These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

A very dangerous variant of the global virus is spreading again after being subdued throughout 2020

There is a new variant of the global virus spreading again after being subdued throughout 2020. This is a very dangerous variant and if it takes hold will guarantee massive human suffering, and, a further, substantial shift in national income towards the top-end-of-town. I refer to the creeping infestation that is starting to pop up claiming that austerity will be required to pay for all the “profligacy” associated with government approach to the pandemic. I have seen this virus in the wild and it is creepy and being spread by those who seem to want to gain attention as time passes them by. Overheating threats, austerity threats – it is all part of the economics establishment trying to remain relevant. A vaccine will not work. They need to be permanently isolated.

In Britain, the austerity mavens are creeping out of the woodwork.

The Prospect Magazine article (January, 26, 2021) – In defence of austerity – written by a “former head of Treasury”

The sub-title begins the twisted framing: “Free money is in vogue-but there’s no such thing” – the only cost of the Bank of England buying all the debt being issued by H.M. Treasury is the wear and tear on the computer keyboards that type in the numbers.

The pandemic has exposed to an increasing number of people that there is ‘free money’. They are realising that numbers just appear in bank accounts.

Perhaps this former official should watch the recent speech and subsequent Q&A from the Reserve Bank of Australia governor, Philip Lowe to the National Press Club in Canberra (February 3, 2020).

– Speech.

He was asked by a journalist in the Q&A:

Could you please explain in the simplest terms, perhaps keeping in mind your audience outside of this room, when the RBA decides to purchase government bonds, as it’s doing, where does the RBA get that money from? Is it simply a matter of printing new money? How does it work?

The Governor replied:

Well, it’s not printing money. People think of it as printing money, because once upon a time if the central bank bought an asset, it might pay for that asset by giving you notes, you know, bank notes. I’d have to run my printing presses to do it. We don’t operate that way anymore, obviously because we live in an electronic world. When we buy a bond from a bank, the way we pay for that is credit. The banks, we’ll use Westpac, who’s the sponsor of today’s event as an example. If we bought a bond from Westpac, we would credit Westpac’s account at the Reserve Bank, and that creates the money electronically. That’s how a modern system works. And then Westpac could use that money hopefully to make some loans to some of its customers. But we can create money electronically, and that’s what we do these days …

The Central Bank is the only one who can do that. That’s the unique feature of a central bank …

Free money folks!

As an aside or diversion to today’s blog post, the Governor was also put on the spot about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

A journalist asked him:

Governor, I thought I better throw in about the old Modern Monetary Theory debate, because it rages on. We’ve got this huge amount at the moment, obviously, of bonds being bought last time around during the GFC, perhaps the inflation a lot of people predicted didn’t come, but if it does at some point, obviously a massive or a spike in inflation is a pretty bad thing for an economy. Are you looking at any other warning signs aside from just inflation itself as to whether that’s a threat in the future, given all the government bond buying at the moment?

The Governor in denial (unconvincing) mode replied:

Well, just for clarity, we’re not involved in Modern Monetary Theory, which is the central bank directly financing the government. We don’t do that. We will not do that, it’s not on my radar screen. So you may have heard me before say Modern Monetary Theory – there’s not much monetary, not much modern, not much theory in it. But the more substantive part of your question was is there inflation risk? That’s more serious than the one I’ve been articulating. It’s possible. I think it’s very unlikely again, because to have sustained increases in inflation, we’ve got to have sustained increases in wages. And for the reasons I was talking about before, I just don’t see that on the horizon.

First, his characterisation of MMT reveals his desire to shut down the debate by using a simplistic characterisation of our work. I won’t deal with that here.

Second, it is true that the central banks who are buying up massive quantities of government debt are not “directly financing the government” (left pocket-right pocket stuff) because the bond auction charade is on-going.

Debt is issued in the primary market and the dealers know they have a high probability of off-loading it to the respective central bank via secondary bond market purchases.

So we are just playing with words.

The reality is that the central banks (left pocket) is putting currency into the treasury (right pocket) accounts, which the accounting conventions then allow the treasury to spend.

This is the mainstream taboo.

Third, mainstream theory predicted that as a result of central banks breaking the taboo not to purchase government debt that inflation would accelerate.

So the better question to the Governor is why hasn’t inflation accelerated in the face of the expansion of central bank balance sheets (buying government debt)?

Anyway, back to the former H.M. Treasury official, one – Nick Macpherson – claiming austerity is inevitable for Britain.

The article rehearses all the narratives.

He acknowledges that there is record peacetime debt “set to rise” and the government is issuing 10-year bonds at near zero interest rates and no impacts on the exchange rate.

And “the markets haven’t batted an eyelid.”

And why would they? The level of corporate welfare is also at peacetime records.

So as more people realise that the rising debt is not going to result in disaster – a realisation that Mr Macpherson (the Eton-Oxford education Baron of Earl’s Court) – calls “A cosy consensus has emerged across left and right” – it is getting harder to rehearse the debt phobia narratives.

The ‘Baron’ recognises the empirical world is not supportive of the debt phobia narratives (Japan, low yields everywhere, etc) but hangs onto it anyway.

He invokes the ill-fated decision by Britain to enter the “Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1989” only to leave in 1992 as a reason that the “case for fiscal rectitude remains as strong as ever.”

I laughed when I read that.

The British government had initially refused to join the EMS but was clearly divided between the pro-European camp and the Thatcher camp.

The latter correctly saw that membership of the EMU would compromise Britain’s policy sovereignty.

However, with Thatcher’s star on the wane and the elevation of the pro-European John Major to the role of Chancellor to replace Nigel Lawson, the Tories turned towards joining the ERM.

The decision confronted British jingoism (Thatcher’s anti-German sentiment) with the ahistorical ideology of Monetarism, which were both in play during the Thatcher years.

Drawing on the Monetarist influence, Major and Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd argued that Britain could expunge the high inflation left over from the oil price shocks if it tied the pound to the German mark, which was equivalent to saying that the Bank of England would passively follow Bundesbank interest rate policy.

At the time the Bundesbank was pushing interest rates up beyond the level that would be considered appropriate for a recessed British economy.

Major and Hurd won over Thatcher and Britain joined the ERM on October 8, 1990, while mired in a deep recession with an overvalued currency (2.95 marks per pound).

Once Major took over as Prime Minister in November 1990, following Thatcher’s demise in the same month, the British Government touted Britain’s membership of the ERM and the so-called ‘inflation anchor’ as the a central aspect of Britain’s anti-inflation policy.

It was a very misguided decision.

In the late 1980s, governments were abandoning capital controls, which had previously been the reason currencies were relatively stable in Europe, because of the introduction of the Single European Act 1986 which stipulated that all capital control had to be abolished by July 1, 1990.

The capital controls had protected central banks from speculative attacks on their foreign exchange reserves and allowed nations to focus more effectively on domestic policy targets (economic growth and low unemployment).

Once the controls were eliminated, were eliminated, central banks became vulnerable, as they had to focus policy on defending the nominal exchange rate parities.

By 1992, this vulnerability became acute.

The referendum failure in Denmark on June 2, 1992 brought some reality back into European financial markets by pricking the false bubble of currency stability.

It was obvious that Italian and British competitiveness had been severely eroded by their higher inflation rates and that their currencies were substantially overvalued, particularly against the mark.

The politicians pushing for the EMU saw the dark clouds emerging in the international currency markets as a sign that they had to move more quickly to introduce the single currency and impose harsher fiscal rules on Member States.

The Bundesbank didn’t help matters when it pushed up interest rates on July 16, 1992 because of its concern for rising inflation associated with the reunification.

The increased German interest rates forced Germany’s neighbours to increase their own interest rates beyond the levels deemed prudent given their domestic circumstances.

Monetary policy was locked into ensuring the exchange rates were stable and higher unemployment was the casualty.

The increasing political backlash to the high unemployment raised further doubts in the financial markets as to the commitment by policy makers to maintaining the ‘no realignment’ policy.

The EMS was now on very shaky ground.

And with Italy going into currency crisis and resisting devaluation, their interest rates skyrocketed.

France was also in crisis as it approached the ratification referendum on September 20 (especially after the Danish result).

And in Britain was enduring high unemployment and didn’t want to devalue (national pride type justifications).

It demanded Germany reduce interest rates to ease the speculative pressure on the exchange rate but the Germans refused, pushing the instability on Italy and Britain.

The obvious happened and while tying the pound to the mark lowered inflation, it was at the expense of a deepening recession and worsening unemployment.

By the ‘Summer of ’92’, the pressure on the pound was unbearable.

And then Wednesday, September 16, 1992 dawned, and the ‘skies became darker’ as the day progressed.

As the day unfolded it became obvious that Britain could not tie its currency to the mark and expect to avoid speculative attacks.

Black Wednesday was inevitable for Britain because the Government had been blinded by Monetarist ideology and failed to appreciate what ERM membership meant for domestic policy – sustained high unemployment and on-going austerity.

The decision to enter the ERM was driven, in part, by John Major’s delusion that the sterling would replace the German mark as the region’s anchor currency.

The episode tells us nothing about the need for on-going “fiscal rectitude”.

It only told us that a nation that surrenders its currency sovereignty to join a currency arrangement where a strong industrial exporting economy dominates (Germany) then it has to expect to maintain austerity indefinitely if it wants to keep its currency within the agreed fixed bounds.

But the real lesson was the madness in joining such arrangements.

The 19 Member States of the Eurozone live that madness on a daily basis.

Britain went free on Black Wednesday, 1992.

So that little historical reference doesn’t help his case at all.

The question that the sound finance types refused (and refuse) to ask is why would Britain want to fix its currency. That was the issue.

At least Margaret Thatcher understood that it was not wise to have anything to do with the ERM, especially with Germany as the dominant nation and with the Bundesbank demonstrating a consistent history of refusing to behave according to the rules set, which required symmetric foreign exchange market intervention.

Mr Macpherson then tries another tack – the inflation and market pressure tack.

It always descends into this.

So he knows “the Bank of England can buy Britain’s debt.”

But it won’t do that “indefinitely” because it “took many years to win its independence”. The ‘win’ was not an operational shift just a piece of political window dressing that legislative change could alter any time the Government chooses.

But why would the Bank suddenly stop buying government debt?

Well apparently because “concerns about inflation are likely to revive”.

Which are?

The purchase of the debt does not alter the inflation risk built into the spending that the debt issuance matched (note: did not fund).

The Bank of England could just type zero against its British government debt holdings and nothing material would happen.

The inflation risk was in the spending and that has flowed into the economy and is doing its thing. And I haven’t seen any signs of inflation or inflationary expectations as a result.

He also claims that the UK is different to Japan, which by implication means he is conceding that there should be no concerns about Japan’s deficits and debt situation.

The difference, apparently is that:

… the UK doesn’t have an effective “captive market” of savers. The British people, and the governments they elect, have always favoured consumption over investment. That means the UK has to rely on the kindness of strangers, as former governor Mark Carney once put it, to finance deficits. Foreign investors own a little under 30 per cent of Britain’s debt. Lose their confidence and we have a problem.

Kindness is not involved. Bond markets are not about kindness or generosity.

It is true that the Overseas Holdings of Central Government liabilities amount to 27 per cent of total as at the September-quarter 2020.

You can find all the data on British government debt from the UK Debt Management Office – Gilt Market Page.

The Bank of England’s share is now 30 per cent and rising.

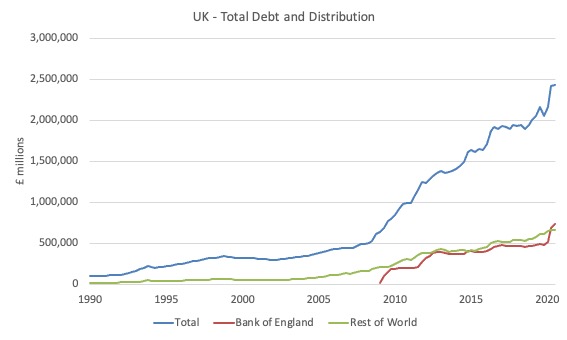

The following graph is very interesting.

It shows total Central Government liabilities and the debt held by Overseas Holdings and the Bank of England.

The rising purchases by the Bank of England since the GFC have tracked the Overseas Holdings.

You could construct this as saying that the British government is not exposed at all to foreign purchases of its debt.

But that would be falling into the trap that their purchases mattered in the first place.

Remember, the DMO auctions the gilts and the auction clears every time because the bid-to-cover ratios are typically high.

So if the foreigners withdrew from the auction perhaps the yields would rise a little until the Bank of England used its currency capacity to suppress them again.

It is a nonsense to think that British government spending is at the best of these ‘kind’ strangers.

If they “lose their confidence”, then the UK doesn’t have a problem, they do. They lose their dollop of corporate welfare and the British government doesn’t blink an eye.

Which then makes the next historical reference by Macpherson rather ludicrous.

One might easily just say – Not this again?

He writes:

The UK crises of 1976 and 1992, and the global one in 2008, involved a slow build-up of risk, followed by an inflection point as investors lost confidence and the dam burst. The government should be careful.

What?

1992 – see above – situation is not applicable to Britain’s floating currency.

1976 – The government lied to the people that it needed to borrow currency from the IMF. It just want to shift the blame for their growing interest in austerity as Dennis Healey became infested with Monetarism onto an external force so they could keep sweet with the unions under the social contract in place at the time.

Here are some analyses of that period:

1. British trade unions in the early 1970s (March 31, 2016)

2. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s (April 7, 2016)

3. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism (April 13, 2016).

4. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis (April 21, 2016).

5. The 1976 currency crisis (April 26, 2016).

6. The Bacon-Eltis intervention – Britain 1976 (May 11, 2016).

7. The British Cabinet divides over the IMF negotiations in 1976 (June 8, 2016).

8. The 1976 British austerity shift – a triumph of perception over reality (June 13, 2016).

9. The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976 (June 15, 2016).

2008: The major shifts in the gilts market came from the collapse of financial institutions share and the rise in the Bank of England’s share of total debt.

Here is a graph showing monthly bond yields for 10-year British government bonds from February 2008 to February 2021.

Spot the private bond markets losing confidence? You might be better counting the fairies on a pinhead!

Yields didn’t particularly go wildly up and the trend has been firmly downwards. The private investors can’t get enough gilts.

And in closing we get the ‘if’, ‘might’, ‘could’ sort of fear mongering.

Sure, interest rates might go through the roof as inflation accelerates out of control. And then the sky falls in.

Okay, probability very low.

And if, perchance, things turned ugly, the government could just alter the institutional arrangements governing the gilts market and legislate for the Bank of England to take care of things

Conclusion

And in the final sentence you realise Macpherson is of the old Monetarist persuasion and hasn’t kept up with the literature.

He wrote, as if to terminate discussion:

But in the end, expenditure has to be paid for.

Yes it does.

And when the productive resources (and goods and services) respond to the government spending injection, it is at that point that the spending is ‘paid for’.

It is obvious the British government in liaison with its central bank can spend whatever amounts it wants until the end of time. Financially, there is no question about that.

They can put whatever elaborate administrative and accounting hurdles in place as they like, but they cannot alter their intrinsic capacity as the currency-issuer.

What they cannot control, as easily, is the availability of real resources that it needs to conduct its socio-economic policy program.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“1976 – The government lied to the people that it needed to borrow currency from the IMF.”

The root cause of the problem was the UK borrowing in a foreign currency. In June 1976 the UK organised a $5300 million loan facility in US dollars with a basket of foreign nations (including the Fed and the US Treasury), and used it to defend a fixed exchange rate.

By December 1976 the US dollar loan became due, and the rest is history. Or rather mostly myth.

I do worry that it doesn’t matter how much MMT makes sense we have politicians who are very very stupid. They are just fast talkers that talk to our fears not our aspirations. And those who might understand how our money system does work use that knowledge to buy our votes without even considering whether we have the resources or not. And if inflation occurred then it would be MMT that would be blamed not the stupid politicians who used the wonderful possibilities for our countries to their own advantages. Maybe a democratic system is not a suitable system to govern a country properly.

In Australia during the GFC (2008) the public was told constantly (by the then opposition now government) that the stimulus package was profligate spending that would wreck future generations due to increased tax burden on our children.

A ten -year-old in 2008 is now 23 this year and we have had federal govt. tax cuts not increased taxes. How come all our brilliant journalists and politicians never mention this fact?

As I see it, money is just one of a number of similar numerical processes that mankind uses to measure and allocate resources.

Long ago it became obvious that individual specialisation in the tasks that we need to survive on this planet and co-operating to provide mutual benefits led to greater advances in both quality and quantity.

This led to the development of many trades and professions – but the problem arises that the butcher needs bread, the baker need meat and the candlestick maker needed both.

Money is the solution that enables us to measure, allocate and distribute these specialised resources so that we can all lead increasingly better lives.

If I want to build a wooden shed, I use a numerical process called length to measure and allocate the wooden resources (planks) that I need to build my shed.

If I want to bake a cake, I use the similar numerical processes of weight and capacity to measure and allocate the ingredients for the my cake.

Length, weight, capacity and money are all taught side by side as calculations in schools.

Why would that be the case if they were not similar numerical processes utilising different units to meet different needs of measurement and allocation.

@ Patricia Smith

“.. Maybe a democratic system is not a suitable system to govern a country properly…”

Well, if we actually tried meaningful democracy, we might find out. Until then, we only have very brief outbreaks of partial democracy upon which to judge. (But to my mind at least, the results for the labour class were generally very good and socially progressive.)

Without a Fourth Estate (media/information system) fit for purpose, there is no meaningful democracy – voting only affirms the Team A or Team B set of candidates that the propaganda machine of the wealthy elites wants in power to deliver its agenda.

In the UK for example, all mass media platforms peddle a neoliberal right wing agenda in either Tory (Team A) or Tory-lite Labour (Team B) form. And most are quite happy to either legitimise or promote far right ‘populism’, since that splits the labour class & helps to ensure aberrations of genuine left candidates like Jeremy Corbyn can never win power.

Most UK media is owned and controlled by billionaires and millionaires of right wing, or far right, persuasion, and delivers propaganda that advantages capital owner class interests over those of labour. (The BBC is merely a clone of corporate media.)

In my whole lifetime, I have never seen such blatant bias in UK media as that exhibited through the Corbyn years, and especially in the election run up period. We should note also that even the token ‘labour/left’ press, Guardian and Mirror, did all they could to unseat Corbyn as Labour leader from the day he was elected. (No doubt to avoid the charge that *all* media supported the Tories – or LibDems, same thing – the Mirror became the sole Labour backing press during the GE. Guardian’s ‘damning with faint praise’ didn’t qualify as Corbyn supporting either during the election.)

It is no good ignoring the mass media channels’ control of the narrative and pretending that all the electorate need to see is a more persuasive policy choice or improved messaging from the left, – the ‘just one more push’ gambit and surely? the ‘stupid’ electorate will see the merit of our arguments.

Analysing election losses on this same basis, ignoring the fact that the election was nothing more than a measure of efficacy of propaganda control, is equally useless, and a recipe to continue with the fake democracy and lose again.

There are only two, opposing, classes worth primary consideration in society, in the economic interests which drive most citizens’ votes. Capital vs labour. In any mixed economy state, the latter, labour, are always roughly 90% of the population, and by definition in ‘democracy’ should always and overwhelimingly see the their interests prioritised over those of capital.

Yet, near everywhere, throughout the whole history of universal suffrage – and worse today than at any prior time – the reality of interests prioritised by Govs is quite opposite to that which the basic logic of numbers should produce.

In my mind, the primary reason is quite obvious – the power of capital wealth to control mass propaganda, which itself also selects the candidates chosen to be elevated to high influence and office.

Yet, extraordinarily, most actual labour class interests’ advocates still analyse election losses on some basis of failed intellectual arguments, or poor policy proposals, as if the Fourth Estate means of communicating the arguments operated on a free and fair competition (of ideas) basis in presenting them to the general public.

Cognitive dissonance defined imo. We won’t get anywhere until we seriously address this issue alongside challenging the mainstream economics fraud and fakery. And humanity won’t avoid the 6th Great Extinction if we continue with a fake ‘democracy’ system that only works in the interests the tiny minority, wealthy class and their enablers and wannabes.

Mike is right, of course. We only have the democracy which the MSM allows us.

But I have to point out that capital ownership is not the only problem. According to the ONS: “Land accounts for 51% of the UK’s net worth in 2016, higher than any other measured G7 country”. And 1% still own 70% of that land. There is a simple solution but put LVT in your manifesto and the MSM will tear you to pieces.

Yes Mike and Carol, in reality economics is always a class struggle and we can see that in how the media deals with everything. I sometimes wonder if adjectives and adverbs were banned could they still control the way they do now…….

What appears at first glance to be two separate portions of Bill’s post–the first, about a new and more virulent strain of the virus; the second, about how MMT principles are having to be applied, but not acknowledged, to deal with the virus–are inextricably linked. The more virulent virus strain will compel increasing application of MMT principles to deal with it until a tipping point is reached, and mainstream economic thinking will have no option but to openly embrace MMT. No doubt, as already has been indicated, the inevitable mainstream acknowledgment of MMT will be cast in the form of “nothing new here; we knew these things all along.” When you take a step back from the frenzied action of the “tennis match” between mainstream economics and MMT, what you see is that Bill and his colleagues have already aced the serve, and that we’re merely waiting for the umpire to award the point.

When the Troika entered Portugal, invited by the national neoliberal bandits who wanted to go beyond the Troika in 2011, my instincts told me that I was going to suffer from this, and my instincts were correct!

In 2014 my mind fell into a depression, I have been trying to rebuild my mind ever since…

The neoliberal “virus” must be isolated, it’s vicious!

I am very grateful to Bill for the resources he makes available, I have no intention of being an economist, but I’m interested in knowing how the world works.

Bill’s effort and courage in denouncing the neoliberal terrorism has helped me a lot!

Thank you Bill Mitchell!

Yes Carol Wilcox is correct, land ownership was and still is a major problem. During the Industrial Revolution there existed an intellectual elite mainly made up of the sons of the “landed” gentry.

However, did the Industrial Revolution begin on the playing fields of Eton or amongst the dreamy spires of Oxbridge from the efforts of the intellectual elite? No, it began amongst those with little formal education who’s life was centred around doing things rather than simply knowing things. They were potters (Wedgewood), mining engineers (Stephenson & Trevithick), shopkeepers (Lever brothers), wig makers (Arkwright) etc., who received a rudimentary education from relatives or Sunday Schools. Some, like the Quakers (Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry etc.,) were forbidden by their religion from attending university.

However, everything these entrepreneurs made or did was dependent upon the land either to obtain resources from (clay, coal, iron ore, stone, trees wool etc.,) build on or travel across (factories, pot banks, canals, railways etc.,) and the landowners simply collected the “rent” amassing tremendous wealth which, in many cases, was used to gain control of the new industries.

Other countries adopted the new ideas and technology and trained managers to implement it. We were stuck with rent collectors who were “born to rule” and still are!

@Mike Hall

Your comment raises the question of how to make social advances in society given the control the wealthy elite has of media and political parties. Of course the best thing would to wrest control away from them. But while waiting for that day we can make use of divisions between capitalist interests. They exploit divisions in the working class all the time, identity-related divisions being the current favourite.

I have been active in a campaign to include prescription drugs in pubic health care for 16 years in Canada. Currently we have a poor system, not quite as appalling and outright sadistic as the US system, but bad enough. The change we want is supported by 85% of the Canadian public, 100% of the Canadian labour movement and a majority of members of Parliament. On the capitalist side some of the biggest industries are also in favour, most discretely, a few overtly. In a survey 70% of business says it is in favour. However Big Pharma is steadfastly and very actively opposed. The insurance industry is also opposed but has said it could live with the change. So progress is slow, demonstrating the power of a single but very wealthy industry, nonetheless it seems it will happen, although that still remains to be seen.

My point is that while capitalist interests largely run our countries, at times they are divided. Those of us on the other side can exploit their divisions as they do ours. Political maneuvering and improving arguments are important, but political analysis from a class perspective is also essential. Not all capitalists benefit from privatisation and imperialism. There are openings.

Can the concept of the BoE BUYING government debt be put to rest? The BoE doesn’t have any money to BUY anything, It is the most undercapitalised credit issuing bank in the UK. The BoE is simply swapping government bonds back into the “reserves” (previous government spending) that bought them originally. It just shifts the “units of account” from the government’s securities account into the government’s reserve account at the BoE. There is no substantive change in the net units of account in the system.

The BoE QE program entails the BoE issuing £875 billion of CREDIT (LOAN) to a a special purpose vehicle called to APF like any other Bank. It has only bought £20 billion of non-government bonds which had to be funded by the currency issuing Treasury.

The BoE has the ultimate advantage over other credit issuing entities in that its owner, the UK Treasury, has a bottomless pit full of units of account called Pounds Sterling.

Referring to the article, people have this insane standard for socially responsible spending, but absolutely no standard for the stupid stuff we spend money on like football, video games, etc.

The amount of time and money wasted on stupid pointless tasks is absolutely staggering.

How much of the taboo is there because if that is true, then there is no need for economists at all because actual scientists (physicists, biologists etc) can take over since they deal with the physical world. Its all just economists refusing to go to the dustbin of history.

Responding to the comments above, the more the system rots the more people wake up. Capitalism always creates an underclass. That is happening in Britain, Australia and everywhere else. It is inevitable. Even if they turn on the Keynesian pump (which is also a challenge in itself), the newly created money WILL be concentrated into hands of a few, enriching them even further. The superstructure (schools, university, media, companies, parents…) will all continue serve this system and it will rot even further. Once the pain becomes too much, change can happen when people organize and have a clear ideology. Hopefully, the system is pulled out by the roots if the working class leadership is conscious enough for that.

@ Newton E, Finn

I believe that Bill’s opening about another virus is a tongue in cheek reference to the persistent and pernicious mental virus of “Austerity.”

eg, you are correct. I misread Bill’s opening…stupidly. Yet, since new and more virulent strains of the virus are emerging, perhaps my misreading of Bill is not a misreading of bigger picture. Thanks for pointing out my rather embarrassing error.