greece, Portugal, Ireland and other nations currently in external deficit.

The answer is False.

The temptation is to accept the rhetoric after understanding the constraints that the EMU places on member countries and conclude that the only way that competitiveness can be restored is to cut wages and prices. That is what the dominant theme emerging from the public debate is telling us.

However, deflating an economy under these circumstance is only part of the story and does not guarantee that a nations competitiveness will be increased.

We have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative. Their English-language services are becoming better by the year.

Nominal exchange rate (e)

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. There are two ways in which we can quote a bi-lateral exchange rate. Consider the relationship between the $A and the $US.

- The amount of Australian currency that is necessary to purchase one unit of the US currency ($US1) can be expressed. In this case, the $US is the (one unit) reference currency and the other currency is expressed in terms of how much of it is required to buy one unit of the reference currency. So $A1.60 = $US1 means that it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US.

- Alternatively, e can be defined as the amount of US dollars that one unit of Australian currency will buy ($A1). In this case, the $A is the reference currency. So, in the example above, this is written as $US0.625= $A1. Thus if it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US, then 62.5 cents US buys one $A. (i) is just the inverse of (ii), and vice-versa.

So to understand exchange rate quotations you must know which is the reference currency. In the remaining I use the first convention so e is the amount of $A which is required to buy one unit of the foreign currency.

International competitiveness

Are Australian goods and services becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas? To answer the question we need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign).

Clearly within the EMU, the nominal exchange rate is fixed between nations so the changes in competitiveness all come down to the second source and here foreign means other nations within the EMU as well as nations beyond the EMU.

There are also non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

We can define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate, and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise. An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect.

But this option is not available to an EMU nation so the only way goods in say Greece can become cheaper relative to goods in say, Germany is for the relative price ratio (Pw/P) to change:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively cheaper within the EMU; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively more expensive within the EMU.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

The real exchange rate

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to tell us about movements in relative competitiveness. The real exchange rate captures the overall impact of these variables and is used to measure our competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P) (2)

where P is the domestic price level specified in $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60. In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, ie 28%.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase our exports and reduce our imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

In the case of the EMU nation we have to consider what factors will drive Pw/P up and increase the competitive of a particular nation.

If prices are set on unit labour costs, then the way to decrease the price level relative to the rest of the world is to reduce unit labour costs faster than everywhere else.

Unit labour costs are defined as cost per unit of output and are thus ratios of wage (and other costs) to output. If labour costs are dominant (we can ignore other costs for the moment) so total labour costs are the wage rate times total employment = w.L. Real output is Y.

So unit labour costs (ULC) = w.L/Y.

L/Y is the inverse of labour productivity(LP) so ULCs can be expressed as the w/(Y/L) = w/LP.

So if the rate of growth in wages is faster than labour productivity growth then ULCs rise and vice-versa. So one way of cutting ULCs is to cut wage levels which is what the austerity programs in the EMU nations (Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc) are attempting to do.

But LP is not constant. If morale falls, sabotage rises, absenteeism rises and overall investment falls in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts then productivity is likely to fall as well. Thus there is no guarantee that ULCs will fall by any significant amount.

Question 5:

If the US budget deficit keeps rising to meet the need for more fiscal stimulus, it would have to bear the political costs of a rising public debt ratio. This is one of the reasons the US government is talking about reducing net spending.

The answer is False.

Again, this question requires a careful reading and a careful association of concepts to make sure they are commensurate. There are two concepts that are central to the question: (a) a rising budget deficit – which is a flow and not scaled by GDP in this case; and (b) a rising public debt ratio which by construction (as a ratio) is scaled by GDP.

So the two concepts are not commensurate although they are related in some way.

A rising budget deficit does not necessary lead to a rising public debt ratio. You might like to refresh your understanding of these concepts by reading this blog – Saturday Quiz – March 6, 2010 – answers and discussion.

While the mainstream macroeconomics thinks that a sovereign government is revenue-constrained and is subject to the government budget constraint, MMT places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue.

However, the framework that the mainstream use to illustrate their erroneous belief in the government budget constraint is just an accounting statement that links relevant stocks and flows.

The mainstream framework for analysing the so-called “financing” choices faced by a government (taxation, debt-issuance, money creation) is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

Remember, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

For the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

That interpretation is inapplicable (and wrong) when applied to a sovereign government that issues its own currency.

But the accounting relationship can be manipulated to provide an expression linking deficits and changes in the public debt ratio.

The following equation expresses the relationships above as proportions of GDP:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP. A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

So a nation running a primary deficit can obviously reduce its public debt ratio over time. Further, you can see that even with a rising primary deficit, if output growth (g) is sufficiently greater than the real interest rate (r) then the debt ratio can fall from its value last period.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Hey guys, sorry about the length but there are a few things I cannot get my head around.

I’m a bit confused regarding the institutional arrangements between the treasury and Central bank in various countries (e.g. Australia and America). If anyone could answer the following questions it would be a big help?

1. The general line that I have read in the literature is that, ‘when governments spend they credit bank accounts’. If the Treasury is deficit spending, is there an account besides the treasury’s main account which is in the negative?

2. As I understand it, in America, the Treasury has to maintain a closing balance of $5 billion (each night?) in its main account. Is this the main account in which the Federal Reserve draws down when the Treasury spends?

3. What happens if the treasury is exceptionally below this target and at the same time, the Federal Reserve has achieved its desired level of reserves? Would this rule out the ability of the Treasury to withdraw ‘funds’ away from its Tax and Loan accounts? Would the Federal Reserve create another account to assist in the Treasury achieving the $5 billion target?

4. While reading through some papers from the RBA, it seems as though the RBA is under the impression that the Government needs a positive balance in its main account before it can spend, as the following indicates:

There are a few points here: Firstly, there is an implicit acknowledgement that the main concern of Government spending is its impact upon system liquidity and therefore the interbank settlement.

Secondly, and this is the main issue that I don’t understand, there is a requirement that the Government’s ‘core’ account have sufficient funds prior to spending. I imagine that perhaps the following operations would be performed: firstly, perhaps there is a similar institutional arrangement in Australia, like the American ‘Tax and Loan accounts’, which the Government would call upon to increase ‘funds’ in its ‘core account’ to a desired level -ignoring the possibility that the RBA would have to offset the reserve (exchange settlement) drain. Secondly, perhaps there are several accounts which the treasury has with the RBA that would be called upon or created to inject ‘funds’ into the ‘core account’. Either way, doesn’t the fact that RBA requires the Government’s core account to have funds a sort of ‘fiscal discipline’?

5. Could it be the case that the treasury is required to first source funds through taxation and maintain a certain sized account before a central bank would allow spending? Obviously such an arrangement would be pointless as during this process of increasing ‘funds’ in the core account, the central bank would be offsetting the reserve drain.

6. It seems that ‘theoretically’ the central bank could constrain government spending by allowing treasury cheques to bounce. But of course, such a move would be disastrous for the entire economy (I think).

—-

Whilst reading through the RBA papers I found the following: Implications for the Reserve Bank’s Liquidity Management operations of Changes in Commonwealth Government Cash Flows (2000). If the name wasn’t enough to give it away, the paper provides an insight into the various arrangements that the RBA and Treasury have created to ensure that any potential reserve effects from the new tax arrangements would have a reduced ‘reserve effect’. For example, discussion changes were made to the maturity of ‘Treasury notes’, so that the notes would mature on the major tax dates. The RBA justified this stating:

There is also the following quote from another RBA paper:

—–

Sources:

Hart, N. XXXX. Discretionary Fiscal policy and Budget Deficits: An ‘Orthodox’ Critique of Current Policy Debate. The Economic and Labour relations Review. Vol. 19 no. 2 pp. 39-58.

RBA, 2000. Implications for the Reserve Bank’s Liquidity Management operations of Changes in Commonwealth Government Cash Flows. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin. August 2000. Pp. 50-55

RBA, 2001. ‘The movement of interest rates’, Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, October 12-18.

RBA, 2009. The RBA’s role in processing the Fiscal Stimulus Payments. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin. August 2009.

Hi Bill,

The NCB can indirectly purchase government bonds in an immoral-but-legal way. An NCB’s acquisition of government bonds at an auction can utmost match maturing holdings. The workaround is that the NCB can set-up a kind of (multiple) transaction(s) where an “eligible counterparty” can be lent funds for collateral. The counterparty can then use these funds to purchase government bonds at the auction and sell it to the NCB. So, the first leg is funds for collateral, the second leg is collateral for securities – slightly different from a repurchase agreement.

The NCB faces no issues as far as the ECB is concerned, because the ECB is not involved in this transaction as the NCBs are fully allowed to expand their balance sheets. The only question here is that of politics. The ECB may not like these things but it is totally legal. It doesn’t violate the Article 21.1 of the PROTOCOL ON THE STATUTE OF THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM OF CENTRAL BANKS AND OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK which says

Looks like you’re making progress, Ramanan.

So the overdraft prohibition regarding each central government and its NCB is essentially the same as that of the US treasury with the Fed?

Do EZ central governments spend by crediting bank accounts?

🙂

Yes JKH – its the same – crediting bank accounts. In fact one can even say that “The funds to purchase government securities and pay taxes come from the government itself” for the countries which are using the Euro.

The short term rate is completely at the control of the NCBs and the ECB according to me because of unlimited and uncollateralized credit facility amongst the ECB and the NCBs. The rate is decided by the ECB. (I would actually consider the NCBs and the ECB as one entity just like the CB and the Treasury are considered as one unit in this blog.) It is the long end of the curve which is problematic. Plus the rules of the Maastricht Treaty but some countries have already broken them!

The US Fed and the Treasury can play this game: If they are uncomfortable with yields increasing at the long end, they can move the auctions at the short end. The demand-supply at the long end will put a cap on the yields. If that doesn’t work, the Fed can purchase government debt from the markets. The NCBs on the other hand do not have any such flexibility and a current account deficit will lead to a leakage and lesser funds to purchase government debt causing the yields to move up in one direction causing all sorts of discomfort.

So the only difference I see is in the medium/long term bonds – though that is a big difference. However, the NCBs can play some games.

Btw, there is another way the US Treasury can “finance” its spending. The Treasury has accounts at the banks and according to Z.1, it was around ? $B30-ish in late 2000s. (Of course, banks would have sold them later) The EZ governments can in principle place the debt directly with the banks. However, there is some rule which prevents that in the EZ- something like banks can only purchase government bonds using reserves and not through deposit creation.

The big difference with US treasuries is credit ratings, including on the short-end, and–if my understanding is correct–that the Euro NCB’s are not allowed to buy securities below a certain rating.

Surely each NCB is allowed to buy the securities of its own government (from the market) without credit rating restrictions?

Went and looked at the discussion I was referring to (private email). Got my facts a bit mixed up, as there wasn’t anything about credit quality of NCB purchases–it would stand to reason that there are some limits, as even the Fed has limits in that regard (though it can get around them if it declares itself there is a crisis for which it needs to expand the range and quality of its purchases), but I haven’t read any specifics (haven’t looked, really, but haven’t seen anything). First, the NCB purchases or loans can’t exceed the demand for rbs–and if they do, they’ll have to be offset somewhere else by selling another asset. So, in order to add more Greek Tsy’s than are maturing, the NCB would have to be unloading other assets. Second, any counterparty as in Ramanan’s point may have their own limitations to the credit ratings of bonds they hold/purchase. Greek banks, for instance, certainly do (and would run the risk of having their collateral marked down), though others obviously do not. Warren’s noted several times that Greek banks were financing Greek govt debt, “but this conduit can be shut down at any time by a series of bank failures.”

An interesting question is whether NCBs return profits to the national treasuries.

JKH,

From what I read in ECB documents, for some reason, the larger Governments (think Germany and France) can self-certify their debt as elligible collateral, but the smaller ones (like Greece) actually have to get Moody’s and the others to sign off.

This seems like another unfair procedure against the smaller countries. Resp,

Scott,

You may find this interesting. It says something like distribution of profits should not look like it is helping out the Treasury or something similar.

OPINION OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK of 2 December 2008 at the request of the Spanish State Secretary for Economic Affairs on a draft royal decree on the arrangements for paying the Banco de España’s profits to the Treasury (CON/2008/82)

There is a Godley-Lavoie paper/model on the Euro Zone where they assume that the profits are distributed.

Scott,

I have a point regarding the NCB purchase. Let us assume they purchase in the secondary markets and there are no restrictions. They can purchase upto the point where there is a balance of payments without causing issues with the monetary policy. A negative balance of payments will cause a drain in reserves. The NCB can offset this by purchasing its country’s government bonds. So there is a possibility of some purchases without affecting the monetary policy.

Scott,

“An interesting question is whether NCBs return profits to the national treasuries.”

This is from the Irish Central Bank Annual report for 2008 which returned After retained earnings, a surplus income of €290.1 million paid to the Exchequer.

http://www.centralbank.ie/data/AnnRepFiles/2008%20Annual%20Report%20-%20Rev%2017%20July%2009.pdf

Ramanan . . . they have to hit the overnight target given that the target rate is above the remuneration rate, so every add not consistent with the daily (or, in EMU case, maintenance period) demand for reserve balances must be offset. That’s the criteria for OMO, not the BOP. Remember when Warren discussed the ECB’s $500B add that wasn’t? Because the NCB’s had to sterilize it that day to hit the target rate.

Scott,

Yes there is no direct connection superficially but any cross border payment causes the reserves to go down/up. What I am saying is: let us say that Greece imports $1m of German machines, a payment through TARGET2 will have Greece’s banks seeing their reserves level go down by $1m, putting an upward pressure on the rate at which Greece banks are lending each other. The NCB can simply offset this by buying $1m of Greece bonds putting the reserves level back at where it was – before the imports.

The movement of upward movement of long term yields is essentially a consequence of a current account deficit. If, during a month, the government deficit is DEF, the wealth increase of Greece agents is DEF as well assuming a zero current account deficit. If the current account is in deficit, that would mean that there is less for Greece agents to purchase Greek bonds and will cause the Greece yields to move up because of supply-demand mismatch.

Scott,

Are you saying the Eurozone currently has no structural excess reserve position comparable to the Fed?

i.e. a system excess created by “credit easing” comparable to the Fed?

i.e. a compensated excess reserve position, distributed across EZone NCB’s?

i.e. whereby interest rate management is separable from reserve quantities?

Interesting article on ECB excess reserves I found here from Roubini.

Ignoring the mention of the money multiplier, there’s an intriguing reference to the apparent structure of excess reserves being made up of two components – “pure” and “the deposit facility”. The deposit facility contains the lion’s share of the excess, and interest is paid. My guess is that “pure” reserves are the noise that doesn’t get properly allocated to the deposit facility and therefore isn’t compensated.

“The second case where the money multiplier doesn’t work or works only partially is when the central bank pays an interest on excess reserves. When reserves are remunerated, the process stops sooner, how sooner depends on the rate itself. Indeed, in this case, the process stops when the market rate reaches the level at which banks’ reserves are remunerated. If the central bank remunerates reserves at the same level of its target rate, then the money multiplier disappears. In the ECB operational framework, excess reserves almost completely consist of the deposit facility (in August “pure” excess reserves were EUR 900mn whereas the deposit facility averaged EUR 160bn) which is remunerated. …. Hence, beyond the precautionary motive that currently leads banks to deposit large sums at the ECB, it has to be saidthat the central bank’s operational framework has always prevented the money multiplier effect from being fully operational. Plus, it may appear redundant, but it has to be remembered that the current very large excess reserves of the Eurosystem were not created with the goal of lowering the short-term interest rate or increasing bank lending significantly to pre-crisis levels. Certainly, the ECB has prevented a full-fledged credit crunch and the fact that growth in lending to the private sector remains positive has to be considered a great achievement. These reserves have to be considered mainly a byproduct of the lending policies designated by the ECB to face market disruptions. Hence, no surprise that the money multiplier is not working.”

The money multiplier reference, however erroneous, is not important. The rest of it makes sense, and strikes me as exactly analogous to the excess reserve setting created by the Fed through its credit easing programs.

BTW, the excess reserves are held at the NCBs. It strikes me also that the ECB terminology is typically highly misleading in terms of implied operational meaning. People should usually be speaking of the system – the ESCB – and not the ECB.

http://www.roubini.com/euro-monitor/257720/the_ecb_s_deposit_facility_and_its_guard_against_inflation_-_euro_thoughts_sep__21-25__2009_-_unicredit_group

Thank you Bill for these AWESOME quizzes. (I print out your answers for careful study…)

Do you have a favorite (introductory?) textbook(s) for those of us who aren’t exactly acing your quizzes (er, i’m thinking of myself!), who would to improve the foundation without requiring a lifetime’s devotion; e.g., Mankiw’s MacroEcon … ? Thanks!

Dear Ramanan

You noted:

Then you quoted the famous Article 101.1 of the consolidated Treaty, which has been interpreted as applying to activity in the primary bond markets and not the secondary markets. So NCBs are not allowed to lend to their governments directly or buy government debt directly. That is clear.

It is also true that they can purchase the debt in the secondary markets if the government can issue its debt in the first place. So it doesn’t even have to be as sneaky as you suggest. The NCB has the right to purchase debt and does so often.

But it is not just a question of politics as you suggest that they would not do this infinitely. While the NCBs can extend loans under certain conditions and therefore increase the monetary base, they are legally obliged to work within the Euro system charters to target price stability and so that process is finite.

Further, similar to the US or Australian system (or most other systems) it is ultimately the Treasury in the EMU system that will guarantees the NCB will not become insolvent. All risk in the EMU is pushed down to the national level. The ECB carries no responsibility for losses made by the NCBs. However there is a major difference between the US/Australian system and the EMU – the central bank carries no credit risk in buying government debt in the former cases but is exposed to credit risk in the EMU because its ultimate guarantor can go broke if it is unable to continue financing its operations. So a central bank will be reluctant to enter a partnership (via the secondary markets) to keep buying the debt of a government which is under solvency pressure.

After all, the EMU rendered these banks the most independent of all central banks.

So yes they can expand their balance sheets by buying assets in the secondary markets which keeps them inside the rules related to Article 101 but that process is finite and may not be sufficient to save a national government from default. That is the major difference between a sovereign monetary system and the EMU.

best wishes

bill

Thanks for the reply Bill. Makes sense. I was merely trying to understand some peculiarities of the system. Clearly it is nowhere close to having a sovereign system.

Hi Ramanan,

“The NCB can simply offset this by buying $1m of Greece bonds putting the reserves level back at where it was – before the imports. ”

This link here states: “Concerning the total trade of member states, the largest surplus was observed in Germany (+135.8 billion euro in 2009), followed by the Netherlands (+37.9 billion euro), Ireland (+37.4 billion euro) and Belgium (+12.8 billion euro).

The United Kingdom (-92.6 billion euro) registered the largest deficit, followed by France (-54.5 billion euro), Spain (-49.5 billion euro), Greece (-28.5 billion euro) and Portugal (-19 billion euro). ”

So if the Greek NCB wants to replace/provide reserves equal to this 28.5B trade deficit (assuming it is all intra EMU), and the preferred asset purchase is Greek Treasuries, would not in a round about way, Greece would have to task its Treasury to net issue +28.5B, get their GREEK (not foreign) Dealers to buy it, and then Greek NCB purchase this 28.5B from the same Greek PDs to maintain reserves in Greek system. I think this +28.5B of net issuance blows away the 3% Mastrcit limit, just for monetary operations (not for “sleeping in late”), how can they comply? Resp.

Ramanan,

Any further thoughts on the accounting for a $ 1 trillion Euro drop?

Matt,

Maybe they buy up existing debt. But the general question of current account effects on NCB reserve distribution is an interesting one.

Both,

I still find the entire subject to be an opaque mystery from what I’ve read (elsewhere) so far.

JKH,

Per your original question wrt helo drops are fiscal, it would seem they would have to issue per capita bonds to drain the drop per Scott F blog on this topic. Perhaps special series bonds.

Perhaps they could also let countries subtract intra EMU trade deficits from fiscal deficits for Mastrict purposes. You know if Greece could subtract the 28.5B from the 40B (i think) they are goint to net issue this year they would be real close the the 3% per year limit right now. (This would be fiscal deficit net of issuance due to monetary operations?)

I think you have more insight into this mystery than Roubini it seems!, Resp,

A very slightly off-topic question relating to Q.3 and more particularly the 20th March quiz, to all the experts who understand sectoral balances…

The UN have a very comprehensive economics database with information on most (?) countries. So far I\’ve not been able to work out which items correspond to those listed in Bill\’s sectoral balance equation ( I-S + G-T + X-M = 0). In particular, I\’m not sure which values I should read for savings and investment. Does anyone know? Thanks in advance for any help you can offer.

dnm

Matt,

Apart from the “drop”, it just occurred to me reading a 2009 speech by Trichet that the Euro zone NCB deposit facility(s) is not classified as a reserve position, even though it is quite analogous to the excess reserve position at the Fed.

If so, it would explain some of my personal confusion in comparing the two systems. If not, I remain at sea on this part as well.

Also, as per my previous comment, Trichet in the same speech refers liberally to Eurosystem operations rather than ECB operations:

“These measures, which reflect the very significant strengthening of the Eurosystem’s intermediation role during this period of turbulence, have allowed solvent banks continued access to liquidity despite the dysfunctional nature of the money market. They have also helped to alleviate the tensions observed in certain sectors of the money market. For example, the spread between unsecured longer-term EURIBOR rates and the rates on overnight index swaps has declined considerably – although it remains elevated, significantly higher than the levels observed prior to September 2008. In practice, these measures allow euro area banks to obtain as much euro liquidity as they wish, whether through our weekly operations or our longer-term refinancing operations, using a wide range of assets as collateral.

In total, the Eurosystem’s balance sheet rose by about EUR 600 billion since end-June 2007 and today, an increase of about 65%; with the assets reflecting the strong increase in the volume of liquidity provided and the liabilities reflecting banks’ concomitant recourse to the deposit facility. These measures have proved effective in overcoming the liquidity shortage in the interbank market. However, they cannot eliminate the increased concerns regarding credit risk. In this regard, the conditions in the money aversion. The increase in the Eurosystem’s intermediation role has proved necessary in response to the current dysfunctional nature of the money market, but this cannot – and must not – be regarded as anything other than a temporary measure. The Eurosystem wishes, of course, to see a return to interbank lending and traditional intermediation activity by banks. The ECB’s recent decision to return to 200 basis points the corridor formed by the interest rates on the standing facilities either side of the rate on the main refinancing operations aims to stimulate interbank activity. In this respect, we are observing a reduction in banks’ demand for refinancing in our open market operations and a correlated decline in recourse to the deposit facility.”

I’m starting to think of the NCBs as a group of New York Feds, at least at the operational level.

It seems strange that an NCB would be constrained in OMO by the credit quality of its corresponding nation.

Matt,

I was merely talking of current account between the Euro nations, assuming that the rest of the world didn’t exist! The current account deficit and the government deficit are related by an identity. Also, the countries have already broken the Maastricht Treaty rules. I need to know the accounting related to “fines”. So the connection between reserves and the current account was a mere curiosity.

JKH,

Even I see the NCBs as a group of NYFeds. In fact I consider the NCBS plus the ECB as one unit FMPP – for most practical purposes. The NCBs seem like puppets of the ECB.

I read somewhere that the ECB takes the FX assets on its books. Plus I don’t yet know why the ECB monetary policy documents include the FX related transactions. Of course the Fed also considers dealing in FX as a part of OMO but doesn’t give much importance. (which the exception of FX swaps in recent times)

The accounting entry related to the $1T drop seems ok to me – the ECB instructs the NCBs to buy the government debt if the Greek NCB buys €1b from the Greek treasury, its €1b on the Bank of Greece’s assets and €1b liabilities to the Greek Treasury. The Treasury can then spend by crediting bank accounts.

However, the Bank of Greece will find itself difficult to achieve targeting short term rates and overnight rates will fall to 0.25% – the “deposit facility”. So the ECB may have to do some modifications.

Ramanan,

Even you?

So given that the ECB has no direct fiscal operational authority, and NCBs aren’t allowed to acquire debt directly from their Treasuries, the 1T proposal assumes a complete uprooting of the existing system and legal framework.

It requires dissolution of the Euro system. Seems to me that’s as important than the 1T proposal per se.

Ramanan,

The reserve distribution problem applies in the case of purely gross capital flows across borders as well, apart from current account flows and their offsetting capital account flows.

Ramanan,

I think that 28.5B trade deficit may be pretty close to what Greece is doing with the rest of the Eurozone. here is a link to Bank of Greece site on Trade (you again get a un/pw challenge but just dont enter anything and keep hitting enter and the .xls file eventually opens). US trade surplus w/ Greece is only $1B

I think what you have posted is significant, no? If Greece has a 20B+ trade deficit with Eurozone, then they may have to violate Mastrict just to do normal monetary operations….while being accused of “cheating” because of it. If they buy Greek on the run govt bonds from a holder in France it doesnt help them increase reserves in Greece system. I could be over playing your observation as I never thoght of it that way before you posted it….Resp,

“Et tu JKH?” Shakespeare now!? I agree the helo drop is a big departure. Perhaps if ESCB Treasuries issued special series EMU wide govt debt securities call them “EMU Fiscal Stabilization Bonds” or something, that didnt count against Mastrict and govts issued on a per-capita basis like Warren M advocates for…Resp,

JKH,

The ECB may enter the markets if it thinks its needed – thats what the monetary policy document says.

As far as the legal framework is concerned, I think they can easily find some workaround – “sneaking in” as Bill would put it. Yes the capital flows can have reserve effects as well 🙁 but that may be good or bad – a capital outflow (say out of some other Greek asset, not government debt) will allow the Bank of Greece to purchase more Greek bonds!

Ramanan,

I bet if you looked into it they would “enter” by delegating the operation to an NCB(s)., Resp,

The ECB may enter the market for monetary policy – not straight out fiscal policy.

Matt,

You are quite right

JKH,

I think the EZ does not have this mechanism which has to do with currency sovereignity one way or the other:

Let us consider the US economy – closed for simplicity. Let us assume that the Treasury issues two kinds of securities. Bills and Bonds. The first is a short term say with 3m maturity and the Bonds are perpetuities. The assumption is that the US has been issuing these perpetuities since the beginning of the world and pays $1 every quarter for each security. Instead of issuing new CUSIPS for long term the Treasury just issues more securities with the same CUSIP. I assume the private sector consisits of households, production firms, banks, the Fed and the Treasury. In this simplified economy, households purchase all the debt issued by the Treasury. They make allotment based on their liquidity preferences. I ignore equities and corporate debt as well for simplicity. Households have 3 choices to make – deposits, bills and bonds. The central bank holds the bills only and the $-value is equal to the liabilities – the reserves with banks. The complication is that households allot their wealth based on expected income and wealth in the period, not actual. The Fed fixes the short term rates and the Treasury lets the perpetuity yield (and hence price) move between a band.

The Fed and the Treasury supply whatever is demanded by households as far as Bills are concerned. There is no market clearing. The price has been fixed by the Fed. Hence the demand-supply is : supply = whatever is demanded. The yield of the perpetuity is let go in one direction because the Fed and the Treasury do not know the household liquidity preferences. The household demand functions for deposits (zero-yield), bills and bonds depend on their accumulated wealth, expectations of income, the rate on bills, the expected return on bonds. Now, these things completely fix the amounts alloted in the assets. Once the yields go out of the band, the Fed/Treasury know that they can issue more bills. The demand for Bills will be higher, because household think that the price of the perpetuity will drop further and they want to hold more bills. So supply them more bills. This will cause less perpetuities to be issued and the demand-supply at the long end will bring back the yields to lower levels.

Now let us take the case of the EZ and assume that there are just two countries – Greece and Germany. Let us assume that the governments issue just bills and bonds. The short term rates are fixed by the ECB. Let us assume that the NCBs are just puppets. One thing is that the Greek and the German Treasuries have to work in isolation without the help of the the Bank of Greece or Deutsche Bundesbank or the ECB but let us assume that it is not problematic. Simply by accounting one country runs a current acount deficit. There is a leakage. This means that one country (say Greece) has households with lesser wealth and income to purchase the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement. Recession arrives. Faced with a downturn, the expection of income of Greek households is also going to go down. The Greece Treasury has to allot bills such that supply < demand and the remaining in bonds. The Greek debt can also be purchased by the German households – but their liquidity preferences for Greek debt are lesser than the Greek households. The detioration leads to the Greek Treasury move the top of the band even higher, something which the US Treasury need not do. The cause for moving the top of the band is the leakage due to the current account deficit and of course lower expectations of income by households. The rating agencies passing their judgements makes the case even worse. However, the problems arise even if there are no rating agencies. Devaluation is not a choice. (Even in the gold standard, devaluation wouldn't help but calls for another discussion!) The only way is to go into austerity – decrease government spending and increase tax rates. The German household preferences may help a bit but I guess at very high yields only. This leads to a fall in output and employment and there is no mechanism to come back to the original output.

Godley & Lavoie make such stories with some neat math.

Ramanan,

I d bet that Greece trade deficit with rest of EMU is 20B+. I think you have shown how the Bank of Greece/Greek Treasury just conducting normal/reqired monetary policy in this environment creates a serious Mastrict violation thru no fault. Do you think anyone in Greece knows this? they seem to be blaming CDS…Resp,