In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Precarious private balance sheets driven by fiscal austerity is the problem

The media has been giving a lot of attention in the last week to the 10-year anniversary of the Lehman Brothers crash which occurred on September 15, 2008 and marked the realisation, after months of denial, that there was a financial crisis underway. Lots of articles have been published recently about what we have learned from this historical episode. I thought that the Rolling Stone article by Matt Taibbi (September 13, 2018) – Ten Years After the Crash, We’ve Learned Nothing – pretty much summed it up. We have learned very little. Commentators still construct the crisis as a sovereign debt problem and demand that governments reduce fiscal deficits to give them ‘space’ to defend the economy in the next crisis. They are also noting that the balance sheets of the non-government sector components – households and firms – are looking rather precarious. They also tie that in with flat wages growth and a run down in household saving. But the link between the fiscal data and the non-government borrowing data is never made. So we are moving headlong into the next crisis with very little understanding of the relationship between government and non-government. And we are increasingly relying on private sector debt buildup to fund growth as governments retreat. Everything about that is wrong.

The recently published book – Financial Exposure: Carl Levin’s Senate Investigations into Finance and Tax Abuse (Palgrave Macmillan) by Elise J. Bean is worth reading. Elise Bean was an investigative lawyer for the US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI).

The book recounts the workings of the PSI.

We read that the PSI has:

… faced down corrupt bankers, arrogant executives, and sleazy lawyers. We’d confronted tax dodgers of all stripes, from billionaires to multinationals. We’d interviewed crooks in prison, North Korean representatives, and tax have operatives. We’d protected whistleblowers, championed victims, and defended honest government employees battling abuses. We’d stood up to dirty tricks, assaults on PSI’s bipartisanship, and attacks on our bosses.

Never was this environment more loaded than when they started looking into the financial services sector.

The chapter on “Deconstructing the Financial Crisis” is particularly interesting, given the current attention the decade-anniversary is receiving.

Elise Bean writes that the investigation was “the longest, toughest inquiry” the PSI under Carl Levin had ever undertaken.

The “facts were tangled, the players powerful, and the stakes huge”.

She credits the legislative action that led to the “Dodd-Frank Act, the most extensive set of U.S. financial reforms in a generation” as the results of their investigation.

The book leaves no doubt as to what caused the GFC – and the train wreck of Lehmans and others had been gathering pace for a few decades as a result of the neoliberal-inspired deregulation and reduced oversight (mostly due to regulative capture).

The crisis saw governments offer trillions to the otherwise failed big banks and related institutions to keep them alive. Those bailouts have had long-term consequences that Matt Taibbi documents.

1. “a radical transformation of the economy”.

2. “Previously, small banks traditionally enjoyed a lending advantage because of their on-the-ground relationships with local businesses. But the effective merger of the state with giant, too-big-to-fail banks has tilted the advantage far in the other direction.”

3. “Big banks post-2008 could now borrow much more cheaply than smaller ones, because lenders no longer worried about them going out of business.”

4. “How much of the record $171.3 billion in profits earned by banks in 2017 was owed to the implicit guarantee?”

5. “The bank-state merger brokered 10 years ago this week socialized the risks of the financial sector, and essentially converted Wall Street into a vehicle for annually privatizing a big chunk of America’s GDP into the hands of a few executives.”

And so on.

But if we thought there might be a change in behaviour afterwards (for example, because of Dodd-Frank) we would be wrong.

The scandals have keep coming.

1. The 2010 “flash crash” of the New York Stock Exchange as a result of some rogue traders on Chicago’s derivatives exchange – see The 2010 ‘flash crash’: how it unfolded.

2. The LIBOR scandal – see Libor scandal: the bankers who fixed the world’s most important number rigging HSBC’s $850 million drug money-laundering fiasco

3. HSBC getting caught laundering drug money from Mexico, among other criminal acts – see – HSBC to pay $1.9 billion U.S. fine in money-laundering case

4. Australian readers who have been following the Royal Commission into the financial services sector will be able to catalogue a sequence of criminal acts by bankers, insurance companies etc. Charging fees for no service, cheating customers, etc.

I saw a Tweet last week listing the top 10 financial market players who had gone to prison for their criminal conduct.

The list looked like this (first three only):

1.

2.

3.

etc

In other words, no-one went to prison for their criminal behaviour.

In the recent German TV series, Bad Banks, the major character tells her boss who is about to go down for criminal behaviour that no-one at his level goes to prison.

Matt Taibbi lists other legacy issues arising from the lax way governments dealt with the crisis.

1. “we made Too Big To Fail worse by making the companies even bigger and more dangerous”.

2. “The people responsible for the crisis weren’t just saved, but made beneficiaries of another decade of massive unearned profits”.

I was reading Elise Bean’s book around the same time I was alerted to an Irish Times article (September 13, 2018) – Trader blows €100m hole in Nasdaq’s Nordic power market – which reported that one of the highest earning Norwegian financial market trader had just severely compromised the “stability fund that ensures the safety of derivatives trading in European electricity markets.”

What?

This character was betting on “European power markets” and:

… saw his positions collapse on Monday after extreme market moves in German and Nordic energy markets … [he] … had defaulted on Tuesday after they were unable to meet margin calls at its clearing house on loss-making trades … [he] … blew through several layers of safeguards designed to protect it from such losses …

The size of the loss also ate up about two-thirds of a separate €166 million mutual default fund members must contribute to …

And “some of the biggest banks and energy traders such as Morgan Stanley, UBS and Equinor, Norway’s state oil company” will have to make up the losses to the clearing house.

Power is an essential service to communities. Yet, we still allow the financial market casino to bet on it and compromise the stability of the financial system as a consequence.

Enron went bankrupt in 2001.

Australia had power cuts in 2017 because the financial arms of the privatised (previously state-owned) energy companies arranged for generating capacity to be turned off so they could profit on the spikes in the energy prices.

And so it goes.

And one of the most powerful narrative that still remains is somehow that governments have to pursue fiscal surpluses to safeguard our financial system – to give them the ammunition to defend the economy from meltdown.

Just this week, economists are coming out claiming there is no government capacity ‘left’ to prevent another crisis.

Remember Martin Feldstein’s appearance in the investigative movie – Inside Job – which the Director Charles Ferguson said was about “the systemic corruption of the United States by the financial services industry and the consequences of that systemic corruption.”

As a reminder, I considered his qualification to comment on macroeconomics in this blog post – Martin Feldstein should be ignored (May 3, 2011).

Feldstein, a Harvard economics professor, was a board member of AIG, which was paying massive fees in that role. He was also a board member of the subsidiary company that made all the credit default swaps that bankrupted AIG.

His appearance on the Inside Job was a classic example of the disgraceful hubris that the mainstream of my profession exuded then, and now.

He recently wrote a Wall Street Journal article (June 10, 2018) – The Fed Can’t Save Jobs From AI and Robots – which ran the line that Artificial Intelligence and Robots will create mass unemployment in the US (millions will become unemployed as a consequence) but the central bank should not deviate from maintaining low inflation.

His solution is that government should further deregulate the labour market (cut wages) rather than try to engage in demand stimulus to generate higher labour demand.

In an article published today (September 17, 2018) in the UK Daily Telegraph (but syndicated to Fairfax) – ‘We don’t have any strategy to deal with it’: experts warn next recession could rival the Great Depression – Feldstein is quoted as saying:

We have no ability to turn the economy around … When the next recession comes, it is going to be deeper and last longer than in the past. We don’t have any strategy to deal with it … Fiscal deficits are heading for $US1 trillion dollars and the debt ratio is already twice as high as a decade ago, so there is little room for fiscal expansion.

Of course, none of this Feldstein nonsense is remotely correct.

As I explained in these blog posts – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still! (October 11, 2010) and The government has all the tools it needs, anytime, to resist recession (August 20, 2016) – a currency-issuing government can always attenuate the impacts of a financial crisis that has its origins in a non-government spending collapse.

This capacity is independent of what policy positions the same government has run prior to the crisis. Any notion that a running a deficit now (of any scale) in some way reduces the capacity to run a similar scale deficit in the future is plain wrong.

There is not even a nuance that we can bring to that proposition – a conditionality. Plain wrong is plain wrong.

When Feldstein is saying that “there is little room for fiscal expansion” he is just rehearsing the fake knowledge of the mainstream economists who define fiscal space in circular terms.

Sort of like this:

1. Fiscal expansion can only occur if deficits and debt ratios are low.

2. Currently deficits and debt ratios are higher than they were at some point in the past.

3. Therefore we have run out of fiscal space.

A circular, self-referencing proposition. Which begins wrongly and thus concludes wrongly.

If there is a new crisis, then there will be massive fiscal space which will be defined by the idle resources in the non-government sector that have become unemployed because non-government spending collapses.

That is the only way in which we can talk about ‘fiscal space’. If there are productive resources that are idle and available to be brought back into productive use, then there is fiscal space.

The fact is that there is no crisis large enough that the government through appropriate fiscal policy implementation cannot respond to.

There is no non-government spending collapse big enough that the government cannot maintain full employment through appropriate fiscal policy implementation.

A currency-issuing government can always use that capacity to buy whatever idle resources there are for sale in the currency it issues, and that includes all idle labour.

A currency-issuing government always chooses what the unemployment rate will be in their nation.

If there is mass unemployment (higher than frictional – what you would expect as people move between jobs in any week), then the government’s net spending (its deficit is too low or surplus too high).

I explain the so-called helicopter money option in this blog (also cited above) – Keep the helicopters on their pads and just spend (December 20, 2012).

By way of summary (although I urge you to read that blog post if you are uncertain):

1. Introducing new spending capacity into the economy will always stimulate demand and real output and, as long as there is excess productive capacity, will not constitute an inflation threat.

2. When there is weak non-government spending, relative to total productive capacity (and unemployment) then that spending capacity has to come from government.

3. The government can always put the brakes on when the economy approaches the inflation threshold.

4. A currency-issuing governments does not have to issue debt to match any spending in excess of its tax receipts (that is, to match its deficit) with debt-issuance. That is a hangover from the fixed-exchange rate, convertible currency era that collapsed in August 1971.

5. Quantitative easing where the central bank exchanges bank reserves for a government bond – is just a financial asset swap – between the government and non-government sector. The only way it can impact positively on aggregate demand is if the lower interest rates it brings in the maturity range of the bond being bought stimulates private borrowing and spending.

6. But non-government borrowing is a function of aggregate demand itself (and expectations of where demand is heading). When elevated levels of unemployment persist and there are widespread firm failures, borrowers will be scarce, irrespective of lower interest rates.

7. Moreover, bank lending is not constrained by available reserves. QE was based on the false belief that banks would lend if they had more reserves.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit (December 13, 2009) and Building bank reserves is not inflationary (December 13, 2009) – for further discussion.

8. Governments always spend in the same way – by issuing cheques or crediting relevant bank accounts. There is no such thing as spending by ‘printing money’ as opposed to spending ‘by raising tax receipts or issuing debt’. Irrespective of these other operations, spending occurs in the same way every day.

9. A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

10. If the government didn’t issue debt to match their deficit, then like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

11. Taxation does the opposite – commercial bank assets fall and liabilities also fall because deposits are reduced. Further, the payee of the tax has decreased financial assets (bank deposit) and declining net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

12. A central bank can always credit bank accounts on behalf of the treasury department and facilitate government spending. This is the so-called ‘central bank financing’ option in textbooks (that is, ‘helicopter money’). It is a misnomer.

And the point is that all this talk of sovereign debt crises and the central bank running out of firepower is actually raising the probability of a renewed financial crisis emanating from the non-government sector, which is clearly, despite all the myths that have been told, was the source of the GFC.

Household debt at elevated levels in Australia

In recent weeks, there has been more discussion about the elevated levels of household debt in Australia.

Last week (September 10, 2018), the Assistant Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia gave a speech to a business group – The Evolution of Household Sector Risks – where she noted that with low interest rates and lax lending conditions household debt-to-income ratios have risen in many developed nations over the last 3 decades.

Australia is now in the “top quarter of the sample” of developed countries.

She said there were two vulnerabilities as a result:

1. “any difficulties in the residential mortgage market could translate to credit quality issues for banks … the Australian banking system is potentially very exposed to a decline in credit quality of outstanding mortgages.”

2. “if there were an adverse shock to the economy, households could find themselves struggling to meet the repayments on these high levels of debt … If they have little savings, they might need to reduce consumption in order to meet loan repayments or, more extreme, sell their houses or default on their loans.”

Both of these are obvious and get forgotten in the mad rush to borrow.

I considered this issue, in part, in this recent blog post – Reliance on household debt and a lazy corporate sector – a recipe for disaster (September 6, 2018).

That blog post noted that corporate profits are booming, private capital formation is flat, wages growth is flat and consumption expenditure is being driven by a falling saving ratio and rising household debt levels.

The ratio of household debt in Australia to annualised household disposable income is now at record levels – each month a new record is established.

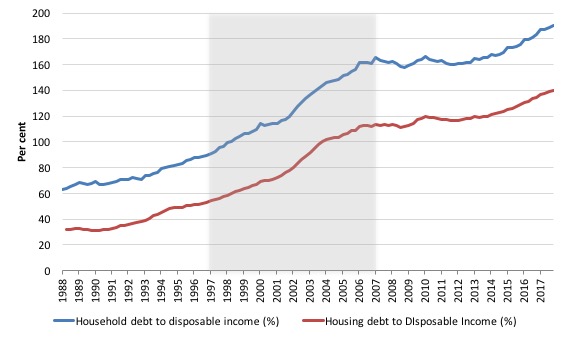

The following graph shows the ratio from 1988 (the beginning of the series) to the March-quarter 2018 (latest).

In June 1988, the ratio was 63.2 per cent. It peaked at 171 per cent in the June-quarter 2007, just before the GFC emerged.

It stabilised for a while as the fear of unemployment and the economic slowdown curbed credit growth for a while. But that didn’t last.

Over the last two years it has accelerated considerably and now stands at 190 per cent. The housing component of that total debt position has also been rising and now stands at 140 per cent of disposable income. At the turn of the century (March-quarter 2000), the ration was 66.8 per cent.

The shaded area denotes the period the federal government ran fiscal surpluses (10 out of 11 years) and during that period the financial sector ran amok with the lack of supervisory oversight, courtesy of the dominant neoliberal ideology.

The position of Australian households, carrying record levels of debt, is made more precarious by the record low wages growth and the conduct of the private banks.

Please read my blog post – Australia’s household debt problem is not new – it is a neo-liberal product – for more discussion on this point.

The problem, now, is that the real estate market is starting to cool, fairly quickly in Australia.

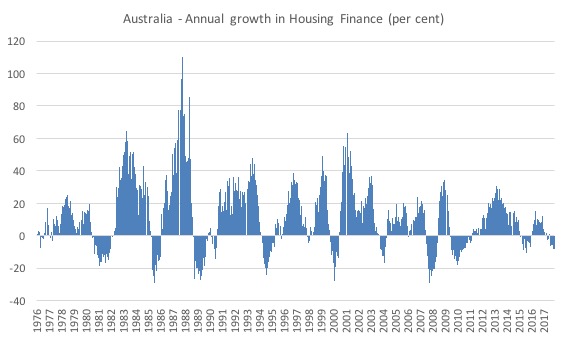

The Australian Bureau of Statistics published the latest data for – Housing Finance, Australia, July 2018 – recently (September 7, 2018), which showed that both owner-occupied financing and investment dwelling financing has fallen away quite sharply in recent months.

Indeed, total housing finance growth (net of refinancing of owner-occupied housing) has been negative in all months bar one since December 2017.

Most of the decline is in the investment dwelling financing as the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority forced tighter lending standards onto financial institutions.

This Press Release (April 26, 2018) – APRA announces plans to remove investor lending benchmark and embed better practices – explains how the regulator sought to tighten lending in the speculative section of the housing market.

It illustrates that governments can modify speculative housing bubbles if they want to.

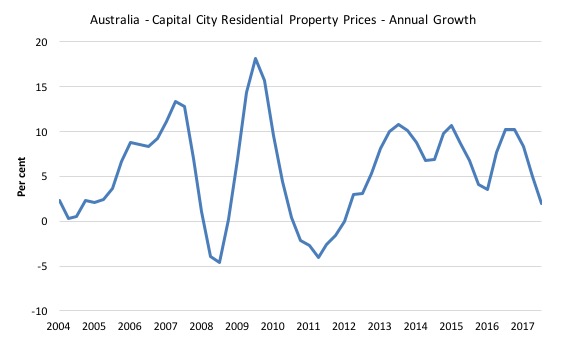

And the next graph indicates why the conversation about household debt is finally ramping up. It shows the annual growth in residential property prices (weighted average of the eight capital cities) from the September-quarter 2004 to the March-quarter 2018.

Housing prices are falling towards zero and it is expected they will cross that line in the June-quarter.

Conclusion

With the recent national accounts data showing the household saving ratio is now down to 1 per cent and heading back to pre-GFC negative territory and flat wages growth, the vulnerability of households to changes in economic conditions is massive.

Add into that the decline in housing prices, which underpin the record levels of debt and you have a recipe for a disaster.

All of this is in the context of a federal government that is projecting a return to fiscal surplus in the not too distant future, which is further squeezing households.

That is the part of this discussion that is lost in the mainstream media.

A government surplus is exactly equal to the non-government deficit.

Taking more out of the expenditure and income generating stream (via taxation) than is being put in (by government spending) forces the non-government sector into a state of liquidity squeeze.

It can maintain expenditure growth for a time by running down saving (as it is) and increasing borrowing (as it is).

But that cannot last, especially as the growth in asset values that have driven the debt start to taper off.

But as long as the financial press doesn’t make the link between what is going in the fiscal space with what is going on with respect to non-government debt and asset prices we will see this dichotomised discussion.

The right-wingers will rave on about public debt and the evils of deficits.

The others will rave on about the dangers of household debt.

Neither will realise or articulate the idea that to provide some security to the non-government sector, it is likely that the government sector will have to run continuous fiscal deficits.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“If there is mass unemployment (higher than frictional – what you would expect as people move between jobs in any week), then the government’s net spending (its deficit is too low or surplus too high).”

Dear Bill, I think this sentence lacks a final descriptor, such as “is insufficient”?

Best, Mr S.

@prof bill – I find your statement – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still! – a bit unsettling. There must be some scenarios where it may not be enough. Are you aware of any?

Dear Larry (at 2018/09/17 at 9:19 pm)

I wouldn’t have made the statement if I knew of any “scenarios” that contradicted it.

best wishes

bill

It appears to me there are “bad actors” out there who will actually welcome another GFC. After all the last time the banks were rewarded and further entrenched their power. Rinse and repeat??

Bill,

In regards to housing, can the government not offer a public bank option that redenominates your debt at land value should housing prices beginning to plummet? It seems like a sensible idea.

You’d then, under a public credit system, offer 0 percent loans on home purchases (tied to loan to income ratios) and disincentive ‘investments’. Tax on rents, capital gains, end negative gearing and a land value tax.

Dear Pr. Mitchell,

What about places with massive housing bubbles and a fixed exchange rate such as Hong Kong? Could they also run continuous fiscal deficits or would they be constrain by the amount of money they could put in circulation?

Best regards,

PJ

Not for the first time, I wish to record my complete agreement with Bill on “fiscal space”: i.e. that the idea is complete BS.

Larry, Re the question as to whether there are any circumstances where more public spending cannot deal with a financial crisis, a possible scenario is this. Suppose governments and central banks had let many more commercial banks collapse during the crisis. In theory, increased spending on infrastructure, health, education could absorb the resulting hoards of unemployed. In practice, the unemployed would have taken time to learn new skills etc, so the change would not have been easy.

But the solution would have been to rely less on public spending and go for tax cuts as a partial alternative. The result would have been that people who normally would have borrowed from banks to fund new house purchases would have found their bank balances swollen. Thus many of them would just have paid cash for their new or larger houses. Construction workers would have kept their jobs.

Back in January, my family and I applied for a car loan for the very first time.

Thing is, the company never asked for a pay stub to verify my pay. My father’s name was on the loan along mine, he hasn’t had a job for decades. Guess the loan is to the banks so they didn’t care.

The car loan application process led me to think about MMT and economics for a bit.

I can totally see that kind of unverified loan happening with a house. I can also see how people can be scammed as first-time home buyers without any family member having “bought” a house before.

I could have lied on my loan application for the car. There was nothing preventing me.

Funny side story: when our previous used car got totaled, we got offered market value for it by the insurance. They offered us 800 USD and said it was market value.

There was/is no way for anyone to buy a used car at the condition we had ours with 800 USD. I don’t think you can get any drivable used car with 800 USD. I should have brought that up to the insurance agent just to see him squirm defending his number.

HSBC laundered drug money. I almost forgot about that.

I can never bring myself to trust these people at my wage level. Anyway, nobody buys house in Los Angeles, so I am just looking at these things to learn about it.

Some smarty-pants people say that the world has changed: Americans need to live at a lower standard of living and save more than before so they can insulate themselves against whatever. I have heard that people say students/young people in their 20s should never eat out and just don’t buy anything.

Then of course you get lower aggregate demand because people aren’t buying things –> bad economy by aggregate.

I am all for working against the consumer culture, but not to the point of eating instant noodles 24/7 in ones’ twenties.

As I grow older, I realize that there are quite a bit of blind leading the blind.

The issue is stagnant wages, parasitic financial sector, and junk economics.

Speaking of blindness, Martin Feldstein is so stupid I won’t trust him peeling an orange with a knife.

Lots of interesting article linked on this piece. I can go through them all today.

Bill, your prison list tweet example is priceless.

Tom, I think they may have been saying that your car was worth $x before it got totaled. That is what it would have been worth had you sold it just before it got totaled. Of course, after it got totaled, it was worth only what a scrap merchant would have paid for it.

I think the problem with the debt problem in Australia, UK, and the US has 3 elements.

1] Banks lend too much to too many people, people who will not be able to pay.

2] Corps. just refuse to increase wages, this makes people want to borrow. They hope they will earn more soon, but they will not until the gov. takes actions to make corps. pay more.

3] Deregulation of banks.

Can anyone help me. On another site I’m saying the fractional reserve banking does NOT constrain banks in any way. That the loans they make create deposits which count toward their reserve requirement. He says the the Prof. MMTers who tell me this “are flat wrong”. What can I say to him to convince him. He seems sometimes to be going on authority [like saying that the US Gov. *can’t* pay interest on the debt with dollars that it borrows, it must pay with dollars from tax revenue.]

.

Prof. MMTers are flat right. We got your authority right here:

https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/conference/1/conf1i.pdf

This is by Alan Holmes, a Senior Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, writing in 1969:

“naive assumption that the banking system

only expands loans after the System (or market factors) have put

reserves in the banking system. In the real world, banks extend

credit, creating deposits in the process, and look for the reserves

later.”

And slightly later:

“In any given statement week, the reserves required to be main-

tained by the banking system are predetermined by the level of

deposits existing two weeks earlier.”

Larry,

Right, my point is that it was worth more than 800 before it got totaled. My father have always donated our worn out used cars over the years to some breast cancer charity.

I don’t think many of them are legit but that’s another story.

That car was hit in the front on the left turn lane before going into an intersection. The van that hit the car was cutting through 2-3 lanes full of vehicles making a left.

Doesn’t insurance suppose to reimburse us so we can buy a car of similar/same quality?

Our car was worth way more than 800 USD. My father and I replaced many things and even had a mechanic replaced some drive strut IIRC.

All I’m saying is that the insurance company’s market price is fictitious: I can’t buy a car of similar quality with 800 USD anywhere.

Where do I err in this analysis? At the beginning of the day, the Federal Reserve has an infinite checkbook and the private sector holds mortgage backed securities that “yield” about 5% that is collected by the private sector. This is probably a neutral event since it is interest paid by the private sector to the private sector. Then the Fed decides to bail out the private sector by issuing (buying) that paper. At the end of the day, the Fed is receiving those interest payments and the private sector loses those interest payments. So, quantitative easing takes interest payments out of the private sector and gives it to the public sector (the Fed sends that money to the Treasury). Similarly when the Fed sells those bonds back to the private sector, they transfer interest payments back to the private sector. Is that tightening?

Tom, I am sorry but I didn’t quite understand the situation. It does look as though the insurance company is fiddling the figures.

Steve_American, have him read J D Alt’s The Millennials’ Money. The first chapter is a set of diagrams. It deals with fundamental issues and should be a reasonable read. The author is an architect. It does deal well with the taxation issue and the banking system.

One of the major difficulties for MMT has nothing to do with the merits of its theoretical basis.

It is the sheer fear of people that throwing money at the problem will unleash terrible consequences.

There is no need even to highlight the potential ideological bias that attaches to MMT – the fear is already plain to see and resides in any householders attitude to monetary proliferation. They can only see a legitimate return where there is equivalent effort, and one is a reward for the other.

As far as the man/woman in the street is concerned the arcane subject of accounting is dominated by books that balance and though they may acknowledge the role of bank lending in generating enterprise he/she believes that the bank loans money already in existence.

For generations people have lived in a capitalist society; forget about the corrupt element contained therein, the ordinary person mainly sees a highly competitive process where only the most advanced and resilient businesses survive and thrive.

The threats that abound appear linked to efficiency, and of interference in the running of organisations or sectors – historically portrayed as wayward politicians whose agenda is more likely to stymie progressive action than promote it, whose (well meaning) social agenda ends up in debt-strewn tatters while the country sinks once again into competitive decline compared with rival economies.

And I haven’t even mentioned the widespread belief that immigration is not only destroying jobs, but also the essence of the country’s culture.

Bill has spoken of taking MMT to the people. Let us have more practicable examples of how it is to work and what are the likely economic and social implications of this.

Hi Steve, thanks for the question. I will try my best:

1. https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=14620 refer to this one =)

Fractional reserve system lending as depicted in mainstream economics just doesn’t exist. Instead, banks make loans to creditworthy customers and look for reserves later (demand deposits, from other banks, or the central bank; they have to pay a rate for all these). banks’ loan departments do not talk with their reserve requirement departments when they make loans. MMTers frequently point out that they are on different floors or different buildings.

Higher reserve requirement can push down the profit margin for bank lending. However, banks will get their reserves cheaply, so practically, they won’t be reserve-constrained when they make loans.

Nobody would design a bank so asinine that it can’t find reserve and it just stops doing stuff. Banks require reserves to settle between banks, so any blockage in that system is just silly.

You can refer to Randy Wray’s primer and see how reserves move from bank to bank on the book’s balance sheet analysis. In my opinion, reserve requirement does not constrain lending unless you go to the realm of the ridiculous and demand that nobody deposit any money in any bank, make a law saying no banks can buy/sell reserves between themselves, banks can’t sell securities to central bank for reserves, and make ridiculously high penalty rate at the central bank etc.

Of course, I think its important to point out bank lend mostly to real estate (80%), corporate raiding, and mergers. Most companies expand with their profits, not bank credit. Banks do not lend for new businesses.

You can just say to that person that the loan department make loans by creating money out of thin air without consulting the reserve management department. They create demand deposit and a liability at the same time. Then after a certain accounting period, the reserve management must make sure the bank has enough reserves to satisfy the requirement. Finally, it is easy for banks to find cheap reserves, so lending is never reserve constrained by all practical purposes. They are limited only by creditworthy customers.

2. “US Gov. *can’t* pay interest on the debt with dollars that it borrows, it must pay with dollars from tax revenue.”

The above assertion is wrong because it states that the US government is constrained in any way by its tax revenue.

The context is probably about how oh we must pay the debt with taxes so higher taxes not to burden our children in the future blah blah.

First, total government debt should never be paid off because I need my dollar bills to buy lunch every day. If they want to lower that debt, tax the wealthy first because they have the money, I don’t have any.

I think that the person was referring to the national debt when he/she was talking about “the debt”. Well, the national debt is sum of all treasury securities. Its just savings with interest. If voters allow it (they won’t), you can just not sell new securities and let the existing ones come due, national debt will go down. If you can’t stand the big number this week, just buy securities with reserves. Now I don’t know if you can force everyone to sell you securities back. FDIC only insures 250,000, so it’s a hard sell I think.

Anyway, Its all scorekeeping, dollars do not go anywhere, they get marked down or up.

By all practical purposes, US government pays interest on the debt with a keyboard on a computer. We are not running out of photons or fingers, so the US government can service any interest on any debt. The US government performs all funding operations the same way with a keyboard on a computer by crediting bank accounts.

Thomas Nugent,

I think you are right on that but I don’t think financial sector has anywhere near as much propensity to spend as the entire economy.

The effect is there, but small.

Thomas E. Nugent, one thing is that if the Fed is buying MBS, they are buying them from a particular segment of the private sector- so they aren’t bailing out the entire ‘private sector’- just possibly that part of it that holds mortgage backed securities. And the extent of the bailout of that segment depends a lot on the nature of the securities. If they were ‘good’ assets and the owners just needed more liquid cash at the time they sold, and they were sold at a reasonable price (whatever that is), then it is not so bad a bailout and might be consistent with most people’s conception of the public purpose. And I guess that the returns they might have earned, that will now be collected by the Fed have a similar effect as taxation would as far as removing money from that sector. But if the MBS were actually junk assets that were sold because they weren’t worth what the Fed was offering then that is a total bailout. And if that is the case we won’t see the Fed selling them back to the private sector at anywhere near the purchase price cause no one would want to buy them. I wonder which is closer to reality.

Thomas E. Nugent, one thing is for sure though- the Federal Reserve never needs mortgage backed securities for any reason whatsoever. Just because of that I am inclined to think they were overpaying for junk and am still bitter about it.

“But if the MBS were actually junk assets that were sold because they weren’t worth what the Fed was offering then that is a total bailout.”

And those that were bailed out took the money and sunk it into Apple and Amazon shares.

Not a bad way to turn a sow’s ear into a purse.

Non economist.

I live in a country with a pegged exchange rate regime with its own central bank. I would want to argue that it depends on the degree of “openness” and the degree to which capital and exchange controls are used. The “domestic” money in circulation,(through continuous deficits) going to expand domestic production would not be the constraint. The constraint remains the scarcity of “real” resources and in this case that would also include available”foreign reserves”.

PhillipO, to say that a country has a pegged exchange rate regime with its own central bank does not make any sense. That’s like saying that it has a pegged rate regime with itself. To have a pegged rate regime, a country has to peg its currency to an entity outside of itself.

I,am not knowledgeable enough to understand the financial situation completely, but it appears to me, that the financial overlords in this world manage a financial crisis every few years, after which more wealth has shifted from bottom to top; yet politicians and economists talk of trickle down effect.

What amazes me, are the many comments in response to this article.

As another interesting question, if a borrower owes, Say $100,000, a creditor is owed the same amount; who, and where are all the creditors.

There is also the ideology of the homeopaths like Greenspan who essentially argued that the markets for derivatives were so efficient this in itself would (somehow) eliminate fraud and provide a mechanism for self-regulation. (as in the way horses grow on trees).

10 years on i cant think of any financial sector that was brought to heel since.

In the field of software security you can either ‘black list’ forbidden functionality. Which always leaves an undocumented subset of future exploits. Or you can ‘white list’ exactly what can be allowed automatically banning all other undocumented functionality.

If there was to be any learning from mistakes regulators would have looked at the financial sector and re-designed it to allow only a white list.

Larry,

Yes, I spotted that after posting the comment… The man did not walk down the road wearing a hat LOL. I should have said:

I live in a country with a pegged exchange rate regime AND its own central bank. or

I live in a country with its own central bank and an exchange rate pegged to the $UD.

Did you get the point though?

PhillipO,

The old “peg it to something so the markets know it’s real” nonsense. How good of an idea that is can be seen with the rise of the dollar last year – ops, a bunch of countries suddenly have a hard time exporting, so it’s time to cut jobs and wages and so on. One of the best perks of the EU, even.

PhilipO, you are describing the Bretton Woods system in the second disjunct and, say, Denmark in the first. Neither is ideal. Better to peg to nothing and accept the character of the fiat system as it is.

Larry

So, you did not get my point….

I get yours though….No problems.

That is all fine and well, but what can a government do in a globalized environment? Sure, if you’re the USA, you can spend all you want with little fear of having a currency crisis. But for smaller countries, who have to finance their import spending with foreign currency, the situation is more complicated. Only a return to controlled capital and trade flows can reconcile the principles of MMT with those of the mainstream on public spending, i.e. by making sure that whatever country the government spends stays inside the country.