With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Takahashi Korekiyo was before Keynes and saved Japan from the Great Depression

This blog is really a two-part blog which is a follow up on previous blogs I have written about Overt Monetary Financing (OMF). The former head of the British Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner has just released a new paper – The Case for Monetary Finance – An Essentially Political Issue – which he presented at the 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, hosted by the IMF in Washington on November 5-6, 2015. The paper advocated OMF but in a form that I find unacceptable. I will write about that tomorrow (which will be Part 2, although the two parts are not necessarily linked). I note that the American journalist John Cassidy writes about Turner in his latest New Yorker article (November 23, 2015 issue) – Printing Money. Just the title tells you he doesn’t appreciate the nuances of central bank operations. He also invokes the Zimbabwe-Weimar Republic hoax, which tells you that he isn’t just ignorant of the details but also part of the neo-liberal scare squad that haven’t learnt that all spending carries an inflation risk – public or private – no matter what monetary operations migh be associated with it. I will talk about that tomorrow. Today, though, as background, I will report some research I have been doing on Japanese economic policy in the period before the Second World War. It is quite instructive and bears on how we think about OMF. That is the topic for today.

Takahashi Korekiyo – was the 20th Prime Minister of Japan and held office twice the last time in an acting capacity in 1932. He had previously worked in the Bank of Japan. For the most part though, he was Finance Minister under various administrations from the late 1920s until his death in 1936.

I have been researching documents in the Bank of Japan archives for some time now as part of a book project I am working on. I am up to the period that Takahashi Korekiyo was a major player in Japanese economic policy making and it just happens to fit in with the comments I wish to make about Adair Turner and John Cassidy.

But I thought this background would help us for tomorrow.

Takahashi Korekiyo is famous for abandoning the Gold Standard on December 13, 1931 and introducing a major fiscal stimulus with central bank credit which rescued Japan from the Great Depression in the 1930s. That is quite a reputation. His actions and the subsquent results provide a solid evidence base for assessing whether OMF is desirable.

I note that OMF is core Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) policy, a point that Cassidy seems to be worried about. More about that tomorrow.

As to Takahashi Korekiyo, I don’t think his monetary acumen had anything to do with his assassination (in his sleep by gunshot and sword) by rebel army officers in 1936 during the so-called – February 26 Incident – which was a failed coup d’état.

He had in fact reduced military funding because he was a moderate and wished to reduce Japan’s martial tendencies. Enemies were thus made and they were the type of enemies that carried weapons and knew how to use them!

As background, Japan had experienced a major private banking collapse in 1927 (the Showa Financial Crisis) as a result of what has been referred to as “cumulative mismanagement of cover-ups and halfway measures against earlier flaws dating back to the post-war collapse” (quote from Takahashi, Kamekichi [1955a], Taisho Showa Zaikai Hendou Shi (A History of Economic Fluctuations during Taisho and Showa Eras), vol.2, Toyo Keizai Shinposha, Tokyo, p.739).

In other words, the banksters were out in force in Japan during the 1920s. It is argued by Takahashi Kamekichi that the stimulus measures introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo were assisted by the reforms that were made in the late 1920s to deal with the Showa Financial Crisis.

There were three notable sources of stimulus introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo:

1. The exchange rate was devalued by 60 per cent against the US dollar and 44 per cent against the British pound after Japan came off the Gold Standard in December 1931. The devaluation occurred between December 1931 and November 1932. The Bank of Japan then stabilised the parity after April 1933.

2. He introduced an enlarged fiscal stimulus. In March 1932, Takahashi suggested a policy where the Bank of Japan would underwrite the government bonds (that is, credit relevant bank accounts to facilitate government spending).

This proposal was passed by the Diet on June 18, 1932. The Diet passed the government’s fiscal policy strategy for the next 12 months with a rising fiscal deficit 100 per cent funded by credit from the Bank of Japan.

Bank of Japan historian Masato Shizume wrote in his Bank of Japan Review article (May 2009) – The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Ipact of the World Depression – that:

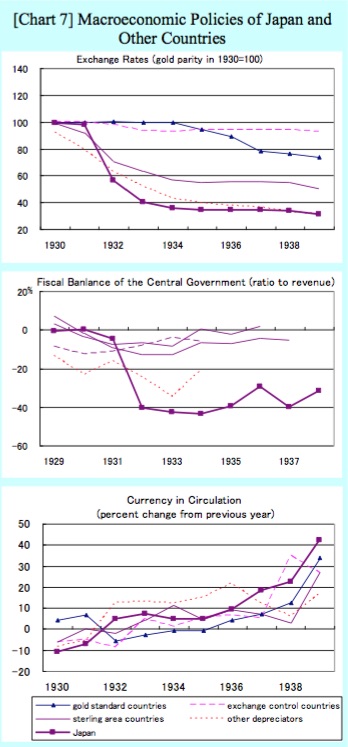

Japan recorded much larger fiscal deficits than the other countries throughout Takahashi’s term as Finance Minister in the 1930s.

On November 25, 1932, the Bank of Japan started ‘underwriting’ the government’s spending.

3. The Bank of Japan eased interest rates several times in 1932 (March, June and August) and again in early 1933. This easing followed the cuts by the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank in the US. Monetary policy cuts were thus common to each but the size of the fiscal policy stimulus was unique to Japan.

Masato Shizume wrote that:

A number of observers who focus on the macroeconomic aspects of the Takahashi economic policy praise Takahashi’s achievements as a successful pioneer of Keynesian economics. Kindleberger points out that Takahashi conducted quintessential Keynesian policies, stating, “his writing of the period showed that he already understood the mechanism of the Keynesian multiplier, without any indication of contact with the R. F. Kahn 1931 Economic Journal article.”

[The full reference is: Shizume, Masato (2009) “The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Impact of the World Depression”, Bank of Japan Review, 2009-E-2]

The next graph is a reproduction of Chart 7 Macroeconomic Policies of Japan and Other Countries from Masato Shizume’s paper. It is self-explanatory.

The big variation between the different currency blocs and Japan is in fiscal policy.

There is substantial discussion in the literature about the relative impacts of these three different stimulus measures. But what followed is clear:

1. Real GDP growth returned quickly and stood out by comparison with the rest of the world which was mired in recession. Between 1932 and 1936, real industrial production grew by a staggering 62 per cent.

2. Employment, which had also plummeted in the early days of the Great Depression, grew robustly after the Takahashi intervention.

3. Inflation spiked as a result of the exchange rate depreciation in 1933 but quickly fell to low and relatively stable levels in 1934 as the economy’s growth rate picked up under the support of the fiscal and monetary stimulus.

It was clear that abandoning the Gold Standard was a crucial first step because it gave the government space to introduce major domestic stimulus policies. These policies were not possible under the Gold Standard because they would have pushed out the external deficit and the nation would have lost its gold stocks.

I note a number of the current Republican presidential potentials in the US are once again calling for a return to the Gold Standard. They clearly haven’t a clue what they are talking about given the appalling record of nations when they were on such exchange rate mechanisms.

It was the Gold Standard that ensured the Great Depression ensued. As the US started to run trade surpluses in 1929 (after the recession choked off imports), other nations started to deplete their gold stocks which meant they had to raise interest rates to attract capital inflow. The US recession spread and many investors in Europe considered that the central banks would have to devalue. Anticipating that, they withdrew gold and the contractionary effects on the money supply worsened the downturn. Then banks collapsed and so on.

There is an interesting article (November 12, 2015) by Greg Ip – What Republicans Get Wrong About the Gold Standard – that bears on this issue. It is targetted at those stupid Republican candidates.

Clearly, Takahashi Korekiyo understood the constraints that the Gold Standard and the need to maintain the money supply in proportion with the nation’s stock of gold imposed on domestic policy. Once he removed that constraint he could then use the fiscal and monetary tools available to him (and through the Bank of Japan) to target domestic demand.

Some researchers have suggested that the combination of the exchange rate depreciation and the fiscal stimulus “had significant impacts upon the level of activity” (see Nanto, D.K. and Takagi, S. (1985) ‘Korekiyo Takahashi and Japanese Recovery from the Great Depression’, American Economic Review, 75, 369-74).

Most of the studies suggest that the monetary policy easing (cutting interest rates) was not as significant as the other two stimulus measures.

Another strand of argument is that in the transition from democracy to fascism in the early 1930s, the trade unions were suppressed and industrial disputation fell. Real wages fell as a result, which some claim caused employment and output to rise.

An interesting paper was published on September 30, 2000 by the Korean scholar Myung Soo Cha – Did Korekiyo Takahashi Rescue Japan from the Great Depression?.

It sought to decompose these stimulus factors and wage reductions to see order their impact on the exceptional recovery during the Great Depression. He also includes world output impacts (on Japanese exports) to see whether the recovery was driven by events outside of Japan.

He uses statistical techniques (Vector Autoregression) and historical data released by the Bank of Japan to show that it was the fiscal initiative that “was critical in reversing the downswing” in Japan in the early years of the Great Depression.

As an aside, the Bank of Japan runs an excellent Historical Statistics page. There are other sources of data that is of use in studying this period – for example the League of Nations, International Statistical Yearbook – which is available on-line through Northwestern University in the US.

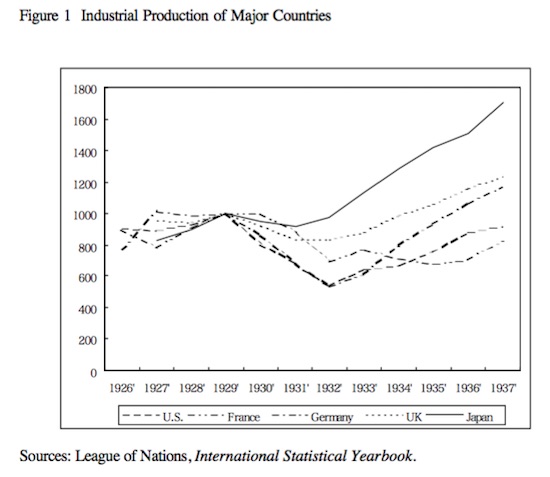

The next graph is a reproduction of Myung Soo Cha’s Figure 1 and show the evolution of Industrial Production from the mid-1920s to 1937.

It is clear that Japan’s experience was quite different to the other major economies of the day, especially after the major stimulus package introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo.

It is also interesting that the turning points in the graph for the respective countries “matches the sequence of going off gold in the wake of the Depression: Britain, Germany and Japan in 1931, the U.S. in 1933, and finally France in 1936”. That is not coincidental.

I won’t go into his methodology (it is standard) and you can read the paper yourself if you are interested in this sort of econometric analysis.

The results of his study are fairly clear:

1. He writes “one cannot but be impressed by the prominent role of Takahashi’s fiscal expansion in ending the Great Depression in Japan”.

2. “In particular, his deficit spending was found to have been crucial in ending the depression quickly”.

3. “Devaluation did help during 1932, but its contribution to output growth was modest.”

4. “The depreciating yen provided some stimuli as well, but they were not sufficiently strong to outweigh the contractionary influences from the rest of the world.”

Another finding from Shizume Mazato’s work is that while inflationary expectations rose somewhat during the shift from liberal democracy to fascism, “the shift in expectation from deflation to inflation was chiefly the result of the currency depreciation, not the BOJ underwriting of government bonds”.

Some might argue that it was the increased military spending that provided the fiscal stimulus, which would be undesirable in today’s world.

But research suggests that the military part of the fiscal shift to stimulus was fairly insignificant (see for example, Metzler, M. (2006) Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan, Berkeley, University of California Press).

Conclusion

There is little doubt that Takahashi Korekiyo’s economic policy stance – which was very MMT in operation – saved Japan from the Great Depression.

The large fiscal stimulus that was mostly underwritten with central bank credit did not cause interest rates to sky-rocket nor inflation to accelerate.

Inflation rose for a time then fell again but this was mainly the result of the massive exchange rate depreciation. That is a result that would always occur in a small open-economy such as Japan (at the time – small that is).

While there were aspects that were unnecessary – for example, the military spending – it is clear that Takahashi Korekiyo’s ‘experiment’ has relevance for us today in discussions concerning Overt Monetary Financing.

I have argued in my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – that OMF could save the Eurozone (from itself).

But try to get the policy makers in Brussels and Frankfurt to display as much policy acumen and foresight as Takahashi Korekiyo did in 1931.

Politics in the Pub – Hamilton – November 17, 2015

Tonight, I will be the speaker at the Politics in the Pub, which is held at the Hamilton Station Hotel, Beaumont Street, Hamilton (a suburb of Newcastle, NSW).

The title of my talk will be ‘Why budget deficits are good for Australia’ and I will motivate the talk with the quote from US philospher Daniel Dennett who told the New York Times on April 29, 2013 that:

There’s simply no polite way to tell people they’ve dedicated their lives to an illusion …

We will have some fun with that!

The event starts at 18:30.

I hope to see local readers there.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

All due credit to the Korekiyo policies. Now we all know that the resulting apparent economic strength was directed into imperial ambitions.

I say apparent because the Japanese were in a very fragile position prior to their attack on Pearl Harbour.

They were opportunists and gamblers and they lost – big time. Here in Australia we can be thankful that they were such fools and that we had a strong ally who had an interest in defending us.

Don’t count on a repetition of those happy circumstances.

All of the delusive thinking and consciously bought regressive monopolistic forces come out at times like the 30’s and like now. They were wrong then, they are wrong now. OMF is enlightened….as far as it goes. It’s only real problem is it only goes from private finance….to public finance. It needs to be extended all the way to the individual. That doesn’t mean the government can’t additionally fund infrastructure etc. Of course it can, and of course it should…with reasonably prudent overseeing so that we don’t end up building thousands of “bridges to no where” and also don’t end up with 5 powers with armies and navies the size of the US.

I know you desire not to have a discussion of Social Credit here Bill, but the relevance of facts like C. H. Douglas’s speaking tour of Japan in 1929 which was enthusiastically received if fascistically twisted by the imperialistic/militaristic forces there….cannot be ignored.

You are correct to point out that hyper-inflation is not a credible critique as it requires a compliant central bank to lend to speculators so that they can short the currency and destroy it as was the case in Weimar. And you are also correct in saying that inflation was not a significant factor in Japan as well, but that was mostly because the war was on and war is always “good business.” Inflation however would have and will occur because….who and what is to stop businesses from raising their prices as they see demand rising? The situation cries out for a macro-economic policy like a rebated back to participating merchants retail discount to the consumer. If you don’t do that the regressive and monopolistic financial powers and their austerian lackeys will (correctly) carp on and on about 3-5% inflation until OMF is politically reversed. Put sufficient dividend and macro discount mechanisms in there and drive a stake through the heart of the 5000 year old problematic business model of finance…once and for all.

Amazingly topical as ever 🙂

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/16/japan-enters-fifth-recession-in-seven-years-in-latest-blow-for-abenomics

Steve, effectively what you want is a merger of microeconomics and macroeconomics. However desirable that goal is, it is impossible at the present stage of development of the discipline. It is an unreasonable expectation. Analogously, there is a need to integrate quantum theory with general relativity, but physics is nowhere near achieving that, so far elusive, goal, and physics has been developed to a greater degree than economics.

Nice blog on this from a few years ago… Some references in there too that might be of interest.

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2011/08/takahashi-korekiyo-and-fiscal-stimulus.html

Korekiyo’s policy certainly helps. But I think Japan’s occupation of China’s Manchuria helps a lot more too. For very little costs, Japan obtained hugh amount of real wealth: labor, material and market.

Larry,

I want to integrate micro and macro not merge them. There’s an important difference. The latter doesn’t invalidate any of the former’s realities and vice versa although the result IS a third and unified whole. That the discipline is undeveloped goes without saying. Where it is undeveloped is philosophically because it is based on power, profit and control instead of freedom and flow/free flowingness. Once economists realize the necessity of making the paradigm shift from the former to the latter policy will simply be a straighforward and doable task of logic. Does this mean everyone and every agent will magically be economically redeemed…of course not, but with policy actually being in everyone’s economic and personal interest…most will comply and see that freedom and profit are not mutually exclusive. That is how paradigms become paradigms.

As for an integration of quantum. theory and relativity are concerned I would suggest it’s basically already been done…it’s just that the paradigm of mechanical science ONLY…stands in the road of its realization.

Steve,

“Inflation however would have and will occur because….who and what is to stop businesses from raising their prices as they see demand rising?”

If there is an output gap in the economy, then output rises rather than prices. Anyone who raises prices instead would lose market share.

Kind Regards

Larry,

I want to integrate micro and macro not merge them. There’s an important difference. The latter doesn’t invalidate any of the former’s realities and vice versa although the result IS a third and unified whole. That the discipline is undeveloped goes without saying. Where it is undeveloped is philosophically because it is based on power, profit and control instead of freedom and flow/free flowingness. Once economists realize the necessity of making the paradigm shift from the former to the latter policy will simply be a straighforward and doable task of logic. Does this mean everyone and every agent will magically be economically redeemed…of course not, but with policy actually being in everyone’s economic and personal interest…most will comply and see that freedom and profit are not mutually exclusive. That is how paradigms become paradigms.

As for an integration of quantum. theory and relativity are concerned I would suggest it’s basically already been done…it’s just that the paradigm of mechanical science ONLY…stands in the road of its realization.

CharlesJ,

Yes, they will risk that, but the herding instinct in profit making systems is pretty strong, and as they say “a little dab will do ya”.

A very informative post. I think I had previously heard Takahashi Korekiyo referred to as a sort of “Keynes-before-Keynes” (or maybe more accurately a “Lerner-before-Lerner”) but I had no idea quite how substantial his policy impact was, or how innovative his fiscal measures were.

I would also be interested to hear Prof Mitchell’s comments regarding the apparent return of Japan to recession. I’ve heard it suggested that a prior decision to increase the Japanese sales tax may explain subsequent poor growth performance. Based on my (admittedly very limited) understanding of MMT, would I be correct in thinking that the problem lies in the Japanese central government’s fiscal deficit having been too small (with the sales tax decision one manifestation of this) over recent quarters, given the Japanese balance of trade + the savings desire of the Japanese domestic private sector?

As an aside, does Prof Mitchell know if there is any interest in MMT in Japan among academics/officials/civil society? Have you, Prof Wray, Prof Kelton etc ever been invited to speak at a conference in Japan to discuss ways of ending Japanese economic stagnation? I’m always interested in the geographical distribution of awareness about MMT. One of the issues we have here in the UK is that, even if one wanted to encourage an exploration of things like functional finance within, say, the UK Labour Party, is that (as far as I know) there aren’t any UK-based academics with an MMT perspective, so exposure of UK progressives and left-wingers to MMT is limited to internet contact and sporadic (very helpful but limited in number) visits from overseas, like the one Prof Mitchell spoke at in London earlier this year.

Also, Prof Mitchell, could I ask you if your politics in the Pub speech up on-line via your youtube account at some point? The talk sounds informative, and I’m always interested to see the responses of (presumably progressive) laypersons to MMT when their exposed for the first time! It’s intriguing to see the audience’s usual transformation from a wary “surely it’s too good to be true” to a justifiably angry “I can’t believe we’ve wasted so many lives through unecessary unemployment” by the end of a presentation on MMT.

Dear Steve and Larry (at various times)

It is not possible to integrate micro and macroeconomics because you then fall foul or ignore the fallacy of composition in reasoning from specific to general and the aggregation problem.

Mainstream macroeconomics as taught in many textbooks really tried to overcome the latter by creating the representative agent. It doesn’t work.

I also do not see the point.

best wishes

bill

“As for an integration of quantum. theory and relativity are concerned I would suggest it’s basically already been done…it’s just that the paradigm of mechanical science ONLY…stands in the road of its realization.”

Big difference between integrating Special Relativity with Quantum theory [ Paul Dirac et al] and integrating General Relativity with Quantum Theory [Pretty much hopeless pursuit which has led to M-Theory and String Theory… and so on].

The only relevance between Quantum theory and economics is that economists have hijacked some of the maths in an attempt to validate their scientism – it’s not fooling me though.

How did it go at the Pub Bill? …. Was there a melee? Did any Andrew Bolt fans have a go?

Maybe you are all too refined for that sort of thing in Newcastle.

Bill,

Yes, maybe I should restate what I actually think and believe. I believe economists are missing data that would clarify the two major problems afflicting modern technologically advanced economies, namely chronic scarcity of individual incomes and inflation that lead to those economy’s instability. They are missing it because they are simply not looking in the correct place where that data can be garnered and calculus applied to it in order to see its dynamic systemic destabilizing effects. Deciphering this would make clear the policies necessary to stabilize the system. All of the current cutting edge research and theories align with and are converging on the philosophy and policies of the new theory and paradigm that I hope economic theory is awakening to. For instance General Disequilibrium/Flux/Process (Steve Keen) instead of General Equilibrium, monetary addition/abundance (MMT) instead of monetary scarcity/austerity/subtraction, both structural and central (Public Banking) instead of the hiding in plain sight 800 pound monopolistic gorilla of Private Finance and finally integrating individual and systemic monetary grace/Gifting into profit making systems instead of always being “behind the curve” of the increasingly disruptive effects on aggregate individual incomes due to the logics of efficiency that drive and dictate profit making systems, technological innovation and AI.

Alan,

“The only relevance between Quantum theory and economics is that economists have hijacked some of the maths in an attempt to validate their scientism – it’s not fooling me though.”

Yes, I completely agree with this. Scientism is really just the flip side of religiosity. I recommend a paraphrase of the well known zen koan: What is the sound of scientism and religiosity clapping?

Bill,

I was thinking of the possibility of integrating the two sometime in the future without falling foul of the fallacy of composition, although I did not mention that. I agree that the concept of the representative agent doesn’t work and that trying to integrate what are two distinct disciplines at this point in time and the near future would be pointless. And, as far as we know at this moment in time, it may be, as you intimate, forever pointless.

Steve,

The possible solution to integrating what are presently two subdiscipliines of a single field doesn’t lie in the nature of the data, it lies at the theoretical level. It isn’t a matter of new, better, different data; the bar to your image of integration lies in the fact that the two paradigms are deeply incompatible with one another, and data can’t fix this.

It is perhaps not irrelevant to note that some of those who presently are interested in the integration of microeconomics and macroeconomics see it as a program of “reducing” macro theory to micro theory. This is not what I meant. The only completely successful scientific theoretical integration has been the reduction of the theory of heat to the theory of molecular kinematics, thus rendering the theory of heat scientifically redundant, though not thereby phenomenologically redundant. All other attempts at such reductions have failed. I think we have to view this as a failed research program (I am ignoring the claimed reduction of chemistry to physics here.).

If it ever proved possible to integrate macro econ and micro econ, it would not consist of reducing one theoretical enterprise to the other. Each would have to be seen as playing an equal part. The likelihood of carrying out such a program either now or in the near future? Nil.

Larry,

“The possible solution to integrating what are presently two subdiscipliines of a single field doesn’t lie in the nature of the data, it lies at the theoretical level. It isn’t a matter of new, better, different data; the bar to your image of integration lies in the fact that the two paradigms are deeply incompatible with one another, and data can’t fix this.”

I disagree. I think it is both data and theory. If data is not being perceived its missed. If it is looked at and then fit into a mistaken ideology as DSGE I believe interprets the data I refer to, its actual reality is misperceived/twisted. For instance the data on costs and incomes is misinterpreted within General Equilibrium. What the data actually tells us is that the system is in a continual/dynamic state of Disequilibrium. This implies adult, responsible action/policy to stabilize/equilibrate the system instead of treating the system/market as an unquestionable God. Paradigms are general ideas/philosophies. The current paradigms in economics are Debt and Stasis. The new paradigms need to be Grace as in Gifting and Process as in Dynamic Flow. It is no coincidence that the philosophical underpinnings of each of the cutting edge theoretics of MMT, Disequilibrium theory, Positive Money, Public Banking and Social Credit express aspects of the the natural concept of Grace and Flow. Having said all of this I wouldn’t disagree that the philosophical/theoretical conclusions are more important than merely then data, but that is because the integrative mindset….is thoroughly integrative and not mere in any sense…and the result of the integration of the data within a more realistic philosophical/theoretical interpretation is a third more unitary understanding of the whole of the discipline.