Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Government debt fears – more fiction from the mainstream media

After all these years of trying, the insights provided by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) still haven’t cut through. One doesn’t even need to accept the complete box of MMT knowledge to know that, at least, some of it must be factual. For example, how much brainpower does a person need to realise that a government that issues its own currency surely doesn’t need to call on the users of that currency in order to spend that currency? Even if we could get that simple truth to be more widely understood it would change things. But every day, economists and the journalists demonstrate a lack of understanding of how the monetary system actually works. Are they stupid? Some. Are they venal? Some. What other reason is there for continuing to use major media platforms to to pump out fiction masquerading as informed economic commentary? And the gullibility and wilful indifference of the readerships just extends the licence of these liars. Some days I think I should just hang out down the beach and forget all of it.

A European friend (thanks RK) who regularly sends me material sent me this transcript yesterday (published May 28, 2024)- How the world got into $315 trillion of debt – which is so misleading that it is dangerous.

This US CNBC program segment was touted as ‘CNBC Explains’ except it didn’t really explain anything.

The pretext for the segment was the latest estimate from the Institute of International Finance that “the world is $315 trillion in debt.”

The IIF is a Washington DC based organisation allied to the financial sector, which provides advocacy and research services to banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, and the like.

One of its stated missions is to:

… promote a better understanding of international financial transactions generally

It appears to raise funds via subscription levies imposed on members and also from corporate sponsorships.

On May 7, 2024, it published its ‘Global Debt Monitor: Navigating the New Normal’, where it revealed that “Global debt rose by some $1.3 trillion to a new record high of $315 trillion in Q1 2024. Moreover, after three consecutive quarters of decline, the global debt-to-GDP resumed its upward trajectory in Q1 2024.”

The Report is for Members Only.

But it motivated the US media company CNBC to produce some headlines and attract some traffic to their news company.

They began their segment by wheeling out a character from the World Economic Forum who told the audience that the global debt level is around that seen during the Napoleonic wars – “close to 100% of Global GDP”.

Then we saw the number $315,000,000,000,000 pop up – all twelve zeros appeared on the screen to convince the viewer that it was a big number.

There seems to be some rules in these sorts of beat ups.

1. Say something over and over using the principle that if you repeat something enough eventually it becomes accepted.

2. Write huge numbers that most people have not clue about other than they look big.

And then the journalist demonstrated that she or her staff could use a pocket calculator with a wide screen and do a division as she offered “Another way to picture” the number with 12 zeros after it:

There are about 8.1 billion of us living in the world today. If we were to divide that debt up by person, each of us would owe about $39,000.

That is another rule:

3. Personalise the big number and induce people to extrapolate their own daily experience to try to understand government financial matters.

Many people owe nothing.

Children owe nothing.

These average figures that the debt phobes love to publish are meaningless in substance and just designed to invoke fear.

Then we get into a bit of detail:

1. “household debt, which includes things like mortgages, credit card and student debt. At the beginning of 2024, this amounted to $59.1 trillion” – so that is, 18.8 per cent of estimated total.

2. “Business debt, which corporations use to finance their operations and growth, sat at $164.5 trillion, with the financial sector alone making up $70.4 trillion of that amount” – 52.2 per cent of the total, of which 22 per cent of the total is in the form of ‘gambling’ debts held by speculators.

3. “Public debt stood at $91.4 trillion” – 29 per cent of the estimated total.

The CNBC segment wants us to believe that there is a major problem here.

But there are major problems with that inference.

First, adding the government debt to the non-government debt is invalid.

The non-government debt is held by currency users who face a financial constraint and any debt that they incur carries a credit risk – that is, a risk of default.

In most cases, government debt is credit risk free because the issuer is the also the currency issuer and can always meet outstanding liabilities denominated in that currency.

There are exceptions which I note below.

The real problem is the private debt although that conclusion also needs to be qualified.

For many households, the majority of their commitment is in the form of mortgage debt, and most people are able to meet the obligations and succeed in owning their own home, where that culture exists.

In Australia, around 37 per cent of houses are subject to mortgages.

The problem comes when families are pushed into large loans by banks etc, which rely on both adults (for example) working to meet the payments.

Often the second breadwinner combines casual work with home responsibilities and in a downturn they are the first to lose working hours as firms start adjusting to falling sales growth or even contraction.

That sort of debt is precarious and the consequences for the debt holder concerned can be devastating if they fail to meet the obligations.

The corporate debt which is used for investment purposes and working capital is also usually not an issue if the decision making is prudent.

Obviously, when bubbles start to occur and the borrowing frenzy is full-on, the prudential oversight declines and excessive and precarious debt obligations are taken on.

The unfolding insolvencies can spread via the expenditure multiplier and create a major disaster – cue the GFC.

But as I wrote during the GFC – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still! (October 11, 2010).

The statement – “There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending” – was the title of a paper I published in 2008 – you can read the – Working Paper – version for free (fairly close to the final publication).

It reflects a basic insight that is derived from MMT once you fully understand that school of thought – its scope and its limitations.

Through sensible fiscal action, a situation can always be improved from where it is as a result of a crisis in the private financial markets.

Second, adding all public debt to get a grand total is invalid.

The debt issued by the Australian government is credit risk free.

The debt issued by any one of the 20 Member States of the Eurozone is not credit risk free because those governments use what is effectively a foreign currency.

If such a government wants to spend more than their tax revenue then they must gain the extra euros from the private bond markets, which may then demand higher yields as the risk increases.

In the situation where a Eurozone Member State is enduring mass unemployment and declining tax revenue, the situation becomes complex.

While there are no real resource constraints in this situation, the financial constraints persist.

As the automatic stabilisers increase the fiscal deficit (lower activity reduces tax revenue and increases welfare spending automatically), the nation must increasingly access funds from private investors.

Given the credit risk attached to such debt, the bond markets will require higher yields on newly issued debt as the governments capacity to raise taxes to repay the outstanding debt obligations becomes impaired when there is high unemployment.

And, perversely, the higher the yields the lower the ability to repay and the higher the default risk, as it soon spirals into default with no funding at any price.

So even though there is mass unemployment and chaos, the bond markets might refuse to fund such a government at sustainable yields because of fear of debt default.

This is the situation that occurred in 2010 and 2012 in the Eurozone crisis as yields skyrocketed on the debt of various nations (for example, Italy and Greece).

It was only the intervention of the ECB (the currency issuer) guaranteeing that all national government debts would be repaid at maturity that saved all of the Euro nations from insolvency.

Most governments that issue their own currency can never get into this type of dilemma.

Which means the $91.4 trillion debt estimate is meaningless.

Third, adding all public debt from all currency denominations is invalid.

Most governments borrow only in their own currency, which means they can never encounter a situation where they cannot meet the outstanding liabilities when they come due.

How much of the $91.4 trillion is covered by this class of government is not known to me today but it would be a significant proportion (well over the majority).

Which means the $91.4 trillion debt estimate is meaningless.

So that leaves the $315,000,000,000,000 figure looking rather wan, doesn’t it?

The journalist also tells her audience:

Finally, there’s government debt, which is used to help fund public services and projects without raising taxes.

Countries can borrow from each other or from global institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

But governments can also raise money by selling bonds … which is essentially an IOU from the state to investors. And like all loans, it includes interest.

So all you MMTers now know how to respond to that garbage.

Government debt doesn’t fund anything.

It is just an unnecessary operational convention that is a hangover from the fixed exchange rate era.

Moreover, the continuing issuance of public debt for most governments (those that issue their own currencies) is in one sense political – in that it allows the conservatives to scream about the burdens on their grand kids, which is a short hand way of constraining government spending on welfare other than that that accrues in the form of corporate welfare – and in another sense, it provides the kids in the financial markets with a play thing to pursue their speculative greed – corporate welfare again.

We have a chapter in our new book (see below) entitled – ‘MMT Barbarians Enter the Gates of Canberra’ – where we discuss that topic.

The journalist also characterises government “debt … [that has] … been piling up” as the result of government spending “beyond their means” – the classic ‘spending like a drunken sailor’ type metaphor designed to invoke our disdain for wasteful profligate governments.

The means available to government have nothing to do with finances.

The IMF and all those bodies like to define ‘fiscal space’ and ‘fiscal sustainability’ in terms of debt to GDP ratios, or deficit to GDP ratios.

For most governments those indicators are meaningless and have nothing to do with the available fiscal space, which can only be meaningfully defined in terms of available real productive resources that can be brought into productive use through expenditure.

Those are the ‘means’ that a government has to play with as it seeks to provision itself in order to meet is electoral promises.

So if there is full employment (of all resources) and the government keeps ramping up nominal spending growth then it will impart inflationary pressures and at that point we can say it is ‘living beyond its means’.

But that has nothing to do with the size of the fiscal balance or how much outstanding public debt there is.

The CNBC segment also asks the related question: “how much debt is too much debt? When does it become unsustainable?”.

Her answer:

Put simply, it’s when you can no longer afford it.

So, for example, when a government is forced to make cuts in areas that hurt its people, such as education or healthcare, just to keep up with payments.

As long as there are real resources available the currency-issuing government ‘can afford’ to keep spending in order to bring them back into productive use.

There is never a justification for cutting spending when there is excess capacity in the economy. NEVER.

Some relevant extra reading:

1. Anything we can actually do, we can afford (February 15, 2024).

2. Look after the unemployment, and the budget will look after itself (March 5, 2012).

The titles of those blog posts came from John Maynard Keynes of course.

In the middle of the Second World War, British economist John Maynard Keynes made a series of radio speeches on the BBC about post War planning. As an allied victory was becoming more likely, Keynes outlined a substantial investment program for the British government to upgrade its housing stock, build educational and performing arts capacity and other infrastructure.

His ideas received significant push back from the elites in the financial and economics establishment who claimed that Britain would not have enough financial capacity to achieve his aims.

On April 2, 1942, the topic he addressed was ‘How Much Does Finance Matter?’.

The speech went like this (Keynes, 1978: 264-265):

For some weeks at this hour you have enjoyed the day-dreams of planning. But what about the nightmare of finance? I am sure there have been many listeners who have been muttering:

‘That’s all very well, but how is it to be paid for?’

Let me begin by telling you how I tried to answer an eminent architect who pushed on one side all the grandiose plans to rebuild London with the phrase: ‘Where’s the money to come from?’ ‘The money?’ I said. ‘But surely, Sir John, you don’t build houses with money? Do you mean that there won’t be enough bricks and mortar and steel and cement?’ ‘Oh no’, he replied, ‘of course there will be plenty of all that’. ‘Do you mean’, I went on, ‘that there won’t be enough labour? For what will the builders be doing if they are not building houses?’ ‘Oh no, that’s all right’, he agreed. ‘Then there is only one conclusion. You must be meaning, Sir John, that there won’t be enough architects’. But there I was trespassing on the boundaries of politeness. So I hurried to add: ‘Well, if there are bricks and mortar and steel and concrete and labour and architects, why not assemble all this good material into houses?’ But he was, I fear, quite unconvinced. ‘What I want to know’, he repeated, ‘is where the money is coming from’.

Keynes continued to articulate what he considered to be the mistake in the reasoning confronting him and then said (Keynes, 1978: 270):

Where we are using up resources, do not let us submit to the vile doctrine of the nineteenth century that every enterprise must justify itself in pounds, shillings and pence of cash income, with no other denominator of values but this. I should like to see that war memorials of this tragic struggle take the shape of an enrichment of the civic life of every great centre of population.

Why should we not set aside, let us say, £50 millions a year for the next twenty years to add in every substantial city of the realm the dignity of an ancient university or a European capital to our local schools and their surroundings, to our local government and its offices, and above all perhaps, to provide a local centre of refreshment and entertainment with an ample theatre, a concert hall, a dance hall, a gallery, a British restaurant, canteens, cafes and so forth.

Assuredly we can afford this and much more. Anything we can actually do we can afford. Once done, it is there. Nothing can take it from us. We are immeasurably richer than our predecessors. Is it not evident that some sophistry, some fallacy, governs our collective action if we are forced to be so much meaner than they in the embellishments of life?

Yet these must be only the trimmings on the more solid, urgent and necessary outgoings on housing the people, on reconstructing industry and transport and on replanning the environment of our daily life. Not only shall we come to possess these excellent things. With a big programme carried out at a regulated pace we can hope to keep employment good for many years to come. We shall, in fact, have built our New Jerusalem out of the labour which in our former vain folly we were keeping unused and unhappy in enforced idleness.

So when someone says to you “How are we going to pay for it?” you can simply reply as Keynes did ‘Anything we can actually do we can afford’.

The ‘How to pay for it’ question arises out of ignorance concerning the way government spending enters the economy.

The sequence is as follows:

- The parliamentary system authorises government to make the relevant payments.

- The Treasury or Finance department instructs the nation’s central bank to credit (change to a higher number) the recipient’s bank account balance (called a reserve account) at the central bank.

- The bank of the recipient then records a deposit in the account of the supplier of the goods and services to the government.

That’s it.

There are no taxpayers or grand kids are in sight!

The final point to consider is the absurdity of the notion that under current institutional arrangements, where governments match their fiscal deficits with debt issuance, that both the non-government and government sectors can reduce their overall debt levels simultaneously.

If you are perplexed by that statement then read this blog post – Not everybody can de-lever at the same time (May 23, 2012).

That discussed the situation during the GFC when everyone was talking about government debt being too high and that the combination of high levels (whatever that is) of public debt and private debt were a dangerous cocktail.

There were calls for policies to reduce government debt while also reducing non-government debt, which had become excessive and driven the financial crisis.

The simple fact is that when private spending is subdued the government sector has to run commensurate deficits to support the process of private de-leveraging by sustaining growth.

Those advocating fiscal austerity or those who claim that the amount of outstanding private debt is simply too large for the Government to replace with public debt fail to understand the basic tyranny of the sectoral balance arithmetic.

Put simply, not everybody can de-lever at the same time.

Even progressives like Steve Keen got caught up in this flawed and inconsistent way of thinking.

Conclusion

That’s it.

Pretty depressing.

I am now going back to the final edits for our new book which will be available for delivery on July 15, but you can become part of the first print run by following details below.

Warren and I think readers will like what we have come up with.

Advance orders for my new book are now available

The manuscript for my new book, co-authored by Warren Mosler, goes to the publisher tomorrow.

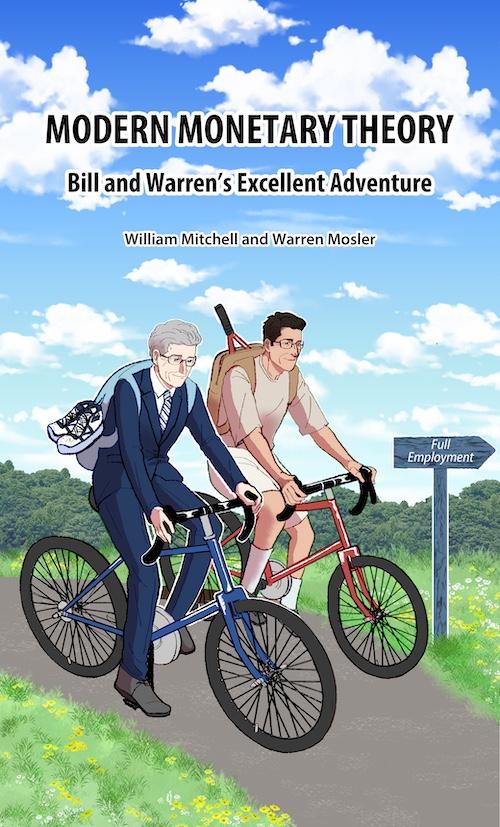

The book will be titled: Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure.

Here is the final cover that was drawn for us by my friend in Tokyo – Mihana – the manga artist who works with me on the – The Smith Family and their Adventures with Money.

The description of the contents is:

In this book, William Mitchell and Warren Mosler, original proponents of what’s come to be known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), discuss their perspectives about how MMT has evolved over the last 30 years,

In a delightful, entertaining, and informative way, Bill and Warren reminisce about how, from vastly different backgrounds, they came together to develop MMT. They consider the history and personalities of the MMT community, including anecdotal discussions of various academics who took up MMT and who have gone off in their own directions that depart from MMT’s core logic.

A very much needed book that provides the reader with a fundamental understanding of the original logic behind ‘The MMT Money Story’ including the role of coercive taxation, the source of unemployment, the source of the price level, and the imperative of the Job Guarantee as the essence of a progressive society – the essence of Bill and Warren’s excellent adventure.

The introduction is written by British academic Phil Armstrong.

You can find more information about the book from the publishers page – HERE.

It will be published on July 15, 2024 but you can pre-order a copy to make sure you are part of the first print run by E-mailing: info@lolabooks.eu

The special pre-order price will be a cheap €14.00 (VAT included).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Our professor has put considerable time and effort into Australia’s Alan Kohler by explaining the ins and outs of fiat money creation/MMT to him. Kohler claims to understand but has an inordinate fear that politicians who know the actualities will want to spend without limit so is of the school that the money creation lies must be maintained because knowledgeable politicians can’t be trusted with the truth. Well, guess what, politicians can’t be trusted either way as they will say one thing and do another because that is essential to their stock in trade. So long as we pay attention to what politicians say and not what they do, they will continue to con the voters.

Anyway, as recently as 27 May, Alan Kohler produced an opinion piece for The New Daily entitled “Market failures and ….made in Australia” where he comes across as if he’s never heard of MMT or fiat money creation. All in keeping with his fear of politicians knowing the truth?

To demonstrate Kohler’s failure to (want to) accept/appreciate the realities of public money creation he writes “We simply don’t have enough money” and “It’s an expensive idea and can’t last – the government simply hasn’t got enough money to follow through and go all the way.” when what he should be saying, based upon what he (says he) knows, is that money availability isn’t the issue because……, but that a lack of political will to act to employ the relevant resources for the public good is all that is holding the public spending back. Politicians (or, rather, their puppet masters) running the show just don’t want to do that!

Kohler appears to have fully returned down the rabbit hole of the orthodoxy as if he’d never heard of MMT. He mentions that “Ross Garnaut points out, a tax on fossil fuels would raise billions of dollars and not only pay for the energy transition but also help pay for the NDIS and the other growing demands on government spending.” Out of his own mouth Kohler squarely places himself in the “taxes to pay for” camp.

All that wasted effort from Bill explaining the irrefutable logic of the answer to “how much brainpower does a person need to realise that a government that issues its own currency surely doesn’t need to call on the users of that currency in order to spend that currency?” to end up with another supporter of the ignorant orthodoxy. So sad. Shame on Alan Kohler.

The presenter on BBC’s Breakfast show this morning invited viewers to compare government spending with their household budgets when considering their taxation pledges. I would complain again but I it didn’t work last time.

How can we persuade the BBC to acknowledge the purely ideological basis of the Labour & Tory “funding” promises?

They did post https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-50579897 following an earlier complaint of mine but that’s the only time I’ve seen MMT discussed by them.

As I understand it government debt is some ones savings so that to reduce government debt means private savings must be reduced. The rich who own most of the debt will not be happy about that.

That’s what I was thinking, Ben. I’m old enough to recall some nervousness on Wall Street when Clinton was running his surpluses — among other things, without risk-free-rate instruments provided by government, how could other debt products be properly priced?

“among other things, without risk-free-rate instruments provided by government, how could other debt products be properly priced?”

Simple. You price off zero, the natural rate, since that would be the marginal cost of the liabilities.

Loans are just a mark up on the cost of stopping liabilities heading elsewhere, with the ultimate elsewhere being the deposit facility at the central bank which pays an artificial administered rate to one side and charges an artificial administered rate on the other.

The outcome of the debt fairytale is that the global south is so much stranded into debt, that many countries, now, work only to pay interest to banks.

No money left for anything else.

That’s the reason behind the migration crisis in Europe and in north America.

That’s the reason why there’s a Gigantic humanitarian crisis in Africa RIGHT NOW.

Many of you might never heard about it.

The media outlets were busy talking about the houthis’ bullet holes in some ships in the red sea, but don’t care a dime for those dying of hunger and disease in Afghanistan, Syria, Myanmar, Central America, Haiti, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Northern Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritreia, Somalia and Yemen.

The global north is a failure.

But, You should have no ilusions: it won’t stop.

They’ll keep at it, as long as we keep electing their vassals, either right or left.

The ponzi scheme is going all the way up until the planet busts into the nuclear armageddon.

Currency sovereign governments do not spend in their own currency; they invest by creating streams of money and directing their flow. Nor do such governments incur debt in their own currency; they only obligate themselves to create particular streams of money and direct them in certain directions. So long as MMT continues to use loaded, outmoded language like government spending and government debt when talking about currency sovereign governments, it will continue to waste precious time and energy in the perhaps futile effort to redefine such misleading terms, so laden with negative connotation in the macroeconomically-confused public mind.

@ Fred Schilling:

Yes, Kohler is a good example of why MMT has failed to make it to the mainstream ; he said in a New Daily article recently “no-one is talking about MMT now (compared with 2 years ago), but everyone is doing it, evidenced by acceptance of deficit spending”.

Well, no-one is doing a Job Guarantee, and Chalmers is still bleating about being “constrained by the Liberal debt”; Kohler is complicit is all the mainstream lies.

Even more disturbing, an MMT educator claims Kohler is correct when he said (in the same article) “MMT doesn’t give the government permission to fund itself”. Hopeless; we NEED the currency-issuing government to fund itself. Ross Gittins is another loss; Ross originally agreed (in an article : “fiunding the budget by printing money is close than you think”) that requiring the government to sell bonds to fund spending is mere convention, but 6 months later he withdrew “after a conversation with a fossilized central banker” (in an ardtle: “there’s no such thing as a free lunch after all”) who said there is always a debt associated with spending….. surely micro double-entry bookkeeping gone mad in the macro economy, apart from the misleading mainstream idea of a “free lunch”

I recall even Bill (even if correctly) objected to Gittins’ use of the words “printing money”, no doubt because of the association with hyperinflation; but all MMTers know “money printing” merely refers to changing the digits in bank computers.

Sad.

On the 14th of February, 1966 Australia changed from Pounds, Shillings and Pence, to Decimal Currency.

It’s a date embedded in my memory of primary school. The big day was preceded by a thorough education process for school students, with special periods set aside to learn about the new system and a lot of written material featuring the aptly named “Dollar Bill”.

I suppose that my parents and adults across the country received versions of the same information in the post, because everyone seemed to manage the transition successfully.

No such consideration seems to have been afforded to the people of Australia when we moved to a fiat currency – certainly I have no memory of any effort to educate the population to the ramifications of such a significant change. I remained ignorant like most Australians until I chanced to hear about MMT many years later.

A simple education program that explained the indisputable facts distinguishing the new system from the former fixed currency might have given serious jounalists and other interested people the confidence to challenge the confusing muddle of misinformation that has since surrounded the economic role of the Federal Government.

It may have enabled more inquisitive minds over the ensuing years to distinguish fact from fiction and to discover that there is an alternative to the the mainstream theory supporting neo-liberalism.

Newton Finn’s comment, above, is spot on.

Ultimately, the distinction between a stock and a flow is arbitrary. No wonder there is confusion in the public mind.

Money is understood by the public as a store of value—a stock. MMT sees money as a medium of exchange—a flow.

But as the long history of the stock and flow debate in economics illustrates, the difference between stocks and flows is nowhere near as transparent, on close examination, as one might suppose.

Hello Bill;

I feel the same way!

However, I see it as a Political Problem, which requires a Politically viable policy Solution, rather than expecting the people to understand common sense MMT.

And that would be to stand for a policy where a State like South Australia or Victoria would impement a 2nd currency designed a bit like the Buckarro. Crucially, it would be a 2nd fiat currency so Voters are not afraid of it failing. It could also be an opt-out solution to make it more popular.

And those who take part in it would elect the Board that makes choices about the currency, and even possibly how it is spent.

“As long as there are real resources available the currency-issuing government ‘can afford’ to keep spending in order to bring them back into productive use.”

Doesn’t one have to show that there are real resources available for the government to do what it wants to do? If not, then doesn’t one have to show how the government is going to get those resources? And doesn’t this assume that the government has a whole-of-economy view?

That is,

How does a government know that there are or are not real resource constraints?

Sergio, in the short term, the best way to tell if there are resource constraints is price signals.

“But he was, I fear, quite unconvinced. ‘What I want to know’, he repeated, ‘is where the money is coming from’.”

FROM THE PRINTING PRESS YOU MORON!

I know Bill has objected to the printing press trope, but it resonates with lay people, and printed money and electronic money have exactly the same economic effects. We only tend to favor electronic money because it is more convenient and secure. Not to mention more sanitary.

“but it resonates with lay people, and printed money and electronic money have exactly the same economic effects”

Yes, but it leaves people still with the idea that money is some thing which has to come from some where before anybody can spend it. True for them and you and me, but for a sovereign state money is FIAT. It is a pure product of will and imagination. And that’s why it’s bullshit for a sovereign state to say “Aw, gee. We want to, and we’d rilly, rilly love to but we Don’t Have The Money.” As they keep doing.

Ha! The UK Guardian has called out the BBC on their reporting and attempted an explanation on government debt….

Don’t hold your breath!

https://www.theguardian.com/business/article/2024/jun/13/why-government-debt-is-not-like-household-borrowing

MMT needs a political “champion”. To progress anything in a political environment needs a champion who can advocate the cause. There are influential people outside the party political system who need to be brought on board with MMT like Simon Holmes À Court and his band of moderate cross-bench Teals including in particular Allegra Spender and Monique Ryan. These are highly intelligent people and Spender is especially interested in tax reform. Having someone in parliament as an advocate and can push the MMT agenda amongst largely brain dead politicians would be a big step forward.

It would be much more persuasive and politically attractive if the $1T of (Australian) government debt was referred to as $1T of ‘private sector wealth’. So why are we referring to the other side of the ‘debt ledger’ as ‘savings’? People think about ‘savings’ as what’s in their bank account and people with a mortgage don’t have ‘savings’ so it’s irrelevant to them.

@ Philip Orr:

I asked Green’s Senator Barbara Pocock, a former Central Bank employee no less, to promote MMT in Parliamert; she said “now is not the right time because of inflation” ….

Hopeless…..

Note: Inflation is THE single issue why mainsteam economistrs (and politicians following their flat-earth economics) reject MMT; and imo, MMT educators are somewhat vague wih their taxes and a Job Guarentee as the chief inflation cotrol methods. And then there’s prof Phi;ip Lawn recommending a carbpn tax to hasten transition to a green economy , despte the fact the electorate reject carbon taxes.