With an national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

ECB demonstrates that groupspeak is not dead in Europe – the denial continues

On February 10, 2024, a new agreement between the European Council and European Parliament was announced which proposed to reform the fiscal rules structure that has crippled the Member States of the EMU since inception. I wrote in this blog post – Latest European Union rules provide no serious reform or increased capacity to meet the actual challenges ahead (April 10, 2024) – that the changes are minimal and actually will make matters worse. Now the European Central Bank, the supposedly ‘independent’ bank that is meant to be outside the political sphere, has weighed in with its ‘two bob’s worth’ which is ‘sometimes modernised to ‘ten cents worth’) (Source), which would be overstating its value. Nothing much ever changes in the European Union. They have bound themselves up so tightly in their ‘framework’ and rules and jargon that the – Eurosclerosis – of the 1970s and 1980s looks to be a picnic relative to what besets them these days. The latest input from the ECB would be comical if it wasn’t so tragic in the way the policy makers have inflicted hardship on the people (many of them) of Europe.Today’s blog post is Part 1 of a critique of the ECB’s input into the Stability and Growth Pact reform process that is engaging European officials at present. It is really just more of the same.

The concept of Eurosclerosis was all the talk when I was studying in the UK for my PhD in the 1980s.

It was part of the neoliberal assault on workers’ and welfare rights and claimed that Europe’s economic stagnation was the result of excessive government regulation and “overly generous social benefits policies”.

I used to go down to London from Manchester to the LSE where Richard Layard and Stephen Nickell ran their Labour Economics Workshops and listen to their ranting about the need for cuts to welfare etc.

The concept was also used by those seeking to integrate and enlarge the European Union, a move that ultimately lumbered it with the most advanced form of neoliberalism on the planet, the common currency and all of its accompaniments.

Jacques Delors who pushed through the – Single European Act – as EU President in 1986, considered it laying the road for what became the Maastricht Treaty in 1992.

The latest discussions is about reforming the – Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – which define the fiscal rules that have plagued the 20 Member States of the Economic and Monetary Union (the ‘eurozone’).

These discussions signify, even if the parties promoting them do not acknowledge it, that the whole common currency experiment has failed to meet its stated objectives, which is not the same thing as saying it has failed to meet its unstated and probably intended objectives.

The stated objectives were along the lines of convergence of fortunes across the European Continent, higher employment growth, better wages and conditions, better welfare and security for workers and their families, and more.

The performance of the EMU has been abysmal in that respect.

The unstated objectives were to increase the power of the corporate lobbyists and redistribute income to the top-end-of-town.

That has been a success.

The fiscal rules have created the opposite – divergence, erosion of welfare, and a capacity to make economic crises even worse than they would normally be in situations where the fiscal authorities had free rein to use fiscal policy tools to close non-government spending gaps.

In Europe, as a result of the fiscal rules and the application of the Excessive Deficit Procedure – the so-called ‘corrective arm’ of the SGP – nations that endured large non-government spending gaps and rising fiscal deficits as a result of the operation of the automatic stabilisers (tax revenue falling in recession, welfare payments rising), which would normally warrant the discretionary expansion of fiscal policy, were forced, instead, to impose fiscal austerity, which made the already painful economic downturn worse.

In its Occasional Paper Series No 349 report – The path to the reformed EU fiscal framework: a monetary policy perspective – the ECB admit that the:

SGP fell short of the mark in achieving these objectives, at times resulting in a burden for monetary policy. It failed to prevent the emergence of excessive levels of public debt and overly heterogeneous debt ratios across the euro area, and nor did it manage to avoid the tendency of fiscal policies to be pro-cyclical. Moreover, inadequate enforcement of the rules meant that fiscal buffers were not built up in time. Meanwhile, significant cuts in government investment following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and the sovereign debt crisis – which have detrimental longer-term effects – were also a by-product of a fiscal framework that was not designed to protect investment.

They go on to say that the pandemic experience showed that the EU had learned “some lessons” and the “application of pre-reform SGP framework proved to be flexible enough to deal with such exceptionally large shocks”.

Taken together this is an example, par excellence, of why I named my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015).

Taking the last statement first.

The reason the “pre-reform SGP framework proved to be flexible enough” during the pandemic is because the European Commission invoked the escape clause, which effectively abandoned the operation of the fiscal rules.

So it ‘worked’ (sort of – see later) because its ‘teeth’ were taken out.

I guess one could say that was a change of heart for the Commission, which could have adopted the same response to the GFC but chose to enforce the rules, at great damage to the peoples of Europe (well the disadvantaged ones anyway).

The point is that:

1. The Eurozone only survived the GFC because the ECB chose to break the rules within the Treaty pertaining to the no-bailout provisions.

Yes, the ECJ found they didn’t break any rules because they were just conducting ‘monetary operations’ – which involved buying billions of Euro worth of government debt and effectively funding the deficits – sums that represent multiples of what they would need for their liquidity management tasks as the monetary authority.

But they were not content to keep the currency afloat through their various Asset Purchasing Programs that began with the Securities Market Program in May 2010.

They also wanted their pound of flesh via the so-called conditionalities that forced nations to endure austerity in return for the ECB funding their deficits.

Then the ECB partnered with the worst of the worst, the IMF and the Commission to destroy Greece.

The point is that that the survival of the common currency required the central monetary authority to act contrary to the legal architecture of the EMU and would have collapsed if the design of the system was left to dictate the outcomes.

Conclusion: the whole architecture was (and is) dysfunctional and failure prone.

2. The Eurozone survived the first three to four years of the pandemic (sort of) because the Commission decided to relax the fiscal rules and suspend the operation of the Excessive Deficit Procedure.

If the SGP had have been enforced during this time, then several nations, at least would have become insolvent and would have been forced out of the common currency.

Conclusion: the whole architecture was (and is) dysfunctional and failure prone.

The authorities know that, which is why there is all this talk of reforming the fiscal rules.

The only viable reform is to scrap them – and then allow nations to exit the arrangement.

But, the neoliberalism is so embedded in the psyche of the polity in Europe that such a progression will never be countenanced.

Think about the first of those ECB conclusions that justify their support for reforming the fiscal rules.

1. A burden for monetary policy – that is their groupspeak for forcing the ECB to become the default fiscal authority and fund the deficits so that the yield spreads were kept in check.

They were forced into the large scale QE programs because the architecture of the system renders the debt of the Member States subject to ‘credit risk’ (that is, risk of default) and when things turned ugly during the GFC, and the deficits started rising – mostly, in the early period as a result of the automatic stabilisers (such was the severity of the global crisis) – the bond markets demanded higher yields.

Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal – at least would have become insolvent if the ECB hadn’t bailed them out through the QE purchases.

It was the architecture (and the fiscal rules that are part of it) that forced the ECB into this corner.

2. The fiscal rules “failed to prevent the emergence of excessive levels of public debt and overly heterogeneous debt ratios across the euro area” – because the individual Member States should never have gone into the EMU in the first place and the fiscal rules meant that the shock of the GFC would impact differentially across the regional space.

These economies should never have agreed to share a common currency without a federal fiscal authority that issues the currency and can authorise permanent asymmetric currency transfers – which is largely forbidden in the arrangement – being integral to the architecture.

By excluding the federal fiscal capacity, the Maastricht Treaty, set the arrangement up for failure and made it inevitable that the ECB would have to become a default ‘fiscal’ arm of the European economy.

3. “nor did it manage to avoid the tendency of fiscal policies to be pro-cyclical” – the architecture (and the fiscal rules) made it inevitable that fiscal policy would have to be procyclical.

Some explanation: the mainstream claim they hate ‘procyclical’ fiscal intervention.

What does that mean?

It means that when the economic cycle is booming, fiscal policy should not expand spending growth – because then it would be running the risk of pushing the economy over the inflation ceiling.

But think about that for a moment.

If there is a non-government spending gap – which means that total spending is less than is necessary to induce employers to employ all the available labour (and capital equipment etc), then the only solution is for the government to fill that gap with a fiscal deficit.

The fiscal deficit adds to total spending growth and motivates firms to increase output to capture the rising demand, and, in turn, that increases demand for labour.

In that sense, fiscal policy has to be procyclical.

As the economy recovers from the spending gap, then fiscal policy has to ensure spending growth remains within the capacity of the supply-side to respond by increasing production.

But in most situations, fiscal policy has to support growth because the non-government sector typically wants to save some of their income and/or there is an external deficit.

The last thing that a nation needs is for fiscal policy to reinforce the direction of the non-government spending growth in a downturn – which is exactly what the fiscal rules and the enforcement machinery does.

4. “inadequate enforcement of the rules meant that fiscal buffers were not built up in time” – which means the ECB thinks the austerity didn’t go hard enough.

The Commission’s enforcement of the Excessive Deficit Procedure adjustment processes during the GFC was bad enough and prolonged the recession and destroyed the lives of millions of European workers.

Had they required even faster reductions in the deficits, which would have meant even harder austerity, then there would have been a social revolution.

Taken together, one concludes that the authorities in Europe really can’t see past their own blindness.

Conclusion

Nothing much ever changes in the European Union.

In a subsequent post, I will analyse the ECB’s suggestions for the reformation of the SGP and demonstrate how they fail to comprehend why the whole architecture needs to be abandoned.

Advance orders for my new book are now available

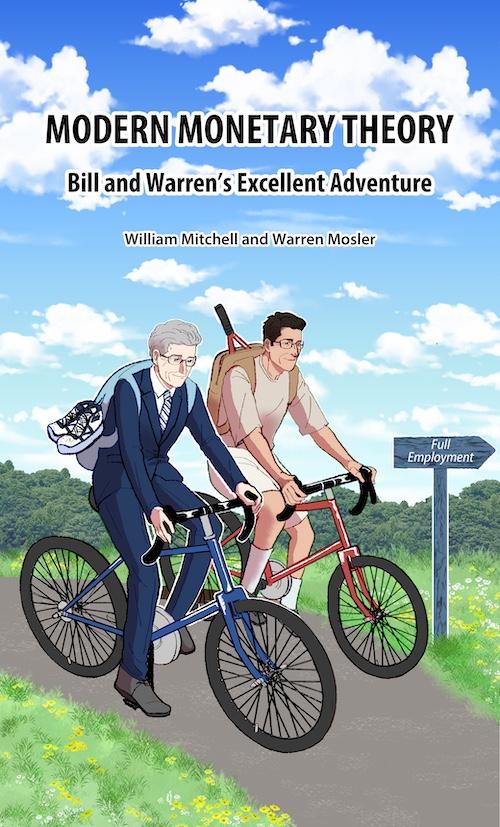

I am in the final stages of completing my new book, which is co-authored by Warren Mosler.

The book will be titled: Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure.

Here is the final cover that was drawn for us by my friend in Tokyo – Mihana – the manga artist who works with me on the – The Smith Family and their Adventures with Money.

The description of the contents is:

In this book, William Mitchell and Warren Mosler, original proponents of what’s come to be known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), discuss their perspectives about how MMT has evolved over the last 30 years,

In a delightful, entertaining, and informative way, Bill and Warren reminisce about how, from vastly different backgrounds, they came together to develop MMT. They consider the history and personalities of the MMT community, including anecdotal discussions of various academics who took up MMT and who have gone off in their own directions that depart from MMT’s core logic.

A very much needed book that provides the reader with a fundamental understanding of the original logic behind ‘The MMT Money Story’ including the role of coercive taxation, the source of unemployment, the source of the price level, and the imperative of the Job Guarantee as the essence of a progressive society – the essence of Bill and Warren’s excellent adventure.

The introduction is written by British academic Phil Armstrong.

You can find more information about the book from the publishers page – HERE.

It will be published on July 15, 2024 but you can pre-order a copy to make sure you are part of the first print run by E-mailing: info@lolabooks.eu

The special pre-order price will be a cheap €14.00 (VAT included).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The latest discussions is about reforming the – Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – which define the fiscal rules that have placed the 20 Member States of the Economic and Monetary Union (the ‘eurozone’).

Did autocorrect replace plagued with placed ?