Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – December 8-9, 2018 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

An application of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tells us that the current proposals for a Green New Deal in the US and elsewhere will lead to crowding out of other investment.

The answer is True.

The current proposals for a Green New Deal will have significant implications for resource usage in the nations that pursue that policy framework.

In the US, there are estimates that these initiatives might absorb up to 14 per cent of the labour force.

At a time when unemployment is historically low, a shift of this magnitude will clearly require a squeeze being put on other sectors.

But this will be a real resource squeeze mediated through taxation and regulation.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis, which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called financial crowding out.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory. Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

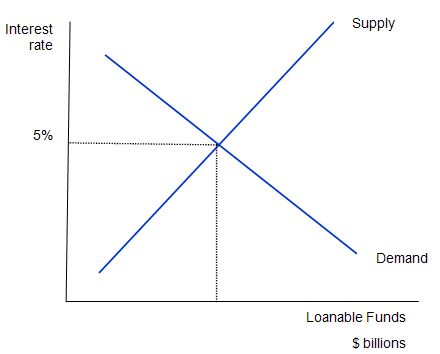

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds.

The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate).

The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out.

The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc).

The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate.

This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment.

Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that fiscal surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector).

They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of fiscal surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure.

The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consequences of fiscal deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a fiscal deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

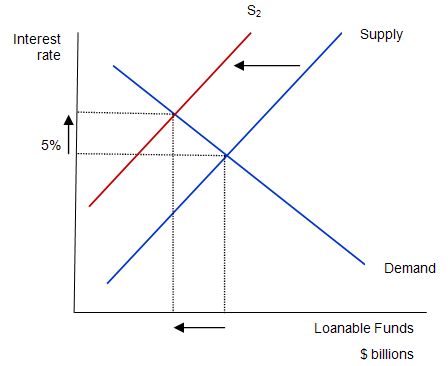

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2.

Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising fiscal deficit reduces public saving and available national saving.

The fiscal deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”.

Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it.

Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length.

This trilogy of blog posts will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no!

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible.

There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors.

Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on.

Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans.

The result competition for the ‘finite’ saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading ‘financial crowding out’.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible.

In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government fiscal capacity all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise fiscal surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios.

So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues.

If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example).

But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 2:

A rising government deficit will always allow the private domestic sector to increase its saving in nominal terms.

The answer is False.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

Relating this knowledge to the question, we know that if the external balance is zero (that is, net exports equal zero) the there is a one-to-one correspondence between the government balance and the private domestic sector balance such that, for example, a 2 per cent fiscal deficit must be associated with a 2 per cent private domestic sector balance surplus.

So in this circumstance the answer would be true.

But things get complicated when we introduce positive or negative external balances. Then, for example, a 2 per cent fiscal deficit that was associated with a 3 per cent external deficit would leave the private domestic sector balance in deficit.

So the answer is only true if the fiscal deficit is larger (as a percent of GDP) than the external balance and growing faster.

Question 3:

A lack of a close correspondence between the growth of bank reserves and the growth in the stock of money is evidence that credit creation is being tightly constrained.

The answer is True.

It has been demonstrated beyond doubt that there is no unique relationship of the sort characterised by the erroneous money multiplier model in mainstream economics textbooks between bank reserves and the “stock of money”.

You will note that in MMT there is very little spoken about the money supply. In an endogenous money world there is very little meaning in the aggregate.

Central banks do still publish data on various measures of “money”. The RBA, for example, provides data for:

- Currency – Private non-bank sector’s holdings of notes and coins.

- Current deposits with banks (which exclude Australian and State Government and inter-bank deposits).

- The M1 measure – Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector.

- The M3 measure – M1 plus all other ADI deposits of the private non-ADI sector. So a broader measure than M1.

- Broad money – M3 plus non-deposit borrowings from the private sector by AFIs, less the holdings of currency and bank deposits by RFCs and cash management trusts.

- Money base – Holdings of notes and coins by the private sector, plus deposits of banks with the Reserve Bank and other Reserve Bank liabilities to the private non-bank sector.

Note that ADI are Australian deposit-taking institutions; AFI are Australian financial intermediaries; and the RFCs are Registered Financial Corporations. Here is the RBA’s excellent glossary for future reference.

The mainstream theory of money and monetary policy asserts that the money supply (volume) is determined exogenously by the central bank.

That is, they have the capacity to set this volume independent of the market. The monetarist portfolio approach claims that the money supply will reflect the central bank injection of high-powered (base) money and the preferences of private agents to hold that money. This is the so-called money multiplier.

So the central bank is alleged to exploit this multiplier (based on private portfolio preferences for cash and the reserve ratio of banks) and manipulate its control over base money to control the money supply.

To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in MMT. When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

The essential idea is that the ‘money supply’ is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply. As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans.

The central bank can determine the price of ‘money’ by setting the interest rate on bank reserves.

Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blog posts – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

So a rising ratio of bank reserves to some measure like M3 is consistent with the view that credit creation is being constrained by some factor – such as a recession.

You might like to read these blog posts for further information:

- Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again

- Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained

- Oh no … Bernanke is loose and those greenbacks are everywhere

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- 100-percent reserve banking and state banks

- Money multiplier and other myths

So if I’ve understood Bill’s description aright, then according to Mankiw, there are never any recessions, and it would be normal for a consumption-goods company board meeting to have the following implausible conversation:

“Consumer spending is down, and people are buying fewer of our party hats!”

“Yes, we must shut down one of our production lines and make its workers redundant, just like most other consumption-goods companies are doing.”

“And while it’s shut down, let’s borrow some money to upgrade it.”

“Good idea: interest rates are low at present, because people are putting their incomes into investing instead of partying.”

Then (according to Mankiw) those workers find jobs at a company that makes machinery (“capital goods”) used in party-hat production-lines.

So, when consumption falls, these economists think it’s typical for companies to respond to their falling revenues by borrowing to invest in increased capacity/efficiency? Oh dear…

I should have spotted the real crowding out issue in question 1.

I interpreted “being tightly constrained” in question 3 to mean someone was actively regulating credit creation whereas it could be stagnant because of low demand.so I though it could be false because low money supply growth could be due to lack of willing creditors not regulation on credit.

N that narrative about investment never fails to shock me as does the Ricardian equivalence one that if people lose their governments jobs they are going to go on a spending spree- expansionary fiscal contraction. So implausible that you’d laugh if you weren’t crying.

So, question #1 would be false in an economy with sufficient undercapacity, that is an economy where the demand for goods and services was sufficiently below the ability of the economy to produce goods and services.

On question 1: some commentators have argued that italy’s recent announcement of a higher than expected budget deficit constitutes a case of “crowding out” because this had the effect of increasing the general level of interest rates in Italy (via the government bond market) and thus will be a drag on growth. Although this effect is due to badly conceived EU rules, do you think that the drag on growth will be real ? It seems that EU rules were designed to have this dynamic.

@Remj

I would have a good look at the two part blog on this site about the whole “Italy’s proposed deficit will crowd out private investment via interest rates argument”.

Part 1 is here https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=40964

@ N:

“… then according to Mankiw, there are never any recessions, …”

Bill has talked about this in older posts. That is exactly the thinking that was behind the proclamation of the “great moderation” by mainstream economists before the GFC. As Cs pointed out, most of the thinking in neoliberal economics is just slightly more sad that it is risible.

@ Cs

The part that gets me the most is the non-existance of voluntary unemployment in the neoliberal mindset, and paticularly, in their “tool-of-all-tools”: the DSGE model. To them, the fact some unemployed and their families suffer through hunger and humilliation is a result of their personal optimum between leisure and work. This never fails to bring the words of my namesake, Herman Melville, to my mind:

“Of all the preposterous assumptions of humanity over humanity, nothing exceeds most of the criticisms made on the habits of the poor by the well-housed, well- warmed, and well-fed.”

Using the words of Warren Mosler, albeit in a different context, the Ricardian fallacy is an “innocent fraud” in comparison to this callous conviction.

Regarding deficit spending, I just read about the new pentagon budget and was reminded of the dupliciousness in regards to government spending in the conservative world and, particularly, amongst otherwise “deficit hawks”.

The military is one of the if not the main employer(s) of low skilled workers, particularly form rural areas. In fact, according to some sites, it is the biggest employer of the world. It certainly is the reason many families still vote Republican. The irony of voting for the public-sector-busting party while on the government budget (in the department with the highest funding and constant scandals of wastefulness!) seems lost on them. I would be very interested in any research in this direction, but my gut tells me, that the military might be the biggest, if not necessarily most efficient, anti-poverty programm in the USA. It’s sad that it is designated to use the precarious situation of those impoverished by the system to impose the will of modern day imperialists around the world. Nevermind the fact that most people would probably prefer a similar but less hazardous program. I don’t see how one could argue against the JG and in favor of the current military budget without ending with a gordian knot in his head.

In my opinion, the different treatment of military spending is an implicit concession of the ability of the government to “get things done” in matters of importance (although even in some military matters there is a push for privatization, e.g. Blackwater mercenaries).

where it says ‘CAD’ it is a bit confusing as i immediately assumed it meant current account Deficit , and so was put off by the sign of it in the equation.

later i saw you meant current account Balance – so why the D !