In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader – Part 2

This is a second part of an as yet unknown total, where I investigate possible new policy agendas, which are designed to meet the challenges that Japan is facing in the immediate period and the years to come. This is also in the context of the elevation of Ms Takaichi to the LDP presidency and soon Prime Minister. She has suggested that her policy agenda will shift somewhat from the current government position, in the sense that she wants lower interest rates, while the majority of economists want higher, and she is advocating further fiscal expansion, while the mainstream want austerity. In the first part I examined the inflation issue in Japan, which suggests that the mainstream view that rates have to rise is misguided. Today, I am considering the scope for fiscal expansion.

The series so far;

1. Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader (October 6, 2025).

2. Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader – Part 2 (October 9, 2025).

Ms Takaichi is an advocate of Abenomics, which was defined by a commitment to robust fiscal activism and low interest rates, with the Bank of Japan keeping government bond yields close to zero via its massive bond-buying program.

Last year, the new leader told the Bank of Japan that it was “stupid to raise interest rates now” and she has consistently articulated a view that interest rates should not be used as a counter-stabilising policy tool (Source).

One of her current advisors is a colleague of mine at the University and we have published several articles and books together.

As a result, the policy advice is fairly consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), although she is also getting input from mainstream economists.

But the combination of stable low interest rates (that is, de prioritising monetary policy as a tool to control the economic cycle) and a commitment to use bold fiscal policy interventions to achieve full employment and material prosperity is clearly more MMT than an expression mainstream New Keynesian orthodoxy.

The other interesting aspect of her approach is captured by her statement at the press conference upon taking on the LDP leadership:

The government should take responsibility for monetary policy … (the government) … should communicate closely with the BOJ.

Over the last week, there has not been a lot of commentary focused on this aspect of her approach, but as I signalled in Monday’s post, this challenges one of the shibboleths of mainstream New Keynesian thinking, which has led us all to believe that ‘central bank independence’ is non-negotiable and requires no political influence on monetary policy.

I have considered this issue before in these posts among others:

1. The central bank independence myth continues (March 2, 2020).

2. Censorship, the central bank independence ruse and Groupthink (February 19, 2018).

3. The sham of central bank independence (December 23, 2014).

4. Central bank independence – another faux agenda (May 26, 2010).

5. Senior mainstream economist now admits central banks are not as independent as many believe (June 3, 2024).

The point is that the independence narrative was part of the depoliticisation agenda accompanying the neoliberal takeover of government.

It allowed elected governments to shift the blame for interest rate increases (and the political fall-out) away from itself by claiming that the monetary policy authority was ‘independent’ from government and so on.

Of course, there is no independence.

The elected government typically appoints the senior officials of the central bank so the appointments are political and the history of the RBA board confirms that clearly.

More importantly, the central bank and the treasury departments for each nation must communicate on a daily basis because fiscal decisions have implications for the liquidity in the system, which, in turn influences the state of the reserves that banks hold in their accounts at the central bank, which, in turn, determines what the central bank does in order to manage that liquidity to ensure it is consistent with their current monetary policy stance.

If that all sounds like gobbledygook then I urge you to go back and read some of the posts I have linked to above to get the more detailed explanation which will clear it all up for you.

The bottom line is that at the operational level there can be no independence between the central bank and the treasury – both macroeconomic policy arms are part of the consolidated government sector and must work together for policy consistency to occur.

The interesting point though is that Ms Takaichi is coming out openly about this and making it clear that monetary policy should be the responsibility of the elected government and not handed over to unelected and largely unaccountable technocrats.

That is a marked departure from the orthodoxy.

Where I depart with Ms Takaichi’s stated goals are that she seeks to:

… prioritize economic growth.

I have written before about how Japan should lead the world in showing us how to achieve a sustainable degrowth trajectory while still ensuring the material needs of its citizens are met.

For example:

1. Degrowth and Japan – a shift in government strategy towards business failure? (July 17, 2024).

2. Japanese government investing heavily in technologies to help its population age (October 21, 2024).

With an ageing population, a resistance to large-scale immigration, there are now significant constraints appearing in the labour market in terms of available skills etc.

As I have noted before, over 70 per cent of SMEs, which dominate the economy, are owned by those who on average are over 70 years age.

And there is a resistance to selling those businesses on the open market when the owner gets too old to run them – in favour of passing them down within the family.

However, increasingly the children do not want to carry on the family business tradition and so the businesses close when the ageing owner is done.

So rather than fight against the demographic reality, which is on-going and difficult to reverse within the dominant culture, it would be more sensible to develop a degrowth strategy.

Even if we did not hold that degrowth predilection, it remains to ask just how much capacity there is within the current productive resource availability to accommodate significant economic growth anyway.

I ask that question because to advocate increasing the fiscal deficit implies that the government thinks there is real resource space available to absorb the increased nominal spending without provoking demand-pull inflationary pressures.

So I am doing some research on that question and this is the first take on the available evidence.

I will write more about this topic as my research expands.

The Bank of Japan publishes a quarterly time series – Output Gap and Potential Growth Rate – and the latest data came out on October 3, 2025.

This data provides some evidence we can draw upon to help us determine the ‘growth space’ available to the Japanese government.

The technical paper underlying this data is – Methodology for Estimating Output Gap and Potential Growth Rate: An Update (published May 31, 2017).

I won’t go into the technical details but I have written about the deficiencies of conventional output gap methodology.

For example:

1. The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise (February 27, 2019).

2. The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

3. The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 16, 2009).

4. NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy (November 19, 2010).

5. Structural deficits – the great con job! (May 15, 2009).

6. Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers (November 29, 2009).

My own PhD work was, in part, about this exact issue and my work as a 4th year student at the University of Melbourne (1978) was, in part, about these issues.

The idea of an output gap is conceptually sound – it is pretty clear that we can conceptualise some potential output level beyond which the productive system cannot squeeze any more real output without extra resource capacity being added (capital, labour, land, etc).

The measure of current production is clear enough although measures of GDP are deficient for what they include (for example, pollution) and exclude (for example, home production).

It is also fairly easy to understand the concept of a macroeconomic equilibrium unemployment level where the conflicting distributional nominal income claims between workers, capital and government are consistent, albeit for a transitory period, with the real output available for distribution.

My PhD (and early publications) were, in part, about theorising and operationalising this idea with a path-dependent system.

However, as they say, the devil is in the detail.

We know that ideology distorts the measurement process and the empirical expression of theoretical concepts.

Let me explain.

The Bank of Japan writes that:

The output gap is the economic measure of the difference between total demand as an actual output of an economy and average supply capacity, smoothed out for the business cycle — namely potential GDP – … in the goods and services market of the nation. The potential growth rate is the annual rate of change in potential GDP. In factor markets, the output gap expresses the differential between the labor and capital utilization rates and their average past levels. The potential growth rate is the sum of the average growth of labor input and capital input, and the efficiency with which these factors are used, namely total factor productivity (TFP).

Taken at face value, this is uncontroversial, although the absence of any biophysical aspect on the conceptualisation of potential GDP growth rates is a serious and known deficiency.

But, essentially, the output gap concept is easy to understand.

The problem is that ‘potential GDP’ is not easily measurable and requires us to take a stand on what constitutes full capacity utilisation of labour and capital.

This is where ideology enters the picture.

What constitutes full employment of labour?

In the context of the maximum output that might be squeezed out it must mean having everyone working up to their desired hours.

However, that is not the way the mainstream define full employment.

They consider the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) which is conceptually the unemployment rate where inflation is stable.

It is unobservable and the estimates using statistical means are highly dependent on the assumptions and approach taken.

As I have noted many times before, the statistical accuracy for the known NAIRU estimates is notoriously poor, with wide standard errors – such that they are basically useless for pinpointing some specific full employment level.

Moreover, they are typically biased upwards, meaning that the mainstream depiction of full employment associates much higher unemployment rates with that state than the approach that I take.

The Bank of Japan’s approach is relatively orthodox, initially based on estimating what they call the Labour Input Gap and the Capital Input Gap.

They then come up with a weighted measure of these gaps to define a total output gap.

Then using actual GDP figures derived from the National Accounts, they can subsequently estimate the potential GDP.

Why?

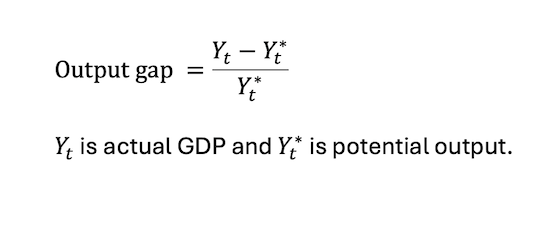

The output gap is defined in simple algebra as:

You don’t need to be a mathematician to be able to work with this definition.

If actual GDP is 100 and potential GDP is 120, then the formula gives:

Output gap = (100 – 120)/120 = -0.166666667 or in percentage terms -16.7 per cent.

That would be a very large output gap.

The Bank of Japan defines the Labour Input as:

The Bank’s potential Labour Input measure uses the same expression “which smooths out the

business cycle”.

What does that mean?

I won’t go into the technical stuff but basically they use statistical tools to calculate a trend and assume this is the full capacity measure.

The difference between this ‘trend’ input measure and the actual measure is the Labour Input gap.

It is problematic because the trend may not correspond with an employment level that satisfies the desire for working hours of the available labour force.

They similarly calculate a Capital Input gap based on the difference between actual capacity utilisation rates and average utilisation rates.

There are all sorts of measurement problems faced in doing that.

But for now, we just assume these estimates have some degree of applicability to the real world.

The fact that the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance use these estimates of the output gap in designing economic policy is a good reason for considering them, notwithstanding my concerns.

They are likely to underestimate the Labour Input gap, which means we can consider them for argument sake, to define the smallest gap – with the reality lying above their estimates.

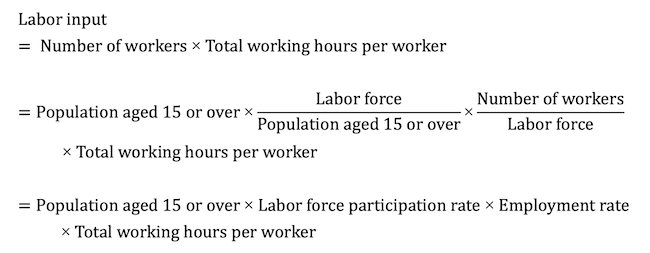

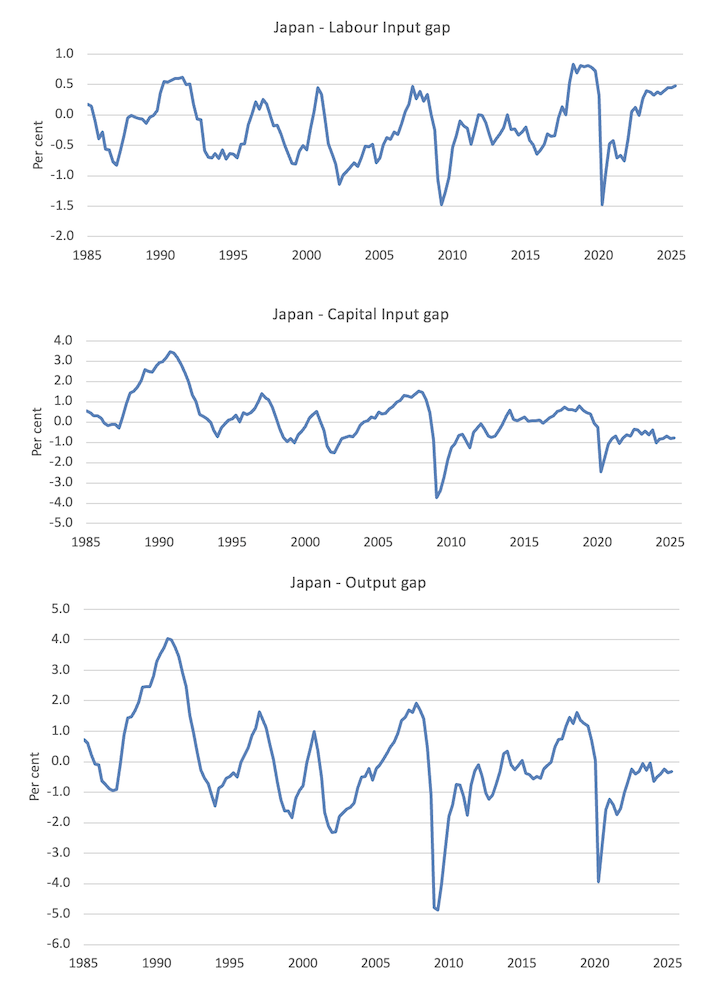

The latest data came out last week (October 3, 2025).

Here is a graph showing the Labour Input gap, the Capital Input gap, and the total output gap between the March-quarter 1985 and the June-quarter 2025.

As at the June-quarter 2025, the Bank estimates an output gap of -0.32 per cent – relatively small.

They estimate the Labour Input gap to be +0.47 per cent, which means the available labour force is working over their trend potential.

They estimate the Capital Input gap to be -0.79 per cent, which means current capital utilisation is below its longer term average utilisation.

So their estimate of a small output gap is based on the idea that the economy could extract more output out of capital stock by working it harder.

So according to these estimates, there is some scope for increasing actual GDP growth using increased net government spending, before tax offsets might be considered.

The question though is how to do that with the labour capacity already well above potential?

I am exploring that question next.

And the context is that there is now a growing antagonism across the political divide for the consumption tax.

I am told that Ms Takaichi is sympathetic to the argument that this tax could be reduced.

Conclusion

An on-going research task which will culminate in a major event in the Diet in Tokyo on November 7, 2025.

I will provide more details of that event in due course.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Where I depart with Ms Takaichi’s stated goals are that she seeks to:

… prioritize economic growth.

I have written before about how Japan should lead the world in showing us how to achieve a sustainable degrowth trajectory while still ensuring the material needs of its citizens are met.”

Sadly, the combination of short-termism and reliance on GDP as the main indicator are going to make things worse, not better, given the knee jerk mindset of the political elite.

I wish I knew how Bill’s thinking might be translated into the essential paradigm shift we need.

Today I read with horror that Reeves wants to reform the Licensing Act 2003 to allow and/or encourage longer opening hours in the hospitality sector in England and Wales because this would contribute to Labour’s drive for economic growth. So, basically, more latre night drinking…..

There seems no intention of even asking the obvious question – Is this an appropriate kind of economic growth, given societal alcohol abuse problems; prospects of increased antisocial disorder; under policing of the late night economy; and impact of extended working hours on poorly paid hospitality workers. ?

The UK Labour government must be absolutely desperate to see this, building new airport runways, licensing new fossil fuiel exploration and extraction, a dozen new 400Mw nuclear plants, high energy consuming data centres, and various other unsustainable developments. But hardly anyone seems to demanding answers to the right questions.

About a year ago Myles Allen, climate scientist, insisted that no fossil fuel extraction that involved a net increase in carbon emissions was permissible. I don’t agree that the absolute requirement for pre-market carbon capture and storage – his proposal – is remotely possible, but his crucial point is that future development must not make matters worse on this wee planet.

I think it is incumbent on the pro-growth lobby to identify and codify several crucial metrics if growth is to be pursued, or licensed :-

1) increased non renewable resource extraction and consumption;

2) increased pollution and impacts;

3) other sustainability metrics (such as land use intensity);

4) social and health impacts;

5) workforce demands;

6) linked infrastructure demands;

7) EROEI

I am sure there are others…

The ghost of Arthur Pigou needs to haunt and taunt the entire mainstream economics profession.

TiPi: Technically speaking, there are very few ‘unsustainable’ developments, since very few would require resource inputs that exceed the biocapacity of the local area or nation. Indeed, saying something like, “I’m going to do X and Y so that my house or business is sustainable” is meaningless if there are enough houses and businesses doing the same thing and our collective resource requirements exceed biocapacity. My point is that sustainability is a macro concept and what we do at the micro level only affects the throughput-intensity of each activity, as important as that is. Too many people doing too many things can be unsustainable regardless of how much we all do to lessen the throughput-intensity of each activity.

By and large, we are doing a reasonable job of reducing the throughput-intensity of most activities, but the throughput savings have been more than absorbed by the rise in the number of all activities (by physical growth, in other words) – the Jevons Paradox at work. Humankind has halved the throughput-intensity of Gross World Product over the past 50 years, but population and per capita GWP have doubled. Hence, global throughput (Ecological Footprint) has doubled and is now 1.8 times global Biocapacity. Had we kept global population constant over the last half century and adopted a policy where percentage increases in per capita GWP were only permissible if matched by the same percentage decrease in the throughput-intensity of GWP, global EF would be 0.9 x global Biocapacity – that is, it would be as it was fifty years ago, which was ecologically sustainable (only just!). An example of the same decrease in the throughput-intensity of GWP, but where one scenario is sustainable, and the other is not, all because one involves excessive growth.

Exactly what we should be allocating resources towards would come into sharper focus if we placed a throughput constraint (caps) on the macroeconomy. Allocating some of a sustainable rate of throughput towards energy-hungry data centres would require taking resources away from other things we desire (in some cases, need). Population growth would do the same – resources that could be used to further the welfare of existing numbers of people would have to be reallocated to meet the needs of more people. I’m certain many fewer people would favour population growth in a throughput-constrained world.

But, no, to some extent, we avoid these choices (how we should allocate the resources we extract from the ecosphere) by avoiding the most important sustainability-related decision of all – that is, limiting the total throughput of all resources to a sustainable rate (i.e., one within the ecosphere’s biocapacity). Greater efficiency (reducing the throughput-intensity of individual activities) will not, by itself, lead to ecological sustainability unless we are prepared to cap the rate of throughput to one that is within the ecosphere’s regenerative and waste assimilative capacities. It hasn’t done it to date (global throughput has doubled at the same time global throughput-intensity has halved), and I don’t expect it to do it in the future.

Your idea of metrics for this and that are important but only in terms of how we should best allocate a sustainable rate of throughput (what we should produce and maintain) and how all final goods and services should be distributed (if we think equity matters). Apart from perhaps 1) and 2), they won’t assist one iota in bringing about a sustainable world.

Philip

I wish I could share your optimism on the future sustainability of most economic activity with a capping approach.

Our cooker blew last week and even a global electrical manufacturer had no spare part available for repairs. All that was required was a single simple exchange module, easily fitted. I have managed to undertake a wide range of fettling through the decades, but non availability of even basic parts seems to be increasing, not reducing.

Practically speaking, there is no sustainability whatsoever with this type of consumer durable and much other product manufacturing.

My local IT expert tells me Apple have actually reduced the repairability of their Macbook range in the last 5 years.

The circular economy cannot begin to emerge successfully with such continued built in obsolescence and dire levels of materials recycling. The market will certainly not adjust to any environmental metrics as it stands, at whatever economic aggregate output.

Sadly, I really do not see any way of currently reducing the resource consumption overshoot, let alone energy consumption, and am increasingly persuaded that Myles Allen’s pessimism on net zero timescales failing badly is the most likely outcome, as well as continued resource mismanagement.

TiPi: I’m not at all optimistic about throughput caps being introduced to guarantee sustainability. What needs to be done and what is likely to be done are two different things. The throughput will decline whether we like it or not. If we don’t cap it within the ecosphere’s current regenerative and waste assimilative capacities, both capacities will crash when ecosystems eventually and inevitably collapse. I’m already witnessing a sign of the future with my home state of South Australia experiencing a massive and catastrophic algal bloom along much of its coastline. I’ve seen dead fish wash up onto my local beach for six months. I didn’t realise how much marine diversity there was in the Gulf of St Vincent until it started appearing dead on the beach. The local pod of harmless stingrays has all died. It is having a significant psychological impact on Adelaide residents.

I’m not an expert in algal blooms, but it seems as though a bloom was inevitable. Excessive nutrients being washed down the Murray-Darling Basin, thanks to 2-3 years of very high rainfall in the eastern states (which we can expect more of because of climate change), which ends up flowing into the Southern Ocean not far from two large gulfs (the Gulf of St Vincent and Spencer Gulf), which don’t flush since no major rivers flow into them and any flushing by the Southern Ocean is blocked by a large island (Kangaroo Island), the loss of natural oyster beds (which, in the past, would have gobbled up any algal bloom before it spread too far), and sea temperatures of 2+C above normal (which we can expect more of because of climate change) have provided the perfect ingredients for what is now occurring. I assume these perfect ingredients will emerge together frequently in the future. Yet there was no contingency plan to deal with a bloom or assist people who depend on the health of the two gulfs for their livelihoods. It has been financially devastating for some people. As for the Gulf of St Vincent ever recovering, who knows? It’s almost as good as dead, at present. Dead zones will become common in the near future as ecosystems collapse, and economic systems that depend on the throughput they provide will collapse too.

The ‘circular economy’ is a myth. The term, when uttered, must be music to the pro-growthists ears, not unlike ‘green growth’. They’ll say that if we can perpetually circulate matter and energy within our economic systems (as the circular flow diagram found in mainstream economics textbooks depicts), we can have GDP growth forever. All we have to do is circulate the matter and energy at a faster rate. A circular flow diagram may adequately describe the flow of abstract exchange value (factor payments from firms to households, and spending by households out of their factor payments on goods and services produced and sold by firms), but it fails to describe the flow of matter-energy from which the goods and services, of which GDP is comprised, are made. GDP may be measured in dollars or Euros, or whatever, but a dollar’s worth of petrol is a dollar’s worth of a real thing. And no service can be provided without real things. I’m yet to hear of someone getting a haircut from an imaginary barber using imaginary utensils while sitting in an imaginary barber’s chair in an imaginary barber’s shop. A case of output at the economy’s tertiary trophic level (services) being made possible by the output of the economy’s secondary trophic level (manufacturing), which is made possible by the output of the economy’s primary trophic level (agriculture, forestry, mining, etc.), which is only made possible if there are plenty of healthy natural capital stocks to draw from (the Gulf of St Vincent currently excluded).

The economic process is ultimately a linear one, as is clear once it is recognised that an economic system has a trophic structure, not unlike any other physical system. The economic process involves the linear throughput of matter-energy as natural resources are transformed into wastes by production (rearrangement of matter-energy) and consumption/depreciation (further disarrangement of matter-energy), albeit some of the matter-energy exists in the form of useful goods and services in the meantime (prior to their consumption/depreciation). There are opportunities to reconcentrate some waste materials, but only by using more energy. However, materials recycling is no different to eddies/whirlpools in a river carrying water from a mountain to the sea.

Power is presently in the wrong hands for anything positive to eventuate from a sustainability (and equity) perspective – hence, throughput caps and a Job Guarantee are off the political agenda. Power has been in the wrong hands for 11,000 years following the advent of agriculture. But even if power was in the hands of people with the best intentions, it would be useless unless they have a proper understanding of how economic systems function and their biophysical connection and relationship with the ecosphere that sustains them. I’m afraid that a lot of well-intentioned people don’t understand enough to achieve the outcomes they desire and, when they have some degree of political power, promise. Their failure has led to voter disillusionment with the political Left and the rise of the political Right.

Yes, power has almost always attracted the wrong persons, and I share your view that the current political elite are highly unlikely to prioritise the planet over their own status.

We have even been experiencing algal blooms in the north Atlantic in those years we get a spike in summer water temperatures off the British and Irish coast. A few years ago there was a 5°C summer peak above our normal July water temps. Incredibly disruptive to fish migration, as well as ecosystems.

Tuna even reappeared off Cornwall.

It is definitely an accelerating phenomenon. Lough Neagh is now in total decline as a result of eutrophication from agricultural pollution. Algal blooms are almost ever present.

And Scottish salmon fish farming practices have already been signficantly changed given higher water temps with much higher mortality rates.

Most biophysical processes are not actually linear, but but are cyclic – such as water, carbon, nitrogen etc. It is human misunderstanding and abuse of the carbon cycle that has mostly got us into the present mess.

I don’t read conventional economic theory books, and I don’t know anyone in environmental management who would have faith in such simplistic models. Theoretical economists are not generally regarded as experts in resource management.

I was involved at the practical end of environmental management for many years and closely involved with reclamation of demolished building materials and recycling into new uses.

There is a materials equivalent to the EROEI equation, but it is not necessarily negative as there are offsets which do not apply to EROEI.

The construction sector generally has a horrendous record of waste, and dire rates of recycling and reuse, especially in materials with high embodied energy like window glass.

The circular economy anything but a myth to those practically involved in waste management but I know of no-one who understands resource management who does not get entropy or that reclamation of non renewable resources is always on a % basis.

TBH I’ve not heard anyone practically engaged in repair, reuse and recycling either who claims the practices provide a justification for continued perpetual economic growth, only as a sensible efficiency measure – and that mostly in mitigation of resource overshoot.

Yes, increased recycling itself does generate new economic activity so new repair and waste recycling and/or reprocessing infrastructure does technically raise GDP and hence growth, and that is definitely used as a selling point by circular economy advocates like Ellen MacArthur who are strongly campaigning for behavioural change, given the very low base that exists in our present throwaway society.

Sadly, I think our current rates of recycling are still well below national environmental targets in Scotland.

My original comment intended to support Bill in his own campaign in changing attitudes to degrowth by qualifying what future economic activity might be acceptable, and what criteria are needed to evaluate such potential prospective developments.

I will continue to endorse all repair/reuse/recycle enterprise that does satisfy those criteria, howsoever badged.