I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader – Part 3

This is a third part of an as yet unknown total, where I investigate possible new policy agendas, which are designed to meet the challenges that Japan is facing in the immediate period and the years to come. The first two parts were written in the context of the elevation of Ms Takaichi to the LDP presidency. It was anticipated that she would then become the Prime Minister as a result of commanding a majority on the floor of the Diet, with help from long-standing coalition partner Komeito. However, in the last few days, things have changed considerably in Japan with Komeito withdrawing from the ruling coalition and throwing the question of who will become the Prime Minister up in the air. One of the issues that are shaping what happens next is the question of social security sustainability as the society ages. This divides the parties and will help to determine the configuration of the next government in Japan.

The dissolution of the ruling coalition has dealt the LDP a major blow.

It is already in decline and has been losing votes to the centrist parties.

But Komeito is also on borrowed time, given its support base is ageing and it has been unable to attract the new younger voters.

It traditionally stood between the LDP, which garners support from the wealthy, the financial markets and the large export-oriented corporations and the Socialist Party, which represents the trade unions and the welfare lobby.

Komeito represents the voters who are not aligned to these ‘extremes’ and have thus been able to garner around 6 per cent of the Lower House seats (5.2 per cent in 2024).

That has to be seen in the context of Komeito’s acceptance under the Coalition agreement not to contest LDP seats and direct their supporters in those constituencies to the LDP.

I have seen estimates that this allows around 25 per cent of LDP candidates to win their districts.

Their role in the coalition has been to moderate influence of the hardliners in the LDP who have wanted to abandon what is referred to as the Japanese social contract.

That group has ravaged welfare outlays over the last decade or more but would have gone further had it not been for the influence of Komeito.

So, in the short-run, even though Komeito is facing decay over time as its supporter base gets older, the welfare issue will shape the formation of a coalition.

It is not the only important policy issue that is now part of the horse trading going in Tokyo, but it is an important aspect.

The main players in the 465 seat House of Representatives:

- Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) – 191 seats – Nationalist but not neoliberal in economic policy.

- Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) – 148 seats – Centre-left party pro-welfare

- Japan Innovation Party = Ishin – 38 seats – Right-wing, but not opposed to welfare support.

- Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) – 28 seats – Centre-right, populist, support expansionary fiscal policy.

- Komeito – 24 seats – Centrist, social conservatism, pro welfare.

- Reiwa – 9 seats – Left – progressive.

- Communist Party (JCP) – 8 seats = progressive.

Komeito has withdrawn from the Coalition.

It is in talks with CDP to agree to a unified PM candidate.

The DPFP have refused to join a coalition with LDP or Komeito.

It also will not work with the LDP.

It is willing to coalesce with the smaller progressive parties.

The CDP is pushing for the leader of the DPFP to be a sort of unifying PM candidate.

Ishin will agree if the CDP and the DPFP agrees will the Japanese Communist Party.

How it all plays out is anyone’s guess right now but it is looking considerably less certain for Ms Takaichi.

Social welfare expenditure and the consumption tax are key economic issues that will shape the final outcome.

I will talk about the consumption tax issue in the next installment.

Population trends and dependency ratios

I last analysed the movement of the dependency ratios in Japan in this blog post – What is the problem with rising dependency ratios in Japan – Part 1? (October 28, 2019).

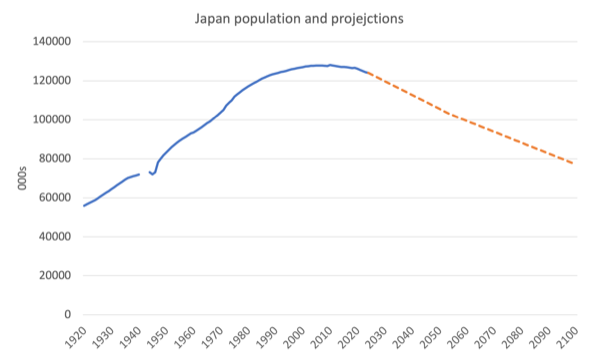

The following graph shows the total Japanese population from 1920 to 2024 (during the WW2 years (1941-43) no data was collected).

The dotted line shows the latest UN population estimates out to 2100, which are published in its annual publication – World Population Prospects 2024.

The total population has been shrinking since 2010 as birth rates decline and death rates increase. Net immigration is very low by international standards.

There are many reasons for the declining and low birth rates – sociological and economic (insecurity etc).

The 2024 population was 124,071 persons and the UN predicts by 2054 there will be 102,763 thousand persons and by 2100 there will be 77,038 thousand persons.

Previous government policies to increase the birth rates (subsidies to young families, free preschool education, etc) has not substantially changed the downward trend.

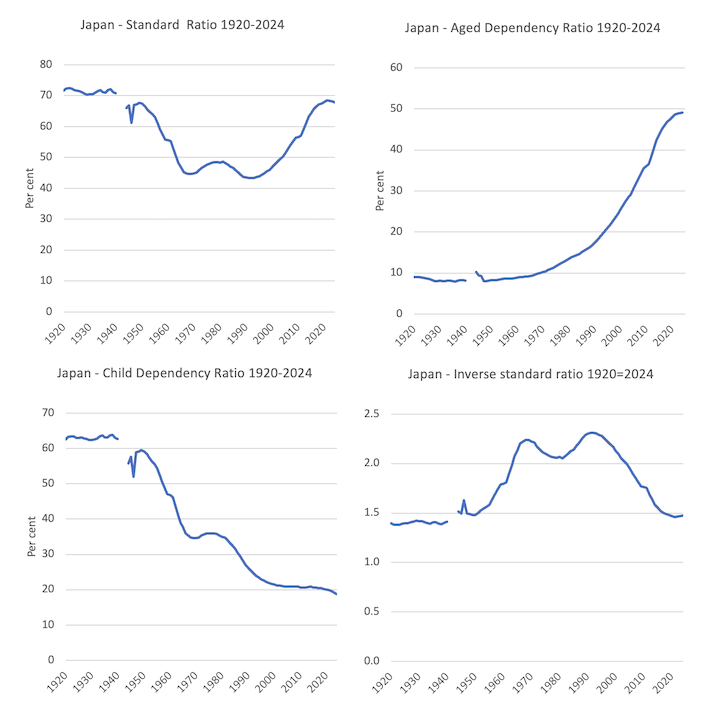

The following 4-panel graph shows the various dependency ratios for Japan from 1920 to 2024 based on a working age population of 15-64 years (even though many Japanese workers have historically retired at 60).

The inverse dependency ratio, which tells us how many productive workers there are per non-productive person in the population, peaked at 2.31 in the early 1990s and is now at 1.47.

Based on the projected data from the UN it will fall to 1.03 by 2050.

As the total population declines and ages, the dependency ratios will rise towards 70 per cent, meaning that 30 per cent of the population will have to work to support the material needs of the 70 per cent.

That will require that the younger Japanese will have to be more productive than their parents – by some margin.

The other option, which is not at odds with the productivity imperative, is that the nation accepts a lower material living standard and ensures wealth and income distributions are made less unequal to reduce the social pressure that will arise from that choice.

The so-called welfare crisis in Japan

This data has spawned catastrophising commentary in Japan and the government has reacted in the last decade with significant welfare cuts.

I was at a rally yesterday in downtown Kyoto protesting these cuts, which have left many Japanese people, particularly those with disabilities in an impoverished state.

These cuts are seen as being a breach of the Japanese social contract.

The Japanese social contract relates to the implicit understanding between the government and the citizens that the former will work to provide high levels of material security to citizens and will resist special lobbying interests that may undermine that goal.

Further, the citizens accept that social discipline is paramount in ensuring the goals are met.

There are several dimensions to this contract, including the practice of lifetime employment and the reciprocating corporate loyalty of the ‘salary men’ (and more recently women), and strong partnerships between government and the corporate sector.

The cultural concept of 義理 (giri) or social duty, honour and obligation is deep-seated here in Japan and an essential aspect of the social contract.

The contract is the antithesis of Western neoliberalism but as the ideas of the latter creep into Japanese public life, the contract is in danger of losing its traction.

The mainstream economic debate began to obsess about the combination of relative high fiscal deficits after the interventions necessary to stabilise the economy after the massive asset bubble collapse in the early 1990s and the demographic dynamics.

The growing neoliberalism (among economists not the LDP) focused on the growing social expenditure in Japan and the projections that it will have to rise to deal with the ageing society.

They also noted the rising proportion of social expenditure on aged pensions and health care.

There is no surprise there – as societies age less expenditure is required on primary schools and more is required in aged care.

But the debate focused on what is considered to be an impending fiscal disaster.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs released the transcript of a speech given on March 11, 1997 by a leading journalist – The Social Security Crisis in Japan.

The Speech is representative of the tendencies in the debate over the last 25 years.

The speaker asked his audience (a gathering at the Japanese Consulate General in Boston, US) where is the then “60 trillion yen” that the government was spending on social expenditure:

Of course, it came from the taxes and premiums paid by the general public. The government collects taxes and premiums from incomes of people and enterprises. Japan’s national income for fiscal 1994 was roughly 16% of this figure.

In other words, the Japanese public paid 16% of their income to keep the social security system going. And of course, social security is not the only thing the government — both national and local — asks the public to finance. The public must also pay for the country’s diplomatic services and defense; for new roads and railways; for public education, and to keep government employees on the payroll. The list goes on.

These expenses must be financed with tax money.

Of course, not a yen of the social security expenditure comes from tax revenue or insurance premiums, despite the cosmetic sense of causality.

The taxes that the Japanese people pay are designed to ensure they have less yen to spend, rather than giving the Japanese government more yen.

The speaker said that social security expenditure was “16% of national income” in 1997 and “will rise to 30% by 2025”.

The actual proportion in 2025 is about 25 per cent.

But there is no escaping the fact that it has risen substantially over the last few decades.

The solution proposed by the neoliberals involved cuts to “social security spending as a whole” but aged care should be expanded (given the demographic trends).

So cuts to pensions, medical care, disability support become the candidates for cuts.

The speaker concluded by delivering the usual threats:

These steps may be painful, but without them Japan’s public finances will collapse

The ‘social security crisis’ in essence is nothing to do with the financial capacity of the government.

There is no probability that “Japan’s public finances will collapse”.

The problem is not financial but real (by which I mean material).

It is possible that the working age Japanese in the coming years will not be able to produce enough to maintain the current high material standards of living for those who can not produce goods and services as a result of age.

It is possible that there will not be sufficient nurses, doctors, care workers, etc to cover the needs of the ageing population that will require increased medical care as time passes.

These are the threats.

The government will be able to provide as much aged care as is necessary if it can command the productive resources that are necessary to accomplish that task.

That is the challenge.

The solution is not to cut the income support and investments in social care.

But rather it is to ensure that the younger generations are highly skilled and have the investments in technology and infrastructure that will allow those skills to produce at high levels.

Conclusion

How this debate plays out will shape the politics of Japan and who will end up governing the country into the future.

As the horse-trading goes on in Tokyo to try to stitch a coalition together that can command a majority on the floor of the Diet, the issue of social security expenditure will play a central role.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you for this very interesting series on Japan. It provides background that I have been lacking in my understanding of Japanese politics. Fascinating.