In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Japan – the challenges facing the new LDP leader

This will be a series of blog posts where I analysis the period ahead for Japan under the new LDP leadership of Ms Sanae Takaichi. The motivation is that on November 7, 2025, the research group I am working with at Kyoto University will be staging a major event at the Diet (Parliament) Building in Tokyo where I will be one of the keynote speakers. The strategic intent of the event is to outline a new policy agenda to meet the challenges that Japan is facing in the immediate period and the years to come. It is highly likely that the Lab Director here at Kyoto, who promotes and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective and was formerly the special advisor to the Shinzo Abe, will return to that position under Ms Takaichi. This gives the event increased importance for outlining an Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)-based perspective. Today, I examine the inflation issue in Japan.

Ms Takaichi is an advocate of what became known as Abenomics, which in the era when Shinzo Abe was Prime Minister, was characterised by what was referred to as loose monetary and fiscal policy.

The characterisation really relates to his second term as Prime Minister from 2012 to 2020.

In his first period of office, which began when he succeeded the arch-neoliberal, Junichiro Koizumi, Abe advocated balanced fiscal positions through spending cuts.

Some political funding scandals within the ruling LDP prior to the 2007 election, which precipitated the suicide of his Agricultural Minister (Matsuoka), the government lost control of the upper house after 52 years of successive rule and the replacement Agricultural minister was also forced to resign in a new funding scandal.

Abe then had to replace another Agricultural minister also mired in funding scandals, and eventually was forced to resign as PM.

Abe’s second term as PM began after the December 2012 election at a time that the LDP had lost its majority in the Diet (lower house) as a result, mainly, of the decision to increase the consumption tax from 5 to 10 per cent.

Abe took over leadership of the LDP in September 2012 and his political campaign marked an about-face in terms of economic policy.

He proposed an economic growth strategy based around ‘loose’ monetary policy and expansive public spending increases.

There were other popular policies advocated (retention of nuclear energy) and the LDP won the election handsomely (in a coalition with its traditional partner the socially conservative New Komeito (NKP).

He was reported as saying (Source):

With the strength of my entire cabinet, I will implement bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy and a growth strategy that encourages private investment, and with these three policy pillars, achieve results.

This approach gave birth to the term ‘Abenomics’, although apart from some period of dallying with neoliberal policies, such as the consumption tax hikes, the LDP had been following this sort of strategy since the asset bubble burst in the early 1990s.

The shift to ‘loose’ policy saw the unemployment rate fall from its maximum of 4.3 per cent in February 2013 to 2.2 per cent at the end of his term (averaging 3.1 per cent during his period in office).

That nomenclature ‘loose’ in relation to fiscal and monetary policy is, however, rather loaded.

First, ‘loose’ monetary policy refers to a regime where low interest rates are prioritised and the central bank uses its currency-issuing capacity to purchases assets (including government bonds) in the secondary markets to push up demand and drive down yields.

There are other elements that might be accompanying those interventions (for example, cheap loans to private banks).

It implies, of course, that loose monetary policy is ‘expansionary’ (stimulus to aggregate spending) and tight monetary policy is contractionary.

This characterisation drives the Monetarist notion that inflation is ultimately the result of excessive ‘loose’ monetary policy, which allows too much liquidity (money) to circulate in the economy.

However, the reality is that monetary policy is not very effective in manipulating aggregate spending.

For example, in the case of an interest rate cut, it is uncertain whether the gains made by borrowers will stimulate more spending overall than the losses made by creditors.

Further, in times of recession or when private sector pessimism rules, firms will not invest no matter how low interest rates go, if they are uncertain of future sales.

They will wait until there is solid evidence of a sustained recovery before committing to new investments in capital plant and equipment.

It is also subject to long reaction (or time) lags because unlike the price of a good or service, interest rate changes impact on the cost of credit.

Mortgage holders, for example, may initially seek to maintain their current spending levels by drawing on pre-existing savings.

So the idea that a low interest rate regime that is continuously maintained by the central bank constitutes ‘loose’ policy is contestable.

Further, we have seen in the recent period of inflation how increasing interest rates to combat inflation, instead, drove higher inflation through its impact on rental charges, and more broadly, the cost of capital.

What we also know is that one thing interest rate hikes, for example, achieve is to redistribute income from low-income mortgage holders to high-income financial asset holders, which compounds pre-existing income and wealth inequalities.

Second, referring to a fiscal deficit as ‘loose’ fiscal policy is also problematic.

Fiscal policy should be used to ensure that total spending in the economy is sufficient to induce firms to produce at levels that will provide jobs for all who desire to work.

So fiscal policy should be designed to target (close) spending gaps left by the desire of the non-government sector to spend less than its overall income.

In that sense, depending on the non-government sector savings desire, the appropriate fiscal position will vary between surpluses and deficits.

If there is a 2 per cent of GDP non-government spending gap, then the appropriate fiscal deficit (to sustain full employment) will be 2 per cent of GDP.

Referring to that policy choice as ‘expansionary’ or ‘loose’ is misleading.

It is really a status quo choice, where full employment is the status being maintained.

Bearing that conceptual discussion in mind, there is already a lot written in the media in the last few days about how Ms Takaichi will advance ‘expansionist economic policies”, which the media define as pressuring the Bank of Japan to reduce interest rates, increasing the government deficit, and leaving the yen to depreciate (or not appreciate).

After winning the LDP presidency, Ms Takaichi said (Source):

What would be best would be to achieve demand-driven inflation, where wages would rise and drive up demand, which in turn causes moderate price rises that boost corporate profits,

That stands in contrast with the media’s characterisation of her as the new Margaret Thatcher.

She is a nationalist and ultra conservative on social policy and immigration but her economic policies will not resemble the Thatcher application of Monetarism.

She is familiar with MMT (via her advisor) and will resist the current pressure from financial markets on the Bank of Japan to increase rates further.

The commentary in Japan has shifted from a constant fear of deflation to a new (mainstream) fear of accelerating inflation.

Bank of Japan governor (Kazuo Ueda) while still maintaining a public position that firms are still not pushing wage rises through as fast as the government desired to consolidate the shift away from deflation, has also been open to increasing interest rates.

As I noted recent in this blog post – Bank of Japan’s ETF sell-off is a sideshow (September 25, 2025) – the Bank has been making very orthodox noises about returning to ‘monetary policy normality’ (whatever that is).

Mainstream economists claim that inflation is too high now in Japan and higher interest rates are required to dampen spending, once again appealing to the notion that monetary policy is effective in achieving such an aim, despite the evidence to the contrary.

The All-Groups inflation rate is currently running at 2.75 in August 2025, the lowest rate it has been for 12 months.

But most economists (not me) claim that is too high and further interest rate rises are necessary.

While I do not support the nationalist and social policy stances that Ms Takaichi and her team advance, her resistance to further interest rate rises are sensible, given the dynamics of the inflationary process in Japan.

Quite apart from the issue of the effectiveness of interest rate hikes, we are witnessing a replay of the claims made during the early stages of the recent inflationary episode which misdiagnosed the sources of the price pressures.

The only logic (if any) for increasing interest rates would be if the drivers of the inflationary pressures were sensitive to that policy change.

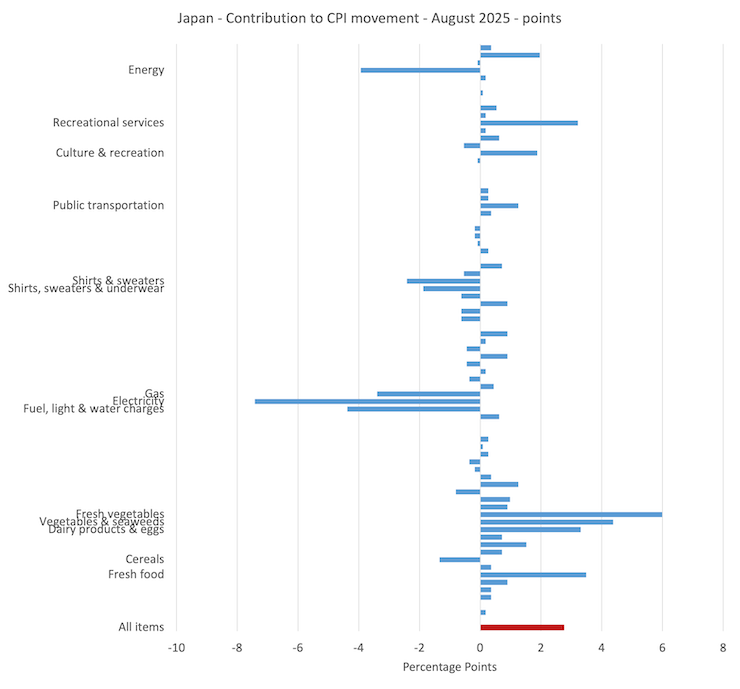

Here is a graph produced from the latest price data issued by the e-Stat service of the Japanese government ((Source).

It shows the contribution to the overall inflation rate of each of the Subgroup indexes for Japan for August 2025.

The All-items index is in red and I have only labelled the larger contributions (positive or negative).

The current inflation is being driven by food prices in Japan.

And the dominant reason for that has been the constrained supply of fresh food as a result of climate-change induced drought and excessive Summer heat.

There is some import price pressure as a result of the depreciated yen.

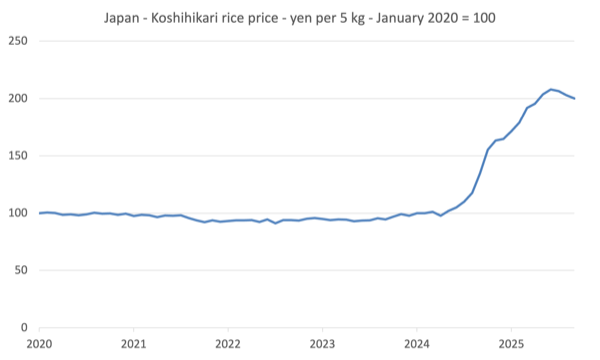

Rice prices, in particular, have risen significantly.

The benchmark – Koshihikari – non-glutinous rice has doubled in price since January 2024.

I found that on my return to Kyoto a couple of weeks ago when I went to my local supermarket and was rather shocked at the price, even though I follow this data all the time.

There is something about the physical reality of the package one is holding and realising that just a while ago it was half the price.

Here is the evolution of that price since January 2020.

It is obvious that this is not purely a pandemic induced problem.

There were three interrelated domestic factors:

1. Drought leading to poor harvest – climate change induced heat wave through the 2023 Summer reduced supply.

2. Farm costs rising – mostly fertiliser and labour costs.

3. Increase in demand as a result of the boom in tourism – particularly Chinese tourists.

4. Large-scale panic buying at supermarkets on the back of a prediction in 2024 that the Nankai Trough was about to deliver the long-awaited earthquake.

But global factors were also at play, including the export restrictions imposed by the Indian government in 2023.

And the climatic factors that impacted in Japan, have been global and have included flooding, excessive heat and lack of rain, which have reduced rice yields.

The important point is that these are all factors, which are largely insensitive to interest rate changes.

So just as it was in the early periods of the pandemic-induced inflation, when the mainstream was calling for rate rises to choke of the ‘excess demand’, we are back in a situation where a largely supply-induced inflation is causing cost-of-living pressure for families.

And, moreoever, the underlying inflation rate, which is computed by taking out the transient volatile factors, is only 1.63 per cent and falling – which some are seeing as a sign that the underlying deflationary culture, particularly the willingness of firms to award higher wages is still low.

The question that mainstream economists have failed to address is whether increasing domestic interest rates will do anything to ease the cost-of-living pressure.

The answer, of course, is that rising rates will exacerbate that situation.

Conclusion

In this regard, Ms Takaichi will push against the Bank of Japan increasing interest rates.

And I think she will be on solid ground.

The other issue that I haven’t addressed here is that by pressuring the Bank, she will further expose the myth of central bank independence.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill I’m having a hard time thinking of examples of Job Guarantee jobs. Maybe something to address. I read this (USA based) paper https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_902.pdf

gives some examples:

Care for the Environment:

“The jobs will tackle: soil erosion, flood control, environmental surveys, species monitoring, park maintenance and renewal, removal of invasive species, sustainable agriculture practices to address the “food desert”2 problems in the United States, support for local fisheries, community supported agriculture (CSA) farms, community and rooftop gardens, tree planting, fire and other disaster prevention measures, weatherization of homes, and composting.”

Care for the Community:

“Jobs can include: cleanup of vacant properties, reclamation of materials, restoration of public spaces, and other small infrastructure investments; establishment of school gardens, urban farms, co-working spaces, solar arrays, tool lending libraries, classes and programs, and community theaters; construction of playgrounds; restoration of historical sites; organization of carpooling programs, as well as recycling, reuse, and water-collection initiatives, food waste programs, and oral histories projects.”

Care for the People:

“The JG aims to support individuals and families, filling the particular need gaps they may be facing. Projects would include: elderly care; afterschool programs; and special programs for children, new mothers, at-risk youth, veterans, former inmates, and people with disabilities. One advantage of the JG is that it also provides job opportunities to the very people benefiting from these programs. In other words, the program gives them agency. For example, the at-risk youth themselves participate in the execution of the afterschool activities that aim to benefit them. The veterans themselves can work for and benefit from different veterans’ outreach programs. Jobs in these projects can include: organizing afterschool activities or adult skill classes in schools or local libraries; facilitating extended-day programs for school children; shadowing teachers, coaches, hospice workers and librarians to learn new skills and assist them in their duties; organizing nutrition surveys in schools; and coordinating health awareness programs for young mothers. Other examples include organizing urban campuses, co-ops, classes and training, and apprenticeships in sustainable agriculture, and all of the above-mentioned community care jobs, which could produce a new generation of urban teachers, artists and artisans, makers, and inventors.”

Dear Kes (at 2025/10/07 at9:07 am)

You might like to read this report that we published in 2008 – https://www.fullemployment.net/publications/reports/2008/CofFEE_JA/CofFEE_JA_final_report_November_2008.pdf

It shows there are hundreds of thousands of suitable jobs.

While it was an application to Australia, the type of jobs are offered in all countries and so the analysis would be relevant across the globe.

best wishes

bill

JG jobs should not replace or serve as a substitute for essential services. If something is essential and is not being provided by the private sector (perhaps it is a public good and its provision is unprofitable) or the public sector, then resources should be diverted away from activities that serve trivial wants, through taxation to free up the required resources and government spending to acquire the freed-up resources and put them to a more appropriate use. Determining what is essential and what is not is a decision that should be made democratically through the ballot box.

The essential services should be incorporated into the conventional public sector (expansion of the public sector share of GDP) and people with the necessary qualifications should be employed at standard award wages. The JG programme should provide useful, but non-essential services (there are plenty of these services currently not being provided, as Bill points out) that can be turned on and off overnight as the pool of JG workers fluctuates.

I find it intriguing that environmental rehabilitation and community services are considered by some JG advocates as ideal for a JG programme, but not medical surgery – as if the ‘environment’ and ‘social health and cohesion’ are non-essential. There are good reasons why an increase in the number of surgeons and medical equipment, if society demands them, should be part of an expanded public sector, with the surgery performed by qualified surgeons. There are equally good reasons why increased public sector employment of qualified ecologists, soil scientists, psychologists, and social workers should accompany an increase in essential environmental and social services, if they are currently deficient.

The JG should not be seen as an expansion of the conventional public sector. It should be designed to employ people looking for paid work, whom, for whatever reason, can’t obtain paid work at their desired number of hours, at a minimum living wage, doing useful but non-essential services. The aim of the JG is to help people through what would normally be a period of unemployment/underemployment whilst they attempt to find work in the private sector or conventional public sector. It would offer educational and training opportunities to assist people back into the conventional labour market.

There will be some people who would permanently remain in the JG pool, for various reasons. Some would consider an entire working-life in JG employment as an undesirable outcome. I would consider it to be a less-than-ideal situation, but one that is a hell of a lot better than the situation these people currently endure, and one which would satisfy one of society’s equity obligations to individual citizens.

What do yo think about dollar-yen rate? It seems that MMT basically does not care about currency rate – weak or strong, but I think the current rate of yen (150-155 yen for 1 dollar) is contributing to the hiked cost of living. Before Abe regime, it was 80 yen for 1 dollar. Raising interest rates would at least increase the value of yen, partly alleviating cost of living?