With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

The mainstream old guard tell it as it is – and how different that is to MMT

While many mainstream economists have been coming out to defend their reputations against the growing awareness that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) presents a direct challenge to their hegemony, some of the mainstream haven’t responded at all and continue to confirm what the standard mainstream macroeconomics is about and how far removed from MMT it really is. The MMT critics claim that there is nothing new in MMT (‘we knew it all along’) in one breathe, and then ‘MMT is crazy dangerous’ in another, without seemingly realising how conflicted that juxtaposition is. But when leading mainstreamers, who are not engaging with the public MMT discussion going on, publish their Op Ed pieces, we gain an insight into what the mainstream is really about despite all the attempts by other mainstreamers to co-opt as much of MMT as they can while still claiming it is crazy. A recent Op Ed article in the Wall Street Journal (March 20, 2019) – The Debt Crisis Is Coming Soon – by Harvard economics professor Martin Feldstein – is a great demonstration of the DNA of mainstream macroeconomics. MMT presents a diametrically opposed view to this standard mainstream analysis. There is no correspondence possible between the two positions.

Background trends

The US Treasury Department released its – Monthly Treasury Statement – on March 22, 2019, which revealed that the US government recorded its largest monthly fiscal deficit in history – $US234 million.

The previous highest monthly deficit was in February 2012 (at the height of the crisis) – $US231.7 million.

Essentially, company taxes have fallen in the last several months, while public spending has risen somewhat.

Of course, claiming that the fiscal deficit is at record levels is rather misleading. It is the same sort of mistake as when politicians claim there is record employment.

In the former case, the size of the economy has probably risen and in the latter case (also impacting on the former), the overall population has probably risen.

The fact is that the fiscal deficit in February 2012 was slightly lower than the fiscal deficit in February 2019 (in $US millions) but over that span of time, nominal GDP has growth by 30 per cent.

Which is why making a song and dance about absolute values can be highly misleading.

The interesting point is that the so-called ‘independent’ central bank once against displayed that it is anything but – with the Chairman berating the government about fiscal matters.

At the most recent Federal Reserve Monetary Policy Committee press conference last week, Jerome Powell said:

I do think that deficits matter and do think it’s not really controversial to say our debt can’t grow faster than our economy indefinitely – and that’s what it’s doing right now … I’d like to see a greater focus on that over time.”

He declined to say when the debt would become a problem – “eventually” was all he said.

Perhaps he might consult the Japanese data. Since the March-quarter 1994, Total Japanese Government debt has risen by 314 per cent while nominal GDP has risen by only 18 per cent clearly violating his warning.

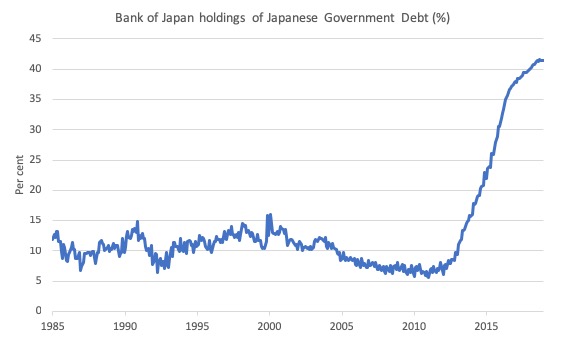

And over that time, the proportion of Bank of Japan holdings of that debt has risen from 11 per cent to 41.5 per cent in the December 2018.

Mainstream economists would have predicted:

1. Rising interest rates.

2. Rising inflation if not hyperinflation.

3. Falling bid-to-cover ratios at government debt auctions.

4. Rising bond yields.

None of which have occurred.

And we have been waiting nearly 3 decades. Are 3 decades, ‘eventually’?

Here is a graph showing the proportion of Japanese government debt held by the Bank of Japan from January 1985 to December 2018.

Yet, as we all know, Japan struggles to get inflation into positive numbers.

If you want to know why MMT is different just ask the mainstream economists to explain that situation.

I read a paper the other day that claiming MMT was deficient because we had no evidence to back up our propositions.

Well, Japan will do for a start before we move on to other nations.

The Feldstein record player is stuck!

And you know what happens when record players get stuck? Just an ugly crackling sound emanates.

I have considered Martin Feldstein views before (for example):

1. Martin Feldstein should be ignored (May 3, 2011).

2. Precarious private balance sheets driven by fiscal austerity is the problem (September 17, 2018).

The problem with Martin Feldstein, mainstream economist and sometime film actor, is that the record has been stuck for decades and he doesn’t see to get that all he produces is noise.

The reference to being a sometime film actor relates to his appearance in the investigative movie – Inside Job – which the Director Charles Ferguson said was about “the systemic corruption of the United States by the financial services industry and the consequences of that systemic corruption.”

As a reminder, I considered his qualification to comment on macroeconomics in this blog post – Martin Feldstein should be ignored (May 3, 2011).

Feldstein, a Harvard economics professor, was a board member of AIG, which was paying massive fees in that role. He was also a board member of the subsidiary company that made all the credit default swaps that bankrupted AIG.

His appearance on the Inside Job was a classic and emphatic example of the disgraceful hubris that the mainstream of my profession exuded then, and now.

No-one could take him seriously after that appearance.

He consistently writes these inflammatory Op Eds – which predict doom.

It seems that he has little memory for what he does write. Things never turn out the way he predicts, yet he bobs up sometime later, predicting the same and so it goes.

It is as of he just uses some search find/replace function to update the dates and some numbers – and out pops another Op Ed.

And time passes, his predictions are never realised, and so it goes.

His Op Eds also display a callous lack of empathy, which is somewhat characteristic of mainstream macroeconomics, when it is required to address human issues rather than those relating to their beloved ‘infinitely lived representative agent’.

For example, on July 22, 2010, when the world economy was mostly in recession or fragile recovery, the Financial Times published an Op Ed from Feldstein – A double dip is a price worth paying – where he defended the Eurozone austerity and argued that governments should be:

… seizing the current moment of crisis to take politically difficult budget actions.

I am sure he wouldn’t have been recommending this policy strategy had his job and pension entitlements been directly linked to the unemployment that the austerity caused, and which still endures.

Feldstein wrote (at the height of the crisis) that:

Immediate action is necessary to make future deficit cuts credible. And painful cuts in government pensions and in public payrolls as well as increases in personal taxes may only be possible while there is a sense of crisis throughout Europe.

Unfortunately, the front-loaded deficit reductions may push economically weak countries into recession for the next year or two. That is the cost of achieving the needed long-term deficit reduction in the current economic and political environment.

At least he understood that the narratives at the time put out by the European Commission, IMF and a range of economists that “the front-loaded fiscal deficit reductions will not weaken the economy in the short run” were probably wrong and that the likely result would be “double dip downturns that raise unemployment”.

But he was recommending that governments deliberately increase unemployment in order to move closer over time to some arbitrary fiscal number.

The concept of fiscal policy loses all meaning if governments use it in this way. Its purpose and strength is to ensure there is low unemployment among other things.

The actual numbers – of the deficit and the debt (if government maintain the historical convention) – are irrelevant if public welfare is being maximised.

The idea that a government would use its fiscal instruments to generate about the worst evil in our economic lives (unemployment) is so far removed from responsible and ethical conduct that one just shudders with the thought.

But Feldstein has made a career in recommending this sort of policy abuse.

At regular intervals in the period since he has written variations on that theme – that the public debt will explode and the deficits will become unfundable – and then all manner of pestilence will ensue.

He recently wrote a Wall Street Journal article (June 10, 2018) – The Fed Can’t Save Jobs From AI and Robots – which ran the line that Artificial Intelligence and Robots will create mass unemployment in the US (millions will become unemployed as a consequence) but the central bank should not deviate from maintaining low inflation.

His solution is that government should further deregulate the labour market (cut wages) rather than try to engage in demand stimulus to generate higher labour demand.

On September 17, 2018), he was mentioned in a news report – ‘We don’t have any strategy to deal with it’: experts warn next recession could rival the Great Depression – as saying:

We have no ability to turn the economy around … When the next recession comes, it is going to be deeper and last longer than in the past. We don’t have any strategy to deal with it … Fiscal deficits are heading for $US1 trillion dollars and the debt ratio is already twice as high as a decade ago, so there is little room for fiscal expansion.

Of course, none of this Feldstein nonsense ever turns out to be correct.

As I explained in these blog posts – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still! (October 11, 2010) and The government has all the tools it needs, anytime, to resist recession (August 20, 2016) – a currency-issuing government can always attenuate the impacts of a financial crisis that has its origins in a non-government spending collapse.

This capacity is independent of what policy positions the same government has run prior to the crisis. Any notion that a running a deficit now (of any scale) in some way reduces the capacity to run a similar scale deficit in the future is plain wrong.

There is not even a nuance that we can bring to that proposition – a conditionality. Plain wrong is plain wrong.

When Feldstein is saying that “there is little room for fiscal expansion” he is just rehearsing the fake knowledge of the mainstream economists who define fiscal space in circular terms.

Sort of like this:

1. Fiscal expansion can only occur if deficits and debt ratios are low.

2. Currently deficits and debt ratios are higher than they were at some point in the past.

3. Therefore we have run out of fiscal space.

A circular, self-referencing proposition. Which begins wrongly and thus concludes wrongly.

If there is a new crisis, then there will be massive fiscal space which will be defined by the idle resources in the non-government sector that have become unemployed because non-government spending collapses.

That is the only way in which we can talk about ‘fiscal space’. If there are productive resources that are idle and available to be brought back into productive use, then there is fiscal space.

The fact is that there is no crisis large enough that the government through appropriate fiscal policy implementation cannot respond to.

There is no non-government spending collapse big enough that the government cannot maintain full employment through appropriate fiscal policy implementation.

A currency-issuing government can always use that capacity to buy whatever idle resources there are for sale in the currency it issues, and that includes all idle labour.

A currency-issuing government always chooses what the unemployment rate will be in their nation.

If there is mass unemployment (higher than frictional – what you would expect as people move between jobs in any week), then the government’s net spending (its deficit is too low or surplus too high).

I explain the so-called helicopter money option in this blog (also cited above) – Keep the helicopters on their pads and just spend (December 20, 2012).

By way of summary (although I urge you to read that blog post if you are uncertain):

1. Introducing new spending capacity into the economy will always stimulate demand and real output and, as long as there is excess productive capacity, will not constitute an inflation threat.

2. When there is weak non-government spending, relative to total productive capacity (and unemployment) then that spending capacity has to come from government.

3. The government can always put the brakes on when the economy approaches the inflation threshold. I will consider the ‘government isn’t nimble enough’ myth, which is regularly wheeled out against MMT, in a forthcoming blog post.

4. A currency-issuing governments does not have to issue debt to match any spending in excess of its tax receipts (that is, to match its deficit) with debt-issuance. That is a hangover from the fixed-exchange rate, convertible currency era that collapsed in August 1971.

5. Quantitative easing where the central bank exchanges bank reserves for a government bond – is just a financial asset swap – between the government and non-government sector. The only way it can impact positively on aggregate demand is if the lower interest rates it brings in the maturity range of the bond being bought stimulates private borrowing and spending.

6. But non-government borrowing is a function of aggregate demand itself (and expectations of where demand is heading). When elevated levels of unemployment persist and there are widespread firm failures, borrowers will be scarce, irrespective of lower interest rates.

7. Moreover, bank lending is not constrained by available reserves. QE was based on the false belief that banks would lend if they had more reserves.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit (December 13, 2009) and Building bank reserves is not inflationary (December 13, 2009) – for further discussion.

8. Governments always spend in the same way – by issuing cheques or crediting relevant bank accounts. There is no such thing as spending by ‘printing money’ as opposed to spending ‘by raising tax receipts or issuing debt’. Irrespective of these other operations, spending occurs in the same way every day.

9. A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

10. If the government didn’t issue debt to match their deficit, then like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

11. Taxation does the opposite – commercial bank assets fall and liabilities also fall because deposits are reduced. Further, the payee of the tax has decreased financial assets (bank deposit) and declining net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

12. A central bank can always credit bank accounts on behalf of the treasury department and facilitate government spending. This is the so-called ‘central bank financing’ option in textbooks (that is, ‘helicopter money’). It is a misnomer.

And the point is that all this talk of sovereign debt crises and the central bank running out of firepower is actually raising the probability of a renewed financial crisis emanating from the non-government sector, which is clearly, despite all the myths that have been told, was the source of the GFC.

Fast track to last week.

Feldstein was at it again.

His Wall Street Journal Op Ed (March 20, 2019) – The Debt Crisis Is Coming Soon – To avoid economic distress, the government has to reduce future entitlement spending (you need a subscription) – ran the same flawed train of logic but this time was attacking pension and social security entitlements.

You start to see the pattern.

His Op Eds present the same faux crisis argument and then propose a solution ranging from making more people unemployment, cutting wages, cutting pensions, cutting welfare entitlements and so it goes.

Anything that helps ordinary workers endure capitalism is shunned as creating a crisis.

In his latest Op Ed, he says:

The most dangerous domestic problem facing America’s federal government is the rapid growth of its budget deficit and national debt.

The only crisis surrounding the fiscal aggregates is that they are so badly misunderstood and manipulated by the likes of Martin Feldstein to create austerity and poverty.

He tells his readers – in numbers how the deficit will rise on current indications “to about 5% of GDP 10 years from now” and the debt ratio will follow it up.

Is a 5 per cent fiscal deficit scary or bad?

Nothing can be said without a context.

If the non-government sector wanted to claim more of GDP via its spending decisions, than a 5 per cent fiscal deficit would allow, then that would imply that nominal spending in the economy would be too strong relative to available real output.

That would be problematic and would have to be resolved by reducing the non-government spending claim on available real goods and services and/or reducing the government claim.

Without the context, Op Eds that merely rehearse ‘big’ numbers are meaningless distractions.

He goes on to claim that in an environment of a rising debt ratio:

When America’s creditors at home and abroad realize this, they will push up the interest rate the U.S. government pays on its debt. That will mean still more growth in debt. A 1% increase in the interest rate the government pays on its debt would boost the annual deficit by more than 1%. The higher long-run debt-to-GDP ratio would crowd out business investment and substantially reduce the economy’s growth rate. That in turn would mean lower real incomes and less tax revenue, leading to-you guessed it-an even higher debt-to-GDP ratio.

And all the usual mainstream textbook mumbo jumbo fake knowledge.

The Federal Reserve sets the interest rate.

While the bond markets can set yields on government debt only if the government allows that to happen.

And crowding out is a mainstream concept that is logically incoherent and empirically bereft.

The Bank of Japan has not struggled to keep interest rates at zero even when the debt ratio escalated. All central banks have that capacity.

But the real agenda of the Op Ed is to advocate cuts in spending (raising taxes is eschewed) and because:

Defense spending and nondefense discretionary outlays can’t be reduced below the unprecedented and dangerously low shares of GDP that the CBO projects …the only option is to throw the brakes on entitlements.

So if Martin Feldstein had his way he would create a trail of unemployment, workers on poverty wages, and manifestly reduced and delayed pensions once they could no longer work.

Make America Great Again it seems.

I also note that the likes of Paul Krugman has even critised Feldstein in a four-Tweet response (you can go to his Twitter page if you care).

Well it wasn’t all that long ago that Paul Krugman was dishing up this stuff out too.

In the late 1990s, for example, Paul Krugman made embarassingly wrong statements about the Japanese economy.

He advised the Bank of Japan to embark on large-scale quantitative easing in order to increase the inflation rate.

As Richard Koo noted in his 2003 book – Balance Sheet Recession: Japan’s Struggle with Uncharted Economics and its Global Implications:

Western academics like Paul Krugman advised the BOJ to administer quantitative easing to stop the deflation. Ultimately – and reluctantly – the BOJ took their advice, and in 2001 the Bank expanded bank reserves dramatically from ¥5 trillion to ¥30 trillion.

Nonetheless, both economic activity and asset prices continued to fall, and the inflation projected by Western academics never materialized.

Paul Krugman’s diagnosis of the Japanese situation was completely wrong at the time.

I discuss those issues in this blog post – Balance sheet recessions and democracy (July 3, 2009).

So it is interesting that he is now trying to distance himself from the basic predictions that a New Keynesian macroeconomics framework would deliver (as in Feldstein’s Op Ed).

He is clearly trying to reposition what he sees as the mainstream macroeoconomics. But that process leaves him with little credibility given his past comments.

Conclusion

While key mainstream macroeconomists are trying to nuance their message in the face of the degenerative nature of their paradigm, the old guard, like Martin Feldstein, keep pumping out the basis theory and its predictions.

It allows us to see what the core theory without all the ad hoc qualifications and fudges is about.

And that allows us to see how different Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is to the mainstream.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

And let’s not forget Steen Jakobsen, chief economist at Saxobank, who says:

“For the record, MMT is neither modern, monetary nor a theory. It is a the political narrative for use by central bankers and politicians alike. The orthodox version of MMT aims to maintain full employment as its prime policy objective, with tax rates modulated to cool off any inflation threat that comes from spending beyond revenue constraints (in MMT, a government doesn’t have to worry about balanced budgets, as the central bank is merely there to maintain targeted interest rates all along the curve if necessary). Most importantly, however, MMT is the natural policy response to the imbalances of QE and to the cries of populists. Given the rise of Trumpism and democratic socialism in the US and populist revolts of all stripes across Europe, we know that when budget talks start in May (in Europe, after the Parliamentary elections) and October (in the US), governments around the world will be talking up the MMT agenda: infrastructure investment, reducing inequality, and reforming the tax code to favour more employment at the low end.”

But wait, it gets better:

“My economic studies really only taught me three useful things (but then, I’m a terrible economist):

The yield curve is never wrong.

Say’s law (supply creates its own demand).

Productivity is everything.”

Cheers! Hope you had a good belly laugh.

I really hate when Bill was right and I was wrong. I’d think I would be used to it by now, but no- I still hate it. I never had much hopes for Martin Feldstein but I did think that someone like Paul Krugman would either discover the flaws (if any) in MMT and point them out or, failing that, at the very least represent MMT honestly in their writings. But no. Instead we get surveys with sham questions that purport to represent MMT. And numerous statements that what MMT says about this or that is ‘just wrong’ as though that is some kind of economic argument in and of itself. Garbage is what that is.

But I guess more of them are finding they now need to address MMT in some way- even if it is just to make false statements and fake arguments. Maybe that’s a good thing sort of. Very few have done themselves proud though.

Great post (as always) and superb summary of the basic issues relating to fiscal capacity, interest rates and full use of Japan as the anti-mainstream ‘laboratory experiment.’

Great to see all this well expressed in the new Macroeconomics book. Hopefully the book will be filtering through to Universities in the coming years.

I was hoping change would come quicker but I am beginning to accept it will take some years and probably another crash.

Dear Bill,

I’m not an accountant or an economist, but are you sure that the Feb US deficit was only $234 million? That would extrapolate to an annual deficit of about $2.8bn – certainly nothing to get very excited about!

Looking at the diagram Figure 1. on p.4 of the US Treasury Monthly Statement, the stated Feb deficit is shown as $234 billion.

It’s confusing though, because Table 1. (and Table 2.) on p.5 does indeed title the columns in ‘millions’, with figure of ‘234’ shown in the deficit column for Feb 2019.

Forgive me if I’m wrong (who am I to correct the US Treasury!), but I think those might be misprinted titles on the p.5 tables, which should in fact read hundreds of billions?

And if so, you might want to revise your quoted figures!

Best, MrS

Hi Bill

I copied you in to an email I sent to Gillian Tett today. I gave a link to your blog. I do hope she reads today’s as she ‘starred’ alongside Feldstein in ‘Inside Job’, I believe.

MMTler often evoke Japan, with its combination of a high public debt-ratio, low interest rates and low inflation as evidence that high public debt is not harmful or positively beneficial. I don’t think this example is valid.

1. Japanese interest rates are low, because the country has a large positive international investment position (accumulated current account surpluses).

2. Japanese inflation is low, because nominal and real interest rates are low – nominal rates are low because of low inflation and real rates are low because of the low growth potential.

Hence, the real question is why is the growth potential so low in Japan. The answer is – according to Japan-experts like Richard Koo – that over the past 30 years, the government has prevented unsustainable investments from being liquidated. Excessive government spending has kept “Zombie” firms alive that should have gone out of business years ago.

Dear Carol and Bill,

Can you share Gillian’s response? Curious to know what the FT columnist thinks of Feldstein.

Cheers,

Sanjay

I read The Jungle over the weekend.

I realize that MMT is a lens that allows one to implement programs like JG to continue the work to fix massive failings of the market that grind regular people to dust.

As for mainstream economists, Upton Sinclair once said:

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”

Bill says, “The government can always put the brakes on when the economy approaches the inflation threshold. I will consider the ‘government isn’t nimble enough’ myth, which is regularly wheeled out against MMT, in a forthcoming blog post.”

To many people the government’s dexterity in dealing with the threat of inflation encapsulates the difference between MMT (in its theoretical form) and its practical application.

Bill will recall the drama of the inflationary 1970’s – he may also be familiar with the Inflation Workshop of Manchester University, which at its outset included a range of political persuasions. Professor Peter Parkin for insatnce, was a self-confessed Keynsian who believed changes in taxation and government spending were more effective ways of controlling the economy than changes in interest rates and the money supply. Not all members were out-and-out monetarists.

The control of the money supply became paramount however, even if this necessitated periods of unemployment above the “natural” rate – with the Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) designed to bring down inflation to manageable levels (over maybe a 5 year period), with its attendant employment disruption.

Which leads me to Bill’s proposed blog tackling the government’s nimbleness over economic policy. This seems an ideal opportunity for Bill to describe how MMT principles work in practice – yet, what appears to be a straightforward emphasis on practical MMT implementation can create problems; worker unrest due to changes in industrial scale, skills and location that are drawn out over time have in the past led to instances where entrenched views of (understandably) vested interests are difficult to accommodate. If many of these changes are linked to government financed organisations the problem can be accentuated – was not the size of the public sector a factor in monetary growth in the 1970’s?

@Sanjay Mazumdar: Gillian sent this reply to my first email: “Fascinsting [viz] – thanks! It is not a topic I know much about right now but should do so will look..!”.

I wouldn’t expect another – was amazed to get this.

Bill, another example of the old guard paradigm at work:

Oliver Letwin, a senior member of the British Conservative Party, took part in a parliamentary debate on the Brexit crisis in London this evening. In his remarks, Letwin said the UK “faced another cliff edge” in 2010, when “we were within days of the Bank of England discovering that our creditors would not finance the UK any more”.

The country had just held a general election but no party had emerged with a majority.

“We were very heavily indebted due to what had happened in 2008 (the GFC) and what we were told by the Governor of the Bank of England was that if a coalition was not formed pretty quickly, he personally felt that the lenders would go on strike and we would have a meltdown”.

Letwin didn’t explain what a “meltdown” would involve or why it would take place.

As any student of Bill’s knows, the creditors of a government which issues its own currency (with a floating exchange rate and no foreign currency debt) cannot “go on strike” by refusing to “finance” that government, because the central bank can always step into the breach.

Melvyn King was then Governor of the Bank of England; he’s currently teaching economics in New York. Letwin himself is a former banker.

(Letwin went on to say that in 2010 he and a few other politicians were able to create the framework for a coalition government in just four days – even though top civil servants thought it would be impossible – and that politicians could also solve the Brexit crisis if they put their minds to it.)

Great article – as always a tasty “truth sandwich.”

Eagerly awaiting my textbook. Time to really knuckle down in a systematic way and work through all the topics more thoroughly.

Mr Shigumitsu seems to be correct in diagnosing a typo of M for B.

I am quite interested by this example of Japan, that (nominally at least) has low unemployment (they do also suffer underemployment, 2018 LU4 rate 5.9%), high and still increasing per capita “real”/PPP GDP, and of course the scary levels of debt and an older “less productive” population, which most Western countries are also looking forward to (viz “big Australia” arguments).

Dear Dr. Dirk Faltin (at 2019/03/25 at 10:12 pm)

Japanese interest rates are low because the Bank of Japan conducts monetary operations to keep them that way – maintaining sufficient liquidity in the cash system to allow the interbank market to operate to drive rates down. It has nothing to do with the difference between Japan’s gross and net debt position.

Further, Richard Koo does not endorse fiscal austerity. His whole thesis is predicated on the ineffectiveness of monetary policy and the need for extended fiscal policy support to income to allow the non-government sector to restructure its balance sheet away from debt.

best wishes

bill

The Letwin statement last night was a cheap shot. The GFC occurred 2008 and Brown and Darling had got on top of it although they could have done more. By 2010 when the election was held recovery was starting. The Tories killed it stone dead. I watched the debate and most of it was typical British Tory pomposity but I knew then that all those criticising her would fall in line if a confidence vote were held. There is no hope for Britain. We might be better off outside the EU but who in their right mind would trust these shysters to do it.

@David Duffy,

Thanks.

I think the misunderstanding is due to reading the comma in Tables 1 & 2 as a decimal point.

(So it’s 234,xxx million dollars, not 234.xxx million dollars)

Easily done on small devices!

Who indeed. That was probably one of the reasons that some normally Eurosceptic people reluctantly voted “Remain” (I probably come into that category; I reluctantly, and only with a heavy heart voted Remain, and almost immediately regretted it).

With hindsight, however badly a Tory government was going to handle Brexit (and they have exceeded anyone’s worst expectations), and however badly a right-wing, post-EU Tory government would treat the non-privileged majority of the country, this was our last chance to leave the EU, at least for the foreseeable future. So we had to take it.

Except that it’s not now going to happen. (That would still be my reading of the situation). Or if it happens, it would actually be done in such a way that it was worse than staying in. (Because (a) no influence in Brussels/Strasbourg once no longer a member and (b) no actual mechanism for “getting out” – The TM “deal” includes no equivalent of Article 50, I believe), and I doubt if anything our pathetic bunch of Remainer MPs can spatchcock together will include one, either.

Yeah, I have always wondered how the right can possibly do a brexit that works when I don’t trust them to do anything in the US.

I am sry for my friends in the UK.

I’m still unwinding the entanglement that surrounds MMT explanations of broad-money outcomes and its mainstream version.

In particularly, I have unearthed Bill’s series on “Modern monetary theory and inflation”. This enquiry then led me to his piece “Deutsche Bundesbank exposes the lies of mainstream monetary theory” which included the statement attributed to the B of E …”modern central banks target interest rates, and are committed to supplying as many reserves (and cash) as banks demand at that rate, in order to safeguard financial stability. The quantity of reserves is therefore a consequence, not a cause, of lending and money creation.”

We all knew this didn’t we.

That still doesn’t explain how the Barber and Lawson booms came about or were allowed to create so much chaos. Tim Congdon, a Monetarist commentator of that period puts the blame squarely on the negligent expansion of the money supply, which suggests a basic misunderstanding of monetary economics – or was it just a case of interest rates being held too low for political reasons (and what about B of E independence).

A little further research is needed.

@Gogs,

Not sure about the Lawson boom, but with the Barber boom (aka “dash for growth”, IIRC) was probably a combination of low interest rates, and taking controls off (commercial) bank lending, and probably encouragement to commercial banks behind the scenes to let rip.

I seem to remember that in the 1950s and for at least some of the 1960s, commercial bank lending was controlled to varying extents by the BoE. Barber almost certainly told the BoE (no pretence at independence in those days) to relax controls on commercial banks.

While it’s true of course that just increasing the money supply does not of itself create inflation (since, as Bill tells us, it is the actual spending which does that), encouraging bank lending is effectively encouraging spending, and it was probably consumer spending, rather than spending to increase the productive capacity of the economy.

This was an era when many people were getting bank accounts for the first time (I was one of them); and bank loans became more common among “ordinary people”. (Before that they would have gone for Hire Purchase).

I would hazard a guess that the Lawson boom was to do with the explosion of bank credit into the housing market. Lawson let the banks into the mortage business. Previously mutuals were the main providers. Homebuying led to a consumer boom, with owners using their home as collateral for consumer borrowing – often as part of the mortgage meant for enhancements to the house but commonly used to buy a new car as well. But Lawson did one good thing: he, gradually, abolished MIRAS (Mortgage Interest Relief At Source). During part of that process there was a temporary boost to house prices when unmarried couples were given the chance for 6 months to fix their double MIRAS benefit. House prices peaked at that time and then turned sharply down. This was predicted to happen by the land value tax movement who believe in a land price cycle of about 18 years. Fred Harrison was pretty accurate when he predicted the peak of the land market as end 2007 in Boom Bust: House Prices, Banking and the Depression of 2010. (Not that I believe them!)

In reply to myself @2019/3/25 at 14:39

It appears that maybe mainstream economists are realizing that saying MMT is ‘just wrong’ is really not much of an argument.

Brad Delong decided to innovate yesterday- “To the extent that there is a substantive difference between JG and FF, FF is better. Full stop. This is a substantive difference, not a political slogan.

You are not adding value, and you have used up your welcome here.”

See- he changed it up. “Full stop. This is a substantive difference”. Wow- just so much more informative than “just wrong”! Innovation like this is bound to make a substantive difference any day now. ‘Substantive difference because I say so’ is much better than ‘Just wrong because I say so’. Has more ‘substance’ in it I guess.

Bill was right about these guys. They are not really willing to discuss MMT for the most part. They really aren’t interested in considering MMT arguments. That Brad Delong actually mentions FF (functional finance) is probably due to exposure to MMT arguments in the first place though. And seeing him as the defender of functional finance against a barbaric MMT advocate like myself is so ironic that it is just bizarre. As if MMT has been disparaging functional finance while Brad Delong has all along been its true advocate and defender. Just wacko.

Jerry Brown:- ” As if MMT has been disparaging functional finance while Brad Delong has all along been its true advocate and defender. Just wacko”.

Agreed.

But it seems yet more bewildering even than that. An intrinsic ingredient of Lerner’s “FF” was (by analogy with the central bank acting as lender of last resort) govt acting as employer of last resort. (Or am I hallucinating? … must stop smoking that weed …).

If so anyone subscribing to the premises of FF is accepting the JG by another name. de Long is doing just that while at the same time professing to reject JG unreservedly. He’s flatly contradicting himself, isn’t he? What nuance am I missing?

Well Robert, this is what I wrote to Brad-

“You [Delong] ask- “How is saying that the most important task of the government is to buy enough things to get the economy to full employment different from saying that the most important task of the government is to employ enough people to get the economy to full employment?”

In my opinion, the difference is due to the nature of the Job Guarantee proposal. The JG proposes that the government hire off the ‘bottom’ of the potential labor pool at a set minimum wage offer. These would mostly be people for whom there is currently no private job offers for their services at that set wage. As in the government is not competing at ‘market’ rates in offering this employment. MMT economists call this a ‘loose’ full employment scenario. The idea is that this would be a much less inflationary way to spend than if the government desired to spend enough to create full employment through its normal budgeting process where it competes at market rates for goods and the services of people, many of which may already be employed in the private sector doing productive things at high wage rates. You might see inflation get out of hand before you reach full employment.

So it matters what the government is spending on- that is the difference. Try to create full employment by competing with the private sector for already employed resources you will drive prices up. By offering employment at a decent minimum wage to those who want to work for that wage- well not so much is the theory. In my opinion.”

This was his reply-“Job Guarantee: “Our policy is for the government to run a deficit to offer low-quality make-work low-pay jobs that suck” is really stupid on many levels. Functional Finance: “Our policy is for the government to run a deficit so that the labor market is in balance with employers getting the most value for their money possible and workers getting the most money for their time and energy possible with unemployment reduced to a ‘frictional’ level’ is really smart. Put me down for Functional Finance, Alex, and make it a true daily double…”

It degenerated from there. He apparently thought his reply was so witty that he called it his ‘comment of the day’ and made a separate blog post out of it.

Robert, in case my point was unclear, (Delong apparently didn’t understand it or decided to misrepresent it) I will copy how someone named Will summarized it in a comment that I believe has been deleted by Delong. Thank you Will.

will said…

Jerry Brown, and Randy Wray’s, point is that increasing government spending on goods and services until full employment is reached has much more potential for causing inflation than a job guarantee.