In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Australian government fiscal outlook – irresponsible and will fail

Australia has been caught up in a almost national hysteria the last few days as the Federal government’s Mid-Year Economics and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) release approached. The MYEFO was released yesterday (December 15, 2015) and the sky is still firmly above us, albeit slightly overcast today with storms approaching. I can assure everyone the storms are meteorological events associated with the early summer rather than any moves by international credit rating agencies to detonate their heavy artillery and sink the continent into the Pacific and Indian oceans. The mainstream media coverage of the buildup to the MYEFO has been nothing short of extraordinary and demonstrates that no matter how wealthy a nation’s per capita, how educated it’s people appear to be, public debate is conducted at levels of ignorance that the cavemen and women would laugh at. I have spoken to several journalists in the last few days who by their questioning expose a basic lack of understanding of the macroeconomic implications of the data that has been released in the MYEFO. Basically, the Outlook shows that the federal fiscal deficit is larger than previously estimated (in the May 2015 Fiscal Statement aka ‘The Budget’) and this demonstrates the automatic stabilisers in operation to put a floor under the slowing economy. This counter-cyclical movement is something that we should be comforted by because as private spending contracts and the economy slows the expansion of the deficit limits, to some extent, the job losses and the number of businesses that might become insolvent. However, the mainstream reaction has been hysterical (as in hysteria) with all sorts of predictions about national insolvency, credit rating agencies downgrading us, and “deficits for as long as you can see”. The problem is that the so-called average Australian believes all this nonsense and doesn’t understand that the rising deficit is a good thing in the context of poor developments in private spending.

There was a news story in the Monday edition of The Australian newspaper (a Murdoch rag), which was in anticipation of yesterday’s fiscal statement by the federal government.

In part it said:

Global ratings agencies are calling for tight controls on spending in the mid-year budget update amid independent forecasts of a $33 billion blowout in federal deficits over the coming four years despite the Coalitions election promise to improve the nation’s finances …

Financial markets do not expect the resulting blowout in public debt to trigger an automatic review of Australia’s AAA credit rating, but the government will need to outline a strategy on savings the goes beyond offsetting any new spending with cuts.

Analysts are pointing to comments from ratings agency Standard & Poor’s that Australia’s standings would be in jeopardy if combined net debt of the commonwealth and state exceeded 30 per cent of GDP, or a little over $500bn. The analysts say the deterioration in the budget outlook has not been enough to lift debt to that level.

There was then a parade of quotes from private sector bank type economists which reinforced the message that News Limited wanted the Australian public to receive.

Quotes such as it is “difficult to access just what impact another downgrade of the official budget forecasts might have on the sentiment of rating agencies.”

A journalist rang me yesterday in relation to this issue and began by suggesting that Australia’s AAA credit rating might be in danger and what did I think the implications of that were.

The answer was fairly simple: NONE.

As in – what the rating agencies do in relation to Australian government debt is irrelevant and they should be ignored. Wheeling out the rating agency threat is just another arrow in the neo-liberal quill that is designed to disabuse the public of government spending that might advance the well-being of the disadvantaged.

They never mentioned the rating agencies when the banks are being bailed out or some industrialist is putting his hand out for cash to help his struggling business which is over indebted and facing collapsing foreign revenue. Then it seems that government spending is in the national interest.

A career of reading this junk leads me to wish I’d become an anthropologist or something else like that.

Let’s briefly remind ourselves of some history. I discussed the issue some years ago in this blog – Please note: there is no sovereign debt risk in Japan!.

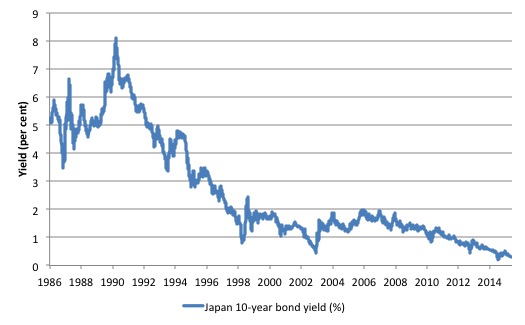

First, here is the history of the Japanese 10-year bond yield since it was first issued on July 5, 1986 to November 30, 2015 (the latest observations in the historical data set). The daily data (all 10,664 observations) is available from the – Ministry of Finance).

Second, what impact has the ratings agencies had on that evolution? Answer: none.

In November 1998, the day after the Japanese Government announced a large-scale fiscal stimulus to its ailing economy, Moody’s made the first of a series of downgrades of the Japanese Government’s yen-denominated bonds, by taking the Aaa rating away.

By December 2001, they further downgraded Japanese sovereign debt to Aa3 from Aa2. Then on May 31, 2002, they cut Japan’s long-term credit rating by a further two grades to A2, or below that given to Botswana, Chile and Hungary.

In a statement at the time, Moody’s said that its decision “reflects the conclusion that the Japanese government’s current and anticipated economic policies will be insufficient to prevent continued deterioration in Japan’s domestic debt position … Japan’s general government indebtedness, however measured, will approach levels unprecedented in the postwar era in the developed world, and as such Japan will be entering ‘uncharted territory’.”

If you examine the graph you won’t see much happening around 2002 other than falling yields on 10 year bonds.

The Japanese government (Finance Minister) responded very sensibly: “They’re doing it for business. Just because they do such things we won’t change our policies … The market doesn’t seem to be paying attention.”

Indeed, the Government continued to have no problems finding buyers for their debt, which is all yen-denominated and sold mainly to domestic investors.

There have been several similar downgrades since then by the three major credit rating agencies, all of which have been accompanied by statements like “The government lacks a ‘coherent strategy’ to address the nation’s debt” – and none of which

have disturbed the yields on the bonds.

At some point, humanity is going to work out that this is one of the greatest scams of all time. The rating agencies are irrelevant when it comes to sovereign debt for nations that issue their own currency and do not borrow in foreign currencies.

I thought the conclusion in this Bloomberg article (September 16, 2015) – Oh, No! Japan Gets Downgraded. Oh, Wait.which followed the most recent Standard & Poor’s downgrade for Japan was rather apposite:

So the Japanese sovereign downgrade isn’t a meaningful development. Best to ignore it, as markets undoubtedly will.

The Japanese government never had any trouble finding buyers for the debt it was issuing, they held complete control over interest rates, inflation fell, unemployment remained relatively stable and real GDP growth was strong through the period of the downgrade.

The decision by Moody’s in 1998 was rendered irrelevant by the Japanese government (as were all subsequent decisions) who just exercised the power they had as a sovereign issuer of the currency.

I could show you the US ten-year bond yield evolution in recent years after the rating agencies downgraded their debt and the same conclusion would be drawn. No rating agency impact.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

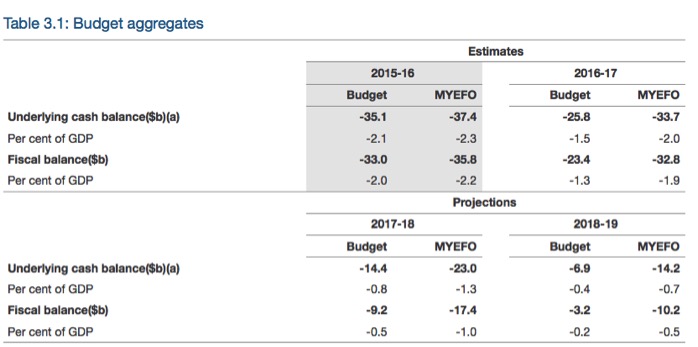

The following table (taken from Part 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook section of the MYEFO) and summarises the fiscal aggregates out to 2018-19.

The first column in each year is the estimates or projections in the May fiscal statement and the second column is the updated estimates from Treasury presented yesterday.

All sorts of permutations of cumulative increases in the deficit are possible – the mainstream media has sensationalised them using terms like “blow out”, “the gaping hole”, and similar – but all that we need to know is that in the May 2015 Fiscal Statement, the Treasury overestimated the taxation revenue that the federal government would receive and as a result underestimated the fiscal outcome for that financial year.

Please read my blog – Australian fiscal statement 2015-16 – cynical and venal – for more discussion on this point.

As I explained in that blog, which covered the release of the ‘Budget’ in May 2015, the Treasury forecasts of real GDP growth in the next several years were ridiculously inflated, for reasons only they can explain.

Even the mainstream press were unimpressed with the real GDP forecasts. Clearly, those forecasts were necessary to generate the cyclical growth in tax revenue that for political reasons the government required in order to claim that they would be back in surplus by 2019-20.

After all, the current Australian government had come to office on the back of a massive scare campaign about the so-called “fiscal emergency” and their claims that they would return to surplus almost immediately.

This was always a basic lie given the underlying spending and saving decisions by the non-government sector. Commodity prices were falling in international markets and significantly constraining export revenue. The investment boom that had accompanied the record commodity prices had come to an end and firms were not redirecting investment into the non-mining sector.

The household sector already massively indebted from the credit bingeF prior to the GFC were showing a desire to save at least 9 or 10 per cent of their disposable income, which meant that consumption would not make up for the lost investment spending.

That reality soon dawned on the new Conservative government and by their second year they had conveniently shelved all their blow-hard rhetoric about fiscal emergencies as they realised that the economy was slowing down rather quickly and the labour market was deteriorating under their watch.

They were at that stage facing the prospect of being a one-term government, which is a rare feat that only the most incompetent federal regimes achieve.

Their electoral plunge was all the more profound given the pathetic state of the main opposition – the Labor Party.

So, in the May Fiscal Statement, we learned that there was no fiscal emergency and that on-going deficits and rising public debt are okay. But to assuage the extreme right wing elements of the party they had to also continue the myth that they were going to achieve a surplus in the relatively near future.

As a result, they had to introduce ‘budget’ forecasts which would demonstrate that a surplus was in the offing in the not too distant future. Hence, the ridiculously optimistic real GDP forecasts.

The problem for the Australian people was that their conservative DNA is such that they refused to take the next step (after realising their ambitions for austerity would have to wait a while) and acknowledge that spending equals income and that the slowdown in real GDP growth was the result of insufficient spending.

So in May 2015, we received a fiscal strategy that did not impose as much austerity and inequality as their DNA would desire but also failed to meet the major challenges facing the nation – the increasing labour underutilisation rates, flat real wages, flat economic growth.

It provided no path to addressing these things within the realities that climate change and natural resource frailty impose.

And with non-government spending continuing to ease, real GDP growth fell well below any of the official estimates. As a result, federal taxation receipts have fallen well below expectation.

As a result, the fiscal deficit has risen as it should when private spending falls and labour markets slack increases.

The ridiculous forecasts continue

The following graph is Part 2: Economic Outlook of the MYEFO and shows actual real GDP growth (annual) from 1988-89 through to 2018-19. That jump in 2011-12 was directly the result of the large fiscal stimulus that the federal government introduced in late 2008 and early 2009.

As you can see, the Treasury is forecasting the gross will be as strong or stronger in the next four financial years as it was in the previous seven (ignoring the year that benefited from the fiscal stimulus).

This is in an environment where private investment spending is forecast to contract significantly, growth in household consumption spending is likely to be relatively modest, the current account deficit (the external drain on spending) is forecast to remain above 5 per cent of GDP and the government is pursuing a moderately contractionary fiscal stance.

It is hard to imagine where this gross dividend will come from and as a result the fiscal estimates will once again err on the conservative side.

Higher discretionary fiscal deficit is required

While my earlier comments indicate that the rising deficit is a good thing, in that, the automatic stabilisers are doing their job to partially protect the economy from the slowdown in private spending, that doesn’t mean that the fiscal strategy employed by the government at present is responsible.

Indeed, the government is in a sort of weird halfway house. It had enough nous to realise that it’s austerity ambitions in the first year it was in office (2014-15) were likely to significantly derail the economy as the full impact of the private sector spending slowdown was becoming apparent.

In that sense, they are reprising George Osborne’s realisation in 2012 that his ideological obsession with austerity was driving the British economy back into recession. That realisation led to him adopting a more pragmatic approach in that he allowed the fiscal deficit to increase. The British economy has grown as a result of that pragmatism.

But even given that pragmatism, the government is incapable of taking the next, appropriate step which is to expand the discretionary component of fiscal policy (that is, expand spending and/or reduce taxes) to make up for the slowdown in private spending growth and the contraction overall in investment spending.

With the current account deficit forecast to be at least 5 per cent of GDP over the next two financial years and private investment to be contracting, a tighter fiscal strategy will rely on increased household debt to drive the higher consumption spending growth.

The household sector is likely to resist expanding its debt exposure sufficiently to compensate for the moderation or contraction in the other expenditure components.

It would be a much better strategy for the government to show leadership and drive higher growth through increased uptake deficits.

The projected deficit of -1.9 per cent of GDP in 2016-17 could easily be twice that. At present, real GDP growth is struggling to reach 2 to 2.25 per cent per annum even though the government’s own data shows the 20-year average is 3.24 per cent per annum.

There is plenty of scope for increased discretionary net public spending in Australia at present.

In the government’s so-called fiscal strategy which they subtitle in Part 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook section of the MYEFO as “The budget repair strategy” we read that:

The fiscal strategy explicitly recognises that the current fiscal position is in need of repair. As such, the impact of all policy decisions taken since the 2015‑16 Budget (including the cost of Senate negotiations) has been offset …

In other words, the government plans to redirect some public spending into its so-called “National Innovation and Science Agenda” strategy but reduce spending elsewhere so that it “will reduce the Government’s share of the economy over time in order to free up resources for private investment to drive jobs and economic growth”.

First, cars sometimes need repairing because they break down. A ‘budget’ balance is not something that a government should directly be concerned about in isolation to what is happening in the real economy. It makes no sense to think of the fiscal balance as being sick or broken. The analogy fails.

It would be much better for the government to acknowledge that what is in need of attention at present is the weak labour market and the declining investment spending (both private and public).

Second, with nearly 15 per cent of available labour resources idle at present (either jobless or underemployed), it makes no sense for a government to claim that it needs to “free up resources” to allow the private sector more scope to expand.

It’s quite clear that the private sector is currently not intending to utilise those idle labour resources. The problem is that there is insufficient spending to stimulate sales, which, in turn, generates firm demand for labour.

Proudly stating that the strategy is to maintain fiscal contraction when the main problem is insufficient spending is crazy.

What we learned a long time ago (during the Great Depression) is that private sector sentiment does not improve when spending is in contraction. The economy can wallow in a steady-state with high unemployment because firms have sufficient capital capacity to meet the current sales volumes.

In those situations, an increase in public deficit spending provides the circuit breaker to restore private sector confidence.

Third, the government, true to form, is preparing to hand out further largesse to the corporate sector in the form of so-called “innovation” funding and is offsetting that increase spending by greater cuts to welfare spending.

In other words, the forward-looking fiscal strategy is to further punish the most disadvantaged citizens in our society and handover further public funds to capital.

Conclusion

I had an interesting meeting today with my current co-author on a book we are writing about the demise of the Left and the narrative that claims that states are impotent in the face of trends in global financial capitalism. Our contention is that the state has never gone away – all that has happened is that it’s redirected its capacity to benefit capital and disadvantage labour.

The current position of the Australian government is consistent with that hypothesis.

I will have more to say on this topic in the coming months. We plan to release the book later in 2016. A book homepage will emerge in the early New Year.

That is enough for today!

Hysteria seems to be “carrying the day” as the last Republican debate of the year took place tonight in the USA. We were treated ad nauseum to the worst kind of jingoistic Islamophobia and militaristic calls for action against Syria, Iran, ISIS/ISIL and even Russia. Anti-intellectualism and the worst kind of crack pot populism was broadcast directly into the minds of frustrated and stressed out Americans by CNN. It was pathetic. Economics and politics is poor theater. Progressives had better wake up and realize that intellectualism doesn’t have a chance against fear, stress and anger….at least not with the majority. Trump is tapping into the same mentality that Mussolini and Hitler tapped into. It’s a winning formula. The only way to head off an onslaught of such lemming like suicidal idiocy is an economics of jubilee followed by an adequate amount of cold hard cash, paper or digital, in the eager hands of the individual. It’s a race between monetary grace the free gift and a repeat of the worst of the twentieth century.

Lets see, politicians that spin the bull-dust about their precious but non-achievable (and non essential) surplus.

Gillard / Swan gone.

Abbott / Hockey gone.

Turnbull / Morrison about to to be gone.

They hang from their own rope.

Bill, I have realised, I think accurately, that the deficit spend’s limit is the Output Gap, rather than runaway inflation, [also the output gap limit].

Since our economy is in virtual deflation, – any thing under 2% growth approx.- the output gap to a fully charged economy with full employment etc, is going to be a large sum, a very large sum.

So the neocon liberals, emphasis on con, have only bluster to cover their bare arsed lies and confusion.

While Osborne does adjust his cuts according to the GDP figures, this does not mean that he doesn’t cut. He still does this, mainly to the poor and the disabled along with tax advantages for the rich. There is also less money for councils whose income generating ability is capped so that they find it difficult to meet their constituents’ needs. What this means is that overall he isn’t inexorably suppressing GDP, which is going to the top income bracket anyway. It is not being evenly distributed.

A GDP figure by itself in current circumstances is almost meaningless, as you don’t know where the benefits are being felt. You can gain weight in either of two ways – by putting on fat or putting on muscle. The first is unhealthy while the second is what your doctor would order. So, just to say that someone has gained weight is not telling you enough. In a similar way, unequal distribution is unhealthy for the economy as a whole and for the society, however healthy it might be, temporarily, for certain sectors of the system.

Bill,

Until everyone stops carelessly using the same word – “deficit” – across so many contexts undefined to the discussants, coherent conversation is not possible.

At the start of EVERY conversation with a journalist (or any citizen, for that matter), I suggest demanding that they “define their terms.”

If not, expect continued mismatch between what’s said and what’s understood.

We’ve just got rid of one Treasurer clown. Shunted off to a sinecure in Washington DC. I do hope we have some really competent diplomats there (who can tolerate cigar smoke) otherwise we will be seeing crises in Australia – USA relations.

We now have another Treasurer clown. Seemingly there is an inexhaustible supply.Pity there is no market for them.

But the problem is much more deep seated than individual or even collective clowns,unfortunately.

Dear Bill or someone else

Japan and the USA are the two examples always used to prove the point being made in this article

However, their examples may not be applicable to Australia.

Japan has a large current account surplus

USA by its military and political status can always run large current account deficits as there will always be a demand for USD denominated assets (eg oil)

Australia has neither of these things

Is Australia more similar to Russia or the Ukraine? Both of whom were forced to raise interest rates in order to stem a currency collapse?

If not, why not?

Why are those nations susceptible to “bond vigilantes” and we are not? Why are they not autonomously setting their interest rates while we can?

Serious question, I would like to understand

Thank you

Giulio

A current account surplus or a strong demand from foreign buyers for financial assets in the domestic currency are not required in order to run deficits. The sectoral balance equation will show that balance of trade in the external sector (surplus/deficit) will impact the government sector’s position, because all sectors must balance out. But without knowing the private domestic sector’s position, we cannot say whether a surplus or a deficit is a definite.

In Russia’s case, their export market was overly reliant upon oil. When the price fell dramatically, that created a trade imbalance. A floating exchange rate will adjust to reflect this, in this case by the currency depreciating.

Australia has undergone a similar situation whereby our mineral resources (a significant export for our country) have declined dramatically in price. Subsequently, the Australian dollar has dropped from the highs of parity with the USD, to sitting at around 71 US cents today.

This obviously has an impact on the price of imports, which become much more expensive. This can invigorate local manufacturing and make exports more competitive, which is part of the strength of a floating exchange rate. However this obviously takes some time to flow through the economy, and a volatile exchange rate can play havoc on the economy in the meantime. Finally, it also means that the trade imbalance will to a certain extent return to a kind of equilibrium, because as the value of goods changes, so does the volume.

Russia was not “forced” to raise interest rates, however. It was a decision to do so, in an attempt to arrest the devaluation of the currency. Australia, conversely, welcomed the devaluation of its own currency in order to transition from the mining boom. The Reserve Bank at the time was actually struggling with the decision to _reduce_ interest rates, in order to prevent the currency from rising too high, but had to tackle the impact that low interest rates may have on real estate speculation. Quite a different situation indeed!

All of this just goes to show that interest rates are a blunt instrument, and not necessarily the best tool for addressing imbalances in just one area of the economy. I’d let more learned folks speculate on how Russia could have otherwise addressed the issue of their currency.

Michael Lewis in his book the “Big Short” about the wall street CDO’s and Credit Default Swaps, described Standard & Poors and Moodys as employing a bunch of tossers who collectively had no idea what they were doing. Lewis describes the ratings agencies as well below par, which is why they gave AAA ratings for the bundled up mortgage bonds for subprime loans. Wall street ran rings around them, so how can those agencies be treated seriously?