I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Central bank independence – another faux agenda

There are several strands to the mainstream neo-liberal attack on government macroeconomic policy activism. They get recycled regularly. Yesterday, I noted the temporal sequencing in the attacks – need for deregulation; financial crisis; sovereign debt crisis; financial repression and so on. Today, I am looking at another faux agenda – the demand that central banks should be independent of the political process. There has been a huge body of literature emerge to support this agenda over the last 30 odd years. The argument is always clothed in authoritative statements about the optimal mix of price stability and maximum real output growth and supported by heavy (for economists) mathematical models. If you understand this literature you soon realise that it is an ideological front. The models are note useful in describing the real world – they have no credible empirical content and are designed to hide the fact that the proponents do not want governments to do what we elect them to do – that is, advancing general welfare. The agenda is also tied in with the growing demand for fiscal rules which will further undermine public purpose in policy.

The WSJ carried a story today (May 25, 2010) from Eamonn Butler who is attached to the Adam Smith Institute in the UK which calls itself the “leading libertarian think tank” which “engineers policies to increase Britain’s economic competitiveness, inject choice into public services, and create a freer, more prosperous society”. Heavy stuff!

As an aside, I wonder what Adam Smith would think if he saw these libertarian fanatics using his name in vein. I never liked much of what Smith wrote but his weave is considerably more complex than the approach taken by the free-market zealots at “his” institute.

The article – An Economic Responsibility Act for Britain – carried the sub-title “(t)he problem for democracy is not how to choose leaders, but how to restrain them”. You can see a more elaborate version of the same nonsense HERE.

Butler claims that it is in the best interests of nations if “governments were properly restrained in the first place”. He lauds the move made in the early 1990s as the neo-liberal reform agenda was ravaging New Zealand. He says:

Thanks to former Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Donald Brash, many countries adopt inflation targeting, and world inflation has plummeted from an average of nearly 30% in the early 1990s to just 3% today. We need the same sort of idea to control government spending and borrowing too.

I dealt with Brash and his New Zealand disaster in this blog – The comeback of conservative ideology. I noted that at the height of their blind devotion to inflation targeting and scrapping the welfare system there were outbreaks of tuberculosis in secondary schools in the working class suburbs and children coming down with ricketts, a disease arising from malnutrition and poverty, which was largely solved in the advanced world.

Moreover when you study the inflation targetting literature you find that the claims about its effectiveness in disciplining inflation are grossly exaggerated. As I explain in this blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – the evidence is clear – inflation targeting countries have failed to achieve superior outcomes in terms of output growth, inflation variability and output variability; moreover there is no evidence that inflation targeting has reduced inflation persistence.

Other factors have been more important than targeting per se in reducing inflation. Most governments adopted fiscal austerity in the 1990s in the mistaken belief that budget surpluses were the exemplar of prudent economic management and provided the supportive environment for monetary policy.

The fiscal cutbacks had adverse consequences for unemployment and generally created conditions of labour market slackness even though in many countries the official unemployment fell. However labour underutilisation defined more broadly to include, among other things, underemployment, rose in the same countries.

Further, the comprehensive shift to active labour market programs, welfare-to-work reform, dismantling of unions and privatisation of public enterprises also helped to keep wage pressures down.

Anyway, Butler thinks it is good for us if we extend the constraints on the use of economic policy. He claims that the Stability and Growth Pact rules that exist in the EMU are too lenient and are largely ignored.

I note this is becoming a common theme and some commentators on my blog have also questioned whether they are binding. Clearly they are not binding because the limits have been exceeded often. I read somewhere that 51 per cent of observations on public deficits since the EMU began exceed the 3 per cent of GDP rule.

But the point is not that they are exceeded. The real issue is that they are used to dictate the direction and magnitudes of the policy shifts demanded if they are exceeded. That is why they are important and damaging to national policy.

Butler wants to go further and claims the UK needs “something more akin to constitutional limits on government budgets – our own Saakashvili-style Economic Responsibility Act”. The reference to Saakashvili (Georgia President) relates to that nation’s harsh fiscal rules.

Accordingly, Butler lists 6 new rules. First, he wants to “cap public spending at one-third of GDP” and says:

Forget the Keynesian argument that a shrinking economy needs the “stimulus” of public spending. That’s like taking blood from one arm of a dying patient and putting it in the other. For every job saved, at least another is lost. And spending caps would prevent politicians setting off boom and bust cycles in the first place.

So he believes as a religious article of faith that there is complete crowding out in the labour market and therefore a multiplier of zero. No empirical research worth anything has found that result.

Further, he has no conception of the relationship between the government and the non-government sector to think that government net spending just recycles demand. You will see if you read this suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – that government net spending and reserves to the non-government sector.

Second, he would “cap deficits at 3% of GDP, and stick to it” which shows he doesn’t understand that the public deficit outcome is an ex post result dependent on private spending (and saving) decisions and external balances. There is nothing sacrosanct about 3 per cent. Even under general conditions of ECB austerity since the EMU began the 3 per cent rule has been violated often because of the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

Third, he wants to cap public “debt at 40% of GDP” because “(i)nternational rating agencies are comfortable with debts of 40%”. So with an independent central bank (unelected and unaccountable) and fiscal policy ultimately capped by what the “international rating agencies” think there isn’t much room for democracy in Butler’s UK.

I find it ironical that the freedom mongers have very limited appreciation of what freedom actually is. Allowing the unemployed to be “bullied” by amorphous bond markets is not a path to freedom.

His fourth relates to independent costing of “off-the-books obligations” and the requirement that they be fully funded. And thereby revealing he doesn’t realise that a sovereign government does have to fund any of its spending.

Fifth, he wants “independent panel of economists, like Britain’s new Office of Budget Responsibility” to allocate borrowed funds to true investment projects only. Another blow for democracy.

Finally, he want to force “public referendums” before taxes can be increased with many types of taxes banned.

The thing I am noting now in the public debate as is it unfolding three years or so after the crisis began is that there is growing denial that fiscal policy actually did anything to stop the meltdown.

I guess all the conservative fiscal policy haters who lay low as the world according to them (that is, the overly deregulated world they had pushed for over the last few decades) was going south fast, have been working on plans to make their comeback. The latest evolution is the denial that fiscal policy matters again and therefore the blithe advocacy of harsh fiscal rules as if they would not constrain economic growth and worsen private spending collapses.

Monetary or fiscal policy?

This theme sort of came up in the WSJ today (May 26, 2010) in two articles. The first article – American Jobbery Act -claims in relation to new Budget discussions in the US at the moment, that:

Sander Levin, the new Ways and Means Chairman, calls this exercise the American Jobs and Closing Tax Loopholes Act. Mr. Levin has waited 28 years to ascend to this throne and this is the best he can do? “Jobs” were also the justification in February 2009 for the $862 billion stimulus that has managed to hold the jobless rate down to a mere 9.9%. Maybe Mr. Levin’s spending can hold it down to even greater heights.

Apart from the nasty insinuation about the carer of this gentleman (Levin), what other point is being made? Is a $862 billion stimulus “big” or something? Big in relation to what? There is no sense in talking about absolute nominal spending figures.

MMT tells me that the $862 billion was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate down below 9.9 per cent and sufficient to stop it rising higher than that. It is clear that the spending gap in the US was so much larger than anyone initially guessed that the budget plans were deficient. Not to mention the fact that the terrorists were continually yelping at the heels of the Government to modify their injection.

The rest of the article is a diatribe about so-called “unfunded” spending plans (that is, within revenue) that will just blow out the public debt even further.

The other article – Japanese Lessons for the Fed – was in contradistinction.

The author noted that the US central bank chairman Ben Bernanke was in Tokyo yesterday at a Bank of Japan conference (more about which later) and should take a lesson from Japan while he is over there. The lesson? That monetary policy has limited scope to deal with a major spending collapse which then evolves into an entrenched period of deflation.

The article says (with reference to the BOJs quantitative easing experiments):

The Japanese helicopter is running out of fuel. For the better part of 15 years, the BOJ has tried everything it can possibly think of to coax more growth and rising prices, including its zero-interest-rate policy; buying commercial paper, bonds and stocks; cramming capital into banks; and various short-term lending facilities. On Friday the BOJ floated one more idea: lending banks an as-yet-undetermined amount of money at the current benchmark interest rate (now at 0.1%) to support lending that “strengthens the foundations of economic growth”-basically, productive investments.

The emphasis on monetary policy is consistent with the dominant themes in this neo-liberal era – that fiscal policy should be passive and monetary policy should be the primary counter-stabilisation tool.

However the author notes that “Japan’s banks are not facing a liquidity shortage” and that “Japan’s economy is so weak that there aren’t enough companies that need capital to finance growth”.

While the author is still in the mainstream mould, the point is totally consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Commercial banks create deposits when they make loans and get the reserves later. Their propensity to make loans is constrained by the number of willing and credit-worthy borrowers. End of story.

So given that experience, what advice is forthcoming for the US Fed chairman?

… for an economist who has famously examined Japan’s lost decade to avoid a recurrence in America, Mr. Bernanke could usefully come away from his Tokyo sojourn with a few updated lessons in mind. The most important message he could spread when he gets back to Washington is that for all monetary policy’s importance, it’s no substitute for pro-growth fiscal and regulatory policies.

Q.E.D.

There is overwhelming evidence to support the case that fiscal policy was effective in the recent downturn in putting a floor in the spending collapse. This viewpoint permeates the IMF’s official position down through various central banks and treasuries and is well-grounded in empirical research.

Anyway, this led me to read the speech that Bernanke gave in Tokyo yesterday because it relates back to the discussion earlier about central bank independence and the need to have as little policy freedom for governments as possible. So the theme reconnects.

Ben Bernanke in Tokyo

US central bank chairman Ben Bernanke gave this speech – Central Bank Independence, Transparency, and Accountability – to the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies International Conference, hosted by the Bank of Japan in Tokyo yesterday (May 25, 2010).

He began by noting the extent to which central banks around the world intervened to overcome the financial instability and arrest the spending collapse as the crisis unfolded.

He then turned to one of the themes that is around at the moment. The neo-liberals (such as the Peter G. Peterson Foundation) are arguing that so-called central bank independence is going to be compromised by governments bulging with debt. Allegedly, governments will force the central banks to inflate the economy and/or “monetise” their deficits to reduce the public debt ratios.

On this, Bernanke said:

In undertaking financial reforms, it is important that we maintain and protect the aspects of central banking that proved to be strengths during the crisis and that will remain essential to the future stability and prosperity of the global economy. Chief among these aspects has been the ability of central banks to make monetary policy decisions based on what is good for the economy in the longer run, independent of short-term political considerations. Central bankers must be fully accountable to the public for their decisions, but both theory and experience strongly support the proposition that insulating monetary policy from short-term political pressures helps foster desirable macroeconomic outcomes and financial stability.

Central bank independence (CBI) refers to the freedom of monetary policy-makers to set policy without direct political or governmental influence.

The idea took hold in the mid-1970s as the neo-liberal onslaught began to dominate policy-makers. This dominance was consolidated by the early 1980s. It was time when the OPEC oil price rises had not worked their way out of cost structures around the world and inflation was still an issue.

The central bank independence push was based on the Monetarist claims that it was the politicisation of the central banks that prolonged the inflation (by “accommodating” it). The arguments claimed that central bankers would prioritise attention on real output growth and unemployment rather than inflation and in doing so cause inflation.

The Rational Expectations (RATEX) literature which evolved at that time then reinforced this view by arguing that people (you and me) anticipate everything the central bank is going to do and render it neutral in real terms but lethal in nominal terms. In other words, they cannot increase real output with monetary stimulus but always cause inflation. Barro and Gordon (1983) ‘A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural Rate Model’, Journal of Political Economy, 91, 589-610 – was an influential paper in this stream of literature. It is highly flawed but that is another story.

But underlying the notion was a re-prioritisation of policy targets – towards inflation control and away from broader goals like full employment and real output growth. Indeed, whereas previously unemployment had been a central policy target, it became a policy tool in the fight against inflation under this new approach to monetary policy.

This leads us to consider the NAIRU underpinnings of CBI. Bernanke argues that the justification for CBI relates to the “consequence of the time frames over which monetary policy has its effects”. Thus:

Because monetary policy works with lags that can be substantial, achieving …. [price stability] … requires that monetary policymakers take a longer-term perspective when making their decisions. Policymakers in an independent central bank, with a mandate to achieve the best possible economic outcomes in the longer term, are best able to take such a perspective.

Whether monetary policy is effective or not is another question. But the logic the mainstream believe in as an article of religious faith is that by controlling prices they maximise output over the long-run. In other words they are obsessed with the NAIRU concept. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point.

As an example, in the 1996 Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, issued by the Australian Treasurer and Reserve Bank Governor set out the independence charter for the RBA and elaborated the adoption of inflation targeting as the primary policy target. The 1996 Statement said the RBA:

… adopted the objective of keeping underlying inflation between 2 and 3 percent, on average, over the cycle … These objectives allow the Reserve Bank to focus on price (currency) stability while taking account of the implications of monetary policy for activity and, therefore, employment in the short term. Price stability is a crucial precondition for sustained growth in economic activity and employment.

The rest of the text emphasised the need to target inflation and inflationary expectations and the complementary role that “disciplined fiscal policy” had to play. Price stability in some way generates full employment, which they define as the NAIRU. Of-course, in a stagflationary environment if price spirals reflect cost-push and distributional conflict factors, such an approach can surely never work. So the RBA will always control inflation by imposing unemployment.

How does the RBA answer this apparent contradiction? The RBA says that it is sensitive to the state of capacity in the economy when it pursues a change of interest rates aiming at the inflation target but that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment is not a long-run concern because, following NAIRU logic, it simply doesn’t exist.

Ultimately the growth performance of the economy is determined by the economy’s innate productive capacity, and it cannot be permanently stimulated by an expansionary monetary policy stance. Any attempt to do so simply results in rising inflation. The Bank’s policy target recognises this point. It allows policy to take a role in stabilising the business cycle but, beyond the length of a cycle, the aim is to limit inflation to the target of 2-3 per cent. In this way, policy can provide a favourable climate for growth in productive capacity, but it does not seek to engineer growth in the longer run by artificially stimulating demand.

As I noted above – the evidence is clear – inflation targeting countries have failed to achieve superior outcomes in terms of output growth, inflation variability and output variability; moreover there is no evidence that inflation targeting has reduced inflation persistence.

And in the related blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – I provide the evidence to show that the real effects (so-called sacrifice ratios) remain high whether you target or not. In other words, this era of monetary policy dominance has not delivered anything like full employment.

Central banks operating under this charter have forced the unemployed to engage in an involuntary fight against inflation and the fiscal authorities have further worsened the situation with complementary austerity.

Bernanke compares his preferred CBI to the case where “a central bank subject to short-term political influence” and:

… may face pressures to overstimulate the economy to achieve short-term output and employment gains that exceed the economy’s underlying potential. Such gains may be popular at first, and thus helpful in an election campaign, but they are not sustainable and soon evaporate, leaving behind only inflationary pressures that worsen the economy’s longer-term prospects. Thus, political interference in monetary policy can generate undesirable boom-bust cycles that ultimately lead to both a less stable economy and higher inflation.

So if you ever thought that Bernanke wasn’t a 100 per cent mainstream New Keynesian who believed in long-run neutrality (the inability of monetary policy to influence the real growth in the long-run) then that statement will disabuse you of that leaning.

What is the evidence that CBI delivers superior inflation results?

The so-called Cukierman index of CBI is widely used and “assesses the fulfillment of 16 criteria of political and economic independence using a continuous scale from zero to one, with higher values also indicating higher CBI. The overall index is based on a weighted average of the individual criteria” (Source)

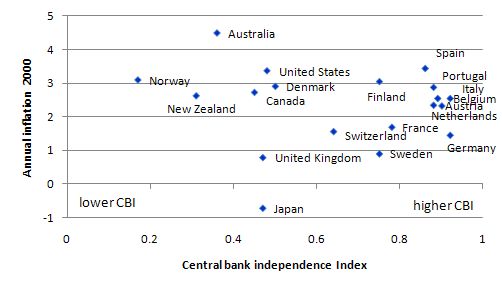

The following graph uses the values of the CBI index for the year 2000 and plots inflation against it for various countries. This is not a robust test of the hypothesis but visually nothing is happening to suspect that nations with more CBI (as measured) have lower or higher inflation rates.

The more robust empirical work on the subject delivers mixed results and the methodologies are highly compromised. First, they usually cannot control for other factors which might explain differences in inflation performance across countries. Studies that have gone to some trouble to introduce credible control factors typically find no role for CBI in controlling inflation.

Second, there are the so-called endogeneity problems. The studies tend to treat the CBI index value as exogenous (that is, given and not influenced by other factors in the models). It has been shown that nations that have high levels of “measured” CBI also introduce policies that focus on austerity. In other words, if the political factors supporting the push for austerity were absent, you would not get any traction by making the central bank independent.

The conclusion that I have reached from studying this specific literature for many years is that there is no robust relationship between making the central bank independent and the performance of inflation.

Bernanke went on to talk about credibility – another one of those mainstream jargon tools used to whip democratic decision making. He says that:

However, a central bank subject to short-term political influences would likely not be credible when it promised low inflation, as the public would recognize the risk that monetary policymakers could be pressured to pursue short-run expansionary policies that would be inconsistent with long-run price stability. When the central bank is not credible, the public will expect high inflation and, accordingly, demand more-rapid increases in nominal wages and in prices. Thus, lack of independence of the central bank can lead to higher inflation and inflation expectations in the longer run, with no offsetting benefits in terms of greater output or employment.

First, he claimed earlier (correctly) that “monetary policy works with lags that can be substantial”. This is because it operates, principally, via changing short-term interest rates, which then have to feed through the term structure, and then interest-rate sensitive spending decicions have to change. There is huge uncertainty involved because a rising interest rate helps some and hinders others. There is very little robust work that has been done to show categorically that the winners are overpowered by the losers (so rising interest rates stifle demand).

But the point is, how effective will “short-run expansionary policies” be if there are substantial lags.

Second, at present the expansion of bank reserves has been quite a characteristic of the monetary policy response to the crisis. This expansion has violated all the mainstream beliefs – erroneous as they are. It hasn’t been inflationary. It hasn’t increased bank lending. The sky hasn’t fallen in!

So given we have been experiencing this quite fundamental shift in central bank balance sheets for nearly 3 years now, why haven’t private agent expectations adjusted so that they are demanding “increases in nominal wages and in prices” to insulate themselves from inflation? Answer: Bernanke’s view is consistent with RATEX which has no empirical content at all. It is a far-fetched theory devised by ideologues to hide their contempt for government intervention in some “hard” mathematics.

Bernanke then brings in the bazooka:

… a government that controls the central bank may face a strong temptation to abuse the central bank’s money-printing powers to help finance its budget deficit …. Abuse by the government of the power to issue money as a means of financing its spending inevitably leads to high inflation and interest rates and a volatile economy.

This is the reason governments should directly control the central bank to avoid issuing debt. The point is that it is the act of net spending in a fiat monetary system that drives aggregate demand and exposes fiscal policy to the risk of inflation. The monetary operations (the central bank liquidity management) do not increase or reduce this risk.

So if the government just leaves the net spending impact on the cash system as reserves (earning nothing) that doesn’t increase the risk of inflation resulting from the spending in the first place, relative to if they drain those reserves by offering an interest-bearing public bond.

From a conceptual perspective it is important to understand that a budget deficit records a flow of net spending. It is not a stock. So when we see a figure 3 per cent of GDP, that just says that the flow of net public spending in a year (or whatever) was 3 per cent of the flow of all spending.

With the current voluntary obsession with issuing public debt – the flow adds to the stock of public debt at the end of each period. If you didn’t issue debt the stock arising from the flow would manifest as increased bank reserves. Would the treasury care about that? Why would they?

From a MMT perspective, the concept of CBI is anathema to the goal of aggregate policy (monetary and fiscal) to advance public purpose. By obsessing about inflation control, central banking has lost sight of what the purpose of policy is about.

This analogy by Henry Liu is clever in this respect:

Central bankers are like librarians who consider a well-run library to be one in which all the books are safely stacked on the shelves and properly catalogued. To reduce incidents of late returns or loss, they would proposed more strict lending rules, ignoring that the measure of a good library lies in full circulation. Librarians take pride in the size of their collections rather than the velocity of their circulation.

Central bankers take the same attitude toward money. Central bankers view their job as preserving the value of money through the restriction of its circulation, rather than maximizing the beneficial effect of money on the economy through its circulation. Many central bankers boast about the size of their foreign reserves the way librarians boast about the size of their collections, while their governments pile up budget deficits.

The point is that under the CBI ideology, monetary policy is not focused on advancing public purpose. Fighting inflation with unemployment is not advancing public purpose. The costs of inflation are much lower than the costs of unemployment. The mainstream fudge this by invoking their belief in the NAIRU which assumes these real sacrifices away in the “long-run”.

Bernanke later on in his speech addresses the degree of independence:

I am by no means advocating unconditional independence for central banks. First, for its policy independence to be democratically legitimate, the central bank must be accountable to the public for its actions. As I have already mentioned, the goals of policy should be set by the government, not by the central bank itself; and the central bank must regularly demonstrate that it is appropriately pursuing its mandated goals.

Sure, but when does the public get to elect the central bank board? And with interest rates playing the bogey person role in modern economies given the dependence in the private sector on debt, changes in monetary policy carry political messages for that the government has to sanitise.

The point is that this approach to policy-making forces fiscal policy to adopt a passive role. If it doesn’t then it will be seen to be working against the rigid application of the monetary policy rules. The consequences of that have been the persistent labour underutilisation that has plagued advanced nations for 35 years even during periods of economic growth.

Conclusion

This speech is another indication that the policy approach that took us into the crisis will remain largely intact along the road to the next crisis. Monetary policy will remain the dominant counter-stabilisation tool, despite the uncertainty about whether it actually is very effective, and fiscal policy will become passive again.

The pools of underutilised labour resources will remain high for years to come as a result of this policy mix.

If I was in charge I would merge the central bank with the treasury, release thousands of bright former central bankers via retraining into the workforce to use their brains doing something useful, and also dismantle the public debt issuance machinery.

Fiscal policy would become the dominant tool and short-term interest rates would be set at zero. Please read my blog – The natural rate of interest is zero! – for more discussion on this point. I would control inflation via a Job Guarantee.

But I will write about that structural reorganisation idea another day.

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill: You argue that it is Central Bank Independence (CBI) that has an undesirable deflationary effect. I disagree. I suggest Bernanke and Mervyn King, etc are well aware of the need expand employment.

As to Bernanke, he is constrained by deficit terrorists, who would be there even if there were no CBI the U.S. As to Mervyn King, he is in charge of a smaller currency, and is subject to whims of those, cowboys and chancers commonly known as “the markets”. (e.g. the rating agencies to which Warren Buffet pays absolutely no attention).

In your attack on the Royal Bank of Australia, you claim they think that “Price stability in some way generates full employment, which they define as the NAIRU”.

No one to my knowledge has suggested that “price stability in itself brings full employment”. To be more accurate, there IS a transmission mechanism via which in the long run full employment is brought without expansionary monetary or fiscal policies: Say’s law. But as Keynes said, in the long run we are all dead. Quite right: that is I think Say’s law works too slowly.

Also I think it is misleading to suggest anyone thinks that NAIRU equals full employment. That is ONE definition of full employment. But those of us who accept the basic idea behind NAIRU are well aware that at NAIRU there are still loads of people unemployed, and that ideally we need to do something about this. (E.g. I favour the Job Guarantee, but I think there is a better alternative, namely temporary subsidised work with existing employers rather than on WPA or JG type projects.)

Funny Bernanke’s inflation expectation theory is!

It literally means that before leaving for work, everyone updates their program which gathers all the information released by statisticians, make inflation expectations on their way to work and drop an outlook request to their bosses for a meeting after reaching the work place and bargain for higher wages depending on the data released on the balance sheet of central banks.

This is a bit off-topic, but I wonder if there is any correlation to the size/composition of deficits and country wealth concentration. The (very) basic thinking here is that during a contraction with the need to convert paper assets into liquidity to meet debt obligations, the extent to which paper assets are concentrated will extend the time needed to clear debt and require large deficits to offset the slower velocity. The composition of the deficits will shift from spending to liquidity backstops.

The size of the actual stimulus portion of increased “spend” in the US seems to me to be relatively small – but the total numbers of deficit are huge (nominally, but still). For example, it is common in the public mind to combine liquidity backstops with deficit spending – if this is incorrect (as I believe), what is an alternative context that could resonate?

Sometimes I think in our defense of deficits, we end up accidentally justifying spending that really isn’t spending, but is commingled with stimulus. This is somewhat similar to Edward Harrison’s argument that the politics are so corrupt that a useful stimulus cannot be structured. I am not ready to accept that; it might be helpful to have some metrics to decompose the deficit (beyond structural and cyclical) into functional categories.

The name “Adam Smith Institute” is a joke. I sent them months ago a letter, that it might be appropriate to change their name to something along the line “The Old Austrian Economics Institute”. Good old Adam Smith would be delighted to hear about that name change and finally stop rotating in his grave. And second a new “The Old Austrian Economics Institute”would gather much more audience applauding to the new found wisdom by Butler and colleagues.

Some readers here might consider to sign a petition cooked up by the Paolo Sylos Labini Associazione: Manifesto for freedom of economic thought – Against the dictatorship of the dominant theory and in favour of a new ethic. http://www.syloslabini.info/online/?page_id=1322

PS: Bill: Don’t worry! It’s the English Version and not the Italian one 😉

Pebird: I don’t see why “concentration” should “extend the time to clear”. The amount of deficit required for “liquidity backstops” seems to me should be roughly the same as in a less concentrated scenario. (I assume that by liquidity backstops, you mean the likes of “lender of last resort” offers by governments to banks). To illustrate, given a bank in a given amount of trouble, I don’t see it makes much difference whether than bank caters for a small number of millionaires, or a much larger number the less well off folk. Or again, I don’t see much difference between X people in possession of $Y of dodgy assets and in contrast, 2X or 3X people in possession of $Y of dodgy assets.

Re your claim that it might be helpful to decompose the deficit, I am 99% sure this has been done in most countries. I.e. there a figures out there for amount of deficit spent on actual goods and services, and in contrast, the amounts given / lent / guaranteed by governments for banks etc. But remember one is not comparing like with like. E.g. When the UK’s finance minister, Alistair Darling made £60bn available to RBS and HBOS in late 2008, this was a “stroke of the pen” creation of what you might call “hypothetical or potential money”. If little or none of it was actually used, that is totally different to creating and actually spending £60bn on real goods and services.

Food for thought.

Imperfection is definrd by its criteria of a) asymmetry, b) heterogeneity, c) disintegration and d) dispersion. Let us deal with asymmetry and reserves transactions between the CB and the banks.

An asymmetry of advantages implies unbalanced scarcity of secure resources(reserves) that bounds practices (settlements) and unbalanced danger of estimates of value (interest) that bounds decisions. For example, a buyer/investor/bank that funds complex settlement arrangements of performance and forward delivery of payment promises has an inferior (ex ante) estimate of performance (issue of diversity) and an inferior (ex post) resource(reserve) constraint of delivery (issue of evasion) than the seller/issuer/CB who knows more about performance of settlement and can control approximately forward delivery of payment. Thus asymmetry implies that the price(interest rate) is set by the seller/issuer/CB, not neccessarily equal to the notional value of the buyer/investor/bank and the quantity (reserves) is set by the the buyer/investor/bank, also not neccessarily equal to the notional level of resources(reserves) and requirement of the seller/issuer/CB. This is the effective determination of reserves, given asymmetry (one source of the imperfect structure of market interaction) and corresponds to the deposit/credit level by the banks for a given target rate of interest set by the CB.

“But I will write about that structural reorganisation idea another day.”

Look forward to that Bill

While awaiting Bill’s presentation on his overall re-organization plan for what he calls the public sector of the economy, I feel confident from the basic sketch given here that were he, in fact, in charge, then I could park this keyboard and go sailing.

Ever upward, Mr. Mitchell.

“If you didn’t issue debt the stock arising from the flow would manifest as increased bank reserves. Would the treasury care about that? Why would they?”

Maybe they would. Maybe they wouldn’t.

But the flow manifests itself as more than increased bank reserves. It manifests itself as increased bank deposit liabilities as well. These two things have different characteristics in terms of their monetary effects. The effect of additional bank reserves on bank lending should be zilch, as explained by MMT. The effect of additional bank deposit liabilities on non-bank behaviour could be quite different. MMT always seems to run the scenario where only banks are involved in such flows and not address potential non-bank effects.

Let’s call central banking what it really is, the very, very few spoiled and rich using cheap labor and cheap debt to “steal” the real earnings growth and retirement of the lower and middle class using price inflation targeting as an excuse.

Anon,

When the government deficit spends, it can increase the level of household and business deposits. This level is a function of planned expenditures, so more business sales and fewer jobless households, and higher levels of expenditures generally will result in somewhat higher deposit levels. Technology can result in lower levels of deposits. Really the level of deposits held by the non-financial sector is endogenous.

When the government sells bonds, that level does not change. I.e. no one decides to change their expenditure plans and therefore hold more or less money in deposit accounts.

All that changes is the amount of cash backing those deposits.

Households don’t care whether their deposit accounts are backed by 5% cash or 20% cash. The financial system will care, though.

I agree that not-selling bonds has other effects. I’m primarily concerned about the effect on broker dealers, who will not have safe assets to short when they go long private sector debt, and also the effect on banks, who will have fewer safe assets to hold against their short term liabilities. I think in both cases, this will put downward pressure on credit expansion, or at least make balance sheet expansion more expensive. This may or may not push up yields.

But how this actually plays out will depend greatly on the details of the overall financial architecture. Any attempts to not sell bonds must be accompanied by a re-working of the financial architecture, otherwise the lack of riskless assets will put dramatic downward pressures on business debt issuance. The proposal should be evaluated as part of an overall package, since whether it is harmful or beneficial will depend on other factors.

@anon: How will the reserves manifest as increased deposit liabilities when you havent lent at all? I mean arent all these reserves excess in that sense.

Bill,

For posterity, you should change “The models are useful in describing the real world, have no credible empirical content ” by inserting a negation 🙂

Vinodh.

I think Anon is arguing that the deficit spending will cause the deposit liabilities to increase, and that a system drain (of cash) will cause the household deposit liabilities to decrease. A system drain will certainly cause the inter-bank liabilities to decrease, but it should not cause deposit liabilities held by households or non-financial businesses to decrease. This is ignoring any interest rate effects, of course.

Thanks for the clearification RSJ!

Dear RSJ at 3:17

Thank you.

best wishes

bill

You’ve all completely missed the point of my question. Moreover, you don’t seem to appreciate the full difference between the two flow of funds scenarios, which is a bit stunning. I’ll leave it at that, since the meaning should have been self-explanatory.

“the point of my question”

I mean of course my comment; there was no question actually

Banks have a liquidity pressure and government securities help them. In the US, banks have less government securities because they consider(ed) agency debt and agency mortgage backed securities as almost equivalent. In the Euro Zone, securitization is/was hot, but not as big as the US and the banks hold more government securities. It helps them build their “own funds” as well.

In Bill’s proposal, banks don’t face liquidity pressures because the central bank doesn’t need collateral and can lend them in unlimited quantities.

As far as deposits are concerned, one is worried about this fact: If deposits are not drained by government securities, and the private sector doesn’t desire to hold so much what happens ? The answer is that the private sector will purchase other securities and the issuer will reduce its debt to the banking system. A production firm can either borrow from the bank or through equities. This may look like an independent process – however it is not.

I remember RSJ mentioning in another post that it may put an upward pressure on equities – I think he has a point.

Bill,

If you ever come across Scott Sumner’s “NGDP futures market” idea, it would be a very good opportunity for you to debunk a completely crazy monetary policy proposal, and very interesting to see your analysis on it

Dear anon

I have seen it and I just sort of gave up on it. I might review that decision and see if there is something in it to interest everyone.

best wishes

bill

Ouch. But if you seriously believe that not selling bonds will cause the non-financial sector to hold excess deposits, then I think you are the one who doesn’t understand this flow. And this is not up to debate — go look at non-financial deposits in Japan. Deposits remained constant (and were falling slightly) even as the monetary base swelled. The only change that occurred was that there was more cash backing each non-financial deposit.

There is an ongoing debate on CB ops over at Warren’s here. It’s a long thread, over 500 comments and still continuing. Many knowledgeable contributors have chimed in. Anon, Ramanan and Scott’s comments on the Eurozone have been particularly detailed in their back and forth, with Warren jumping in occasionally.

Summer’s NGDP idea strikes me as wagging the dog’s tail (but what do I know). It would be interesting to get Bill’s take on it, if he thinks it worthwhile to pursue.

It would be the creme de la creme take down of monetarism (or whatever its called).

The proposal is an outrageous implementation of the multiplier fallacy, on steroids.

Something to think about.

The ECB has entered the secondary market for EU member bonds and its purchases, although it does not change NFA and net worth of market participants, due to the asset swaps and the presence of excess reserves relative to bonds it has caused the euro to depreciate, so there is an exchange rate effect from secondary market purchases. A lower exchange rate for the euro COULD induce inflationary expectations in anticipation of more costly imports and of course higher exports.

“MMT tells me that the $862 billion was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate down below 9.9 per cent and sufficient to stop it rising higher than that. It is clear that the spending gap in the US was so much larger than anyone initially guessed that the budget plans were deficient.”

AS I recall, Christina Romer first floated 1.5 trillion for the stim and actually proposed 1.2 trillion, mostly spending. The WH chopped it down to 862 billion, with about a third of it going to tax cuts (reducing the multiplier), in the hope of bringing some Republicans on board, who never came. There were people in the WH warning that the stim was too small and ill-concieved right from the get-go. The president took bad advice and blew it, apparently looking for conservative votes that he did not get. Now he is in trouble, facing a double-dip going into a tough election in which he could lose control of Congress.

“MMT tells me that the $862 billion was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate down below 9.9 per cent”

Then MMT is wrong. 200 Billion would be more than enough to fully employ all 7 million people who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more, paying them healthcare and $12/hr full time. That would have brought the long term unemployment rate to zero. More money would have brought the ST rate down to zero. The additional tax revenue raised could more than pay for program administration.

Therefore if your theory says that spending 860 billion is not enough, your theory is wrong. There are demand leaks — that money is being used to boost profits and is not going to increase hiring. This is always a risk whenever there is slack in the economy, and your theory needs to take account of that.

Trying to draw a simple causation between the amount of deficit spending and a decrease in employment is not going to work. There is *no* amount of deficit spending that will result in full employment, unless you specify that the deficit spending be used to directly hire the unemployed. And in that case, 1/3 of the current stimulus could have brought unemployment to zero.

There is no mechanism that will force a firm to hire someone if they are faced with increasing purchases. They will hire someone in China first, and then they will hire someone in Guatamela. Only after you have drained the ocean will you be able to guarantee full employment simply by deficit spending.

That is why the full employment governments of the 1950-1970 period did not run large deficits — they did not need to, since the high tax rates drained back most of the demand leaks. Those governments would have been horrified at the suggestion that you need to flood the private sector with money in the hopes that out of patriotism, someone will get hired. Flooding the private sector with money primarily causes more inequality, and is not an effective tool to reduce employment. Direct hiring of the unemployed is.

Ramanan,

I don’t think you should be worried about that.

In general, attempts to count money like this will lead you to the wrong conclusion. A better, simpler, way of looking at this is to imagine that households wish to hold assets with certain characteristics (e.g. maturity, risk profile), and that borrowers wish to issue liabilities with different characteristics. In that case, the financial system intermediates and is able to supply households with the types of assets that they wish to hold, while allowing liability issuers to sell the types of liabilities that they wish to hold.

If there were, say, a shortage or safe debt and an excess of risky debt, then households would be willing to overpay for one, and underpay for the other, and this creates a profit opportunity for the financial system to buy the risky debt and issue safe debt to households, pocketing the premium. This holds for whatever characteristics you care about: e.g. maturity, volatility, duration, etc. The financial system is able to supply substitutes to households so that their asset desires are fulfilled regardless of the types of liabilities that are issued.

So just always assume that the non-financial sector holds exactly the types of assets that they want to hold — it holds as many deposits, bonds, stocks as they want, and that the financial sector bears in its own balance sheet the discrepancy. And this applies to government liabilities as well. If the government were to issue less cash and more bonds or fewer agencies and more treasures, etc, — still household portfolios would remain unchanged, under the assumption that assets with similar maturity and risk characteristics are equivalent. The balance sheet of the financial sector would change, but not that of households. This is why government bond sales drain excess reserves from the financial sector — the sale of government bonds succeeds in changing the ratio of deposits to cash precisely because it does not decrease the level of household deposits, but it does decrease the level of cash. All these portfolio shifts — regardless of *who* buys or sells the security — end up altering the balance sheet of the financial sector, but not the balance sheet of the household sector.

Bernanke: “First, for its policy independence to be democratically legitimate, the central bank must be accountable to the public for its actions.”

He apparently does not notice that there is a fundamental contradiction between independence and public accountability. The more independent a central bank is the more it is unaccountable and antithetical to democracy. In addition, the more control that a central bank exerts over the interest rate (price of money), the more there is a command influence operating on the economy instead of markets, which is antithetical to free market capitalism. So we have unelected and unaccountable officials that cannot be removed or replaced until their terms expire presiding over monetary policy. Makes no sense in terms of fundamental the neoliberal principle that a free market is the economic foundation of liberal democracy.

RSJ, while I agree with your numbers, the stim was more complicated than that politically (which was your point, too). Some of it was to go to infrastructure (public investment) and aid to states in order to stem the inevitable cutting of key personnel, such as teachers, police and firemen. And then there was all that was necessary to get the various constituencies to go along with it, and the politicians to vote for it. That’s political reality, such as it is. Could the president have gotten a stim passed only a third as big, but which was “a hand-out” to the unemployed. No way.

@ RSJ at 14:43. Nice explanation. I had never thought of intermediation in that way. Makes it very clear.

I agree with your political analysis, Tom, although really we will never know. Obama never used his bully pulpit to call for JG, and I think that a JG would be popular if it were marketed well — particularly as a replacement for unemployment insurance. I think it would garner broad support.

But the economic analysis is what I am questioning.

You cannot just say “well the government is not deficit spending enough” — that is too simplistic. Look at what is happening now — corporate earnings are back up, but unemployment remains high. The deficit spending ended up boosting corporate earnings but not employment, and so it is not the right thing to look at.

It would be like saying that we have an obesity problem because we are growing too much food. The distribution is what counts, and you can accomplish a large decrease in unemployment with a much smaller level of deficit spending, or you can deficit spend more and make no impact on unemployment, or even increase unemployment. This is why I believe the private sector NFA obsession is harmful — it is too broad of a metric to use and does not address the key issue, which in my mind is income inequality. The JG, on the other hand, does effectively address unemployment, and if the wages are set high enough, will put upward pressure on median wages which is also a Good Thing. That combined with very high marginal tax rates would allow the government to spend to its heart’s content, keep unemployment low, and yet end up not deficit spending a whole lot. And this is exactly what happened during the full employment era of 1950-1970: private sector NFA shrank, we had full employment, rising median wage shares, and growing output. We should strive to achieve all these objectives.

Dear Tom,

The contradiction between independence and accountability that you mentioned is an important point assuming accountability means reporting. A lot of time they mean by accountability the release of ex post statistical data or even analysis for monitoring purposes but not reporting ex ante for assessment of policy. Full accountability means both. Furthermore, full accountability means responsibility for performance and removal from office something that violates independence and allows the “capture” of public institutions by private interests. The drive for technocratic agencies with independence is an attempt to impose the Platonic notion that “experts” know best.

Dear Takis,

I actually agree with the Platonic ideal of rulership of the wise, but Plato did not mean technocrats, he meant leadership by those who have realized the Good and can distinguish between what is good and the useful, as well as rise above egotism to practice “virtue” (the English translation of arete, which doesn’t capture its classical import of human excellence as self-actualization).

Contemporary technocrati are far from this, and rather than being “experts,” they are simply cronies. When they come to power, they act like cronies rather than disinterested and impartial experts, and there is no way to discipline them, remove them, or otherwise hold them accountable.

Bernanke’s use of the term “accountability” is hypocritical when the Fed as chief financial regulator has held no one accountable for decades. Alan Greenspan was a disciple of Ayn Rand and an avowed anti-regulator. There is no mechanism to require accountability, and when Congress, to whom the Fed is actually accountable, wants some accountability, then the Fed starts shouting loudly that it is a violation of its independence and an intrusion of politics that will have deleterious consequences.

What a bad joke.

“You cannot just say “well the government is not deficit spending enough” – that is too simplistic.”

Agreed. It’s a statement of principle but it requires considerable articulation. I think that this is articulation is understood around here, although perhaps not by some just arriving. MMT holds that Abba Lerner’s principles of functional finance need to be adapted to current circumstances, and one of the principle is the one relating to fiscal operations. Nevertheless, it needs to be explained also, as Bill has done in many places, that this involves targeted policy. Fiscal policy can be much more tightly targeted than monetary policy, which is a blunt and slow-acting instrument.

The problem is, as you observe, that fiscal policy has not been tightly targeted and therefore has involved a great deal of waste in the sense of money spent that was either not needed or went where it did a lot less than it could have otherwise. I pointed out that this is part and parcel of US politics, where everyone has to get something to get a bill passed and signed, and the top end has to extract a disproportionate share.

That is why I dislike omnibus bills that purport to be comprehensive, but in reality are just a way of getting the necessary votes by ensuring that all interests are compensated proportionate to their power and influence. While it would be much better to break the big bills down, most of the desirable parts would fail and the undesirable ones would pass easily. That is why we have big bills. Subsidies carry the “hand-outs.”

It’s a bad system in many respects, but that’s republican liberal democracy under neoliberal capitalism.

Hear hear for Sumner NGP idea–if you can make sense of it. As far as I can tell it’s merely a predictions market for were NGDP should be, but no mechanism to take it there.

Dear Tom,

We agree on accountability and independence. However, I thing you misunderstood my point on technocrats and experts. I said that is an “attempt” to impose the Platonic idea since according to mainstream theorists “ariston” is the rational practice of their theories. These are implemented by the technocrats as experts which means fully knowledgable of the “correct” theory of reality which is their own hypothesis and framework of analysis (spurious thinking!). By the way ariston is not the same as “arete” as the first is the ancient Greek concept of optimum (hint: different fron modern concept of extremum) and the second is excellence as a public duty subject to ethical criteria of fairness of decision and equity of praxis. These are issues analysed by my framework and I continue to develop in the document “General Framework of Occurrence” (which you have an earlier version) and not the other one I sent you on “Knowledge Management”.

You were the one who said “MMT tells me that the $862 billion was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate down below 9.9 per cent”

And over on Mosler’s site, we read in the “Mandatory Readings”:

— A patently false statement.

Nowhere in either the Mandator Readings is there any discussion of income distribution as the driver of unemployment — it solely the residual NFA that drives everything.

And those who hold to this view have a difficult time reconciling these views with the data:

When private sector NFA/GDP was rapidly shrinking in the 1950-1970 period, unemployment was low. When private sector NFA increased, so did unemployment. There is just no evidence for the belief that increases or decreases in private sector net financial assets are a cause of involuntary unemployment, although of course there is a belief that automatic stabilizers can force private sector NFA to rise as a result of increasing unemployment.

A serious analysis will not make statements like the above, but will focus first and foremost at the interplay between income distribution, sustainable rates of investment, and household net financial assets. That is what you should be talking about.

RSJ: You were the one who said “MMT tells me that the $862 billion was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate down below 9.9 per cent”

Actually, I was quoting Bill’s post, Then, I added the bit about Chirstina Romer

RSJ again: A serious analysis will not make statements like the above, but will focus first and foremost at the interplay between income distribution, sustainable rates of investment, and household net financial assets. That is what you should be talking about.

I assume that this is aimed at Bill and Warren, since I haven’t made any of those assertions.

Tom, I was not trying to attack you, but suggesting a more fruitful (and accurate) line of analysis, rather than just look at the the balance sheet of the entire private sector. The latter is not a fruitful line of analysis.

The “you” in “That is what you should be talking about” refers to anyone talking about these issues.

I would like at insert something here for the record about the global politics of central banks. it isn’t so much economics as policy agenda.

“The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent meetings and conferences. The apex of the systems was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations. Each central bank…sought to dominate its government by its ability to control Treasury loans, to manipulate foreign exchanges, to influence the level of economic activity in the country, and to influence cooperative politicians by subsequent economic rewards in the business world.” ~ Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, (1966), p. 324.

Carroll Quigley was not a conspiracy theorist but a well-known and highly respected professor of history who taught at Georgetown University in his later years. He was an “insider” and wrote approvingly of the coming “new world order” under the leadership of the “wise,” that is the technocrati, whom he genuinely believed had not only the knowledge and skill to manage global affairs but also the breadth of spirit to do so in the best interest of all. He is not writing in criticism above, but in approbation. The “hope” of which he writes as a historian of civilization is these “wise men.”

I am not asserting here what I think of this view. I am simply saying that this is an implication of central bank independence that is conscious and intentional, indeed, declared and made public by other insiders such as David Rockefeller.

Of course, this drives the conspiracy theorists into a frenzy, and I don’t want to evoke that sentiment. However, it is a dimension of central bank independence that is not separate from the financial and economic considerations, because finance and economics inevitably intersect with policy. The political implications of central bank independence are bound up with the financial and economic ones.

Saying that central banks should be independent of politics because it gives elected politicians (who are accountable to the people) is ridiculous on this score. Giving central bankers independence allows them to set the policy agenda through control of finance, and through finance, control over the destiny of the global economy and of nations and peoples. That is a lot of power for a few select people to have, considering they are not elected or accountable to the people whose lives they effectively control economically.

There are some very high stakes associated with deciding whether these are really the wise men that are the hope of the world – or not. The question is whether they are 1) wise and 2) benevolent (above class interest). If they fall short on either count, then there will be problems resulting from their political independence, considering the power they have garnered.

RSJ, I was simply replying that I am not called upon to reply since I didn’t make those statements. I happen to agree with Bill and Warren on the basic points, and I also admit that you and others make some good points that need to be addressed, which suggest that the basic points be qualified. Otherwise, it can seem that MMT is saying to just throw money to solve problems. MMT’ers may object that this is shallow and unjust criticism, but it is common, and therefore, it shows a communications gap that needs to be addressed.

For example, while it is a truism (as an accounting identity) that a government surplus equates to a nongovernment deficit in that period, and vice versa – if one accepts the sectoral balance analysis, it doesn’t necessarily follow that government “should” make up the difference if there is a non-government deficit. What MMT shows is that there is such an equation resulting from the sectoral balance approach and that using functional finance a monetarily sovereign government can offset nongovernment deficits, not “should.”

That is a policy issue that both stands in need economic justification and also involves ethical, social, and political norms. Even if it is decided that government should do this in any case, the question of how comes into play, and that also involves some complex issues. These things have been discussed since the time of the Great Depression and remain undecided. So let’s have at.

Follow up to my @ 1:22, “for the record” on the political implication of CB independence:

Former finance type turned activist Damon Vrabel lays out a detailed case in on Central Banking vs. The Republic and the World

Tom,

I think that is an excellent characterization of the issue. We expect, at the end of the day, a set of guidelines for managing the economy. The only guidelines I’ve seen so far are to deficit spend “as much as is necessary”, and I am pointing out that there are serious distributional consequences to doing this. You can spend as much as is necessary, while draining back from those who would receive economic rents, and if you do this, you will find that you are not deficit spending a whole lot. That is how we managed the economy during the “thirty glorious years” — larger levels of spending, combined with higher marginal tax rates, so that in the end deficit spending was quite small, and yet we had full employment and more income equality.

So if I had my way, MMT would disaggregate more than it does now. It would not look at the entire private sector, but at the household sector, financial sector, non-financial business sector, government and foreign sectors. And each of the above would be subdivided into income quintilies. No one would care one way or another about the NFA of the private sector, but they would care about the NFA of each income quintile, and there would be an understanding of the relationship between the cost of the capital and the return on capital. All of that should be integrated in my “ideal” economic management policy.

To do this, you would need to not only look at the clean world of accounting but also look at various models of production and capital growth, of opportunity cost, and income distribution — and as a result, more people would disagree with you.

So I understand the desire to stick to broad, simple concepts such as NFA of the private sector being responsible for demand failures, and an assumption that the FFR is somehow the determinant of inequality.

That is very simple, and if people don’t think too much about it, you will get them on board. But there are no free passes here. An economic management policy based on only looking at NFA and FFR is as likely to be harmful as it is to help. At the end of the day, you need to do economics, talk about opportunity cost, about capital growth and about distribution. I am sure that if you were to poll Bill, Scott, and Warren, they would each express somewhat different opinions about how these things work, but that is debate that needs to happen.

RSJ, in defense of the MMT’ers I have to say that they have considered many of these things in the literature, especially unemployment and the job guarantee or employer of last resort, for example. Bill has written a book on it no less. In addition, Warren has been offering his proposals for the economy as part of his political campaign, too. So I don’t think that the lack is as great as it might appear when arriving here or at Warren’s. It took me some time to find my way around, and I’ve only been at this for a fairly short time, so I haven’t even scratched the surface of the literature.

There is only so much that one can do in a blog post or a few blog posts. But Bill especially has a burgeoning archive of them. There are also plenty of working papers available free online at levy.org and cofFEE(see Links on this blog), which is a great boon for those who don’t have access to subscription journals. There are quite a few people writing papers on MMT or MMT-related who don’t blog.

Still, a lot of the economic argumentation is over the head of a lot of non-professionals (like me) and it would be nice if the MMT bloggers and pro commentators would address some of the issues that you and others raise. These are the kinds of questions that people who are interested in spreading the word on MMT need to understand and be able to address is terms that non-economists can get. So I am happy that you are asking these questions and I am looking forward to answers as the professionals get around to it, given their busy lives.

I cannot stand Libertarians !