Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 6, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

In the current macroeconomic debate, considerable attention is being focused on the public debt to GDP ratio with some mainstream economists claiming that a ratio of 80 per cent is a dangerous threshold that should not be passed. They therefore advocate that governments run primary surpluses (taxation revenue in excess of non-interest government spending) to start reducing the debt ratio. Modern monetary theory tells us that while a currency-issuing government running a deficit can never reduce the debt ratio it doesn’t matter anyway because such a government faces no risk of insolvency.

The answer is False.

While Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue, the mainstream debate is dominated by the concept.

The unnecessary practice of fiat currency-issuing governments of issuing public debt $-for-$ to match public net spending (deficits) ensures that the debt levels will rise when there are deficits.

Rising deficits usually mean declining economic activity (especially if there is no evidence of accelerating inflation) which suggests that the debt/GDP ratio may be rising because the denominator is also likely to be falling or rising below trend.

Further, historical experience tells us that when economic growth resumes after a major recession, during which the public debt ratio can rise sharply, the latter always declines again.

It is this endogenous nature of the ratio that suggests it is far more important to focus on the underlying economic problems which the public debt ratio just mirrors.

Mainstream economics starts with the flawed analogy between the household and the sovereign government such that any excess in government spending over taxation receipts has to be “financed” in two ways: (a) by borrowing from the public; and/or (b) by “printing money”.

Neither characterisation is remotely representative of what happens in the real world in terms of the operations that define transactions between the government and non-government sector.

Further, the basic analogy is flawed at its most elemental level. The household must work out the financing before it can spend. The household cannot spend first. The government can spend first and ultimately does not have to worry about financing such expenditure.

However, in mainstream (dream) land, the framework for analysing these so-called “financing” choices is called the government budget constraint (GBC). The GBC says that the budget deficit in year t is equal to the change in government debt over year t plus the change in high powered money over year t. So in mathematical terms it is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

However, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

But for the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

Further, in mainstream economics, money creation is erroneously depicted as the government asking the central bank to buy treasury bonds which the central bank in return then prints money. The government then spends this money. This is called debt monetisation and you can find out why this is typically not a viable option for a central bank by reading the Deficits 101 suite – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Anyway, the mainstream claims that if governments increase the money growth rate (they erroneously call this “printing money”) the extra spending will cause accelerating inflation because there will be “too much money chasing too few goods”! Of-course, we know that proposition to be generally preposterous because economies that are constrained by deficient demand (defined as demand below the full employment level) respond to nominal demand increases by expanding real output rather than prices. There is an extensive literature pointing to this result.

So when governments are expanding deficits to offset a collapse in private spending, there is plenty of spare capacity available to ensure output rather than inflation increases.

But not to be daunted by the “facts”, the mainstream claim that because inflation is inevitable if “printing money” occurs, it is unwise to use this option to “finance” net public spending.

Hence they say as a better (but still poor) solution, governments should use debt issuance to “finance” their deficits. Thy also claim this is a poor option because in the short-term it is alleged to increase interest rates and in the longer-term is results in higher future tax rates because the debt has to be “paid back”.

Neither proposition bears scrutiny – you can read these blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for further discussion on these points.

The mainstream textbooks are full of elaborate models of debt pay-back, debt stabilisation etc which all claim (falsely) to “prove” that the legacy of past deficits is higher debt and to stabilise the debt, the government must eliminate the deficit which means it must then run a primary surplus equal to interest payments on the existing debt.

A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

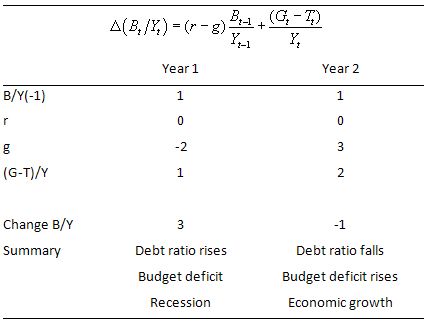

The standard mainstream framework, which even the so-called progressives (deficit-doves) use, focuses on the ratio of debt to GDP rather than the level of debt per se. The following equation captures the approach:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

This standard mainstream framework is used to highlight the dangers of running deficits. But even progressives (not me) use it in a perverse way to justify deficits in a downturn balanced by surpluses in the upturn.

The question notes that “some mainstream economists” claim that a ratio of 80 per cent is a dangerous threshold that should not be passed – this is the Reinhart and Rogoff story.

Many mainstream economists and a fair number of so-called progressive economists say that governments should as some point in the business cycle run primary surpluses (taxation revenue in excess of non-interest government spending) to start reducing the debt ratio back to “safe” territory.

Almost all the media commentators that you read on this topic take it for granted that the only way to reduce the public debt ratio is to run primary surpluses. That is what the whole “credible exit strategy” hoopla is about.

Further, there is no analytical definition ever provided of what safe is and fiscal rules such as those imposed on the Eurozone nations by the Stability and Growth Pact (a maximum public debt ratio of 60 per cent) are totally arbitrary and without any foundation at all. Just numbers plucked out of the air by those who do not understand the monetary system.

But the specific question you had to respond to (TRUE/FALSE) after some background information was:

Modern monetary theory tells us that while a currency-issuing government running a deficit can never reduce the debt ratio it doesn’t matter anyway because such a government faces no risk of insolvency.

MMT does not tell us that a currency-issuing government running a deficit can never reduce the debt ratio. That was the falsehood that made the correct answer false. The other part of that sentence is true but was designed to lull you into incorrect analytical thinking.

The standard formula above can easily demonstrate that a nation running a primary deficit can reduce its public debt ratio over time.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

Here is why that is the case.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

The orthodox economists use this analysis to argue that permanent deficits are bad because the financial markets will “penalise” a government living on debt. If the public debt ratio is “too high” (whatever that is or means), markets “lose faith” in the government.

To make matters simple, assume a public debt ratio at the start of the period of 100 per cent (so B/Y(-1) = 1) and a current real interest rate (r) of 3 per cent. Assume that GDP is growing (g) at 2 per cent. This would require a primary surplus of 1 per cent of GDP to stabilise the debt ratio (check it for yourself).

Now what if the financial markets want a risk premium on domestic bonds? Also assume the central bank is worried about inflation and pushes nominal interest rates up so that the real rate (r) rises to 6 per cent. Also assume that the primary surplus and the rising interest rates drive g to 0 per cent (GDP growth falls to zero).

So now the the fiscal austerity (primary surplus) has to rise to 6 per cent of GDP to stabilise debt. The sharp fiscal contraction would lead to recession and as the popularity of the government wanes the uncertainty drives further interest rate rises (via the “markets”). It becomes even harder to stabilise debt as r rises and g falls.

But consider this example which is captured in Year 1 in the Table below. Assume, as before that B/Y(-1) = 1 (that is, the public debt ratio at the start of the period is 100 per cent). The (-1) just signals the value inherited in the current period.

It is a highly stylised example truncated into a two-period adjustment to demonstrate the point. But if the budget deficit is a large percentage of GDP then it might take some years to start reducing the public debt ratio as GDP growth ensures.

Assume that the real rate of interest is 0 (so the nominal interest rate equals the inflation rate) – not to dissimilar to the situation at present in many countries.

Assume that the rate of real GDP growth is minus 2 per cent (that is, the nation is in recession) and the automatic stabilisers push the primary budget balance into deficit equal to 1 per cent of GDP. As a consequence, the public debt ratio will rise by 3 per cent.

The government reacts to the recession in the correct manner and increases its discretionary net spending to take the deficit in Year 2 to 2 per cent of GDP (noting a positive number in this instance is a deficit).

The central bank maintains its zero interest rate policy and the inflation rate also remains at zero.

The increasing deficit stimulates economic growth in Year 2 such that real GDP grows by 3 per cent. In this case the public debt ratio falls by 1 per cent.

So even with an increasing (or unchanged) deficit, real GDP growth can reduce the public debt ratio, which is what has happened many times in past history following economic slowdowns.

Economists like Krugman and Mankiw argue that the government could (should) reduce the ratio by inflating it away. Noting that nominal GDP is the product of the price level (P) and real output (Y), the inflating story just increases the nominal value of output and so the denominator of the public debt ratio grows faster than the numerator.

But stimulating real growth (that is, in Y) is the other more constructive way of achieving the same relative adjustment in the denominator of the public debt ratio and its numerator.

But the best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.

The discussion also demonstrates why tightening monetary policy makes it harder for the government to reduce the public debt ratio – which, of-course, is one of the more subtle mainstream ways to force the government to run surpluses.

Question 2:

Russia was forced to default on its outstanding public debt because it faced a major collapse of oil prices in world markets which meant it could no longer raise the foreign currency necessary to repay the loans via net exports. But the defaults were ultimately due to the currency peg against the US dollar that they voluntarily put in place.

The answer is False.

The question was a relatively straight-forward test of whether you understood what actually happened in Russia in 1997-98, given that more and more mainstream economists are (erroneously) using it as an example of sovereign default that is applicable to other nations at present – especially those that are sovereign in their own currency.

The question had correct details embedded with on major falsehood. The following points were correct.

First, in late 1997 Russia did face a major collapse of oil and non-ferrous metal prices, upon which they heavily depended on to earn them foreign exchange.

Second, they did strongly rely on the export earnings from this sector to get foreign currency to repay the foreign currency-denominated loans that they had taken out in during the liberalism frenzy that followed the breakdown of the Soviet system. There was considerable optimism in Russia at the time and all sorts of opportunists were set loose and their foreign currency exposure rose dramatically.

Third, the defaults, in part were driven by the fact that they had chosen to peg the rouble within tight range to US dollar (a fairly hard peg) and thereby surrendered their currency sovereignty. Once the government pegged the currency and allowed wide-scale financialisation of its economy to occur with foreign-currency loans and foreign banks dominating, they were at risk of insolvency on any foreign currency debts they took out.

Under these circumstances, the economy – both government and non-government sectors – were are risk of any major decline in their export earnings and/or some other exogenous international event that would provoke speculative attacks on the rouble.

The latter came in November 1997 with the Asian crisis which led to speculative attacks on the Russian currency. The speculators knew that the Russian government would try to maintain the peg and was heavily indebted in foreign currencies. So by selling the Russian currency short the speculators knew they could profit.

The problem was that the Russian government played right into their hands and instructed the central bank (CBR) to defend the rouble (that is, maintain the peg) and they lost around $US6 billion in reserves in doing so.

Then in late 1997 oil and non-ferrous metal prices collapsed which reduced their capacity to replenish the lost foreign currency reserves.

The demise was fast and by April 1998 more attacks on its currency led to further foreign exchange reserves being lost in the futile attempt by the CBR to defend the hard peg. Further, oil prices kept dropping.

During this time, the CBR was hiking interest rates in a vein attempt to attract enough foreign investment to help defend the currency. The major impact of this policy was to scorch the domestic economy. The CBR however did not stop bleeding US dollars in its currency defence.

By August 1998 with the collapse of prices on Russian share and bond markets as investors sold off in the face of major fears of devaluation, the Russian government devalued the rouble, defaulted on domestic debt, and pronounced a moratorium on payments to foreign creditors (effectively a default). On September 2, 1998, the government floated the rouble.

So the crisis was the direct result of the currency peg and the massive exposure to foreign-denominated debt.

So why is the answer false?

Quite simply because the government not only suspended payments on all foreign-currency loans but also defaulted on its public debt denominated in rubles.

Even with the peg and the loss of foreign currency reserves, the government could have still always made the payments owing and the repurchases due on its domestic debt.

The fact they defaulted on their own debt was an act of sheer stupidity and the poor advice they were getting. There was never a solvency risk in their own currency. The IMF among others (including a bevy of mainstream economists) were telling the Russian government that they had to implement an austerity plan and convincing them that they needed to “raise money” to fund the deficit – both erroneous propositions.

They could have simply floated and become sovereign and then there was no solvency risk in all debts denominated in that currency.

Question 3:

Imagine that macroeconomic policy is geared towards keeping real GDP growth on trend. Assume this rate of growth is 3 per cent per annum. If labour productivity is growing at 2 per cent per annum and the labour force is growing at 1.5 per cent per annum and the average working week is constant in hours, then this policy regime will result in:

The answer is a rising unemployment rate.

The facts were:

- Real GDP growth to be maintained at its trend growth rate of 3 per cent annum.

- Labour productivity growth (that is, growth in real output per person employed) growing at 2 per cent per annum. So as this grows less employment in required per unit of output.

- The labour force is growing by 1.5 per cent per annum. Growth in the labour force adds to the employment that has to be generated for unemployment to stay constant (or fall).

- The average working week is constant in hours. So firms are not making hours adjustments up or down with their existing workforce. Hours adjustments alter the relationship between real GDP growth and persons employed.

Of-course, the trend rate of real GDP growth doesn’t relate to the labour market in any direct way. The late Arthur Okun is famous (among other things) for estimating the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate – the so-called Okun’s Law.

The algebra underlying this law can be manipulated to estimate the evolution of the unemployment rate based on real output forecasts.

From Okun, we can relate the major output and labour-force aggregates to form expectations about changes in the aggregate unemployment rate based on output growth rates. A series of accounting identities underpins Okun’s Law and helps us, in part, to understand why unemployment rates have risen.

Take the following output accounting statement:

(1) Y = LP*(1-UR)LH

where Y is real GDP, LP is labour productivity in persons (that is, real output per unit of labour), H is the average number of hours worked per period, UR is the aggregate unemployment rate, and L is the labour-force. So (1-UR) is the employment rate, by definition.

Equation (1) just tells us the obvious – that total output produced in a period is equal to total labour input [(1-UR)LH] times the amount of output each unit of labour input produces (LP).

Using some simple calculus you can convert Equation (1) into an approximate dynamic equation expressing percentage growth rates, which in turn, provides a simple benchmark to estimate, for given labour-force and labour productivity growth rates, the increase in output required to achieve a desired unemployment rate.

Accordingly, with small letters indicating percentage growth rates and assuming that the average number of hours worked per period is more or less constant, we get:

(2) y = lp + (1 – ur) + lf

Re-arranging Equation (2) to express it in a way that allows us to achieve our aim (re-arranging just means taking and adding things to both sides of the equation):

(3) ur = 1 + lp + lf – y

Equation (3) provides the approximate rule of thumb – if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour-force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

It is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour-force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it provides reasonable estimates of what happens when real output changes.

The sum of labour force and productivity growth rates is referred to as the required real GDP growth rate – required to keep the unemployment rate constant.

Remember that labour productivity growth (real GDP per person employed) reduces the need for labour for a given real GDP growth rate while labour force growth adds workers that have to be accommodated for by the real GDP growth (for a given productivity growth rate).

So in the example, the required real GDP growth rate is 3.5 per cent per annum and if policy only aspires to keep real GDP growth at its trend growth rate of 3 per cent annum, then the output gap that emerges is 0.5 per cent per annum.

The unemployment rate will rise by this much (give or take) and reflects the fact that real output growth is not strong enough to both absorb the new entrants into the labour market and offset the employment losses arising from labour productivity growth.

Please read my blog – What do the IMF growth projections mean? – for more discussion on this point.

The question has practical relevance in Australia at present with the recent statement by the RBA that its was hiking rates further because real GDP growth was nearly back on trend. The fact is that the trend growth rate is below the required growth rate and so the monetary policy stance is really locking in higher than necessary unemployment.

Question 4:

Students are taught that the macroeconomic income determination system can be thought of as a bath tub with the current GDP being the water level. The drain plug can be thought of as saving, imports and taxation payments (the so-called leakages from the expenditure system) while the taps can be thought of as investment, government spending and exports (the so-called exogenous injections into the spending system). This analogy is valid because GDP will be unchanged as long as the flows into the bath are equal to the flows out of it which is tantamount to saying the the spending gap left by the leakages is always filled by the injections.

The answer is False.

This is actually an example that has been used in the past by macroeconomics teachers to try to teach students the so-called circular expenditure models with leakages and injections.

The basic flaw is that it confuses stocks and flows. I am sorry that I keep batting on about that but it is crucial to a wider understanding of macroeconomics that the distinction between the two concepts is clear in your mind.

The taps and the drains are conceptually accurate because they relate to flows – all expenditure components, saving and taxation payments are flows which are measures as so many $s per period.

A stock has no such time dimension and the only way we can measure it is to take a snapshot at some point in time.

The flaw then relates to the construction of GDP as the level of water in the bath. This is a stock rather than a flow. In the same way as a reservoir is a storage of water which might be 70 or 80 percent full.

But GDP is just the summation of the expenditure flows and is thus a flow itself.

When then national statistician releases the National Accounts and says that GDP was $x billion in the December quarter, they are referring to the sum total of the flow of component expenditure over the 3 month period (October, November, December). They are not referring to a stock of output (which would be inventories or something like that).

The aspect of the question that is true, however, relates to the statement that GDP will be unchanged as long as the flows into the bath are equal to the flows out of it which is tantamount to saying the the spending gap left by the leakages is always filled by the injections.

However the nuance is that it will be the flow of GDP that will be unchanged. The water level is a poor construction of this flow concept.

Question 5:

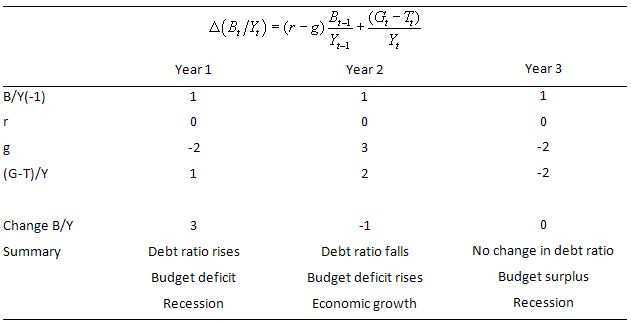

Assume the current public debt to GDP ratio is 100 per cent and that the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate remain constant and zero. Under these circumstances it is impossible to reduce a public debt to GDP ratio, using an austerity package if the rise in the primary surplus to GDP ratio is always exactly offset by negative GDP growth rate of the same percentage value.

The answer is True.

This question plays on the first but investigates a difference aspect of the framework outlined above.

The following Table adds another year to the analysis presented above. You can see that there is a recession being encountered with negative GDP growth of 2 per cent (this is also a decline in real GDP because the inflation rate is zero).

Now the government responds to the deficit terrorists and tries to reduce the public debt ratio by running a primary budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP – it is a negative sign in the table because the construction is (G – T)/GDP which means a surplus is a negative number.

From the formula, the change in the public debt ratio is zero.

As long as the primary surplus as a per cent of GDP is exactly equal to the negative GDP growth rate, there can be no reduction in the public debt ratio.

Of-course, this strategy, which is being pushed onto governments by the conservatives now will likely have to consequences.

First, it will probably push the GDP growth rate further into negative territory which, other things equal, pushes the public debt ratio up.

Second, as GDP growth declines further, the automatic stabilisers will push the balance result towards (and into after a time) deficit, which, given the borrowing rules that governments volunatarily enforce on themselves, also pushed the public debt ratio up.

So austerity packages, quite apart from their highly destructive impacts on real standards of living and social standards, typically fail to reduce public debt ratios and usually increase them.

So even if you were a conservative and erroneously believed that high public debt ratios were the devil’s work, it would be foolish (counter-productive) to impose fiscal austerity on a nation as a way of addressing your paranoia. Better to grit your teeth and advocate higher deficits and higher real GDP growth.

That strategy would also be the only one advocated by MMT.

That is enough for today!

I would like to note, that the EMU restrictions 3% budget deficit and 60% debt/GDP are not arbitrary. Instead these numbers are the logical conclusion on the underlying assumptions, which are indeed out of thin air. The assumptions are: nominal interest rate 5%, inflation rate 2% and GDP growth 3%. Then the ECB deploys your formula: delta(B/Y) = 0,03 = ((0,05-0,02) – 0,03) * 0,6 + 0,03 and the 3% change in B/Y is used to service the interest payment on debt 0,05 * 0,6 = 0,03. Guess this sort of ultra-complex calculations are the reason why we need to accommodate the ECB in a skyscraper in Frankfurt.

Happy birthday!

Dear Stephan,

who are the MMTers in D? Are there any? Not sure if /L is from D.

I have searched around on the web and so far found none. I\’d be interested in looking at any blogs of MMTers – I speak and write German.

Gruesse

graham

Thanks Stephan

My reference to being arbitrary related to the assumptions they plugged in to get these lovely round numbers – as you note. But I always thought the ECB deserved more space than they have in Frankfurt – there are a lot of “big heads” to house there.

Anyway, your vigilance is appreciated.

best wishes

bill

Graham,

As far as I’m aware of there are none. At least not living ones 😉 Georg Friedrich Knapp is dead.

DE Monetary Thinking = BuBa Thinking. That happened long ago and is now a sort of secular religion. The high priests are Alex Weber, Jürgen Stark, Otmar Issing et al. The Buba Gang. They together with neo-liberal economists have monopolized the public discourse. The only dissent comes from the socialist left, but basically also the left subscribes to orthodox monetary policy and argues mainly about welfare redistribution. But beside all the propaganda I think there are two historical reasons why MMT might have a hard time in Germany.

First Germany and also my home-country Austria obsess about inflation. Although there are almost no living memories about Weimar left, the hyperinflation fear and the money printing press myth are alive and very well. So for the average German reading about Blanchard’s proposal of an inflation rate of 4% was like reading about an upcoming catastrophy. He could as well have said: let’s have double-digit inflation per month. This irrational fear is also the reason why a lot of otherwise rational people subscribe to views from lunatics like Peter Schiff and Marc Faber. You can have the most rational theory on earth, it won’t cure irrational fear ingrained over generations of folks.

Second one of the implications of MMT, that government acts as an employer of last resort is historically problematic. People associate with such an proposal the substitution of unconditional welfare benefits with public works enforced by the government. Which is for the obvious historical reasons anathema especially for the left. You just have to look at the response of the left to the latest neo-liberal assault on welfare for the long-time unemployed. Public works provided by the government was not on the agenda. The discussion is whether an unconditional basic income for every citizen might be the answer to the malaise of long-term unemployment.

From a personal perspective I can only tell you, that being a proponent of MMT and having a discussion on economic affairs with Germans I’m considered to be a lunatic and completely out-of-sync with the real world. Not exactly a position aspired to by academic voices.

Cheers,

Stephan

PS: There aren’t a lot of German economic blogs. The few existent are either by neo-liberal think-tanks and libertarians (despite their crazy ideas I must say their marketing drive is admirable) and strong left leaning individuals. Germans have a different approach to blogging. The general idea is, that if you don’t have an underwritten authority on the subject, it’s better to say nothing. Only Prof. and Dr. will establish your credentials 😉

“…designed to lull you into incorrect analytical thinking.” I knew it, you sneaky b***d.

In other news, Krugman notes (subtly) that the hysteria over debt is overblown – and that it is more important to have real GDP growth than to just “inflate” debt away. I have this feeling that he understands MMT, but knows enough politically not to say so. Also FWIW, he has referenced Marshall Auerback in one of his recent blog posts, but confuses Marshall’s implication re: Latvia and Iceland with Spain and Greece,

pebird: Also FWIW, [Krugman] has referenced Marshall Auerback in one of his recent blog posts…

Interesting. I follow him but must have missed that blog. I”d say it qualifies are a last mile update though. First, the established figures have to give these idea and people putting them forward cred and then later slowly come out yourself. I don’t think anybody with a vested interest is suddenly goving to announce that they now get it and have realized they were wrong. I expect that the some of the names will work this out together in tandem. Galbraith took a big step this last week, for example. And that now makes both Marshall and Warren cited by big names.

Progress.

As an aside, suppose that we do buy the household-government budget analogy, then why worry about the debt/GDP ratio as opposed to the interest_payments/GDP ratio?

A bit more than curious. 😉

Thanks.

Krugman’s prescriptions for current policy have been good, though he gets there by classical Keynesianism rather than MMT. Fiscal intervention is called for because monetary policy is up against the zero bound. Longer term, he’s worried about “confidence” in the bond markets leading to a “death spiral”. There’s no risk of outright default, so the only “confidence” issue is a fear that the purchasing power of dollars will decline by the time a bond comes due (inflation is feared). He also made a bizarre statement that Govts should prefer not to borrow primarily with short-term paper because of the risk of a liquidity crisis. Huh?

Min: I’ve been trying to sort this out in my mind. Dick Cheney famously said, “Deficits don’t matter.” I’m trying out the idea that he was close, but subtly wrong. Deficits, as a flow variable, do matter (Bill here argues daily that they can be used for good when private demand slacks; clearly inappropriately large deficits during high utilization of the factors of supply could lead to inflation). But perhaps the debt, as a stock variable, doesn’t. The only possible problem I have in mind is inflationary pressure if debt servicing becomes large enough to drive the deficit. That could happen if the debt is large after several years of heavy deficit spending to get us out of this recession, then as we reach full employment inflation starts to threaten, and the central bank wants to set rates high to control it. At that point, “debt service” becomes a large flow variable of money injected into the economy. The central bank could decide to bring rates down, all the way to zero if it wanted, but that seems like a questionable idea when we’ve just said inflation was threatening.

I suspect that some of the MMTers here will say that under those circumstances, taxes should be raised to counter the debt service flow — fiscal policy to set an appropriate deficit level. That should bring down inflationary pressures, allowing monetary policy to set lower rates, in turn reducing debt service, and the “death spiral” is broken. Or, they might argue that the problem will never in fact arise or will be self-mitigating, because inflationary pressures will only occur if the economy is firing on all cylinders which will automatically bring down the deficit. I can see the self-mitigation factor, but I’m not convinced the concern can be entirely dismissed.

One of the things that caught my eye in the IMF staff paper that Bill critiqued a few weeks ago was this (paraphrased): “We treated the economy as having one gauge to monitor (inflation) and one control knob (short term rates)”. MMTers are clearly more inclined to monitor the unemployment gauge and use the fiscal policy knob. But I don’t think that this escapes the basic balancing act between inflation and unemployment.

I’m still rather a newbie here. I sense that MMT is correct, and its insights can help us avoid some major policy errors that come from muddled thinking. I’m still assessing whether I find it complete. I don’t yet have a good handle on the MMT approach to inflation and inflation expectations, asset prices and bubbles, and a few other things….

“Tom Hickey says:

Monday, March 8, 2010 at 7:22

pebird: Also FWIW, [Krugman] has referenced Marshall Auerback in one of his recent blog posts…

Interesting. I follow him but must have missed that blog. I”d say it qualifies are a last mile update though. First, the established figures have to give these idea and people putting them forward cred and then later slowly come out yourself. I don’t think anybody with a vested interest is suddenly goving to announce that they now get it and have realized they were wrong. I expect that the some of the names will work this out together in tandem. Galbraith took a big step this last week, for example. And that now makes both Marshall and Warren cited by big names.

Progress.” which is ironic because krugman constantly talks about and rails against how being right makes you a “not serious” person in washington.

Stephan, I think you are too pessimistic here. I live in Austria (but not Austrian :)) and inflation fears are definitely high here. However this debate reminds me very much of the discussion about Germany vs Greece in another thread here. WWII was a very tough exercise and execution of my nation but I have no hard feelings about Germans or anybody in this regard. It is a long history whether you like it or not. I personally prefer to move along and look into the future. Coming back to MMT and hard-core Europe, it is a very slow process and will require generations (lets hop not!) but things are brewing. I slowly started to spread ideas in my neighborhood of bankers and even bankers seem to be gradually accepting the fact that the gold standard was over 40 years ago. Resistance is high but at the end of the day, and it was also mentioned on still another thread here, it will be the question of a single country (far away from hard-core Europe) switching its policy to MMT logic and then the whole building of neo-liberalism will fall apart overnight. We simply need to get ready before that happens.

Sergei,

I can only hope you’re right with your assessment! Regarding the boiling debate about WW2 and outstanding reparations: I think this issue is off topic and not very helpful. It must also be settled, but I can’t see any connection to the current Greek malaise. Like said in the other thread the Greek government had the chance and they blew it by giving in to EU pressure. Cowards! My point of view was only confirmed today: The German Finance Minister Schaeuble is working on a plan for an EMF with the explicit rule, that EMU members will be prohibited to turn to the IMF once EMF is in place. So imagine what would have happened if Greece simply turned to the IMF just to drive home the point?

Now maybe MMT might take off given your scenario. My impression is, that most people simply confuse the differences between a government budget and a private household budget. Which is understandable. It might be annoying, but I think the crucial point is to iterate the difference between the two to people ad nauseam. And again I hope you’re right with your optimistic analysis!

Funny stock flow & accounting messups in the video here :

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2010/03/06/talking-about-the-blog-ii/ @ 41:00

Hopes raised at 39:20 lasted 40s only.

Dear Ramanan

I don’t know why you bother with it … there is a fundamental disconnect in the accounting with that approach and no willingness to learn.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

Hadn’t bothered to look up. JKH pointed it out at WM’s blog. I guess someone would have sent JKH the link as well as he wouldn’t bother too.

The comment was just for people in love with non-linear dynamics and business cycle theories and to let them know how easy it is to go wrong in the first step itself.

Ramanan,

I started listening to the SK video because I was interested in his thoughts about blogging per se, rather than a rehash of his methodology, which I’m quite familiar with. I’m not sure his approach is as much stock/flow inconsistent as it is just plain unnecessary. He’s created his own elaborate set of accounts when there’s no need to. I’m believe him when he says its “consistent”; I just don’t know what he ends up with. The last time I commented there, he seemed genuinely appreciative of the financial accounting “lesson”, as he intimated in the video, and he also admitted to having no formal accounting training. It’s a shame and too common a problem. And because he doesn’t know financial accounting, he doesn’t realize that proper financial accounting essentially has differential equation logic embedded in it (i.e. the relationship between stocks and flows).

JKH, Bill, Ramanan,

Now I understand where you are coming from.

The early models were built without fiat money. They were only supposed to capture the dynamics of a pure credit system. The only element I strongly disagree with was non-destruction of credit money when the debt is repaid – but this was not a leak, the revolving funds account was just an unnecessary component. If credit money can be created ex nihilo when the model is initialised there is no need to store it on the revolving fund account when debt is repaid. If you remove that column from the model nothing will change.

I believe these models provide a quite obvious description of reality for a hardware engineer who studied circuits theory for 4 semesters (like me) before becoming a programmer (because I couldn’t find a decent job). They are the application of control theory to the field of economics. They are not obvious for an accountant. This is the key point I believe. Please do not assume that the introduction of abstract stocks and flows is inconsistent with the reality. It is a form of abstraction. The purpose of the model is to show that even if we assume that flows (production, investment and spending) are simple functions of stocks – the system behaves like a predator-prey model. This is probably the “business cycle” aspect mentioned. But there is also an inherent limitation in this approach.

The simple models have reached their limits. I believe that more complex models will follow.

I believe the main criticism of the models employed by MMT scholars is that they just correctly define stocks and flows but do not describe the dynamics of the system in terms of how flows depends on themselves and on other parameters.

I think that both approaches are in fact complementary.

Personally I think that posts written by JKH were one of the best on the SK’s blog I have ever seen there.

Yes JKH – very true.

Re: “Personally I think that posts written by JKH were one of the best on the SK’s blog I have ever seen there.”

Would someone kindly furnish the URL for these?

Henry,

This may help (you’ll need to fiddle a bit):

http://www.google.com.au/#hl=en&source=hp&q=JKH+site%3Ahttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.debtdeflation.com%2Fblogs%2F&btnG=Google+Search&meta=&aq=f&aqi=&aql=&oq=JKH+site%3Ahttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.debtdeflation.com%2Fblogs%2F&fp=2e59843abd0061ca

Please have a close look at this thread:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2010/01/13/the-ignoble-prize-for-economics/?cp=all#comments

Stephan,

I’m engaged in a debate at WCI about this topic — government debt is financed at a rate *lower* than the GDP growth rate, because it is funded with medium maturity. For both the U.S. and Canada, the real interest cost was historically about 1.3% less than the real GDP growth rate. You can gather data for the EU nations, but I would be surprised if the numbers were very different.

Even during the Gold Standard era, solvency was never an issue due to cash-flows. The real risks were always lack of investor confidence in the government’s tax-collecting ability, or the ability of the economy to grow — the era of positive GDP growth rates really started in the 19th Century, and prior to this time GDP was not assumed to grow exponentially.

In that case, I have my own back of the envelope calculations, in which the EU should *require* minimum deficits and have a target Debt/GDP in order to limit the leverage of the private sector. But we do not want to encourage asset bubbles, so we want only enough Debt to stabilize reasonable levels of asset prices.

Say we want to cap leverage at L, meaning that we want the private sector to be able to withstand asset price swings of 1/L. Here, L = 3 seems reasonable, but you can pick other numbers as a matter of public debate.

In that case, let L = leverage, G = GDP, g = growth rate of GDP, r = rate paid on government debt, D = government debt.

L = A/D, which we’ll proxy by

L = G/(3gD) (assuming capital’s share of income is 1/3, and P/E multiples are 1/g)

==> D/G = 1/(3gL)

So this gives us a target Debt/GDP of 220%.

Nations which have a lower level are forcing the private sector to incur more leverage, and thus destabilizing their EMU partners. Maybe L = 3 is too low, and we want L = 4 — but this should be a topic of public debate that is a bit more meaningful than arguing about D/G or solvency. Moreover, this gives us a way to distinguish whether the government is to blame for not supplying enough liabilities, of whether the government is to blame for creating too many assets based on fundamentals. I.e. maybe capital’s share of income has grown (increasing leverage), or maybe there is an excess of borrowing, etc. Any additional increases in leverage will be met by government actions that are revenue neutral — e.g. forcing write-downs of debt.

Moreover deficits will oscillate about the business cycle, as a Debt target is more stable.

Continuing to estimate target deficits, let N = deficit. Then dD/dt = N + rD, so d/dt(D/G) = N/G – (g-r)(D/G)

So to stabilize D/G at 220%, with g-r = 1.3%, we would need a deficit to GDP ratio of 3%, but that would be a floor, not a ceiling, provided that D/G was below 220%.

RSJ,

to stabilize debt to GDP at any \”optimal\” level deficits are *required* to be: nominal_GDP_growth * optimal_debt_level. Then asymptotically current debt to GDP ratio will arrive at the optimal level regardless of the current ratio itself. This will obviously also stabilize private debt relative to GDP.

However I have serious doubts that it is possible to arrive at an objective leverage ratio based on economy-wide asset levels. Leverage has always been defined by looking at cash-flow, e.g. ICR (interest coverage) and DSCR (debt service coverage). You are right that value leverage (LTV) gives an idea of the potential to survive the market price shocks but this looks like a wrong place to start as (and I think we all agree) it is the task of the government to minimize such market price shocks via supply/demand regulation. The dominant FED mentality is to clean the mess after the bubble burst and they use interest rates to ease cash-flow shocks. While value leverage is an idea of credit risk in adverse scenario it is possible to have going concerns with negative equity if cash flows allow this and give time to fix the equity part of leverage.