It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Japanese government investing heavily in technologies to help its population age

The – Japanese National Institute of Population and Social Security Research – is the go-to place for understanding demographic trends in Japan. The latest revisions to the population estimates (as at 2023) show that the current population of 125.5 million will shrink to 96 odd million by 2060 and then 87 million a decade later. There is a rapid decline after that expected. The male population is shrinking faster than the female population. Much has been made in recent weeks of Japan’s slide down the GDP world ranking. First, China overtook it into 2nd place a few years ago and now Germany is moving into third place. India is projected to push Japan out of fourth place next year. Some have referred to this as “Peak Japan” with the population dynamics likely to push the nation further down the GDP table. There is a lot of anxiety among policy makers here about that ‘fate’. My perspective differs. In fact, I think that the challenge is not to solve the population decline but rather to work out ways to live well with a smaller population, and demonstrate to the world how a planned degrowth strategy can be achieved with minimal disruption to material security.

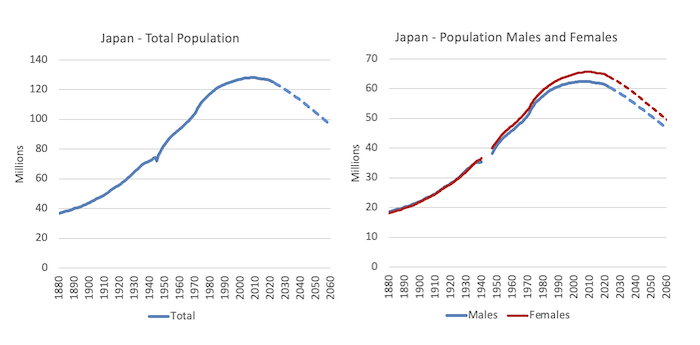

The latest population projections for Japan are depicted in the following graph with the left panel showing total population (in millions) and the right panel the sex breakdown.

As I noted in the introduction, the decline is forecast to accelerate rapidly after 2060 as the age profile shifts further and further into the elderly cohorts.

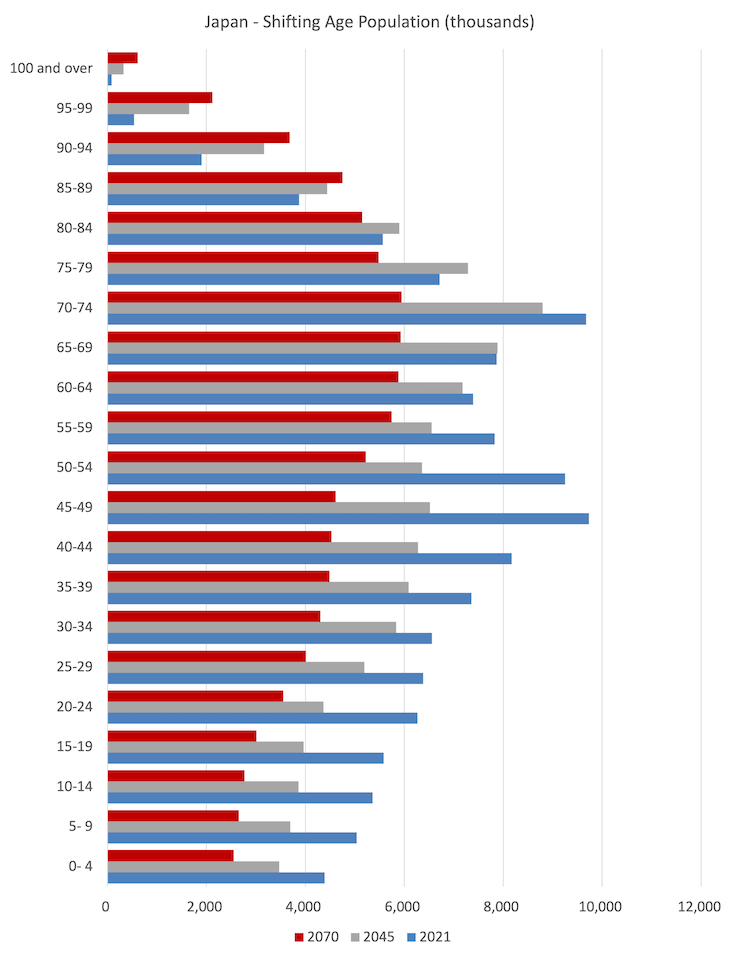

The next graph shows the shift in age groups for 2045 and 2070 relative to 2021.

You need to study the graph carefully to trace the shifting heights (horizontally) of the different age group bars over time.

Japan is just leading the advanced world down the population decline path, a path that must happen globally if we are to deal with the climate change issues.

There are simply too many people on a finite planet and curtailing the population growth has to be a priority.

Clearly, explicit population control approaches are not seen as being viable because they invoke fears of profiling etc.

Which means these natural ageing demographics should be applauded and not used as a motivation to introduce new policies that try to reverse it.

A research report published in The Lancet (May 18, 2024) – Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 – found that:

Fertility is declining globally, with rates in more than half of all countries and territories in 2021 below replacement level. Trends since 2000 show considerable heterogeneity in the steepness of declines, and only a small number of countries experienced even a slight fertility rebound after their lowest observed rate, with none reaching replacement level. Additionally, the distribution of livebirths across the globe is shifting, with a greater proportion occurring in the lowest-income countries. Future fertility rates will continue to decline worldwide and will remain low even under successful implementation of pro-natal policies. These changes will have far-reaching economic and societal consequences due to ageing populations and declining workforces in higher-income countries, combined with an increasing share of livebirths among the already poorest regions of the world.

Therein lies the issue.

The advanced nations are all ageing and will experience Japan-like population declines in the coming decades.

However, the poorest nations are going to add to the population pressure as time passes.

The Lancet research shows that:

1. By 2060, fertility rates in around 75 per cent of nations (155 from 204 nations) will be lower and will not sustain population size.

2. The the low-income nations’ share of the world’s livebirths will rise from 18 per cent in 2021 to 35 per cent in 2100.

3. Sub-Saharan Africa will deliver 50 per cent of the global population expansion by 2100.

These trends are very challenging given that degrowth requires our energy footprint to decline substantially yet the requirements of lifting the poorest nations out of poverty make that challenge nigh on impossible to achieve under current behaviour and system structure.

I will deal with the global distribution of economic and population growth in later posts as our research develops.

However, the anxiety in Japan, which, in part is being fueled the likes of the IMF, who project that the shrinking population will make GDP growth in Japan very difficult – they predict that Japan will lose 0.8 points per year off GDP growth over the next several decades.

That prediction then sets off the mainstream alarm bells – that the government will run out of money because there will not be sufficient tax revenue coming in to cover the rising expenditure needed to sustain the ageing and sickening generations.

They also predict that there will be a dramatic surplus of housing that will undermine the viability of the development and sales industries.

Relatedly, the IMF has argued that an ageing population undermines the profitability of the banking sector (due to lower demand for credit), which will then encourage higher risk speculation to occur and increase the possibility of financial crises.

One problem with all these horror stories is that they assume we should value the sectors at risk.

They never consider that part of the adjustment to the ageing society is that we wipe out the private banking sector which has a poor track record anyway when judged in terms of societal well-being rather than advancing the interests of private profit.

And if there is a surplus of homes, that can provide the scope to create more green space and bring food production back into local areas to reduce the transport distances (and save energy).

Property developers are a blight on the world not a boon.

And, of course, the fears that the fiscal situation will cause the government to run out of money is without any foundation at all given the Japanese government (via the central bank) issues the currency.

The pattern of public expenditure might shift – less schools and more aged care – but the capacity of the government to facilitate that spending doesn’t change.

Further, the likelihood of a declining tax base presents no fundamental problems once we understand that a major function of taxation is to reduce purchasing power so that there is space for the government to spend into without invoking inflationary pressures.

Older people will spend less anyway.

I recently read a new study (published October 3, 2024) – Japan’s Aging Society as a Technological Opportunity – by Stanford University researcher Kenji Kushida.

He rails against the mainstream view that Japan is losing its authority in the world as a result of its shrinking population.

He notes that:

… fewer working-age people must support a ballooning retired population. Healthcare costs are spiraling, and a broad array of social issues are being triggered by large elderly populations and a graying workforce. Depopulation in rural areas is accelerating, leaving high concentrations of aging residents who need more services while the number of providers of such services plummets.

However, far from casting gloom, he argues that these trends:

… offer technological opportunities for the country to become a leader, and for international technology collaborations … [and] … Japan’s demographic realities are accelerating specific technological trajectories that are transforming the fundamental nature of work.

There are two accelerating trends in the Japanese labour market now:

1. Automation – which is helping to solve the problem of not enough workers to do essential tasks.

2. Augmentation – which is “about enhancing the capabilities of people, whether through increasing efficiency or upskilling—allowing workers without specialized skills to perform specialized tasks.”

Both trends offer Japan the incentive to invest heavily and become a leading nation in dealing with declining populations.

The article details explicit characteristics (such as a “rapidly maturing start-up ecosystem”, etc) that will allow Japan to become “a leader in global markets” when it comes to dealing with these demographic challenges.

It also provides ideas as to how “Japan’s technological trajectories” can help deal with the alarming demographic shifts (such as “by 2030, between 20 percent to 22 percent of the population over age sixty-five will suffer from dementia.”)

He cites Japan’s past record in dealing with inherent constraints.

Such as, Toyota’s development of the J-I-T system to solve the “lack of physical space in factories in Japan”.

We read that technology is already helping solve the skills-gap.

The new line of “ICT (Information and Communications Technology) Construction Equipment” that Japanese companies have introduced allow, for example, a highly skilled task such as excavation to be done by a new worker using the semi-automatic equipment.

The technology replaces years of experience which means that new entrants can not only do more immediately but at much higher levels of precision.

Importantly, he notes that:

… the ICT excavator is not aimed at fully automating the operation—it was deployed to close the skill gap between available operators and the skills needed to perform advanced tasks.

Which means that even though AI algorithms are in use, the human input is still necessary.

He lists many other examples such as the “autonomous hauling vehicles for construction sites” developed by a major Japanese construction company.

He also discusses the future of agriculture and argues that while the farming population is ageing and shrinking, food security can be maintained without a major role being played by ‘corporation farming’.

In fact, the small-lot, mountainous nature of much of the farming land militates against the large-scale corporate food lots that are common in other nations.

Advances, for example, in equipment for rice farming have been dramatic.

And as farms are abandoned, merging interests can better use the new equipment (such as tractors etc) on slightly larger lots.

This is not an endorsement of mega farms, which simply would not work in Japan, except perhaps in the north in Hokkaido.

There is also significant investment by Japanese farm equipment manufacturers in “robots to assist in harvesting fruit” and other tasks.

The Japanese government’s – Smart Agriculture Project – recognises that:

Over the next 20 years, the number of core farmers is expected to decrease to about one-quarter of the current number (from 1.16 million to 300,000), and agricultural production based on conventional production methods cannot ensure sustainable development of agriculture or a stable supply of food.

They are investing massive amounts to transform the way food is produced so that a smaller workforce can produce sufficient food for the population.

The aim is to dramatically increase agricultural productivity in a sustainable way using “state-of-the-art smart agricultural technologies”.

There are currently 217 districts in Japan showcasing this approach.

This brochure – Examples of the latest agricultural robots – lists the “robot technologies that were exhibited at the International Robot Exhibition 2023.”

Think about this for a moment.

The Japanese government understands that the ageing society is not to be understood as the government running out of currency to pay pensions and provide first-class health care.

They realise that the ageing issue or challenge is a productivity challenge – to make do with less workers by the future workforce being much more productive than the previous generations.

The other area where the Japanese are investing heavily is in transportation, given that the average age of the truck driving workforce is getting higher each year – “The average ages of bus, taxi, and commercial truck drivers in Japan in 2021 were 53.0, 60.7, and 48.6, respectively.”

It is an unattractive occupation given the long hours and low pay.

The Japanese government is investing in so-called ‘driver augmentation’ technologies, which involve, for example:

… semiautomated truck convoys, in which one truck driven by a person is closely followed by one or more driverless trucks that are digitally tethered to the lead truck.

In 2018, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) published a – White Paper – which defined the way forward for new technologies in transport, including “driverless follower trucks”.

The government is building dedicated lanes on the large Shin-Tomei Expressway for such technologies.

The list goes on – healthcare, education, and more.

Conclusion

The point is that the Japanese government is not burying its head in the sand as these challenges emerge and delaying action by appealing to spurious reasons such as ‘running out of money’.

There is a lot more that it can do and should do.

And I expect it will.

But the dialogue here is light-years away from the moronic narratives that, say British Labour is peddling out now to justify inaction in areas that need a lot of public action.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Some hope for the world. Japan might end up proving that a country can be better off by improving the quality of the stuff its economy is comprised of, and reducing the resource throughput required to sustain it, instead of continuously trying to accumulate more stuff (and increase the size of the economy). While countries like Australia will have great difficulties reducing their Ecological Footprint, Japan will find it relatively easy. Achieving GHG targets as per the Paris Agreement should be a piece of cake for Japan.

According to my Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) work, Japan’s per capita GPI is already higher than the per capita GPI of Australia, which is higher again than the per capita GPI of the USA despite their respective per capita GDP values being in the reverse order (based on International dollars). I can only see the disparities in per capita GPI moving further in Japan’s favour.

If things do pan out this way, Japan will become a model for the future. It may find it will have difficulties keeping a lid on its population as people elsewhere seek emigration to Japan (I’m being a little facetious).

You can see from the UK Consolidated Fund Account for 23/24, that the Treasury Magic Money Tree had to create £167 billion of new Sterling currency units and inject them into the UK non-government sector. This to cover the Budget deficit. You will see also, that the Sterling Magic Money Tree, as usual, doesn’t get repaid.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consolidated-fund-account-2023-to-2024 Document page 7.

Meanwhile, the US Treasury has expanded its Debt to GDP by some 20%; with the result that the US economy is expanding. MMTers know that the US Treasury is never going to run out of US Dollars. It can pay any bill presented to it in its own currency. Unfortunately, the UK Treasury and a string of amateur politicians have no idea of how a sovereign fiat currency is meant to be operated.

Ehrlich’s work from 1968 onwards was correct in essence if not every detail, as was Limits to Growth (1972). Widespread collapse is not a fantasy given the scholarship on the subject. The human enterprise is approaching twice the sustainable size, with little to no world leadership accepting the problem and its causes. Every nation should pursue population stabilisation as a matter of urgency (or reduction). Then move towards food and energy independence – that would give some guide to population size. It is important to note that national and global biocapacity is continually being eroded as overshoot continues. In short, our life support systems are crumbling. Time for citizens to step up to minimise human and animal suffering.

They may not be burying their head in the sand quite as deep as British Labour, but they are still fixated on economistic thinking and attempts to grow the economy at almost any cost.

I appreciate your point of challenging the “assumption that we should value the sectors at risk”, which is a great insight of MMT.. but this could simply create room for the powerful players in Tokyo to further consolidate their control. Without value, it becomes more a question of power and money.

There are signs that farmland mergers and deregulation is already facilitating predatory corporate farmland use, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/18692729.2017.1256977 , and although technology will play an important role in degrowth transformation, this needs to be part of a transformation that fundamentally questions what and how much we produce. Smart Agricultural Projects and Agricultural Robots feels like other “smart” solutions that will benefit capital accumulation but wont be in the interests of the local communities.

There is no “future” for agriculture, at least in the long term. It is fundamentally unsustainable, even without ridiculous ideas like robot farmers. How are we supposed to build and power those magical robots once the petrol runs out? “Sustainable” power doesn’t help when we run out of the stuff needed to extract that power…

«In 2018, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) published a – White Paper – which defined the way forward for new technologies in transport, including “driverless follower trucks”.

The government is building dedicated lanes on the large Shin-Tomei Expressway for such technologies.»

Maybe with some sort of metal guides with predefined crossings with automated signaling and predefined stops.

Half-joking, because I know they like rail, and the last mile is a big problem, but I’d have to read about it to take it seriously.

“One problem with all these horror stories is that they assume we should value the sectors at risk.”

The first rule of economics is that the economy exists to serve people, not the other way around.

In my opinion your point of view is unique among current commentators and displays an acuity which is simply out of the ordinary, and which is inspiring.

However, if I try to explain to a so called ordinary person that a sovereign government will never run out of money because it can create it, I, and assuredly many others, are met by blank stares. Unfortunately, nobody has been able to explain it in a simple enough manner that the idea (no, the fact) will click with everyone. And since this point is the key in any MMT, and further, discussion, and the opposite view is so entrenched, what is really needed is a pathway to a clear explanation. I fear that this, in itself, is a dilemma surmountable only with great difficulty. We need a great “explanator”.